Abstract

Objective: To examine the type of information obtainable from scientific papers, using three different methods for the extraction, organization, and preparation of literature reviews.

Design: A set of three review papers was identified, and the ideas represented by the authors of those papers were extracted. The 161 articles referenced in those three reviews were then analyzed using 1) a formalized data extraction approach, which uses a protocol-driven manual process to extract the variables, values, and statistical significance of the stated relationships; and 2) a computerized approach known as “Idea Analysis,” which uses the abstracts of the original articles and processes them through a computer software program that reads the abstracts and organizes the ideas presented by the authors. The results were then compared. The literature focused on the human papillomavirus and its relationship to cervical cancer.

Results: Idea Analysis was able to identify 68.9 percent of the ideas considered by the authors of the three review papers to be of importance in describing the association between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. The formalized data extraction identified 27 percent of the authors' ideas. The combination of the two approaches identified 74.3 percent of the ideas considered important in the relationship between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer, as reported by the authors of the three review articles.

Conclusion: This research demonstrated that both a technically derived and a computer derived collection, categorization, and summarization of original articles and abstracts could provide a reliable, valid, and reproducible source of ideas duplicating, to a major degree, the ideas presented by subject specialists in review articles. As such, these tools may be useful to experts preparing literature reviews by eliminating many of the clerical-mechanical features associated with present-day scientific text processing.

The purpose of this report is to determine the extent to which technical processes and computer applications may enhance the existing approaches in performing scientific literature reviews. The information derived from these processes provides the subject expert with an objective and factual data set of ideas presented by the original authors to evaluate, interpret, and integrate when considering complex medical topics. The topic used for this example involved the relationship between human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer.

The primary form of text analysis currently performed by subject specialists is a manual process. Articles are studied so that ideas, concepts, and data can be identified, extracted, and prioritized. On the basis of these analyses, the specialist constructs a new description—a review—that is used to clarify, summarize, and make scientific judgements about important findings.

As the volume of published literature continues to increase exponentially, the question of computer or technical approaches to replace the manual specialist procedure escalates in importance. This report seeks to describe two approaches—a technical data extraction and a computer-based “idea” extraction from the existing literature.

Using a traditional manual subject specialist approach (referred to in this article as the traditional approach), the expert selects a specific set of articles (based on a particular search strategy) and carefully identifies and extracts information manually. This approach considers the basic investigative reports and selects data from these in construction of the review. The expert must then assess such issues as magnitude of effect, bias, and heterogeneity as well as propose recommendations for future research. In other words, the subject expert ultimately must interpret, evaluate, and make judgements on the information and data presented in the selected articles.

Although these cognitive functions cannot currently be replaced by artificial intelligence programs, certain aspects of the creation of scientific literature reviews can be delegated to computer-based systems and technician-run procedures. Using a defined protocol for the identification and extraction of information from tables and graphs provided in journal articles, technicians extract the data and store them in a relational database for subsequent analysis. This procedure is intended to determine the role of numerically presented information in the final decisions relative to importance of findings from the literature. For the purposes of this paper, this procedure is referred to as formalized data extraction in the text.

A computerized approach involves reading, identifying, extracting, and organizing ideas from the abstracts provided in medline. This approach reduces the effort in constructing knowledge resources. It provides tools for extracting ideas, organizing them, and establishing links with other pertinent data. The process is designed to enhance the cognitive role performed by subject specialists by eliminating the clerical effort. This process is referred to in this article as Idea Analysis.1,10

The objective of this exercise was not to produce a literature review but to determine the degree of agreement in identification of ideas from a specific set of articles selected by subject specialists and used in forming traditional reviews. The identification and extraction procedures that were studied employed a protocol for technician extraction of ideas from data displays (formalized data extraction) and an algorithm for computer extraction of ideas from the abstracts of the selected documents (Idea Analysis). If the technician- or computer-based approaches provided ideas matching those selected and presented by subject specialists, considerable time and energy associated with mechanical-clerical activities could be eliminated, enabling the subject specialist to focus on the true cognitive aspects in the evaluation of information and the creation of knowledge.

Background

The number of articles introduced in the scientific community dramatically changed following World War II. Since then, the number of articles per year has increased exponentially, with a growth rate of approximately 7 percent.2–4 The major innovation in dealing with this informational deluge was the use of computer technology to store bibliographic data concerning each article and the creation and operation of the medline database. However, even in that process, manual coding (i.e., indexing) of information describing the contents of the scientific document was performed. When articles are retrieved, again, manual techniques prevail in extracting information from them, in organizing such information and in arranging the information in new ways.

This emphasis on manual processing impairs the quality of reviews produced by subject specialists in two ways. The first is timeliness of the information. The processing time necessarily forces an arbitrary cutoff in terms of acquiring new information. The additional time spent preparing the review article for publication also affects the timeliness. The result is that the new review, when published, can be up to five years behind current literature.

The second is comprehensiveness. The volume of data representing a topic expands with the number of articles, so a possible review is feasible if the issues it covers are circumscribed. As a result, each review is more focused.

