Abstract

Photoreactivation of Escherichia coli after inactivation by a low-pressure (LP) UV lamp (254 nm), by a medium-pressure (MP) UV lamp (220 to 580 nm), or by a filtered medium-pressure (MPF) UV lamp (300 to 580 nm) was investigated. An endonuclease sensitive site (ESS) assay was used to determine the number of UV-induced pyrimidine dimers in the genomic DNA of E. coli, while a conventional cultivation assay was used to investigate the colony-forming ability (CFA) of E. coli. In photoreactivation experiments, more than 80% of the pyrimidine dimers induced by LP or MPF UV irradiation were repaired, while almost no repair of dimers was observed after MP UV exposure. The CFA ratios of E. coli recovered so that they were equivalent to 0.9-, 2.3-, and 1.7-log inactivation after 3-log inactivation by LP, MP, and MPF UV irradiation, respectively. Photorepair treatment of DNA in vitro suggested that among the MP UV emissions, wavelengths of 220 to 300 nm reduced the subsequent photorepair of ESS, possibly by causing a disorder in endogenous photolyase, an enzyme specific for photoreactivation. On the other hand, the MP UV irradiation at wavelengths between 300 and 580 nm was observed to play an important role in reducing the subsequent recovery of CFA by inducing damage other than damage to pyrimidine dimers. Therefore, it was found that inactivating light at a broad range of wavelengths effectively reduced subsequent photoreactivation, which could be an advantage that MP UV irradiation has over conventional LP UV irradiation.

UV irradiation is one of the effective treatments used for disinfection. The numbers of water and wastewater treatment plants equipped with UV disinfection systems have been increasing in the past few decades in many countries, because such a system is easy to maintain, needs no chemical input, and produces no hazardous by-products (21). The ability of UV light to inactivate microorganisms (in other words, the sensitivity of microorganisms to UV light) is known to differ from organism to organism (1, 14, 25). Many researchers have pointed out that parasites such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia, the most problematic waterborne pathogens, can be inactivated effectively by UV irradiation (1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 15). This should be a great advantage of UV disinfection systems, because such parasites are known to be highly resistant to conventional chemical disinfectants, such as chlorine.

The mechanisms by which UV light inactivates microorganisms are different at different wavelengths (14). The germicidal effect of short-wavelength UV light (UV-C and UV-B; 220 to 320 nm) is mainly due to the formation of cis-syn cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in the genome DNA of the organisms, while (6-4) photoproducts and other photoproducts are also produced at lower ratios (4, 14). The lesions inhibit the normal replication of the genome and result in inactivation of the microorganisms. Besides genomes, proteins and enzymes with unsaturated bonds are known to absorb UV-C and UV-B, which may also result in significant damage to the organisms (17). On the other hand, long-wavelength UV light (UV-A; 320 to 400 nm) is known to damage organisms mainly by exciting photosensitive molecules inside the cell to produce active species such as O2˙−, H2O2, and ˙OH, which damage the genome and other intracellular molecules and cause lethal and sublethal effects, such as mutations and growth delay (8, 16, 22, 23, 24).

Some organisms are known to possess mechanisms to repair UV-damaged DNA. Photoreactivation is one DNA repair mechanism, while other mechanisms are commonly referred to as dark repair in contrast to photoreactivation (11). Special attention has been paid to photoreactivation because it may greatly impair the efficacy of UV disinfection within a few hours after treatment. Photoreactivation is the phenomenon by which UV-inactivated organisms regain their activity via photorepair of UV-induced lesions in the DNA by utilizing the energy of near-UV light (310 to 480 nm) and an enzyme, photolyase (11, 14). Therefore, UV-A is essential for photoreactivation, although it also has lethal and sublethal effects on organisms, as mentioned above. Jagger called this phenomenon concomitant photoreactivation because the inactivating light itself has the potential to photorepair the dimers (16). The ability to perform photoreactivation differs from species to species, and most strains of Escherichia coli, the indicator bacterium used in water quality control, are known to be capable of photoreactivation. The photolyase of E. coli is basically specific for repair of pyrimidine dimers, while some organisms were recently found to have a photoreactivating enzyme specific for (6-4) photoproducts (19, 27, 28). The diversity and distribution of photolyase are still controversial issues, and it is therefore important to investigate the photoreactivation ability of key microorganisms, such as indicator bacteria. Moreover, quantitative determination of photoreactivation is essential in order to be able to calculate the UV doses necessary to compensate for the potential repair in advance.

