Abstract

Objective: To evaluate evidence of the effectiveness of computer-generated health behavior interventions—clinical encounters “in absentia”—as extensions of face-to-face patient care in an ambulatory setting.

Data Sources: Systematic electronic database and manual searches of multiple sources (1996–1999) plus search for gray literature were conducted to identify clinical trials using computer-generated health behavior interventions to motivate individuals to adopt treatment regimens, focusing on patient-interactive interventions and use of health behavior models.

Study Selection: Eligibility criteria included randomized controlled studies with some evidence of instrument reliability and validity; use of at least one patient-interactive targeted or tailored feedback, reminder, or educational intervention intended to influence or improve a stated health behavior; and an association between one intervention variable and a health behavior.

Data Extraction: Studies were described by delivery device (print, automated telephone, computer, and mobile communication) and intervention type (personalized, targeted, and tailored). We employed qualitative methods to analyze the retrieval set and explore the issue of patientinteractive computer-generated behavioral intervention systems.

Data Synthesis: Studies varied widely in methodology, quality, subject number, and characteristics, measurement of effects and health behavior focus. Of 37 eligible trials, 34 (91.9 percent) reported either statistically significant or improved outcomes. Fourteen studies used targeted interventions; 23 used tailored. Of the 14 targeted intervention studies, 13 (92.9 percent) reported improved outcomes. Of the 23 tailored intervention studies, 21 (91.3 percent) reported improved outcomes.

Conclusions: The literature indicates that computer-generated health behavior interventions are effective. While there is evidence that tailored interventions can more positively affect health behavior change than can targeted, personalized or generic interventions, there is little research comparing different tailoring protocols with one another. Only those studies using print and telephone devices reported a theoretic basis for their methodology. Future studies need to identify which models are best suited to which health behavior, whether certain delivery devices are more appropriate for different health behaviors, and how ambulatory care can benefit from patients' use of portable devices.

The number of controlled trials, reviews, and reports in the literature and popular media suggests that interest in using technology to augment patient– physician interactions has increased in the last decade. Recently, a JAMIA article recommended that telemedical services and information systems address behavior change, individual risk factors, and patient education, and further predicted that “the trend is toward delivery of care in an ambulatory setting or by interaction with a patient directly at home, and telemedicine services and information systems provide the necessary communication links.”1

The purpose of this study is to report the current state of the peer-reviewed evidence for patient-interactive computer-generated health behavior interventions—clinical encounters “in absentia”—as extensions of face-to-face patient care. We were interested in two specific areas: the health behavior models used in these interventions and the devices used for patient education, counseling, and reminder systems aimed at improving patient health behaviors.

Background

Other Reviews

Other reviews have focused on a specific delivery method (e.g., telephone-delivered interventions) or a particular health behavior focus (e.g., smoking cessation). To our knowledge, this is the first review to summarize findings across all interventions that involve devices that communicate or interact directly with the patient, regardless of technology, health behaviors, or medical conditions. Intervention types are also defined more narrowly and more consistently than in previous literature reviews (as discussed under Methods). While other reviews describe the growing role of telecommunication in health care, this review specifically examines the state of computer-generated or computer-operated therapeutic communications. Table 1▶ summarizes previous review papers.

Table 1.

▪ Summary of Reviews and Analyses of Personalized, Targeted, and Tailored Interventions

| Author | Intervention Focus | Method | Delivery Device |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skinner et al., 199371 | Patient education | Overview, 31 articles and reviews | Computer-assisted instruction, telephone |

| Alemi and Stephens, 199672 | Preventive care, ambulatory setting; patient education | Overview, 4 projects | Telephone, print materials |

| Shea et al., 199673 | Preventive care, ambulatory setting | Meta-analysis, 16 trials | Computer-generated reminders |

| Balas et al., 199723 | Distance medicine technology | Literature review, 61 trials | Computer systems, telephone |

| Piette, 199774 | Diabetes management | Literature review, 33 studies | Telephone using AVM (automated voice messaging) |

| Balas et al.,199875 | Diabetes management | Literature review, 15 studies | Computer systems, print materials |

| Marcus et al.,199876 | Physical exercise | Literature review, 28 studies | Mass media-based interventions |

| Wagner, 199877 | Mammography screening | Meta-analysis, 16 articles | Print materials |

| Bental et al., 199919 | Patient information systems | Overview, 15 projects | Computer systems, print materials |

| Brug et al., 199918 | Nutrition | Overview, 8 studies | Print materials |

| Kristal et al., 199978 | Nutrition | Review, 10 studies | Print materials |

| McBride and Rimer, 199979 | Telephone-delivery | Literature review, 74 trials | Telephone |

| Strecher, 199922 | Smoking cessation | Literature review, 10 studies | Print materials |

Theoretic Models

Patients are increasingly involved in managing their health care,2 and health care providers are challenged to motivate, educate, and help people adhere to healthy behaviors and medication regimens in the ambulatory setting.3 Understanding why people behave the way they do and identifying the factors underlying behavioral change help in the development and evaluation of effective health behavior interventions.4 Although a review of theories is outside the scope of this paper, we mention the four cognitive-behavioral models used most frequently in the studies reviewed.

Cognitive-behavioral theories focus on the individual level and use two key concepts—behavior (as mediated through cognitions) and knowledge (which is necessary but not sufficient to produce behavior change). These theories focus on intrapersonal factors such as an individual's knowledge, beliefs, motivation, attitudes, developmental history, experience, skills, self-concept, and behavior. Models using an intrapersonal approach are the stages of change, or transtheoretic, model (TM), the health belief model (HBM), and the theory of reasoned action/theory of planned behavior (TRA).5,6 The TM is concerned with an individual's readiness to change.6,7 The HBM focuses on an individual's perception of the threat of a health problem.4 The TRA focuses on an individual's intention to perform a behavior.6 Social-cognitive theory incorporates intrapersonal and interpersonal factors; as in the HBM and TRA, the benefits of a behavior must outweigh the costs; also, a person must have a sense of self-efficacy or personal agency about the behavior.8,9 Personal empowerment, an individual's ability to cope with situations and perceived sense of control over them, is emphasized.8,10 Table 2▶ summarizes the concepts of each theory.

Table 2.

