Abstract

The C2 domain of protein kinase Cα (PKCα) controls the translocation of this kinase from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane during cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals. The present study uses intracellular coimaging of fluorescent fusion proteins and an in vitro FRET membrane-binding assay to further investigate the nature of this translocation. We find that Ca2+-activated PKCα and its isolated C2 domain localize exclusively to the plasma membrane in vivo and that a plasma membrane lipid, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), dramatically enhances the Ca2+-triggered binding of the C2 domain to membranes in vitro. Similarly, a hybrid construct substituting the PKCα Ca2+-binding loops (CBLs) and PIP2 binding site (β-strands 3–4) into a different C2 domain exhibits native Ca2+-triggered targeting to plasma membrane and recognizes PIP2. Conversely, a hybrid containing the CBLs but lacking the PIP2 site translocates primarily to trans-Golgi network (TGN) and fails to recognize PIP2. Similarly, PKCα C2 domains possessing mutations in the PIP2 site target primarily to TGN and fail to recognize PIP2. Overall, these findings demonstrate that the CBLs are essential for Ca2+-triggered membrane binding but are not sufficient for specific plasma membrane targeting. Instead, targeting specificity is provided by basic residues on β-strands 3–4, which bind to plasma membrane PIP2.

INTRODUCTION

Recruitment of signaling proteins to specific membranes using modular targeting domains is a central theme in signal transduction (Rizo and Sudhof, 1998; Hurley and Misra, 2000; Teruel and Meyer, 2000; Itoh and Takenawa, 2002; Lemmon, 2003). Many targeting domains, such as pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, specifically recognize phospholipid components of their target membranes, thus conferring intracellular targeting specificity to the host protein. Another widely distributed targeting domain, the C2 domain, responds to intracellular calcium signals and mediates the transient and reversible translocation of its host protein to intracellular membranes (Coussens et al., 1986; Rizo and Sudhof, 1998). Recent evidence suggests that specific interactions between membrane phospholipids and C2 domains may also account for the ability of some C2 domains to translocate specifically to a single type of intracellular membrane (Bai et al., 2004).

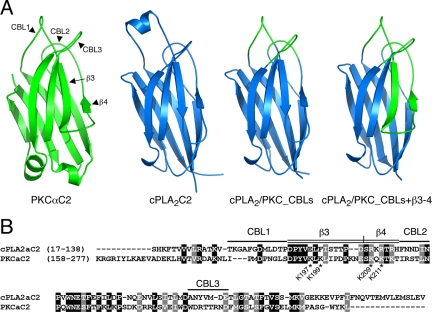

Protein kinase Cα (PKCα) is a member of the conventional PKC subgroup of serine/threonine protein kinases (cPKC; α, βI, βII, and γ isoforms), which, with the atypical (aPKC) and new (nPKC) subgroups, comprise the PKC family (Nishizuka, 1995). The PKCα C2 domain is structurally characterized by eight antiparallel β strands connected by interstrand loops to form a beta-sandwich structure (see Figure 1A; Verdaguer et al., 1999). After increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, the PKCα C2 domain binds 2 Ca2+ ions in a pocket defined by three interstrand loops (Ca2+-binding loops or CBLs), leading to a favorable electrostatic interaction with the isolated headgroup of the anionic lipid phosphatidylserine (PS) (Verdaguer et al., 1999) and with PS-containing membranes (Murray and Honig, 2002; Evans et al., 2004). Previous studies have concluded that the CBLs are primarily or fully responsible for specific targeting to the plasma membrane in preference to other intracellular membranes (Stahelin et al., 2003; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005). In addition to the CBLs, a second membrane-interacting region consisting of basic residues in the β-hairpin formed by β strands 3 and 4 has been identified and shown to interact with PS or another membrane lipid, PIP2 (Verdaguer et al., 1999; Ochoa et al., 2002; Corbalan-Garcia et al., 2003). Mutations at key positions in the CBLs or in the β3–4 hairpin interfere with plasma membrane interaction in vivo and reduce the affinity of the PKCα C2 domain for PS or PIP2 in vitro (Medkova and Cho, 1998; Ochoa et al., 2002; Bolsover et al., 2003; Stahelin et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Alfaro et al., 2004; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Structure and sequence of wild-type PKCα and cPLA2α C2 domains and of hybrid C2 domains. (A) Ribbon diagrams of the PKCα C2 domain, showing CBLs 1–3 and β strands 3–4 (green, PDB entry 1DSY) of the cPLA2α C2 domain (blue, PDB entry 1RLW), of the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs C2 domain (PKCαC2 CBLs in green, cPLA C2 scaffold in blue), and of the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 C2 domain (PKCαC2 CBLs and β3–4 strands in green, cPLA2C2 scaffold in blue). (B) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the PKCα C2 and cPLA2α C2 domains used to generate the hybrid domains. Conserved residues in black boxes, and similar residues in gray. CBL residues included in hybrids are identified by a single line. Residues of β strands 3 and 4 included in hybrids are identified by a double line. Mutated lysine residues in β strands 3 and 4 of PKCα C2 are indicated by asterisks.

A significant and unresolved question concerns how the two membrane-interacting regions in the C2 domain together direct specific translocation of PKCα to the plasma membrane. In particular, the relative contributions of these two regions to the driving forces underlying 1) general, nonspecific docking to anionic membranes and 2) specific docking to the plasma membrane remain unknown. Using time-lapse epifluorescence microscopy of fluorescent proteins in vivo and protein-to-membrane FRET studies of membrane docking in vitro, we have investigated the roles of the CBLs and the β3–4 hairpin in targeting the PKCα C2 domain from the cytoplasm to intracellular membranes, as well as their contributions to specific plasma membrane docking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Ionomycin was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). DiD and FM4-64 were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Fusion Protein Constructs

Construction of the plasmids encoding the human PKCα and PKCα C2 domain (a gift from J.-W. Soh, Inha University, Incheon, Korea) fused to cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) (pCFP-PKCα and pCFP-PKCαC2) were previously described (Evans et al., 2004). Mutant plasmids (pCFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A and pCFP-PKCα/K209A/K211A) were produced by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Plasmids encoding the human cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) C2 domain (accession M72393) containing CBLs 1, 2, and 3 from PKCαC2 (pCFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs) or both the PKCα C2 CBLs and β3–4 strands (pCFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4) were assembled from overlapping PCR fragments obtained by amplification of pCFP-cPLA2C2 with cPLA2C2fwd and cPLA2C2rev primers and primers containing the PKCαC2 CBL sequences and β3–4 strand sequences. The fragments were assembled by PCR and cloned into the HindIII/SalI site of ECFP(C3). The resulting amino acid sequence of the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs hybrid contained cPLA2C2 sequences (S17-V30, D43-H62, P69-D93, T101-M148) interrupted by insertion of PKCαC2 loop sequences (I184-S192, I215-N220, W247-D254). The resulting amino acid sequence of the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 hybrid contained cPLA2C2 sequences (S17-V30, P69-D93, T101-M148) interrupted by insertion of PKCαC2 loop and β3–4 strand sequences (I184-N220, W247-D254). Because of differing topologies, the PKCαC2 β3–4 strands are homologous to the cPLA2C2 β2–3 strands.

Plasmids containing the N-terminal 20 residues of GAP43 fused to CFP or YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) (mGAP43-CFP and -YFP, respectively) were purchased from BD Biosciences Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). TGN38-CFP and TGN38-YFP plasmids were gifts from K. Simons (Max Planck Institute, Dresden, Germany). EGFP-PLCδ1PH domain plasmid was a gift from M. Katan (Cancer Research UK Centre for Cell and Molecular Biology, London, United Kingdom).