The most conventional UV lamps used for disinfection are low-pressure (LP) UV lamps, while medium-pressure (MP) UV lamps have also been used. LP UV lamps have monochromatic emission at a wavelength of 254 nm, which is most efficiently absorbed by DNA bases and therefore has some of the greatest germicidal effects among UV wavelengths (14). On the other hand, MP UV lamps emit polychromatic light at a broad range of wavelengths, from around 200 to 600 nm. MP UV lamps can emit light at a high intensity, which allows MP UV systems to be operated at higher flow rates than LP UV systems (12, 17). MP UV lamps are known to be as effective as conventional LP UV lamps at inactivating microorganisms or more effective (6, 7, 13), and the photoreactivation that occurs after MP UV disinfection results in a requirement for further inactivation because of its importance.

The purpose of this study was to compare a polychromatic MP UV lamp (220 to 580 nm) with a monochromatic LP UV lamp (254 nm) in terms of photoreactivation of E. coli. In addition, photoreactivation of E. coli after exposure to a filtered MP (MPF) UV lamp (300 to 580 nm) was also investigated in order to clarify the effects of inactivating light wavelengths on the subsequent photoreactivation. An endonuclease sensitive site (ESS) assay, which previously proved to be useful for determining the number of pyrimidine dimers in the genomic DNA of E. coli (20), was used along with a conventional cultivation assay in order to investigate UV inactivation and subsequent photoreactivation of E. coli both at the genomic level and at the colony-forming-ability (CFA) level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganism.

A pure culture of E. coli K-12 strain IFO 3301 was used as the test microorganism. A few discrete colonies of E. coli were selected from growth formed on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (Merck) and were incubated in LB broth (Difco) at 37°C overnight until the stationary phase was reached. The growth was collected by centrifugation (7,000 × g, 10 min), washed twice with a sterilized phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.6), and subsequently suspended in the phosphate buffer at an initial concentration of 2.5 × 107 to 4.0 × 107 CFU · ml−1. Forty milliliters of the suspension of E. coli was placed into a sterilized petri dish (diameter, 100 mm) and subjected to the light exposure procedures.

Light exposure.

Two LP UV lamps (20 W; Stanley GL6; Toshiba) or an MP UV lamp (330 W; B410MW; Ebara) was used for inactivation. In order to investigate the effect of long wavelengths, the MP UV lamp emission was filtered through a Pyrex glass plate (thickness, 1 mm). A multichannel photodetector (MCPD-2000; Otsuka) showed that the emissions of the LP, MP, and MPF UV lamps were at wavelengths of 254, 220 to 580, and 300 to 580 nm, respectively. The germicidal intensity of the light emitted from each lamp was standardized by determining the irradiance of light at 254 nm with a biodosimeter by using F-specific RNA coliphage Qβ (18). Briefly, a pure-culture suspension of phage Qβ at an initial concentration of 2.0 × 106 PFU · ml−1 was exposed to the LP, MP, and MPF UV lamps to determine the inactivation curves by a double-agar-layer method with LB agar (Merck) by using E. coli K-12 strain F+ A/λ as the host organism. The rate of inactivation of phage Qβ for each lamp was compared with the inactivation rate constant for phage Qβ at 254 nm to determine the irradiance values for the LP, MP, and MPF UV lamps (0.24, 3.0, and 0.25 mW · cm−2, respectively). The irradiance values were fixed throughout the experiment, and UV doses were controlled by changing the exposure time.

Each 99.9% (3-log) inactivation of the CFA ratio (see below) was followed by exposure to fluorescent lamps (18 W; Hitachi) for 3 h to allow photoreactivation. The irradiance of the photoreactivating light at 360 nm was 0.1 mW · cm−2, as measured with a UV radiometer (UVR-2 UD-36; Topcon). All preparations of E. coli were constantly stirred magnetically throughout the experiment and kept in the dark except during exposure to UV and fluorescent light. The sample temperature was kept at 20°C by circulating cooling water around the petri dishes.

