Abstract

We have identified and sequenced the genes encoding the aggregation-promoting factor (APF) protein from six different strains of Lactobacillus johnsonii and Lactobacillus gasseri. Both species harbor two apf genes, apf1 and apf2, which are in the same orientation and encode proteins of 257 to 326 amino acids. Multiple alignments of the deduced amino acid sequences of these apf genes demonstrate a very strong sequence conservation of all of the genes with the exception of their central regions. Northern blot analysis showed that both genes are transcribed, reaching their maximum expression during the exponential phase. Primer extension analysis revealed that apf1 and apf2 harbor a putative promoter sequence that is conserved in all of the genes. Western blot analysis of the LiCl cell extracts showed that APF proteins are located on the cell surface. Intact cells of L. johnsonii revealed the typical cell wall architecture of S-layer-carrying gram-positive eubacteria, which could be selectively removed with LiCl treatment. In addition, the amino acid composition, physical properties, and genetic organization were found to be quite similar to those of S-layer proteins. These results suggest that APF is a novel surface protein of the Lactobacillus acidophilus B-homology group which might belong to an S-layer-like family.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) constitute a large family of gram-positive bacteria which are extensively applied in the fermentation of raw agricultural products and in the manufacture of a wide variety of food products (43, 44). The amount of published information concerning LAB genetics and metabolism has opened the door for new food as well as nonfood applications of these bacteria. The utilization of LAB as in vivo delivery vectors for biologically active molecules has become increasingly attractive due to their nonpathogenicity (12, 46) and their ability to survive passage through the gastrointestinal tract (12, 46). The fulfillment of these objectives requires an adequate delivery system and knowledge of the cell surface components of LAB. The cell surfaces of gram-positive bacteria cover a variety of functions, and many molecules are considered to be linked to it by different modes of anchoring (for a review, see reference 18). The lack of an outer membrane and the presence of multiple peptidoglycan layers in the cell walls of these bacteria have resulted in the use of a number of different targeting strategies that link proteins to the membrane or cell wall (10, 41). Three main strategies for anchoring on the cell surface have been identified: covalent attachment (e.g., the LPXTG-containing protein [27]), charge interactions (e.g., the S-layer protein [23]), and hydrophobic interaction (18).

The probiotic properties of LAB have stimulated various types of research on the possible roles of surface proteins in adherence to human intestinal cells (e.g., Caco2 cells). In particular, the involvement of proteinaceous bacterial surface compounds in adhesion to enterocytes has been demonstrated for many Lactobacillus species (5, 45). The cell surface of lactobacilli is poorly understood in comparison with those of the closely related streptococci and lactococci. In Lactobacillus, only S-layer proteins and a few surface enzymes, like prtB of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, have been extensively described (11). S-layers are composed of one protein known as the S-protein, with a molecular mass ranging from 40 to 60 kDa. A common feature of all surface proteins characterized so far is their ability to spontaneously crystallize into a two-dimensional layer on the outside of the bacterial cell wall (25). Previously, it had been observed that strains of Lactobacillus helveticus (7, 48, 49), Lactobacillus brevis (29), Lactobacillus acidophilus (4), Lactobacillus crispatus (45), Lactobacillus amylovorus (2), and Lactobacillus gallinarum (2) possess a surface protein (S-layer), whereas L. acidophilus group B strains (Lactobacillus johnsonii and Lactobacillus gasseri) do not appear to have an obvious S-layer (2). The primary structures of only a few Lactobacillus S-layer proteins have been determined (4, 7, 50). The predicted S-layer protein exhibits conserved C-terminal and N-terminal amino acid sequences, while the central section is highly variable. The functions of the S-layer protein in lactobacilli are largely unknown; only adhesive properties have been suggested for L. acidophilus and L. crispatus (37, 45). The ability to adhere is thought to be important to bacteria in establishing or maintaining colonization on mucosal surfaces. The S-layer of an L. acidophilus isolate has been reported to act as an afimbrial adhesin in vitro, as it is involved in the interaction with avian epithelial cells (37). In terms of adhesive capabilities, the best-characterized S-layer is that of the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida, in which the S-layer mediates bacterial adhesion to type IV collagen, lamin, fibronectin, and major components of the extracellular matrix (8, 28). Recently, it has been demonstrated that a region of the C-terminal part of the S-layer protein of L. crispatus JCM 5810 acts as a collagen-binding protein in the collagen-rich regions of the colon tissue of chickens (38). Resistance to lysozyme treatment has been related to the presence of a surface protein as the outermost envelope of L. helveticus ATCC 12046 (21). It was also suggested that the S-layer of L. helveticus strains may act as a receptor for bacteriophage adsorption (7, 48).

We are now investigating the cell surfaces of fecal isolates of L. johnsonii and L. gasseri. Here, we describe the sequences of apf1 and apf2 genes encoding a surface-located polypeptide of six different L. johnsonii and L. gasseri strains. Aggregation-promoting factor (APF) was selectively removed by extraction with 5 M LiCl and demonstrated a highly alkaline isoelectric point. It appears likely that it is anchored by electrostatic or specific noncovalent interactions on the cell wall surface and thus displays important features associated with more typical S-layer proteins of other lactobacilli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used and their characteristics are described in Table 1. Lactobacillus strains were grown in MRS broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Escherichia coli TB1, used in cloning experiments, was propagated in Luria-Bertani broth and agar (Difco) and incubated aerobically for 16 h at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study and characteristics of their APF1 and APF2 proteins

| Strain | Apf1a |

apf1

|

Apf2a |

apf2

|

% Identity (apf1-apf2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular massb | pIc | Molecular massb | pIc | ||||

| L. johnsonii ATCC 332 | 257 | 27.45 | 9.45 | 315 | 31.00 | 9.77 | 74.00 |

| L. johnsonii NCC 533 (La1) | 265 | 26.30 | 9.4 | 321 | 32.00 | 9.76 | 49.80 |

| L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 | 258 | 25.39 | 9.71 | 300 | 29.77 | 9.60 | 50.00 |

| L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 | 265 | 28.69 | 9.72 | 326 | 32.38 | 9.80 | 49.40 |

| L. johnsonii DSM 20553 | 265 | 26.29 | 9.35 | 326 | 32.37 | 9.77 | 50.00 |

| L. gasseri VPI 11759 | 302 | 29.78 | 9.98 | 297 | 29.78 | 9.98 | 95.70 |

| L. gasseri ATCC 19992 | 289 | 26.31 | 9.35 | 289 | 26.31 | 9.35 | 97.30 |

Number of amino acid residues.

