Abstract

DNA and protein precursors were incorporated into trichloroacetic acid-precipitated material by bacterial cell suspensions during incubation for 50 to 100 days at −15oC. Incorporation did not occur at −70oC and was inhibited by antibiotics. The results demonstrate that bacteria can perform macromolecular synthesis under conditions that mimic entrapment in glacial ice.

Bacteria can remain viable for hundreds of thousands of years when trapped in glacial ice (1, 2, 8 [http://www.ohiolink.edu/etd/send-pdf.cgi?osu1015965965], 9). In the absence of repair, macromolecular damage must accumulate through amino acid racemization, DNA depurination, and exposure to natural ionizing radiation (12, 13). However, it is known that temperature and the presence of water strongly influence macromolecular decay and that protein and nucleic acid decay rates are drastically reduced within materials with low water activity, such as amber (4) and perhaps ice as well. It also seems possible that such entrapped microbes might carry out slow rates of metabolism to repair the incurred macromolecular damage. Thin veins of liquid exist between ice crystals that could provide a habitat for microorganisms within apparently solid ice (15), and studies of permafrost (17) and South Pole snow (6) have detected low levels of metabolic activity at subzero temperatures. Therefore, to explore the concept that microorganisms trapped in glacial ice might also be metabolically active, reconstruction experiments were undertaken to determine if macromolecular synthesis occurs at −15°C when bacteria isolated from glacial ice core samples were refrozen.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

A γ-proteobacterial Psychrobacter species (8) (isolate Trans1; 16S ribosomal DNA [rDNA] GenBank accession no. AF479327) and Escherichia coli (Ohio State reference no. 422) were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (18), and an actinobacterial Arthrobacter species (7) (isolate G200-C1; 16S rDNA GenBank accession no. AF479341) was cultured in R2 medium (16). Cultures (25 ml) were incubated aerobically with shaking (200 rpm) at 22°C in 125-ml Erlenmeyer flasks to the late exponential growth phase and were diluted to an initial A600 of 0.2 and allowed to grow to an A600 of 0.6. The cells present were then harvested by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 5 min, washed twice with distilled water, and resuspended at an A600 of 0.2 in distilled water (equivalent to 1.3 × 108 and 2 × 108 CFU ml−1 for Trans1 and G200-C1, respectively). Aliquots (500 μl) of these cell suspensions were placed in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and chilled to 4°C.

Precursor incorporation assays.

Cell suspensions were maintained on ice, and 100 μl of a chilled working solution (10 μCi ml−1; diluted 1:100 from stock) of either [3H]thymidine (ICN Biomedicals, catalog no. 24060; 60 to 90 Ci/mmol in sterile water) or [3H]leucine (ICN Biomedicals, catalog no. 20036E; 40 to 60 Ci/mmol in a sterile 2:98 ethanol-water mixture) was added to each sample, and the mixture was rapidly frozen by incubation at −70°C. After 1 h at −70°C, tubes were transferred to a −15°C freezer, except for control cell suspensions that were maintained at −70°C. At designated experimental time points, 100 μl of 50% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to a frozen mixture, which was then allowed to melt at 4°C. After 30 min at 4°C, the TCA-insoluble macromolecules were sedimented by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed with 500 μl of 5% TCA, recentrifuged for 10 min at 18,000 × g, washed with 500 μl of 70% ethanol, and suspended in 1 ml of Ecoscint H scintillation fluid (Life Sciences, Inc., catalog no. LS-275). The Eppendorf tube was placed into a scintillation vial, and the radioactivity present was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting (Beckman model LS-7500 scintillation counter).

Incorporation into TCA-precipitable material at −15°C.

