Abstract

Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer deaths in this country. Conventional therapeutic treatments including surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, have achieved only limited success. The overexpression of proteases such as urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), its receptor (uPAR) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), is correlated with the progression of lung cancer. In the present study, we used a replication-deficient adenovirus capable of expressing antisense uPAR and antisense MMP-9 transcripts to simultaneously downregulate uPAR and MMP-9 in H1299 cells. Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection of H1299 cells resulted in a dose-and time-dependent decrease of uPAR protein levels and MMP-9 activity as determined by western blotting and gelatin zymography respectively. Corresponding immunohistochemical analysis also demonstrated that Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection inhibited uPAR and MMP-9 expression. As shown by Boyden chamber assay, Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection significantly decreased the invasive capacity of H1299 cells compared to mock and Ad-CMV (empty vector)-infected cells in vitro. Furthermore, Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection inhibited capillary-like structure formation in H1299 cells co-cultured with endothelial cells in a dose-dependent manner compared with mock- and Ad-CMV-infected cells. Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 injection caused the regression of subcutaneously induced tumors after subcutaneous injection with H1299 lung cancer cells and inhibited lung metastasis in the metastatic model with A549 cells. These data suggest that Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 demonstrates its antitumor activity against both established and early phases of lung cancer metastases by causing the destruction of the tumor vasculature. In summary, adenovirus-mediated inhibition of uPA-uPAR interaction and MMP-9 on the cell surface may be a promising anti-invasion and anti-metastasis strategy for cancer gene therapy.

Keywords: lung, invasion, MMP-9, uPAR, antisense, angiogenesis

Abbreviations: uPA (urokinase-type plasminogen activator), uPAR (uPA receptor), CMV (cytomegalovirus), SV40 (simian virus type 40), PBS (phosphate-buffered saline), MMP-9 (matrix metalloprotease-9); metastasis

Introduction

Non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLC) have a rather unpredictable prognosis and account for approximately 80% of primary lung cancer (1). A crucial step during invasion and metastasis is the destruction of biological barriers such as the basement membrane, which requires activation of proteolytic enzymes (2). Proteases contribute to each step beginning with the first breakdown of the basal membrane of a primary tumor to the extended growth of established metastases. Many studies have shown that enhanced production of members of the plasminogen activator pathway and matrix metalloproteinase family contributes to tumor invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis (3). The uPA receptor focuses uPA activity on the cell membrane, thus regulating cell-surface associated proteolysis by uPA, which converts the zymogen plasminogen to plasmin (4). Plasmin is a broad-spectrum protease, which promotes extracellular-matrix (ECM) degradation by directly degrading ECM components and activating latent collagenases and metalloproteases (5). The uPA receptor is also involved in the regulation of cell adhesion and migration independent of the enzymatic activity of its ligand (6). It is capable of transmitting uPA-mediated extracellular signals inside the cell, probably through the association with different types of integrins (7) and with vitronectin (VN) (8), an ECM component (9). Predominant stromal expression of uPA correlated with tumor size and lymph node metastasis in a large series of lung tumors (10,11). PAI-1 and uPA are strongly correlated and linked to tumor progression parameters in lung cancer, suggesting a synergistic effect on tumor cell migration (12). Consequently, inhibition of uPA-uPAR interaction on the cell surface might be a promising anti-invasion and anti-metastasis strategy. It has been demonstrated that inhibition of uPA catalytic activity and its binding to the receptor by various strategies, such as neutralizing antibodies, competitive peptides, recombinant molecules, and antisense oligonucleotides, can inhibit tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo (13).

Another important family of proteinases responsible for the ECM destruction involved in cancer progression is the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family. Among the many MMPs that have been identified, MMP-2 (Gelatinase-A) and MMP-9 (Gelatinase-B) are thought to be key enzymes because they degrade type IV collagen, the main component of ECM (14). Increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was shown to correlate with an invasive phenotype of cancer cells (15). Several recent reports confirmed lung neoplastic cells produce both matrix metalloproteases and their inhibitors (16–18). MMP-9 is a Mr 92,000 gelatinase that degrades type IV collagen and was found to be significantly associated with survival in lung cancer patients (19–21). The prognostic impact of homogeneous MMP-9 expression was shown to be independent from possible prognostic joint effects of pT-status, pN-status, tumor histology and tumor grading, thus suggesting MMP-9 as an interesting target for adjuvant anticancer therapy in operable NSCLC using specific inhibitors of MMP-9 (22).

Many potential genes and gene therapy strategies that have been tested in vitro and in vivo have demonstrated tumor suppression. We previously demonstrated efficient reduction of metastasis with ex vivo treatment of lung cancer cells with adenovirus encoding antisense transcript for uPAR (23). Here, we demonstrate the therapeutic potential of adenovirus expressing antisense transcripts against two genes; a proteases receptor, urokinase plasminogen activator receptor and (uPAR) and a matrix metalloprotease (MMP-9) in lung cancer. We demonstrate that an adenovirus bicistronic construct carrying antisense message for uPAR and MMP-9 (Ad-uPAR-MMP-9) significantly decreased in vitro invasion through Matrigel-coated membranes and prestablished tumor growth and lung metastasis in vivo after subcutaneous injection of H1299 lung cancer cells and in a metastatic model using A549 lung cancer cells.

Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

A549 and H1299 cells were obtained from the American Type culture collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured in 100 mm tissue culture plates in RPMI 1640 (ATCC Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Japan), 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Inc., Frederick, MD), hereafter referred to as complete medium. Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs) were obtained from Cambrex Bio Science Rockland, Inc (CC-2616) and maintained in large vessel endothelial medium supplemented with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)/heparin, epidermal growth factor and cortisol in the presence of amphoteracin/gentomycin. Virus constructs were diluted in serum-free culture media to the desired concentration and added to cell monolayers or spheroids and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The necessary amount of complete medium was then added and cells were incubated for the desired time periods.

