Abstract

Mycobacterium ulcerans, the etiological agent of Buruli ulcers, is an environmental pathogen. We cultivated it in an amphibian (XTC-2) cell line that grows at 28°C. By counting of Ziehl-Neelsen-stained mycobacteria and by quantitative PCR analysis, we found that M. ulcerans multiplies rapidly in association with XTC-2 cells. Transmission electron microscopy demonstrated the presence of intracellular M. ulcerans microorganisms. These data suggest an intracellular environmental niche, and we propose use of XTC-2 cells for isolation of M. ulcerans from environmental sources.

Mycobacterium ulcerans is a slowly growing mycobacterium that causes necrotizing skin ulcers, named Buruli ulcers (1, 12, 13). It is an environmental pathogen with worldwide distribution. The disease often occurs in people who live or work close to rivers and stagnant bodies of water. Emergence of Buruli ulcer in Australia and Africa has been linked to modifications of the hydric environment (11). M. ulcerans has been detected by molecular methods in stagnant water in Australia (11) as well as in aquatic African insects (F. Portaels, P. Elsen, A. Guimaraes-Peres, P. A. Fonteyne, and M. W. Meyers, Letter, Lancet 353:986, 1999), suggesting a hydric reservoir. However, M. ulcerans is cultivable from clinical material on Lowenstein-Jensen medium but has not been isolated from environmental sources so far (3). M. ulcerans is reported to be a strictly extracellular mycobacterium which grows best below 32°C. However, it is closely related to Mycobacterium marinum (3, 7), another environmental pathogen which has been recently grown in fish cells (4). The purpose of our work was to culture M. ulcerans in a poikilothermic cell line to test whether M. ulcerans can grow intracellularly at low temperatures.

Culture and kinetics in XTC2 cells.

A clinical isolate of M. ulcerans was propagated on Lowenstein Jensen medium (BioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) (6) and adjusted to 105 CFU/ml. It was aliquoted as 100 μl in tubes, which constitutes the inoculum that was used to infect XTC2 cells (average, 20 mycobacteria/cell) at 28°C as previously reported (8). Briefly, the XTC-2 cell line, derived from Xenopus laevis, was used for culture by the shell vial centrifugation technique (8). Subconfluent cells were obtained by incubating the shell vials at 28°C for 48 h after they were injected with 50,000 cells in 1 ml of Leibowitz-15 medium with l-glutamine and l-amino acids (GIBCO, Rockville, Md.), 5% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum, and 2% (vol/vol) tryptose phosphate (GIBCO). After injection of the inoculum resuspended in 0.8 ml of medium, the shell vials were centrifuged at 700 × g for 1 h at 20°C, and the supernatant was discarded. After two washings in sterile phosphate-buffered saline, 1 ml of fresh medium was added to the shell vials, which were incubated at 28°C. The cell culture medium was replaced every 7 days for up to 30 days. Cultures were sampled at days 0, 7, 15, 30, and 45.

M. ulcerans growth was evaluated by counting Ziehl-Neelsen-stained mycobacteria in serial dilutions of infected cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate. The numbers of mycobacteria were 3.7 ± 2.1 at day 0, 5.8 ± 1.7 at day 7, 10.2 ± 6.8 at day 15, 11.5 ± 5.7 at day 30, 29.6 ± 8.3 at day 45, and 35.2 ± 7 at day 60, giving an estimated doubling time of 10 days. M. ulcerans DNA was also quantified in the same cell samples using real-time PCR by the LightCycler amplification and detection system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and 0.5 pmol (final concentration) of the primers UF (5′-TGA GCT GAT CCA GGA CCA GA-3′) and UR (5′-TGG TTC CGA AGA ACT CCT TG-3′), targeting a 155-bp fragment of the M. ulcerans rpoB gene (GenBank accession number AF057491) (5); quantitative PCR amplification was carried out with 45 cycles of denaturation (8 s at 95°C), annealing (5 s at 62°C), and extension (10 s at 72°C). Serial dilutions of M. ulcerans (100 to 105 CFU/ml) in 0.01% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich Chimie, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France)-sterile phosphate-buffered saline were lysed using a French press device at 4-ton pressure and served as external standards in each run. The concentrations of mycobacterial DNA in coculture samples were calculated by comparing the cycle numbers of the logarithmic linear phase of the samples with the cycle numbers of the external standards. Noninoculated XTC-2 cells were used as a negative control. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. DNA quantification in cells gave an estimation of 5 copies/ml at day 0, 5 copies/ml at day 7, 15 copies/ml at day 15, 45 copies/ml at day 30, 70 copies/ml at day 45, and 102 copies/ml at day 60. The DNA copy kinetics is comparable to the growth kinetics measured by staining.

Intracellular detection of M. ulcerans.

