Abstract

The α-galactosidase gene (aga) and a gene coding for a putative transcriptional regulator from the LacI/GalR family (galR) of Lactococcus raffinolactis ATCC 43920 were cloned and sequenced. When transferred into Lactococcus lactis and Pediococcus acidilactici strains, aga modified the sugar fermentation profile of the strains from melibiose negative (Mel−) to melibiose positive (Mel+). Analysis of galA mutants of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 indicated that the putative galactose permease GalA is also needed to obtain the Mel+ phenotype. Consequently, GalA may also transport melibiose into this strain. We demonstrated that when aga was associated with the theta-type replicon of a natural L. lactis plasmid, it constituted the selectable marker of a cloning vector named pRAF800. Transcriptional analysis by reverse transcriptase PCR suggests that this vector is also suitable for gene expression. The α-galactosidase activity conferred by pRAF800 was monitored in an industrial strain grown in the presence of various carbon sources. The results indicated that the enzymatic activity was induced by galactose and melibiose, but not by glucose or lactose. The gene encoding the phage defense mechanism, AbiQ, was cloned into pRAF800, and the resulting clone (pRAF803) was transferred into an industrial L. lactis strain that became highly phage resistant. The measurements of various growth parameters indicated that cells were not affected by the presence of pRAF803. Moreover, the plasmid was highly stable in this strain even under starter production conditions. The L. raffinolactis aga gene represents the basis of a novel and convenient food-grade molecular tool for the genetic engineering of lactic acid bacteria.

Lactococcus lactis is a mesophilic lactic acid bacterium (LAB) used in starter cultures for the manufacture of several fermented dairy products, such as buttermilk, sour cream, and Cheddar cheese. Most L. lactis strains naturally contain numerous plasmids, some of them encoding phenotypes relevant to their industrial use, including lactose fermentation, proteolytic activities, and phage resistance (33). These intrinsic plasmids were used to develop an array of cloning devices adapted for the genetic engineering of lactococci. However, a good number of these devices are excluded from food applications because of the presence of antibiotic resistance genes and/or exogenous DNA.

Over the past several years, food-grade alternatives have been proposed for the genetic modification of L. lactis strains. These cloning options are based on selectable markers that can be catalogued as dominant or complementation markers (10, 16, 49). Dominant markers confer a novel phenotype that is exploited to differentiate transformed from nontransformed cells. Complementation markers require the prior development of a bacterial mutant with a specific deficiency that is later complemented by the marker to restore the original phenotype. While the limitation of dominant markers is linked to the natural occurrence of the phenotype they confer, complementation markers are inconvenient to use. Recently, a third approach was proposed that capitalizes on the advantages of both systems and relies on two components (16). The first component is a cloning vector that carries a functional lactococcal replicon entirely made up of L. lactis DNA and that has no selection marker. The second element, the “companion,” is a replication-deficient plasmid that carries an erythromycin-resistance gene as a dominant selection marker. The companion construct can only replicate in L. lactis if complemented in trans by the cloning vector. Since only the cotransformants containing both the cloning vector and the companion can survive on plates containing erythromycin, the companion can be used transiently to select cells that have acquired the cloning vector. Given its defective replication, the companion can be readily cured from the cells grown on an antibiotic-free medium after the selection step (16).

For lactococcal food-grade cloning vectors, the ability to metabolize sugars such as sucrose and lactose was previously exploited so that the sugar fermentation phenotypes could serve as dominant or complementation markers, respectively (28, 42). However, both of these phenotypes are widespread in several Lactococcus strains, which limits their utilization. Still, LAB represent an exceptional reservoir of peculiar sugar fermentation phenotypes that could potentially be exploited as selectable markers on cloning vectors used for their genetic modification. Moreover, despite the diversity of organic compounds that can collectively be metabolized by LAB, most strains and species can only grow on a limited number of substrates (29, 50). Consequently, a dominant marker based on a rare sugar fermentation phenotype emerges as an attractive option for the construction of a novel food-grade vector. For instance, melibiose (6-O-α-d-galactopyranosyl-d-glucose) is an uncommon fermentation substrate for LAB. However, melibiose fermentation is a distinctive characteristic of Lactococcus raffinolactis, a nondairy organism.

Melibiose is analogous to lactose in terms of its galactose and glucose subunits. The difference resides in the chemical link between the two subunits. While lactose has a β-1-4 glycosidic bond that can be enzymatically hydrolyzed by a β-galactosidase, melibiose displays an α-1-6 glycosidic bond that can be broken down by an α-galactosidase. The monosaccharide subunits resulting from the intracellular hydrolysis of these sugars are subsequently degraded through metabolic pathways found in a wide variety of LAB. Consequently, α-galactosidase is a key enzyme in melibiose fermentation.

The exploitation of α-galactosidase activity has recently emerged in biotechnology for yeast research. A few strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae possess a mel gene coding for an α-galactosidase and are capable of assimilating the melibiose released from the hydrolysis of raffinose (molasses sugar) by the enzyme invertase (38). Baker's yeast strains able to utilize melibiose by expressing the mel1 gene have been constructed to improve the overall yield of either biomass or ethanol production from molasses, thereby reducing the biological oxygen demand of industrial waste (40, 45, 52). The yeast mel1 gene, which encodes α-galactosidase, a secreted but largely cell-wall-associated enzyme (27), is also used as a reporter gene in the yeast two-hybrid system (1). In this particular system, the extracellular localization of the α-galactosidase is considered an advantageous characteristic for whole-cell enzymatic assays and sensitive screening of living cells on X-α-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside) indicator plates (1).

In this study, we describe the cloning and sequencing of the α-galactosidase gene from L. raffinolactis ATCC 43920, the isolation of a theta-replicon from an L. lactis plasmid, and their association to create a novel cloning vector for food-grade applications in lactococci and other LAB.