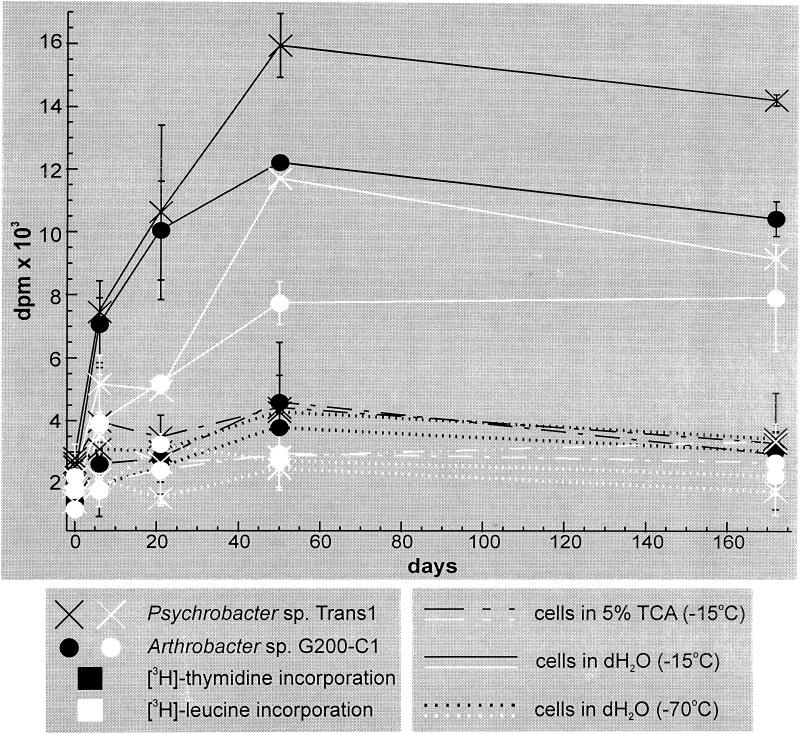

[3H]thymidine and [3H]leucine were incorporated into TCA-precipitated material by cells frozen in distilled water during incubation at −15°C (Fig. 1). The majority of the incorporation occurred within the first 50 days after freezing. Incorporation did not occur in identical samples incubated at −70°C, a temperature below that predicted for liquid water to exist in ice (14), or by controls pretreated with 5% TCA before freezing. The radioactive counts observed in TCA-treated controls were similar in samples incubated at −15 and 22°C (1,000 to 5,000 dpm), indicating that ∼0.2% of the radiolabel persisted following ∼1:1,000 dilution of the mixture during precipitation and washing. Since there is not a significant difference between the radioactive counts obtained in samples prefixed in TCA and those incubated at −70°C in distilled water, this suggests that the background in these experiments results from persistence of residual radiolabel and is not due to acid conditions effecting chemical binding.

FIG. 1.

Incorporation of [3H]thymidine and [3H]leucine into TCA-precipitable material over 172 days by frozen suspensions of Psychrobacter sp. strain Trans1 and Arthrobacter sp. strain G200-C1 at −15 and −70°C. Duplicate samples were measured at each time point. The y-axis error bars denote standard deviations from the mean.

No precursors were incorporated after >5 months at −15°C by cells frozen in their respective growth media (data not shown). The presence of substrate in these undefined media may have diluted the radiolabel and prevented detection of a low level of incorporation over this period of time. Another explanation is that nutrient-fed cultures were not metabolically stressed prior to freezing, as would occur when cells in logarithmic growth were washed and reconstituted in distilled water. During metabolic arrest, the imbalance between decreased anabolism and continuing catabolism causes a burst of free radical production, resulting in damage to DNA and other cellular components (3). It is possible that incorporation by cells in ice made from distilled water represents activity directed toward repair of damage incurred prior to freezing.