Adenoviral production

Construction of adenoviral vector expressing antisense sequences for human uPAR and MMP-9 was performed as previously described (24). The adenovirus contains a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter followed by a truncated 300 bp antisense message complementary to the 5′ end of the uPAR gene, a 520 bp antisense message complementary to the 5′ end of the MMP-9 gene and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal. Following previously established methods, suspensions of recombinant adenovirus were prepared by amplification in 293 cells followed by purification using three consecutive CsCl gradients (25). Viral titers were estimated using optical density at 260 nm and standard plaque assay.

Gelatin zymography

MMP-9 expression in conditioned media of lung cancer cells infected with mock, Ad-EV (100 MOI), or the indicated doses of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9, was analyzed by gelatin zymography as previously described (24). Briefly, the conditioned media were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in the presence of 1 mg/ml gelatin. The resulting gel was washed in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 2.5% Triton X-100, and was then incubated for 16 h in a reaction buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10−6 M ZnCl2) at 37 °C. After staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250, gelatinases were identifiable as clear bands.

Western blot

Lung cancer cells were infected with mock, the indicated doses of Ad-EV (100 MOI), Ad-uPAR, or Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Four days after infection, the medium was replaced with serum-free medium and the cells were further incubated for an additional 15–16 h. At the end of incubation, the conditioned medium was collected and cells were harvested and cellular proteins were extracted with lysis buffer [40 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 150 mM NaCl] containing Complete Mini, a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Total proteins from the medium for MMP-9 and cell lysates (for uPAR) were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). After blocking with 5% non-fat, dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline, membranes were incubated with the mouse monoclonal uPAR or MMP-9 (Biomeda, Foster City, CA) or the mouse monoclonal anti-actin (Biomeda) antibody. The membranes were then developed with peroxidase-labeled antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) and chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Actin protein levels were used as a control for equal protein loading.

Invasion assays

The ability of lung cancer cells to migrate through Matrigel-coated filters was measured using Transwell chambers (Costar, Cambridge, MA) with 12.0-μm-pore polycarbonate filters coated with 30 μg of Matrigel in the upper side of the filter (Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA). H1299 were infected with mock, empty vector (Ad-EV), Ad-uPAR (100 MOI), or Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 (50 MOI). After 5 days the cells were trypsinized and resuspended in serum-free medium were seeded on the upper compartment of the chamber and incubated for 24 h. At the end of incubation, the cells were stained and the cells and matrigel on the upper surface of the filter were carefully removed with a cotton swab. The invasive cells adhering to the lower surface of the filter were quantified under a light microscope (20X). The data are presented as the average number of cells attached to the lower surface from randomly chosen fields. Each treatment condition was assayed using triplicate filters and filters were counted at five areas.

Migration assay

Spheroids were initiated by inoculating 1 × 105 exponentially growing H1299 cells onto 96-well low attachment plates (Corning Costar No.: 3471) with 200 μl of culture medium and incubated in a shaker at 200 rpm at 37 °C for 72 h. A single spheroid formed in each well. The medium was replaced and spheroids were cultured for another 5 days. Single spheroids were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in trypsin solution, and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. After the addition of complete medium, cell suspensions were passed twice through an 18-gauge needle to disrupt cell clumps and the mean cell number per spheroid was determined. The spheroids were infected with mock, Ad-EV (100 MOI), or the indicated concentrations of Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 for 48 h. The spheroids were then removed from low attachment plates, a single spheroid was placed in each well of an eight-well chamber slides, and slides were incubated for an additional 72 h. Then, the spheroids were stained using a HEMA 3 stain kit and photographed using a light microscope.

Co-culture assay

H1299 lung cancer cells were plated in 8-well chamber slides (5 × 103) and infected with mock, Ad-EV (100 MOI), and various doses of Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 for 4 days. The culture medium was replaced and human endothelial cells (2 × 104) were plated and co-cultured for 72 h. After incubation, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin for 1 h and endothelial cells were probed with antibody for factor VIII antigen (Factor VIII antibody, DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA). The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. The cells were then washed and examined under a laser scanning confocal microscope. Photomicrographs were subjected to a customized routine-based image analysis tool.

Animal experiments

Congenitally athymic female nude mice [BALB/c, nu/nu (Harlan)] were purchased germ-free at 2 to 3 weeks of age and maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment throughout the experiment. Animals were kept in sterile cages (maximum of five mice/cage) bedded with sterilized soft wood granulate and fed irradiated rat chow ad libitum with autoclaved water at a 12 h light/dark cycle. Animals were kept at least 1 week before experimental manipulation. All manipulations were performed in a laminar flow hood. Before tumor inoculation and radiographic examination, mice were anesthetized with an i.p. mixture of 50 mg/kg ketamine and 10mg/kg xylazine. For euthanasia, animals were given a lethal dose of ketamine and xylazine.

Subcutaneous tumors

A suspension of H1299 cells (2.5 × 106 cells in 0.1 ml RPMI 1640 medium) was subcutaneously injected into the left side of at least five nude mice per condition. Tumors were allowed to grow to approximately 5–6 mm and the mice were separated into three groups. Each group received Ad-EV (5 × 109) or 5 × 108 PFU or 5 × 109 PFU of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 injections around the tumor on days 10, 15 & 20. We monitored the effect of tumor formation on the mice by looking for behavioral changes, such as inactivity and lameness, and by observing possible weight loss. All of the animals remained healthy and active during the course of the experiment. Tumor sizes were measured every 5 days and mice were sacrificed at day 60. Tumor volumes were determined according to the formula V=0.4 × A × B2 where ‘A’ denotes the largest dimension of the tumor and ‘B’ represents the smallest dimension.

Metastasis model

A549 (2 × 106 in 100 μl of serum-free medium) were injected into the left flank of 15 mice. The mice were separated into three groups composed of 5 animals each. After 3 weeks, when the tumors had reached 8–10 mm in size, the mice received intravenous injections of PBS or 5 × 108 PFU of either Ad-EV or Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 three times at 5-day intervals. The mice were sacrificed after 12 weeks. The subcutaneous tumors and the lungs were immediately dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C for 24 h. The lungs were embedded in paraffin and evaluated using H & E staining. The sections were screened and evaluated by a pathologist blinded to treatment condition.

