Abstract

Oncogenic Ha-Ras is a potent inhibitor of skeletal muscle cell differentiation, yet the Ras effector mediating this process remains unidentified. Here we demonstrate that the atypical protein kinases (aPKCs; λ and/or ζ) are downstream Ras effectors responsible for Ras-dependent inhibition of myogenic differentiation in a satellite cell line. First, ectopic expression of Ha-RasG12V induces translocation of PKCλ from the cytosol to the nucleus, suggesting that aPKCs are activated by Ras in myoblasts. The aPKCs function as downstream Ras effectors since inhibition of aPKCs by expression of a dominant negative PKCζ mutant or by treatment of cells with an inhibitor, GO6983, promotes myogenesis in skeletal muscle satellite cells expressing oncogenic Ha-Ras. Arresting cell proliferation synergistically enhances myogenic differentiation only when aPKCs are also inhibited. Thus, the repression of myogenic differentiation in a satellite cell line appears to be directly mediated by aPKCs acting as Ras effectors and indirectly mediated via stimulation of cell proliferation.

The Ras family of GTPases are important intracellular switches for signal transduction pathways that control cellular proliferation, transformation, and differentiation. Multiple Ras effectors, including Raf, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K), and RalGDS, contribute to the ability of oncogenic H-Ras to affect cellular physiology (3). Oncogenic Ha-Ras is a strong promoter of cell proliferation and has long been known to repress skeletal myogenesis (17, 25), presumably by mimicking signaling events generated by growth factor action on myoblasts.

The downstream effector of activated Ha-Ras that inhibits skeletal muscle differentiation is not known and is unlikely to rely on activation of either Raf, PI3-K, or RalGDS either indirectly or in combination. This suggests that a novel, Ha-Ras-activated signaling pathway is critical for inhibition of myogenic differentiation (22, 26, 27). Atypical protein kinases (aPKCs) have been reported to play critical roles in Ha-Ras signal transduction (2, 8, 33), and to interact directly with Ha-Ras (7). PKCs are a large family of structurally related serine/threonine protein kinases that are catoregized into three major subgroups; the classical or conventional PKC isotypes (cPKCs) are Ca2+ and diacylglycerol (DAG) dependent, the novel PKCs (nPKCs) are Ca2+ independent but DAG responsive, and the aPKC isozymes (λ/ι and ζ) require neither Ca2+ nor DAG for activation. In contrast to cPKCs or nPKCs, aPKC isoforms also do not respond to phorbol ester treatment (23, 24, 31).

In this study, we demonstrated that the aPKCs are necessary effectors of Ha-Ras that repress myogenic differentiation in a satellite cell line. Using a reporter gene whose expression relies on muscle cell differentiation and myoblast fusion assays, we showed that either dominant negative mutants of aPKCs or an aPKC-specific pharmaceutical inhibitor, GO6983, can induce differentiation of Ha-RasG12V-expressing MM14 myoblasts. Inhibition of cell proliferation either by blocking the Raf/MKK1,2/ERK1,2 signaling pathway or by reducing serum synergistically enhances myogenesis only when aPKCs are inhibited. These data demonstrate that aPKCs are likely to function as direct Ras effectors in a Ras-dependent pathway that represses myogenic differentiation, which cooperates with Ras-dependent and Ras-independent pathways that indirectly repress myogenesis via stimulation of cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Mouse MM14 cells were cultured as described previously (18). Growth conditions included different levels of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) and 15% horse serum. Differentiation conditions lacked FGF-2 but include 15% horse serum. Cells transfected with activated Ras mutants were grown under differentiation conditions unless otherwise noted.

DNA transfection.

Expression vectors encoding a constitutively active mutant of human Ha-Ras, Ha-RasG12V, and its derivatives (Ha-RasG12C40, Ha-RasG12S35, and Ha-RasG12G37), as well as wild-type and dominant negative mutants of PKCζ and PKCλ, are described elsewhere (1, 6, 16, 34).

