Abstract

The relationship among growth temperature, membrane fatty acid composition, and pressure resistance was examined in Escherichia coli NCTC 8164. The pressure resistance of exponential-phase cells was maximal in cells grown at 10°C and decreased with increasing growth temperatures up to 45°C. By contrast, the pressure resistance of stationary-phase cells was lowest in cells grown at 10°C and increased with increasing growth temperature, reaching a maximum at 30 to 37°C before decreasing at 45°C. The proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in the membrane lipids decreased with increasing growth temperature in both exponential- and stationary-phase cells and correlated closely with the melting point of the phospholipids extracted from whole cells examined by differential scanning calorimetry. Therefore, in exponential-phase cells, pressure resistance increased with greater membrane fluidity, whereas in stationary-phase cells, there was apparently no simple relationship between membrane fluidity and pressure resistance. When exponential-phase or stationary-phase cells were pressure treated at different temperatures, resistance in both cell types increased with increasing temperatures of pressurization (between 10 and 30°C). Based on the above observations, we propose that membrane fluidity affects the pressure resistance of exponential- and stationary-phase cells in a similar way, but it is the dominant factor in exponential-phase cells whereas in stationary-phase cells, its effects are superimposed on a separate but larger effect of the physiological stationary-phase response that is itself temperature dependent.

High hydrostatic pressure is increasingly being used as a means of preserving food without loss of flavor and other desirable attributes (13). The process has now been successfully applied to a variety of products including fruit juices and purées, guacamole, sauces, desserts, rice dishes, oysters, and packaged cured ham. An understanding of the factors that affect microbial pressure resistance is obviously important in the further development of this technology.

Many microbial cell structures including ribosomes, enzymes, the nucleoid, and the cell membrane are affected by high hydrostatic pressure (9, 40). The mechanisms of inactivation are still not completely understood, although it is generally acknowledged that membrane damage seems to play an important role in loss of viability. Loss of the physical integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane has been demonstrated as leakage of ATP or UV-absorbing material from bacterial cells subjected to pressure (38) or as increased uptake of fluorescent dyes such as propidium iodide that are normally excluded by the membranes of intact cells (5, 32). Loss of some functions associated with the cytoplasmic membrane as a result of pressurization has also been described. In Lactobacillus plantarum, loss of activity of the F0F1 ATPase and the multidrug transporter HorA are believed to contribute to high-pressure inactivation (41, 45). The barrier functions of the gram-negative outer membrane may also be disrupted by pressure. This has been shown as a transient increase in permeability to nisin, lysozyme, and 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine (14, 16, 44) and by an increased sensitivity of surviving cells to bile salts (10). Membrane damage has also been implicated in lethal and sublethal injury to yeasts exposed to pressure treatments (33).

High pressure causes tighter packing of the acyl chains within the phospholipid bilayer of membranes and promotes membrane lipid gelation (24). Membrane proteins may also be displaced from the membrane, possibly as a result of these phase changes (35). Thus, it is possible that the composition and state of the bacterial cell membrane prior to pressure treatment may affect the extent of the physical changes that occur under pressure and hence cellular resistance to inactivation. In preliminary work by M. A. Casadei and B. M. Mackey, it was reported that exponential cells of Escherichia coli grown at low temperature were more resistant to high pressure than those grown at high temperatures (7). Since microbial cells increase the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) in their membranes in response to a decrease in growth temperature, this suggested a possible link between membrane fluidity and pressure resistance. The aim of the present work was to investigate the relationship among growth temperature, membrane fatty acid composition, and pressure resistance in exponential- and stationary-phase cells. Comparison of the pressure resistance of cells grown at different temperatures and hence having membranes of different fatty acid composition was done at the same treatment temperature, and cells with the same membrane composition were compared at different treatment temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth procedures.

E. coli NCTC 8164 was grown in tryptone soya broth (TSB; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) incubated in shake flasks at the temperatures specified below. Cultures were inoculated (0.1% vol/vol) with stationary-phase cells that had been incubated for approximately 18 h at 37°C. Exponential-phase cultures were grown to an optical density at 680 nm of 0.2, and stationary-phase cultures were incubated for at least 18 h after inoculation.

Viable counts.

Cell suspensions were serially diluted in maximum recovery diluent and plated in duplicate onto tryptone soya agar (Oxoid). Colonies were counted after the plates had been incubated at 37°C for 48 h. All experiments were carried out at least twice. Curves were fitted to survival data by using the DMfit curve-fitting program (available at http://www.ifr.bbsrc.ac.uk/Safety/DMFit) based on the mathematical model of Baranyi and Roberts (3).

High-pressure treatment.

Volumes of whole culture (1.5 ml) were dispensed into plastic pouches (2.5 by 2.5 cm) cut from stomacher bags (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, United Kingdom) which were then heat sealed. These were pressure treated in a Foodlab plunger press apparatus (Stansted Fluid Power, Stansted, Essex, United Kingdom) with a pressure-transmitting fluid composed of ethanol and castor oil (80:20, vol/vol). Unless stated otherwise, all pressure treatments were carried out at ambient temperature (ca. 20°C). During pressurization, a transient increase in temperature caused by adiabatic heating occurred. The maximum temperature in the transmission fluid during treatment was approximately 46°C at 600 MPa, with the time spent above 40°C during compression being 70 s. When samples were pressurized at temperatures other than ambient, temperature control was achieved using a water jacket connected to a circulating water bath.

Fatty acid extraction and analysis.