The pYFP plasmid used in this study was constructed from pEYFP purchased from BD Biosciences Clontech by introducing a Q70M mutation by site directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) to improve its qualities (Griesbeck et al., 2001). Interchanging the NheI/BsrGI fragments encoding the fluorescent protein produced different color fluorescent protein plasmids.

For in vitro lipid-binding studies, PKCαC2, cPLA2/PKC_CBLs, and cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 sequences were amplified using primers PKCαC2-GSTfwd and PKCαC2-GSTrev, for PKCαC2, and cPLA2C2-GSTfwd and cPLA2C2-GSTfwd, for the hybrids, and cloned into the EagI/EcoRI site of a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion vector. Proteins expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL12D were isolated on a glutathione affinity column before cleavage with thrombin and elution. Protein purity was determined by SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970), and protein concentration was determined by the tyrosinate difference spectral method (Copeland, 1994). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were plated on 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 and cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.292 mg/ml glutamine in 5% CO2 at 37°C. On the second day, cells were transfected with 1–2.5 μg each of the relevant plasmids using FuGENE-6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in DMEM containing 0.2% BSA, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.292 mg/ml glutamine following the manufacturer's protocol.

Microscopy of Fluorescent Proteins

Cotransfected MDCK cells were washed with and incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution additionally buffered with 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 (HH-BSS). Cells were imaged using an Olympus inverted microscope (Melville, NY) equipped with a 60×, 1.25 NA oil immersion objective, CFP and YFP emission filters (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT) in a Sutter filter wheel, a CFP/YFP dichroic mirror, and a TILL Imago CCD camera (TILL Photonics, Grafelfing, Germany). Excitation light of 430 and 510 nm for CFP and YFP, respectively, was provided using a Polychrome IV monochromator (TILL Photonics). Images in Figures 3 and 4 were acquired using a Nikon inverted microscope (Melville, NY) equipped with a 60× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective, CFP/YFP/RFP dichroic mirror and corresponding single band excitation and emission filers (Chroma Technology), and a CoolSNAP ES camera (Photometrics, Tucson AZ). Excitation light was provided by a mercury lamp. In all experiments, cells were stimulated with 10 μM ionomycin between acquisition of the first and second CFP/YFP image sets. Intervals between image sets were 5–10 s. TILLvisION software was used for image acquisition and analysis. Final images were produced using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA) and ImageJ (NIH, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Surface plots and videos were produced with ImageJ.

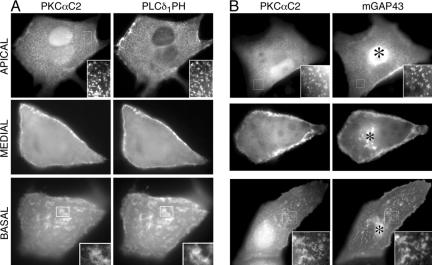

Figure 3.

The PKCα C2 domain colocalizes with the PLCδ1 PH domain and mGAP43 at different focal planes after translocation. Images of cells coexpressing (A) YFP-PKCαC2 (left) and CFP-PLCδ1PH (right) after treatment with ionomycin at apical (top), medial (middle), and basal (bottom) planes of each cell. The same cell is imaged at a given focal plane. Insets, enlarged views of the indicated cell regions. The intracellular distribution of CFP-PLCδ1PH did not change significantly before or after ionomycin treatment. (B) Images of three cells coexpressing YFP-PKCαC2 (left) and mGAP43-CFP (right) after treatment with ionomycin at apical (top), medial (middle), and basal (bottom) planes of each cell. Insets, enlarged views of the indicated cell regions. The same cell is imaged at a given focal plane. Perinuclear targeting of mGAP43-CFP to Golgi is designated by an asterisk (right images). All results are representative of a minimum of five experiments.

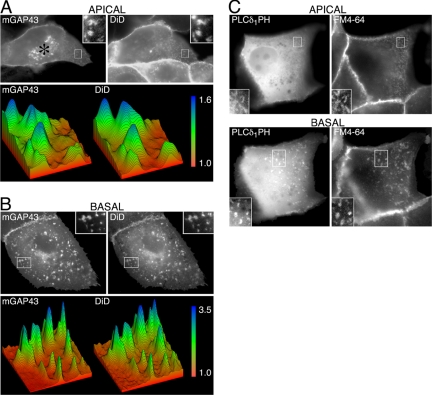

Figure 4.

Colocalization of mGAP43 and PLCδ1 PH domain with DiD. (A) Apical surface of a cell expressing mGAP43-YFP (left) stained with the lipophilic membrane dye DiD (right). Cells were incubated with 25 μM DiD for 5 min at 37°C, rinsed with ice-cold HHBSS, and kept on ice until imaged to prevent the dye from staining internal membranes. Focus is on the apical surface. Insets, white-boxed areas. Surface plots (bottom) of the areas in the mGAP43 (left) and DiD (right) insets. Scale bar reflects fold increases in fluorescence intensities with the intensity of the dim surrounding membrane set to 1. (B) Basal surface of a cell expressing mGAP-YFP (left) and stained with DiD (right). Surface plots (bottom) of the areas in the mGAP43 (left) and DiD (right) insets. Scale bar reflects fold increases in fluorescence intensities. (C) Apical (top) and basal (bottom) surfaces of a cell expressing CFP-PLCδ1PH (left) stained with the lipophilic membrane dye FM4-64 (right). Cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml FM4-64 for 5 min in ice-cold HHBSS, rinsed, and kept on ice until imaged to prevent the dye from staining internal membranes.

Lipid-binding Studies

The lipids used were 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (phosphatidylcholine, PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (phosphatidylserine, PS), and L-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5,-bisphosphate (PIP2) from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The fluor used was N-[5-dimethylamino-naphthalene-1-sulfonyl]-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (dansyl-PE, dPE) from Molecular Probes. Lipids were dissolved in chloroform/methanol/water (1/2/0.8) to give a ratio of 71.25: 23.75:5 PC:PS:dPE or 66.75:22.25:6:5 PC:PS:PIP2:dPE, dried under vacuum at 45°C until all solvents were removed, and then hydrated with buffer A (25 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4, with KOH, 140 mM KCl and 15 mM NaCl, and 1 mM MgCl2) by rapid vortexing. Sonicated small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared by sonication of the hydrated lipids to clarity with a Misonix XL2020 probe sonicator (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY). After sonication, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation.