The molecular mass is deduced theoretically from the amino acid sequence and is expressed in kilodaltons.

The isoelectric point value is deduced theoretically by the Emboss program.

DNA amplification and cloning of apf1 and apf2 genes.

PCR was used to amplify both apf genes in all investigated strains. DNA fragments of ∼1.0 to 1.3 kb corresponding to apf2 genes were amplified using the oligonucleotides C1 (5′-GGCAAACTAACGGTTGG-3′) and C2 (5′-GAGCACCAGTCCATGAAC-3′), while apf1 genes were amplified by employing the oligonucleotides X-ONE (5′-GTAACTTGAACACGCTTTC-3′) and X-TWO (5′-CATAAACTGTAACATAAGGC-3′) or PROM-1 (5′-GACTGACAAATATGAAAGG-3′) and PROM-2 (5′-CTATAACATAAATGCTACTAC-3′).

Each PCR mixture (50 μl) contained a reaction cocktail of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 50 pmol of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom). Each PCR cycling profile consisted of an initial denaturation step of 3 min at 95°C, followed by amplification for 30 cycles as follows: denaturation (30 s at 95°C), annealing (30 s at 54°C), and extension (2 min at 72°). The PCR was completed with an elongation phase (10 min at 72°). The resulting amplicons were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, followed by ethidium bromide staining. PCR fragments were purified using the PCR purification kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, United Kingdom) and were subsequently cloned in the pGEM-T Easy plasmid vector (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) following the supplier's instructions.

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was isolated by resuspending bacterial cell pellets in TRIzol (Gibco BRL), adding 106-μm-diameter glass beads (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and shearing the slurry with a Mini-Beadbeater-8 cell disruptor (Biospec Products, Bartiesville, Okla.), as described by Walker et al. (53). Initial Northern blot analysis of Lactobacillus apf activity was carried out on 15-μg aliquots of RNA isolated from 10 ml of Lactobacillus strains, collected after 8 or 18 h under the growth conditions described above. The RNA was separated in a 1.5% agarose-formaldehyde denaturing gel, transferred to a Zeta-Probe blotting membrane (Bio-Rad, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) according to the method of Sambrook and Russell (35), and fixed by UV cross-linking using a Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). All PCR amplicons with the primer pair C1 and C2 were radiolabeled (51). Prehybridization and hybridization were carried out at 65°C in 0.5 M NaHPO4 (pH 7.2)-1.0 mM EDTA and 7.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Following 18 h of hybridization, the membrane was rinsed twice for 30 min each time at 65°C in 0.1 M NaHPO4 (pH 7.2)-1.0 mM EDTA-1% SDS and twice for 30 min each time at 65°C in 0.1 mM NaHPO4 (pH 7.2)-1.0 mM EDTA-0.1% SDS and exposed to X-OMAT autoradiography film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Primer extension analysis.

The 5′ ends of the RNA transcripts were determined in the following manner: separate primer extension reactions were conducted with 15-μg aliquots of RNA isolated as described above and mixed with 1 pmol of primer (Laser Dye IRD800 [MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany] labeled) and 2 μl of buffer H [2 M NaCl, 50 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 6.4]. The mixture was denatured at 90°C for 5 min and then hybridized for 60 min at 42°C. After the addition of 5 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 10 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 5 μl of 0.12 M MgCl2, 20 μl of 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 0.4 μl (5 U) of reverse transcriptase (Sigma), and 49.6 μl of double-distilled water, the enzymatic reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 2 h. The reaction was stopped by adding 250 μl of an ethanol-acetone mix (1:1), and the mixture was incubated at −70°C for 15 min followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The pellets were dissolved in 4 μl of distilled water and mixed with 2.4 μl of loading buffer from the sequencing kit (fluorescence-labeled Thermo Sequenase; Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden). The cDNA was separated on an 8% polyacrylamide-urea gel, along with sequencing reactions which were conducted using the same primers employed for the primer extensions and detected using the LiCor sequencer machine (MWG Biotech). The synthetic oligonucleotides used were apf1 (5′-CTTGTTGGCCAACAGTAACTTCTGC-3′) and apf2 (5′-GCTACCAAACCAGTTGCGG-3′).

DNA sequencing.

Nucleotide sequencing of both strands from cloned DNA was performed using the fluorescence-labeled primer cycle-sequencing kit (Amersham) following the supplier's instructions. The primers used were C1, C2, PROM-1, PROM-2, X-ONE, and X-TWO labeled with IRD800.

PFGE and Southern blotting.

Agarose-embedded bacterial cells were prepared as described by Walker and Klaenhammer (52). For digestion with restriction endonuclease, cells in agarose blocks were treated with 50 U of SmaI (Roche Molecular, East Sussex, United Kingdom) as described by the manufacturer. Digestion was stopped by washing the blocks for 20 min in Tris-EDTA buffer. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed in a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field mode in a CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad). All DNA samples were separated in 1% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (35), cooled to 14°C, for 20 h at 6 V/cm, ramping the pulse time from 1 to 20 s. Southern blots of agarose gels were performed on Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham) following the protocols of Sambrook and Russell (35). The filters were hybridized with a PCR-generated probe obtained with the primer pair C1 and C2 and radiolabeled. Prehybridization, hybridization, and autoradiography were carried out according to the method of Sambrook and Russell (35).

Bioinformatic analysis of APF proteins.

Membrane-spanning regions were predicted according to an algorithm reported by Persson and Argos (31) by using the TMAP program version 46. Secondary-structure prediction was performed with the GOR Secondary Structure Prediction from the server at Southampton Bioinformatic Data Server (SBDS). The codon usage of the apf1 and apf2 genes was predicted by the GeneQuest program (DNAstar, Madison, Wis.). Isoelectric point and molecular weight predictions were performed with the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite (EBI). Multiple alignments of protein sequences were performed using the Clustal W and Genedoc programs.

Protein isolation and Western blotting.

For the isolation and purification of APF proteins, Lactobacillus strains were cultivated anaerobically in MRS broth (Difco) at 37°C for 16 h. Total surface protein extracts using 5 M LiCl were performed following the protocol described by Lortal et al. (21). Total surface protein extracts were separated by 12% Tris-HCl SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (35). Western blot analysis was performed using the Chemiluminescent Western Breeze kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). For detection of APF proteins, rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised against the conserved C-terminal peptide of APF (H2N-CADNYVKSRYGSWTG-CONH2).

Electron microscopy.

