Abstract

Identification of Bifidobacterium lactis and Bifidobacterium animalis is problematic because of phenotypic and genetic homogeneities and has raised the question of whether they belong to one unique taxon. Analysis of the 16S-23S internally transcribed spacer region of B. lactis DSM10140T, B. animalis ATCC 25527T, and six potential B. lactis strains suggested two distinct clusters. Two specific 16S-23S spacer rRNA gene-targeted primers have been developed for specific detection of B. animalis. All of the molecular techniques used (B. lactis or B. animalis PCR primers, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR) demonstrated that B. lactis and B. animalis form two main groups and suggest a revision of the strains assigned to B. animalis. We propose that B. lactis should be separated from B. animalis at the subspecies level.

Bifidobacterium lactis is used as a probiotic in dairy products (e.g., yoghurt) or supplied in infant food (7, 10). This species was previously described by Meile et al. (8) and characterized by its high oxygen resistance and production of considerable amounts of formate. The phylogenetic position of B. lactis DSM 10140, defined by sequence similarity and sequence analysis of the ldh gene (13), revealed that B. animalis ATCC 25527 is the most closely related strain. Recently, Cai et al. (2) reinvestigated the taxonomic position of B. lactis DSM 10140 and proposed that B. lactis should be considered a junior subjective synonym of B. animalis.

In view of the widespread interest in B. lactis and B. animalis because of the expanding application of these species as probiotics, it is highly desirable to develop a molecular approach to clear and reliable species identification. The rRNA gene (rDNA) has been used widely to infer phylogenetic relationships among bacteria (23). However, as evolutionary distances decrease, the diversity found in the 16S rDNA is often insufficient and genetic relationships of closely related species cannot be accurately defined (1, 11). It has been recently suggested that sequencing of the internally transcribed spacer (ITS) region could overcome this problem since ITS regions might be under less evolutionary pressure and could provide greater genetic variation. Indeed, analysis of this region has already successfully differentiated strains and species of many bacterial groups (1, 3, 4, 9, 17).

We investigated 106 bifidobacterial strains isolated from different environments (Table 1) with recently published B. lactis species-specific primers (20). Six strains gave a specific B. lactis PCR amplicon. By applying the species-specific amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis method to all of the strains, it was possible to allocate them only to the B. animalis-B. lactis cluster (19). The 16S-23S ITS region from each strain was amplified by using primers that annealed to conserved regions of the 16S and 23S genes (primer 16S-for, 5′-GCTAGTAATCGCGGATCAG-3′; primer 23Si, 5′-CATTCGGACACCCTGGGATC-3′). Chromosomal DNA was PCR amplified in accordance with the manufacturer's (Gibco BRL) instructions. Amplicons were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). Nucleotide sequences of PCR products were determined by using the fluorescently labeled primer cycle-sequencing kit (Amersham) and the LI-COR sequencer (MWG). Sequence alignments were done with the Multi-align program, and the ClustalW dendrogram was drawn with the ClustalX program.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used to evaluate the specificity of B. animalis-specific PCR primers by a Multiplex-PCR approach

| Species | Straina | PCR result

|

Origin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ban2- 23SI | Lm3- Lm26 | |||