DNA was transiently transfected into MM14 cells by a calcium phosphate-DNA precipitation method as described previously (18). A pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) was used as an empty control expression vector. Equivalent DNA concentrations were maintained by the addition of a pBS SK(+) plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.)

Reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR analysis of aPKCs.

Total RNA was isolated from Ha-RasG12V-transfected cells 48 h after transfection, when the transfectants represent 50 to 75% of the total cell population. Reverse transcription and PCR were carried out as described previously (19). Each PCR amplification was performed for 40 cycles (1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C) using primers FGFR1 (positive control) (AGAGACCAGCTGTGATGA [forward] and GGCCACTTTGGTCACACG [reverse]) (19), atypical PKCζ (CGCGAATTGTCAACGGACATCCTGATTACCAGCG [forward] and CGCGAATTGTCAACCGGTTGTTCTGGGATGCTTG [reverse]) (15), and atypical PKCλ (CGCGAATTGTCAACAGTGAGGAGATGCCGACCCAGAGG [forward] and CGCGAATTGTCAACCTGAAAGCCTCTTCTAACTCCAAC [reverse]) (15). After the amplification, each reaction product was resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized with a UV transilluminator.

Immunohistochemistry.

Cells were transfected as described below, plated on coverslips (treated as previously described [11]), grown for 36 h in growth medium containing FGF-2, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Primary antibodies, which recognize PKCζ (1:500) or PKCλ (1:500) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), were used to detect the expression of the corresponding proteins. A rabbit polyclonal anti-β-galactosidase antibody (1:250; Sigma) was used to identify transfected cells. Primary antibodies were detected using fluorophor-conjugated secondary Alexa 488 (1:500) or Alexa 549 (1:500) donkey anti-goat or goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Molecular Probes). Nuclei were visualized by 4",6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Alexa-conjugated antibody stains were detected using a Nikon E800 or Zeiss Axioplan2 fluorescence microscope equiped for digital confocal microscopy by Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, Co.

Clonal growth assay.

MM14 cells were grown on six-well plates to a density of 5 × 104 cells/well and transfected with the indicated expression vectors or control plasmids along with a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-LacZ expression plasmid encoding β-galactosidase. Cells were trypsinized (0.05% trypsin, 0.53 mM EDTA) and replated at clonal density (1,000 cells per 10-cm plate) 1 h after transfection. The cells were maintained in the presence (0.3 nM) or absence of FGF-2, cultured for 36 h, and then processed for β-galactosidase histochemistry as described elsewhere (29). The number of cells in β-galactosidase-positive clones was determined.

Muscle-specific promoter assay.

A differentiation-sensitive muscle-specific reporter activity assay was used to determine the extent of MM14 differentiation following transient transfection. The reporter contained the firefly luciferase gene driven by a muscle-specific promoter (human α-cardiac actin promoter) (18). MM14 cells were assayed for relative luciferase activity as described previously (9).

Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activity assay.

ERK1,2 kinase activity was determined using the Pathdetect ELK1 reporting system (Stratagene) (35). For this assay, MM14 cells were plated on six-well plates at a density of 104 cells/well and cotransfected with 2.5 μg of pFR-Luc reporter vector, 200 ng of pFA-Elk1 vector, and 1 μg of CMV-LacZ vector per well. The cells were harvested and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities as described previously (9).

Myotube formation assay.

MM14 cells were plated at 105 cells/well in six-well plates and transfected as described for the clonal growth assay. The cells were harvested for assay 48 h after transfection and processed for β-galactosidase histochemistry as described elsewhere (29). A minimum of 600 nuclei in β-galactosidase-positive cells were scored per plate, and the percentage of nuclei in multinucleated cells (two or more nuclei) was determined.