To measure proteins binding to lipids, equilibrium fluorescence experiments were carried out on a Photon Technology International QM-2000–6SE fluorescence spectrometer (Lawrenceville, NJ) at 25°C in buffer A essentially as described (Nalefski et al., 1997). The excitation and emission slit widths were 2 and 8 nm, respectively, for all equilibrium fluorescence experiments. FRET was measured between donor intrinsic tryptophans in the proteins and SUVs composed of PC/PS/dPE or PC:PS:PIP2:dPE containing the acceptor, dansyl-PE. CaCl2 was titrated in mixtures of wild-type or hybrid C2 domains (1 μM) and SUVs (100 μM total lipid concentration) in buffer A, and the protein-to-membrane FRET was monitored by the increase in dPE emission using excitation and emission wavelengths of λex = 284 nm and λem = 520 nm, respectively. The fluorescence due to the direct excitation of the dPE was subtracted from the protein data. Averages ± SD for three experiments are presented in the graph. Curves represent best-fit of data by the Hill equation using KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

Structural Models

The Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000) identifiers for the experimentally determined C2 domain models in Figure 1 are 1RLW (cPLA2αC2; Perisic et al., 1998), and 1DSY (PKCαC2; Verdaguer et al., 1999). The hybrid C2 domain models illustrated in Figure 1A were constructed by placing the respective CBL and β3–4 regions from PKCαC2 onto the structural core of cPLA2C2. The structure of cPLA2C2 was superimposed onto the PKCαC2 structure using the program CE (Combinatorial Extension; Shindyalov and Bourne, 1998). Once structurally aligned, the appropriate portions of the PKCαC2 PDB file replaced regions of the cPLA2αC2 PDB file as dictated by the sequences given in Figure 1B. The hybrid C2 domain models were energy minimized in the program Modeller (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) (Sali and Blundell, 1993) to fix any mismatches between the various structural segments. Because the calcium coordination schemes of the hybrid C2 models are closest to that of PKCαC2 as judged by the multiple sequence alignment of the various constructs, it was assumed that the hybrid C2 models bind two calcium ions in the same manner as PKCαC2.

RESULTS

Intracellular Targeting of Native PKCα and Its C2 Domain

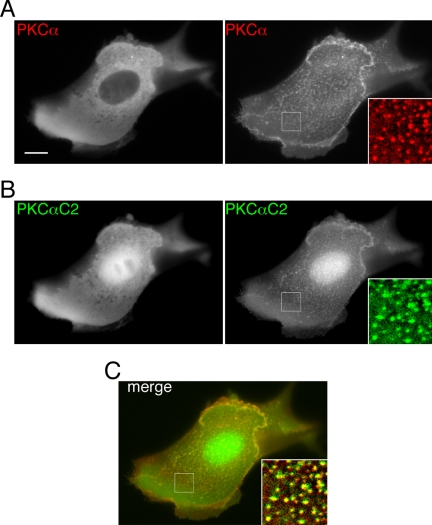

To monitor the intracellular targeting of PKCα in response to Ca2+ mobilization, we fused PKCα to CFP, expressed the fusion protein in MDCK cells, and imaged its cellular localization during increases in the cytoplasmic Ca2 concentration produced by treatment of cells with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin. In unstimulated cells, both CFP-PKCα and the isolated C2 domain from PKCα fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP-PKCαC2) were diffusely distributed in the cytosol (Figure 2, A and B). Because of its small molecular mass, YFP-PKCαC2 was also observed in the nucleus, as are many small domains fused to fluorescent proteins (Balla and Varnai, 2002). In response to an increase in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, CFP-PKCα translocated from the cytosol to the cell periphery and to small puncta on the apical surface of the plasma membrane, where it colocalized with YFP-PKCαC2, (Figure 2, A and B, and Supplementary Figure 2video). Because the fluorescence signals from CFP-PKCα and YFP-PKCαC2 colocalized completely (Figure 2C), it follows that the C2 domain not only provides Ca2+ regulation to PKCα, but all requisite targeting information as well.

Figure 2.

PKCα and the isolated PKCα C2 domain target identical puncta in the plasma membrane of MDCK cells. CFP and YFP image pairs of MDCK cells coexpressing (A) CFP-PKCα and (B) YFP-PKCαC2 before (left panels) and 140 s after (right panels) stimulation of a cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal by treatment of cells with 10 μM ionomycin. Focus is on the apical surface of the cell. Insets, enlargements of white-boxed areas and are shown merged in C. Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are representative of multiple cells observed in each of five or more independent experiments.

To investigate the nature of the puncta, we first tested the hypothesis that they lie on the plasma membrane using two different plasma membrane markers, the phospholipase Cδ1 PH domain fused to YFP (YFP-PLCδ1PH), which is widely used as a marker for PIP2 enriched in the plasma membrane (Stauffer et al., 1998; Varnai and Balla, 1998), and the 20-residue doubly palmitoylated targeting region of growth associated protein 43 (GAP43) fused to YFP (mGAP43-YFP), which is known to specifically target plasma and Golgi membranes (Arni et al., 1998). Cells coexpressing CFP-PKCαC2 and YFP-PLCδ1PH were treated with ionomycin to induce Ca2+ mobilization, and the fluorescence from each construct was imaged at apical surface of the cell. For completeness, images were also collected for the basal and medial planes of the cell. The fluorescence signals of CFP-PKCαC2 and YFP-PLCδ1PH overlapped completely (Figure 3A). CFP-PKCαC2 and YFP-PLCδ1 PH fluorescence appeared in bright puncta at the apical surface and in bright patches at the basal surface of the cell. Images of medial sections showed fluorescence at the cell periphery, similar to those images reported by confocal microscopy (Sakai et al., 1997; Oancea and Meyer, 1998; Stauffer et al., 1998). In cells expressing CFP-PKCαC2 and mGAP43-YFP and treated with ionomycin, overlap of the fluorescent signals was identical, except where mGAP43-YFP associates with Golgi, and bright apical puncta and basal patches were again observed (Figure 3B). As expected, the plasma membrane fluorescence of YFP-PLCδ1PH and mGAP43-YFP overlapped in unstimulated cells (Supplementary Figure S1).

In principle, the observed puncta and patches could represent large clusters of lipids and proteins containing high local densities of PIP2 on the cytoplasmic surface of the plasma membrane, such as clusters of lipid rafts (Laux et al., 2000; Raucher et al., 2000; Tall et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2001; Kwik et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2004; Golub and Caroni, 2005). Alternatively, the puncta and patches could represent geometric features arising from high local densities of membrane surface area (Colarusso and Spring, 2002; van Rheenen and Jalink, 2002). To resolve these possibilities, we first used the lipophilic membrane dyes DiD and FM4-64 to provide uniform membrane staining in cells expressing mGAP43-YFP (Raucher et al., 2000; van Rheenen and Jalink, 2002; Golub and Caroni, 2005). Cells expressing low levels of mGAP43-YFP were treated with DiD at 37°C for 5 min before being cooled to 4°C to slow the movement of dye to interior cell membranes. Cells expressing low levels of mGAP43-YFP were selected for analysis because cells expressing high levels of mGAP43-YFP had a considerable fraction of the fluorescence in the cytosol. As seen in Figure 4A, the punctate pattern of mGAP43-YFP at the apical surface overlapped with the DiD staining (top panels). Surface plots of the insets areas were pseudocolored to show fold changes in mGAP43-YFP and DiD intensity over the background membrane (Figure 4A, bottom panel). Both the mGAP43-YFP and DiD puncta were found to be ∼1.6-fold brighter than the surrounding apical membrane, and the areas of brightness overlapped completely (Figure 4A, bottom panel). The brightness and distribution of the DiD-stained apical puncta were similar to those described in a similar study in MDCK cells (Colarusso and Spring, 2002). Analysis of the basal surface of cells expressing mGAP43-YFP and stained with DiD yielded similar results, except that the basal mGAP43-YFP and DiD patches were both found to be three- to fourfold brighter than the surrounding membrane (Figure 4B). Similar experiments using FM4-64 on mGAP43-YFP-expressing cells yielded similar results (unpublished data). These results indicate that the bright apical puncta and basal patches arise from local folding of the plasma membrane rather than regions of lipid and protein heterogeneity (lipid rafts).