| B. animalis | ATCC 25527T | + | + | Rat feces |

| B. animalis | ATCC 27672 | + | + | Rat feces |

| B. lactis | DSM 10140T | − | + | Yoghurt |

| B. lactis | NCC 363 | − | + | Human feces |

| B. lactis | NCC 311 | − | + | Human feces |

| B. lactis | NCC 239 | − | + | Human feces |

| B. lactis | NCC 387 | − | + | Infant feces |

| B. lactis | NCC 383 | − | + | Yoghurt |

| B. lactis | NCC 402 | − | + | Yoghurt |

| B. animalis | ATCC 27673 | − | + | Sewage |

| B. animalis | ATCC 27674 | − | + | Rabbit feces |

| B. animalis | ATCC 27536 | − | + | Chicken feces |

| B. adolescentis | ATCC 15703T | − | + | Adult intestine |

| B. adolescentis | ATCC 15704 | − | + | Adult intestine |

| B. bifidum | ATCC 29521T | − | + | Infant feces |

| B. bifidum | ATCC 15696 | − | + | Infant intestine |

| B. breve | ATCC 15700T | − | + | Infant intestine |

| B. breve | ATCC 15701 | − | + | Infant intestine |

| B. catenulatum | ATCC 27539T | − | + | Adult intestine |

| B. coryneforme | DSM20216T | − | + | Honeybee hindgut |

| B. cuniculi | ATCC 27916T | − | + | Rabbit feces |

| B. dentinum | ATCC 27534T | − | + | Dental caries |

| B. infantis | ATCC 15697T | − | + | Infant intestine |

| B. infantis | ATCC 25962 | − | + | Infant intestine |

| B. angulatum | DSM 20098T | − | + | Human feces |

| B. longum | LMG 13197T | − | + | Adult intestine |

| B. magnum | ATCC 27540T | − | + | Rabbit feces |

| B. pseudocate- nulatum | DSM 20438T | − | + | Infant feces |

| B. pseudolongum | DSM 20099T | − | + | Swine feces |

| B. pullorum | DSM 20433T | − | + | Chicken feces |

| B. merycicum | DSM 6492T | − | + | Bovine rumen |

| B. minimum | DSM 20102T | − | + | Sewage |

| B. ruminantium | DSM 6489T | − | + | Bovine rumen |

| B. saeculare | DSM 6531T | − | + | Rabbit feces |

| B. subtile | DSM 20096T | − | + | Sewage |

| B. thermophilum | DSM 20210T | − | + | Swine feces |

| B. asteroides | DSM 20089T | − | + | Honeybee hindgut |

| B. boum | DSM 20432T | − | + | Cattle rumen |

| B. gallicum | DSM 20093T | − | + | Human feces |

| B. gallinarum | DSM 20670T | − | + | Chicken cecum |

| B. inopinatum | DSM 10107T | − | + | Dental plaque |

| B. choerinum | ATCC 27686T | − | + | Swine feces |

| B. suis | ATCC 27533T | − | + | Swine feces |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen; LMG, Bacteria Collection Universiteit Gent; NCC, Nestlé Culture Collection.

For the enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) PCR, primers ERIC-1 (5′-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC-3′) and ERIC-2 (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′) (21) were used. The total reaction mixture of 25 μl contained 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Gibco BRL), 1 μM each primer, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL), and 25 ng of template DNA. Amplifications were carried out with a Perkin-Elmer Cetus 9700 thermal cycler (1 cycle of 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 48°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 4 min; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 6 min). PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels at a constant voltage of 7 V/cm. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and photographed under UV light at 260 nm.