RESULTS

Ha-Ras is a well-known inhibitor of myogenic differentiation, yet the signaling mechanisms used are unknown. We used a mouse myoblast cell line (MM14) to model the responses of primary skeletal muscle satellite cells (4). Previously, we have demonstrated that constitutively active Ha-Ras stimulates the proliferation and inhibits the differentiation of MM14 myoblasts (10). As reported here, we have identified a downstream component of an Ha-Ras signal transduction pathway that acts to negatively regulate the differentiation of skeletal muscle cells.

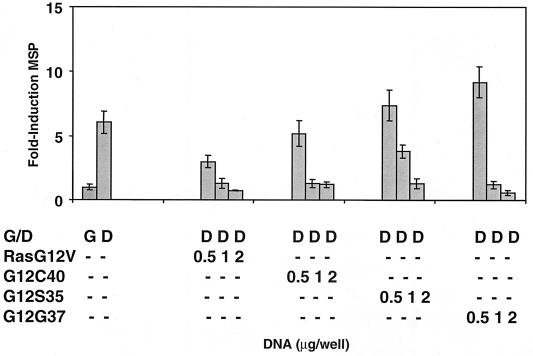

Oncogenic Ha-Ras mutants (Ha-RasG12S35, Ha-RasG12G37, and Ha-RasG12C40) that are defective in activation of downstream Ha-Ras effectors such as RalGDS and PI3-K, Raf and PI3-K, or Raf and RalGDS, respectively, are fully capable of inhibiting muscle gene expression in the absence of FGF (Fig. 1). The capacity for Ha-Ras and the Ras effector domain mutants to inhibit muscle gene expression is dose dependent (Fig. 1), and control transfections with an empty vector (pcDNA3) have no detectable effect (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Raf, RalGDS, and PI3-K signaling are not involved in oncogenic Ha-Ras-mediated repression of muscle gene expression. MM14 cells were cotransfected with the MSP reporter, a CMV-LacZ expression vector, and a plasmid encoding either Ha-RasG12V, Ha-RasG12S35, Ha-RasG12C40, or Ha-RasG12G37 at the concentrations indicated. G and D specify growth and differentiation culture conditions as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were harvested and the normalized luciferase activities were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are the means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated three times with comparable results.