Results

The Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection efficiently downregulates uPAR and MMP-9 protein levels in lung cancer cells

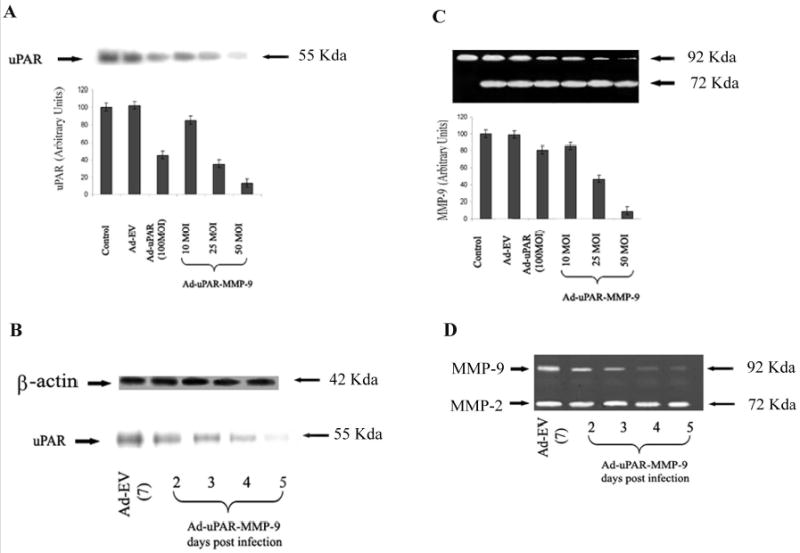

We examined two lung cancer cell lines (H1299 and A549) for uPAR and MMP-9 expression. uPAR protein levels and MMP-9 activity was assessed using western blotting and gelatin zymography respectively. Cells were infected with mock, empty vector (Ad-EV), Ad-uPAR (100 MOI) or various doses of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Immunoblotting indicated that Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection inhibited uPAR expression and in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Densitometric quantitation of uPAR protein bands indicated a 20% decrease in uPAR expression in cells infected with 10 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. This decrease was nearly 90% in cells infected with 50 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 as compared with mock and Ad-EV-infected controls. Cells infected with the adenovirus expressing antisense message to only uPAR (Ad-uPAR at 100 MOI) decreased uPAR expression by approximately 40% as compared to the controls (Fig. 1A). Kinetics of uPAR expression within cells infected with 50 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 indicated that protein levels decreased significantly by day 4 and were inhibited by more than 90% by day 5 (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 decreased uPAR and MMP-9 expression in lung cancer cells.

(A) Western blot analysis of uPAR protein expression in cell lysates from H1299 infected with mock, Ad-EV (100 MOI), or the indicated doses of Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. (C) Conditioned medium was collected from the H1299 cells, 60 μg of protein from these samples were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer and run on 10% SDS-PAGE gels containing 0.1% gelatin (gelatin zymography). Densitometric quantitation of uPAR and MMP-9 was performed and the data represent average values from 3 separate experiments. uPAR (B) & MMP-9 (D) expression in H1299 cells infected with 50 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 at the indicated time points.

Similarly, Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection inhibited the levels of MMP-9 activity in a time-and dose-dependent manner as determined by gelatin zymography. Densitometric scanning of the bands indicated that MMP-9 was inhibited by 15% in cells infected at 10 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 and 54% in cells infected at 25 MOI. This decrease reached 92% in cells infected with 50 MOI of the virus when compared to mock and Ad-EV controls. Ad-uPAR had a very minimal effect on MMP-9 expression (Fig. 1C). Progression of MMP-9 inhibition in cells infected with 50 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 indicated a significant decrease by day 3 and reached approximately 90% by day 5 as compared to mock and Ad-EV-infected H1299 cells (Fig. 1D). A similar pattern of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 effect was also observed in A549 lung cancer cells (data not shown).

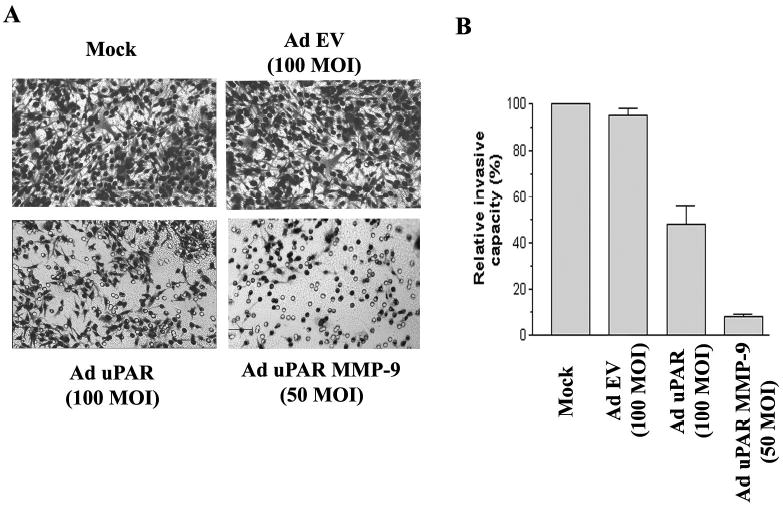

Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection could remarkably inhibit the invasive capacity of lung cancer cell lines in vitro

The invasive potential of the lung cancer cells after infection with Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 was determined using the matrigel invasion assay. Fig. 2A demonstrates decreased staining of the invaded cells through the Matrigel with Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection compared to the mock and empty vector (Ad-EV) controls. Quantitative analysis indicated that Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 was more effective in decreasing the invasiveness of these cells compared to Ad-uPAR. Tumor cell invasion decreased nearly 50% in cells infected with 100 MOI of Ad-uPAR and more than 90% in cells infected with 50 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibits lung cancer cell invasiveness through Matrigel.