Cultivation assay.

The CFA of E. coli was investigated by using a deoxycholate acid agar medium (Eiken) in a dark room and the standard methods for examination of water (30). The number of CFU after incubation at 37°C for 18 h was determined, and the ratio of the CFA of E. coli was calculated as follows:  , where CFAt is the ratio of CFA at irradiation time t, Nt is the number of CFU at irradiation time t, and N0 is the number of CFU before UV irradiation.

, where CFAt is the ratio of CFA at irradiation time t, Nt is the number of CFU at irradiation time t, and N0 is the number of CFU before UV irradiation.

ESS assay.

An ESS assay allows recognition of pyrimidine dimers in DNA at ESS by treatment of DNA with a UV endonuclease, which incises a phosphodiester bond specifically at the site of a pyrimidine dimer. The molecular lengths of fragmented DNA are determined by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by a theoretical calculation to obtain the number of ESS (26).

The conditions for the ESS assay used in this study were basically the same as those described previously (20). After the irradiation procedures, the E. coli suspensions were centrifuged (5,000 × g, 10 min), and the pellets were subjected to DNA extraction procedures (Genomic-tip; Qiagen). The extracted DNA was concentrated by using centrifugal filter devices (Centricon; Millipore) and resuspended in a UV endonuclease buffer containing 30 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 40 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA. The DNA preparations were treated with a UV endonuclease from Micrococcus luteus, prepared by the method of Carrier and Setlow (3), at 37°C for 45 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of an alkaline loading dye preparation containing (final concentrations) 100 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5% Ficoll, and 0.05% bromocresol green. The DNA samples were electrophoresed at 0.5 V/cm for 16 h on 0.5% alkaline agarose gels in an alkaline buffer containing 30 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA along with two molecular length standards, T4dC+T4dC/BglI digest mixture (7GT; Wako) and T4dC+T4dC/BglII digest mixture (8GT; Wako). After electrophoresis, the gels were stained in a 0.5-μg/ml solution of ethidium bromide, photographed, and analyzed (Gel Doc 1000 Molecular Analyst; Bio-Rad). The midpoint of the mass of DNA was photographically determined by determining the median migration distance of each sample, which was converted into the median molecular length (Lmed) of the DNA relative to the migration patterns of the molecular length standards. The average molecular length (Ln) of the DNA was obtained by using the equation of Veatch and Okada (29):  .

.

The number of ESS per base was calculated as follows (9):  , where Ln(+UV) and Ln(−UV) are the average molecular lengths of UV-irradiated and nonirradiated samples, respectively.

, where Ln(+UV) and Ln(−UV) are the average molecular lengths of UV-irradiated and nonirradiated samples, respectively.

The ESS remaining ratio, the ratio of the number of ESS during fluorescent light exposure to the number of ESS before fluorescent light exposure, was defined as follows:  , where t is the time of exposure to the fluorescent light irradiation and t0 is zero time.

, where t is the time of exposure to the fluorescent light irradiation and t0 is zero time.

Photorepair treatment of DNA in vitro.

A solution of E. coli photolyase was prepared from nonirradiated E. coli by using the method of Friedberg and Hanawalt (10). Briefly, 5 × 109 cells of E. coli K-12 were lysed by sonication (20 passes at 70% output; model W185 sonifier; Branson) on ice and centrifuged (120,000 × g, 60 min), and this was followed by ammonium sulfate precipitation and chromatography purification by using a 25-ml phenyl-Sepharose column (CL-4B; Sigma) and a 20-ml hydroxylapatite column (Bio-Gel HT; Bio-Rad). The purified photolyase solution was confirmed not to be contaminated with other DNA repair enzymes for dark repair by repair treatment of ESS in vitro without exposure to fluorescent light. Some of the photolyase solution was directly exposed to the MP UV lamp in vitro at a dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2 to obtain MP UV-exposed photolyase. Separate from the photolyase preparation, the genomic DNA of E. coli was extracted from an E. coli suspension previously exposed to an MP UV lamp in vivo at a dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2. The extracted DNA was suspended in the UV endonuclease buffer solution as described above and was mixed with the intact or the MP UV-exposed photolyase; this was followed by immediate exposure to the fluorescent light in vitro at 37°C for 45 min. Subsequently, the DNA-photolyase mixtures were subjected to the ESS assay as described above to determine the number of ESS after the photorepair treatment in vitro.