Cultures were grown to exponential or stationary phase at (10 ± 1)°C, (20 ± 1)°C, (30 ± 1)°C, (37 ± 1)°C, and (45 ± 1)°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and freeze dried. Samples were sent to Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany), where membrane fatty acids were extracted, transesterified, and analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography.

DSC.

Lipids were extracted from stationary-phase cells by using a method modified from that of Bligh and Dyer (6). Cells from 500 ml of culture were harvested by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C and washed twice in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 10 mM MgCl2. The pellets were suspended in 7 ml of the same buffer, and 20 ml of methanol and 10 ml of chloroform were added. After stirring continuously for 30 min, 10 ml of chloroform and 10 ml of buffer were added and the mixture was stirred continuously for an additional 2 h. After this time, the mixture was allowed to separate into two phases. The lower chloroform layer was filtered through a phase separator filter (1 PS; Whatman Ltd., Kent, United Kingdom), and the chloroform was allowed to evaporate. Lipid samples were hydrated by dispersing 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 10 mM MgCl2 in a ratio of approximately 1 mg to 10 μl and sonicating for 3 min. Samples (20 μl) were added to differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) sample pans, which were sealed and held at −20°C for 30 min before transfer to a Perkin-Elmer DSC 7 calorimeter. DSC analysis was carried out using a temperature gradient from −10 to 60°C and a heating rate of 10°C min−1. An empty pan was used as the reference.

RESULTS

Growth temperature and pressure resistance.

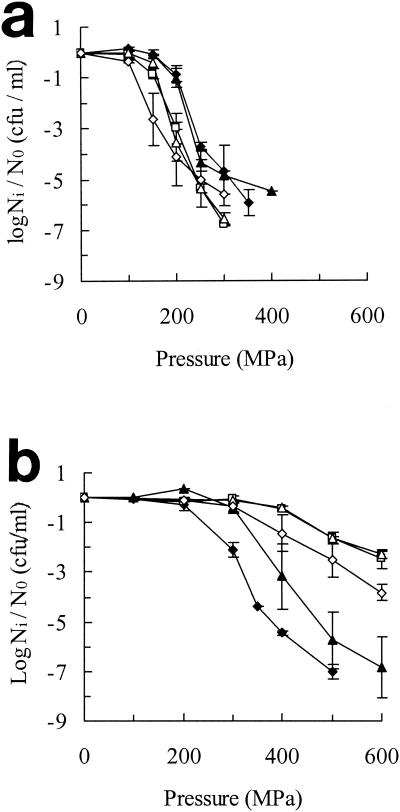

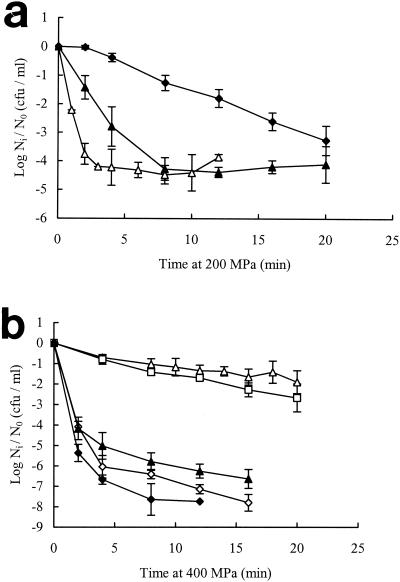

The effect of growth temperature on pressure resistance of Escherichia coli NCTC 8164 is shown in Fig. 1. Pressure resistance was assessed by comparison of survival levels after exposure of cells to a range of pressures for a fixed time (5 min). The pressure resistance of exponential-phase cells was maximal in cells grown at 10°C and decreased slightly but continuously with increasing growth temperatures up to 45°C (Fig. 1a). By contrast, the pressure resistance of stationary-phase cells was lowest in cells grown at 10°C and increased with increasing growth temperature, reaching a maximum at 30 to 37°C and then decreasing at 45°C (Fig. 1b). Resistance to high pressure was also assessed by comparing the rates of inactivation at a single pressure (Fig. 2). The kinetics of inactivation were often nonlinear, but inspection of the initial rates confirmed the previous conclusion that the effect of growth temperature on pressure resistance in stationary-phase cells differed from that in exponential-phase cells.

FIG. 1.

Effect of growth temperature on pressure resistance of E. coli NCTC 8164. Cells were grown in TSB at 45°C (⋄), 37°C (▵), 30°C (□), 20°C (▴), or 10°C (♦) to exponential phase (a) or stationary phase (b) and treated for 5 min at different pressures. Ni, number of cells after treatment; N0, initial number of cells. Results are means of at least two observations ± standard deviation (error bars).

FIG. 2.

Effect of growth temperature on pressure resistance of E. coli NCTC 8164. Cells were grown in TSB at different temperatures to exponential (a) or stationary (b) phase and treated at 200 and 400 MPa, respectively. Growth temperatures were as follows: 45°C (⋄), 37°C (▵), 30°C (□), 20°C (▴), and 10°C (♦). Ni, number of cells after treatment; N0, initial number of cells. Results are means of at least two observations ± standard deviation (error bars).