Idea Analysis was developed to offer an alternative to the mechanical, clerical process that requires up to 90 percent of the total effort in forming a new review.5–8 Employing text processing procedures, information in the form of vocabulary and ideas are extracted from the abstracts published in medline. The vocabulary represents information terms—nouns or verbs behaving as nouns (e.g., survival and surviving). The ideas represent couplets of these informational terms that are found in a sentence. The software identifies and stores all such couplets. Operationally, such couplets (e.g., treatment <<>> survival) represent thoughts or ideas presented by the author of the abstract. To avoid problems of interpretation, the authors' vocabulary is used in describing the ideas. No thesaurus is employed.

The approach was tested by building comprehensive descriptions of pediatric cancers.9 A panel of pediatric oncologists reviewed the encyclopedias and judged them to be accurate and complete. Knowledge bases (i.e., organized repositories containing vocabulary, ideas, associated sentences, and bibliographic data) have been constructed dealing with, among others, gynecologic oncology, fertility, environmental toxicants and health effects, and nursing research.10 A recent example of the use of information provided by Idea Analysis in matching expert research strategies has been published.11 A comprehensive description of this approach is available at http://www.xxivcentury.com.12

An early form of Idea Analysis focused on the information presented in the data displays (tables and graphs) provided in the Results sections of articles.13 The inherent datum associated with each numeric display was the fact of an author-specified link between two or more variates. This numeric representation of a relationship was operationally defined to be an idea. Analysis of numerically displayed ideas was found to consist of a necessary and sufficient subset of the total number of ideas presented in articles. With the numeric subset, comprehensive descriptions of subjects could be prepared. These descriptions agreed favorably with a composite of scholarly reviews dealing with the same topic.14,15

The computerized information extraction and organization procedures (Idea Analysis) and technical identification and extraction of numerically displayed relationships (formalized data extraction) provide two objective and impartial ways of obtaining information from complex scientific subjects. The intent of this project was to determine the degree of agreement found in terms of identification of ideas considered by subject specialists in their reviews of a topic with those ideas identified by the two systematic procedures.

Methods

The topic selected as the subject of this investigation was the relationship between the human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. Identification of articles on this topic was performed by using a comprehensive retrieval strategy designed to identify documents reported in medline. The strategy included MeSH subject headings and natural language terms and phrases describing all aspects of gynecologic oncology and related topics. The overly inclusive retrieval strategy was intended to capture “all” the relevant documents, regardless of the number of irrelevant ones also included.16,17 Once the set had been identified, they were processed using the Idea Analysis software to identify those articles that specifically included the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer in at least one sentence of each abstract. Subsequently, each abstract was read to determine which abstracts might be review articles.

A review article was defined as an article that identified itself as such by using the word “review” in the title; an article whose main focus was an overview of the specific association between HPV and cervical cancer, rather than a report of one particular investigation; or a “mini-review” of the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer that was included in a larger, more general subject description. Three review articles (from one selected year) were identified as meeting editorial and reporting criteria for the preparation of scientific literature reviews.18–20 These three reviews cited 161 references, which were retrieved and analyzed using the formalized data extraction and Idea Analysis methods.

The traditional approach of manually extracting information was performed on the review articles only. Each article was read, and a comprehensive list of all the ideas presented by the authors was prepared. For example, the following statement appeared in one of the review articles:

The most common clinical manifestations of HPV infection are skin warts and mucosal condylomata. Other manifestations include respiratory papillomatosis and anogenital warts.18

The ideas extracted were HPV and mucosal condylomata and HPV and anogenital warts. The idea “HPV and skin warts” was not included because the more specific idea “HPV and anogenital warts” is directly related to cervical cancer. Likewise, “HPV and respiratory papillomatosis” is not related to cervical cancer and was not extracted.

The formalized data extraction uses a defined protocol for the identification and extraction of information from tables and graphs that provide numeric displays.21 This process was performed on each of the 161 references cited in the three review papers. Technicians perform this function by extracting the data and storing them in a relational database for subsequent analysis. This procedure is intended to determine the role of numerically presented information in the final decisions relative to importance of findings from the literature. An MS-Access database was created using a specially designed data capture screen known as the Virtual Form System, or VFS.22 The VFS allowed the technician to create a record for each study that described all the variables reported in the data tables, as well as their values and statistical significance, if provided. When the data had been extracted from all the studies, they were imported into an MS-Excel file, in which the information was combined across studies to provide a summary of all the variables investigated.

Idea Analysis is a relatively new concept, and a brief explanation of how this process works is warranted here. As an example, the sentence “Infection by the human papillomavirus (HPV) is considered to be an important risk factor in the development of cervical cancer” can illustrate the identification of ideas. In this instance, the linkages are as follows:

Infection<->HPV,

Infection<->Risk factor,

Infection<->Cervical cancer,

HPV<->Infection,

HPV<->Risk factor,

HPV<->Cervical cancer,

Risk factor<->Infection,

Risk factor<-> HPV,

Risk factor<->Cervical cancer,

Cervical cancer<->Infection,

Cervical cancer<->HPV, and

Cervical cancer<->Risk factor.