H1299 cells were trypsinized and counted 3 days after infection with mock, Ad-EV (empty vector), or the indicated doses of Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Invasion assays were carried out in a 12-well transwell units (1 × 106 cells/treatment condition in triplicate). After a 24 h incubation period, the cells that had passed through the filter into the lower wells were fixed and photographed (A). The percentage of invasion was quantitated as described in materials and methods (B). Values are mean ± S.D. from 5 different experiments.

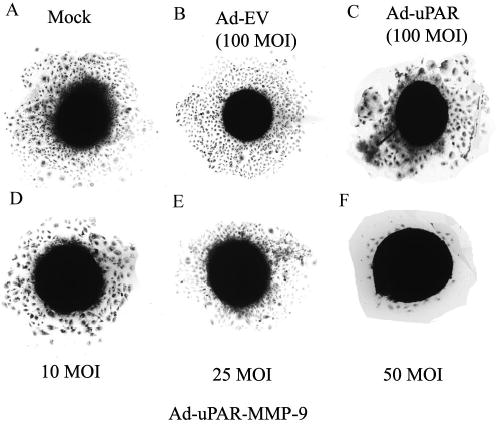

Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibits spheroid migration

The cleavage of ECM components is a key requirement for cell migration; proteolysis allows release of growth factors and other signaling molecules from extracellular matrix, which in turn, aid in migration (26). Multicellular spheroids composed of transformed cells are known to mimic tumor growth characteristics. H1299 cells were allowed to form spheroids and were infected with mock, Ad-EV, Ad-uPAR, or Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Outgrowth and cell density were the parameters chosen to evaluate migrational capacity. There was extensive outgrowth of cells in spheroids infected with mock and Ad-EV (Fig 3A and B). Spheroids infected with 100 MOI of Ad-uPAR (3C) showed less migration of the cells from the center. However this inhibition in the outgrowth of cell from the spheroids was more distinct with Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 and was in dose dependent manner (Fig 3 D,E,F)

Figure 3. Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibits cell migration from lung cancer cell spheroids.

H1299 spheroids were infected with mock, Ad-EV, or the indicated doses of Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. After 3 days, single spheroids were placed in the center of wells in 8-well chamber slides and cultured at 37 °C for 48 h. At the end of the migration assay, spheroids were fixed, stained and photographed.

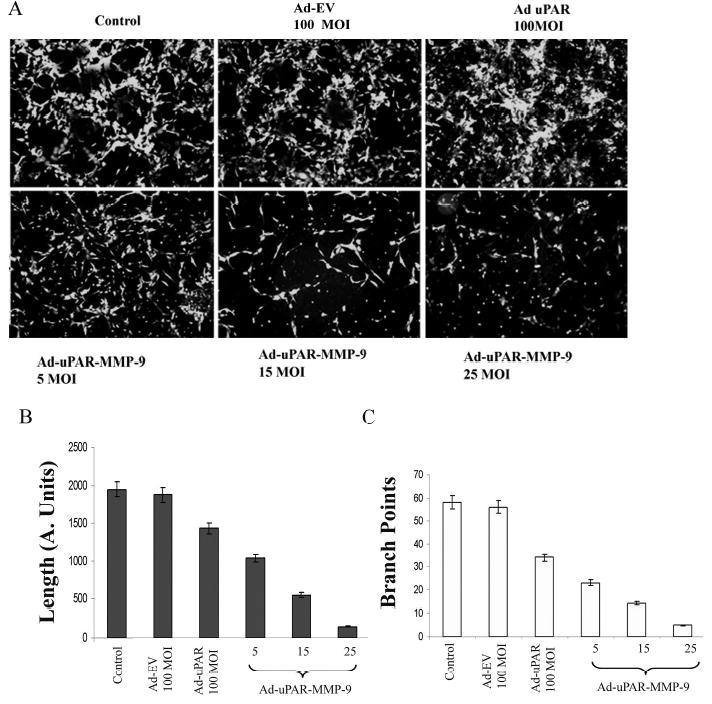

Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibits tumor cell induced angiogenesis

Since tumor growth and proliferation depend on neovascularization, we evaluated the anti-angiogenic potential of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 in vitro using human microvascular endothelial cells. In this system, endothelial cells migrate to form tubular structures in the presence of tumor cells. Human microvascular endothelial cells were cultured in the presence of lung cancer cells and infected with various doses of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. A very distinct capillary network was visualized following Factor VIII staining of endothelial cells cultured in the presence of mock and Ad-EV-infected lung cancer cells. In contrast, Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 infection of the lung cancer cells inhibited the cancer cell-induced capillary network formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Image analysis indicated that Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 treatment decreased the number of branch points as well as the length of vascular tubules in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B & C). Lung cells infected with 100 MOI of Ad-uPAR caused a 25% decrease in the length and a 50% inhibition in the number of branch points. However, Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 had a more dramatic inhibition in the tumor-induced angiogenesis. 5 MOI of this virus inhibited the length of the capillaries by approximately 50% and the number of branch points was reduced to 24 compared with 59 in mock and 56 in the Ad-EV-infected cells. This decrease was more pronounced with increasing MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9.

Figure 4. Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibits lung tumor cell-induced angiogenesis.

H1299 cells were infected with mock, Ad-EV, or the indicated doses of Ad-uPAR and Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Four days after infection, conditioned media from these cells was used to culture human endothelial cells for 72 h. The cells were then washed, stained and photographed (A). Image pro analysis of the same showing the length (B) and the branch points (C).

Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibits tumor growth in vivo and significantly reduces the metastatic capacity of lung cancer cells in vivo

Subcutaneous tumor model

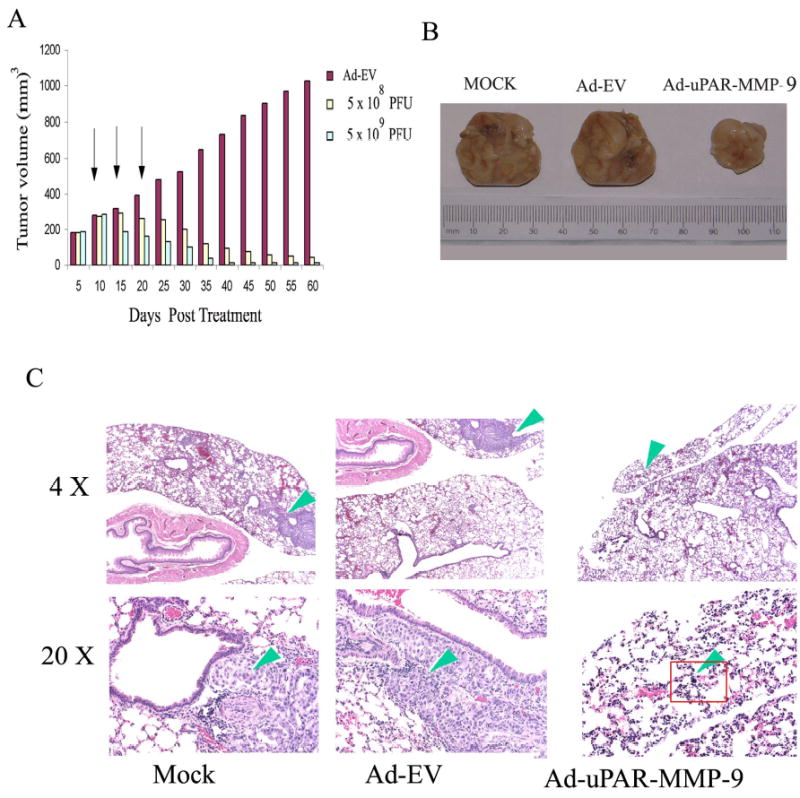

H1299 cells formed rapidly growing primary tumors. We compared the tumor inhibitory effect of two different concentrations of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Three sets of mice with five animals/group received three doses of either 5 × 109 PFU of Ad-EV or 5 × 108 or 5 × 109 PFU of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 intratumorally. All the tumors receiving Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 showed regression starting on the 9th day after injection. Analysis of tumor size revealed that tumors injected with 5 × 108 PFU of virus displayed a more sluggish response with respect to tumor regression than compared to those mice, which received 5 × 109 PFU of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 virus. However, both concentrations of the virus regressed tumor growth nearly 90% in all the mice by the end of the experiment (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Inhibiton of subcutaneous tumor growth.

(A) Nude mice were injected with H1299 cells (5 × 106 /100 μl). When the tumor reached 5–6 mm in size, mice were injected tumorally with Ad-EV (5 × 109) or Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 (5 × 108 or 5 × 109) 3 times. Tumor size was measured using calipers as described in methods. Inhibition of subcutaneous tumor growth and lung metastasis. A549 cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. After 2 weeks, the mice received intravenous injections of PBS or 5 × 108 PFU of either Ad-EV or Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 three times at 5-day intervals. Representative subcutaneous tumors are shown for each treatment condition (B). H & E staining of lung sections from the same mice (C).

Lung metastasis model

A549 cells formed lung metastases in the mice that received subcutaneous inoculation. We examined the in vivo effect of three intravenous injections of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 given on the 10th, 15th and 20th day after the tumor inoculations on metastasis of lung tumors formed by the injection of A549 cells. Twelve weeks after subcutaneous inoculation of tumor cells, at which point the primary tumor had reached its maximum volume, the animals were sacrificed. There was a significant difference in the weight of the tumor volumes in the control mice when compared to the tumors from the mice that received Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 injections. The average tumor volume of the mice that received Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 was only 25% than the average tumor volumes of the mice that received PBS and Ad-EV (Fig. 5B). We performed a histologic analysis of metastatic foci among the lungs from the control mice and those that received Ad-uPAR-MMP-9. Analysis of the metastases in serial lung sections was performed under light microscopy. Lung metastases were observed in the control and Ad-EV-treated mice. The cancer cells varied in size and shape (polygonal, circular, or irregular). The nuclei also differed in size, displayed notable atypia and pathologic mitosis, and stained variably. However, no lung metastases were observed until the end of the experiments in mice treated with Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 with the exception of a single cell in one mouse (Fig. 5C). The results demonstrate the remarkable inhibition of metastatic nodules in the lungs of animals treated with Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 suggesting that uPAR and MMP-9 influence the metastatic capacity of lung cancer cells in vivo.

Discussion

The ability of neoplastic cells to migrate, invade and metastasize to other organs presents a major hurdle to successful therapeutic intervention. The degradation of basement membranes by tumor cells involves secretion and activation of proteinases, including the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and those involved in the plasminogen activation system. Moreover, recent evidence has shown multiple functions for MMPs, rather than simply degrading ECM, which include the mobilization of growth factors and processing of surface molecules. Anti-proteolytic approaches are valuable alternatives to conventional therapies. Using plasmin deficient mice, Bugge et al (27) demonstrated that all the steps involved in the growth and dissemination of a malignant tumor could take place in the complete absence of plasmin-mediated proteolysis. Similarly systemic administration of a synthetic gelatinase inhibitor demonstrated very similar effects on the dissemination of Lewis lung carcinoma as those of Plg deficiency, i.e., a moderate reduction in primary tumor growth and metastasis, and slightly increased survival (28). These studies led us to hypothesize whether the combined elimination of several cancer-associated matrix-degrading proteases could possibly have a synergistic or additive effect on impeding tumor dissemination. In recent years, much attention has been focused on anti-metastatic agents constructed by means of genetic engineering techniques for the therapy of malignant tumor cells. Here, we analyzed the efficiency of adenovirus-mediated synergistic expression of antisense sequences to uPAR and MMP-9 at inhibiting the invasive capacity, tumor growth and metastasis of lung cancer cells.

