Abstract

A simple method for the detection of sequence- and structural-selective ligand binding to nucleic acids is described. The method is based on the commonly used thermal denaturation method in which ligand binding is registered as an elevation in the nucleic acid melting temperature (Tm). The method can be extended to yield a new, higher -throughput, assay by the simple expediency of melting designed mixtures of polynucleotides (or oligonucleotides) with different sequences or structures of interest. Upon addition of ligand to such mixtures at low molar ratios, the Tm is shifted only for the nucleic acid containing the preferred sequence or structure. Proof of principle of the assay is provided using first a mixture of polynucleotides with different sequences and, second, with a mixture containing DNA, RNA and two types of DNA:RNA hybrid structures. Netropsin, ethidium, daunorubicin and actinomycin, ligands with known sequence preferences, were used to illustrate the method. The applicability of the approach to oligonucleotide systems is illustrated by the use of simple ternary and binary mixtures of defined sequence deoxyoligonucleotides challenged by the bisanthracycline WP631. The simple mixtures described here provide proof of principle of the assay and pave the way for the development of more sophisticated mixtures for rapidly screening the selectivity of new nucleic acid binding compounds.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleic acids are an important target for new therapeutic agents (1–4). Two fundamental strategies exist for targeting nucleic acids. The first is to target specific sequences that are vital for the control of gene expression (e.g. transcription factor binding sites) with small molecule inhibitors (5–7). This strategy has seen success with the development of sequence-specific polyamides (6,8,9) and, more recently, with antigene PNA molecules (10). A second strategy is to target noncannonical structures that may regulate gene activity. Daunorubicin and its synthetic enantiomer, for example, can act as mutual allosteric effectors to switch DNA between right- and left-handed forms (11). G-quadruplexes are of intense interest as targets and have been implicated as important structural elements in both the biology of telomeres and in the regulation of gene expression (3,12,13). Small molecules that target G-quadruplexes and that can regulate c-myc oncogene expression have recently been reported (14–18).

The evolution of new tools for the study of sequence- and structural-selective ligand binding is important for efficient drug discovery. Chemical and enzymatic footprinting methods revolutionized studies of sequence-selective recognition of DNA by small molecules, enabling identification of ligand binding sites to base pair resolution (19–21). Competition dialysis methods that allowed for rather precise inferences of ligand base- and sequence-specificity actually predated footprinting (22,23), but saw little application in part because of the low-throughput nature of the assay. The competition dialysis method was recently revived and expanded to provide a rapid means of quantitatively evaluating ligand sequence- and structural-selectivity by using an array of nucleic acid samples (24–27). Thermal denaturation methods provide a thermodynamically sound approach for quantifying drug–nucleic acid interactions (28–31). Thermal denaturation is especially powerful for the characterization of ligands with ultratight binding affinity (32). A rapid and frugal thermal denaturation assay using molecular beacons was devised to study ligand interactions with duplex, triplex and quadruplex nucleic acids (33). While thermal denaturation methods are powerful, rigorous and readily automated, they are hampered by comparatively low-throughput. Samples are generally run serially, and a typical melting curve takes several hours to accumulate. Comparison of ligand binding with many sequences or structures is thus time consuming.

We report a simple new thermal denaturation assay that greatly facilitates comparison of ligand binding with different nucleic acid sequences or structures. The assay is based on the simple expediency of melting mixtures of polynucleotides with different sequences or structures whose melting temperatures are well resolved. Addition of ligand to such mixtures at appropriate molar ratios results in a shift of the melting temperature of the nucleic acid containing the preferred structure or sequence, providing a clear indication of ligand selectivity. We provide proof of principle of the assay concept for two cases, first with mixtures to test sequence selectivity and second with a mixture to test structural selectivity. The applicability to oligonucleotide mixtures is also demonstrated. We describe here assays that contain 4–5 sequences or structures. The concept is robust, however, and can potentially be expanded to include large numbers of samples of particular interest.

Additional comments concerning the strategy and design of the assay are needed. Melting of nucleic acids in the presence of ligands is complex (29,30). The apparent Tm shift has a simple quantitative meaning only under conditions where the nucleic acid lattice is fully saturated with ligand. At ligand concentrations where the lattice is not fully saturated, melting curves become multiphasic due to ligand redistribution, and the shift in Tm has no simple interpretation or meaning. By design, the assay described here utilizes low molar ratios of ligand, where the lattice is far from saturation. This is opposite from the typical experimental design usually used in melting experiments (31), but is an essential condition for visualizing sequence or structural selectivity. Sequence- or structural-selective binding is most clearly manifested in the limit as the binding ratio approaches zero (22,23). Our intent is to provide an assay that provides a rapid, qualitative demonstration of selective binding, one that clearly shows a Tm shift for the melting of the preferred nucleic acid. The assay is, by design, optimized for demonstrating selectivity in binding and is not intended to be used for quantitative analysis of Tm shifts. Once the assay identifies interesting types of selective binding, rigorous biophysical studies can follow to characterize the thermodynamics of binding quantitatively. The situation is analogous to early footprinting methodologies which focused on the qualitative identification of preferred binding sequences rather than on quantitative analysis of binding affinities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sequence polynucleotides