Whole cells were fixed in 3% phosphate-buffered glutaraldehyde for 15 h at 4°C and osmium tetroxide (1% [wt/vol] in the same buffer) for 15 h at 4°C, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Epon. Thin sections were poststained in aqueous uranyl and lead salts. All preparations were investigated with a Philips EM301 electron microscope at 100 kV. After LiCl treatment, all cell preparations were washed twice with distilled water before the fixation step.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All apf1 nucleotide sequences reported here have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: L. gasseri VPI 11759, AY148188; L. gasseri ATCC 19992, AF543458; L. johnsonii ATCC 332, AY148189; L. johnsonii ATCC 33200, AY148190; L. johnsonii ATCC 11506, AY148192; and L. johnsonii DSM 20553, AY148191. All apf2 nucleotide sequences reported here have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: L. gasseri VPI 11759, AF543464; L. gasseri ATCC 19992, AF543459; L. johnsonii ATCC 332, AF543460; L. johnsonii ATCC 33200, AF543461; L. johnsonii ATCC 11506, AF543463; L. johnsonii DSM 20553, AF543462; and L. johnsonii NCC 533, 548382. The 6.5-kb apf region of L. johnsonii NCC 533 has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AF548382.

RESULTS

We have recently completed the full genome sequence of L. johnsonii NCC 533 (unpublished data). The analysis of this genome has shown the presence of two tandem genes, named apf1 and apf2. The deduced amino acid sequences of these open reading frames (ORFs) were compared with protein sequences in a nonredundant peptide sequence database encompassing GenPept, TREMBL, SWISS-PROT, and PIR by using the TFASTA, FASTA, or BLASTP comparison program. The gene products showed 53 and 81% identity with the APF protein of L. gasseri IMPC 4B2 and showed ∼70% identity (>75 amino acids) with the LysM domain protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Only weak matches were detected with a hypothetical protein in S. pneumoniae. In addition, the analysis of the full genome of L. johnsonii NCC 533 has not revealed any gene which extensively matches any known S-layer nucleotide sequence.

Localization of the APF protein in L. johnsonii strains.

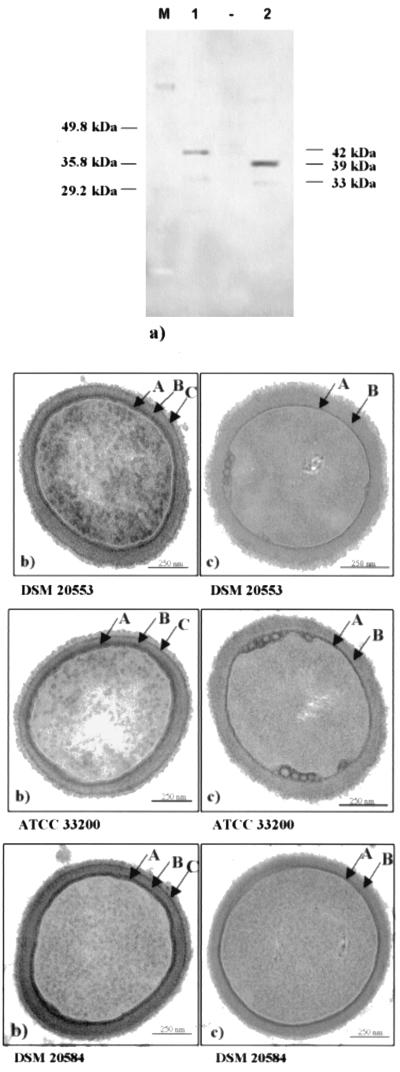

Since surface proteins are efficiently and selectively extracted by treatment with lithium chloride (21), we used the same method to isolate the APF protein from L. johnsonii strains. Sequential extraction with a 5 M LiCl solution of intact stationary-phase bacterial cells of L. johnsonii ATCC 33200, L. johnsonii DSM 20533, and L. johnsonii NCC 533 and subsequent Western blot analysis using antibodies raised against the C-terminal synthetic peptide of the APF protein yielded signals corresponding to the APF1 and APF2 proteins (Fig. 1a and data not shown). A dominant band of approximately 42 kDa and a weaker one of approximately 34 kDa were present in the extracts of L. johnsonii DSM 20533 and L. johnsonii NCC 533 (data not shown), while two bands of approximately 39 and 33 kDa were detected in the cell extracts of L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

(a) Western blot analysis with anti-APF polyclonal antibodies of proteins extracted with 5 M LiCl from L. johnsonii DSM 20533 (lane 1) and from L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (lane 2). Lane M, broad range SDS molecular marker (Bio-Rad). (b and c) Electron micrographs of whole cells of L. johnsonii DSM 20553, L. johnsonii ATCC 33200, and L. crispatus DSM 20584 stained with uranyl and lead salts showing a three-layered structure (A, B, and C), where layer C (thin dark line) corresponds to the S-layer of the cell wall in L. crispatus DSM 20584 (b), and the loss of the external layer C after 5 M LiCl treatment (c). Bars, 250 nm.

The identities of the two bands observed on Western blots were verified by overexpressing both apf genes of L. johnsonii NCC 533 individually and investigating the cellular extracts with antibodies raised against APF proteins. In immunoblotting experiments, the overexpression of the apf1 gene generated the 39-kDa band, while apf2 gene overexpression resulted in a weaker band of 33 kDa (I. Jankovic, data not shown). In addition, the N-terminal sequencing of the proteins in the Western blot with antibodies against the APF protein confirmed their specificity (M. Elli, personal communication).

Thin electron microscopic sections of L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 and L. johnsonii DSM 20553 revealed a three-layered structure (Fig. 1b). The innermost layer, representing the plasma membrane (A), was the most dense and was about 10 nm thick. The intermediate layer, the peptidoglycan-containing layer (B), was less dense and about 15 to 30 nm thick. The outermost proteinaceous layer (C) was about 10 nm thick. When the cells were treated with 5 M LiCl, layer C disappeared completely (Fig. 1c). After this treatment, the whole cells appeared rather distorted, likely due to the change in the bacterial osmotic pressure after LiCl treatment. Nevertheless, good survival of the LiCl-treated cells without the external layer C could be observed when these cells were transferred to fresh growth medium. During their growth, they rebuilt a new layer C as previously reported for S-layer proteins (22). The analysis of thin sections of L. crispatus DSM 20584, a reference strain with an S-layer (2, 38, 45), showed a similar three-layered structure, as well as the disappearance of the outermost proteinaceous layer (C) after identical treatment with 5 M LiCl.