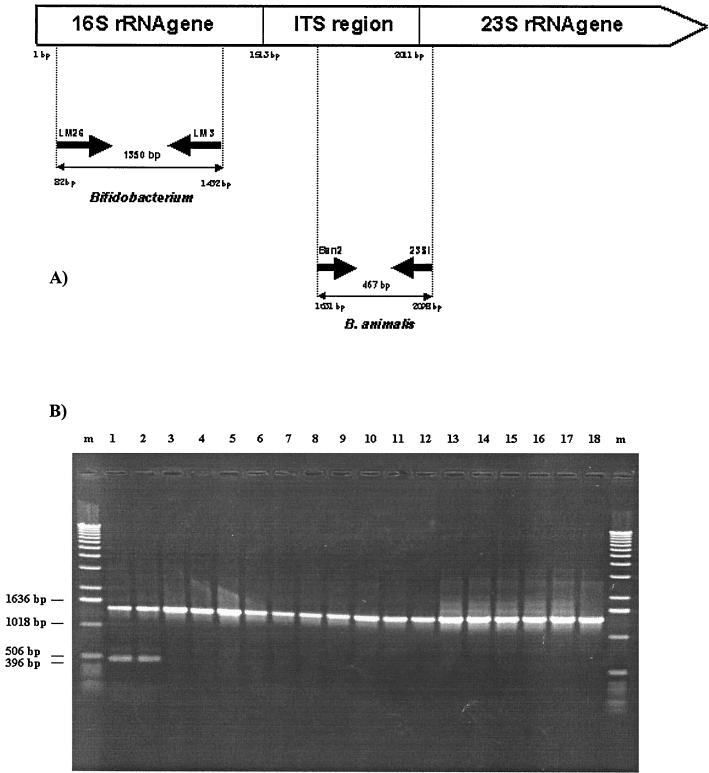

To specifically detect B. animalis strains, we applied a PCR amplification strategy for the ITS regions with primers based on specific B. animalis sequences (see Fig. 5). All PCRs were in a total of 50 μl of a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Gibco BRL), 10 pmol (each) of Lm3 and Lm26 (6), 50 pmol of B. animalis-specific primer Ban2 (5′-CATATTGGATCACGGTCG-3′), 50 pmol of primer 23Si, 25 ng of template DNA, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL). Amplifications were performed with a DNA thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus 9700) as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 7 min. Amplicons were analyzed by 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel electrophoresis in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer at a constant voltage of 7 V/cm and visualized with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) under UV light at 260 nm.

FIG. 5.

(A) Primers and amplification systems used to investigate the species B. animalis. (B) PCR products of various Bifidobacterium species obtained by a Multiplex-PCR approach with B. animalis species-specific PCR primers and bifidobacterial genus-specific primers. (A) The position numbering and expected product sizes are given in accordance with the numbering of the B. animalis 16S-23S spacer region (1). (B) Lanes: 1, B. animalis ATCC 25527; 2, B. animalis ATCC 27672; 3, B. lactis DSM 10140; 4, B. animalis ATCC 27673; 5, B. animalis ATCC 27674; 6, B. animalis ATCC 27536; 7, B. lactis NCC 363; 8, B. lactis NCC 387; 9, B. lactis NCC 402; 10, B. lactis NCC 311; 11, B. lactis NCC 383; 12, B. lactis NCC 239; 13, B. bifidum ATCC 29521; 14, B. breve ATCC 15700; 15, B. longum ATCC 15707; 16, B. infantis ATCC 15679; 17, B. adolescentis ATCC 15703; 18, B. catenulatum ATCC 27539. m, 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco-BRL).

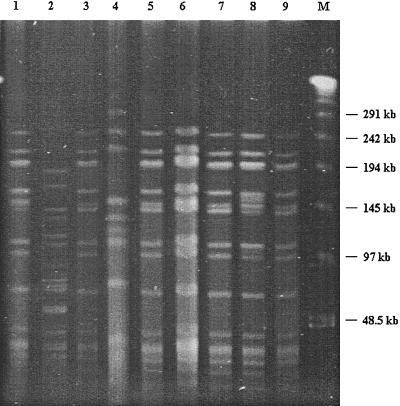

Furthermore, we investigated the strain individuality of all B. animalis and B. lactis isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Agarose-embedded bacterial cells were prepared as described by Walker and Klaenhammer (22). For digestion with restriction endonucleases, cells in agarose blocks were treated with 50 U (each) of XbaI and SpeI (Roche Molecular). Electrophoresis was carried out as previously reported (18).