(Parts of this work were presented at the 101st General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Orlando, Fla., and at the 96th Annual Meeting of the American Dairy Science Association, Indianapolis, Ind.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli was grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB), Lactococcus was grown at 30°C, and Streptococcus thermophilus was grown at 42°C in M17 broth (Quélab, Montréal, Québec, Canada; and Difco, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with the appropriate sugar. Pediococcus acidilactici was grown in MRS medium (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 37°C. Carbohydrate fermentation was tested in BCP medium (2% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.4% NaCl, 0.15% Na-acetate, 40 mg of purple bromocresol per liter). Enrichment of Mel+ transformants was usually performed in liquid EL1 medium (1% tryptone, 0.4% NaCl, 0.15% Na-acetate, 40 mg of purple bromocresol per liter). Sugars were filter sterilized and added to autoclaved medium at a final concentration of 0.5%. The BCP and EL1 formulations were based on the Elliker medium (13). When required, antibiotics were added at 50 μg of ampicillin per ml for E. coli and 5 μg of erythromycin or chloramphenicol per ml for L. lactis. All of the antibiotics were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Phages were amplified on their respective L. lactis hosts as described previously (15).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | supE44 Δlac U169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Invitrogen Life Technologies |

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | ||

| MG1363 | Laboratory strain, plasmid free, Mel− | 18 |

| SMQ-741 | Industrial strain, Mel− | QI |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis | ||

| IL1403 | Laboratory strain, plasmid free, Mel− | 7 |

| SMQ-561 | Industrial strain, Mel− | QI |

| Lactococcus raffinolactis ATCC 43920 | Plasmid free, Mel+ | ATCC |

| Streptococcus thermophilus SMQ-301 | Industrial strain, Mel− | 51 |

| Pediococcus acidilactici SMQ-249 | Industrial strain, Mel− | QI |

| Phages | ||

| c2 | c2 species, infects L. lactis MG1363 | 23 |

| p2 | 936 species, infects L. lactis MG1363 | 37 |

| Q37 | 936 species, infects L. lactis SMQ-741 | 35 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBS | Cloning vector for DNA sequencing, Apr | Stratagene |

| pGhost4 | Integration vector, Ts Emr | 31 |

| pNC1 | Replicon-screening vector, Apr Cmr | 16 |

| pNZ123 | Shuttle cloning vector, Cmr | 9 |

| pTRKH2 | Shuttle cloning vector, Emr | 41 |

| pGalA2 | pGhost4 + L. lactis MG1363 truncated galA, Ts Emr | This study |

| pGalA3 | pTRKH2 + L. lactis MG1363 galA, Emr | This study |

| pRAF100 | pBS + 4-kb EcoRI/HindIII fragment of L. raffinolactis ATCC 43920 encoding aga, Apr | This study |

| pRAF300 | pNZ123 + 4-kb fragment of pRAF100 | This study |

| pRAF301 | pNZ123 + 2.5-kb aga amplicon from L. raffinolactis ATCC43920 | This study |

| pRAF800 | Food-grade cloning vector, Mel+ | This study |

| pRAF803 | pRAF800 containing abiQ, AbiQ+ | This study |

| pSRQ800 | Natural L. lactis plasmid, AbiK+ | 3, 15 |

| pSRQ835 | pNCl + replicon of pSRQ800 | This study |

| pSRQ900 | Natural L. lactis plasmid, AbiQ+ | 3, 14 |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Emr, erythromycin resistance; Mel, melibiose fermentation; Abi, phage abortive infection mechanism; Ts, thermosensitive replicon.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; QI, Quest International, Rochester, Minn.

DNA techniques.

Routine DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard procedures (46). Restriction enzymes, alkaline phosphatase, RNase-free DNase, RNase inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Québec, Canada), and T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) were used according to the supplier's instructions. All primers were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies. Transformation of E. coli (46), L. lactis (24), S. thermophilus (24), and P. acidilactici (6) was performed as described elsewhere. Unless specified otherwise, plasmid DNA from E. coli and L. lactis was isolated as previously described (16). L. raffinolactis total DNA was isolated from a culture grown overnight at 30°C in 200 ml of GM17. Pelleted cells were resuspended in 10 ml of lysis solution (6.7% sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 30 mg of lysozyme per ml) and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Following the addition of 1.12 ml of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), the mixture was kept at 60°C for 10 min. After addition of 80 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml; Roche Diagnostics), the lysate was incubated at 60°C for an additional 20 min. After three phenol-chloroform (1:1) extractions, the DNA was precipitated with a 1/10 volume of 3 M potassium acetate (pH 7.0) and 2 volumes of 95% ethanol. The DNA precipitate was washed with 70% ethanol, air dried, and dissolved in 1 ml of sterile double-distilled water containing RNase A (5 μg/ml).

Cloning and sequencing of aga from L. raffinolactis.

The oligonucleotide α-gal (Table 2) was used as a probe in Southern hybridizations to locate the α-galactosidase gene on specific restriction fragments of the L. raffinolactis chromosome. The probe was labeled with the digoxigenin 3′-end oligonucleotide labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics). Prehybridization, hybridization, posthybridization washes, and detection by chemiluminescence were performed as suggested by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics). Genomic DNA was double digested with HindIII and EcoRI, and restriction fragments of 3 to 5 kb were extracted from 0.8% agarose gel after electrophoresis. DNA was recovered from the gel as described by Duplessis and Moineau (11). Relevant DNA fragments were cloned into pBS (HindIII-EcoRI), and recombinants were selected by blue-white screening and restriction mapping as described elsewhere (46). The DNA sequences were determined on both strands with universal primers and the Tn1000 kit (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, Mo.). E. coli plasmid DNA was isolated with the Qiagen Plasmid Maxi kit (Chatsworth, Calif.). DNA sequencing was carried out by the DNA sequencing service at the Université Laval with an ABI Prism 3100 apparatus. Sequence analyses were performed by using the Wisconsin Package software (version 10.2) of the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) (8).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|

| α-gal | TTTGTTYTWGATGATGGWTTGTTTGGW |

| abiQ1 | TCTAGATCTAGAACCCGTCCAAGGAATATACAA |

| abiQ2 | TCTAGATCTAGATGTTTCTAATCTAAATGACTGGT |

| galA5 | TCTAGATCTAGACAAGGTCGCTCTGATATTAG |

| galA6 | GAATTCGAATTCGATCATGTCCTAGTGCACCA |

| galA7 | GAATTCGAATTCCTTTGTAGTCCCAGCGGTCT |

| galA8 | CTCGAGCTCGAGCCAATCAACAATGCGAGCTC |

| IB800.6 | ACATGACGATACCGCTACA |

| IB800.8 | AATGCAAAAGACCGCTCTCA |

| IB800.21 | TCTAGATCTAGAAGGGCTTGCCCTGACCGTCT |

| IB800.23 | CTCGAGCTCGAGTTACACCTAACTCATCCGCA |

| raf12 | TCTAGATCTAGAAGGGCTTGCCCTGACCGTCT |

| raf13 | CTCGAGCTCGAGCCATCACCGAAGAGGGCTGT |

| raf39 | ATGAGTACCTCTCGTGACCA |

| raf56 | GCTGGGATTAATCCCTTTGG |

| raf63 | GAATTCGAATTCGTCTGTCGGTCTTCAATATC |

| Forward | CGCTATTACGCCAGCTGGCGAAA |

| Reverse | TAGGCACCCCAGGCTTTACACTT |

Underlines indicate nucleotides participating in restriction sites.

Construction of a L. lactis MG1363 galA mutant.