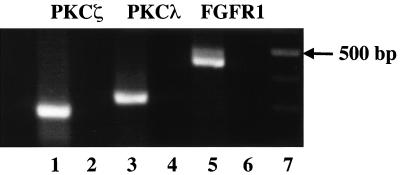

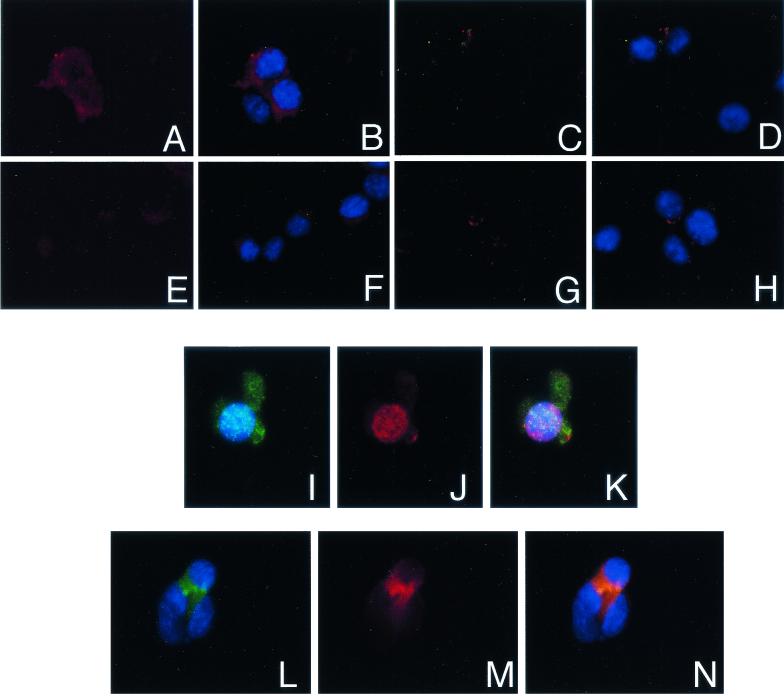

The ability of the Ha-Ras effector domain mutants to effectively repress myogenesis was unexpected. Since it has recently been reported that the physiological action of Ha-Ras in some cell types is dependent on the activity of the aPKC isoforms (2, 8, 15, 33) and that the aPKCs may be effectors of Ras since they bind activated Ras directly (7), we asked if aPKCs were expressed in MM14 cells. Ha-RasG12V-transfected MM14 cells express both ζ and λ aPKC isoforms as shown by RT-PCR (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical analyses show that PKCλ is localized to the cytoplasm in control transfected cells (Fig. 3 A and B)while PKCζ staining is barely detectable (Fig. 3E and F) compared to that of control cells lacking primary antibody for PKCλ (Fig. 3C and D) or PKCζ (Fig. 3G and H). Western blot analysis of proliferating MM14 cells showed a single band for aPKC, whereas PKCζ was undetectable (data not shown). We then asked if both PKCλ and PKCζ were readily detectable by immunohistochemistry in MM14 cells expressing the activated Ha-RasG12V mutant. We noted that PKCλ in Ha-RasG12V-expressing cells (Fig. 3I) often appeared to be localized to the nucleus (Fig. 3J and K), in contrast to the cytoplasmic localization in control transfected cells (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, PKCζ was localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 3M and N) in Ha-RasG12V-expressing cells (Fig. 3L).

FIG. 2.

Ha-RasG12V-transfected MM14 myoblasts express both PKCζ and PKCλ. The results of an RT-PCR analysis of aPKC steady-state mRNA levels in MM14 cells are shown. RT-PCR of total RNA from Ha-RasG12V-transfected MM14 cells demonstrates that cells express both PKCζ (lane 1) and PKCλ (lane 2). RT-PCR for FGFR1 was used as a positive control (lane 3). The predicted sizes for PKCζ, PKCλ, and FGFR-1 are 255, 305, and 450 bp, respectively. Lanes 2, 4, and 6 lack reverse transcriptase, and lane 7 contains a 100-bp DNA ladder.

FIG. 3.

Transfection with the RasG12V mutant induces aPKC expression in MM14 myoblasts. MM14 cells were transfected with a control pBS SK(+) vector (A to H) or an expression vector encoding RasG12V (I to N) and a β-galactosidase expression vector (A to N). The cells were analyzed for expression of aPKCs 36 h posttransfection by immunohistochemistry. aPKC-expressing cells appear red for PKCλ (A, B, J, and K) and PKCζ (E F, M, and N). Nuclei (blue) are stained with DAPI (B, D, F, H, I, K, L, and N), and all three colors are shown in panels K and N. RasG12V-transfected cells expressing β-galactosidase appear green (I, K, L, and N). Primary antibodies were omitted to show background staining (C, D, G, and H).