To further investigate whether the bright puncta and patches represent high local densities of plasma membrane or PIP2-containing lipid rafts, we imaged the PIP2-specific CFP-PLCδ1PH domain together with the plasma membrane marker FM4-64. CFP-PLCδ1 PH-expressing cells were treated with FM4-64 for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting bright apical puncta and basal patches of CFP-PLCδ1PH were observed to colocalize with FM4-64 (Figure 4C, top panels). Because of the large fraction of CFP-PLCδ1PH in the cytosol not associated with membrane, analysis of brightness differences between FM4-64 and CFP-PLCδ1PH puncta and patches were precluded; however, the fold increase in fluorescence of CFP-PLCδ1PH was consistently lower than that for FM4-64. Again, these results indicate that the observed local accumulations of mGAP43 and PLCδ1PH domain were caused by local increases in membrane density.

Together, our comparisons of the cellular localizations of lipophilic probes and protein domains indicate that mGAP43, PLCδ1 PH, and PKCα C2 are uniformly distributed throughout the plasma membrane within the limit of our optical resolution (∼250 nm). The bright puncta and patches observed on the apical and basal cell surfaces, respectively, represent local regions of high plasma membrane density arising from complex geometric features rather than heterogeneities within the plane of the membrane such as lipid rafts. These findings do not rule out the possibility that heterogeneities or rafts smaller than the limit of our resolution may exist and recruit proteins such as GAP43, PLCδ1, and PKCα.

Overall, the present cellular localization results confirm that Ca2+ activation causes the translocation of full-length PKCα and its isolated C2 domain from the cytoplasm exclusively to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane in preference to other intracellular membranes, as reported in previous studies (Sakai et al., 1997; Oancea and Meyer, 1998; Stauffer et al., 1998). To understand how exclusive plasma membrane targeting is achieved, we next investigated the phospholipid preference of the isolated PKCαC2 protein in an in vitro system.

In Vitro Association of Native PKCα C2 Domain with Membrane-bound PIP2

Previous studies have implicated PS and PIP2 as regulators of PKCα C2 domain docking to artificial membranes (Corbalan-Garcia et al., 2003; Stahelin et al., 2003; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005). As stated above, the membrane-bound target of the PLCδ1PH domain, PIP2, is specifically enriched in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (Roth, 2004), whereas PS is a constituent of all cellular membranes (van Meer, 1998). Many independent fluorescence studies have observed exclusive targeting of PLCδ1PH domain to plasma membrane, indicating that other intracellular membranes do not contain detectable levels of PIP2 (Roth, 2004). Thus, a specific interaction between the PKCα C2 domain and plasma membrane PIP2 could account for the observed plasma membrane-targeting specificity. To test this hypothesis, we used an established protein-to-membrane FRET assay to quantitate the effect of PIP2 on Ca2+ -dependent binding to phospholipid vesicles in vitro (Nalefski et al., 1997). Specifically, FRET was monitored between four intrinsic tryptophan donors in the PKCαC2 domain and phospholipid vesicles containing 3:1 PC:PS and 5 mol percent dansyl-PE, the latter serving as the FRET acceptor. The vesicles also contained or lacked 6 mol percent PIP2. The presence of PIP2 significantly altered the Ca2+ -dependence of C2 domain docking to vesicles, yielding an 18-fold decrease in the [Ca2+]1/2 (corresponding to an 18-fold affinity increase) for C2 domain docking relative to vesicles lacking PIP2 (Figure 5A). In contrast, PIP2 had no effect on the Ca2+-dependent membrane docking of the C2 domain from cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2αC2; Figure 5B). Together these findings show that PIP2 significantly enhances the Ca2+-mediated recruitment of the PKCα C2 domain to a membrane surface by a Ca2+ signal and suggests that PIP2 binding drives plasma membrane targeting.

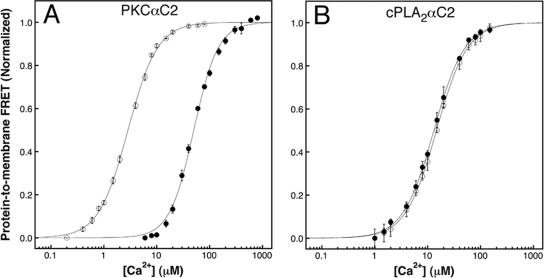

Figure 5.

PIP2 increases the binding affinity of the PKCα C2 domain for phospholipid vesicles. Protein-to-membrane FRET analysis of (A) PKCαC2 domain and (B) cPLA2αC2 domain binding to phospholipid vesicles containing 3:1 PC:PS and 5 mol percent dansyl-PE, either with (•) or without (○) 6 mol percent PIP2. Samples contained 1 μM C2 domain, 100 μM total lipid, 1 mM MgCl2, 140 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 25°C. Data points represent the average ± SD of three independent experiments. Best-fit analysis using the Hill equation (solid lines) yields [Ca2+]1/2 values of 2.9 ± 0.05 μM (+PIP2) and 51 ± 1.5 μM (–PIP2) for PKCα C2 and 15 ± 0.28 μM (+PIP2) and 13 ± 0.29 μM (–PIP2) for cPLA2αC2. Hill coefficients ranged from 1.5 to 1.9 because of the activation of each C2 domain by multiple Ca2+ ions (Kohout et al., 2002).

Intracellular Targeting and Lipid Binding of Hybrid C2 Domains Containing the PKCα C2 Ca2+-binding Loops

Our next aim was to define the structural elements of the C2 domain underlying specific plasma membrane targeting. One possibility is that the CBLs control targeting specificity. For example, our earlier work has shown that the CBLs of a related C2 domain from cPLA2 were sufficient to promote the native intracellular targeting of this C2 domain, which docks to Golgi and ER membranes in vivo (Evans et al., 2004). Furthermore, other studies have suggested that residues located in the PKCα C2 domain CBLs are important in targeting of the isolated C2 domain to the plasma membrane (Conesa-Zamora et al., 2001; Stahelin et al., 2003; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005), and biophysical studies of PKCαC2 docking have demonstrated that the CBLs directly contact the membrane surface (Kohout et al., 2003; Figure 1A).

To assess the role of the PKCαC2 CBLs in targeting and PIP2 recognition, we fused the PKCα C2 CBLs onto a cPLA2α C2 domain scaffold to produce a hybrid domain (cPLA2/PKC_CBLs; Figure 1, A and B). Because the crystal structures for cPLA2αC2 and PKCαC2 are known (Perisic et al., 1998; Verdaguer et al., 1999), it was possible to align homologous structures to produce the hybrids (Figure 1B). Direct comparison of targeting between the cPLA2/PKC-_CBLs hybrid fused to CFP (CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs) and YFP-PKCαC2 revealed Ca2+-dependent translocation of the hybrid from the cytoplasm to a juxtanuclear location, with some binding to the plasma membrane still detectable (Figure 6A and Supplementary Figure 6Avideo). By imaging CFP-PKCαC2_CBLs and TGN38-YFP, a marker for the TGN (Toomre et al., 1999), we established TGN membranes as the target of the juxtanuclear binding (Figure 4B). By contrast, analogous hybrids containing PKCαC2 CBL 1 or CBLs 1 and 3 fused to a cPLA2α C2 domain scaffold failed to exhibit translocation to any membrane in response to Ca2+ mobilization (unpublished data). These findings demonstrate that the isolated PKCαC2 domain CBLs can direct Ca2+-dependent targeting to a limited set of anionic cellular membranes, but are not sufficient to confer PKCαC2-like exclusive targeting to the plasma membrane. Overall, these findings suggest that another structural element required for the native plasma membrane-targeting specificity of the PKCα C2 domain must lie outside the CBLs.