RESULTS

Inactivation by LP, MP, or MPF UV lamp.

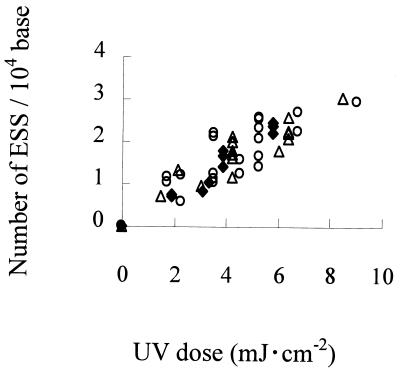

Figure 1 shows typical gel images of ESS assay mixtures for E. coli exposed to an LP, MP, or MPF UV lamp, indicating that higher UV doses resulted in fragmentation of DNA into shorter molecules. Figure 1 was analyzed to obtain Fig. 2, which shows profiles of the numbers of ESS in E. coli during exposure to LP, MP, or MPF UV. As shown in this figure, the number of ESS induced by UV irradiation increased along with the increase in UV doses from each lamp. Figure 3 shows the ratio of CFA during exposure of E. coli to LP, MP, or MPF UV. The CFA ratio decreased log linearly with increasing UV doses for all lamps. There was no clear difference among LP UV irradiation, MP UV irradiation, and MPF UV irradiation in terms of the ESS and CFA profiles for UV doses during inactivation procedures, as shown in Fig. 2 and 3.

FIG. 1.

Gel images for ESS assays of E. coli during exposure to LP, MP, or MPF UV lamps. (A) Exposure to LP UV. Lanes 1 and 2, standard markers; lane 3, no UV; lanes 4 to 6, UV doses of 1.9, 3.8, and 5.7 mJ · cm−2, respectively. (B) Exposure to MP UV. Lanes 1 and 6, standard marker; lane 2, no UV; lanes 3 to 5, UV doses of 2.1, 4.2, and 6.3 mJ · cm−2, respectively. (C) Exposure to MPF UV. Lane 1, standard marker; lane 2, no UV; lanes 3 to 5, UV doses of 1.8, 3.6, and 5.4 mJ · cm−2, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Numbers of ESS in E. coli after exposure to an LP UV lamp (♦), an MP UV lamp (▵), or an MPF UV lamp (○). The data are the results of five independent exposures to each type of lamp.

FIG. 3.

CFA ratios for E. coli after exposure to an LP UV lamp (♦), an MP UV lamp (▵), or an MPF UV lamp (○). The data are the results of five independent exposures to each type of lamp.

Figure 4 shows the relationships between the number of ESS and the CFA ratio during exposure to LP, MP, or MPF UV. The CFA ratio showed a log-linear relationship with the number of ESS for each type of lamp, while the ESS-CFA relationships did not differ significantly among LP UV exposure, MP UV exposure, and MPF UV exposure.

FIG. 4.

Relationships between the numbers of ESS and the CFA ratios for E. coli after exposure to an LP UV lamp (♦), an MP UV lamp (▵), or an MPF UV lamp (○). The data are the results of five independent exposures to each type of lamp.

Photoreactivation after LP, MP, or MPF UV inactivation.

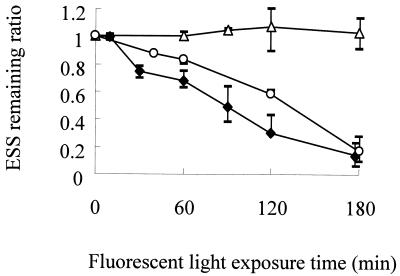

Figure 5 shows typical gel images of ESS assay mixtures for E. coli during fluorescent light exposure after LP, MP, or MPF UV exposure, which were analyzed to determine the ESS remaining ratio, as shown in Fig. 6. The ESS induced by LP and MPF UV irradiation were gradually repaired during fluorescent light exposure; on average, 84 and 83% of the total ESS were repaired in 3 h, respectively. On the other hand, almost no ESS were repaired by fluorescent light exposure after MP UV irradiation.