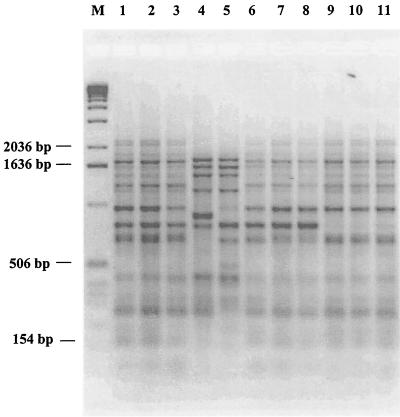

Use of the ERIC-PCR technique resulted in clear identification at the bifidobacterial species level (15; data not shown). ERIC-PCR fingerprints demonstrated that B. lactis NCC 363, NCC 383, NCC 402, and NCC 311 and B. animalis ATCC 27536, ATCC 27673, and ATCC 27674 are not comparable to any other B. animalis strain (e.g., ATCC 25527, ATCC 27672), but they are highly similar to the neotype of the species B. lactis (Fig. 1). B. lactis strains were characterized by DNA restriction patterns with low-frequency cleavage endonucleases and PFGE. Overall, the size estimates for all B. lactis strains were compared with the size estimates for B. animalis ATCC 27673, ATCC 27674, and ATCC 27536 (12). These values were clearly different and unique for each of the B. animalis strains. Only B. lactis NCC 363, NCC 383, NCC 402, and NCC 311 displayed a rather different and unique PFGE profile (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the other two B. lactis isolates (NCC 239 and NCC 387) resulted in SpeI/XbaI PFGE patterns highly similar to that of B. lactis DSM 10140 (data not shown). This indicates that these organisms are very closely related. Indeed, it was demonstrated earlier that these strains are different with additional molecular typing assays such as randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR and triplicate arbitrary primed PCR (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

DNA fingerprint analysis of B. lactis and B. animalis strains by ERIC-PCR. Lanes: 1, B. lactis DSM 10140; 2, B. lactis NCC 363; 3, B. lactis NCC 311; 4, B. animalis ATCC 25527; 5, B. animalis ATCC 27672; 6, B. animalis ATCC 27674; 7, B. animalis ATCC 27536; 8, B. animalis ATCC 27673; 9, B. lactis NCC 383; 10, B. lactis NCC 402; 11, B. lactis NCC 239; M, 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco-BRL).

FIG. 2.

PFGE patterns of genomic DNAs of B. lactis strains after SpeI digestion. Lanes: 1, B. lactis NCC 383; 2, B. lactis NCC 363; 3, B. lactis DSM 10140; 4, B. lactis NCC 402; 5, B. lactis DSM 10140; 6, B. lactis NCC 239; 7, B. lactis NCC 387; 8, B. lactis NCC 311; 9, B. lactis DSM 10140; M, λ DNA ladder (Bio-Rad).