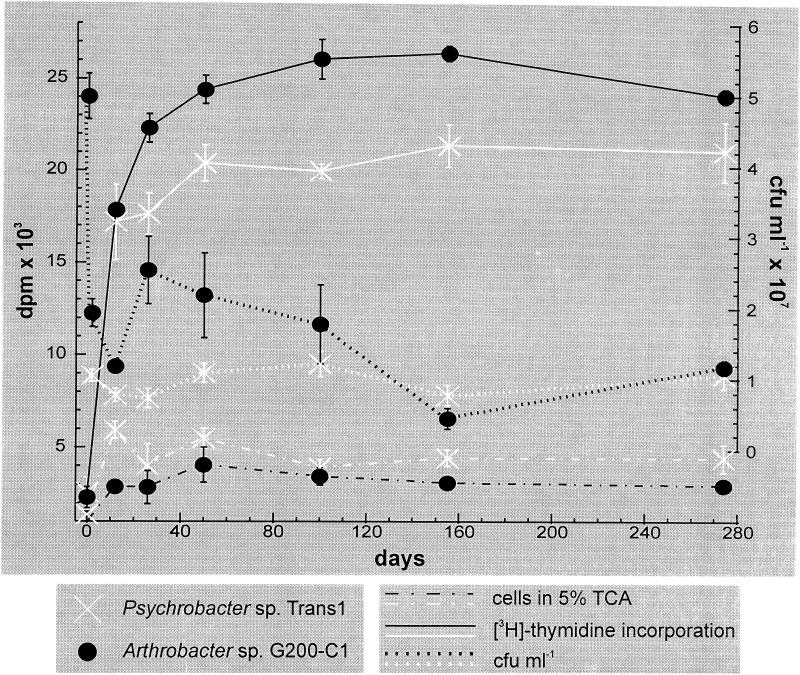

In experiments in which the viable count was also determined, the recovery of G200-C1 decreased fourfold during the freezing process and then an additional fourfold during the first 12 days of incubation at −15°C (Fig. 2). Due to a technical error, a day 0 time point is not available for the Trans1 isolate, but the viable count was 12-fold lower after 2 days at −15°C than before freezing. In both cases, the numbers of CFU per milliliter recovered stabilized by 150 days postfreezing. Interestingly, 70 to 80% of the thymidine incorporation occurred during the first 12 days of incubation, and this coincided with the period of time when the numbers of CFU per milliliter became stable, after the initial 17-fold decrease that occurred during freezing and initial storage for 12 days at −15°C. The presence of ciprofloxacin (ICN Biomedicals, catalog no. 199020) reduced thymidine incorporation by 30 to 40%, and the presence of chloramphenicol (Sigma, catalog no. 100K9113) reduced leucine incorporation 50 to 60% (Table 1). Curiously, incubations in the presence of nalidixic acid (Sigma, catalog no. N-3143), resulted in a twofold increase in thymidine incorporation in both species, even though growth of G200-C1 is inhibited in the presence of 15 μg of this antibiotic per ml. Precursor incorporation was similarly affected in aqueous cell suspensions incubated at 22°C for 20 h in the presence of chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid (data not shown). Although the amount of incorporation under liquid conditions after 20 h at 22°C was substantially larger (10 to 100×) than after 23 days at −15°C, leucine incorporation was 25 to 85% lower in the presence of chloramphenicol, and thymidine incorporation increased twofold in the presence of nalidixic acid.

FIG. 2.

Incorporation of [3H]thymidine and numbers of CFU per milliliter for Psychrobacter sp. strain Trans1 and Arthrobacter sp. strain G200-C1 over 274 days of incubation at −15°C. Before freezing, the cell suspensions of Trans1 and G200-C1 contained 1.3 × 108 CFU ml−1 and 2 × 108 CFU ml−1, respectively. The 2-day number of CFU per milliliter represents the first data point for Trans1. Each point shown was the result of triplicate measurements. The y-axis error bars denote standard deviations from the mean.

TABLE 1.