[Poly(dA–dT)]2, Poly(dA)·poly (dT), Poly(dA–dC)·poly(dG–dT), Poly(dC)·poly (dG) and [Poly(dC–dG)]2 were purchased from Amersham Biosciences, Co. (Piscataway, NJ) and were used without further purification. Concentrations of nucleic acid samples were determined by UV absorbance measurements using the molar extinction coefficients (expressed in terms of phosphate) shown in Table 1. All polymer samples were prepared in BPE/4 buffer (1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.25 mM Na2EDTA, pH = 7.0). For preparation of polynucleotide mixtures, equal molar concentrations [typically 20–40 µM (bp)] of five polymers were added to the desired volume of buffer solution.

Table 1.

Polynucleotide and oligonucleotide samples used

| Mixture | Nucleic acid | λ (nm) | ɛa (M−1 cm−1) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequenceb | [Poly(dA–dT)]2 | 262 | 6600 | 32.3 |

| Poly(dA)·poly(dT) | 260 | 6000 | 39.7 | |

| Poly(dA–dC)·poly(dG–dT) | 258 | 6500 | 63.2 | |

| Poly(dC)·poly(dG) | 253 | 7400 | 73.1 | |

| [Poly(dC–dG)]2 | 254 | 8400 | 87.8 | |

| Structurec | Poly(dA)·poly(dT) | 260 | 6000 | 63.2 |

| Poly(rA)·poly(rU) | 260 | 7140 | 52.6 | |

| Poly(dA)·poly(rU) | 257 | 6500 | 38.6 | |

| Poly(rA)·poly(dT) | 260 | 6230 | 60 | |

| Oligonucleotided | 1. T2 (CC)10 T2 + T2 (GG)10 T2 | 260 | 133,148 | 51 |

| 260 | 270 478 | |||

| 2. T2 (AC)10 T2 + T2 (GT)10 T2 | 260 | 197 120 | 63.9 | |

| 260 | 237 000 | |||

| 3. T2 (AG)10 T2 + T2 (CT)10 T2 | 260 | 263 907 | 71.9 | |

| 260 | 185 789 |

aConcentration units of the extinction coefficient are expressed in terms bases for polynucleotides or strands for oligonucleotides. The molar extinction coefficients for single-stranded oligonucleotides were determined by means of a colorimetric phosphate assay (46).

bThe concentration of each polynucleotide in this mixture is 40 µM (bp). The experiments were conducted in a buffer containing 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4 and 0.25 mM Na2EDTA at pH 7.0.

cThe concentration of each polynucleotide is 10 µM (bp). The experiments were conducted in a buffer containing 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.25 mM Na2EDTA and 46.25 mM NaCl at pH 7.0.

dThe concentration of each oligonucleotide is 2 µM (strand). The experiments were conducted in a buffer containing 6 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM Na2EDTAand 185 mM NaCl at pH 7.0.

Structural polynucleotides

Poly(dA) and poly(dT) were purchased from Amersham Biosciences, Co. (Piscataway, NJ). Poly(rA) and Poly(U) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO). These synthetic polynucleotides were used without further purification. Concentrations of nucleic acid samples were determined by UV absorbance measurements using molar extinction coefficients (in terms of phosphate) of 8600 M−1 cm−1 at 257 nm for poly(dA), 8520 M−1 cm−1 at 264 nm for poly(dT), 9800 M−1 cm−1 at 258 nm for poly(rA), 9350 M−1 cm−1 at 260 nm for poly(U), respectively. To prepare DNA, RNA and DNA:RNA hybrid structures, equimolar amounts of single-stranded polymers were mixed with their complementary strand in BPES/4 buffer (1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.25 mM Na2EDTA and 46.25 mM NaCl, pH = 7.0). Samples were heated at 90°C for 3 min followed by slow cooling to room temperature.