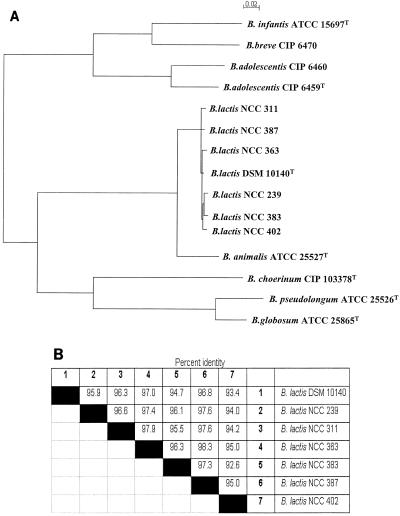

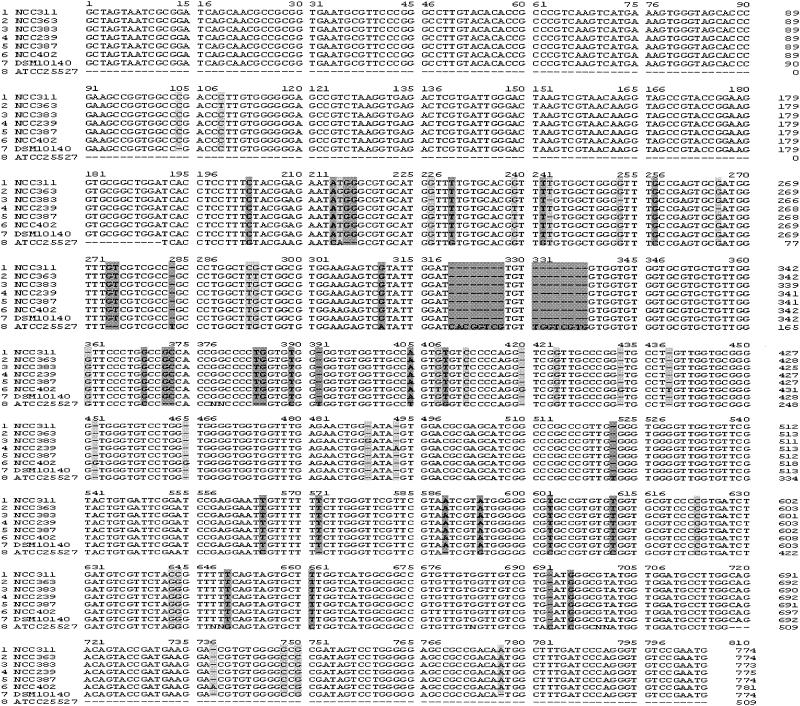

The sequences of the 16S-23S ITS regions of strains NCC 363, NCC 383, NCC 402, NCC 239, NCC 387, and NCC 311 were determined from those amplicons generated with the PCR primers 16S-for and 23Si. The complete fragments were sequenced directly and multiple times on both DNA strands. Comparison of the six spacer sequences obtained with that of B. lactis DSM 10140 already deposited in the GenBank database revealed similarity levels ranging from 93.4 to 97% (Fig. 3B). Analysis of most of the B. lactis sequences revealed some variable sites, which included base additions, deletions, or substitutions (Fig. 4). The most striking differences were observed in relation to the type strain of B. animalis, where two eight-nucleotide inserts between bp 319 and 338 were absent in the ITS of any of the B. lactis strains studied here (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

(A) Dendrogram based on 16S-23S ITS sequences and showing the relationships of members of the genus Bifidobacterium related to B. animalis and B. lactis strains. The bar at the top indicates 0.02% sequence divergence. The 16S-23S ITS sequences used to draw the phylogenetic tree of the following strains were retrieved from the GenBank database: B. infantis ATCC 15697 (accession no. U09792), B. breve CIP 6470 (accession no. U09521), B. adolescentis CIP 6460 (accession no. U09513), B. adolescentis CIP 6459 (accession no. U09512), B. lactis DSM 10140 (accession no. X89513), B. animalis ATCC 25527 (accession no. U09858), B. choerinum CIP 103378 (accession no. L36968), B. pseudolongum ATCC 25526 (accession no. U09879), and B. globosum ATCC 25865 (accession no. U09524). (B) Overall 16S-23S rRNA spacer region sequence similarities of B. lactis strains.

FIG. 4.

Multiple alignment of the ITS sequences of six B. lactis strains, B. lactis DSM 10140 (accession no. X89513), and B. animalis ATCC 25527 (accession no. U09858). Nucleotides that differ between B. lactis strains and B. animalis ATCC 25527 are shaded in dark grey. Nucleotides that differ among B. lactis strains are shaded in light grey.

The phylogenetic relationships among ITS sequences of the related species B. animalis and B. lactis (1) are described in Fig. 3A. Consistent with the results of Bourget et al. (1), our phylogenetic tree clearly shows that all of the B. lactis strains and B. animalis strain ATCC 25527 are in the same cluster, which can be further separated into two subclusters, of which one is formed by B. lactis and the other is formed by B. animalis ATCC 25527.

Notably, two insertions of eight nucleotides each were identified in B. animalis but not in B. lactis and provided a PCR target for rapid separation of these two species. The Ban2 primer was designed to anneal to this conserved B. animalis region (Fig. 5A). The reverse primer, 23Si, was derived from the sequences encompassing the 3′ end of ITS and the 5′ end of the 23S rDNA and was complementary overall to all of the ITS sequences of B. animalis and B. lactis strains. Moreover, because of an often-occurring variability of PCR conditions, the lack of any amplicons must be attributed not only to the absence of any target DNA but also to an overall failure of the amplification reaction. To distinguish between these two events, we included primers Lm3 and Lm26 (6), which target conserved regions within the 16S rDNA of the genus Bifidobacterium, in the same PCR mixtures. When a Multiplex-PCR was performed with this mixture of four primers in the same reaction mixture, two amplicons of 467 and 1,350 bp were only detectable in the presence of DNA isolated from B. animalis (the sizes of all achievable PCR amplicons were calculated from databases and estimated by gel electrophoresis). The amplification of all other Bifidobacterium DNAs produced only one amplicon of 1,350 bp. The results of these PCR assays, on the basis of the ITS sequence data, are depicted in Fig. 5B. The 467-bp amplicon that occurred was apparent for two B. animalis strains but not for any of the B. lactis strains. Furthermore, we confirmed the overall absence of PCR amplicons for all other bifidobacterial type strains (data not shown).