The software reads the sentences in the abstract and identifies the ideas composed of couplets of informative terms (nouns or verbs serving as nouns, such as cervical cancer, risk factors, infection, and HPV). For the purpose of this project, the software read all 161 abstracts of the references cited by the review authors.

Displays resembling concept maps can be formed by organizing these couplets into idea sets involving a term or phrase used repeatedly in a number of ideas. Such terms are called primary nodal terms23,24 and form the vocabulary describing the topic. An example of such a term is cervical cancer. The terms or phrases linked by authors in their sentences to cervical cancer define the ideas; that is, each consists of cervical cancer coupled with a second term presented by the authors.

To develop graphic displays of these ideas, the secondary terms can be represented in an outline format. The outline is created manually in a word processing application. This outline is then imported into a graphic software program (known as Inspiration) and is automatically transformed into a concept map. The software allows the user to arrange the concept map diagram. The outline showing terms related to cervical cancer in the sample sentence above is as follows:

Cervical cancer

HPV

Infection

Risk Factor

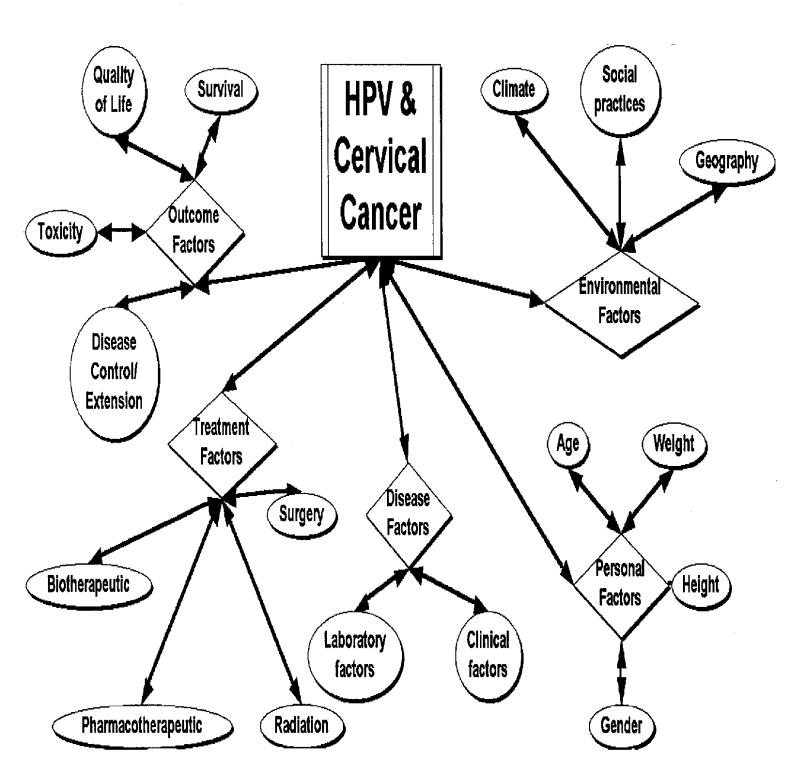

Figure 1▶ shows the general pattern of the concept map. Since the major topic of interest in this investigation was the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer, that couplet is shown using a large rectangle with double-sided lines. To further organize the ideas in a concept map, some filtering and reorganizing can be performed by the user by creating categorical terms that describe clusters of related primary nodes. This restructuring and filtering process also is shown in Figure 1▶. For simplicity, some parts of this first map have been reduced to show only the labels for the categories and subcategories. An example of that simplification is seen in the category Disease Factors. The Clinical Factors and Laboratory Factors categories include ideas involving HPV, cervical cancer, and specific observations or measurements from the clinical and laboratory domains. The major categories related to HPV and cervical cancer are shown by the diamond-shaped symbols. Ellipses were used to further identify elements in a particular grouping. The terms contributing to major categories are:

Figure 1.

A concept map describing topics of interest in the study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer.

Environmental factors, defined as those terms from ideas that describe climate, geographic variation, and social practices

Personal factors, defined as terms from ideas that describe characteristics inherent in the person studied, which include age, weight, height and gender

Disease factors, defined as terms from ideas that describe various attributes representing health or disease. These terms often are subdivided into categories dealing with clinical and laboratory factors

Treatment factors, defined as terms from ideas that describe different therapeutic approaches and include surgery, radiation, and pharmacotherapeutic and biotherapeutic interventions or therapies

Outcome factors, defined as terms from ideas that describe the different end-results from disease or therapeutic interventions, or both, which include survival, disease control (or extension), adverse effects of treatment, and quality-of-life considerations

These major category headings serve merely to organize the ideas.13,25 The arrows connecting terms in the concept maps do not signify importance or causality. They simply indicate which terms belong to each category. The number of ideas expressed by the authors of the scientific documents exceeds the limits of information that can be displayed in a single concept map. Accordingly, the subsequent maps presented here focus only on disease factors and the ideas involved. The environmental, personal, treatment and outcome factors related to HPV and cervical cancer are not reported in this paper.