FIG. 5.

Gel images for ESS assays of E. coli after exposure to fluorescent light after LP, MP, or MPF UV inactivation. (A) Exposure to LP UV. Lane 1, standard marker; lane 2, no UV; lane 3, UV dose of 5.7 mJ · cm−2; lanes 4 to 8, UV dose of 5.7 mJ · cm−2, followed by exposure to fluorescent light for 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min, respectively. (B) Exposure to MP UV. Lane 1, no UV; lane 2, UV dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2; lanes 3 to 6, UV dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2, followed by exposure to fluorescent light for 60, 90, 120, and 180 min, respectively; lane 7, standard marker. (C) Exposure to MPF UV. Lane 1, standard marker; lane 2, no UV; lane 3, UV dose of 5.4 mJ · cm−2; lanes 4 to 6, UV dose of 5.4 mJ · cm−2, followed by exposure to fluorescent light for 60, 120, and 180 min, respectively.

FIG. 6.

ESS remaining ratios after exposure to fluorescent light after LP UV (♦), MP UV (▵), or MPF UV (○) inactivation. The symbols indicate the means from two or three independent experiments, and the bars indicate the maximum and minimum values.

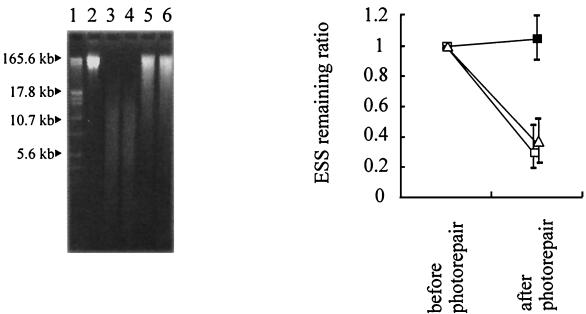

Figure 7 shows the results of photorepair treatment in vivo, in vitro with intact photolyase, and in vitro with MP UV-exposed photolyase. This figure shows that MP UV-induced ESS in E. coli were photorepaired in vitro with either intact or MP UV-exposed photolyase, suggesting that no repair of ESS in vivo was caused by a disorder with the endogenous photolyase of MP UV-irradiated E. coli.

FIG. 7.

Photorepair of ESS in vivo (▪), in vitro with intact photolyase (□), or in vitro with MP-exposed photolyase (▵) after MP inactivation. Lane 1, standard marker; lane 2, no UV; lane 3, MP UV dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2; lane 4, MP UV dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2, followed by photorepair in vivo; lanes 5 and 6, MP UV dose of 6.3 mJ · cm−2, followed by photorepair in vitro with intact photolyase (lane 5) or with MP-exposed photolyase (lane 6). For photorepair in vivo, MP UV-irradiated E. coli was subsequently exposed to fluorescent light. For photorepair in vitro, DNA of MP UV-irradiated E. coli was exposed to fluorescent light in vitro with intact or MP UV-exposed photolyase. The symbols indicate the means from two or three independent experiments, and the bars indicate the maximum and minimum values.

Figure 8 shows the profiles of the CFA ratio of E. coli during fluorescent light exposure after LP, MP, or MPF UV inactivation. After 3-log inactivation by exposure to LP and MPF UV, the CFA ratio recovered so that on average it was equivalent to 0.9- and 1.7-log inactivation, respectively, after exposure to fluorescent light for 3 h. After 3-log inactivation by MP UV irradiation, on the other hand, the CFA ratio showed little recovery and on average was equivalent to 2.3-log inactivation after 3 h of exposure to fluorescent light. Characteristics of photoreactivation after exposure to LP, MP, or MPF UV are summarized in Table 1. The relationships between the ESS remaining ratio and the CFA ratio after LP, MP, or MPF UV inactivation are shown in Fig. 9.