B. lactis identification based on molecular sequence data has been hampered so far by the lack of detectable sequence variation between closely related B. animalis strains. Genetic information derived from 16S-23S rRNA spacer regions can be used to differentiate closely related organisms (1, 17).

More recently, Cai et al. (2) showed that the DNA of B. animalis ATCC 27536 and ATCC 27674 had a high level of overall DNA relatedness with B. lactis DSM 10140, ranging from 94.2 to 94.8%, which is significantly higher than their relatedness to B. animalis ATCC 25527. Since the DNA-DNA homology between B. lactis DSM 10140 and B. animalis ATCC 25527 has already been demonstrated to be 85.5% (2) and is therefore too high to allow separation of these strains into two separate species, no decision has been made by the International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology about whether to continue to treat B. lactis as a species separate from B. animalis (14).

Roy et al. (12, 13) also reported that B. animalis ATCC 27536 has an ldh nucleotide sequence identical to that of B. lactis DSM 10140 and a PFGE pattern more similar to that of the type strain of B. lactis than to that of the type strain of B. animalis. Analysis of a 60-kDa heat shock protein (HSP60) gene showed that the DNA sequence similarity between B. lactis DSM 10140 and B. animalis ATCC 25527 is high (98%), as is that among B. infantis, B. longum, and B. suis, but lower than that between strains of the same species (5). Therefore, the high level of 16S rDNA sequence similarity of 98.6%, (8) between the B. animalis and B. lactis type strains is additional evidence that these two taxa might, in fact, be combined. Thus, our 16S-23S ITS sequence data and ERIC-PCR data are consistent with above-mentioned data and suggest that these two species might be designated two subspecies of the same species. In fact, 16S rDNA sequence analysis is a good tool with which to explore intergenic relationships, while 16S-23S rDNA spacer region comparison provides information concerning intraspecific links and allows the detection of recently divergent species, as proposed by Bourget (1). Considering the new B. lactis strains described here and comparing them with the few B. animalis strains available, we suggest the use of the names B. animalis subsp. lactis, which includes strains DSM 10140, ATCC 27536, ATCC 27674, and ATCC 27673 and the new strains reported in this study, and B. animalis subsp. animalis, which includes, e.g., strains ATCC 25527 and ATCC 27672. Notably, all of these strains exhibit individual PFGE and/or randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR, and/or triplicate arbitrary primed PCR profiles (12; unpublished results), justifying separate strain designations.