Two primer sets (Table 2) carrying terminal restriction sites were used to amplify by PCR the DNA regions upstream (galA5-galA6) and downstream (galA7-galA8) from galA of L. lactis MG1363. Both amplicons were digested with EcoRI, ligated together with T4 DNA ligase, and reamplified by PCR with primers galA5 and galA8. The resulting amplicon was digested with XbaI and XhoI and cloned into pGhost4 to generate pGalA2. Homologous integration of pGalA2 into the chromosome of L. lactis MG1363 was achieved at 37°C in the presence of erythromycin as described previously (31). A pGalA2 integrant was selected and grown at 30°C without selective pressure to favor excision and loss of the plasmid. Colonies were screened for erythromycin sensitivity, and the presence of the mutated allele was confirmed by PCR with primers galA5 and galA8. For the complementation assay, the wild-type galA gene was amplified by PCR from MG1363 with primers galA5 and galA8, and the PCR product was cloned into pTRKH2 to construct pGalA3. The sugar fermentation pattern was determined on API 50 CH strips with API 50 CHL medium (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Isolation of the minimal replicon of three L. lactis plasmids.

L. lactis plasmid pSRQ800 (3) was subcloned into the vector pNC1, which can replicate in E. coli, but not in L. lactis. A double-stranded nested deletion kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d'Urfé, Québec, Canada) was used to generate several deleted clones. These deletants were tested for their ability to replicate in L. lactis. The smallest replicative deletant was sequenced on both strands.

Construction of a food-grade vector.

The minimal replicon of pSRQ800 was amplified by PCR with the primers IB800.21 and IB800.23 (Table 2) and with pSRQ800 as the template. The aga gene from L. raffinolactis was also amplified by PCR with the primers raf12 and raf13 and with L. raffinolactis total DNA as the template. The two PCR products were digested with XbaI and XhoI and joined together, and the ligation mixture was used directly to transform L. lactis MG1363 by electroporation. Cells were incubated for 2 h for recuperation in SM17MC medium (24) supplemented with 0.5% melibiose. After recuperation, electroporated cells were inoculated into 10 ml of Mel-EL1 medium and incubated at room temperature until acidification (which might take a few days), which was manifested by a color change (from purple to yellow) of the pH indicator purple bromocresol. Then, cells were diluted in sterile peptonized water, plated on Mel-BCP plates, and incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Plasmid DNA was recovered from the Mel+ (yellow) colonies and sequenced.

Expression profile of pRAF800.

The transcription profiles of aga (α-galactosidase) and repB (plasmid replication initiator) encoded on pRAF800 were determined by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). L. lactis was grown at 30°C in 10 ml of M17 broth supplemented with 0.5% melibiose to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2. The culture was pelleted, and cell lysis was carried out in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE) containing 30 mg of lysozyme per ml (Elbex, Québec, Canada) at 37°C for 10 min. Total RNA was isolated by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer. The DNA was eliminated from the isolated RNA by using RNase-free DNase in the presence of RNase inhibitor. Then, an additional RNeasy column was used for RNA cleanup. All of the reagents (RNA, RT buffer, dithiothreitol [DTT], deoxynucleoside triphosphates [dNTP], hexanucleotides, and RNase inhibitor), except RT for the cDNA synthesis, were mixed in microtubes. RNase-free DNase was added to the mixture for a second DNase treatment at 37°C for 30 min. The DNase was heat inactivated at 75°C (5 min), and tubes were cooled to 4°C. Expand RT (Roche Diagnostics) was added, and cDNA synthesis was performed essentially as recommended by the manufacturer. Two microliters of the cDNA was used for PCR amplification with various primer combinations. The PCR products were fractionated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV illumination with a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

α-Galactosidase assay.

Strains were grown in 10 ml of M17 broth supplemented with 0.5% of the appropriate sugar to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6. Cell pellets were washed twice in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) and resuspended in 500 μl of the same buffer. Cells were disrupted at 4°C by shaking three times on a vortex (3 min each time followed by a 1-min rest on ice) in the presence of glass beads (106 μm in diameter and finer [Sigma]). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant (cell extract) was kept on ice until the enzymatic assay, which was completed within 2 h. The protein concentration was estimated by using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay reagent. The α-galactosidase activity was assayed at 30°C and at pH 7.0 with p-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (PNPG) as a substrate (32). Essentially, 50 or 100 μl of cell extract was added to the prewarmed reaction mixture containing 250 μl of 3 mg of PNPG per ml (Sigma) and enough NaPO4 (50 mM at pH 7.0) to complete the volume to 3 ml. Aliquots of 900 μl were retrieved after 5, 10, and 15 min of incubation and added to 100 μl of chilled 1 M Na2CO3. The OD420 was determined with a Beckman DU530 spectrophotometer, and activity was calculated by using the extinction coefficient for PNPG at 420 nm of 18,300 M−1 cm−1.

Cloning of abiQ into pRAF800.

The phage resistance gene abiQ (14) was amplified by PCR with the primers abiQ1 and abiQ2 and with pSRQ900 as the template. pRAF800 was digested with XbaI, dephosphorylated, and ligated to the XbaI-digested abiQ amplicon. The ligation mixture was used to transform L. lactis MG1363 by electroporation, and Mel+ transformants were obtained as indicated above. Resistance to phages c2 and p2 was assessed as described previously (36).

Evaluation of the effect of pRAF803 on the growth rate of an industrial L. lactis strain.

Stock cultures of L. lactis strains SMQ-741 and SMQ-741 (pRAF803) were prepared by mixing 10 ml of a fresh culture with 25 ml of 20% skim milk and 25 ml of a 20% glycerol solution and then freezing the mixture at −70°C in 1-ml sterile cryovials (Nalgene, Rochester, N.Y.). Working cultures were prepared by inoculating 100 ml of LM17 broth with 1 ml of a thawed stock culture, and incubating this mixture at 30°C for 24 h. The growth of L. lactis strains in LM17 broth was evaluated by automated spectrophotometry with a Powerwave unit (Bio-Tek Instrument, Winooski, Vt.) as described previously (4). Media were prepared in test tubes, inoculated at 1% (vol/vol) from a fresh 100-ml LM17 working culture, and 200-μl samples were added aseptically to each well. Microplates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h. The OD600 of each well was automatically recorded every 15 min. Prior to each reading, the plates were shaken at intensity setting 2 for 3 s.

Starter production in milk and in commercial medium.