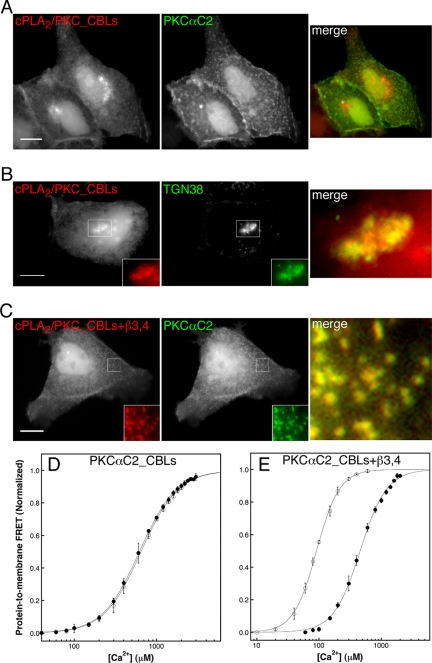

Figure 6.

PKCαC2 β strands 3 and 4 are required for plasma membrane targeting and for Ca2+-dependent binding to PIP2-containing phospholipid vesicles. CFP and YFP image pairs of cells coexpressing (A) CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs and YFP-PKCαC2, (B) CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs and TGN38-YFP, or (C) CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 and YFP-PKCαC2 at 1–2.5 min after stimulation of a cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal by treatment with ionomycin. Insets, enlargements of white-boxed areas and are shown merged on the right of each panel. Scale bars, 10 μm. Results are representative of a minimum of five experiments. Protein-to-membrane FRET analysis of (D) cPLA2/PKC_CBLs and (E) cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 protein binding to phospholipid vesicles with (m) or without (l) 6% PIP2 (see Figure 5 legend for details). Best-fit analysis using the Hill equation (solid lines) yields [Ca2+]1/2 values of 647 ± 11 mM (+PIP2) and 620 ± 5.5 μM (–PIP2) for cPLA2/PKC_CBLs and values of 91.6 ± ± 1.1 mM (+PIP2) and 459 ± 12 mM (–PIP2) for PKCαC2_CBLs+β3–4.

The hybrid C2 domain possessing the three PKCα C2 CBLs was also examined for its ability to recognize PIP2 in the in vitro protein-to-membrane FRET assay. Even in the absence of PIP2, the hybrid required higher Ca2+ levels to drive membrane docking than wild-type PKCα C2 domain (compare Figures 5A and 6D), most likely because of suboptimum orientation of the Ca2+ coordinating residues as previously suggested for other C2 domain hybrids (Gerber et al., 2001). Notably, PIP2 had no effect on the Ca2+-dependence of membrane docking by this hybrid C2 domain, indicating that the CBLs alone are insufficient for PIP2 recognition and suggesting that another region of PKCα C2 domain is involved.

Intracellular Targeting and Lipid Binding of a Hybrid C2 Domain-containing the PKCα C2 Ca2+-binding Loops and the β3–4 Hairpin

A basic region formed by lysine residues in the β-hairpin formed by β strands 3 and 4 has been postulated to coordinate PS or PIP2 in the membrane (Ochoa et al., 2002; Corbalan-Garcia et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Alfaro et al., 2004; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005), and an electron paramagnetic resonance study has demonstrated that this β3–4 hairpin lies in close proximity to the membrane surface (Kohout et al., 2003). To investigate the contribution of the β3–4 hairpin to specific plasma membrane targeting, we constructed another hybrid C2 domain containing the PKCαC2 CBLs and β3–4 hairpin fused to a cPLA2C2 scaffold and coupled to CFP (CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4; Figure 1A). In response to Ca2+ increase, CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 moved from the cytosol and colocalized completely with YFP-PKCαC2 at apical puncta (Figure 6C and Supplementary Figure 6Cvideo). Imaging the translocation of both the CFP-cPLA2/PKC-_CBLs+β3–4 and YFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs hybrid domains in the same cell clearly revealed the essential role of the β3–4 hairpin for specific targeting to the plasma membrane (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary FigureS2video). These results indicate that the β3–4 hairpin of the PKCα C2 domain drives the plasma membrane-targeting specificity of the native domain.

To directly test the role of the β3–4 hairpin in PIP2 recognition, we evaluated the in vitro binding of the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 hybrid protein to vesicles with and without PIP2 in the protein-to-membrane FRET assay. In contrast to the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs hybrid protein, for which PIP2 had no effect on Ca2+-dependent membrane binding (Figure 6D), PIP2 significantly altered the Ca2+-dependent binding of the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs+β3–4 protein to phospholipid vesicles, yielding a fivefold decrease in the [Ca2+]1/2 for binding relative to vesicles lacking PIP2 (Figure 6E). In sum, the data presented here support the view that Ca2+ dependent translocation of PKCα to PIP2-enriched plasma membrane is governed by two membrane-interacting regions of the PKCα C2 domain: the CBL region, which specifically binds Ca2+ and drives membrane association with only limited specificity, and the β 3–4 hairpin, which is required for full plasma membrane specificity and PIP2 recognition.

Intracellular Targeting and Lipid Binding of Mutant PKCα C2 Domains

We next turned our attention to four lysine residues located in the β3–4 hairpin (Figure 1B). Earlier studies have suggested that lysines 197 and 199 in the β3 strand and lysines 209 and 211 in the β4 strand of PKCαC2 are important in Ca2+-independent, PIP2 -dependent binding to vesicles, PS- and PIP2-dependent regulation of PKCα activity in vitro, and membrane residence (Ochoa et al., 2002; Corbalan-Garcia et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Alfaro et al., 2004; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005). The hypothesis that these lysine residues are important in PIP2 recognition predicts that mutations at these positions would weaken membrane-targeting specificity in vivo and lipid-binding affinity in vitro. To test this hypothesis, two mutants were created each containing a pair of substitutions at the critical lysine positions: K197A/K199A and K209A/K211A.

A previous study has shown that the K209A/K211A double mutation has a significantly larger effect than K197A/K199A on PIP2-dependent PKCα kinase activity in vitro and membrane association in vivo (Rodriguez-Alfaro et al., 2004); thus K209A/K211A was selected for fluorescence imaging studies in vivo. First, the mutant PKCα C2 domain-containing K209A/K211A was fused to YFP (YFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A). The resulting mutant targeted primarily to juxtanuclear membranes, with some binding to the plasma membrane still detectable, in response to Ca2+ mobilization. The observed targeting pattern differed significantly from that of CFP-PKCαC2 expressed in the same cell, which exclusively targeted to plasma membrane puncta and patches (Figure 7A and Supplementary Figure 7Avideo). Coimaging YFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A with TGN38-CFP confirmed that the primary target of translocation was the TGN (Supplementary Figure S3A), as previously observed for the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs hybrid lacking the PKCα β3–4 region (Figure 6B). These results suggest that the loss of essential lysines from the β3–4 hairpin inactivates the PIP2 binding site. In this case, targeting is controlled solely by the CBLs and exhibits diminished specificity. This is confirmed by the direct colocalization of YFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A with CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs (Figure 7B and Supplementary Figure 7Bvideo).