▪ Models and Concepts for Health Behavior Change

| Concept | Definition | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Health Belief Model: | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | One's opinion of chances of getting a condition | Personalize risk based on a person's features or behavior. |

| Perceived severity | One's opinion of how serious a condition and its consequences are | Specify consequences of the risk and the condition. |

| Perceived benefits | One's opinion of the efficacy of the advised action to reduce risk or seriousness of impact | Define action to take; how, where, when; clarify the positive effects to be expected. |

| Perceived barriers | One's opinion of the tangible and psycho- logical costs of the action | Identify and reduce barriers through reassurance, incentives, assistance. |

| Cues to action | Strategies to activate “readiness” | Provide how-to information, promote awareness, provide reminders. |

| Self-efficacy | Confidence in one's ability to take action | Provide training, guidance in performing action. |

| Stages-of-Change Model: | ||

| Pre-contemplation | Unaware of problem, hasn't thought about changes | Increase awareness of need for change, personalize information on risks and benefits. |

| Contemplation | Thinking about change, in the near future. | Motivate, encourage to make specific plans. |

| Preparation | Making a plan to change | Assist in developing concrete action plans, setting gradual goals. |

| Action | Implementation of specific action plans | Assist with feedback, problem solving, social support, reinforcement. |

| Maintenance | Continuation of desirable actions, or repeating periodic recommended step(s) | Assist in coping, reminders, finding alternatives, avoiding slips/relapses (as applicable). |

| Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action: | ||

| Behavioral intention | Perceived likelihood of performing the behavior; prerequisite for action | Define action; identify how much effort one is planning to exert to reach goal. |

| Attitude | One's favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior | Identify outcomes of action. |

| Behavioral belief | Belief that behavioral performance is asso- ciated with certain attributes or outcomes | Provide information about outcomes; clarify positive effects to be expected. |

| Normative belief | Subjective belief regarding approval or disapproval of the behavior | Identify barriers and advantages of behavior. |

| Subjective norm | Influence of perceived social pressure; weighted by one's motivation to comply with perceived expectations | Identify specific groups or individuals of influence; identify how much their approval or disapproval affects action. |

| Perceived behavioral control (Theory of Reasoned Action only) | One's perception of how easy or difficult it will be to act | Incorporate information about likely results of action in advice. |

| Social Cognitive Theory: | ||

| Reciprocal determinism | Behavior changes result from interaction between individual and environment | Work to change environment. |

| Behavioral capability | Knowledge and skills to influence behavior | Provide information and training about action. |

| Expectations | Beliefs about likely results of action | Incorporate information about likely results of action into advice. |

| Self-efficacy | Confidence in ability to take action and persist in action | Point out strengths; use persuasion and encouragement; approach behavior change in small steps. |

| Observational learning | Beliefs based on observing others | Point out others' experience; identify role models. |

| Reinforcement | Responses to a person's behavior that increase or decrease chances of recurrence | Provide incentives, rewards, praise; encourage self-reward. |

Sources: Bandura,8 Glanz et al.,4 Prochaska et al.,7,41 Rhodes et al.,5 and Skinner and Kreuter.6

An appropriate theoretic framework applied to development of health behavior messages can greatly enhance a patient's motivation to comply with an intervention.5 Further enhancement can be achieved using patient characteristics in conjunction with computer production capabilities to approximate a face-to-face clinical encounter.6

Another enhancement feature may be achieved by using mobile devices rather than delivery methods that tether ambulatory patients to a computer, telephone, or mailbox. Mobile devices such as cell phones or pagers are particularly suitable for outpatient interventions, since patients can carry them easily. These devices have received considerable popular media and commercial attention,11–13 so we made an effort to find papers that described their use. The price of mobile communication devices has dropped dramatically in the last decade, so the increasing power and decreasing cost of communication may provide opportunities for therapeutic interventions that were not feasible before. In addition, their portability and convenience seem to create an attachment or synergy between the user and the device, which can bond the user to the intervention protocol.14

Methods

The literature that describes this area of investigation is not indexed in a single database. We therefore designed a search strategy that involved searching across multiple databases using both free text and appropriate specialized terminology.

Data Sources

Databases searched included medline (1966–99), HealthSTAR (1981–99), cinahl (1982–99), Current Contents (1997–99), embase (1990-1999), inspec (1969–1999), PsycINFO (1967–1999), and Sociological Abstracts (1986–1999). We also searched the Cochrane Collaboration and Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Index) databases. To account for gray literature, we searched CRISP (Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects) and Dissertation Abstracts, contacted authors, and conducted targeted Internet searches. We also searched lexis-nexis for more popular literature on this subject.

Searches were limited to publications in English. A summary of key terms and phrases is given in Table 3▶.

Table 3.

▪ Key Words Used in Literature Review

| Key Words | Additional Terms |

|---|---|

| Compliance | Adherence |

| Motivation | |

| Patient education | Education |

| Decision making | |

| Empowerment | |

| Preventive health services | Self-help |

| Health behavior | |

| Ambulatory care | |

| Reminder systems | Drug monitoring |

| Intervention | |

| Patient reminder | |

| Tailored reminder | |

| Targeted reminder | |

| Tailored intervention | |

| Targeted intervention | |

| Computer | Computer communication networks |

| Computer systems | |

| Telephone | Telephone systems |

| Pager | Paging technology |

| Print communication | Letter |

| Postcard | |

| Communication | Counseling |

| Self-assessment |

Study Selection

Eligibility for inclusion in the final set included:

Controlled clinical trials and quasi-experimental studies with some evidence of instrument reliability and validity

At least one patient-interactive feedback, reminder, or educational intervention intended to influence or improve a stated health behavior

An association between one intervention variable and a health behavior

Eligible trials were evaluated using the rating system described in Table 4▶. Ratings were based on recommendations from the literature.15,16 Articles received a score from 1 to 10; sampling and randomization aspects and presence of a control group were weighted most heavily (totaling 7 points). The minimum score was set at 5 for inclusion.

Table 4.

▪ Rating System

| Factor | Description | Possible Points |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Assignment to different interventions by chance | 2 |

| Control group | Comparison made to group of subjects not given the health behavior intervention | 2 |

| Theory or model used | Theoretic basis for intervention design | 1 |

| Rationale for using chosen model and rejecting other options | ||

| Sampling | Sampling method described | 3 |

| Sample composition clearly described | ||

| Sample of adequate size | ||

| Number and ratio of withdrawals described | ||

| Analysis of main effect variables | Clear definition for each variable | 1 |

| Clear description of methods and results | ||

| Numeric table presented for each effect variable | ||

| Content | Intervention clearly described and replicable | 1 |

| Discussion of withdrawals | ||

| Discussion of study limitations |

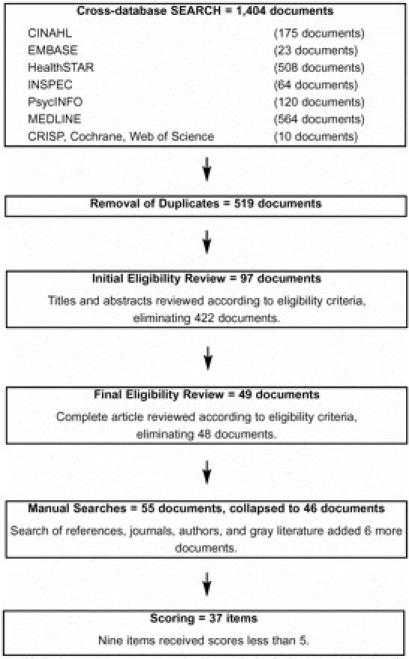

The initial cross-database search yielded 1,404 publications; this was reduced to 519 after elimination of duplicates. Review of the title and abstract of each publication yielded 97 publications potentially meeting eligibility criteria. After review of these articles, 49 publications were eliminated because they did not meet the eligibility criteria (the primary cause was a focus on physician reminders). Manual searches of the bibliographies of remaining articles, reviews, key journals in the appropriate fields, and key individuals yielded another 6 articles, for a total of 55; multiple reports of studies were collapsed to yield a final total of 46 studies in this review. Nine of these are feasibility or quasi-experimental studies included because they describe promising approaches. Figure 1▶ illustrates our selection process.