FIG. 8.

CFA ratios after exposure to fluorescent light after LP UV (♦), MP UV (▵), or MPF UV (○) inactivation. The symbols indicate the means from two or three independent experiments, and the bars indicate the maximum and minimum values.

TABLE 1.

Photoreactivation characteristics of E. coli after LP, MP, or MPF UV inactivation

| Irradiation | Repaired ESS (%) | Repaired CFAa (log10) | Final inactivation of CFAb (log10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LP UV | 84.2 (72.6-94.8)c | 2.09 (2.00-2.18) | 0.92 (0.83-1.02) |

| MP UV | <0 (<0-3.2) | 0.61 (0.53-0.83) | 2.29 (2.07-2.51) |

| MPF UV | 83.1 (75.1-93.1) | 1.02 (0.95-1.38) | 1.70 (1.67-1.73) |

Log (CFA ratio after photoreactivation) − log (CFA ratio before photoreactivation).

−Log (CFA ratio after photoreactivation).

Mean based on two or three independent experiments. The values in parentheses are minimum and maximum values.

FIG. 9.

Relationships between the ESS remaining ratios and the CFA ratios after exposure to fluorescent light after LP UV (♦), MP UV (▵), or MPF UV (○) inactivation. The data indicate three independent results for each type of lamp.

DISCUSSION

During UV exposure, no clear difference was observed among LP, MP, and MPF UV lamps in terms of the ESS and CFA profiles for UV doses determined with the biodosimeter, as shown in Fig. 2 and 3. This suggests that the mechanisms by which LP, MP, and MPF UV lamps inactivate bacteriophage Qβ and E. coli were similar in terms of ESS formation as well as in terms of the decrease in CFA. In addition, Fig. 2 and 3 suggest that the UV-A light included in the MP and MPF UV lamp emissions did not cause concomitant photoreactivation during inactivation procedures under our experimental conditions. This is probably because the time of exposure to the MP or MPF UV lamps was too short to utilize the UV-A light for repair, considering that the time commonly required to complete photoreactivation is 1 to 3 h. Photoreactivation seems to be more dependent on the time of exposure to photoreactivating light than to the irradiance of the light, probably because the limiting factor in the photorepair mechanism is the frequency of photolyase attachment to the dimers (14).

The ratio of CFA showed log-linear relationships with the number of ESS during exposure to LP, MP, or MPF UV, while the ESS-CFA relationships were not clearly different for the three types of lamps. This suggests that the numbers of ESS necessary to decrease the CFA of E. coli are not significantly different for inactivation with the different wavelengths (254, 220 to 580, and 300 to 580 nm). This may imply that the culturability of E. coli is regulated mostly by pyrimidine dimers and is not greatly affected by other damage during inactivation.

Figure 7 shows that even ESS in MP UV-irradiated E. coli, which were not repaired by exposure to fluorescent light in vivo, were photorepaired in vitro with either intact or MP UV-exposed photolyase. This suggests that the MP UV-induced pyrimidine dimers were not structurally different from other photorepairable dimers and that the failure to repair MP UV-induced ESS in vivo was caused by a disorder with the endogenous photolyase in E. coli. Moreover, even MP UV-exposed photolyase could repair ESS in vitro, indicating that the photolyase itself was not inactivated by MP UV irradiation. It was therefore assumed that MP UV irradiation did not affect the activity of endogenous photolyase but reduced the amount of photolyase in E. coli, possibly by affecting regulation of the photolyase gene to lower expression. The failure in ESS repair was not observed after MPF UV treatment; it was observed only after MP UV treatment. This suggests that the disorder of photolyase was caused by wavelengths between 220 and 300 nm, although it is possible that the difference in irradiance between MP UV and MPF UV affected this phenomenon. The detailed mechanisms of exposure to MP UV that reduce the repair of ESS may be an interesting subject for further investigation. The results of photorepair treatment in vitro suggested that the MP UV lamp was effective at reducing the subsequent photorepair of pyrimidine dimers at the enzyme level.