Oligodeoxynucleotides

Synthetic 24 nt deoxyoligonucleotides, containing simple CC/GG, AC/GT and AG/CT dinucleotide sequences were purchased from Oligos Etc., Inc. (Wilsonville, OR). The sequences and molar extinction coefficient (expressed in terms of strands) were listed in Table 1. These oligomers were stored as concentrated stock solutions in water and were diluted to working concentrations immediately before use. For the preparation of double-stranded oligomers, equal molar amounts of single-stranded deoxyoligonucleotides were mixed with their complementary strand in BPES buffer (6 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM Na2EDTA and 0.185 M NaCl, pH = 7.0). Subsequently, the mixtures were heated at 90°C for 3 min followed by slow cooling to room temperature prior to the melting experiments.

Ligands

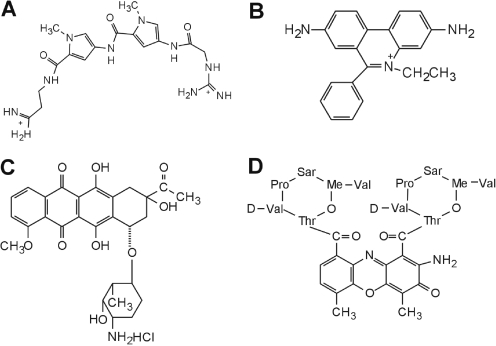

Ethidium bromide, daunomycin and actinomycin D were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Netropsin was purchased from Serva Feinbiochemica (Heidelberg, Germany). The structures of the ligands are shown in Figure 1. WP631 was purchased from EMD Biosciences, Inc. Ligands were used without further purification and prepared in distilled water and stored at −20°C. Drug concentrations were determined spectophotometrically.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds used for melting studies. (A) Netropsin, (B) ethidium, (C) daunorubicin and (D) actinomycin D.

Thermal denaturation assay

A Jasco V-550 UV/Vis (Tokyo, Japan) spectrophotometer equipped with a thermoelectric temperature controller was used to obtain thermal denaturation data. One centimeter pathlength quartz cuvettes with Teflon stoppers were used. All sample mixtures were fully equilibrated at room temperature following addition of ligand and were subsequently heated over the range of 20–98°C at a rate of 1°C/min while the absorbance was continuously monitored at 260 nm. Primary data were transferred to the graphics program Origin (Microcal, Inc.) for plotting and analysis.

Competition dialysis

Competition dialysis experiments were carried out as described previously (24–27). The experiments were carried out in BPES buffer consisting of 6 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM Na2EDTA and 0.185 M NaCl (pH 7.0). Nucleic acid samples including four different structures (volume of 200 µl at identical concentration of 75 µM bp) were dialyzed against 200 ml dialysate containing 1 µM netropsin or ethidium.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Assay for sequence selectivity

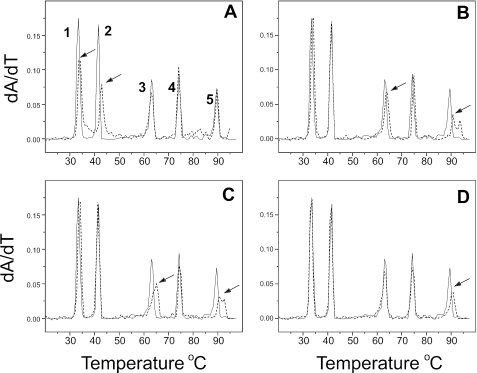

An assay for base and sequence selectivity was devised by preparing an equimolar mixture of [Poly(dA–dT)]2, Poly(dA)·poly (dT), Poly(dA–dC)·poly(dG–dT), Poly(dC)·poly(dG) and [Poly(dC–dG)]2. The Tm values of these duplexes are well separated (Table 1). Collectively, the polynucleotide mixture contains eight of the ten unique dinucleotide steps (AA = TT, AT, TA, AC, CA, GG = CC, GC, CG), and eight of the 32 unique triplet sequences (AAA, GGG, ATA, TAT, GCG, CGC, ACA, CAC). Figure 2 shows the results of addition of the compounds shown in Figure 1 to the mixture. Low molar ratios of compound (∼0.01 drug/bp) were added to the mixture because such conditions are optimal for the selection of a particular binding site from the mixture. Netropsin (Figure 1A) shows a clear preference for binding to poly(dA)·poly (dT) and to a lesser extent, [poly(dA–dT)]2 (Figure 2A), as is evident from the shifts in peaks 2 and 1. This result is fully consistent with the known preference of this groove binder for AT-rich sequences revealed in the very first footprinting studies (19,21). Competition dialysis also revealed the strong preference of netropsin for [Poly(dA–dT)]2 and Poly(dA)·poly (dT), along with a general preference for AT-rich natural DNA samples (25).

Figure 2.