Physiologic characteristics based on their different abilities to grow on milk-based medium give additional support for a potential taxonomic separation of strains of B. lactis from strains of B. animalis. In fact, B. lactis strains and very few B. animalis strains (ATCC 27536, ATCC 27674, and ATCC 27673) are able to grow in pure milk whereas B. animalis ATCC 25527 and ATCC 27672 both grow poorly in pure milk. Potentially, for this reason, all strains found in dairy products (e.g., yoghurt and infant formula), including products purported to contain B. animalis and/or B. lactis strains, do not at all resemble B. animalis but are, in fact, only strains of the B. lactis taxon. According to Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (16), division of a species into subspecies is based on phenotypic variations (e.g., growth on milk-based medium) or on genetically determined clusters of strains within the species. On the basis of the above criterion, we suggest that B. lactis should not be considered a junior subjective synonym of B. animalis but rather be reclassified as a subspecies of B. animalis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourget, N. L., H. Philippe, I. Mangin, and B. Decaris. 1996. 16S rRNA and 16S to 23S internal transcribed spacer sequence analyses reveal inter- and intraspecific Bifidobacterium phylogeny. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:102-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai, Y., M. Matsumoto, and Y. Benno. 2000. Bifidobacterium lactis Meile et al. 1997 is a subjective synonym of Bifidobacterium animalis (Mitsuoka 1969) Scardovi and Trovatelli 1974. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:815-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun, J., A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1999. Analysis of 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer regions of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2202-2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan, A. A., I. U. Khan, A. Abdulmawjodd, and C. Lämmler. 2001. Evaluation of PCR methods for rapid identification and differentiation of Streptococcus uberis and Streptococcus parauberis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1618-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jian, W., L. Zhu, and X. Dong. 2001. New approach to phylogenetic analysis of the genus Bifidobacterium based on partial HSP60 gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1633-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufmann, P., A. Pfefferkorn, M. Teuber, and L. Meile. 1997. Identification and quantification of Bifidobacterium species isolated from food with genus-specific 16S rRNA-targeted probes by colony hybridization and PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1268-1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kok, R., A. Waal, F. Schut, G. W. Welling, G. Weenk, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 1996. Specific detection and analysis of a probiotic Bifidobacterium strain in infant feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3668-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meile, L., W. Ludwig, U. Rueger, C. Gut, P. Kaufmann, G. Dasen, S. Wenger, and M. Teuber. 1997. Bifidobacterium lactis sp. nov., a moderately oxygen tolerant species isolated from fermented milk. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20:57-64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez Luz, S., F. Rodríguez-Valera, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Variation of the ribosomal operon 16S-23S gene spacer region in representatives of Salmonella enterica subspecies. J. Bacteriol. 180:2144-2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad, J., H. Gill, J. Smart, and P. K. Gopal. 1998. Selection and characterisation of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains for use as probiotics. Int. Dairy J. 8:993-1002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogall, T., J. Wolters, T. Flohr, and E. C. Böttger. 1990. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 40:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy, D., P. Ward, and G. Champagne. 1996. Differentiation of bifidobacteria by use of pulsed field gel electrophoresis and polymerase chain reaction. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 29:11-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy, D., and S. Sirois. 2001. Molecular differentiation of Bifidobacterium species with amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis and alignment of short regions of ldh gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seventh International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology. 2001. Minutes of the meetings, 22 and 23 September 1999, Veldhoven, The Netherlands. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:259-261. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuhaimi, M., A. M. Ali, N. M. Saleh, and A. M. Yazid. 2001. Utilisation of enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) sequence-based PCR to fingerprint the genomes of Bifidobacterium isolates and other bacteria. Bio/Technol. Lett. 23:731-736. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staley, J. T., and N. R. Krieg. 1986. Classification of procaryotic organisms: an overview, p. 1-4. In P. H. A. Sneath, N. S. Mair, M. E. Sharpe, and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 1. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 17.Tannock, G. W., A. Tilsala-Timisjarvi, S. Rodtong, J. Ng, K. Munro, and T. Alatossava. 1999. Identification of Lactobacillus isolates from the gastrointestinal tract, silage, and yoghurt by 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer region sequence comparisons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4264-4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ventura, M., I. Jankovic, D. C. Walker, R. D. Pridmore, and R. Zink. 2002. Identification and characterization of novel surface proteins in Lactobacillus johnsonii and Lactobacillus gasseri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6172-6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ventura, M., M. Elli, R. Reniero, and R. Zink. 2001. Molecular microbial analysis of Bifidobacterium isolates from different environments by the species-specific amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (ARDRA). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 36:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ventura, M., R. Reniero, and R. Zink. 2001. Specific identification and targeted characterization of Bifidobacterium lactis from different environmental isolates by a combined Multiplex-PCR approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2760-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker, D. C., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1994. Isolation of a novel IS3 group insertion element and construction of an integration vector for Lactobacillus spp. J. Bacteriol. 176:5330-5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woese, C. R. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51:221-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]