Results

Traditional Approach

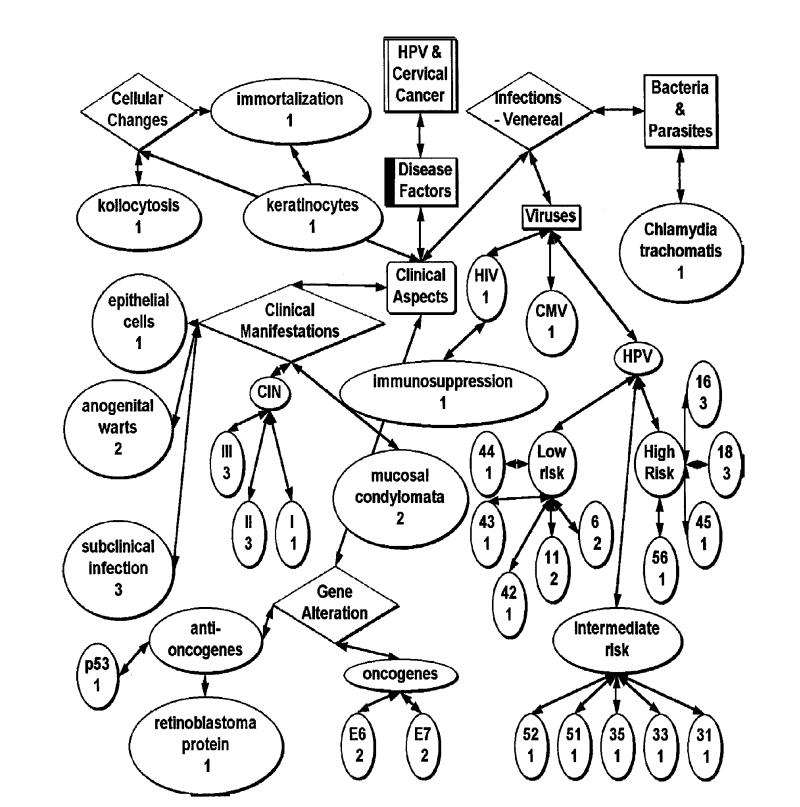

The terms appearing as diamond shapes in Figure 2▶ were assigned by this author. Each of the terms appearing in the ellipses came directly from the authors of the review articles. The placement of the idea groupings on the map is arbitrary and conveys no clinical hierarchy or significance.

Figure 2 .

Clinical aspects of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer reported by the authors of three review articles.

To simulate the traditional approach to literature reviews, the three review articles were read and their ideas were extracted manually. Every attempt was made to include all ideas that were mentioned by the review authors. These ideas included the variables and relationships described by each author. The major sub-category “Clinical Aspects” is expressed by subcategorical terms such as Infections-Venereal, Gene Alterations, Clinical Manifestations and Cellular Changes. The map also describes the number of authors who actually addressed the ideas presented in the figure. (This number is noted in the ellipses, just below the idea term). Reading the concept map clockwise, the venereal infections noted by the authors can be categorized into either bacterial and parasitic infections or viral infections. The singular bacterial and parasitic infection identified was chlamydia trachomatis. The sub-category of viral infections included the author-identified terms cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HPV.

According to the authors, HPV can be classified into three different types: high-, intermediate-, or low-risk, depending on their specific oncogenic potential. The map also provides the exact types of the virus which the authors included in their review papers. By viewing this concept map, one can immediately identify HPV 16, 18, 45 and 56 as high-risk viruses that have been associated with cervical cancer. The high risk types of HPV, notably 16 and 18, were discussed by all three authors. Two other high risk types, 45 and 56, were only mentioned by one of the authors. Likewise, the intermediate risk HPV's (31, 33, 35, 51 and 52) and three of the low risk types (42, 43 and 44) were addressed by only one author. However, HPV 6 and 11, two other low risk types, were discussed by two of the three authors. The changes occurring in the E6 and E7 oncogenes were cited by two authors. However, the genetic alterations which take place in the oncogenes p53 and the retinoblastoma protein were reported by only one author.

Clinical manifestations of infection with HPV included mention of epithelial cells (noted by one author) and anogenital warts (mentioned by two authors). All three authors thought it important to note that most HPV infection is subclinical in nature and is associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). CIN can be identified as either grade I, II or III. Specific cellular changes mentioned by only one author included koilocytosis and immortalization of keratinocytes.