First, expression of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and matrix mettaloprotenase-9 (MMP-9) was characterized in H1299 and A549 lung cancer cell lines. The uPAR and MMP-9 bearing malignant lung tumor cells have greater access to the high concentrations of uPA and MMP-9, which facilitate matrix degradation and result in tumor cell invasion. Several components of the uPA system are potential targets for anti-invasive, anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic strategies (6,29). Increased expression of MMP-9 mRNA and MMP-9 protein have been found in many solid tumors (30), including NSCLC (16,19,31). Higher levels of MMP-9 mRNA have been found in stage III NSCLC compared to stages I and II (16). The expression of either MMP-9 or MMP-2 confers a worse prognosis in early stage adenocarcinoma of the lung (19). Infection with Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 decreased the expression of these two molecules by more than 90% in both lung cancer cells. It is interesting to note that only 50 MOI of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibited almost 90% of the uPAR protein expression as compared to Ad-uPAR infection, which carried the antisense message for uPAR alone and achieved this effect but at a much higher dose. Correspondingly, the modified Boyden chamber test in vitro showed that reduced invasiveness of these cells through a reconstituted basement membrane at a lower concentration of this bicistronic gene construct as compared to Ad-uPAR.

Next, migration of these cells was determined using a spheroid migration model. Multicellular spheroids composed of transformed cells are known to mimic the growth characteristics of tumors. It has been demonstrated that cells in spheroid culture (32) and even plateau-phase monolayer culture (33) respond differently to a variety of signals compared to the monolayer cultures. Inhibiton of uPAR and MMP-9 inhibited cell migration from tumor spheroids. Growth factors such as IGF I, IGF II, HGF, EGF and SCF induce migration of human, non-small cell, lung cancer cells in the presence of extracellular matrix (ECM) components (34). The ECM is considered a reservoir of growth factors, which are released by matrix protease-mediated ECM degradation (35). Growth factor activation could in turn be driven by the same matrix proteases (36). Growth factors were shown to promote invasiveness through their ability to enhance the expression and activity of matrix degrading MMP-2 and MMP-9 in non-small cell, lung cancer cells (37). Furthermore, activation of plasminogen-induced proteolysis is involved in the release and activation of numerous growth factors as well as transforming growth factor ß, which are all involved in invasion and angiogenesis. The capacity of lung cancer cells to invade was increased in vitro after treatment with CSF. In addition, this enhanced invasive behavior of the cancer cells stimulated by CSFs correlated with increases in MMPs and uPA activities (38).

Intratumoral and intravenous injection of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 inhibited subcutaneous tumor growth and lung metastases in mice implanted with lung cancer cells in animal models. The uPA/uPAR interaction has been shown to have an important role in tumor metastasis. A recombinant adenovirus encoding the non-catalytic ATF of mouse uPA prevents lung carcinoma metastasis (39) and protects mice in a liver metastasis model of human colon carcinoma (40). In our previous study, Ad-uPAR (adenovirus expressing an antisense message to uPAR) could partially inhibit lung metastasis when H1299 cells were treated ex vivo with this virus and injected intravenously (23). First, this may be because several factors in the uPA system, including uPAR binding capacity, the amount of uPA available for binding, endogenous uPA inhibitor PAI-1 as well as the ratio of potent active uPA and inactive ligands occupied on uPAR, are involved in determining the tumor’s ability to invade and metastasize. Second, this may also be because other proteases including metalloproteinases may compensate for a lack of uPA activity and uPAR protein. Other studies have demonstrated that cooperation between uPA/uPAR and metalloproteinases is required to complete the step for intravasation and consequently for metastasis (41). Upregulation of secreted MMP-9 also correlated with an increase in tumor growth kinetics and angiogenesis compared to cells expressing low MMP-9 levels (mock) or active MMP-9 on the tumor cell surface (MMP-9-LDL) in a breast cancer model. This enhancement was partially inhibited by doxycycline, indicating that these effects require the proteolytic activity of the secreted MMP-9 form (42). Several matrix metalloproteinase-inhibitors (MMPIs) are currently being investigated in clinical trials to assess their efficacy in maintenance of remission after other treatment modalities or in combination with standard chemotherapy (43). MMPIs that have been studied in NSCLC include batimastat (BB-94), marimastat (BB-2516), prinomastat (AG-3340) and BMS-275291 (44). Yamamoto (45) reported that ONO-4817, a third generation MMP inhibitor, inhibited progression of established lung micrometastasis by tumor cells expressing MMPs and that therapeutic efficacy was further augmented when combined with docetaxel. Liu (46) also suggest that the administration of prinomastat (AG3340) in combination with carboplatin may prolong survival in NSCLC patients. However, these inhibitors act against all MMPs. These sometimes lead to a negative response in the treatment of cancer since some MMPs could be expressed as a protective response, and therefore, play an important role in the host defense during tumorigenesis (47). In view of the role of MMP-9 in tumor progression and angiogenesis we constructed an adenovirus which expresses antisense message for uPAR and MMP-9 to determine if downregulation of two different proteases have an improved effect in inhibiting lung metastasis. In the present study, we could not detect any lung nodules in mice treated with Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 in the metastasis model. Histological examination revealed only one or two cells, which appeared to be neoplastic (blind reviewed by a pathologist). Therefore, our strategy to specifically down regulate two proteases simultaneously has achieved maximal tumor growth inhibition and has significant therapeutic potential.

To further characterize the relationship of uPAR and MMP-9 inhibition on tumor growth, we assessed the effect of Ad-uPAR-MMP-9 on tumor-induced angiogenesis in vitro. Tumor growth depends on the development of blood vasculature to bring in nutrients critical to sustain growth (48). The cell-associated plasminogen activator system is known to play a crucial role in the angiogenesis process by modulating the adhesive properties of endothelial cells in their interactions with ECM and in the degradation of ECM (49–52). Interference with the activities of the uPA system has been demonstrated to cause inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro in some cases (49, 53–55) and in vivo (39,54). ATF-based uPAR antagonists are known to have anti-angiogenic function mainly by blocking uPA/uPAR interaction (39,53). Recently, the recombinant kringle domain of urokinase (UK1) has been shown to present anti-angiogenic activity in vitro and in vivo (41). There is abundant evidence that MMPs, such as MT1-MMP, MMP-2, and MMP-9, are essential for angiogenesis (56,57). In addition to the breakdown of connective tissue and vascular migration, MMPs have also been thought to regulate endothelial cell attachment and proliferation (58). A strong correlation between microvessel density and tumor level of MMP-9 was demonstrated in pulmonary adenocarcinoma (59). Our results show that uPAR inhibiton in the cancer cells moderately inhibited the tumor-induced angiogenesis. In our study inhibiton of uPAR and MMP-9 expression had a more pronounced effect in inhibiting capillary formation in endothelial cells compared inhibiting uPAR alone. This result is supported by several studies which demonstrate that the cooperation between uPA/uPAR and MMP-9 is required for breaching of the vascular wall, a rate-limiting step for intravasation, and consequently for metastasis. Angiostatin, a plasmin derived angiogenesis inhibitor was shown to mediate the suppression of metastasis by Lewis lung carcinoma (60). However loss of angiostatin in plasmin deficient mice was not associated with an obvious increase in tumor neovascularization within primary tumors and metastases, as assessed by qualitative microscopic analysis using an endothelial cell marker, or on the growth rate of primary tumors or metastases (27). Kim and co-workers (41) have shown that mice treated with the MMP inhibitor marimastat reduced intravasation by more than 90% and also that uPA/uPAR and MMP-9 are required to break the vascular wall in order for tumors to metastasize.