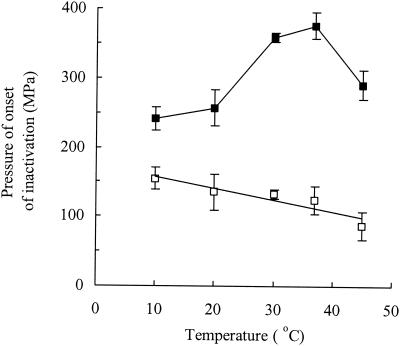

To provide an objective measure of pressure resistance, the pressures at onset of cell death (Ponset, being the length of the “shoulders” on the curves shown in Fig. 1) were calculated using the Baranyi curve-fitting program (see Materials and Methods). The use of this parameter allowed the effects of growth temperature on the pressure resistance of exponential- and stationary-phase cells to be compared directly over the whole pressure range (Fig. 3). This showed that stationary-phase cells were more resistant than exponential-phase cells at all growth temperatures, but the difference varied widely, being greatest at 30 to 37°C and least at 10°C. Figure 3 also shows that growth temperature had a greater effect on pressure resistance in stationary-phase cells than in exponential-phase cells. The relationship between growth temperature and pressure resistance for exponential-phase cells was given by the following equation: Ponset = −1.66 · Tg + 173 (R2 = 0.85), where Tg is the growth temperature.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the pressure resistance of exponential-phase (□) and stationary-phase (▪) cells grown at different temperatures. Pressure resistance is expressed as the pressure at onset of cell death (±standard error), which was calculated from data shown in Fig. 1 by using the DMFit program (see Materials and Methods).

Growth temperature and membrane composition.

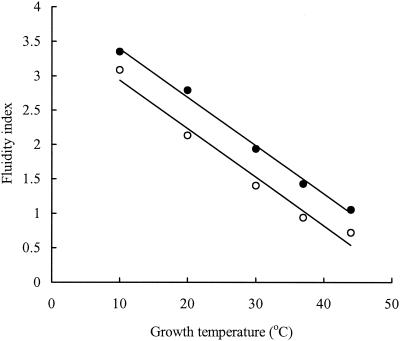

In both exponential- and stationary-phase cells, the proportion of saturated fatty acids (SFA) in the membrane increased with increasing growth temperature while the proportion of UFA decreased (Tables 1 and 2). In stationary phase, the amounts of C18:1 and C16:1 SFA decreased while the amounts of cyclopropane fatty acids (CFA) increased. Maximum levels of CFA in stationary-phase cells were seen at 30°C. The fluidity index (FI) was calculated as the ratio of UFA (plus CFA, in stationary phase) to SFA. The shorter-chain fatty acids were excluded in the calculation of the index since these fatty acids are found principally in the lipid A component of the outer membrane and therefore do not contribute substantially to the fluidity of the cytoplasmic membrane. The FI was inversely proportional to growth temperature in both exponential- and stationary-phase cells, though exponential-phase cells had slightly higher FI values than stationary-phase cells (Fig. 4). The FI values were determined by the following equations: FI = −0.0687 · Tg + 4.06 (R2 = 0.99) (for exponential-phase cells) and FI = −0.0689·Tg + 3.60 (R2 = 0.97) (for stationary-phase cells), where Tg is the growth temperature.

TABLE 1.

Fatty acid composition of exponential-phase cells of E. coli NCTC 8164 grown at different temperatures

| Fatty acid(s) | % of total composition at growth temp (°C) of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 37 | 45 | |

| 12:0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 3.9 |

| 14:0 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.9 |

| 15:0 | 0.3 | ||||

| 14:0-3OH | 6.4 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 8.9 |

| 16:1 ω7c | 28.3 | 32.3 | 27.9 | 25.5 | 26.4 |

| 16:1 ω5c | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||

| 16:0 | 19.0 | 21.9 | 27.0 | 31.2 | 37.5 |

| 17:0 cyclo | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| 17:0 | 0.2 | ||||

| 18:2 ω6, 9c | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||

| 18:1 ω9c | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 18:1 ω7c | 38.2 | 29.5 | 25.5 | 19.4 | 13.2 |

| 18:1 ω6c | |||||

| 18:0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| UFAa | 67.1 | 62.7 | 53.9 | 46.0 | 40.1 |

| SFAb | 20.0 | 22.5 | 27.9 | 32.4 | 38.3 |

| CFA | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| FIc | 3.4 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| SCFAd | 12.6 | 14.4 | 17.7 | 20.9 | 20.5 |

16:1 and 18:1.

16:0 and 18:0.

(UFA + CFA)/SFA.

SCFA, short-chain fatty acids (12:0, 14:0, and β14-OH).

TABLE 2.

Fatty acid composition of stationary-phase cells of E. coli NCTC 8164 grown at different temperatures

| Fatty acid(s) | % of total composition at growth temp (°C) of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 37 | 45 | |

| 12:0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| 13:0 | 0.4 | ||||

| 14:0 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 11.8 |

| 13:0-3OH | 0.4 | ||||

| 15:0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 14:0-3OH | 8.0 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 8.3 |

| 16:1 ω9c | 0.4 | 0.2 | |||

| 16:1 ω7c | 21.8 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.8 |

| 16:1 ω5c | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||

| 16:0 | 20.2 | 25.4 | 34.6 | 38.5 | 42.7 |

| 17:1 ω7c | 0.2 | ||||

| 17:0 cyclo | 6.0 | 24.2 | 29.4 | 22.1 | 19.1 |

| 17:0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |||

| 18:1 ω7c | 34.2 | 12.0 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| 18:1 ω6c | 0.1 | ||||

| 18:0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | |

| 18:1 ω7c 11 methyl | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||

| 19:0 iso | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | ||

| 19:0 cyclo | 0.6 | 13.5 | 12.7 | 10.4 | 7.0 |

| UFAa | 57.2 | 17.1 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 5.1 |

| SFAb | 20.7 | 25.7 | 34.6 | 38.9 | 43.4 |

| CFA | 6.6 | 37.6 | 42.1 | 32.5 | 26.0 |

| FIc | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| SCFAd | 15.6 | 19.2 | 17.1 | 24.6 | 25.2 |

16:1 and 18:1.