Formalized Data Extraction

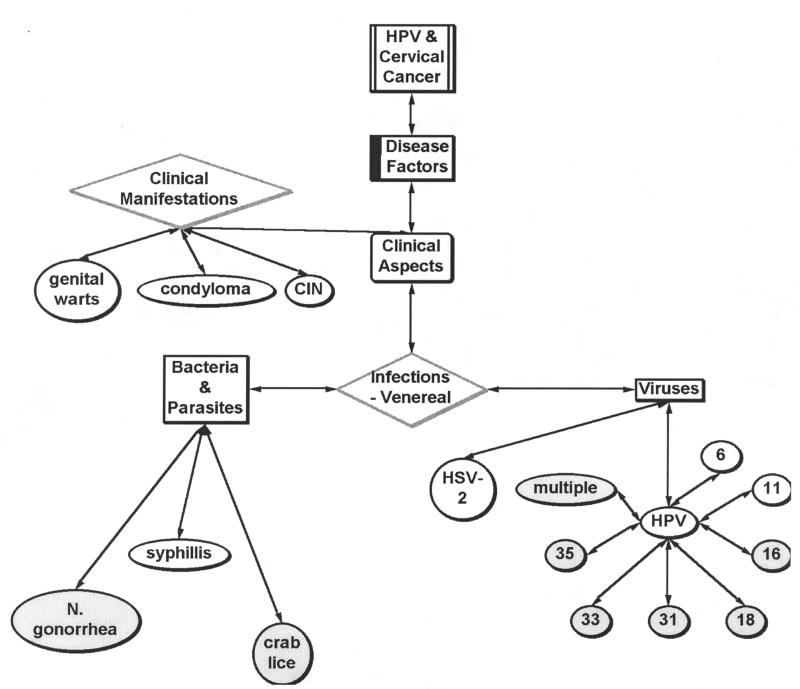

The results of this approach are shown in Figure 3▶. This concept map uses shading to indicate statistical significance, as presented in the data displays of the 161 references cited in the three review articles. If at least one paper reported a statistically significant relationship between a particular variable and cervical cancer, that variable is highlighted by shading on the concept map.

Figure 3 .

Clinical disease factors identified in the formalized data extreaction from the data displays in the original 161 articles cited by the authors of three review papers. Shaded ellipses indicate that at least one investigator reported a statistically signficant relationship between that risk factor and cervical cancer.

In this map, Disease Factors were divided into three categories: viruses, bacteria and parasites and clinical manifestations. HPV infection with either multiple human papillomaviruses or HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, or 35 was significantly related to an increased risk for cervical cancer. No statistically significant association was found with either HPV 6 or 11 or HSV 2. While crab lice and gonorrhea were reported to exhibit a significantly increased risk for cervical cancer, syphilis did not. Clinical manifestations reported in data displays included genital warts, condyloma, and CIN, none of which was identified as having a statistically significant role in cervical cancer.

Far fewer ideas were uncovered in the formalized data extraction than in either of the other two approaches, because this analysis centered only on the information presented in the data displays of the original articles. However, this limited picture does provide some insight into the types of information that the original authors thought important enough to highlight in their papers. It also provides the reader with a quick and easily understood map of the data the original authors reported in their research and their statistical significance, compared with what the review authors considered appropriate to include in their analyses and what they considered significant factors in the development of cervical cancer.

Idea Analysis

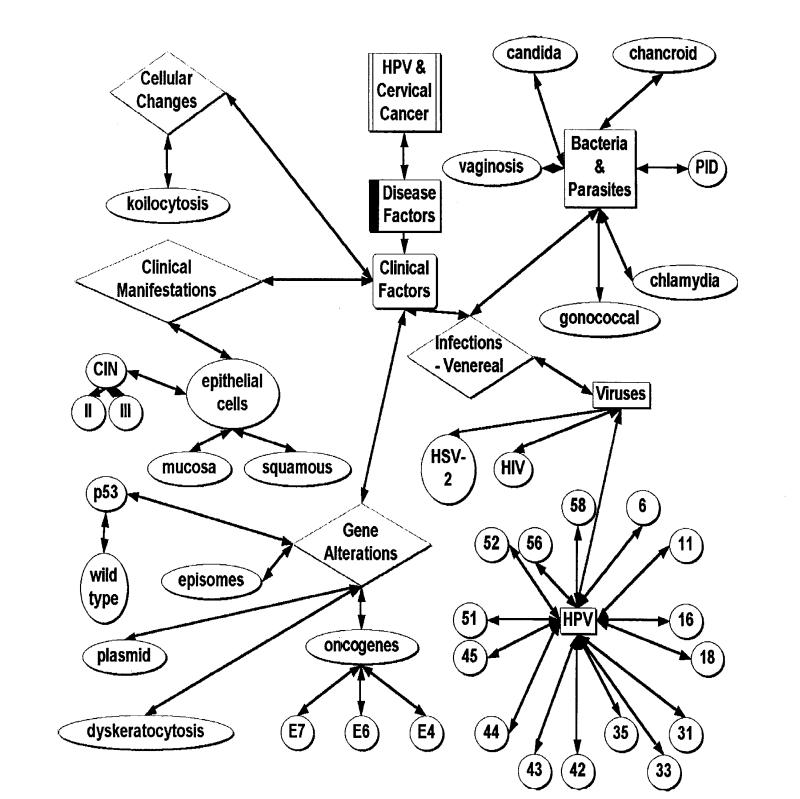

The clinical disease factors shown in Figure 4▶ describe the ideas that were identified in the abstracts of the 161 articles cited as references by the authors of the three reviews. Those elements included venereal infections, gene alterations, clinical manifestations, and cellular changes. Each of these subcategories is further defined by the ideas associated with them in the literature.

Figure 4 .

Disease factors identified in the Idea Analysis from the 161 references cited by the review authors.