Starter production was achieved in either 6% (wt/wt) nonfat dry milk or in 6-Cess Plus medium (SKW Biosystems-Canada, Mississauga, Canada). Fermentations in milk were carried out without an external pH control, while a pH control was used in fermentations in 6-Cess Plus medium. All media were heat pasteurized at 90°C for 45 min. Two liters of media was inoculated at 1% (vol/vol) from a fresh LM17 culture. Production was carried out at 30°C in 2.5-liter New Brunswick Bioflo 3000 units (New Brunswick, Edison, N.J.). Agitation was kept at 60 rpm, except during addition of base (100 rpm). To reproduce industrial conditions, the pH-controlled fermentation was carried out by zone neutralization. In such a process, acidification is allowed to proceed until a pH of 5.8 is reached. At this pH set point, agitation is increased to 100 rpm, and base is added until a pH of 6.0 is attained. At this second pH set point, base addition is stopped and agitation is lowered to 60 rpm. If acidification continued, the cycle is reinitiated once the pH reaches 5.8. The neutralizing base was composed of a 5:1 mixture of 6 M KOH and 6 M NH4OH. Fermentations performed with the pH control were stopped when the medium's sugar was depleted (e.g., when acidification stopped). In milk, fermentations were stopped when the pH of the medium reached 4.7. The time required to complete the various fermentations was registered and will be referred to hereafter as the “fermentation time.”

Biomass production and acidification activity of the starters produced in milk or in commercial medium.

Viable counts of the starters were obtained by plating appropriate dilutions (0.1% sterile peptone) on LM17 agar. The first dilution bottle contained approximately 2.5 g of glass beads in order to break cell chains. A modified Pearce test was used to determine the acidification activity of the starters (5). First, the milk powder was irradiated at 5 kG. Five hundred milliliters of 10% reconstituted nonfat dry milk was prepared. Milk solutions were kept for 16 h at 4°C prior to use. Tubes containing milk were inoculated at 1% (vol/vol) with samples taken at the end of starter production fermentations and incubated at 32°C for 5 h. A pH reading was made at the end of the incubation period. Three independent assays were carried out for each experiment.

Evaluation of the stability of pRAF803.

The stability of pRAF803 was evaluated as the percentage of cells in the starter expressing the melibiose fermentation or phage resistance phenotypes conferred by the plasmid. Starter samples were streaked on LM17 plates and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. For each sample, melibiose fermentation was tested for 100 isolated colonies on Mel-BCP plates. Mel− colonies were reinoculated on Mel-BCP plates and tested for phage resistance. Resistance to phage Q37 was also tested for another 100 isolated colonies as described elsewhere (36). Phage-sensitive colonies were tested again for phage resistance and for melibiose fermentation.

Accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers assigned to the nucleotide sequences of Lactococcus plasmids pSRQ800 and pRAF800 are U35629 and AY091640, respectively.

RESULTS

Characterization of the α-galactosidase locus of L. raffinolactis.

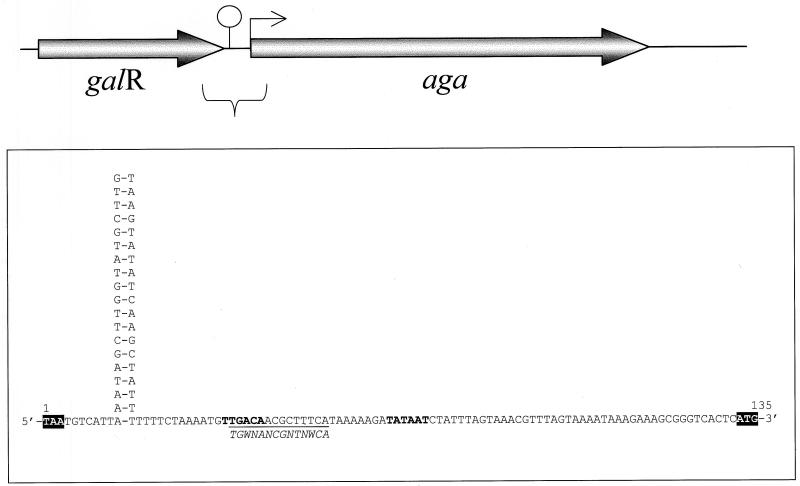

A stretch of conserved amino acids (FVLDDGWFG) was identified within bacterial α-galactosidases and used to design a degenerated oligonucleotide primer (α-gal, Table 2), based on lactococcal codon preference. Using this primer as a probe in Southern hybridization assays, the α-galactosidase gene was located on a 4-kb EcoRI-HindIII DNA fragment of L. raffinolactis ATCC 43920 (data not shown). This fragment was cloned into pBS (pRAF100), sequenced, and found to comprise two genes, galR and aga (Fig. 1). Based on amino acid sequence similarities and conserved motifs, these two genes likely encode an α-galactosidase (Aga, 735 amino acids) and a transcriptional regulator (GalR, 245 amino acids) from the LacI/GalR family. The product of aga displays up to 54% identity with bacterial α-galactosidases, particularly Geobacillus stearothermophilus AgaN (390 identical amino acids out of 722), AgaB (376 of 730 amino acids), and AgaA (372 of 730 amino acids) (GenBank accession no. AAD23585.1, AAG49421.1, and AAG49420.1, respectively). GalR is up to 34% identical to various transcriptional regulators, including those of the galactose operon from Lactobacillus casei (115 of 343 amino acids), Streptococcus thermophilus (112 of 340 amino acids), and Streptococcus salivarius (109 of 348 amino acids) (GenBank accession no. AAC19331.1, AAD00092.1, and AAL67295, respectively). An inverted repeat with the potential to form a stem-loop structure was found in the galR-aga intergenic region and could act as an intrinsic terminator. A canonical promoter sequence (TTGACA-N17-TATAAT) was found upstream of aga and a putative catabolite-responsive element (CRE), involved in the regulation of sugar metabolism (25), overlaps the −35 region. Consequently, the expression of aga is likely regulated through catabolite repression in L. raffinolactis.

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the aga locus of L. raffinolactis. Genes are identified by shaded arrows oriented to indicate the direction of transcription. The gene aga codes for α-galactosidase, while the gene galR codes for a putative transcriptional regulator. The putative terminator is indicated by a stem-loop structure, and the putative promoter is indicated by an arrow upstream of aga. The sequence of the galR-aga intergenic region is presented in the box. The GalR stop codon and the Aga start codon are shaded in black. The −35 and −10 regions of the promoter are indicated in boldface. The CRE sequence is underlined. The consensus CRE sequence for gram-positive bacteria is presented in italic below the underline.

Cloning of aga in L. lactis.