Cloning and sequence analysis of the apf1 and apf2 genes.

Six L. johnsonii and L. gasseri strains (Table 1) were investigated for the presence of apf genes. PCR-targeted sequences were compared to the nucleotide sequences of apf1 and apf2 of L. johnsonii NCC 533. We amplified chromosomal DNA by using a set of primers targeting nucleotides of the promoter regions, as well as the 3′ end of apf1 and apf2 (Fig. 2), since these regions are highly conserved in all surface proteins previously characterized (40, 48). Notably, the amplicon sizes of apf1 and apf2 in L. johnsonii strains varied, while L. gasseri apf1 and apf2 showed identical amplicon sizes. All PCR products were cloned into the vector system pGEMT Easy and sequenced on both strands. BLAST sequence analysis revealed a very high homology (ranging from 48 to 99%) to the APF sequence of L. gasseri IMPC 4B2. The translated ORF encoded a predicted protein of 292 to 297 amino acids for apf1 and apf2 in all L. gasseri strains and 257 to 326 amino acids for the two apf genes in all L. johnsonii strains (Fig. 3). When we aligned all deduced APF1 amino acid sequences, we found high identity among the APF1 proteins of L. johnsonii ATCC 11506, L. johnsonii DSM 20553, and L. johnsonii ATCC 33200. The APF1 proteins of L. gasseri VPI 11759 and L. gasseri ATCC 19992 were almost identical, showing minor differences in only a few amino acids, while the APF1 amino acid sequence of L. johnsonii ATCC 332 depicted rather large differences in the sequence compared to the other L. johnsonii and L. gasseri strains (Fig. 3). All APF1 and APF2 amino acid sequences contained a highly conserved C terminus, while the N-terminal and middle regions showed sequence variation, including substitutions and small and/or large deletions. This suggests that the C termini of these proteins might serve the same function in all APF proteins and that it could form an independent domain involved in cell wall binding. Moreover, by using the approach of Janin et al. (15), only the middle region of the protein showed a high probability of being located on the surface. Amino acid sequence comparison of APF1 and APF2 proteins revealed that these proteins have high similarity (>95%) in L. gasseri strains, with only a few amino acid substitutions in L. gasseri ATCC 19992 and L. gasseri VPI 11759, while L. johnsonii strains, in contrast, showed a lower level of similarity (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the genetic organization of the 6.5-kb apf region. The sizes and orientations of the genes are deduced from their DNA sequences. The hairpins indicate possible rho-independent terminators. The primers used to amplify the apf genes are depicted under the arrows indicating the genes. Primers are abbreviated as follows: X1, X-ONE; X2, X-TWO; P1, PROM-1; P2, PROM-2 (C1 and C2 are full primer names).

FIG. 3.

Multiple alignments of seven pre-APF1 protein sequences (a) and seven pre-APF2 protein sequences (b). The shaded residues indicate identity among the sequences of ≥50% (black shading, 100% identity; dark gray, 80 to 99% identity; light gray, 50 to 79% identity). +, predicted α-helices; ∗, predicted β-sheets. The arrows indicate the cleavage sites of the pre-APF proteins.

Since APF proteins are secreted on the cell surface, both apf1 and apf2 have signal peptides, resulting from cleavage by signal peptidase I (54). The predicted cleavage site is located between asparagine residues 28 and 29 in APF1 of L. johnsonii ATCC 11506, L. johnsonii DSM 20553, and L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 and between asparagine and serine residues 25 and 26 of L. gasseri ATCC 19992, L. gasseri VPI 11759, and L. johnsonii ATCC 332 (Fig. 3). This indicates that all APF2 proteins and APF1 of L. gasseri VPI 11759, L. gasseri 19992, and L. johnsonii ATCC 332 strains have a signal peptide of 25 amino acids and that the N terminus complies with the rules of Von Heijne (51) for genuine prokaryotic signal sequences. The theoretically deduced molecular mass of mature APF1 ranges from 26.29 to 29.78 kDa, while that of APF2 ranges from 26.31 to 32.37 kDa (Table 1), which is not in full accordance with the molecular mass determined by Western hybridization (Fig. 1). This might indicate possible posttranslation modification (e.g., glycosylation) of the APF proteins. The APF1 and APF2 proteins are positively charged, with a predicted isoelectric point of 9.60 to 9.84 (Table 1). Additional characteristic features of L. johnsonii and L. gasseri APF proteins include a low content of sulfur-containing amino acids but high contents of threonine, alanine, serine, glycine, and glutamine. APF1 is extremely rich in glutamine residues, and surface probability plots indicate that most of the glutamine residues might be exposed at the protein surface.

The codon usage predictions for apf1 and apf2 for all strains used in this study showed that glutamine uses a unique codon (CAA), as do threonine (ACU) and glycine (GGU). These three codons are also the more frequently used codons in the genome of L. johnsonii NCC 533 (unpublished data). However, the tyrosine residues in both apf genes use a codon (UAC) that is rarely used for L. johnsonii NCC 533 (unpublished data). Interestingly, two glutamine tRNAs and one tyrosine tRNA are transcribed from the region downstream of the apf genes in L. johnsonii NCC 533 and exhibit anticodons perfectly matching the codons for glutamine and tyrosine (Fig. 2). Secondary-structure prediction for the APF1 protein gave a high content (ranging from 28.5% in L. gasseri VPI 11759 to 32.3% in L. johnsonii ATCC 11506) of β-sheet, while APF2 proteins depicted a smaller β-sheet content (from 26.1 to 27%), as observed for CbsA of L. crispatus JCM 5810 (38). Alignment-based secondary-structure prediction (Fig. 3) showed that the whole protein consists of alternating regions of β-strand and α-helical regions.

Transcriptional analysis of the apf gene.