Pericellular proteolysis appears more and more as a crucial event controlling the local environment surrounding normal and tumor cells. It is accomplished by a cooperative interaction between several proteases. Their functions have been extended from pericellular proteolysis and control of cell migration to cell signaling, control of cell proliferation and regulation of multiple stages of tumor progression including growth and angiogenesis. The degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) during tumor invasion and angiogenesis is likely to release active molecules stored in the matrix and/or to generate active fragments of matrix components which promote tumor growth, invasion and angiogenesis (61–63). A functional overlap between the PA and MMP systems was demonstrated in the dissection of the fibrin-rich provisional matrix by migrating keratinocytes (64). These findings demonstrated that the effective arrest of cancer progression would require the combined use of inhibitors of MMPs and inhibitors of the plasmin/plg activation system. Given the multiple roles of uPAR and MMP-9 in multiple biological events, the reduction in tumor growth and inhibiton of lung metastasis in Ad-uPAR-MMP-9-treated mice in our study has significant therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shellee Abraham for preparing the manuscript, Sushma Jasti and Diana Meister for manuscript review, and Noorjehan Ali for her help with the animal experiments.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Cancer Institute Grants CA75557, CA92393, CA95058, and N.I.N.D.S. NS47699 (to J.S.R.).

References

- 1.Shottenfeld D. Epidemiology of lung cancer. In: Pass HI, Mitchell JB, Johnson DH, Turrisi AT, Minna JD, editors. Lung Cancer. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & WIlkins; 2003. p.367–88.

- 2.Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Tumor invasion and metastasis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5054s–5059s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKay AR, Corbitt RH, Hartzler JL, Thorgeirsson UP. Basement membrane type IV collagen degradation: evidence for the involvement of a proteolytic cascade independent of metalloproteinases. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5997–6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dano K, Behrendt N, Brunner N, Ellis V, Ploug M, Pyke C. The urokinse receptor. Protein structure and role in plasminogen activation and cancer invasion. Fibrinolysis. 1994;8:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassalli JD. The urokinase receptor. Fibrinolysis. 1994;8:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman HA. Plasminogen activators, integrins, and the coordinated regulation of cell adhesion and migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:714–724. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Y, Lukashev M, Simon DI, et al. Regulation of integrin function by the urokinase receptor. Science. 1996;273:1551–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei Y, Waltz DA, Rao N, Drummond RJ, Rosenberg S, Chapman HA. Identification of the urokinase receptor as an adhesion receptor for vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32380–32388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ossowski L, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Urokinase receptor and integrin partnership: coordination of signaling for cell adhesion, migration and growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:613–620. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolon I, Gouyer V, Devouassoux M, et al. Expression of c-ets-1, collagenase 1, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator genes in lung carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1298–1310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolon I, Devouassoux M, Robert C, Moro D, Brambilla C, Brambilla E. Expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator, stromelysin 1, stromelysin 3, and matrilysin genes in lung carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1619–1629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert C, Bolon I, Gazzeri S, Veyrenc S, Brambilla C, Brambilla E. Expression of plasminogen activator inhibitors 1 and 2 in lung cancer and their role in tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2094–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ignar DM, Andrews JL, Witherspoon SM, et al. Inhibition of establishment of primary and micrometastatic tumors by a urokinase plasminogen activator receptor antagonist. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16:9–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1006503816792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamenkovic I. Extracellular matrix remodelling: the role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol. 2003;200:448–464. doi: 10.1002/path.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vihinen P, Kahari VM. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer: prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:157–166. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown PD, Bloxidge RE, Stuart NS, Gatter KC, Carmichael J. Association between expression of activated 72-kilodalton gelatinase and tumor spread in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:574–578. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Avila G, Iturria C, Vadillo F, Teran L, Selman M, Perez-Tamayo R. 72-kD (MMP-2) and 92-kD (MMP-9) type IV collagenase production and activity in different histologic types of lung cancer cells. Pathobiology. 1998;66:5–16. doi: 10.1159/000027989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbanski SJ, Edwards DR, Maitland A, Leco KJ, Watson A, Kossakowska AE. Expression of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in primary pulmonary carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:1188–1194. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodate M, Kasai T, Hashimoto H, Yasumoto K, Iwata Y, Manabe H. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase (gelatinase) in T1 adenocarcinoma of the lung. Pathol Int. 1997;47:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1997.tb04525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nawrocki B, Polette M, Marchand V, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human bronchopulmonary carcinomas: quantificative and morphological analyses. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:556–564. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970807)72:4<556::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki M, Iizasa T, Fujisawa T, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases in non-small-cell lung cancer. Invasion Metastasis. 1998;18:134–141. doi: 10.1159/000024506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sienel W, Hellers J, Morresi-Hauf A, et al. Prognostic impact of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in operable non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:647–651. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakka SS, Rajagopal R, Rajan MK, et al. Adenovirus-mediated antisense urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor gene transfer reduces tumor cell invasion and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakka SS, Gondi CS, Yanamandra N, et al. Synergistic down-regulation of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in SNB19 glioblastoma cells efficiently inhibits glioma cell invasion, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2454–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer GD, Gouze E, Gouze JN, Betz OB, Evans CH, Ghivizzani SC. Gene transfer to articular chondrocytes with recombinant adenovirus. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;215:235–246. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-345-3:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller-Klieser W. Three-dimensional cell cultures: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1109–C1123. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bugge TH, Kombrinck KW, Xiao Q, et al. Growth and dissemination of Lewis lung carcinoma in plasminogen-deficient mice. Blood. 1997;90:4522–4531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson IC, Shipp MA, Docherty AJP, Teicher BA. Combination therapy including a gelatinase inhibitor and cytotoxic agent reduces local invasion and metastasis of murine Lewis lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:715–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andreasen PA, Kjoller L, Christensen L, Duffy MJ. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator system in cancer metastasis: a review. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:1–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970703)72:1<1::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato H, Kida Y, Mai M, et al. Expression of genes encoding type IV collagen-degrading metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in various human tumor cells. Oncogene. 1992;7:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller D, Breathnach R, Engelmann A, et al. Expression of collagenase-related metalloproteinase genes in human lung or head and neck tumours. Int J Cancer. 1991;%19;48:550–556. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerbel RS, Rak J, Kobayashi H, Man MS, St Croix B, Graham CH. Multicellular resistance: a new paradigm to explain aspects of acquired drug resistance of solid tumors. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:661–672. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips RM, Clayton MR. Plateau-phase cultures: an experimental model for identifying drugs which are bioactivated within the microenvironment of solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:196–201. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bredin CG, Liu Z, Hauzenberger D, Klominek J. Growth-factor-dependent migration of human lung-cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:338–345. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990730)82:3<338::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vignaud JM, Martinet Y, Martinet N. Role of growth factors in the stromal reaction in non-small cell lung carcinoma. In: Brambilla C, Brambilla E, editors. Lung Tumors. Fundamental Biology and Clinical Management. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1998. p.347–64.