16:0 and 18:0.

(UFA + CFA)/SFA.

SCFA, short-chain fatty acids (12:0, 14:0, and β14-OH).

FIG. 4.

Effect of growth temperature on the membrane FI of exponential-phase (•) and stationary-phase (○) cells.

Membrane fluidity and pressure resistance.

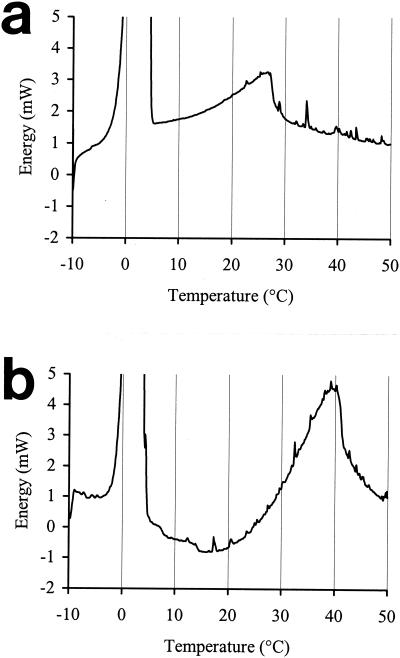

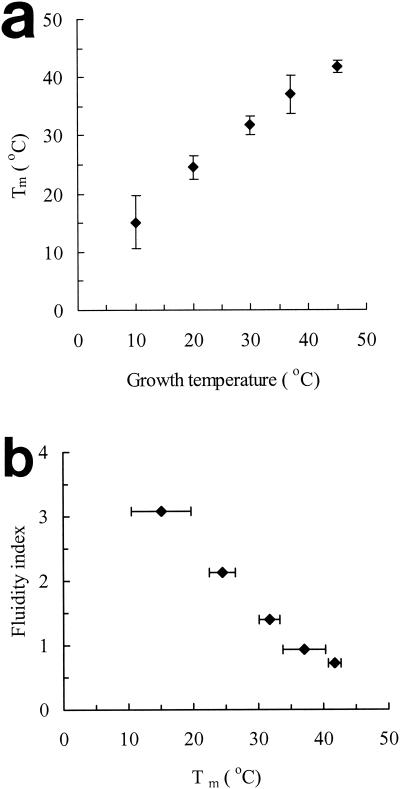

To assess the relationship among growth temperature, the FI, and the melting behavior of membrane lipids, total phospholipids were extracted from stationary-phase cells grown at different temperatures and analyzed by DSC. This technique measures the release or absorption of energy occurring when the physical state of the sample changes. The resulting thermograms showed a single broad asymmetric peak (apart from the large endotherm associated with the melting of ice) (Fig. 5). The position of the peak maximum (Tm) on the temperature axis indicates the temperature at which the excess specific heat absorbed by the system is at a maximum. For symmetrical peaks, this corresponds to the phase transition temperature at which 50% of the lipids are in the liquid crystalline state. The area underneath the peaks corresponds to the energy absorbed during melting, and its magnitude is affected by the number of molecules involved in the change of state and by their homogeneity and hydration level. The Tm was directly related to the growth temperature (Fig. 6a) and inversely related to the FI (Fig. 6b).

FIG. 5.

DSC heating profiles for aqueous suspensions of lipids extracted from whole cells of E. coli NCTC 8164 grown in TSB to stationary phase at 20°C (a) and 37°C (b).

FIG. 6.

Relationships between growth temperature and phase transition temperature (Tm) (a) and between Tm and FI (b) of phospholipids extracted from whole stationary-phase cells (error bars indicate standard deviation).

On the assumption that membrane fluidity at a fixed temperature is directly related to the melting point of the phospholipids (i.e., the lower the melting point, the more fluid the membrane), we may conclude that, for exponential-phase cells, a more fluid membrane was correlated with increased pressure resistance. In stationary-phase cells, an unexpected and more complex picture emerged. At growth temperatures between 10 and 37°C, the relationship between membrane fluidity and pressure resistance was apparently the opposite of that seen in exponential-phase cells, i.e., cells with more-rigid membranes were more pressure resistant. In cells grown at 45°C, this trend was reversed, i.e., membrane rigidity increased and pressure resistance decreased, compared with cells grown at 37°C.

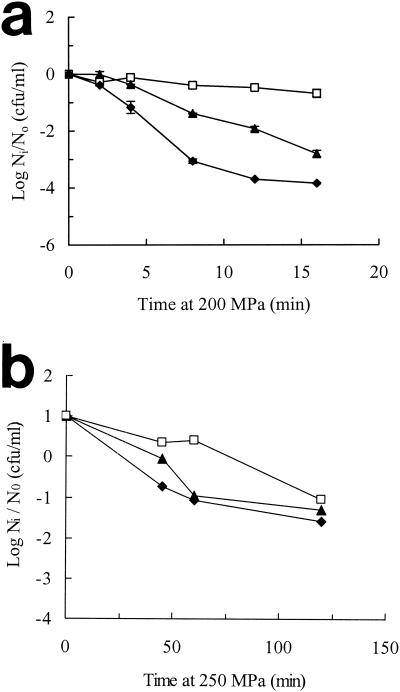

We further examined the relationship between membrane fluidity and pressure resistance of exponential- and stationary-phase cells by varying the temperature of pressure treatment, on the assumption that membrane fluidity during pressure treatment would tend to increase with increasing ambient temperature. The growth temperatures were chosen to produce cells with large differences in membrane fatty acid composition, i.e., 10°C for exponential-phase cells and 37°C for stationary-phase cells. As shown in Fig. 7, pressure resistance in both exponential- and stationary-phase cells increased with increasing temperatures of pressure treatment (between 10 and ca. 30°C), although the effect was much more clear-cut in exponential-phase cells.