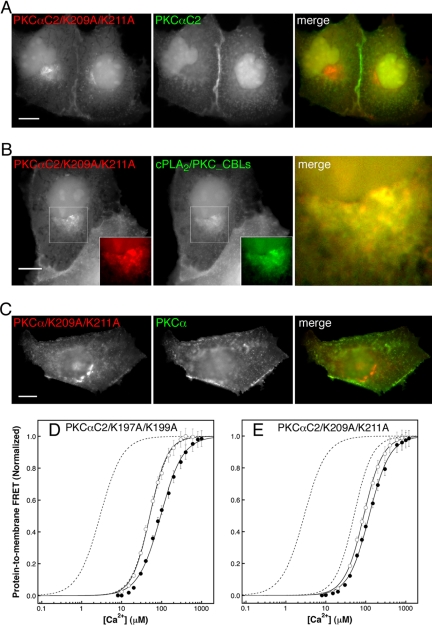

Figure 7.

Lysine residues in β strands 3 and 4 of PKCα C2 domain are required for plasma membrane targeting and for Ca2+-dependent binding to PIP2-containing phospholipid vesicles. CFP and YFP image pairs of cells coexpressing (A) YFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A and CFP-PKCαC2, (B) YFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A and CFP-cPLA2/PKC_CBLs, or (C) YFP-PKCα and CFP-PKCα/K209A/K211A at 55 s after stimulation of a cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal by addition of ionomycin. Insets, enlargements of white-boxed areas and are shown merged on the right of each panel. Scale bars, 10 μm. Results are representative of a minimum of five experiments. Protein-to-membrane FRET analysis of (D) PKCαC2/K197A/K199A protein and (E) PKCαC2/K209A/K211A protein binding to phospholipid vesicles with (•) or without (○) 6% PIP2 (see Figure 5 legend for details). Best-fit analysis using the Hill equation (solid lines) yields [Ca2+]1/2 values of 51 ± 1.3 mM (+PIP2) and 94 ± 4.1 mM (–PIP2) for PKCαC2/K197A/K199A and 89 ± 1.7 mM (+PIP2) and 122 ± 3.2 mM (–PIP2) for PKCαC2/K209A/K211A. Dashed lines for comparison are Hill curves for wild-type PKCαC2 binding from Figure 5A.

To ensure that the targeting results observed for the isolated C2 domain were indicative of full-length PKCα, we also evaluated targeting of a full-length PKCα harboring the K209A/K211A double mutation fused to CFP (CFP-PKCα/K209A/K211A). Targeting of the full-length mutant CFP-PKCα/K209A/K211A to the juxtanuclear region and the plasma membrane in response to Ca2+ increase differed greatly from the exclusively plasma membrane targeting observed for the wild-type, full-length YFP-PKCα (Figure 7C and Supplementary Figure 7Cvideo). As expected, the targeting of the full-length mutant CFP-PKCα/K209A/K211A was coincident with the corresponding mutant C2 domain YFP-PKCαC2/K209A/K211A (Figure S3B and Supplementary FigureS3Bvideo). The full-length mutant, however, exhibited more targeting to the plasma membrane than the C2 domain mutant, suggesting that other membrane-interacting regions of the full-length protein, most likely the C1 domain and/or the pseudosubstrate region, also play roles in targeting when the C2 domain is defective. Nonetheless, our results clearly demonstrate that, as for the isolated C2 domain, mutation of lysine residues 209 and 211 diminishes the targeting specificity of the full-length enzyme.

The hypothesis also predicts that mutation of the essential lysines in the β3–4 hairpin will reduce the effect of PIP2 on Ca2+-dependent vesicle binding in vitro. This prediction is confirmed by the observation that PIP2 has little or no effect on the Ca2+-dependent membrane binding of the PKCαC2/K197A/K199A and PKCαC2/K209A/K211A double mutant C2 domains in the protein-to-membrane FRET assay (Figure 7, D and E). As previously suggested by kinase activity studies (Rodriguez-Alfaro et al., 2004), the K209A/K211A double mutation has a greater effect than K197A/K199A on PIP2-dependent membrane binding. Altogether, these data highlight the importance of basic residues in the β3–4 hairpin for both the specific plasma membrane targeting observed in vivo and the PIP2 binding observed in vitro for the PKCα C2 domain.

DISCUSSION

In this study we examine the contributions of the two membrane-interacting regions of the PKCα C2 domain to 1) Ca2+-dependent, plasma membrane targeting in vivo and 2) Ca2+-dependent, PIP2 binding in vitro. By functionally transplanting the membrane-interacting regions from the PKCα C2 domain to the body of a different C2 domain, we are able to clearly demonstrate the importance of the CBL to general membrane affinity, as well as the importance of the β3–4 hairpin to plasma membrane specificity and PIP2 recognition.

Targeting of PKCα and the Isolated PKCα C2 Domain to Puncta and Patches

Our initial PKCα translocation studies revealed apparent local targeting to apical puncta and to basal patches. Because a number of reports have also observed apical puncta and basal patches with GFP-tagged PLCδ1PH domain and interpret them as focal accumulations of PIP2 (as mentioned above), we explored further the origin of these regions. Using two chemically distinct dyes to uniformly stain the plasma membrane, we find that the puncta and patches are areas containing increased membrane surface area (folds and microvilli), consistent with two other reports (Colarusso and Spring, 2002; van Rheenen and Jalink, 2002) and are not sites of PIP2 and/or lipid raft enrichment. Our observations, however, may be cell-type specific, because other groups using similar membrane dyes have concluded that PLCδ1PH domain and mGAP43 accumulation in localized regions of the plasma membrane is not caused by locally increased membrane area but instead is attributed to rafts (Huang et al., 2004; Golub and Caroni, 2005). Recently, PKCα has been demonstrated to associate with detergent-insoluble fractions in a Ca2+-dependent manner attributed to raft binding (Rucci et al., 2005). However, the correlation between lipid rafts in cells and detergent-insoluble fractions derived from cells continues to be challenged (van Rheenen et al., 2005). Although the plasma membrane puncta and patches observed herein using traditional raft markers are clearly not rafts, we cannot rule out the existence of membrane inhomogeneities such as rafts, which could be too small to be resolved by light microscopy.

Role of CBLs in Targeting to Cell Membranes

Ca2+ binding in the pocket defined by the three CBLs of the PKCα C2 domain has long been recognized as critical for the translocation of PKCα and the isolated PKCα C2 domain to the plasma membrane in cells and for lipid bilayer binding in vitro (Medkova and Cho, 1998; Corbalan-Garcia et al., 1999; Verdaguer et al., 1999; Conesa-Zamora et al., 2001; Stahelin and Cho, 2001; Kohout et al., 2002, 2003; Murray and Honig, 2002). In vitro, and presumably in vivo as well, this translocation involves binding of the Ca2+ -loaded protein to anionic PS headgroups on the membrane surface (Verdaguer et al., 1999; (Evans et al., 2004). The results presented here further demonstrate that the PKCα C2 CBLs, fused to another C2 domain, are sufficient for Ca2+-dependent translocation to anionic cellular membranes and phospholipid vesicles. However, although previous studies have concluded that the CBLs are responsible for exclusive plasma membrane targeting (Stahelin et al., 2003; Marin-Vicente et al., 2005), the present findings indicate that the intracellular targeting mediated by the PKCα C2 CBLs alone is different, and less specific, than the plasma membrane targeting of the native C2 domain. Thus, in the absence of the β3–4 hairpin, the CBLs target primarily to the TGN, with minor binding to the plasma membrane still detectable. It follows that the CBLs alone are not sufficient for specific plasma membrane targeting. This contrasts greatly with the targeting mechanism of another C2 domain, that of cPLA2α, for which the transplanted CBLs were sufficient to confer the native membrane-targeting specificity of cPLA2α (Golgi and ER membranes) onto a hybrid domain (Evans et al., 2004).