Figure 1.

Search and selection process.

Data Extraction and Definitions

Each item was scored using the rating system described in Table 1▶. Items were classified by intervention type, delivery device, and use of synchronous vs. asynchronous interaction.

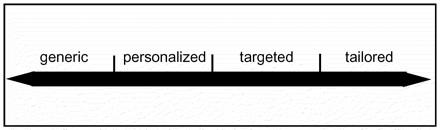

We defined three intervention types according to features accepted in the literature: personalized, targeted, and tailored. Personalized messages have the person's name on the information he or she receives. The message content is not adapted to the individual's diagnostic, behavioral or motivational characteristics.17 Personalized intervention studies were eliminated unless a higher level intervention (i.e., targeted or tailored, or both) was also a condition in the study.

Targeted message content is customized to reach a specific subgroup of the general population, based on the principles of market segmentation. Content is customized to “target” broad psychographic (i.e., activities, interests, and opinions) and sociodemographic groups. Targeted interventions do not account for personal differences in intervention needs among individuals in the target population, but they may be personalized.18

Tailored interventions are messages or a series of messages based on a specific individual's characteristics, as determined through historical records, replies to questions, or replies to previous messages. Tailored messages are generally based on published theoretic models, and message content is specific to one individual at one point in time. One of the goals of a tailored intervention is for patients to perceive the information as applying only to them.17,19,20 An example of a tailored intervention is delivering messages or information contingent on a patient's “stage of change,” a model postulating that patients will respond to and better remember messages presented on cue. For instance, patients who have just quit smoking will respond better to messages pitched to the “action” phase than the “precontemplative” phase.21,22 The actual messages are picked from a large pool of potential responses either manually by a therapist or through a largely automated process designed by a therapist.

The primary distinction between targeted and tailored interventions is that tailoring adapts content or the way content is presented according to the needs of the individual. Material is not fixed and feedback is based on individual, not subgroup, characteristics. Devices used for feedback range from the most simplistic, such as tailored letters, to expert systems incorporating behavior change models into an interactive messaging system.

Interventions can be distinguished along a continuum, from generic (or “one-size-fits-all”) to highly individualized, tailored approaches as seen in Figure 2▶. Confusion between targeted and tailored interventions is compounded by researchers' inconsistent use of the terminology.22

Figure 2.

Intervention types continuum.

We grouped intervention delivery devices into categories adapted from Balas et al.23: 1) mobile communication systems (use of a pager, mobile telephone, or other wireless system for delivery), 2) computerized communication systems (use of a computer, modem, touch-sensitive screen, or other interfacing equipment for delivery), 3) automated telephone communication (usually computer-generated messages using a regular telephone line and telephone), and 4) print communication (use of a letter, bulletin, fax transmission, newsletter, postcard, or manual delivery).

We also distinguished between synchronous and asynchronous communication. Synchronous communication is like communication by telephone—dialog occurs in real time. Asynchronous communication is like e-mail—two parties carry on a dialog by leaving messages, but do not usually communicate in real time.

Results

Of the 46 studies meeting our inclusion criteria, 9 received scores below 5. These studies were excluded from analysis but are included in Table 5▶ because they illustrate promising approaches and merit discussion.

Table 5.

▪ Summary of Targeted and Tailored Interventions, Categorized by Delivery Device

| Author[s] | Methods | Health Behavior | N | Results | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Communications: | |||||

| Facchinetti & Korman, 1996,62199863 | Quasi-experimental controlled trial | Medication adherence: reduce drug holidays | 24 | Text pager improved adherence, reduced number of “drug holidays” and total number of days without therapy. | 4 |

| Reminder system vs. control | |||||

| Targeted, asynchronous | |||||

| (PRN: Prescription Reminder Network) | |||||

| Milch et al.,199664 | Quasi-experimental | Medication adherence: increase compliance | 6 | Mean compliance rose from 56% to 96% during pager use. | 1 |

| Medication use before (control period) and during pager use | |||||

| Targeted, asynchronous | |||||

| (Neuropage) | |||||

| Dunbar et al., 200065 | Quasi-experimental | Medication adherence: increase compliance | 26 | Patients on HIV medications reported high acceptance of paging system. | 2 |

| Interactive reminder system | |||||

| Targeted, synchronous | |||||

| (CareWave) | |||||

| Computer Systems: | |||||

| Shultz et al.,199257 | RCT: Transmission of glucometer results via modem once a week vs. standard diary results | Diabetes: reduce blood glucose levels | 20 | Significant improvement in reduced blood glucose levels in modem intervention group over traditional diary group. | 6 |

| Targeted, synchronous | |||||

| Turnin, 199258 | RCT: Diabeto use (computer-aided instruction) vs. no Diabeto use | Diabetes: increase dietetic knowledge and improved diabetes self-care | 105 | Diabeto use associated with significant improvement in dietetic knowledge, some decrease in caloric excess in overeaters, decrease in fat intake in over-consumers, increase in carbohydrate intake in under- consumers; no impact on caloric deficit. | 9 |

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| (Diabeto) | |||||

| Buchanan et al., 1993,59 199560 | Quasi-experimental | Migraine: improve understanding of migraines | 16 | Presentation of information based on individual patient's medical record, concerns, questions, and physician input. | 1 |

| Interactive explanation system | System “accepted by patients.” | ||||

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| (Migraine) | |||||

| Carenini et al., 199461 | Quasi-experimental | Migraine: improve understanding of migraines | 16 | Presentation of information based on individual patient's medical record, concerns, questions, and physician input. | 1 |

| Interactive explanation system | Patients “found system useful.” | ||||

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| (Migraneur) | |||||

| Gustafson et al., 1994,55 199956 | RCT: CHESS use vs. no CHESS use | Information and support: improve social support, mood, and quality of life | 204 | CHESS users reported improved cognitive functioning, sense of social support, and more active life; reported more participation in health care and decreased levels of negative emotions. | 9 |

| Tailored, synchronous | No significant differences between groups for depression, physical functioning or reported level of energy. | ||||

| (CHESS: Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System) | |||||

| Binsted et al., 199580 | Quasi-experimental | Diabetes: improve diabetes self-care | 10 | Generation of diabetes information collected through medical record; includes personalized reminders. | 1 |

| Interactive explanation system | Patients and medical staff found system helpful and easy to use. | ||||