FIG. 7.

Effect of temperature of pressurization on pressure resistance of E. coli NCTC 8164. (a) Exponential-phase cells were grown at 10°C in TSB and pressure treated at 10°C (♦), 20°C (▴), or 30°C (□). (b) Stationary-phase cells were grown at 37°C and pressure treated at 10°C (♦), 22°C (▴), or 29°C (□). Ni, number of cells after pressure treatment; N0, initial number of cells.

DISCUSSION

Growth temperature and membrane fatty acid composition.

As expected, growth of E. coli NCTC 8164 at different temperatures resulted in differences in membrane fatty acid composition. In both exponential- and stationary-phase cells, the proportion of UFA increased with decreasing temperatures while the opposite was true for SFA. This finding is similar to results previously reported by others (18, 19, 27, 29, 39). The melting point of UFA is lower than that of SFA, and the general effect of the incorporation of more UFA in the membrane is a decrease in the phase transition temperature (2). Changing the composition of the cell membrane in response to growth temperature thus serves the purpose of maintaining a degree of fluidity, which is compatible with life (19).

The ratio of UFA to SFA has been used as an indirect indicator of membrane fluidity (11). We verified the correspondence among growth temperature, the FI, and the physical behavior of the membrane by measuring the phase transition temperature of the phospholipid mixture extracted from whole cells by use of DSC. The main peak temperature was linearly related to the growth temperature and to the FI, confirming the homeoviscous response of the cells to different growth temperatures and also the validity of this index as an indication of membrane fluidity.

The disagreement in the earlier literature on the phase transition temperature of the lipids of wild-type E. coli was probably related to the measurement techniques employed and the methods of preparing the membranes or lipids (19, 37, 43). The calorimetric studies of Jackson and Cronan (19) showed that the phase transition of membrane phospholipids of E. coli was completed below the temperature of growth, whereas we found that the midpoint of membrane lipid melting occurred around the growth temperature. We used a much faster scanning rate, which would result in a higher Tm value, and this may partly explain the different results. It is also possible that despite sonication in buffer, the phospholipids in our preparations were not fully hydrated, which would also have increased their melting temperature. Nevertheless, our DSC results clearly showed that the phase transition temperature of membrane phospholipids in E. coli NCTC 8164 increased linearly with temperature. This is consistent with the observations of Mejía et al. (30), who showed that the membrane fluidity of E. coli W3110, as measured by excimerization of dipyrenylpropane, decreased linearly with growth temperature.

Growth temperature and pressure resistance.

Exponential- and stationary-phase cells showed unexpected differences in the way that growth temperature affected pressure resistance. In exponential-phase cells, pressure resistance decreased as growth temperature increased, whereas in stationary-phase cells, pressure resistance increased to a maximum at 30 to 37°C and then declined. The decrease in pressure resistance of exponential-phase cells that occurred with increasing growth temperature is in agreement with the observations of Smelt et al. (41) and ter Steeg et al. (44), who showed that exponential-phase cells of Lactobacillus plantarum grown at 10°C were more pressure resistant than those grown at 30°C.

The complex behavior of stationary-phase cells reported here has not been described previously, but Lanciotti et al. (21) reported that cells of Listeria monocytogenes and Yarrowia lipolytica treated at the end of exponential phase were more resistant to high-pressure homogenization when grown at lower temperatures. In contrast, E. coli was more resistant to homogenization when grown at higher temperatures, having an optimum growth temperature for pressure resistance of above 20°C. Recently McClements et al. (28) found that the pressure resistance of exponential-phase cells of several psychrotrophic bacteria was less when the cells were grown at 30°C than when they were grown at 8°C, whereas the reverse was true of stationary-phase cells; in addition, Ulmer et al. (45) reported that stationary-phase cells of L. plantarum grown at 15°C were slightly less resistant than those grown at 37°C. However, there have been no previous reports comparing the effects of growth temperatures over a wide range in both exponential- and stationary-phase cells.

It is well known that stationary-phase cells are more pressure resistant than exponential-phase cells (5, 25). Our results are in agreement with this but showed for the first time that the difference in pressure resistance between exponential- and stationary-phase cells varies widely depending on growth temperature. At the optimum growth temperature for E. coli of 37°C, the differences were large, whereas in cells grown at 10°C, the differences were small. This may be because the protective stationary-phase responses are not induced to the same extent in cells grown at 10°C.

Interpretation of the interrelationships among growth temperature, growth phase, and temperature of pressurization.