In order to verify if and under which conditions the apf1 and apf2 genes are expressed, we investigated total RNAs extracted from exponentially growing and stationary-phase L. johnsonii and L. gasseri cells with probes targeting the 5′ ends of apf1 and the 3′ ends of apf2 genes. Northern hybridizations revealed two distinct signals, indicating individual mRNA transcripts for the apf1 and apf2 genes of about 800 and 1,000 nucleotides for all L. johnsonii strains, with the exception of L. johnsonii ATCC 332 (Fig. 4). In all L. gasseri strains and L. johnsonii ATCC 332, we could observe a transcript consisting of approximately 1,000 nucleotides for both genes (Fig. 4). Transcription analysis demonstrated that apf1 and apf2 gene expression depends upon the growth phase, with the maximum level occurring during the early stages of growth. The 5′ ends of the transcripts were mapped by primer extension analysis. Primer extension confirmed independent transcription of the two genes (Fig. 5a and b). Primer extension experiments located the 5′ end 37 bp upstream of the start codon of the apf2 gene, and two transcription start sites were located upstream of the start codon of the apf1 gene. The analysis of the putative promoter regions revealed that a potential promoter-like sequence having putative −10 hexamers (TATTAT) was present in all apf1 and apf2 sequences investigated. While the −35 region, which resembles the consensus E. coli σ70 and Bacillus subtilis σ43 recognition sequences (TTGACA) (13, 26), was found at a suboptimal distance of 11 bases upstream of the −10 region (Fig. 5b) in the putative promoter sequences of apf2, no recognizable −35 box was detected in the putative promoter region of apf1. The promoters of both apf1 and apf2 displayed a TG motif at −13 and −14 as an upstream extension of the −10 hexamer. In addition, we found a 20-bp A+T-rich DNA sequence, located upstream of the promoter between nucleotides −40 and −60, which resembled upstream promoter elements (34).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of L. gasseri and L. johnsonii apf1 and apf2 gene transcripts by using a probe covering the 5′ end of apf1 and the 3′ end of apf2. Lane 1, L. gasseri VPI 11759 (RNA from exponential growth phase); lane 2, L. gasseri VPI 11759 (RNA from stationary growth phase); lane 3, L. gasseri ATCC 19992 (RNA from stationary growth phase); lane 4, L. gasseri ATCC 19992 (RNA from exponential growth phase); lane 5, L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 (RNA from exponential growth phase); lane 6, L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 (RNA from stationary growth phase); lane 7, L. johnsonii DSM 20553 (RNA from exponential growth phase); lane 8, L. johnsonii DSM 20553 (RNA from stationary growth phase); lane 9, L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (RNA from exponential growth phase); lane 10, L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (RNA from stationary growth phase); lane 11, L. johnsonii ATCC 332 (RNA from exponential growth phase); lane 12, L. johnsonii ATCC 332 (RNA from stationary growth phase). The estimated sizes of the detected transcripts are indicated.

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis and comparison of the putative promoter sequences of the apf1 gene (a) and the apf2 gene (b). Computer predictions of the secondary structure of the untranslated leader sequence of mRNA are directed by the putative promoter P2-a (c). (a and b) P-1a indicates the putative promoter P-1a, while P-2a indicates the putative promoter P-2a. Underlined boldface type, −10 and −35 boxes; solid shading, TG doublet of extended −10 sequence; SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence; REP, direct repeats in the −35 box; boldface type (TT, GC, TG) indicates transcription start point. The start codon is given at the right end of the sequence. Lanes 1, L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 (RNA from the exponential growth phase); lanes 2, L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 (RNA from the stationary growth phase); lanes 3, L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (RNA from the exponential growth phase); lanes 4, L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (RNA from the stationary growth phase); lanes 5, L. johnsonii DSM 20553 (RNA from the exponential growth phase); lane 6, L. johnsonii DSM 20553 (RNA from the stationary growth phase); lane 7, L. johnsonii ATCC 332 (RNA from the exponential growth phase); lane 8, L. johnsonii ATCC 332 (RNA from the stationary growth phase); lane 9, L. gasseri ATCC 19992 (RNA from the exponential growth phase); lane 10, L. gasseri ATCC 19992 (RNA from the stationary growth phase); lane 11, L. gasseri VPI 11759 (RNA from the exponential growth phase); lane 12, L. gasseri VPI 11759 (RNA from the stationary growth phase).

Multiple promoter structures have been found preceding the apf1 gene. In fact, two transcription start sites were identified at −67 bp (putative promoter P-1a) and at −126 bp (putative promoter P-2a) relative to the start of the coding sequence (Fig. 5a). The putative promoter P-2a showed a −10 box (TAACAA), but no consensus −35 sequence was observed. Interestingly, two direct repeats (AATATT) were detected about 10 bp upstream of the −10 box for both start sites. Computer analysis of the secondary structure of the untranslated leader sequence of the putative P-2a promoter predicted the formation of an extensive hairpin-like structure (Fig. 5c). According to this computer prediction, the first nucleotides of the 5′ end are involved in stem formation and the ribosome-binding site in the predicted secondary structure is exposed in a loop. Based on detailed computer analysis, the untranslated leader sequence of mRNA directed by the putative promoter P-1a could also fold into a stable structure, with the 5′ end of the hypothetical mRNA again being part of the stem structure. Furthermore, two stem-loops resembling rho-independent terminators were detected downstream of the translation end of the apf1 and apf2 genes of the Lactobacillus strains listed in Table 1. The gene preceding apf1 also ends with a potential transcription terminator structure with a free energy of −19.9 kcal/mol, while the region immediately downstream of the apf2 gene showed a rho-independent terminator with a calculated free energy of −13.2 kcal/mol. Thus, apf1 and apf2 genes are expected not to be cotranscribed with other adjacent genes and also not together, since the intergenic region contains another rho-independent terminator (Fig. 2). The apf1 and apf2 ORFs are preceded by putative ribosome-binding sites (GGAGAG and AGGAAG) located 15 and 7 bp upstream of the translation initiation codons, respectively.

Location of the apf1 and apf2 genes in the Lactobacillus genome.