In contrast to the concept map based on ideas identified in the traditional approach, the Idea Analysis concept map presents a slightly different but not discordant view of HPV and cervical cancer. Several additional forms of bacterial infection were identified in the Idea Analysis, including chancroid, PID, gonococcal, vaginosis, and candida. With regard to HPV types, 15 variations of the virus have been identified, but it is not apparent which strains increase the risk of cervical cancer. The Idea Analysis reported author-presented connections (of uncertain importance) to the herpes simplex virus (HSV2) and HIV. The additional gene alteration processes involving dyskeratocytosis, plasmids, and episomes, not revealed in the traditional approach or the formalized data extraction, are apparent in the Idea Analysis, along with the inclusion of the E4 oncogene. Clinical manifestations are described in the Idea Analysis by the type of cells involved in the disease (epithelial cells) as well as by the early stages of cervical dysplasia, known as CIN II and CIN III. Only one aspect of cellular changes, namely koilocytosis, was identified in the Idea Analysis.

Discussion

To further evaluate the usefulness and accuracy of the information that can be identified by the traditional approach, the formalized data extraction, and the Idea Analysis, the number of ideas identified by each type of analysis can be determined. Table 1▶ describes the total number of ideas identified by each analytic method using terms related to the disease factors category (all terms identified by ellipses on the concept maps), as well as the number of those ideas unique to each analysis. The traditional approach described 37 ideas related to clinical disease factors of HPV and cervical cancer, 10 of which were not identified in either the Idea Analysis or the formalized data extraction. Thirty-eight ideas were identified by Idea Analysis, 11 of which were not picked up by the traditional method or the formalized data extraction. Also, Idea Analysis identified the largest number of ideas because there was no filtering process to determine which ideas were of greater importance than others.

Table 1.

▪ Number of Ideas from Disease Factors Found Exclusively by Each Source.

| Source | No. of Ideas Identified* | No. of Ideas Not Reported by Other Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional approach | 37 | 10 |

| Idea Analysis | 38 | 11 |

| Formalized data extraction | 15 | 3 |

*Total number of ideas identified. The number of ideas not reported by the other sources is a subject of this total.

Whereas the traditional approach and the Idea Analysis were more inclusive in their recognition of ideas, the formalized data extraction identified only those ideas that were highlighted in data displays by the authors of the original articles cited by the review authors. In addition to the small number of ideas presented (only 15), 20 percent of those ideas were not discussed in the traditional approach or included in the Idea Analysis. Of those 15 ideas, however, eight were reported to have a statistically significant relationship to HPV and cervical cancer.

The reason for the discrepancies in the number of ideas and the type of ideas presented in each of the three approaches relates to the level of cognitive function applied in each instance. The traditional approach relies on expert opinion of the interactions that might be taking place among the various infectious, genetic, cellular, and clinical factors. It is the expert's job to sort out which ideas are important and could affect the progression of the disease. In this instance, the experts speculated on an additional ten variables that were not included in either of the other two analyses—specifically, anti-oncogenes, CIN I, CMV, high risk, immortalization, immunosuppression, intermediate risk, low risk, retinoblastoma protein, and subclinical infection.

On the other hand, the Idea Analysis relies strictly on a computer to identify the links made by the original authors in their articles. There is no way to attach importance to any of the ideas. The computer simply provides the most comprehensive list of possible ideas to be considered by investigators studying the etiology of cervical cancer.

Table 2▶ compares the number of ideas identified in the traditional approach with the number of ideas identified in the formalized data extraction. The bolding indicates agreement between the two methods. Thirty-seven different terms were associated with the traditional approach, which was considered the gold standard. Ten of those terms were found in the formalized data extraction, which equates to a 27 percent agreement rate between the two methods.

Table 2.

▪ Comparison of Ideas Identified by Review Authors and Ideas Identified Through the Formalized Data Extraction

| Traditional Approach | Formalized Data Extraction |

|---|---|

| Anogenital warts | Genital warts |

| Anti-oncogenes | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

| CIN I | CIN |

| CIN II | |

| CIN III | |

| CMV | Crab lice |

| E6 | |

| E7 | |

| Epithelial cells | |

| HIV | |

| High risk | |

| HPV 6 | 6 |

| 11 | 11 |

| 16 | 16 |

| 18 | 18 |

| 31 | 31 |

| 33 | 33 |

| 35 | 35 |

| 42 | Multiple |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 56 | |

| Immortalization | HSV-2 |

| Immunosuppression | |

| Intermediate risk | |

| Keratinocytes | |

| Koilocytosis | |

| Low risk | |

| Mucosal condylomata | Condyloma |

| Oncogenes | N. gonorrhea |

| p53 | |

| Retinoblastoma protein | |

| Subclinical infection | Syphilis |

Note: Bolding indicates agreement between the two approaches.

Table 3▶ compares the number of ideas identified in the traditional approach with the number found in the Idea Analysis. Because the review authors used the descriptor “mucosal condylomata” and the Idea Analysis software picked up only the term “mucosa,” those particular terms were counted as only a partial match. With that in mind, there were 25.5 matching terms in the traditional approach and the Idea Analysis, resulting in a 68.9 percent agreement rate. The combination of the terms identified in the Idea Analysis (25.5 terms) and the formalized data extraction (with two additional new terms, “genital warts” and “condyloma”) recognized 74.3 percent of the ideas considered important by the authors of the three review articles. The result is that 25.7 percent of the ideas expressed by the review authors were unique to them.