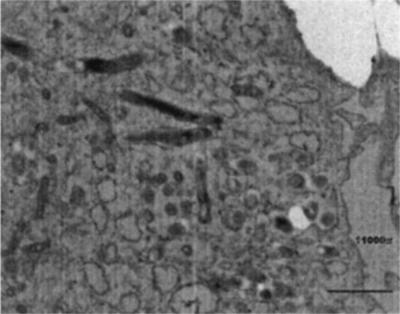

With Ziehl-Neelsen staining, the mycobacteria grown within XTC-2 cells appeared as long, purple-red and intracellular bacteria (data not shown). They were often in small clusters. For electron microscopy, harvested infected cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.1 M sucrose for 1 h at 4°C. After being washed in this buffer overnight, the cells were fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 h at room temperature and dehydrated by washing in increasing concentrations (25 to 100%) of acetone. The cells were finally embedded in Araldite (Fluka, St. Quentin Fallavier, France), and thin sections were cut with an Ultracut microtome (Reichert-Leica, Marseille, France), stained with a saturated solution of methanol-uranyl acetate and lead nitrate with sodium citrate in water, and examined in a Morgagni 268 D electron microscope (Philipps, Limeil-Brevannes, France). The mycobacteria were found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1) but never in the nucleus. Dividing mycobacteria were occasionally observed.

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy of intracellular M. ulcerans in XTC-2 cells showing a dividing mycobacterium. The bar represents 5 μm.

The above findings show that M. ulcerans is able to grow in association with XTC2 cells. It is observed intracellularly, and the medium without cells did not support the growth of M. ulcerans (data no shown). Therefore, we believe that our data demonstrate that M. ulcerans grows in XTC2 cells. A key point in our experiments was the availability of a cell line derived from a poikilothermic, amphibian vertebrate, with which we could cocultivate M. ulcerans at 28°C. This is not possible with the murine macrophage cell line J-774, which was used by Rastogi et al. (9, 10), as these cells do not survive at 28°C for more than a few days (D. Raoult, unpublished data). In their study, at 37°C, M. ulcerans caused massive lysis of macrophage-like cells as reported from histological examination of patients (13). Our data clearly indicate that M. ulcerans could be a facultative intracellular mycobacterium when grown at low temperatures. This is comparable to what is reported with M. marinum in a fish monocyte cell line (CLC cell line) cultivated at 28°C (4). These data suggest an intracellular, environmental niche for M. ulcerans.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asiedu, K., M. Scherpbier, and M. Raviglione. 2001. Ulcère de Buruli. Infection à Mycobacterium ulcerans. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 2.Chemlal, K., G. Huys, P. A. Fonteyne, V. Vincent, A. G. Lopez, L. Rigouts, J. Swings, W. M. Meyers, and F. Portaels. 2001. Evaluation of PCR-restriction profile analysis and IS2404 restriction fragment length polymorphism and amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting for identification and typing of Mycobacterium ulcerans and M. marinum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3272-3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chemlal, K., G. Huys, F. Laval, V. Vincent, C. Savage, C. Gutierrez, M. A. Laneelle, J. Swings, W. M. Meyers, M. Daffe, and F. Portaels. 2002. Characterization of an unusual mycobacterium: a possible missing link between Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium ulcerans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2370-2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Ter, S., L. Yan, and J. D. Cirillo. 2001. Fish monocytes as a model for mycobacterial host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 69:7310-7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim, B. J., S. H. Lee, M. A. Lyu, S. J. Kim, G. H. Bai, G. T. Chae, E. C. Kim, and C. Y. Cha. 1999. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB). J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metchock, B. G., F. S. Nolte, and R. J. Wallace. 1999. Mycobacterium, p. 399-437. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, C. F. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken. (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Portaels, F., L. Realini, L. Bauwens, B. Hirschel, W. M. Meyers, and W. de Meurichy. 1996. Mycobacteriosis caused by Mycobacterium genavense in birds kept in a zoo: 11-year survey. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:319-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raoult, D., B. La Scola, M. Enea, P. E. Fournier, V. Roux, F. Fenollar, M. A. M. Galvao, and X. De Lamballerie. 2001. A flea-associated Rickettsia pathogenic for humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:73-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rastogi, N., M. C. Potar, and H. L. David. 1987. Intracellular growth of pathogenic mycobacteria in the continuous murine macrophage cell-line J-774: ulstrastructure and drug-susceptibility studies. Curr. Microbiol. 16:79-92. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi, N., M. C. Blom-Potar, and H. L. David. 1989. Comparative intracellular growth of difficult-to-grow and other mycobacteria in a macrophage cell line. Acta Leprol. 7:156-159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross, B. C., J. F. Oppedisano, L. Marino, A. Sievers, T. Stinear, J. A. Hayman, M. G. Veitch, and R. M. Rogins-Browne. 1997. Detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans in environmental samples during an outbreak of ulcerative disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4135-4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stinear, T., J. K. Davies, G. A. Jenkin, F. Portaels, B. C. Ross, F. Oppedisano, M. Purcell, J. A. Hayman, and P. D. Johnson. 2000. A simple PCR method for rapid genotype analysis of Mycobacterium ulcerans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1482-1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Werf, T. S., J. W. Van der Graaf, J. W. Tappero, and K. Asiedu. 1999. Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Lancet 354:1013-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]