The 4-kb DNA fragment from L. raffinolactis was cloned into the lactococcal cloning vector pNZ123 (pRAF300) and transferred by electroporation into the laboratory strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. The presence of pRAF300 gave L. lactis MG1363 the ability to ferment melibiose. This phenotype was easily observable on BCP plates containing melibiose, because the acidification resulting from melibiose fermentation led to the formation of yellow colonies surrounded by a yellow halo on the purple background. On this medium, melibiose-negative cells formed smaller purple colonies. A 2.5-kb fragment containing only the aga gene and its putative promoter was also amplified by PCR, cloned into pNZ123 (pRAF301), and transferred into the following five strains: L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363, L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 and SMQ-561, Streptococcus thermophilus SMQ-301, and Pediococcus acidilactici SMQ-249. The presence of pRAF301 was sufficient to give the melibiose fermentation phenotype to all strains except S. thermophilus.

Identification of the melibiose carrier in L. lactis.

L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 has a limited sugar fermentation pattern, including acid production from galactose. Because different galactosides can be imported by the same transporter (43), we hypothesized that the putative permease of galactose GalA (21) might also transport melibiose into L. lactis MG1363. Using the suicide vector pGalA2 (see Materials and Methods for details), a galA-deficient mutant (ΔgalA) of L. lactis MG1363 was constructed by double crossover. After two homologous recombination events, 11 of the 24 Ems clones tested contained a 600-bp truncated copy of galA instead of the 2-kb wild-type allele. Surprisingly, all of the ΔgalA mutants conserved their ability to produce acid from galactose (Table 3). No difference between the sugar fermentation patterns of the wild-type and ΔgalA L. lactis strains was observed on API 50 CH strips. One of the ΔgalA mutants was selected and transformed with pRAF300. The 50 Cmr transformants tested did not ferment melibiose (Table 3). The wild-type galA gene cloned into the cloning vector pTRKH2 (pGalA3) was then introduced into the L. lactis strain MG1363(ΔgalA, pRAF300) to complement the mutation. All 24 Emr Cmr transformants tested were able to produce acid from melibiose, indicating that galA is required to obtain the Mel+ phenotype provided by aga (Table 3). All of the transformants generated above, such as MG1363(ΔgalA), MG1363(ΔgalA, pRAF300), and MG1363(ΔgalA, pRAF300, pGalA3), were confirmed by plasmid profile (data not shown), PCR amplification of aga and ΔgalA (data not shown), and their sensitivity to phages c2 (c2 species) and p2 (936 species).

TABLE 3.

Galactose and melibiose fermentation phenotypes of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 derivatives used in this study according to their genotype

| Genotypea | Phenotype |

|---|---|

| galA | Gal+ Mel− |

| galA aga | Gal+ Mel+ |

| ΔgalA | Gal+ Mel− |

| aga ΔgalA | Gal+ Mel− |

| galA* aga ΔgalA | Gal+ Mel+ |

∗, supplemented in trans.

Isolation of lactococcal plasmid replicons.

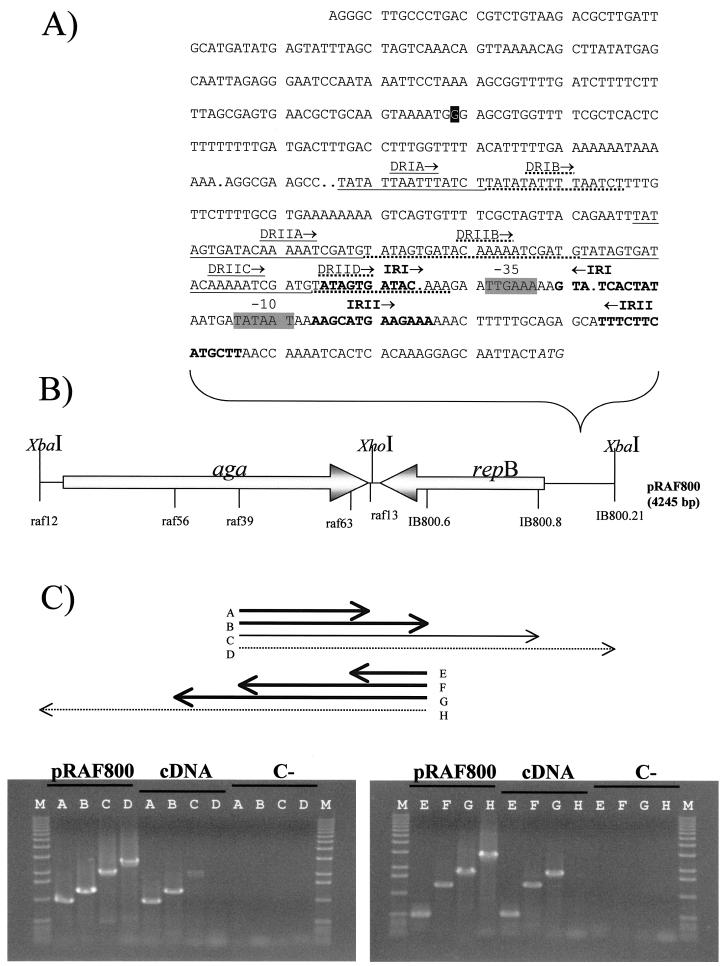

The minimal region essential for the maintenance of the natural lactococcal plasmid pSRQ800 was identified by carrying out successive deletions and sequence analysis. The minimal DNA segment consisted of a typical lactococcal theta replication module containing a replication origin (repA) and the gene encoding a replication initiator (repB). The replication origin includes the AT-rich stretch, iterons (22-bp direct repeats), and inverted repeats usually found in other lactococcal plasmids (Fig. 2A). The minimal region obtained by nested deletion that still allowed plasmid replication was 2,212 bp. This region encompassed positions 7196 through 1549 in the plasmid sequence (3). The replicon was further limited (1,767 bp) by PCR to positions −443 to +44 from the repB coding sequence to serve as the basis for a new plasmid vector.

FIG. 2.

Genetic organization of pRAF800. (A) Sequence of the replication origin of pRAF800. The replicon of the L. lactis plasmid pSRQ800 was used to construct pRAF800. The nucleotide boxed in black differs from pSRQ800 (T→G substitution). Direct repeats (DR) are underlined (continuous and discontinuous). Inverted repeats (IR) are indicated in boldface. The putative −35 and −10 boxes of the repB promoter are shaded. The repB start codon is italicized. (B) Map of pRAF800. Genes are identified by shaded arrows oriented to indicate the direction of transcription. aga, gene encoding α-galactosidase; repB, gene encoding the replication initiator protein. The positions of primers used for RT-PCR are indicated on the plasmid map. bp, base pairs. (C) Expression profile of pRAF800. RNA was isolated from SMQ-741 cells transformed with pRAF800 and grown in the presence of melibiose. RT-PCR was used to map the 3′ ends of aga and repB transcripts. PCR products were obtained with an mRNA internal primer as well as one of four possible 3′-end primers. Amplicons were separated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The targeted transcripts are identified by arrows A to H (indicating the direction of transcription), as seen on the gels. PCR products are aligned with their corresponding start and stop positions on the plasmid map. Bold line, transcript detected; normal line, transcript weakly detected; dotted line, transcript not detected. M, 1-kb DNA ladder (Invitrogen Life Technologies).