Although the PKCα C2 CBLs alone are not sufficient to confer plasma membrane specificity onto a hybrid C2 domain, it should be emphasized that this hybrid domain does exhibit Ca2+-dependent membrane binding and does translocate to a limited set of membrane targets in vivo. Thus, the CBLs of this hybrid domain retain their functional, Ca2+-activated structure and their binding to anionic membranes. Both the TGN and plasma membrane targets of the hybrid domain contain high levels of PS, because the TGN cytoplasmic leaflet is the precursor to the plasma membrane cytoplasmic leaflet. The simplest explanation for the observed targeting of the hybrid domain to these membranes is that the transplanted CBLs retain their native interaction with membrane-bound PS headgroups, thereby ensuring translocation primarily to cellular membranes possessing high PS densities. Clearly, however, this weakened specificity is insufficient to ensure exclusive translocation to the plasma membrane.

Role of the Basic Region in the β3–4 Hairpin in Targeting to Cell Membranes

Biophysical studies have shown that the β-hairpin formed by β strands 3 and 4 of the PKCα C2 domain lies close to the plasma membrane because of a nearly parallel orientation of the domain relative to the membrane (Kohout et al., 2003), similar to earlier predictions (Verdaguer et al., 1999). Further structural studies of PKCαC2 complexed with Ca2+ and soluble PS have revealed a basic region comprised of four lysine residues in the β3–4 hairpin that endow the region with a strong positive charge (Ochoa et al., 2002). Specific interactions between K209 and K211 and the soluble PS have been observed in a crystal structure (Ochoa et al., 2002). Moreover, K209 and K211 have been implicated in studies of PIP2 binding (Corbalan-Garcia et al., 2003), whereas both PS- and PIP2-dependent enzyme activation is reduced by mutation of basic region lysines (Corbalan-Garcia et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Alfaro et al., 2004). These studies point to the basic region of the β3–4 hairpin as a second functional lipid-binding site distinct from the CBLs. The imaging experiments presented herein directly demonstrate that the β3–4 hairpin and its interaction with PIP2 are critical for targeting to the plasma membrane. Thus, addition of the PKCα β3–4 hairpin to the cPLA2/PKC_CBLs hybrid yields native PKCα C2-like targeting to the PIP2-rich plasma membrane inner leaflet. Furthermore, protein-to-membrane FRET studies conclusively demonstrate that the β3–4 hairpin is critical for recognition of PIP2 by the hybrid domains. The importance of this second membrane-interacting site in plasma membrane targeting and PIP2 recognition is further corroborated by our experiments where mutation of two lysine residues in the basic region, K209 and K211, promoted targeting to primarily the TGN rather than to plasma membrane. Notably, mutation of the basic region in the β3–4 hairpin of the PKCα C2 domain gives the same pattern of translocation as the hybrid C2 domain possessing the PKCαC2 CBLs but lacking the β3–4 hairpin. Moreover, our in vitro FRET studies show that PIP2 binding is greatly affected by mutation of lysines in either the β3or β4 strands. Overall, the results clearly implicate the basic region in the β3–4 hairpin as being a second site necessary for proper targeting to the plasma membrane and recognition of PIP2.

The CBLs and Basic Regions Serve a Coincidence Detection Function

Here we have provided evidence that two membrane-interacting sites of the PKCα C2 domain, the CBLs and the basic region of the β3–4 hairpin, are both involved in Ca2+-mediated targeting to PS and PIP2 on the cytoplasmic surface of the plasma membrane, respectively. The present findings show that Ca2+ binding to the CBLs is both necessary and sufficient to drive membrane binding in vivo and in vitro, but is not sufficient for specific plasma membrane targeting. By contrast, the interaction of the basic region of the β3–4 hairpin with PIP2, although not sufficient to drive translocation in the absence of Ca2+ binding to the CBLs, is required for specific targeting via its interaction with the PIP2-rich plasma membrane. Ca2+ binding to the CBLs is needed to provide an electrostatic driving force for anionic membrane docking (Nalefski et al., 1997; Evans et al., 2004) and could also be needed to rearrange the β3–4 hairpin to yield a conformation suitable for PIP2 binding.

The presence of these two functional regions is proposed to generate a Ca2+-activated, PS/PIP2 coincidence detection function to the PKCα C2 domain, and, by extension, to the enzyme as a whole. Ca2+-triggered targeting to PS and PIP2 in plasma membrane could play an important physiological role by directing membrane docking to regions of the plasma membrane containing high densities of diacylglycerol created by phospholipase C-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2, which binds to the C1 domain of PKCα and is required for its full enzymatic activity. For example, it has been proposed that PIP2 and certain proteins, some of which are known PKCα effector proteins, are enriched in lipid rafts that are too small or closely spaced to be detected by fluorescence microscopy (Hope and Pike, 1996; Laux et al., 2000; Uchino et al., 2004). If such PIP2-enriched rafts exist they could serve as organizing centers for signaling complexes in which PKCα lies in close proximity to its substrate proteins. Moreover, modulation of the PIP2 spatio-temporal distribution could play an important role in PKCα regulation. Further in vivo studies at higher spatial resolution or biochemical studies of isolated rafts are needed to investigate these possibilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J.-W. Soh for the human PKCα, M. Katan EGFP-PLCδ1PH domain, and K. Simons for TGN38-CFP and TGN38-YFP. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM063235 (J.J.F.), GM066147 (D.M.), and HL061378 and HL034303 (C.C.L.).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05–06–0499) on October 19, 2005.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Arni, S., Keilbaugh, S. A., Ostermeyer, A. G., and Brown, D. A. (1998). Association of GAP-43 with detergent-resistant membranes requires two palmitoylated cysteine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28478–28485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J., Tucker, W. C., and Chapman, E. R. (2004). PIP2 increases the speed of response of synaptotagmin and steers its membrane-penetration activity toward the plasma membrane. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla, T., and Varnai, P. (2002). Visualizing cellular phosphoinositide pools with GFP-fused protein-modules. Science's Stke [Electronic Resource]: Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment 2002, PL3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N., and Bourne, P. E. (2000). The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsover, S. R., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., and Corbalan-Garcia, S. (2003). Role of the Ca2+/phosphatidylserine binding region of the C2 domain in the translocation of protein kinase Calpha to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10282–10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F. D., Rozelle, A. L., Yin, H. L., Balla, T., and Donaldson, J. G. (2001). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and Arf6-regulated membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 154, 1007–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colarusso, P., and Spring, K. R. (2002). Reticulated lipid probe fluorescence reveals MDCK cell apical membrane topography. Biophys. J. 82, 752–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa-Zamora, P., Lopez-Andreo, M. J., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., and Corbalan-Garcia, S. (2001). Identification of the phosphatidylserine binding site in the C2 domain that is important for PKC alpha activation and in vivo cell localization. Biochemistry 40, 13898–13905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, R. A. (1994). Methods for Protein Analysis: A Practical Guide to Laboratory Protocols, New York: Chapman and Hall.