Sequence selectivity revealed by melting studies of polynucleotide mixtures. Each panel shows the melting of a mixture of [poly(dA–dT)]2 (peak 1), poly(dA)•poly(dT) (peak 2), poly(dA–dC)•poly(dG–dT) (peak 3), poly(dG)•poly(dC) (peak 4) and [poly(dG–dC)2 (peak 5) as the solid black line. The concentration of each polynucleotide is 40 µM (bp); total polynucleotide concentration is 200 µM (bp). The dashed line in each panel shows the effect of additions of low molar ratios of each of the compounds shown in Figure 1. The arrows indicate the peaks that are altered by addition of the compound. (A) Netropsin at 2 µM; (B) ethidium at 2 µM; (C) daunorubicin at 2 µM; (D) actinomycin D at 1.5 µM.

We emphasize here that, by design, the assay uses a single, low molar ratio of added ligand, conditions that maximize the manifestation of selective binding. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the effects of increasing the molar ratio of netropsin on the melting of the polynucleotide mixture. As can be seen in that figure, as the concentration of netropsin increases, the Tm values for the melting of the two AT containing polynucleotides increases, but that less specific binding to the remaining three polynucleotides also becomes evident. Such behavior is to be expected as the increased free ligand concentration drives the weaker, non-specific binding to the less preferred sequences.

Ethidium (Figure 1B) is widely, but erroneously, thought to lack sequence selectivity. It can, in fact, discriminate between sequences as revealed in low-temperature footprinting experiments (34). From an analysis of the changes in patterns of digestion by DNAase I, Fox and Waring deduced that ethidium binds best to regions of mixed nucleotide sequence, especially those containing alternating purines and pyrimidines. Exactly that preference is revealed in Figure 2B. Tm shifts are evident for only poly(dA–dC)·poly(dG–dT) and [Poly(dC–dG)]2.

The anticancer agent daunorubicin (Figure 1C) binds preferentially (but not exclusively) to triplet sequences in which an AT base pair is flanked by adjacent GC base pairs (35–37). Daunorubicin shows a general preference for GC-rich DNA with an alternating purine-pyrimidine sequence (22). Such preferences are observed in Figure 2C, where daunomycin elevates the Tm of poly(dA–dC)·poly(dG–dT) and [Poly(dC–dG)]2.

Actinomycin binds selectively to 5′GpC steps in duplex DNA (19,21,38). That sequence preference is clearly observed in Figure 2D, where actinomycin only alters the Tm of [Poly(dC–dG)]2.

Collectively, the data shown in Figure 2 confirm the utility of the melting of mixtures assay. The results obtained are fully consistent with the known sequence preferences of the standard compounds used for validation of the assay. There are significant advantages of the thermal denaturation assay over both footprinting and competition dialysis methods. Both footprinting and dialysis are time consuming, with at least 24 h needed in each case to execute the experiment and process the data. Competition dialysis, in its simplest form, requires that ligands possess convenient absorbance or fluorescence signals for concentration determinations. The thermal denaturation assay described here requires no signal from the ligand and can be completed in a few hours with real-time data display. As a standard spectrophotometric assay, the method is clearly amenable to automation and multiplexing.

We caution that, by design, the absolute values of Tm shift in this assay are not of primary importance in this assay, and in fact have no simple quantitative meaning. The conditions of the assay are such that the nucleic acid lattice is not saturated by ligand, consequently melting curves in the presence of ligand are expected to be broad and multiphasic (29,30). Nonetheless, the shift in Tm unambiguously reports the binding to the most preferred nucleic acid sequence.

Oligonucleotide-based assay

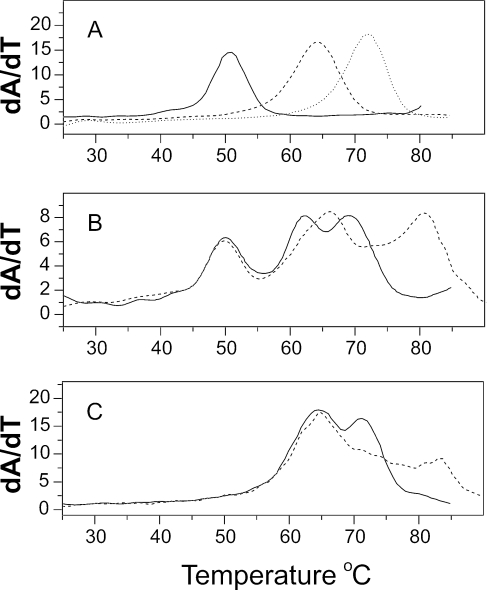

Figure 3 shows results for a simple oligonucleotide-based assay. The polynucleotide assay for sequence selectivity is hampered by the availability of all desired sequences. Deoxyoligonucleotides of any desired sequence can be synthesized, imparting great flexibility in the design of sequence mixtures for specific purposes. A potential disadvantage of an oligonucleotide assay is in the width of the individual melting transitions, which may adversely affect the resolution of melting temperatures. Figure 3, however, provides encouraging proof of principle.