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| (PIGLET: Personalized Intelligent Generator of Little Explanatory Texts) | |||||

| McRoy et al., 199883 | Quasi-experimental | Medical history taking: increase understanding of medical conditions and treatment | 35 | User satisfaction measured via online questionnaire: 87% of users completed evaluations; 87% prefer online system to paper. | 1 |

| Generation of customized educational materials and medical explanations | Other findings: users like having medical information tailored to their interests; 71% found definitions somewhat or very helpful; 58% found dialog sections helpful. | ||||

| User satisfaction questionnaires completed online | |||||

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| (LEAF: Layman Education and Activation Form) | |||||

| Jones et al., 1996,81 199982 | RCT: Personalized cancer information (P) vs. general cancer information output via “computer consultation” (G) vs. cancer booklet (B) information group | Information and support: increase understanding of cancer information | 525 | P reported higher satisfaction with information, thought information was relevant, and learned something new. | 9 |

| Tailored, synchronous | B more likely to feel overwhelmed by information than P or G. P and G thought information was limited. | ||||

| Printed information use at home: 83% B; 57% G; 70% P. | |||||

| P and G groups also sent printouts of information viewed; P more likely to use this information than G. | |||||

| Rolnick et al., 199954 | RCT: CHESS use vs. no CHESS use (included receiving a book related to either HIV or breast cancer) | Information and support: improve social support, mood and quality of life | 107 | HIV group: discussion service used more often (time and number of uses). | 9 |

| Targeted, synchronous | Breast cancer group: discussions were “disease-based.” | ||||

| (CHESS) | |||||

| Automated Telephone Communications: | |||||

| Ahring et al., 199251 | RCT: Transmission of glucometer results via telephone once a week vs. standard diary results every 6 weeks | Diabetes: reduced blood glucose levels | 42 | Significant difference in blood glucose levels between 6-week and 12-week experimental groups. | 6 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | Approximately two thirds of experimental group expressed increased understanding of blood-glucose control, motivation for self-management and general knowledge about diabetes. | ||||

| Stehr-Green 199349 | RCT: Computer-generated telephoned immunization reminders vs. control | Preventive health: increase immunization rate | 222 | 11.6% improvement in immunization rates in intervention group. On-time immunizations: 52.9% intervention, 41.3% control. | 9 |

| Targeted, asynchronous. | |||||

| Friedman et al., 1996,44 199745 | RCT: TLC use vs. no TLC use (control) | Hypertension: increase medication compliance and lower blood pressure | 267 | Medication adherence: improved 17.7%–18% in TLC, 11.7%–12% in control. If nonadherent at baseline: 36% improvement TLC, 26% control. | 10 |

| Tailored, synchronous | Blood pressure: mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased in both groups. | ||||

| (TLC: Telephone-linked Care) | |||||

| Model: social cognitive theory | |||||

| Hyman et al., 199650 | RCT: Computer-interactive phone call re: total cholesterol and weight vs. no call (control) | Preventive health: decrease cholesterol level and body weight | 115 | Subjects recruited from those who completed a 4-week cholesterol behavioral and diet program. | 9 |

| Targeted, synchronous | No significant difference between experimentals and controls. | ||||

| Baer and Geist, 199784 | Quasi-experimental | Mental health: increase adherence to behavior therapy program | 65 | Patients who completed two or more phone sessions were “greatly improved.” | 2 |

| Computer-administered behavior therapy program (BT STEPS) using interactive voice response (IVR) | |||||

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| Model: “behavioral theory” | |||||

| Jarvis et al., 199747 | RCT: TLC vs. control | Physical exercise: increase activity | 52 | Increase in stage of change: TLC 88%, control 62%. | 7 |

| Tailored, synchronous | |||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Piette and Mah, 199753 | Feasibility study | Diabetes: improve diabetic self-care | 65 | 98% reported no difficulty under-standing and responding to AVM queries. AVM system could identify potentially serious health problems. 71% were willing to listen to preventive care messages. | 2 |

| Automated voice message (AVM) calls vs. no calls | |||||

| Targeted, synchronous | |||||

| Friedman, 199846 | RCT: Report of three TLC studies: hypertension medication adherence (MA); dietary modification (DietAid); exercise (ACT) | Hypertension: increase medication adherence and lower blood pressure | 267 | MA: 18% mean adherence improvement in TLC users vs. 12% control. TLC diastolic blood pressure reduction 5.2 mm Hg vs. 0.8 mm Hg in control. | 10 |

| TLC use vs. no TLC use (control) | Physical exercise: increase activity | DietAid: TLC reduced mean total cholesterol vs. no change in control. | |||

| Tailored, synchronous | ACT: TLC increased walking to 121 min/week vs. 40 min/week in control. | ||||

| Models: social cognitive theory, stages of change | |||||

| Lieu et al., 199848 | Randomized trial: Automated telephone call (TC) vs. letter only (L) vs. TC followed by L (TC+L) vs. L followed by TC (L+TC) | Preventive heath: increase immunization rate | 648 | TC+L and L+TC led to significantly higher immunization rates than L or TC. | 8 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: health belief | |||||

| Meneghini et al., 199852 | Controlled trial | Diabetes: lower diabetes or hypoglycemic crises and emergency room visits | 107 | 58% of clinic patients used ECM. | 5 |

| Daily report of self-measured glucose levels or hypoglycemic symptoms via voice-interactive phone system vs. no ECM use | Three-fold decrease of diabetes-related crises or hypoglycemia in ECM group. Two-fold decrease in clinic visits of complex diabetes management issues. | ||||

| Targeted, synchronous | |||||

| (ECM: Electronic Case Manager) | |||||

| Print Communications: | |||||

| Prochaska et al., 199341 | Randomized assignment via stage of change | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 756 | ITT outperformed other conditions at each f/u point and demonstrated higher prolonged abstinence rates than other groups. | 8 |

| Standardized self-help manual (ALA+) vs. manual matched to stage (TTT) vs. interactive computer report plus individualized manual (ITT) vs. four counselor calls plus stage manual plus report (PITT) | |||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Campbell et al., 199426 | RCT: Well-child appointment letter vs. postcard vs. control | Preventive health: increase immunization rate | 558 | Letter and postcard rates significantly higher than control rates (75.0%, 73.7%, and 67.5%, respectively). | 10 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | No difference between letter and postcard groups. | ||||