Construction of a food-grade vector.

The aga gene of L. raffinolactis with its putative promoter and the minimal replicon of L. lactis plasmid pSRQ800 were amplified by PCR and ligated together to form a functional vector with two cloning sites (XhoI and XbaI). The ligation mixture was transferred by electroporation into L. lactis MG1363, and after 4 days of enrichment by incubation at room temperature in liquid EL1 medium containing melibiose, Mel+ transformants were recovered on BCP plates. Plasmid DNA of a Mel+ transformant was isolated, digested, analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and sequenced on both strands. The 4,245-bp constructed plasmid was named pRAF800 (Fig. 2B). This novel plasmid differed from the two parental DNA segments in four locations. The first difference is a nonconservative A/G substitution causing a T/A amino acid change at position 227 of the α-galactosidase enzyme. A second A/G substitution is found at position 2424, immediately downstream of the aga coding sequence. A single-nucleotide deletion was also found within the primer raf13 sequence, suggesting a likely error in the primer sequence itself. Finally, a T/G substitution is localized 358 nucleotides upstream of the repB start codon, in the replication origin region (Fig. 2A). These variations, which most likely resulted from PCR amplification, did not affect the functionality of the plasmid.

Expression profile of pRAF800 in the industrial strain SMQ-741.

To determine the vector-driven transcriptional activity at the two proposed cloning sites (XbaI and XhoI) of pRAF800, the 3′ ends of aga and repB transcripts were determined by RT-PCR with RNA isolated from L. lactis SMQ-741(pRAF800). Two overlapping transcripts were detected (Fig. 2C). The repB transcript overlaps most of the aga sequence and likely ends at the inverted repeat located immediately upstream of aga (Fig. 1). The aga transcript also extends beyond repB and is suspected to end at one of the multiple inverted repeats located within this gene, as shown by the weak signal obtained with primer IB800.8. These findings suggest that the XhoI site region is transcribed in both directions from the two promoters of aga and repB. Moreover, the XbaI site region does not appear to be transcribed from either of the two promoters located on pRAF800.

α-Galactosidase activity in L. lactis.

The activity of α-galactosidase was measured in cell extracts from L. lactis SMQ-741(pRAF800) after growth at 30°C in the presence of various sugars (Table 4). Activity was measured under conditions in which the rate of reaction was constant with the time of incubation and proportional with the enzyme concentration. The results, summarized in Table 4, indicate that the α-galactosidase activity was four- to fivefold higher in galactose- and melibiose-grown cells than in glucose- or lactose-grown cells. Because no α-galactosidase activity could be detected with the parental strain SMQ-741, aga is clearly responsible for this activity in L. lactis.

TABLE 4.

α-Galactosidase activity in L. lactis SMQ-741 transformed with pRAF800 and grown in the presence of various sugars

| Sugar | Activity (nmol of p-nitrophenol formed/mg of protein/min)a |

|---|---|

| Glucose | 83.0 ± 18.0 |

| Galactose | 368.3 ± 30.3 |

| Lactose | 75.3 ± 17.2 |

| Melibiose | 441.1 ± 35.1 |

Values are the means ± standard deviations of 12 measurements performed with two cell extract quantities in two independent experiments. Note that no α-galactosidase activity was detected in the parental strain, SMQ-741.

Cloning of a phage resistance mechanism into pRAF800 and its transfer into an industrial L. lactis strain.

To test the effectiveness of the novel cloning tool, the gene encoding the phage abortive infection mechanism, AbiQ (14), was cloned into pRAF800 at one of the two cloning sites available. The phage resistance determinant was obtained by a PCR amplification from pSRQ900 and inserted into the unique XbaI site of pRAF800 to generate pRAF803. The recombinant vector was first obtained in L. lactis MG1363. All 48 Mel+ colonies tested were resistant to phages c2 and p2. Plasmids pRAF800 and pRAF803 were then transferred by electroporation into the industrial L. lactis subsp. cremoris strain SMQ-741. Because this strain did not grow well in the EL1 medium, the posttransformation enrichment was performed in liquid BCP medium containing melibiose. All Mel+ colonies tested contained pRAF803 and were resistant to phage Q37 (936 species), while Mel− colonies did not contain pRAF803 and were sensitive to phage Q37.

Effect of pRAF803 on various growth parameters of the industrial L. lactis strain SMQ-741 and evaluation of its stability.

The growth of L. lactis strain SMQ-741 was compared to that of its derivative carrying pRAF803 (Table 5). First, the growth rates of both strains were evaluated in LM17 broth, and no significant difference was observed. Then, both strains were produced in fermentation units by using milk or a commercial medium. The presence of pRAF803 did not disturb the starter production process in terms of fermentation time and biomass production (Table 5). The acidification activities of these starters were also tested in milk, and they were found equivalent for the two strains (Table 5). Finally, the prevalence of pRAF803 was measured after starter production. Over 95% of the cells displayed both of the pRAF803-encoded phenotypes, indicating that pRAF803 was very stable (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Effect of pRAF803 on various growth parameters of L. lactis strain SMQ-741 and its stability under starter production conditions

| Strain | Growth rate (h−1)a | Fermentation time (h)b

|

Biomass production (108 CFU/ml)b

|

Acidification activity (pH)b

|

Plasmid stability (%)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | Commercial medium | Milk | Commercial medium | Milk | Commercial medium | Milk | Commercial medium | ||

| SMQ-741 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 16.3 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.0 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | NAc | NA |

| SMQ-741 (pRAF803) | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 9.0 ± 0.0 | 17.3 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 7.7 ± 1.5 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 97.5 ± 1.8 | 97.9 ± 1.5 |

Values are the means of two independent trials ± standard deviations.

Values are the means of three independent trials ± standard deviations.

NA, not applicable.

DISCUSSION

α-Galactoside metabolism was chosen as a potential selectable marker for the development of a novel food-grade cloning vector, because it is rarely found in lactococci and in many LAB. Given its relatedness to food-grade bacteria, its nonpathogenicity, and its α-galactosidase activity, L. raffinolactis was selected as the source of the aga gene. Typically, strains of L. raffinolactis can be isolated from raw milk, various animals, and ready-to-eat foods (2, 44, 47). The genetic determinant of the α-galactosidase was located on a 4-kb chromosome fragment of L. raffinolactis. On the basis of protein similarities and of conserved motifs, functions were attributed to the two open reading frames found on this sequenced DNA segment, aga and galR. When transferred into various lactococci and Pediococcus strains, the aga gene gave them the ability to produce acid from the disaccharide melibiose. This disaccharide is not prevalent in the environment and is not a common fermentation substrate for lactococci. Thus, the Mel+ phenotype was regarded as a prospective dominant selection marker for a plasmid vector.