Figure 3.

Melting of deoxyoligonucleotide mixtures. (A). Melting of (T2G20T2)• (T2C20T2) (black line), (T2(AC)10T2)• (T2(GT)10T2) (dashed line) and (T2(AG)10T2)• (T2(CT)10T2) (dotted line). All samples were at 2 µM duplex concentration. (B). Melting of a mixture of the three deoxyoligonucleotides in (A) in the absence (black line) or presence (dashed line) of the bisanthracycline WP631 (32). Each deoxynucleotide in the mixture was at a concentration of 0.67 µM duplex, for a total duplex concentration of 2 µM. WP631 was add to a final concentration of 1.6 µM. (C). Melting of a binary mixture (4 µM total duplex) of (T2(AC)10T2)• (T2(GT)10T2) and (T2(AG)10T2)• (T2(CT)10T2) alone (black line) or in the presence of 1.6 µM WP631 (dashed line).

Figure 3A shows the melting of three 24 bp designed duplexes, T2 (CC)10 T2 · T2 (GG)10 T2, T2 (AC)10 T2 · T2 (GT)10 T2 and T2 (AG)10 T2 · T2 (CT)10 T2, whose Tm values are, respectively, 51, 63.9 and 71.9°C. Figure 3B (black line) shows a mixture of these three duplexes. The peak positions are lowered relative to panel A because of a decrease in duplex concentration from 2 to 0.67 µM. The melting transitions of the three duplexes remain well resolved in the mixture. Upon addition of the bisdaunorubicin WP631 (Figure 3B, dashed line), melting of T2 (CC)10 T2 · T2 (GG)10 T2 is unaltered, while the melting temperatures of both T2 (AC)10 T2 · T2 (GT)10 T2 and T2 (AG)10 T2 · T2 (CT)10 T2 are increased. WP631 clearly prefers the sequences with mixed AT/GC composition. There is a greater increase in the Tm of the AG sequence, suggesting that a nonalternating purine-purine arrangement is preferred over an alternating purine-pyrimidine sequence. Results using a binary mixture of T2 (AC)10 T2 · T2 (GT)10 T2 and T2 (AG)10 T2 · T2 (CT)10 T2 confirm that conclusion (Figure 3C). The results in Figure 3C indicate that WP631 can selectively stabilize the purine-purine sequence at low molar ratios where binding preferences are most clearly manifested.

These results show that oligonucleotide mixtures are of utility for studies of sequence selectivity. Simple binary and ternary mixtures were deliberately chosen to illustrate the potential of the method. There is no reason to prevent extension of the method to more complicated mixtures. The advantage of the oligonucleotide system is that any sequences of interest can be synthesized and studied. Minor disadvantages are that the width of oligonucleotide melting transitions adversely affects resolution, and melting temperatures are more dependent upon strand concentration than is the case for polynucleotides.

Assay for structural selectivity

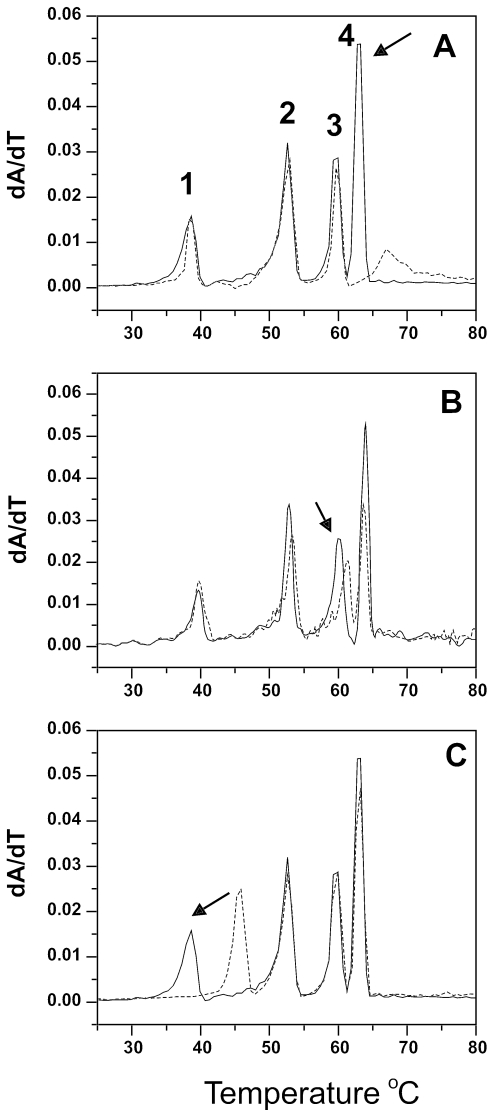

A mixture was made to study ligand selectivity for four different structures, DNA, RNA and two types of DNA:RNA hybrids. In this mixture, DNA is represented by poly(dA)·poly(dT), RNA by poly(rA)·poly(rU), hybrid I by poly(dA)·poly(rU) and hybrid II by poly(rA)·poly(dT). DNA:RNA hybrids are structures of profound biological importance and are an emerging target for drug design efforts (39–41). Results are shown in Figure 4.