Based on the results presented here and those previously reported by others, we propose the following interpretation of the effect of the interrelationships among growth temperature, growth phase, treatment temperature, and membrane fluidity on microbial pressure resistance. With regard to the effect of temperature during treatment, many authors have reported a broad optimum temperature for resistance between approximately 20 to 30°C (9, 23, 42). Our results showing that resistance of E. coli NCTC 8164 decreases between 30 and 10°C are consistent with this previous finding. We propose that differences in resistance below the optimum temperature are caused mainly by differences in membrane fluidity, with lower treatment temperatures causing a stiffening of the membrane and consequent loss of pressure resistance (at higher treatment temperatures above the optimum, cellular inactivation may be a more complex process in which cell structures additional to the membrane are involved). With regard to temperatures below the optimum, we suggest that treatment temperature affects membrane fluidity and pressure resistance in exponential- and stationary-phase cells in a similar way. In the case of exponential-phase cells, we believe that membrane fluidity is the dominant factor affecting pressure resistance, so resistance increases under all conditions where the membrane is more fluid, i.e., with decreasing growth temperature and with increasing treatment temperature (up to the optimum). However, in the case of stationary-phase cells, we believe that membrane fluidity contributes to resistance but is not the dominant factor. We suggest instead that the physiological changes that occur as cells enter the stationary phase have an overriding effect on pressure resistance that is independent of membrane fluidity. Thus, in stationary-phase cells, treatment temperature affects resistance in a manner similar to its effect on exponential-phase cells but this effect is superimposed on the independent but much larger effects of stationary-phase adaptation (discussed below) that are expressed most strongly in cells grown at 30 to 37°C (Fig. 3).

Membrane fluidity and pressure resistance.

The effect of membrane fluidity on pressure resistance has been examined previously by using a fatty acid auxotroph of E. coli in which membrane composition can be altered independently of temperature (8). In exponential-phase cells grown at 37°C, pressure resistance was lower in cells grown on elaidic acid than in cells grown on oleic or linoleic acid, confirming that pressure resistance increases with increasing membrane fluidity. In stationary-phase cells, differences in resistance were small and more difficult to interpret. During the initial phase of inactivation, cells grown on elaidic acid were the most sensitive, as was the case with exponential-phase cells, but showed more survivors in the tail region of the curve. These results support the hypothesis that fluidity has a greater effect in determining the resistance of exponential-phase cells than that of stationary-phase cells. It is worth noting that membrane fluidity affects cellular heat resistance in a manner that is opposite to its effect on pressure resistance, i.e., cells with more-fluid membranes are more heat sensitive (12, 15, 20).

The reason why more-fluid membranes are less susceptible to pressure damage is not immediately obvious. Pressure causes closer packing of the hydrocarbon chains of phospholipids and in this sense has an effect similar to cooling. The pressure at which a phase transition occurs would be higher in cells with more-fluid membranes, but we do not know whether this would affect the nature of the phase transition and hence the damaging effects on the membrane. Passing through a membrane phase transition caused by a decrease in temperature is not necessarily lethal, but death can result if exponential-phase, but not stationary-phase, cells are chilled very rapidly (26). In this case, it is believed that rapid cooling prevents the lateral phase separation of phospholipid and protein domains that occurs during slow cooling, and this leads to the formation of grain boundaries and packing faults in the gelled membrane and leakage of cell components (22). Recently, Ulmer et al. (45) examined the relationship between pressure inactivation of stationary-phase cells of L. plantarum and inactivation of the multidrug transporter HorA. By measuring phase transitions during pressure treatment or thermal shifts, they were able to show that temperature-induced phase transitions were reversible and did not affect HorA activity or viability, whereas pressure-induced phase transitions caused loss of HorA activity and viability. Their conclusion that cells with liquid crystalline membranes at ambient pressure (0.1 MPa) are more sensitive to pressure than those with membranes in the gel phase differs from the generally accepted view (36, 41).

Several other studies have demonstrated an effect of membrane fluidity on enzyme activity. For example, an inverse relationship exists between membrane ATPase activity and the molecular order of the surrounding membrane (24). These effects on activity are reversible, but irreversible inactivation of ATPase was suggested as a contributory cause of cell death in L. plantarum (41, 46). Pressure may be envisioned to have an irreversible effect on membrane proteins in one of two ways: either the proteins could be denatured in situ or they might be squeezed out of the membrane as a result of closer packing of membrane phospholipids. Ritz et al. (35) showed that pressures of 350 MPa and above cause substantial loss of protein from both cytoplasmic and outer membranes. It would be of obvious interest to examine whether displacement of proteins was affected by the initial fluidity of the membrane.

Stationary-phase adaptation and pressure resistance.

Despite the contribution of membrane fluidity to pressure resistance, it appears that more-fundamental changes affecting resistance occur during entry to stationary phase. In most bacterial species characterized to date, entry into the stationary phase or starvation is accompanied by profound structural and physiological changes that result in increased resistance to heat shock and oxidative, osmotic, and acid stresses. In E. coli, these changes result from the expression of over 50 genes, most of which are regulated by the alternative sigma factor RpoS (σs), but other regulatory elements such as the universal stress protein UspA are also involved (17). The importance of RpoS in the development of pressure resistance in E. coli O157 was shown by Robey et al. (34). It is not clear which particular adaptations are important, but the acquisition of a more resilient cell envelope appears to be critical, because the cytoplasmic membranes of stationary-phase cells are much less susceptible to disruption by pressure than those of exponential-phase cells and the resistance of the stationary-phase membrane to pressure-induced permeabilization was related to rpoS status (5, 32).