- 36.Taipale J, Keski-Oja J. Growth factors in the extracellular matrix. FASEB J. 1997;11:51–59. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.1.9034166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bredin CG, Liu Z, Klominek J. Growth factor-enhanced expression and activity of matrix metalloproteases in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4877–4884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pei XH, Nakanishi Y, Takayama K, Bai F, Hara N. Granulocyte, granulocyte-macrophage, and macrophage colony-stimulating factors can stimulate the invasive capacity of human lung cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:40–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Lu H, Griscelli F, et al. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of a uPA/uPAR antagonist suppresses angiogenesis-dependent tumor growth and dissemination in mice. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1105–1113. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Griscelli F, Lindenmeyer F, et al. Systemic delivery of antiangiogenic adenovirus AdmATF induces liver resistance to metastasis and prolongs survival of mice. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:3045–3053. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim J, Yu W, Kovalski K, Ossowski L. Requirement for specific proteases in cancer cell intravasation as revealed by a novel semiquantitative PCR-based assay. Cell. 1998;94:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mira E, Lacalle RA, Buesa JM, et al. Secreted MMP9 promotes angiogenesis more efficiently than constitutive active MMP9 bound to the tumor cell surface. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1847–1857. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonomi P. Matrix metalloproteinases and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:78–86. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.31528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto A, Yano S, Shiraga M, et al. A third-generation matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor (ONO-4817) combined with docetaxel suppresses progression of lung micrometastasis of MMP-expressing tumor cells in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:822–828. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, Tsao MS, Pagura M, et al. Early combined treatment with carboplatin and the MMP inhibitor, prinomastat, prolongs survival and reduces systemic metastasis in an aggressive orthotopic lung cancer model. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCawley LJ, Crawford HC, King LE, Jr, Mudgett J, Matrisian LM. A protective role for matrix metalloproteinase-3 in squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6965–6972. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bissell MJ, Radisky D. Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fibbi G, Caldini R, Chevanne M, et al. Urokinase-dependent angiogenesis in vitro and diacylglycerol production are blocked by antisense oligonucleotides against the urokinase receptor. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1109–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koolwijk P, van Erck MG, de Vree WJ, et al. Cooperative effect of TNFalpha, bFGF, and VEGF on the formation of tubular structures of human microvascular endothelial cells in a fibrin matrix. Role of urokinase activity. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:1177–1188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koolwijk P, Sidenius N, Peters E, et al. Proteolysis of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor by metalloproteinase-12: implication for angiogenesis in fibrin matrices. Blood. 2001;97:3123–3131. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazar AP, Henkin J, Goldfarb RH. The urokinase plasminogen activator system in cancer: implications for tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:15–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1009095825561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu H, Mabilat C, Yeh P, et al. Blockage of urokinase receptor reduces in vitro the motility and the deformability of endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;380:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Min HY, Doyle LV, Vitt CR, et al. Urokinase receptor antagonists inhibit angiogenesis and primary tumor growth in syngeneic mice. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2428–2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasunaga C, Nakashima Y, Sueishi K. A role of fibrinolytic activity in angiogenesis. Quantitative assay using in vitro method. Lab Invest. 1989;61:698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Itoh T, Tanioka M, Yoshida H, Yoshioka T, Nishimoto H, Itohara S. Reduced angiogenesis and tumor progression in gelatinase A-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1048–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis: a moving target for therapeutic intervention. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1237–1241. doi: 10.1172/JCI6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinto CA, Carvalho PE, Antonangelo L, et al. Morphometric evaluation of tumor matrix metalloproteinase 9 predicts survival after surgical resection of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3098–3104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1994;79:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Engbring JA, Kleinman HK. The basement membrane matrix in malignancy. J Pathol. 2003;200:465–470. doi: 10.1002/path.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rabbani SA, Mazar AP. The role of the plasminogen activation system in angiogenesis and metastasis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2001;10:393–415. x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lund LR, Romer J, Bugge TH, et al. Functional overlap between two classes of matrix-degrading proteases in wound healing. EMBO J. 1999;18:4645–4656. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]