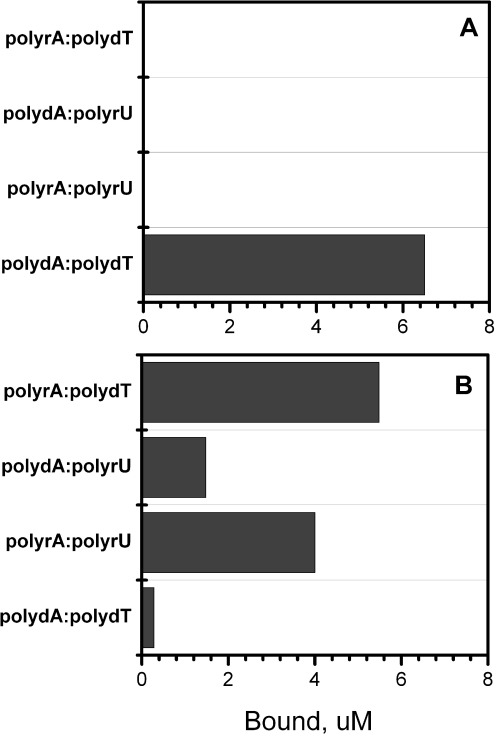

Figure 4.

Structural selectivity revealed by melting studies of polynucleotide mixtures. Each panel shows the melting of a mixture of DNA [poly(dA)·poly (dT); peak 4], RNA [poly(rA)•poly (rU); peak 2], a DNA:RNA hybrid [poly (dA)•poly (rU); peak 1] and an RNA:DNA hybrid [poly(rA)•poly (dT); peak 3] as the solid black line. The concentration of each polynucleotide structure was 10 µM (bp); total polynucleotide concentration is 40 µM (bp). The dashed line in each panel shows the effect of addition of ligand. (A). Netropsin at 1.6 µM. (B) Ethidium at 1.5 µM. (C) A semi-synthetic derivative of the natural product β-lapachone (45) at 5 µM.

The classical groove-binder netropsin showed a clear preference for DNA as represented by poly(dA)·poly(dT), as was expected. Netropsin is known to convert non-B-DNA structures back to a standard B-form that contains the preferred minor groove geometry to which it binds most avidly (42,43). Netropsin does not bind to A-form RNA (44). Competition dialysis (Figure 5A) was used to confirm the structural preference of netropsin to validate the results of the melting mixture assay.

Figure 5.

Results of competition dialysis experiments. The amount of netropsin (A) or EB (B) bound to each structure is shown as a bar graph. Nucleic acid samples (200 µl at identical concentration of 75 µM bp) were dialyzed against 200 ml dialysate containing 1 µM ligand. The experiments were carried out in BPES buffer consisting of 6 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM Na2EDTA and 0.185 M NaCl (pH 7.0).

Ethidium was previously shown by competition dialysis to bind preferentially to an RNA:DNA hybrid structure (40). Figure 4B shows that same preference in the melting assay. Ethidium shifts the Tm of poly(rA)·poly(dT), but does not appreciably alter the melting temperatures of any other polynucleotides in the mixture at the molar ratio added. Competition dialysis experiments (Figure 5B) validate the structural preference observed in the melting assay.

With the melting assay validated by netropsin and ethidium, an unknown compound was studied to illustrate the utility of the method. A derivative of the natural product β lapachone (45) clearly shows a strong preference for the DNA:RNA hybrid poly(dA)·poly(rU) (Figure 4C). That is a wholly novel type of nucleic acid structural recognition that is under detailed biophysical study in our laboratory. The tantalizing result is shown here only to illustrate the utility of method. A more complete biophysical study of this unusual binding interaction has been completed and will be reported elsewhere.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