| Model: health belief model | |||||

| Campbell et al., 199431 | RCT: Multicenter study. | Nutrition: lower fat intake | 558 | Tailored group was more than twice aslikely as non-tailored group to remember receiving information. | 10 |

| Tailored nutrition information packet vs. non-tailored packet vs. control | Tailored group significantly reduced total fat and saturated fat intakes compared with control. | ||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Models: health belief model; stages of change | |||||

| Osman et al., 199489 | RCT: Computer-generated tailored asthma education booklet (BI) vs. standard oral education (control) | Asthma: decrease hospital admissions | 801 | BI associated with reduction in hospital admissions for patients judged most vulnerable on study entry. | 9 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Rimer and Orleans, 199486 | Controlled trial | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 901 | GC used Clear Horizons Guide tailored to older adult population. | 8 |

| Tailored guide and counselor calls (GC) vs. standard guide (G) vs. control (CO) | 20% of GC reported not smoking 12 months after intervention vs. 12% of G. | ||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | Higher proportion of both GC and G used quitting techniques, were more likely to set a quit date and use nicotine reductiontechniques than controls. | ||||

| Skinner et al., 199429 | RCT: Individualized mammogram recommendation letters vs. standard letter | Preventive health: increase mammogram rate | 435 | Individualized letter recipients were more highly associated with mammogram follow-up if income<$26,000 or if African-American. | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | Overall, individualized letters were better remembered and more thoroughly read than standard letters | ||||

| Model: stages of change | Higher-educated women less likely to report interest in content. | ||||

| Strecher et al., 199443 | RCT: Tailored letter vs. generic letter vs. control | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 51 &197 | Younger smokers more likely to quit | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | Significant effects of tailored letters only for moderate to light smokers. | ||||

| Models: health belief, stages of change | |||||

| Brug et al, 1996,32 1998,33 1999a,34 1999b35 | RCT: Tailored vs. non-tailored1996 and 1999b: Tailored vs. general nutrition information | Nutrition: lower fat intake, increase fruit and vegetable intake | 1996, 1999b: 347 | 1996: Significant short-term effect of tailored messages on fat intake and opinions about vegetable and fruit intake. No significant effect on fruit and vegetable intake. | 10 |

| 1998: Tailored letter and iterative feedback (TI) vs. tailored letter (TL) vs. general letter (CO) | 1998: 762 | 1998: TI and TL lower mean fat scores than CO. TI and TL higher mean vege- table scores than CO. No significant differences between TI and TL groups. | |||

| 1999a: Tailored feedback vs. tailored feedback and psychosocial information letter | 1999a: 315 | 1999a: Significant reduction in mean fat score. Mean fruit intake increase. No vegetable change. | |||

| Tailored, asynchronous | 1999b: Personalized dietary and psycho- social feedback more likely to be read, seen as personally relevant and motivating to reduce fat intake. | ||||

| Models: social cognitive theory, theory of planned behavior | |||||

| Kreuter and Strecher, 199688 | RCT: Enhanced health risk assessment (HRA) vs. standard HRA vs. control | Preventive health: decrease fat intake and cholesterol and increase activity | 1,317 | Each behavior analyzed separately. | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | Enhanced HRA led to statistically or nearly statistically significant effects for cholesterol test, fat reduction, and exercise. | ||||

| Models: health belief, stages of change | |||||

| Campbell et al., 199767 | RCT: Risk result feedback vs. control | Preventive health: increase Pap test rate | 411 | No statistical difference between groups. | 9 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | Women 50 to 70 years old who received results were “more likely” to have a Pap test in the next 6 months. | ||||

| Baker et al., 199825 | RCT: Personalized targeted reminder letter from physician vs. personalized postcard from physician vs. generic postcard vs. control | Preventive health: increase influenza immunization rate | 24,743 | 64% of targeted letter group remembered reminders vs. 39% combined postcard groups. | 9 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | Targeted letter more effective than either postcard intervention. | ||||

| Dijkstra et al., 199839,42 | RCT: Information on outcomes of quitting (O); self-efficacy-enhancing information (SE); O + SE; or no information (CO) | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 752 | Subjects considering change benefited most from O + SE intervention; those planning to quit benefited most from SE intervention. | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | Significantly more smokers in O, SE, and O + SE interventions attempted 24-hour quits. | ||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Dijkstra et al., 199838 | RCT: 3 tailored letters and self-help guide (3TS) vs. 3 tailored letters only (3T) vs. 1 tailored letter and self-help guide (TS) vs. 1 tailored letter only (T) vs. non-tailored intervention (CO) | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 752 | 3TS and 3T: more stage transition; higher intention to quit than CO; higher impact than TS or T. | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | TS led to more quitting behavior than CO. | ||||

| Model: stages of change | No difference between T and CO. | ||||

| In heavy smokers, tailored messages did not lead to more quitting than TS, T, or CO. | |||||

| Greene and Rossi, 199836 | RCT: 1 dietary feedback report and educational materials vs. control. Fat intake and stage-of-change assessments at 0, 6, 12, and 18 months | Nutrition: lower fat intake | 296 | Rate of progression to action stage by 18 months was found in 9%–12% of subjects in precontemplation or contemplation stage; 24% preparation stage subjects; 40% unclassified subjects. | 10 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Marcus et al., 199885 | RCT: Individual motivationally-tailored reports (IT) VS. standard self-help booklets (ST) | Physical exercise: increase activity | 194 | IT: significant increase in physical activity each week and self-reported time exercising; more likely to reach action stage of motivational readiness for physical activity adoption. | 10 |

| Targeted, asynchronous | |||||

| Models: stages of change, health belief | |||||

| Bastani et al., 199927 | Randomized 2-group design | Preventive health: increase mammogram screening | 901 | 8% increase in mammography after intervention. | 10 |

| Educational booklet and personalized health risk letter | No intervention effect in women under 50 years of age. | ||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Bull et al., 199968 | Clinical controlled trial | Physical exercise: increase activity | 763 | No significant differences between groups. | 10 |

| Tailored pamphlet vs. standard pamphlet vs. control | |||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Campbell et al., 199987 | RCT: Multi-level, multi-component intervention | Nutrition: lower fat intake, increase fruit and vegetable intake | 459 | Recall receiving bulletin: 72.9% SPIR, 64.6% EXP, 38.2% control. | 10 |

| Bulletin-orientations: expert (EXP) vs. spiritual and pastor-oriented (SPIR) vs. standard | High trustworthiness: 63.5% SPIR, 53.6% EXP, 48.6% control. | ||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | High credibility: 45% SPIR, 31% EXP, 33% control. | ||||

| Model: stages of change | Fruit/vegetable intake: SPIR did not differ significantly from EXP. SPIR and EXP mean consumption significantly higher than control. | ||||