Table 3.

▪ Comparison of Ideas Identified by Review Authors and Ideas Identified Through the Idea Analysis

| Traditional Approach | Idea Analysis |

|---|---|

| Anogenital warts | Candida |

| Anti-oncogenes | Chancroid |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Chlamydia |

| CIN I | Gonococcal |

| CIN II | CIN II |

| CIN III | CIN III |

| CMV | E4 |

| E6 | E6 |

| E7 | E7 |

| Epithelial cells | Epithelial cells |

| HIV | HIV |

| High risk | Episomes |

| HPV 6 | 6 |

| 11 | 11 |

| 16 | 16 |

| 18 | 18 |

| 31 | 31 |

| 33 | 33 |

| 35 | 35 |

| 42 | 42 |

| 43 | 43 |

| 44 | 44 |

| 45 | 45 |

| 51 | 51 |

| 52 | 52 |

| 56 | 56 |

| Immortalization | 58 |

| Immunosuppression | HSV-2 |

| Intermediate risk | PID |

| Keratinocytes | Dyskeratocytosis* |

| Koilocytosis | Koilocytosis |

| Low risk | Wild type |

| Mucosal condylomata | Mucosa |

| Oncogenes | Oncogenes |

| p53 | p53 |

| Retinoblastoma protein | Plasmid |

| Subclinical infection | Vaginosis |

| Squamous |

Note: Bolding indicates agreement between the two approaches.

* “Keratinocytes” refers to the cells of the epidermis that synthesize keratin. “Dyskeratocytosis” refers to the abnormal synthesis of keratin by the keratinocytes.

It is likely that the filtering process that the experts apply as they write reviews accounts for some of this discrepancy. Some of this filtering took the form of categorization, as in the description of strains of HPV as either low-, intermediate-, or high-risk types and the labeling of “anti-oncogenes.” The other ideas unique to this approach would come from the knowledge base of each of the three review authors.

The formalized data extraction was defined in such a manner that it provided a smaller number of ideas than either the traditional approach or the Idea Analysis methods. This was not done intentionally. However, the formalized data extraction records only those variables that the original authors consider statistically significant or important enough to be included in data displays in the article. Both the traditional approach and the Idea Analysis provided a more robust set of descriptors, but the importance of the variables is not provided in a reproducible, objective fashion. Each of these analyses relies ultimately on the interpretation of the subject specialist in deciding importance. In this sense, the separation of procedures (i.e., technical vs. cognitive) results in separate approaches to the evaluation. The technical approach involving technicians or computer software can provide assurances of accuracy, reproducibility, and completeness. The cognitive approach involves the expertise and experience of the individual in developing the evaluation, judgment, interpretations, and extrapolations necessary in expanding knowledge of a subject.

As stated at the beginning of this article, the objective of this research was not to produce a literature review but to examine the type of information that could be obtained on a particular topic using a formalized data extraction and a computerized approach. The three review articles that were used as the source for a test set of papers were selected because they provided the best overall description of HPV and cervical cancer that could be found in single articles published in a single year (1995). Such a test set is adequate for comparison of the three technical approaches. If our objective had been to find the best literature reviews, we would have looked at all years. If our objective had been to use the three approaches to generate a literature review, we would have included all original studies on the topic and all aspects of the subject from environmental factors to outcomes.

The formalized approach and Idea Analysis are designed to let the novice investigator learn more about a new subject in a relatively short time. Idea Analysis looks at all published articles on this subject without filtering them by such factors as study design, geographic region, or principal investigators. The formalized data extraction looks at all articles that provide data tables, regardless of these factors. Although the novice investigator may not be able to make the appropriate evaluation and interpretations of the literature that are expected of an expert, they would have a thorough grasp of the issues involved in the development of the disease and an understanding of the factors that have already been studied by investigators.

This highlights the difference between the notion of extracting scientific knowledge and the notion of extracting research ideas. Knowledge is an organized body of information arrived at by consensus over a period of time.26–28 Although this information is generally accepted by authorities in the particular subject, it remains subject to change, and portions of it can be removed, modified, or replaced. Ideas, on the other hand, may or may not be part of this organized body of information. They are the ever-evolving elements that provide the fodder for knowledge to grow and expand. They are the questions that investigators must answer. Based on those answers, ideas either become incorporated into a knowledge base, removed entirely from consideration, or modified and replaced with new ideas.

Conclusions

The manual extraction of information imposes a considerable clerical burden on an investigator. Computerized approaches that eliminate the clerical functions are needed to relieve experts from this burden and allow them to concentrate on the cognitive functions of interpreting, evaluating, and judging the evidence and making new connections that lead to progress.