New types of thermal denaturation assays were described for the study of sequence- and structural-selective nucleic acid binding. Mixtures of polynucleotides or oligonucleotides of different sequences or structures with well-resolved melting temperatures can be prepared and subjected to thermal denaturation. Addition of ligands at low molar ratios results in elevation of the Tm of the polynucleotide with the most preferred sequence or structure. The advantages of the assay are many. The assay is simple, direct, inexpensive and rapid. As a spectrophotometric assay, the method is amenable to automation and multiplexing. Proof of principle of the method was provided here with simple mixtures that are nonetheless complicated enough to be interesting. The composition of the mixtures can be designed in accord with the particular interests of the investigator and with regard to the nucleic acid being targeted. Simple 3 to 5 component mixtures were described here, but there is no reason to prevent the design of more complex mixtures to provide more stringent tests of selectivity.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant CA35635 from the National Cancer Institute. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the James Graham Brown Foundation and the grant listed above.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hurley L.H. Secondary DNA structures as molecular targets for cancer therapeutics. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2001;29:692–696. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley L.H. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:188–200. doi: 10.1038/nrc749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mergny J.L., Helene C. G-quadraplex DNA: a target for drug design. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:1366–1367. doi: 10.1038/3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neidle S., Thurston D.E. Chemical approaches to the discovery and development of cancer therapies. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrc1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darnell J.E., Jr Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:740–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dervan P.B. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:2215–2235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dervan P.B., Baker B.F. Design of sequence-specific DNA cleaving molecules. Comparison of distamycin-EDTA X Fe(II) and N-bromoacetyldistamycin. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1986;471:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb48025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dervan P.B., Doss R.M., Marques M.A. Programmable DNA binding oligomers for control of transcription. Curr. Med. Chem. Anti-Canc Agents. 2005;5:373–387. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dervan P.B., Edelson B.S. Recognition of the DNA minor groove by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:284–299. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janowski B.A., Kaihatsu K., Huffman K.E., Schwartz J.C., Ram R., Hardy D., Mendelson C.R., Corey D.R. Inhibiting transcription of chromosomal DNA with antigene peptide nucleic acids. Nature Chem. Biol. 2005;1:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nchembio724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu X., Trent J.O., Fokt I., Priebe W., Chaires J.B. From the cover: allosteric, chiral-selective drug binding to DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12032–12037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200221397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurley L.H., Wheelhouse R.T., Sun D., Kerwin S.M., Salazar M., Fedoroff O.Y., Han F.X., Han H., Izbicka E., Von Hoff D.D. G-quadruplexes as targets for drug design. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;85:141–158. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neidle S., Parkinson G. Telomere maintenance as a target for anticancer drug discovery. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:383–393. doi: 10.1038/nrd793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grand C.L., Han H., Munoz R.M., Weitman S., Von Hoff D.D., Hurley L.H., Bearss D.J. The cationic porphyrin TMPyP4 down-regulates c-MYC and human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:565–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim M.Y., Gleason-Guzman M., Izbicka E., Nishioka D., Hurley L.H. The different biological effects of telomestatin and TMPyP4 can be attributed to their selectivity for interaction with intramolecular or intermolecular G-quadruplex structures. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3247–3256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seenisamy J., Bashyam S., Gokhale V., Vankayalapati H., Sun D., Siddiqui-Jain A., Streiner N., Shin-Ya K., White E., Wilson W.D., et al. Design and synthesis of an expanded porphyrin that has selectivity for the c-MYC G-quadruplex structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2944–2959. doi: 10.1021/ja0444482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seenisamy J., Rezler E.M., Powell T.J., Tye D., Gokhale V., Joshi C.S., Siddiqui-Jain A., Hurley L.H. The dynamic character of the G-quadruplex element in the c-MYC promoter and modification by TMPyP4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8702–8709. doi: 10.1021/ja040022b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui-Jain A., Grand C.L., Bearss D.J., Hurley L.H. Direct evidence for a G-quadruplex in a promoter region and its targeting with a small molecule to repress c-MYC transcription. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11593–11598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182256799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane M.J., Dabrowiak J.C., Vournakis J.N. Sequence specificity of actinomycin D and Netropsin binding to pBR322 DNA analyzed by protection from DNase I. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:3260–3264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low C.M., Drew H.R., Waring M.J. Sequence-specific binding of echinomycin to DNA: evidence for conformational changes affecting flanking sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4865–4879. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.12.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Dyke M.W., Hertzberg R.P., Dervan P.B. Map of distamycin, netropsin, and actinomycin binding sites on heterogeneous DNA: DNA cleavage-inhibition patterns with methidiumpropyl-EDTA.Fe(II) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:5470–5474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.18.5470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaires J.B. Application of Equilibrium Binding Methods to Elucidate the Sequence Specificity of Antibiotic Binding to DNA. In: Hurley L.H., editor. Advances in DNA Sequence Specific Agents. Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc.; 1992. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller W., Crothers D.M. Interactions of heteroaromatic compounds with nucleic acids. 1. The influence of heteroatoms and polarizability on the base specificity of intercalating ligands. Eur. J. Biochem. 1975;54:267–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb04137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaires J.B. A Competition Dialysis Assay for the Study of Structure-Selective Ligand Binding to Nucleic Acids. In: Beaucage S.L., Bergstrom D.E., Glick G.D., Jones R.A., editors. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Vol. 1. NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. pp. 8.3.1–8.3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren J., Chaires J.B. Sequence and structural selectivity of nucleic acid binding ligands. Biochem. 1999;38:16067–16075. doi: 10.1021/bi992070s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren J., Chaires J.B. Rapid screening of structurally selective ligand binding to nucleic acids. Methods Enzymol. 2001;340:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)40419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaires J.B. Competition dialysis: an assay to measure the structural selectivity of drug-nucleic acid interactions. Curr. Med. Chem. Anti-Canc Agents. 2005;5:339–352. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazurkin Y.S., Frank-Kamenetskii M.D., Trifonov E.N. Melting of DNA: its study and application as a research method. Biopolymers. 1970;9:1253–1306. doi: 10.1002/bip.1970.360091102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crothers D.M. Statistical thermodynamics of nucleic acid melting transitions with coupled binding equilibria. Biopolymers. 1971;10:2147–2160. doi: 10.1002/bip.360101110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGhee J.D. Theoretical calculations of the helix-coil transition of DNA in the presence of large, cooperatively binding ligands. Biopolymers. 1976;15:1345–1375. doi: 10.1002/bip.1976.360150710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson W.D., Tanious F.A., Fernandez-Saiz M., Rigl C.T. Evaluation of drug-nucleic acid interactions by thermal melting curves. Methods Mol. Biol. 1997;90:219–240. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-447-X:219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leng F., Priebe W., Chaires J.B. Ultratight DNA binding of a new bisintercalating anthracycline antibiotic. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1743–1753. doi: 10.1021/bi9720742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darby R.A., Sollogoub M., McKeen C., Brown L., Risitano A., Brown N., Barton C., Brown T., Fox K.R. High throughput measurement of duplex, triplex and quadruplex melting curves using molecular beacons and a LightCycler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e39. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox K.R., Waring M.J. Footprinting at low temperatures: evidence that ethidium and other simple intercalators can discriminate between different nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:491–507. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai L., Chen L., Raghavan S., Ratliff R., Moyzis R., Rich A. Intercalated cytosine motif and novel adenine clusters in the crystal structure of the Tetrahymena telomere. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4696–4705. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.20.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaires J.B. Biophysical chemistry of the daunomycin-DNA interaction. Biophys Chem. 1990;35:191–202. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(90)80008-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaires J.B., Fox K.R., Herrera J.E., Britt M., Waring M.J. Site and sequence specificity of the daunomycin–DNA interaction. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8227–8236. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox K.R., Waring M.J. DNA structural variations produced by actinomycin and distamycin as revealed by DNAase I footprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:9271–9285. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.24.9271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francis R., West C., Friedman S.H. Targeting telomerase via its key RNA/DNA heteroduplex. Bioorganic Chem. 2001;29:107–117. doi: 10.1006/bioo.2000.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren J., Qu X., Dattagupta N., Chaires J.B. Molecular recognition of a RNA:DNA hybrid structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6742–6743. doi: 10.1021/ja015649y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West C., Francis R., Friedman S.H. Small molecule/nucleic acid affinity chromatography: application for the identification of telomerase inhibitors which target its key RNA/DNA heteroduplex. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:2727–2730. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fritzsche H., Rupprecht A. Modulation of the B-A transition of DNA by potential antitumor antibiotics. Influence of the base composition of DNA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1990;7:1135–1140. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1990.10508551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmer C., Marck C., Guschlbauer W. Z-DNA and other non-B-DNA structures are reversed to B-DNA by interaction with netropsin. FEBS Lett. 1983;154:156–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailly C., Colson P., Houssier C., Hamy F. The binding mode of drugs to the TAR RNA of HIV-1 studied by electric linear dichroism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1460–1464. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Moura K.C., Salomao K., Menna-Barreto R.F., Emery F.S., Pinto Mdo C., Pinto A.V., de Castro S.L. Studies on the trypanocidal activity of semi-synthetic pyran[b-4,3]naphtho[1,2-d]imidazoles from beta-lapachone. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2004;39:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plum G.E. Optical Methods. In: Beaucage S.L., Bergstrom D.E., Glick G.D., Jones R.A., editors. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000. pp. 7.3.1–7.3.17. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.