Beney et al. (4) used microscopy to examine the effect of pressure on vesicles composed of egg yolk phosphatidylcholine. During compression, vesicles decreased in volume while remaining spherical, but during decompression, membrane material was lost by budding. The inclusion of cholesterol suppressed the initial volume decrease and prevented loss of material during decompression. If pressure causes similar physical effects on bacterial membranes, then it is likely that membrane composition would affect the process and might therefore affect pressure resistance. Cholesterol is not found in E. coli, but other factors might affect membrane responses to pressure. Several changes in the membrane and cell envelope occur on entry to stationary phase, including the conversion of UFA to their cyclopropane derivatives, a thickening of the peptidoglycan layer, an increase in peptide-lipoprotein cross-linking, and cross-linking of membrane proteins (17). The membrane content of CFA and pressure resistance were both maximal in cells grown at approximately 30 to 37°C (Table 2), suggesting that CFA could play a role in pressure resistance during stationary phase. However, other changes not necessarily related to envelope composition may also affect pressure resistance, so further work is needed to clarify this. For example, stabilization of ribosomes occurs in stationary phase (1) and denaturation of ribosomes has been correlated with cell death in pressure-treated stationary-phase cells of E. coli NCTC 8164 (31).

The relationship between membrane damage and loss of viability following pressure treatment has previously been examined in strains of E. coli O157 that had inherent differences in their resistance to pressure (5, 32). In exponential-phase cells, loss of viability was correlated with a permanent loss of membrane integrity in all strains, whereas in stationary-phase cells, a more complicated picture emerged in which cell membranes became leaky during pressure treatment but resealed to a greater or lesser extent following decompression. The present study confirms the view that the membrane is a critical target in pressure inactivation but also suggests that there are fundamental differences in the role of the cell membrane in determining the pressure resistance of exponential- and stationary-phase cells.

Acknowledgments

M. A. Casadei was supported by a Research Studentship provided by the United Kingdom Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. P. Mañas was the recipient of a Marie Curie Individual Fellowship from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apirakaramwong, A., J. Fukuchi. K. Kashiwagi, Y. Kakinuma, E. Ito, A. Ishihama, and K. Igarashi. 1998. Enhancement of cell death due to decrease in Mg2+ uptake by OmpC (cation-selective porin) deficiency in ribosome modulation factor-deficient mutant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251:482-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldassare, J. J., K. B. Rhinehart, and D. F. Silbert. 1976. Modification of membrane lipid: physical properties in relation to fatty acid structure. Biochemistry 15:2986-2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranyi, J., and T. A. Roberts. 1994. A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial growth in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 23:277-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beney, L., J. Perrier-Cornet, M. Hayert, and P. Gervais. 1997. Shape modification of phospholipid vesicles induced by high pressure: influence of bilayer compressibility. Biophys. J. 72:1258-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benito, A., G. Ventoura, M. A. Casadei, T. P. Robinson, and B. M. Mackey. 1999. Variation in resistance of natural isolates of Escherichia coli O157 to high hydrostatic pressure, mild heat, and other stresses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1564-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bligh, E. G., and W. J. Dyer. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadei, M. A., and B. M. Mackey. 1997. The effect of growth temperature on pressure resistance of Escherichia coli, p. 281-282. In K. Heremans (ed.), High pressure research in the biosciences and bio/technology. Proceedings of the XXXIVth Meeting of the European High Pressure Research Group, Leuven, Belgium. Leuven University Press, Leuven, Belgium.

- 8.Casadei, M. A., and B. M. Mackey. 1999. Use of a fatty acid auxotroph to study the role of membrane fatty acid composition on the pressure resistance of Escherichia coli, p. 51-54. In H. Ludwig (ed.), Advances in high pressure bioscience and biotechnology. Proceedings of the International Conference on High Pressure Bioscience and Technology, Heidelberg, 1998. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 9.Cheftel, J. 1995. Review: high-pressure, microbial inactivation and food preservation. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 1:75-90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chilton, P., N. S. Isaacs, P. Mañas, and B. M. Mackey. 2001. Metabolic requirements for the repair of pressure-induced damage to the outer and cytoplasmic membranes of Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 71:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLong, E. F., and A. A. Yayanos. 1985. Adaptation of the membrane lipids of a deep-sea bacterium to changes in hydrostatic pressure. Science 228:1101-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis, W. H., and M. B. Yatvin. 1981. Correlation of hyperthermic sensitivity and membrane microviscosity in E. coli K1060. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 39:265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farkas, D. F., and D. G. Hoover. 2000. High pressure processing. J. Food Sci. Suppl. 47-64.

- 14.Gänzle, M. G., and R. F. Vogel. 2001. On-line fluorescence determination of pressure-mediated outer membrane damage in Escherichia coli. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24:477-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen, E. W. 1971. Correlation of fatty acid composition with thermal resistance of E. coli. Dan. Tidsskr. Farm. 45:339-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauben, K. J. A., E. Y. Wuytack, C. C. F. Soontjens, and C. W. Michiels. 1996. High-pressure transient sensitization of Escherichia coli to lysozyme and nisin by disruption of outer-membrane permeability. J. Food Prot. 59:350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huisman, G. W., D. A. Siegele, M. M. Zambrano, and R. Kolter. 1996. Morphological and physiological changes during stationary phase, p. 1672-1682. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Ingram, L. O. 1982. Regulation of fatty acid composition in Escherichia coli: a proposed common mechanism for changes induced by ethanol, chaotropic agents, and a reduction of growth temperature. J. Bacteriol. 149:166-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson, M. B., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1978. An estimate of the minimum amount of fluid lipid required for the growth of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 512:472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsui, N., T. Tsuchido, M. Takano, and I. Shibasaki. 1981. Effect of preincubation temperature on the heat resistance of Escherichia coli having different fatty acid compositions. J. Gen. Microbiol. 122:357-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanciotti, R., F. Gardini, M. Sinigaglia, and M. E. Guerzoni. 1996. Effects of growth conditions on the resistance of some pathogenic and spoilage species to high pressure homogenization. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 22:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leder, I. G. 1972. Interrelated effects of cold shock and osmotic pressure on the permeability of the membrane to permease accumulated substrates. J. Bacteriol. 111:211-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig, H., W. Scigalla, and B. Sojka. 1996. Pressure- and temperature-induced inactivation of microorganisms, p. 346-363. In J. L. Markley, D. B. Northrup, and C. A. Royer (ed.), High pressure effects in molecular biophysics and enzymology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