To be able to metabolize melibiose, cells require, in addition to α-galactosidase, a transporter to allow the sugar to reach the bacterial cytoplasm. The proposed permease GalA from the galactose operon (21) was suspected to act as the nonspecific carrier of melibiose in L. lactis MG1363. Inactivation of galA resulted in a loss of the Mel+ phenotype. This altered phenotype could be complemented and restored by plasmid-encoded GalA. Accordingly, GalA can now be regarded as the melibiose transporter in L. lactis MG1363. Surprisingly, galA inactivation did not visibly affect the capacity of MG1363 cells to produce acid from galactose. Thus, the exact role of the encoded transporter in the galactose fermentation phenotype remains to be elucidated.

In addition to a selectable marker, a plasmid-cloning vector requires a replicon to support its autonomous replication as well as its maintenance in a bacterial host. Because lactococcal plasmids containing a theta-type replicon are well known for their structural and segregational stability and their narrow host range, a vector using this mode of replication should be carried in a stable manner in lactococci with limited risk of heterologous transfer (12, 16, 19, 26, 30, 48, 53). The lactococcal plasmid pSRQ800 was selected as the source of theta replicon, because it is found in some L. lactis strains currently utilized in large-scale industrial milk fermentation and has a history of safe use (34). The minimal theta replicon of pSRQ800, obtained through the functional analysis of successive deletions, included two genetic features: a noncoding region (repA) and a coding region (repB) containing the replication initiator gene. The replicon of pSRQ800 was used for the construction of pRAF800.

To test this novel food-grade vector, the phage resistance mechanism AbiQ was cloned into pRAF800, and the resulting construct was successfully transferred into a phage-sensitive industrial L. lactis strain that became phage resistant. The pRAF800 derivatives coexisted with the wild-type plasmids of L. lactis SMQ-741, a finding that is consistent with previous studies (16, 17, 20, 22, 48). However, replicon homology is also recognized as the major cause of plasmid incompatibility that excludes coexistence (20, 39). Although this phenomenon was not observed in this study, plasmid incompatibility is likely to occur with other L. lactis strains. The replacement of the pSRQ800 theta replicon with those of other lactococcal plasmids could be an alternative to circumvent incompatibility.

Transcription profiling of the 3′ ends of aga and repB transcripts indicated that the genetic determinants of pRAF800 were expressed on two overlapping and divergently oriented transcripts. Thus, one of the proposed cloning sites (XhoI) offers the opportunity to express cloned genes from one of either plasmid-localized promoters, one of which is inducible by carbohydrates, such as galactose and melibiose. The other cloning site (XbaI) appears to be adapted for the expression of genes from their own promoters. If needed, future versions of pRAF800 could carry features such as multiple cloning sites and a transcriptional terminator at the XhoI site, to avoid the production of an antisense RNA that could interfere with gene expression. Moreover, the analysis of α-galactosidase activity provided by pRAF800 in SMQ-741 indicated that lactose and glucose did not induce the enzyme activity. Since lactose is present in the industrial conditions of starter culture production and milk fermentation, the presence of pRAF800 in an industrial L. lactis strain should not cause a metabolic burden. In fact, growth of L. lactis SMQ-741 was clearly not affected by the presence of pRAF803, as evaluated with four independent parameters. Moreover, the plasmid was found to be stable under conditions similar to those in industrial starter productions. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of the applicability of a food-grade plasmid vector for industrial purposes.

In conclusion, a novel small plasmid vector was constructed based on an L. lactis theta replication module and an L. raffinolactis aga gene encoding α-galactosidase as a selection marker. Constituted exclusively of lactococcal DNA and exempt from antibiotic resistance genes, the proposed vector should therefore be appropriate for safe use in foods. The Mel+ phenotype produced by the L. raffinolactis aga gene emerged as a convenient dominant selection marker operating with a practical melibiose-containing medium. Lactococcal α-galactosidases represent new molecular tools for the genetic modification of lactococci and other LAB that could be exploited for research purposes and as food-related applications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Quest International for providing the industrial strains and to Farah-Michèle Manigat for technical assistance.