Table 1 and Fig. 9 show that both the repair of ESS and the recovery of CFA were observed after exposure to LP or MPF UV, while neither was apparently observed after exposure to MP UV irradiation. Table 1 and Fig. 9 also indicate that MPF UV resulted in less recovery of CFA than LP UV, although the levels of repair of ESS were equivalent after exposure to LP UV and after exposure to MPF UV, suggesting that the contribution of ESS repair to CFA recovery was less after exposure to MPF UV than after exposure to LP UV. This implies that exposure to MPF UV induced more damage besides pyrimidine dimer damage than exposure to LP UV irradiation induced; the latter reduced the recovery of CFA even after the repair of ESS. Among the MPF UV emissions, UV-A (320 to 400 nm) may play an important role in this respect because UV-A indirectly damages organisms through active species. As discussed above (Fig. 4), the ESS-CFA relationships of LP UV and MPF UV were not significantly different in terms of inactivation procedures, and it was therefore assumed that the culturability was regulated mostly by pyrimidine dimers and was not greatly affected by other damage during inactivation. On the other hand, damage in addition to pyrimidine dimer damage was thought to play an important role in the recovery of culturability during photoreactivation procedures. These two results can be reasonably explained by considering that pyrimidine dimer damage and other damage were simultaneously produced by exposure to MPF UV but only pyrimidine dimer damage could be photorepaired by exposure to fluorescent light. Simultaneous formation of pyrimidine dimers and other compounds may have occurred during exposure to MP UV as well, although even pyrimidine dimers could not be photorepaired in this case because of the disorder with photolyase, as discussed above.