| High impact of pamphlets: 58% SPIR, 45% EXP. | |||||

| Dijkstra et al., 199940 | RCT: Multiple tailored (MT) vs. single tailored (ST) letters vs. standard self- help guide (SHG) vs. control (CO) | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 843 | MT had more effect than SHG or ST. | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | ST had more effect than CO. | ||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Lutz et al., 199937 | RCT: Tailored newsletter with tailored goal-setting component (TG) vs. tailored newsletter without goal-setting component (T) vs. non-tailored newsletter (NT) vs. control (CO) | Nutrition: increase fruit and vegetable intake compared with control | 710 | Daily fruit and vegetable intake was higher for all 3 newsletter groups | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | Differences from baseline to post-intervention were greatest in TG; next was T, then NT. | ||||

| Models: social cognitive theory, stages of change | No statistically significant differences among tailored newsletter groups. | ||||

| Myers et al., 199930 | RCT: Minimal intervention (MI) vs. enhanced intervention (EI) | Preventive health: increase prostate cancer screening rate | 413 | Age of 50 years or older positively associated with adherence. Married men more likely to adhere. Belief in having an early detection exam in the absence of symptoms predicted adherence. | 10 |

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: preventive health, a combination of health belief model, theory of reasoned action, and social cognitive theory | |||||

| Raats et al., 199966 | Clinical trial. | Nutrition: lower fat intake | 171 | No real difference between groups. | 8 |

| Tailored feedback vs. no feedback | |||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: theory of planned behavior | |||||

| Rimer et al., 199928 | Randomized trial | Preventive health: increase Pap and mammogram screening rates | 1,318 | TPC+TTC did not perform better than PI. | 8 |

| Provider prompting alone (PI) vs. provider prompting and tailored print materials (TPC) vs. provider prompting and tailored print materials and tailored phone counseling (TPC+TTC) | TPC+TTC: 35%–40% increase for Pap tests and overall cancer screening. | ||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | Subgroup findings: TPC+TTC most effective on Pap among women who worked for pay and those who viewed interventions as “meant for them.” TPC+TTC most effective for mammo- graphy among married women. | ||||

| Model: stages of change | |||||

| Velicer and Prochaska, 199990 | Report of 4 studies | Smoking cessation: abstinence from smoking tobacco | 756 to 4,144 | Cessation rates: 22%–26% | 8 |

| Computer-generated (Pathways to Change expert system intervention) tailored report | |||||

| Tailored, asynchronous | |||||

| Model: stages of change |

Notes: RCT indicates randomized controlled clinical trial.

Lack of homogeneity among the remaining 37 studies precluded pooling of data; our findings, therefore, form a descriptive literature review. Studies varied by recruitment method, subject characteristics, study design, time frame, setting, measurement of effects, and health behavior focus. Many studies reported multiple outcomes; several used targeted or tailored interventions in conjunction with personalized or generic interventions; some used more than one targeted or tailored intervention.

Of 37 studies, 33 (89.2 percent) reported improved outcomes and 20 of these (60.6 percent) were statistically significant. Fourteen studies used targeted interventions; 23 used tailoring. Eleven of the targeted intervention studies (78.6 percent) reported improved outcomes; 6 of these (54.5 percent) were statistically significant. Of the 23 tailored intervention studies, 22 (95.7 percent) reported improved outcomes; 15 of these (68.2 percent) were statistically significant. Table 5▶ lists the studies by delivery device.

No Intervention Benefits

Four studies50,66–68 did not report statistically significant or improved outcomes. Lack of effect was explained by use of a limited, non-intensive one-time feedback with no inclusion of psychosocial factors66 and use of similar messages for both control and intervention protocols.68

Use of Models

Only 23 studies (62.2 percent) stated use of a theory to guide the health behavior intervention: 19 were print communications, 4 were telephone.

Comment on Emerging Technologies

Clinicians' use of pagers, personal digital assistants, PalmPilots, and laptop computers as portable information resource devices is a subject of numerous studies.69 Just as clinicians have found that these devices provide a greater sense of control, mastery, and personal empowerment in the work setting, perhaps patients may also find such devices advantageous when managing their treatment regimens in the outpatient setting. Portability of “always ready” devices in combination with the messaging interventions can create a synergistic feedback loop between patient and device as evidenced by Milch's finding64 that “several of the patients allowed that the pager became a trusted friend” and Dunbar's report65 of high patient engagement with a pager system.

Mobile systems may have clear advantages over computer, telephone, or print communication systems for delivery of tailored health behavior interventions, because they offer the benefits of constancy—”anytime, anywhere” messaging and communication capability14; physical freedom—because the system is wireless and mobile, the patient is not restricted to one physical environment to receive messages14; privacy—messages can be modified so that others cannot observe or interact with them14; and temporal flexibility—users can interact with the content when available or postpone interaction if desired.24

Yet a portable system is not without limitations and disadvantages. Potential problems include acceptance—studies reporting general acceptance of computerized and mobile delivery systems have had small numbers of subjects, so we do not know whether a selection bias or novelty variable is involved in this outcome; intrusiveness—the “anytime, anywhere” feature may be too intrusive for long-term use; and economic consequences—we do not know how a portable system may economically affect a patient, a practitioner, or the health care system. Only 13 studies in this review* considered cost as a factor of a system's feasibility or success.

Conclusion

Our review indicates that many studies demonstrate the effectiveness of “clinical encounters in absentia,” but few good studies incorporate leading edge communication technologies. The studies reviewed here represent the best available evidence to date of the effectiveness of targeted and tailored health behavior interventions across health behaviors.

An overwhelming majority (91.3 percent) of tailored intervention studies reported improved outcomes, as did 92.9 percent of those studies that used targeting; however, little research compared tailored to targeted interventions. We therefore cannot conclude that tailoring is more effective than targeting. One notable exception is Prochaska et al.41 Using the stages of change model to characterize readiness to quit smoking, they compared two tailored interventions to a targeted condition and general smoking cessation materials. At the 18-month follow-up period, tailored interventions outperformed both targeted and generic conditions and were associated with higher prolonged abstinence rates than other conditions. This study offers evidence that tailored interventions can more positively influence health behavior change than targeted, personalized, or generic interventions, but more studies like this need to be conducted.

There has also been little research comparing different tailoring protocols to one another. One group of smoking cessation studies compared three types of tailored interventions matched to stage of change to controls,39,42 four types of tailored interventions to a nontailored intervention,38 and two types of tailored interventions to generic material and controls.36 Two patterns emerged: there was more forward stage transition in the tailored groups compared with controls, and multiple interventions were more effective than single tailored interventions. Studies of this kind must be conducted for health behaviors other than smoking.