The locations of the apf1 and apf2 genes in the genomes of all of the strains used in this study were determined by transferring the SmaI-digested genome fragments to a nylon filter and probing them with a DNA fragment containing the 5′ region of the apf1 gene and the whole apf2 gene by Southern blot hybridization. In Southern blots of SmaI digests, L. gasseri VPI 11759, L. gasseri ATCC 19992, L. johnsonii ATCC 332, and L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 showed identical signals corresponding to a 55-kb-long SmaI DNA fragment. In L. johnsonii NCC 533 and L. johnsonii DSM 20553, the apf1 and apf2 genes were in the same 234-kb SmaI fragment, while in L. johnsonii ATCC 33200, apf1 and apf2 were located in a smaller 40-kb SmaI DNA fragment (data not shown). The availability of the full genome sequence of L. johnsonii NCC 533 provided us with the likely gene arrangements surrounding apf1 and apf2 in closely related L. johnsonii strains (like DSM 20553). In fact, the similar PFGE profiles of L. johnsonii NCC 533 and L. johnsonii DSM 20533 suggested that these strains are phylogenetically closely related to each other, even though they are not identical as determined with molecular typing tools (amplified fragment length polymorphism, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR, repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR, and single triplicate arbitrarily primed PCR) (data not shown). Moreover, we investigated the regions surrounding the apf genes in all of the Lactobacillus strains used in this study by using PCR primers designed on the basis of the nucleotide sequences of L. johnsonii NCC 533 (data not shown), targeting various 6.5-kb regions containing apf genes. The gene compositions of all investigated Lactobacillus regions were found to be identical to that of L. johnsonii NCC 533. The apf1 gene of L. johnsonii NCC 533 is preceded by two ORFs, orf1 and orf2, while the apf2 gene is followed by two tRNAs encoding glutamine, a tRNA encoding tyrosine, and three other ORFs, orf3, orf4, and orf5 (Fig. 2). BLAST analysis of orf1 and orf2 gave positive matches with a predicted membrane protein (accession number AE007676_2) of Clostridium acetobutylicum (32% identity) and with the predicted acetyltransferase (accession number AE007773_1) of C. acetobutylicum (28% identity), respectively. orf3 showed 78% identity with a hypothetical protein of Listeria innocua (accession number AL596172_230) and with a transmembrane protein of Sinorhizobium meliloti (accession number AL591784) and of Ralstonia solanacearum (accession number AL646060_88). orf4 gave no positive alignments with any protein available in the databases searched. Furthermore, orf5 showed 43% identity with the hydroxyisocaproate dehydrogenase of E. coli (accession number A22409_1).

DISCUSSION

This paper describes for the first time the occurrence of tandem genes encoding surface proteins in L. johnsonii and L. gasseri strains. The proteins encoded by the apf1 and apf2 genes possess all of the necessary characteristics of surface proteins, such as limited sulfur-containing amino acids, a high content of threonine and serine, and a high content of hydrophobic amino acids. Moreover, a common characteristic of Lactobacillus S proteins is a high isoelectric point that confers a positive charge on various proteins with otherwise limited amino acid sequence similarity (4, 38, 40).

The APF proteins of L. johnsonii and L. gasseri are sequentially encoded by two tandem genes that are separated by a short intergenic region. A similar situation is also found for the S-layer protein in some organisms, such as Aquaspirillum serpens, Bacillus brevis (47), Bacillus stearothermophilus (16, 36), and Thermus thermophilus (14). Moreover, the presence of two copies of the S-layer gene have been described for L. acidophilus ATCC 4356 (4) and L. crispatus JCM 5810 (45), in which two surface protein-encoding genes (slpA and slpB) are located in opposite orientations on the same chromosomal segment. The amino acid compositions and predicted physical properties (such as isoelectric point and structure) of the deduced mature APF1 and APF2 proteins are very similar. The corresponding genes are almost identical in their 3′ ends. It is tempting to speculate that the C-terminal parts of the APF1 and APF2 proteins might be important for any proper functioning, like the attachment of the APF protein to the underlying cell wall. An explanation for the presence of two different copies of apf genes in L. johnsonii might be that these bacteria face different environmental conditions in nature. These different conditions, and the presence of numerous microorganisms competing for the same substrates and possibly the same receptors, could provide the selective pressure for APF variation in L. johnsonii. A report concerning the S-layers of different B. stearothermophilus strains showed that a change in environmental conditions (such as oxygen pressure) can be the inducing or selecting determinant for the type of S-layer produced (36). For all genes that are transcribed at a high rate, a biased codon usage was observed (32). Over 50% of the APF proteins are encoded by only seven triplets. Several short direct repeats that result in amino acid repeats which could lead to DNA rearrangement have been found in apf1 and apf2 genes. Additionally, many direct repeats have been identified in the DNA sequences of S-layer genes (8, 16), once again resulting in DNA rearrangements.

The apf1 gene has a multiple-promoter structure, which has been described previously, preceding several S-protein genes, including the S-layer gene of L. brevis (50) and the S-layer gene of L. acidophilus ATCC 4356 (4). Transcription directed by a multiple-promoter structure might contribute to a larger amount of mRNA than transcription directed by only a single promoter; however, this is in fact rather unlikely, because expression levels of apf1 and apf2 in Northern blot hybridization and primer extension experiments are highly similar. An alternative reason for the observed multiple-promoter structure might be sequential activity of these two promoters under different induction conditions. So far, we have not identified the regulation mechanism for these genes. Efficient production of S-proteins is often directed by an mRNA which is considerably more stable than average mRNAs of the same species. The long half-lives of mRNAs of S-proteins, ranging from 10 to 22 min, seem to be due to the formation of a hairpin-like structure by the 5′-untranslated leader sequence of mRNAs, which should prevent mRNA degradation by RNase E (6). In this study, we showed that the same long untranslated leader sequence is present in the apf1 mRNA and is predicted to fold into a stable secondary structure similar to those of S-layer genes (3). The promoter regions of both apf1 and apf2 genes exhibit a TG motif as an upstream extension of the −10 box. It has been shown that this motif is also conserved in certain E. coli strains (17), in early promoters of phage SPO1 (42), and in L. lactis (19). The TG motif is responsible for the increased transcriptional activity of the extended −10 regions.

The APF protein was originally identified by immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts of L. gasseri IMPC 4B2 and has been suggested to contribute to the aggregation phenotype of this strain, consequently being named APF (33). In this report, we have shown that APF proteins are present in many strains of the L. acidophilus B group that do not exhibit an aggregation phenotype. Moreover, overexpression of apf genes originating from L. gasseri IMPC 4B2 and cloned into L. johnsonii NCC 533, a nonaggregating strain, did not result in clumping of cells (Jankovic, data not shown). It has been shown that cell surface composition involves rather complex compounds (e.g., polysaccharides, hydrocarbon-like compounds, and proteins) postulated to be responsible for physiochemical properties contributing to cell interaction (1). Thus, aggregation is a rather complex phenomenon due to many physical and chemical forces that can drive the interaction between cell surfaces and proteins. APF proteins could participate in the development of such an autoagglutination of bacterial cells, as reported for S-layer proteins in some Bacillaceae and Archaeobacteria (25), by physically masking the negatively charged peptidoglycans. Also, the positively charged APF proteins could facilitate adsorption to negatively charged bacteria.

Only a few functions have been assigned to S-layer proteins, such as forming barriers between cells and environments (30) and acting as an attachment structure for extracellular enzymes (24), but no general function could be related to S-layers. Similarly, the physiological role of the Lactobacillus APF proteins remains unknown. Unfortunately, all attempts to inactivate both apf1 and apf2 genes in L. johnsonii NCC 533 have been unsuccessful (data not shown), as have similar attempts to knock out S-layer genes in lactobacilli (29).