Idea Analysis provides that capability by identifying and organizing the ideas from the literature for consideration by the individual. The formalized data extraction affords a level of analysis based on the data presented in original articles, presumably the most important findings the authors uncovered. The results obtained by use of a combination of both methods, when presented to the subject expert, should allow the expert free rein to exercise cognitive functions without the drain of the clerical ones. In that sense, the processing of scientific ideas represented in the published literature could be improved using these technical procedures to enhance the preparation of literature reviews and contribute to the overall productivity and progress of science.

References

- 1.Weiner JM, Schuster JHR, Horowitz RS. Development of Research Strategies and Designs. Buffalo, NY: 24th Century Press, 1994.

- 2.Archibald G, Line MB. The size and growth of serial literature 1950–1987, in terms of number of articles per serial. Scientometrics. 1991;20(1):173–96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durack DT. The weight of medical literature. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(14):773–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner JM, Shirley S, Gilman NJ, Stowe SM, Wolf RM. Access to data and the information explosion: oral contraceptives and risk of cancer. Contraception. 1981;24:301–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner JM, Horowitz RS. Idea analysis: a combination of knowledge representation and rule-based information processing in creating research strategies. In: Feeney M, Merry K (eds): Information Technology and the Research Process. London, UK: Bowker-Saur, 1990:52–71.

- 6.Malogolowkin MH, Horowitz RS, Ortega JA, Siegel SE, Hammond GD, Weiner JM. Tracing expert Thinking in clinical trial design. Comput Biomed Res. 1989:22:190–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malogolowkin MH, Ortega JA, Siegel SE, Horowitz,RS, Hammond GD, Weiner JM. Idea analysis: a new approach in using scientific literature. Int J Man–Machine Studies. 1989;31:573–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J. The natural structure of scientific knowledge: an attempt to map a knowledge structure. J Inf Sci. 1988;14:131–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner JM, Malogolowkin MH, Horowitz RS (eds). Encyclopedia of Ideas in ALL, ANLL, Brain Tumors, Germ Cell Cancers, HD, Pediatric Tumors, NHL, Sarcomas. Idea Analysis in Cancer Series. Burbank, Calif: Literature Analysis Inc., LAI. 1990–1993.

- 10.Weiner JM, Horowitz RS, Schuster JHR (eds). Knowledge Bases in Medicine. Wilmington, Del: 24th Century Press, 2000. Also available at: http:http:www.xxivcentury.com; accessed 1/11/01.

- 11.Tworek C, Weiner JM. Gene–Environment Interactions in Head and Neck Cancer: A Case Study using Idea Analysis. Wilmington, Del: 24th Century Press, 2000. Available at http://63.236.75.181 > documents > class > spm612 > 990320.zip > download; accessed 1/11/01.

- 12.Weiner JM. Research Strategies and Design [class notes]. Available at http://63.236.75.181 documents > class > spm612 > 000207.zip > download; accessed 1/11/01.

- 13.Weiner JM. Text analysis and basic concept structures. Inf Proc Manage. 1983;19(5):313–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller SS, Gilman NJ, Weiner RE, Stanley D, Weiner JM. The literature of decision making: an analytical approach. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci. l982;19:100–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi N, Latinwo L, Horowitz RS, Weiner JM. Quantitatively expressed ideas in lymphoma: text versus numerical displays. Med Inform. 1987;12:273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purcell GP, Mar DD. SCOUT: information retrieval from full-text medical literature. Proc 16th Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1992:91–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.McKinin EJ, Sievert M, Johnson Ed, Mitchell JA. The medline/full-text research project. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1991;42(4): 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adimora AA, Quinlivan EB. Human papillomavirus infection: recent findings on progression to cervical cancer. Postgrad Med. 1995;98(3):109–12,115–6,120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birley HD. Human papillomaviruses, cervical cancer and the developing world. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;89: 453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson K. Periodic health examination, 1995 update, part 1: Screening for human papillomavirus infection in asymptomatic women. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:483–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piniewski-Bond JF. Determining the types of information obtainable from three methods of preparing scientific literature reviews [master's thesis]. Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo, 1997.

- 22.Schuster JHR. Virtual Form System. Phoenix Workgroup. 1995.

- 23.Malogolowkin MH, Horowitz RS, Ortega JA, Siegel SE, Hammond GD, Weiner JM. Tracing expert thinking in clinical trail design. Comput Biomed Res. 1989;22(2):190–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner JM, Horowitz RS. Idea analysis: a combination of knowledge representation and rule-based information processing in creative research strategies. In: Feeney M, Merry K (eds). Information Technology and the Research Process: Proceeding of a Conference held at Cranfield Institute of Technology, Jul 18–21, 1989. London: Bowker-Saur. 1990:52–71.

- 25.Weiner JM, Stowe SM, Fuller SS,Gilman NJ. The size of the document set and conceptual structure identification. Proc Am Soc Inf Sci. 1982;19:327–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Findlay CS, Lumsden CJ. The Creative Mind. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press, 1988.

- 27.Davies R. The creation of new knowledge by information retrieval and classification. J Documentation. 1989;45: 273–301. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies R. Generating new knowledge by retrieving information. J Documentation. 1990;46:368–72. [Google Scholar]