We thank the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Research Partnerships Program-Research Network on Lactic Acid Bacteria), Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Novalait, Inc., Dairy Farmers of Canada, and Institut Rosell-Lallemand, Inc., for financial support. I.B. is a recipient of a Fonds FCAR graduate scholarship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aho, S., A. Arffman, T. Pummi, and J. Uiotto. 1997. A novel reporter gene MEL1 for the yeast two-hybrid system. Anal. Biochem. 253:270-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barakat, R. K., M. W. Griffiths, and L. J. Harris. 2000. Isolation and characterization of Carnobacterium, Lactococcus, and Enterococcus spp. from cooked, modified atmosphere, packaged, refrigerated, poultry meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 62:83-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher, I., E. Emond, M. Parrot, and S. Moineau. 2001. DNA sequence analysis of three Lactococcus plasmids encoding phage resistance mechanisms. J. Dairy Sci. 84:1610-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Champagne, C. P., H. Gaudreau, N. Chartier, J. Conway, and E. Fonchy. 1999. Evaluation of yeast extracts as growth media supplements for lactococci and lactobacilli using automated spectrophotometry. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 45:17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champagne, C. P., M. Piette, and D. St. Gelais. 1995. Characteristics of lactococci cultures produced on commercial media. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15:472-479. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chikindas, M. L., K. Venema, A. M. Ledeboer, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1995. Expression of lactococcin A and pediocin PA-1 in heterologous hosts. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 21:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chopin, A., M. C. Chopin, A. Moillo-Batt, and P. Langella. 1984. Two plasmid-determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid 11:260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vos, W. M. 1987. Gene cloning and expression in lactic streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46:281-295. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vos, W. M. 1999. Safe and sustainable systems for food-grade fermentations by genetically modified lactic acid bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 9:3-10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duplessis, M., and S. Moineau. 2001. Identification of a genetic determinant responsible for host specificity in Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 41:325-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrlich, S. D., C. Bruand, S. Sozhamannan, P. Dabert, M.-F. Gros, L. Jannière, and A. Gruss. 1991. Plasmid replication and structural stability in Bacillus subtilis. Res. Microbiol. 142:869-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliker, P. R., A. Anderson, and G. Hannesson. 1956. An agar culture medium for lactic acid streptococci and lactobacilli. J. Dairy Sci. 39:1611-1612. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Émond, E., E. Dion, S. A. Walker, E. R. Vedamuthu, J. K. Kondo, and S. Moineau. 1998. AbiQ, an abortive infection mechanism from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4748-4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Émond, E., B. J. Holler, I. Boucher, P. A. Vandenbergh, E. R. Vedamuthu, J. K. Kondo, and S. Moineau. 1997. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the bacteriophage abortive infection mechanism AbiK from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1274-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Émond, E., R. Lavallée, G. Drolet, S. Moineau, and G. LaPointe. 2001. Molecular characterization of a theta replication plasmid and its use for development of a two-component food-grade cloning system for Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1700-1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frère, J., A. Benachour, M. Novel, and G. Novel. 1993. Identification of the theta-type minimal replicon of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CNRZ270 lactose plasmid pUCL22. Curr. Microbiol. 27:97-102. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gravesen, A., J. Josephsen, A. von Wright, and F. K. Vogensen. 1995. Characterization of the replicon from the lactococcal theta-replicating plasmid pJW563. Plasmid 34:105-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravesen, A., A. von Wright, J. Josephsen, and F. K. Vogensen. 1997. Replication regions of two pairs of incompatible lactococcal theta-replicating plasmids. Plasmid 38:115-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossiord, B., E. E. Vaughan, E. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1998. Genetics of galactose utilization via the Leloir pathway in lactic acid bacteria. Lait 78:77-84. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes, F., P. Vos, G. F. Fitzgerald, W. M. de Vos, and C. Daly. 1991. Molecular organization of the minimal replicon of a novel, narrow-host-range, lactococcal plasmid pCI305. Plasmid 25:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins, D. L., R. B. Sanozky-Dawes, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1988. Restriction and modification activities from Streptococcus lactis ME2 are encoded by a self-transmissible plasmid, pTN20, that forms cointegrates during mobilization of lactose-fermenting ability. J. Bacteriol. 170:3435-3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holo, H., and I. F. Nes. 1989. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:3119-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hueck, C. J., W. Hillen, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1994. Analysis of a cis-active sequence mediating catabolite repression in Gram-positive bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 145:503-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiewiet, R., J. Kok, J. F. M. L. Seegers, G. Venema, and S. Bron. 1993. The mode of replication is a major factor in segregational plasmid instability in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:358-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazo, P. S., A. G. Ochoa, and S. Gascon. 1977. Alpha-galactosidase from Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. Cellular localization and purification of the external enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 77:375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leenhouts, K., A. Bolhuis, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1998. Construction of a food-grade multiple copy integration system for Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49:417-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.London, J. 1990. Uncommon pathways of metabolisn among lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 87:103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucey, M., C. Daly, and G. F. Fitzgerald. 1993. Identification and sequence analysis of the replication region of the phage resistance plasmid pCI528 from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC503. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 110:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maguin, E., P. Duwat, T. Hege, D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1992. New thermosensitive plasmid for gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 174:5633-5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCleary, B. V. 1988. α-Galactosidase from luciferine and guar seed. Methods Enzymol. 160:627-632. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKay, L. L. 1983. Functional properties of plasmids in lactic streptococci. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 49:259-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moineau, S. 1999. Applications of phage resistance in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 76:377-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moineau, S., M. Borkaev, B. J. Holler, S. A. Walker, J. K. Kondo, E. R. Vedamuthu, and P. A. Vandenbergh. 1996. Isolation and characterization of lactococcal bacteriophages from cultured buttermilk plants in the United States. J. Dairy. Sci. 79:2104-2111. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moineau, S., J. Fortier, H. W. Ackermann, and S. Pandian. 1992. Characterization of lactococcal phages from Quebec cheese plants. Can. J. Microbiol. 38:875-882. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moineau, S., S. A. Walker, E. R. Vedamuthu, and P. A. Vandenbergh. 1995. Cloning and sequencing of LlaDCHI restriction/modification genes from Lactococcus lactis and relatedness of this system to the Streptococcus pneumoniae DpnII system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2193-2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naumov, G. I., E. S. Naumova, H. Turakainen, and M. Korhola. 1996. Identification of the alpha-galactosidase MEL genes in some populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a new gene, MEL11. Genet. Res. 67:101-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novick, R. P. 1987. Plasmid incompatibility. Microbiol. Rev. 51:381-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostergaard, S., C. Roca, B. Rønnow, J. Nielsen, and L. Olsson. 2000. Physiological studies in aerobic batch cultivations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains harboring the MEL1 gene. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 68:252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Sullivan, D. J., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1993. High and low-copy-number Lactococcus shuttle cloning vectors with features for clone screening. Gene 137:227-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Platteeuw, C., I. van Alen-Boerrigter, S. van Schalkwijk, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Food-grade cloning and expression system for Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1008-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poolman, B., J. Knol, C. van der Does, P. J. F. Henderson, W.-J. Liang, G. Leblanc, T. Pourcher, and I. Mus-Veteau. 1996. Cation and sugar selectivity determinants in a novel family of transport proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 19:911-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pot, B., L. A. Devriese, D. Ursi, P. Vandamme, F. Haesebrouck, and K. Kersters. 1996. Phenotypic identification and differentiation of Lactococcus strains isolated from animals. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 19:213-222. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rønnow, B., L. Olsson, J. Nielsen, and J. D. Mikkelsen. 1999. Derepression of galactose metabolism in melibiase producing bakers' and distillers' yeast. J. Biotechnol. 72:213-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 47.Schleifer, K. H., J. Kraus, C. Dvorak, R. Kilpper-Balz, M. D. Collins, and W. Fischer. 1985. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci into the genus Lactococcus gen. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 6:183-195. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seegers, J. F. M. L., S. Bron, C. M. Francke, G. Venema, and R. Kiewiet. 1994. The majority of lactococcal plasmids carry a highly related replicon. Microbiology 140:1291-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sårensen, K. I., R. Larsen, A. Kibenich, M. P. Junge, and E. Johansen. 2000. A food-grade cloning system for industrial strains of Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1253-1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson, J., and C. R. Gentry-Weeks. 1994. Métabolisme des sucres par les bactéries lactiques, p. 239-290. In H. De Roissart and F. M Luquest (ed.), Bactéries lactiques. Lorica, Uriage, France.

- 51.Tremblay, D. M., and S. Moineau. 1999. Complete genomic sequence of the lytic bacteriophage DT1 of Streptococcus thermophilus. Virology 255:63-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vincent, S. F., P. J. L. Bell, P. Bissinger, and K. M. H. Nevalainen. 1999. Comparison of melibiose utilizing baker's yeast strains produced by genetic engineering and classical breeding. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Wright, A., S. Wessels, S. Tynkkynen, and M. Saarela. 1990. Isolation of a replication region of a large lactococcal plasmid and use in cloning of a nisin resistance determinant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2029-2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]