It is notable that only those studies using print and telephone devices reported a theoretical basis for their methodology. Future studies need to identify which models are best suited to which health behaviors and whether certain delivery devices are more appropriate for different health behaviors. While “it is not inconceivable to view computer technology for health promotion and the delivery of services as a form of medical intervention with patient satisfaction, compliance, and improved health status as the goals,”3 we need to know to what extent such interventions can beneficially replace interpersonal health behavior recommendations. In addition, usability studies could elucidate the complex process of human interaction with technology—the interplay between interface design and human cognition. The current research shows that isolated paper, telephone, and computer-delivered communications can cause health-enhancing behavior change. The communication of these behavior change models over an integrated Internet linked array of delivery devices, pagers, cell phones, interactive television, and computers with portable devices is technically feasible today.

Friedman et al.45 have stated that “in the future there will be devices in general use that will incorporate features of the current telephone, television, video, and computer as well as wireless devices that people will be able to carry with them.” That future is currently possible through the use of tetherless devices such as pagers and personal digital assistants, but research on these devices currently lags far behind research on print, telephone, and computerized communications.

In 1997, Balas et al.70 predicted that, “in the future, application of distance technology may strengthen the continuity of care between patient and clinician by improving access and supporting the coordination of health care activities from a single source.”23 Technology has finally reached the point that health behavior models can be integrated with computer-generated interventions to provide consistent, continuous interactive ambulatory care. What is missing is comprehensive measurement of the effectiveness of these systems, which has the potential to not only inform the organization and delivery of health care but help move the science of medical informatics toward the goal of achieving the status of a “mature science.”

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sherrilynne S. Fuller, PhD, and Rona L. Levy, PhD, for helpful comments in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Greenes RA, Lorenzi NM. Audacious goals for health and biomedical informatics in the new millennium. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5:395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake C. Consumers are using the Internet to revolutionize health care. AORN J. 1999;70:1068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold WR. Facilitating the adoption of new technology for health promotion in health care organizations. In: Street RL, Gold WR, Manning T (eds). Health Promotion and Interactive Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997:209–20.

- 4.Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK (eds). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass, 1997.

- 5.Rhodes F, Fishbein M, Reis J. Using behavioral theory in computer-based health promotion and appraisal. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner CS, Kreuter MW. Using theories in planning interactive computer programs. In: Street RL, Gold WR, Manning T (eds). Health Promotion and Interactive Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997:39–66.

- 7.Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK (eds). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass, 1997:60–84.

- 8.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1997;84:191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranowski T, Perry CL, Parcel GS. How individuals, environments, and health behavior interact: social cognitive theory. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK (eds). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass, 1997:153–78.

- 10.Ozer EM, Bandura A. Mechanisms governing empowerment effects: a self-efficacy analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:472–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noble S. PDAs and hand-helds: world without wires. Health Manage Technol. 2000:28. [PubMed]

- 12.RXVP adopts Sun Microsystems technology to provide health services. System News for Sun Users. Commercial Data Systems Web site. 1999. Available at: [http://system-news.cdsinc.com/system-news/jobdir/submitted/2000.05/2241/2241.html. Accessed Nov 28, 2000.

- 13.Gorman J. The size of things to come. NY Times. Sunday, Jun 11, 2000; pp 21–2.

- 14.Mann S. Wearable computing as a means for personal empowerment. Proc 1st Int Conf Wearable Comput (ICWC ‘98). Los Alamitos, Calif: IEEE Computer Society Press, 1998.

- 15.Balas EA, Austin SM, Brown GD, Mitchell JA. Quality evaluation of controlled clinical information service trials. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1993: 586–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Moher D, Hadad AR, Tugwell P. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: current issues and future directions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1996;12:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries H, Brug J. Computer-tailored interventions motivating people to adopt health promoting behaviours: introduction to a new approach. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brug J, Campbell M, van Assema P. The application and impact of computer-generated personalized nutrition education: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bental DS, Cawsey A, Jones R. Patient information systems that tailor to the individual. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dijkstra A, De Vries H. The development of computer-generated tailored interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Vries H, Mudde AN, Dijkstra A, Willemsen MC. Differential beliefs, perceived social influences, and self-efficacy expectations among smokers in various motivational phases. Prev Med. 1998;27:681–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strecher VJ. Computer-tailored smoking cessation materials: a review and discussion. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36: 107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balas EA, Jaffrey F, Kuperman GJ, et al. Electronic communication with patients: evaluation of distance medicine technology. JAMA. 1997;278:152–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimal RN, Flora JA. Interactive technology attributes in health promotion: practical and theoretical issues. In: Street RL, Gold WR, Manning T (eds). Health Promotion and Interactive Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997:19–38.