In summary, the MP UV lamp was found to be more effective than the LP UV lamp for reducing subsequent photoreactivation of E. coli both in terms of photorepair of ESS and in terms of recovery of CFA. Among the emissions of the MP UV lamp, wavelengths from 220 to 300 nm were found to reduce the subsequent photorepair of pyrimidine dimers, possibly by causing a disorder with endogenous photolyase, while wavelengths between 300 and 580 nm were found to play an important role in reducing the recovery of culturability by inducing damage other than pyrimidine dimer damage. It was therefore concluded that inactivating light at a broad range of wavelengths was effective for reducing subsequent photoreactivation of E. coli, which could be an advantage that MP UV lamps have over conventional LP UV lamps from the viewpoint of photoreactivation control.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiroshi Mitani (Department of Integrated Bioscience, University of Tokyo) for his contribution to the photorepair treatment in vitro.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbaszadegan, M., M. N. Hasan, C. P. Gerba, P. F. Roessler, B. R. Wilson, R. Kuennen, and E. V. Dellen. 1997. The disinfection efficacy of a point-of-use water treatment system against bacterial, viral and protozoan waterborne pathogens. Water Res. 31:574-582. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukhari, Z., T. M. Hargy, J. R. Bolton, B. Dussert, and J. L. Clancy. 1999. Medium-pressure UV for oocyst inactivation. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 91:86-94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrier, W. L., and R. B. Setlow. 1970. Endonuclease from Micrococcus luteus which has activity toward ultraviolet-irradiated deoxyribonucleic acid: purification and properties. J. Bacteriol. 102:178-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrasekhar, D., and B. Houten. 2000. In vivo formation and repair of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and 6-4 photoproducts measured at the gene and nucleotide level in Escherichia coli. Mutat. Res. 450:19-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clancy, J. L., T. M. Hargy, M. M. Marshall, and J. E. Dyksen. 1998. UV light inactivation of Cryptosporidium oocysts. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 90:92-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craik, S. A., D. Weldon, G. R. Finch, J. R. Bolton, and M. Belosevic. 2001. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using medium- and low-pressure ultraviolet radiation. Water Res. 35:1387-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craik, S. A., G. R. Finch, J. R. Bolton, and M. Belosevic. 2000. Inactivation of Giardia muris cysts using medium-pressure ultraviolet radiation in filtered drinking water. Water Res. 34:4325-4332. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Didier, C., J. P. Pouget, J. Cadet, A. Favier, J. C. Beani, and M. J. Richard. 2001. Modulation of exogenous and endogenous levels of thirodoxin in human skin fibroblasts prevents DNA damaging effect of ultraviolet A radiation. Free Radical Biol. Med. 30:537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman, S. E., A. D. Blackett, D. C. Monteleone, R. B. Setlow, B. M. Sutherland, and J. C. Sutherland. 1986. Quantitation of radiation-, chemical-, or enzyme-induced single strand breaks in nonradioactive DNA by alkaline gel electrophoresis: application of pyrimidine dimers. Anal. Biochem. 158:119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedberg, E. C., and P. Hanawalt. 1988. DNA repair: a laboratory manual of research procedures, vol. 3, p. 461-478. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 11.Friedberg, E. R., G. C. Walker, and W. Siede. 1995. DNA repair and mutagenesis, p. 92-107. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Gehr, R., and H. Wright. 1998. UV disinfection of wastewater coagulated with ferric chloride: recalcitrance and fouling problems. Water Sci. Technol. 38:15-23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giese, N., and J. Darby. 2000. Sensitivity of microorganisms to different wavelengths of UV light: implications on modeling of medium pressure UV system. Water Res. 34:4007-4013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harm, W. 1980. Biological effects of ultraviolet radiation, p. 31-39. Cambridge University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 15.Huffman, D. E., T. R. Slifko, K. Salisbury, and J. B. Rose. 2000. Inactivation of bacteria, virus and Cryptosporidium by a point-of-use device using pulsed broad spectrum white light. Water Res. 34:2491-2498. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagger, J. 1981. Near-UV radiation effects on microorganisms. Photochem. Photobiol. 34:761-768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalisvaart, B. F. 2001. Photobiological effects of polychromatic medium pressure UV lamps. Water Sci. Technol. 43:191-197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamiko, N., and S. Ohgaki. 1989. RNA coliphages Qβ as a bioindicator of the UV disinfection efficiency. Water Sci. Technol. 21:227-231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, S. T., K. Malhotra, J. S. Taylor, and A. Sancar. 1996. Purification and partial characterization of (6-4) photoproduct DNA photolyase from Xenopus laevis. Photochem. Photobiol. 63:292-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oguma, K., H. Katayama, H. Mitani, S. Morita, T. Hirata, and S. Ohgaki. 2001. Determination of pyrimidine dimers in Escherichia coli and Cryptosporidium parvum during UV light inactivation, photoreactivation, and dark repair. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4630-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oppenheimer, J. A., J. G. Jacangelo, J.-M. Laine, and J. E. Hoagland. 1997. Testing the equivalency of ultraviolet light and chlorine for disinfection of wastewater to reclamation standards. Water Environ. Res. 69:14-24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oppezzo, O. J., and R. A. Pizarro. 2001. Sublethal effects of ultraviolet A radiation on Enterobacter cloacae. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 62:158-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen, A. B., R. Gniadecki, J. Vicanova, T. Thorn, and H. C. Wulf. 2000. Hydrogen peroxide is responsible for UVA-induced DNA damage measured by alkaline comet assay in HaCaT keratinocytes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 59:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramabhadran, T. V., and J. Jagger. 1976. Mechanism of growth delay induced in Escherichia coli by near ultraviolet radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:59-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommer, R., T. Haider, A. Cabaj, W. Pribil, and M. Lhotsky. 1998. Time dose reciprocity in UV disinfection of water. Water Sci. Technol. 38:145-150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutherland, B. M., and A. G. Shi. 1983. Quantitation of pyrimidine dimer contents of nonradioactive deoxyribonucleic acid by electrophoresis in alkaline agarose gels. Biochemistry 22:745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todo, T., H. Takemori, H. Ryo, M. Ihara, T. Matsunaga, O. Nikaido, K. Sato, and T. Nomura. 1993. A new photoreactivating enzyme that specifically repairs ultraviolet light-induced (6-4) photoproducts. Nature 361:372-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchida, N., H. Mitani, T. Todo, M. Ikenaga, and A. Shima. 1997. Photoreactivating enzyme for (6-4) photoproducts in cultured goldfish cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 65:964-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veatch, W., and S. Okada. 1969. Radiation-induced breaks of DNA in cultured mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 9:330-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Water Works Association. 1993. Standard methods for the examination of water. Japan Water Works Association, Tokyo, Japan.