Incorporation of [3H]thymidine and [3H]leucine by frozen cell suspensions during 23 days of incubation at −15°Ca

| Experimental parameter | Precursor incorporation into TCA-precipitated material (dpm) |

|---|---|

| Psychrobacter sp. strain Trans1 | |

| [3H]thymidine | |

| No inhibitor | 8,500 ± 1,200 |

| 5% TCA | 4,400 ± 190 |

| + Ciprofloxacin | 4,900 ± 640 |

| + Nalidixic acid | 10,000 ± 1,600 |

| [3H]leucine | |

| No inhibitor | 5,000 ± 330 |

| 5% TCA | 3,500 ± 330 |

| + Chloramphenicol | 2,400 ± 330 |

| Arthrobacter sp. strain G200-A1 | |

| [3H]thymidine | |

| No inhibitor | 11,000 ± 300 |

| 5% TCA | 3,000 ± 290 |

| + Ciprofloxacin | 7,900 ± 170 |

| + Nalidixic acid | 22,000 ± 400 |

| [3H]leucine | |

| No inhibitor | 8,800 ± 1,300 |

| 5% TCA | 2,600 ± 170 |

| + Chloramphenicol | 3,100 ± 35 |

As indicated, 5% TCA (final concentration) or 15 μg of the antibiotic listed per ml was added to the cell suspension before the addition of radioactive precursor. The values are means ± standard deviations (n = 2).

Biochemical fractionation.

The washed, TCA-precipitated material from cells incubated at −15°C for 280 days with [3H]thymidine or [3H]leucine was fractionated according to the method of Kelley (11). This material was suspended in 30 μl of a 1:1 ethanol-ether mixture, incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 18,000 × g. The resulting supernatant was collected, and the pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of 5% TCA and incubated at 95°C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected, and the radioactivity in all fractions was quantitated by liquid scintillation counting.

In both cases, ∼50% of the [3H]thymidine was incorporated into the hot TCA extract containing nucleic acids, and ∼50% was incorporated into the insoluble residue that would contain proteins (Table 2). Although less [3H]leucine was incorporated, the majority of this precursor was incorporated into the protein fraction. Given that 7,400 to 8,400 dpm of thymidine and ∼2,100 dpm of leucine were incorporated per sample into nucleic acid and protein, respectively, it can be calculated from the specific activities of the precursors (60 to 90 Ci of [3H]thymidine and 40 to 60 Ci of [3H]leucine per mmol) and from the assumption that all cells present (1.1 × 107 CFU ml−1) (Fig. 2) participated in the DNA and protein syntheses that 4,100 to 6,900 molecules of thymidine and ∼2,000 molecules of leucine were incorporated per cell after 280 days of incubation. Based on 3-Mbp genomes and an average protein size of 36 kDa, this incorporation corresponds to replication of <1% of the genome and synthesis of ∼100 protein molecules. This incorporation is therefore insufficient for reproduction.

TABLE 2.

Fractionation of TCA-insoluble material from cell suspensions incubated at −15°C in the presence of [3H]thymidine and [3H]leucine for 280 daysa

| Macromolecular fraction (n = 2) |

Psychrobacter sp. strain Trans1

|

Arthrobacter sp. strain G200-A1

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]thymidine incorpora- tion (dpm) | [3H]leucine incorpora- tion (dpm) | [3H]thymidine incorpora- tion (dpm) | [3H]leucine incorpora- tion (dpm) | |

| Total TCA-insoluble material | 18,000 ± 650 | 3,400 ± 320 | 16,000 ± 350 | 2,600 ± 520 |

| Ethanol-ether soluble (lipid) | 930 ± 82 | 1,200 ± 280 | 1,100 ± 400 | 680 ± 180 |

| Hot 5% TCA soluble (nucleic acid) | 8,400 ± 860 | 1,800 ± 160 | 7,400 ± 26 | 1,600 ± 64 |

| Residual (protein) | 8,200 ± 1,100 | 2,100 ± 54 | 11,000 ± 1,800 | 2,100 ± 340 |

Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 2).

Implications for metabolism in glacial ice.

The results are consistent with macromolecular synthesis at −15°C by isolates recovered from polar and nonpolar glacial ice cores under conditions comparable to those within glacial ice. The 16S rDNA sequences of these psychrotrophic isolates are >99% identical to those of species recovered from brine channels in sea ice (5, 10), and therefore it was hypothesized that a biological activity at below-freezing temperatures might be exclusive to closely related strains. However, [3H]thymidine and [3H]leucine were also incorporated into TCA-precipitable material during 102 days of incubation at −15°C by a laboratory strain of E. coli, indicating that this ability is not limited to species specialized for survival in ice. For cells in 5% TCA, 3,800 ± 1,100 dpm (mean ± standard deviation) of [3H]thymidine and 4,100 ± 16 dpm of [3H]leucine were incorporated (n = 2). For cells in distilled water, 15,000 ± 470 dpm of [3H]thymidine and 17,000 ± 9,900 dpm of [3H]leucine were incorporated (n = 2).