- 24.MacDonald, A. G. 1984. The effects of pressure on the molecular structure and physiological functions of cell membranes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 304:47-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackey, B. M., K. Forestiere, and N. Isaacs. 1995. Factors affecting the resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to high hydrostatic pressure. Food Biotechnol. 9:1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macleod, R. A., and P. H. Calcott. 1976. Cold shock and freezing damage to microbes. p. 81-109. In T. R. G. Gray and J. R. Postgate (ed.), The survival of vegetative microbes. Twenty-sixth Symposium of the Society for General Microbiology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 27.Marr, A. G., and J. L. Ingraham. 1964. Effect of temperature on the composition of fatty acids in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 84:1260-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McClements, J. M. J., M. F. Patterson, and M. Linton. 2001. The effect of growth stage and growth temperature on high hydrostatic pressure inactivation of some psychrotrophic bacteria in milk. J. Food Prot. 64:514-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGarrity, J. T., and B. Armstrong. 1981. The effect of temperature and other growth conditions on the fatty acid composition of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 27:835-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mejía, R., M. C. Gómez-Eichelmann, and M. S. Fernández. 1999. Escherichia coli membrane fluidity as detected by excimerization of dipyrenylpropane: sensitivity to the bacterial fatty acid profile. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 368:156-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niven, G. W., C. A. Miles, and B. M. Mackey. 1999. The effect of hydrostatic pressure on ribosome conformation in Escherichia coli: an in vivo study using differential scanning calorimetry. Microbiology 145:419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagán, R., and B. M. Mackey. 2000. Relationship between membrane damage and cell death in pressure-treated Escherichia coli cells: differences between exponential- and stationary-phase cells and variation among strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2829-2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrier-Cornet, J., M. Hayert, and P. Gervais. 1999. Yeast cell mortality related to a high-pressure shift: occurrence of cell membrane permeabilization. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robey, M., A. Benito, R. H. Hutson, C. Pascual, S. F. Park, and B. M. Mackey. 2001. Variation in resistance to high hydrostatic pressure and rpoS heterogeneity in natural isolates of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4901-4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritz, M., M. Freulet, N. Orange, and M. Federighi. 2000. Effects of high pressure on membrane proteins of Salmonella typhimurium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell, N. J., R. I. Evans, P. F. ter Steeg, J. Hellemons, A. Verhuel, and T. Abee. 1995. Membranes as a target for stress adaptation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 28:255-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schechter, E., T. Gulik-Krywicki, and H. R. Kaback. 1972. Correlations between fluorescence X-ray diffraction and physiological properties in cytoplasmic membranes isolated from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 274:466-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shigehisa, T., T. Ohmori, A. Saito, S. Taji, and R. Hayashi. 1991. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on characteristics of pork slurries and inactivation of microorganisms associated with meat products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 12:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinensky, M. 1974. Homeoviscous adaptation—a homeostatic process that regulates the viscosity of membrane lipids in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:522-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smelt, J. P. P. M. 1998. Recent advances in the microbiology of high pressure processing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 9:152-158. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smelt, J. P. P. M., A. G. F. Rijke, and A. Hayhurst. 1994. Possible mechanism of high-pressure inactivation of microorganisms. High Pressure Res. 12:199-203. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonoike, K., T. Setoyama, Y. Kuma, and S. Kobayashi. 1992. Effect of pressure and temperature on the death rate of Lactobacillus casei and Escherichia coli, p. 297-301. In C. Balny, R. Hayashi, K. Heremans, and P. Masson (ed.), High pressure and biotechnology, vol. 224. Colloque INSERM/John Libbey Eurotext Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 43.Steim, J. M. 1972. Membrane transitions: some aspects of structure and function, p. 183-196. In S. C. van den Berg, P. Borst, L. L. M. van Deenen, J. C. Kiermersma, E. C. Slater, and J. M. Tager (ed.), Mitochondria and biomembranes. North-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 44.ter Steeg, P. F., J. C. Hellemons, and A. E. Kok. 1999. Synergistic actions of nisin, sublethal high pressure, and reduced temperature on bacteria and yeast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4148-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ulmer, H. M., H. Herberhold, S. Fahsel, M. G. Gänzle, R. Winter, and R. F. Vogel. 2002. Effects of pressure-induced membrane phase transitions on inactivation of HorA, an ATP-dependent multidrug resistance transporter, in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1088-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wouters, P. C., E. Galaasker, and J. P. P. M. Smelt. 1998. Effects of high pressure on inactivation kinetics and events related to proton efflux in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:509-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]