- 25.Baker AM, McCarthy B, Gurley VF, Yood MU. Influenza immunization in a managed care organization. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:469–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell JR, Szilagyi PG, Rodewald LE, Doane C, Roghmann KJ. Patient-specific reminder letters and pediatric well-child-care show rates. Clin Pediatr. 1994;33:268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bastani R, Maxwell AE, Bradford C, Das IP, Yan KX. Tailored risk notification for women with a family history of breast cancer. Prev Med. 1999;29:355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimer BK, Conaway M, Lyna P, et al. The impact of tailored interventions on a community health center population. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37:125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skinner CS, Strecher VJ, Hospers H. Physicians' recommendations for mammography: do tailored messages make a difference? Am J Public Health. 1994;84:43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers RE, Chodak GW, Wolf TA, et al. Adherence by African American men to prostate cancer education and early detection. Cancer. 1999;86:88–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell MK, DeVellis BM, Strecher VJ, Ammerman AS, DeVellis RF, Sandler RS. Improving dietary behavior: the effectiveness of tailored messages in primary care settings. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:783–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brug J, Steenhuis I, Van Assema P, de Vries H, Glanz K. The impact of a computer-tailored nutrition intervention. Prev Med. 1996;25:236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brug J, Glanz K, Van Assema P, Kok G, van Breukelen GJP. The impact of computer-tailored feedback and iterative feedback on fat, fruit, and vegetable intake. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:517–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brug J, Steenhuis I, van Assema P, Glanz K, De Vries H. Computer-tailored nutrition education: differences between two interventions. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brug J. Dutch research into the development and impact of computer-tailored nutrition education. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999;53(suppl 2):S78–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greene GW, Rossi SR. Stages of change for reducing dietary fat intake over 18 months. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lutz SF, Ammerman AS, Atwood JR, Campbell MK, DeVellis RF, Rosamond WD. Innovative newsletter interventions improve fruit and vegetable consumption in healthy adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;6:705–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J, van Breukelen G. Tailoring information to enhance quitting in smokers with low motivation to quit: three basic efficacy questions. Health Psychol. 1998;17:513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J. Long-term effectiveness of computer-generated tailored feedback in smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 1998;13:207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J. Targeting smokers with low readiness to change with tailored and nontailored self-help materials. Prev Med. 1999;28:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Velicer WF, Rossi JS. Standardized, individualized, interactive, and personalized self-help programs for smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1993;12:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J, van Breukelen G. Tailored interventions to communicate stage-matched information to smokers in different motivational stages. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998a;66:549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strecher VJ, Kreuter M, Den Boer DJ, Kobrin S, Hospers HJ, Skinner CS. The effects of computer-tailored smoking cessation messages in family practice settings. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:262–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedman RH, Kazis LE, Jette A, et al. A telecommunications system for monitoring and counseling patients with hypertension: impact on medication adherence and blood pressure control. Am J Hypertension. 1996;9(4 pt 1):285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedman RH, Stollerman JE, Mahoney DM, Rozenblum L. The virtual visit: using telecommunications technology to take care of patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:413–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman RH. Automated telephone conversations to assess health behavior and deliver behavioral interventions. J Med Syst. 1998;22:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jarvis KL, Friedman RH, Heeren T, Cullinane PM. Older women and physical activity: using the telephone to walk. Womens Health Issues. 1997;7:24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lieu TA, Capra AM, Makol J, Black SB, Shinefield HR. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of letters, automated telephone messages, or both for underimmunized children in a health maintenance organization. Pediatrics. 1998;101: E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stehr-Green PA, Dini EF, Lindegren ML, Patriarca PA. Evaluation of telephoned computer-generated reminders to improve immunization coverage at inner-city clinics. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:426–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hyman DJ, Herd JA, Ho KSI, Dunn JK, Gregory KA. Maintenance of cholesterol reduction using automated telephone calls. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:129–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahring KK, Ahring JP, Joyce C, Farid NR. Telephone modem access improves diabetes control in those with insulin-requiring diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:971–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meneghini LF, Albisser AM, Goldberg RB, Mintz DH. An electronic case manager for diabetes control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piette JD, Mah CA. The feasibility of automated voice messaging as an adjunct to diabetes outpatient care. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rolnick SJ, Owens B, Botta R, et al. Computerized information and support for patients with breast cancer or HIV infection. Nurs Outlook. 1999;47:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, Bricker E, Pingree S, Chan CL. The use and impact of a computer-based support system for people living with AIDS and HIV infection. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994:604–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, et al. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/ support system. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shultz EK, Bauman A, Hayward M, Holzman R. Improved care of patients with diabetes through telecommunications. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;670:141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turnin MC, Beddok RH, Clottes J, et al. Telematic expert system Diabeto: new tool for diet self-monitoring for diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buchanan BG, Moore J, Forsythe D, Banks G, Ohlsson S. Involving patients in health care: explanation in the clinical setting. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1993:510–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Buchanan BG, Moore JD, Forsythe DE, Carenini G, Ohlsson S, Banks G. An intelligent interactive system for delivering individualized information to patients. Artif Intell Med. 1995;7:117–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carenini G, Mittal VO, Moore JD. Generating patient-specific interactive natural language explanations. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994:5–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Facchinetti NJ, Korman LB. Text pagers used to remind patients: a pilot study [prepublication report]. Storrs, Conn: University of Connecticut, School of Pharmacy, 1996.

- 63.Facchinetti NJ, Korman LB. Using paging technology for reminding patients. HMO Pract. 1998;12:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Milch RA, Ziv L, Evans V, Hillebrand M. The effect of an alphanumeric paging system on patient compliance with medicinal regimens. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1996;13:46–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dunbar PJ, Madigan D, Woodward J, Groshof L, Minstrel J, Hooton TM. Feasibility of a two-way messaging system in HIV-infected patients on HAART. [prepublication report]. Seattle, Wash: University of Washington, 2000.

- 66.Raats MM, Sparks P, Geekie MA, Shepherd R. The effects of providing personalized dietary feedback: a semicomputerized approach. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37: 177–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campbell E, Peterkin D, Abbott R, Rogers J. Encouraging underscreened women to have cervical cancer screening: the effectiveness of a computer strategy. Prev Med. 1997;26:801–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bull FC, Jamrozik K, Blanksby BA. Tailored advice on exercise-does it make a difference? Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:230–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilcox A, Hripcsak G, Knirsch CA. Using palmtop computers to retrieve clinical information. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:1017.

- 70.Friedman CP. Toward a measured approach to medical informatics. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 1999;6:176–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Skinner CS, Siegfried JC, Kegler MC, Strecher VJ. The potential of computers in patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 1993;22:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alemi F, Stephens RC. Computer services for patients: description of systems and summary of findings. Med Care. 1996;34(10 suppl):OS1–OS9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shea S, CuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piette JD. Moving diabetes management from clinic to community: development of a prototype based on automated voice messaging. Diabetes Educ. 1997a;23:672–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Balas EA, Boren SA, Griffing G. Computerized management of diabetes: a synthesis of controlled trials. Proc AMIA Annu Symp. 1998:295–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Marcus BH, Owen N, Forsyth LH, Cavill NA, Fridinger F. Physical activity interventions using mass media, print media, and information technology. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:362–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wagner TH. The effectiveness of mailed patient reminders on mammography screening: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kristal AR, Glanz K, Curry SJ, Patterson RE. How can stages of change be best used in dietary interventions? J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:679–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McBride CM, Rimer BK. Using the telephone to improve health behavior and health service delivery. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37:3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Binsted K, Cawsey A, Jones R. Generating personalised patient information using the medical record. Proc 5th Conf Artif Intell Med (AIME ‘95). 1995:29–41.

- 81.Jones R, Pearson J, Cawsey A, Barrett A. Information for patients with cancer. Does personalization make a difference? Pilot study results and randomised trial in progress. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996;423–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Jones R, Pearson J, McGregor S, et al. Randomized trial of personalized computer based information for cancer patients. BMJ. 1999;319:1241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McRoy SW, Liu-Perez A, Ali SS. Interactive computerized health care education. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5:347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baer L, Greist JH. An interactive computer-administered self-assessment and self-help program for behavior therapy. J Clin Psychiat. 1997;58 (suppl 12):23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marcus BH, Brock BC, Pinto BM, Forsyth LAH, Roberts MB, Traficante RM. Efficacy of an individualized, motivationally-tailored physical activity intervention. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rimer BK, Orleans CT. Tailoring smoking cessation for older adults. Cancer. 1994;74(7 suppl):2051–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Campbell MK, Bernhardt JM, Waldmiller M, et al. Varying the message source in computer-tailored nutrition education. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:157–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ. Do tailored behavior change messages enhance the effectiveness of health risk appraisal? Results from a randomized trial. Health Educ Res. 1996;11:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Osman LN, Abdalla MI, Beattie JAG, et al. Reducing hospital admission through computer supported education for asthma patients. BMJ. 1994;308:568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. An expert system intervention for smoking cessation. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]