The data reported here add to the growing body of evidence for metabolism under frozen conditions (6, 17). They support the argument that bacteria trapped in glacial ice might repair macromolecular damage that occurs while immured for extended periods. Possibly, cells remain metabolically active in solute-enriched water films on the surface of entrapped particulates and air bubbles or in liquid veins between adjacent ice crystals (15).

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to John Reeve for experimental guidance and valuable editorial comments and thank Wade Jeffrey for providing procedural advice.

This research was supported at Ohio State University by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant OPP-9714206, awarded through the Life in Extreme Environments Initiative. I am presently supported at Montana State University by NSF grant OPP-0085400.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abyzov, S. S. 1993. Microorganisms in the Antarctic ice, p. 265-295. In E. I. Friedmann (ed.), Antarctic microbiology. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Abyzov, S. S., I. N. Mitskevich, and M. N. Poglazova. 1998. Microflora of the deep glacier horizons of central Antarctica. Microbiology (Moscow) 67:66-73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldsworth, T. G., R. L. Sharman, and C. E. R. Dodd. 1999. Bacterial suicide through stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56:378-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bada, J. L., X. S. Wang, H. N. Poinar, S. Paabo, and G. O. Poinar. 1994. Amino acid racemization in amber-entombed insects: implications for DNA preservation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58:3131-3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman, J. P., S. A. McCammon, M. V. Brown, D. S. Nichols, and T. A. McMeekin. 1997. Diversity and association of psychrophilic bacteria in Antarctic sea ice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3068-3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter, E. J., S. Lin, and D. G. Capone. 2000. Bacterial activity in South Pole snow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4514-4517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christner, B. C., E. Mosley-Thompson, L. G. Thompson, V. Zagorodnov, K. Sandman, and J. N. Reeve. 2000. Recovery and identification of viable bacteria immured in glacial ice. Icarus 144:479-485. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christner, B. C. 2002. Detection, recovery, isolation, and characterization of bacteria in glacial ice and Lake Vostok accretion ice. Ph.D. thesis. The Ohio State University, Columbus.

- 9.Christner, B. C., E. Mosley-Thompson, L. G. Thompson, and J. N. Reeve. Bacterial recovery from ancient glacial ice. Environ. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Junge, K., J. J. Gosink, H. G. Hoppe, and J. T. Staley. 1998. Arthrobacter, Brachybacterium and Planococcus isolates identified from Antarctic sea ice brine. Description of Plannococcus mcceekinii, sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:306-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley, D. P. 1967. The incorporation of acetate by the chemoautotroph Thiobacillus neapolitanus strain C. Arch. Mikrobiol. 58:99-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy, M. J., S. L. Reader, and L. M. Swierczynski. 1994. Preservation records of micro-organisms: evidence of the tenacity of life. Microbiology 140:2513-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKay, C. P. 2001. The deep biosphere: lessons for planetary exploration, p. 315-327. In J. K. Fredrickson and M. Fletcher (ed.), Subsurface microbiology and biogeochemistry. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 14.Ostroumov, V. E., and C. Siegert. 1996. Exobiologial aspects of mass transfer in microzones of permafrost deposits. Adv. Space Res. 18:79-86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price, B. P. 2000. A habitat for psychrophiles in deep Antarctic ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1247-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reasoner, D. J., and E. E. Geldreich. 1985. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivkina, E. M., E. I. Friedmann, C. P. McKay, and D. A. Gilichinsky. 2000. Metabolic activity of permafrost bacteria below the freezing point. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3230-3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.