Thin sections of L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 and L. johnsonii DSM 20553 in transmission electron microscopy revealed a three-layered structure. An identical organization has been described in L. helveticus ATCC 12046, where the outermost layer (the analog of layer C [Fig. 1b]) has been demonstrated by freeze-etching experiments to represent the paracrystalline lattice (20, 21, 22). The cell shape of L. johnsonii NCC 533 changed upon overexpression of apf genes, suggesting that APF might be involved in the structure of the cell envelope (Jankovic, data not shown). This could indicate that APF plays an important but so far unknown role for the cell, where inactivation is lethal, and this situation is typical for genes responsible for cell shape (9). In gram-negative Archaebacteria, S-layers are involved in determining cell shape and in the cell division process (39). Moreover, deletions of the S-layer gene in Bacillus anthracis resulted in dramatic morphological changes (from rod-shaped to long and filamentous morphotype) (46). The amino acid compositions, physical properties, and genetic organizations of APF proteins are similar to those of S-layer proteins, suggesting that APF might correspond to S-layer proteins in L. johnsonii and L. gasseri. The limited amino acid similarity of APF proteins (an overall similarity of <48% at the DNA level and only 20% at the protein level) with S-layer proteins is not surprising, since the primary structures of the S-layer proteins of lactobacilli exhibit marked variability, even among isolates representing the same homology group of the former L. acidophilus cluster (2). From the secondary-structure data of S proteins examined so far, it is possible that S proteins are generally composed of β-sheets with some α-helices, similar to the arrangement in the APF protein. Since APF proteins form the outermost layer of L. johnsonii and L. gasseri, these proteins could be highly attractive candidates for fusions with antigenic determinants. The possibility of genetically manipulating lactobacilli and the availability of these apf genes in probiotic strains (such as L. johnsonii NCC 533) open potential new areas of research for the expression of foreign proteins (e.g., antigens) on bacterial surfaces.