- Corbalan-Garcia, S., García-García, J., Rodríguez-Alfaro, J. A., and Gómez-Fernández, J. C. (2003). A new phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-binding site located in the C2 domain of protein kinase Cα J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4972–4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbalan-Garcia, S., Rodríguez-Alfaro, J. A., and Gómez-Fernández, J. C. (1999). Determination of the calcium-binding sites of the C2 domain of protein kinase Cα that are critical for its translocation to the plasma membrane. Biochem. J. 337, 513–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens, L., Parker, P. J., Rhee, L., Yang-Feng, T. L., Chen, E., Waterfield, M. D., Francke, U., and Ullrich, A. (1986). Multiple, distinct forms of bovine and human protein kinase C suggest diversity in cellular signaling pathways. Science 233, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. H., Gerber, S. H., Murray, D., and Leslie, C. C. (2004). The calcium binding loops of the cytosolic phospholipase A2 C2 domain specify targeting to Golgi and ER in live cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, S. H., Rizo, J., and Sudhof, T. C. (2001). The top loops of the C(2) domains from synaptotagmin and phospholipase A(2) control functional specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32288–32292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub, T., and Caroni, P. (2005). PI(4,5)P2-dependent microdomain assemblies capture microtubules to promote and control leading edge motility. J. Cell Biol. 169, 151–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbeck, O., Baird, G. S., Campbell, R. E., Zacharias, D. A., and Tsien, R. Y. (2001). Reducing the environmental sensitivity of yellow fluorescent protein. Mechanism and applications. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29188–29194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope, H. R., and Pike, L. J. (1996). Phosphoinositides and phosphoinositide-utilizing enzymes in detergent-insoluble lipid domains. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 843–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S., Lifshitz, L., Patki-Kamath, V., Tuft, R., Fogarty, K., and Czech, M. P. (2004). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-rich plasma membrane patches organize active zones of endocytosis and ruffling in cultured adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9102–9123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J. H., and Misra, S. (2000). Signaling and subcellular targeting by membrane-binding domains. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 49–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, T., and Takenawa, T. (2002). Phosphoinositide-binding domains: functional units for temporal and spatial regulation of intracellular signalling. Cell Signal. 14, 733–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout, S. C., Corbalan-Garcia, S., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., and Falke, J. J. (2003). C2 domain of protein kinase Calpha: elucidation of the membrane docking surface by site-directed fluorescence and spin labeling. Biochemistry 42, 1254–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout, S. C., Corbalan-Garcia, S., Torrecillas, A., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., and Falke, J. J. (2002). C2 domains of protein kinase C isoforms alpha, beta, and gamma: activation parameters and calcium stoichiometries of the membrane-bound state. Biochemistry 41, 11411–11424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwik, J., Boyle, S., Fooksman, D., Margolis, L., Sheetz, M. P., and Edidin, M. (2003). Membrane cholesterol, lateral mobility, and the phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent organization of cell actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13964–13969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux, T., Fukami, K., Thelen, M., Golub, T., Frey, D., and Caroni, P. (2000). GAP43, MARCKS, and CAP23 modulate PI(4,5)P(2) at plasmalemmal rafts, and regulate cell cortex actin dynamics through a common mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1455–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, M. A. (2003). Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic 4, 201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Vicente, C., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., and Corbalan-Garcia, S. (2005). The ATP-dependent membrane localization of PKCα is regulated by Ca2+ influx and PtdIns(4,5)P2 in differentiated PC12 Cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2848–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medkova, M., and Cho, W. (1998). Mutagenesis of the C2 domain of protein kinase C-α. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17544–17552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, D., and Honig, B. (2002). Electrostatic control of the membrane targeting of C2 domains. Mol. Cell 9, 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalefski, E. A., Slazas, M. M., and Falke, J. J. (1997). Ca2+-signaling cycle of a membrane-docking C2 domain. Biochemistry 36, 12011–12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka, Y. (1995). Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 9, 484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea, E., and Meyer, T. (1998). Protein kinase C as a molecular machine for decoding calcium and diacylglycerol signals. Cell 95, 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, W. F., Corbalan-Garcia, S., Eritja, R., Rodriguez-Alfaro, J. A., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., Fita, I., and Verdaguer, N. (2002). Additional binding sites for anionic phospholipids and calcium ions in the crystal structures of complexes of the C2 domain of protein kinase calpha. J. Mol. Biol. 320, 277–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perisic, O., Fong, S., Lynch, D. E., Bycroft, M., and Williams, R. L. (1998). Crystal structure of a calcium-phospholipid binding domain from cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 1596–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raucher, D., Stauffer, T., Chen, W., Shen, K., Guo, S., York, J. D., Sheetz, M. P., and Meyer, T. (2000). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate functions as a second messenger that regulates cytoskeleton-plasma membrane adhesion. Cell 100, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo, J., and Sudhof, T. C. (1998). C2-domains, structure and function of a universal Ca2+-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15879–15882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Alfaro, J. A., Gomez-Fernandez, J. C., and Corbalan-Garcia, S. (2004). Role of the lysine-rich cluster of the C2 domain in the phosphatidylserine-dependent activation of PKCalpha. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, M. G. (2004). Phosphoinositides in constitutive membrane traffic. Physiol. Rev. 84, 699–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucci, N., Digiacinto, C., Orru, L., Millimaggi, D., Baron, R., and Teti, A. (2005). A novel protein kinase Cα-dependent signal to ERK1/2 activated by αVβ3 integrin in osteoclasts and in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. J. Cell Sci. 118, 3263–3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, N., Sasaki, K., Ikegaki, N., Shirai, Y., Ono, Y., and Saito, N. (1997). Direct visualization of the translocation of the gamma-subspecies of protein kinase C in living cells using fusion proteins with green fluorescent protein. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1465–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali, A., and Blundell, T. L. (1993). Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindyalov, I. N., and Bourne, P. E. (1998). Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 11, 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahelin, R. V., and Cho, W. (2001). Roles of calcium ions in the membrane binding of C2 domains. Biochem. J. 359, 679–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahelin, R. V., Rafter, J. D., Das, S., and Cho, W. (2003). The molecular basis of differential subcellular localization of C2 domains of protein kinase C-alpha and group IVa cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12452–12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, T. P., Ahn, S., and Meyer, T. (1998). Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr. Biol. 8, 343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall, E. G., Spector, I., Pentyala, S. N., Bitter, I., and Rebecchi, M. J. (2000). Dynamics of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in actin-rich structures. Curr. Biol. 10, 743–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruel, M. N., and Meyer, T. (2000). Translocation and reversible localization of signaling proteins: a dynamic future for signal transduction. Cell 103, 181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomre, D., Keller, P., White, J., Olivo, J.C., and Simons, K. (1999). Dual-color visualization of trans-Golgi network to plasma membrane traffic along microtubules in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 112(Pt 1), 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, M., Sakai, N., Kashiwagi, K., Shirai, Y., Shinohara, Y., Hirose, K., Iino, M., Yamamura, T., and Saito, N. (2004). Isoform-specific phosphorylation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 by protein kinase C (PKC) blocks Ca2+ oscillation and oscillatory translocation of Ca2+-dependent PKC. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2254–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer, G. (1998). Lipids of the Golgi membrane. Trends Cell Biol. 8, 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen, J., Achame, E. M., Janssen, H., Calafat, J., and Jalink, K. (2005). PIP2 signaling in lipid domains: a critical re-evaluation. EMBO J. 24, 1664–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen, J., and Jalink, K. (2002). Agonist-induced PIP(2) hydrolysis inhibits cortical actin dynamics: regulation at a global but not at a micrometer scale. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3257–3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai, P., and Balla, T. (1998). Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J. Cell Biol. 143, 501–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdaguer, N., Corbalan-Garcia, S., Ochoa, W. F., Fita, I., and Gomez-Fernandez, J. C. (1999). Ca(2+) bridges the C2 membrane-binding domain of protein kinase Calpha directly to phosphatidylserine. EMBO J. 18, 6329–6338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.