The results reported here should be used as the basis for further work to identify the specific roles of APF proteins and to determine the basis of the interaction between these proteins and the bacterial cell, as well as the host cell surface. The presence of a surface protein layer, with characteristics similar to crystalline S-layer proteins, was recently demonstrated for L. johnsonii and L. gasseri in our laboratory (P. Schäer Zammaretti, unpublished data). Future studies will include freeze-etching experiments in order to fully characterize the structure of the APF proteins and to analyze their potential crystalline-array morphology.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people at NRC (Lausanne, Switzerland): A. Mercenier for constructive and critical reading of the manuscript; M.-L. Dillmann, P. Schär-Zammaretti, and J. Ubbink for excellent discussions about electron microscopic images; and V. Meylan for her excellent technical assistance. The EM picture was provided courtesy of P. Schär-Zammaretti, M.-L. Dillmann, and J. Ubbink. Finally, we thank M. Elli (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Piacenza, Italy) for discussing and sharing unpublished data with us.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boonaert, C. J., and P. G. Rouxhet. 2000. Surface of lactic acid bacteria: relationships between chemical composition and physiochemical properties. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2548-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boot, H. J., C. P. A. M. Kolen, B. Pot, K. Kersters, and P. H. Pouwels. 1996. The presence of two S-layer protein encoding genes is conserved among species related to Lactobacillus acidophilus. Microbiology 142:2375-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boot, H. J., P. A. Carin, C. P. A. M. Kolen, F. J. Andreadaki, R. J. Leer, and P. H. Powels. 1996. The Lactobacillus acidophilus S-layer protein gene expression site comprises two consensus promoter sequences, one of which directs transcription of stable mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 178:5388-5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boot, H. J., C. P. A. M. Kolen, J. M. van Noort, and P. H. Pouwels. 1993. S-layer protein of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356: purification, expression in Escherichia coli, and nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene. J. Bacteriol. 175:6089-6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boris, S., J. E. Suarez, and C. Barbes. 1997. Characterization of the aggregation promoting factor from Lactobacillus gasseri, a vaginal isolate. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvet, P., and J. G. Belasco. 1992. Control of RNase E-mediated RNA degradation by 5′ terminal base pairing in E. coli. Nature 360:488-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callegari, M. L., R. Riboli, J. W. Sanders, J. Kok, G. Venema, and L. Morelli. 1998. The S-layer gene of Lactobacillus helveticus CNRZ 892: cloning, sequence and heterologous expression. Microbiology 144:719-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu, S., S. Cavaignac, J. Feutrier, B. M. Phipps, M. Kostrzynska, W. W. Kay, and T. J. Trust. 1991. Structure of the tetragonal surface virulence array protein and gene of Aeromonas salmonicida. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15258-15265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa, C. S., and D. N. Anton. 1993. Round-cell mutants of Salmonella typhimurium produced by transposition mutagenesis: lethality of rodA and mre mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 236:387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischetti, V. A., D. Medaglini, and G. Pozzi. 1993. Expression of foreign proteins on Gram-positive commensal bacteria for mucosal vaccine delivery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 4:603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert, C., D. Atlan, B. Blanc, R. Portalier, L. Lapierre, and B. Mollet. 1996. A new cell surface proteinase: sequencing and analysis of the prtB gene from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. J. Bacteriol. 178:3059-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilliland, S. E. 1990. Health and nutritional benefits of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 87:175-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1983. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:2237-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrero, L. A. F., G. Olabarria, and J. Berenguer. 1997. The S-layer of Thermus thermophilus HB8: structure and genetic regulation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:65-67. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janin, J., S. Wodak, M. Levitt, and B. Maigret. 1978. Conformation of amino acid side chains in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 125:357-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuen, B., U. B. Sleytr, and W. Lubitz. 1994. Sequence analysis of the sbsA gene encoding the 130 kDa surface-layer protein of Bacillus stearothermophilus strain PV72. Gene 145:115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar, A., R. A. Malloch, N. Fujita, D. A. Smillie, A. Ishihama, and R. S. Hayward. 1993. The minus 35 recognition region of Escherichia coli sigma 70 is inessential for initiation of transcription at an “extended minus 10” promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 232:406-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leenhouts, K., G. Buist, and J. Kok. 1999. Anchoring of proteins to lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 76:367-376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, C. Q., M. L. Harvey, and N. W. Dunn. 1997. Cloning of a gene encoding nisin resistance from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis M189 which is transcribed from an extended −10 promoter. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 43:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lortal, S., M. Rousseau, P. Boyaval, and J. van Heijenoort. 1991. Cell wall and autolytic system of Lactobacillus helveticus ATCC 12046. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:549-559. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lortal, S., J. van Heijenoort, K. Gruber, and U. B. Sleytr. 1992. S-layer of Lactobacillus helveticus ATCC 12046: isolation, chemical characterization and reformation after extraction with lithium chloride. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:611-618. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lortal, S. 1997. The paracrystalline surface-layer of Lactobacillus helveticus. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:32-36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masuda, K., and T. Kawata. 1983. Distribution and chemical characterization of regular arrays in the cell walls of strains of the genus Lactobacillus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 20:145-150. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matuschek, M., G. Burchhardt, K. Sahm, and H. Bahl. 1994. Pullulanase of Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurigenes EM1: molecular analysis of the gene, composite structure of the enzyme, and a common model for its attachment to the cell surface. J. Bacteriol. 176:3295-3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messner, P., and U. B. Sleytr. 1992. Crystalline bacterial cell-surface layers. Adv. Microbiol. Physiol. 33:214-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moran, C. P., N. Lang, S. F. J. LeGrice, G. Lee, M. Stephen, A. L. Sonenshein, J. Pero, and R. Losick. 1982. Nucleotide sequences that signal the initiation of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 186:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navarre, W. W., and O. Schneewind. 1994. Proteolytic cleavage and cell wall anchoring at the LPXTG motif of surface proteins in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 14:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noonan, B., and T. J. Trust. 1997. The synthesis, secretion and role in virulence of the paracrystalline surface protein layers of Aeromonas salmonicida and A. hydrophila. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 154:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palva, A. 1997. Molecular biology of the Lactobacillus brevis S-layer gene (slpA) and utility of the slpA signals in heterologous protein secretion in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:83-88. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paula, S. J., P. S. Duffey, S. L. Abbott, R. P. Kokka, L. S. Oshiro, J. M. Janda, T. Shimada, and R. Sakazaki. 1988. Surface properties of autoagglutinating mesophilic aeromonads. Infect. Immun. 56:2658-2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persson, B., and P. Argos. 1994. Prediction of transmembrane segments in proteins utilising multiple sequence alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 237:182-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pouwels, P. H., and J. A. M. Leunissen. 1994. Divergence in codon usage of Lactobacillus species. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:929-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reniero, R., P. Cocconcelli, and L. Morelli. 1992. High frequency of conjugation in Lactobacillus mediated by an aggregation-promoting factor. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:763-768. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α-subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 262:1407-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Sara, M., and U. B. Sleytr. 1994. Comparative studies of S-layer proteins from Bacillus stearothermophilus strains expressed during growth in continuous culture under oxygen-limited and non-oxygen-limited conditions. J. Bacteriol. 176:7182-7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneitz, C., L. Nuotio, and K. Lounatman. 1993. Adhesion of Lactobacillus acidophilus to avian intestinal epithelial cells mediated by crystalline bacterial cell surface layer (S-layer). J. Appl. Bacteriol. 74:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sillanpaa, J., B. Martinez, J. Antikainen, T. Toba, N. Kalkkinen, S. Tankka, K. Lounatmaa, J. Keranen, M. Hooh, B. Westerlund-Wikstrom, P. H. Pouwels, and T. K. Korhonen. 2000. Characterization of the collagen-binding S-layer protein CbsA of Lactobacillus crispatus. J. Bacteriol. 182:6440-6450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sleytr, U. B., P. Messner, D. Pum, and M. Sara. 1993. Crystalline bacterial cell surface layers. Mol. Microbiol. 10:911-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smit, E., F. Oling, R. Demel, B. Martinez, and P. H. Pouwels. 2001. The S-layer protein of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356: identification and characterization of domains responsible for S-protein assembly and cell wall binding. J. Mol. Biol. 305:245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stahl, S., and M. Uhlen. 1997. Bacterial surface display: trends and progress. Trends Biotechnol. 15:185-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart, C. R., I. Gaslightwala, K. Hinata, K. A. Krolikowski, D. S. Needlemam, A. Ahu-Yuen Peng, M. A. Peterman, A. Tobias, and P. Wei. 1998. Genes and regulatory sites of the “host-takeover module” in the terminal redundancy of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPO1. Virology 246:329-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stiles, M., and W. Holzapfel. 1997. Lactic acid bacteria of foods and their current taxonomy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 36:1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tannock, G. W. 1994. The acquisition of the normal microflora of the gastrointestinal tract, p. 1-16. In S. A. Gibson (ed.), Human health: the contribution of microorganisms. Springer, London, United Kingdom.

- 45.Toba, T., R. Virkola, B. Westerlund, Y. Bjorkman, J. Sillanpaa, T. Vartio, N. Kalkkinen, and T. K. Korhonen. 1995. A collagen binding S-layer protein in Lactobacillus crispatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2467-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toumelin, E. I., J. C. Sirad, E. Duflot, M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 1995. Characterization of Bacillus anthracis S-layer: cloning and sequencing of the structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:614-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuboi, A., R. Uchihi, R. Tabata, Y. Takahashi, H. Hashiba, T. Sasaki, H. Yamagata, N. Tsukagoshi, and S. Udaka. 1986. Characterization of the genes coding for two major cell wall proteins from protein producing Bacillus brevis 47: complete nucleotide sequence of outer wall protein gene. J. Bacteriol. 168:365-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ventura, M., M. L. Callegari, and L. Morelli. 1999. Surface layer variations affecting phage adsorption on seven Lactobacillus helveticus strains. Ann. Microbiol. Enzymol. 49:55-63. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ventura, M., M. L. Callegari, and L. Morelli. 2000. S-layer gene as a molecular marker for identification of Lactobacillus helveticus. FEMS Micobiol. Lett. 189:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vidgren, G., I. Palva, R. Pakkanen, K. Lounatmaa, and A. Palva. 1992. S-layer protein gene of Lactobacillus brevis: cloning by polymerase chain reaction and determination of the nucleotide sequence. J. Bacteriol. 174:7419-7427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Von Heijne, G. 1986. Signal sequences: the limit of variation. J. Mol. Biol. 184:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker, D. C., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1994. Isolation of a novel IS3 group insertion element and construction of an integration vector for Lactobacillus spp. J. Bacteriol. 176:5330-5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker, D. C., H. S. Girgis, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1999. The groESL chaperone operon of Lactobacillus johnsonii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3033-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wickner, W. 1980. Assembly of protein into membranes. Science 210:861-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]