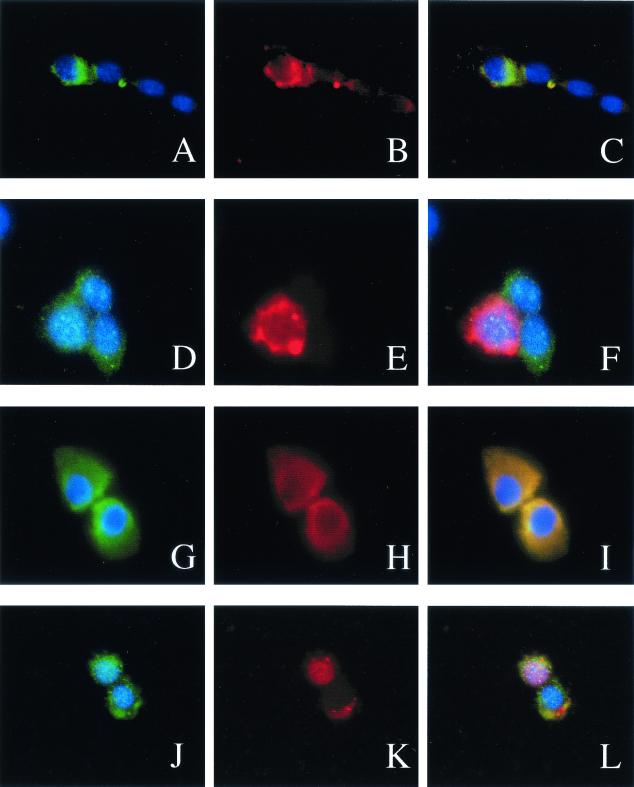

Changes in the subcellular localization of PKC isoforms are indicative of their activation. Typically, inactive PKC isozymes are thought to be present mainly in the cytosol, and on activation PKCs are found to be associated with different subcellular components (27). To further analyze the subcellular distribution of aPKCs in MM14 myoblasts, we examined the localization of ectopically expressed PKCζ or PKCλ in the absence or presence of the activated Ha-RasG12V mutant (Fig. 4). While PKCζ remained in the cytosol in both the absence and presence of ectopically expressed Ha-RasG12V (Fig. 4A to F), in over 200 cells scored we observed a 2.5-fold increase in the nuclear localization of PKCλ in Ha-RasG12V-expressing cells (Fig. 4G to L). Since the known Ras effector mutants are fully capable of repressing myogenic differentiation and since Ha-RasG12V promotes translocation of aPKCs in MM14 cells, we asked if aPCKs were involved in transducing the Ras signals that inhibit myogenesis.

FIG. 4.

Transfection with the RasG12V mutant induces a change in the intracellular PKCλ localization in MM14 myoblasts. MM14 cells were transfected with pBS SK(+) (A to F) or an expression vector encoding RasG12V (G to L) and expression vectors encoding wtPKCζ (A to C and G to I) or wtPKCλ (D to F and J to L) and β-galactosidase (all cells). Cells were transfected, processed, and analyzed by immunohistochemical staining as described for Fig. 3. Transfected, β-galactosidase-positive cells appear green, and cells expressing aPKCs appear red. All three colors are shown in panels C, F, I, and L.

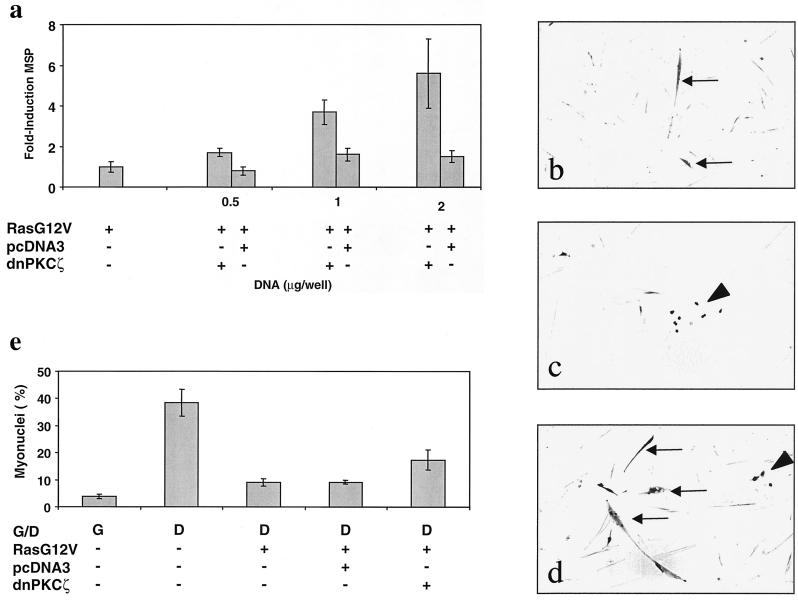

To determine whether aPKCs mediate Ras effects in skeletal muscle cells, MM14 cells were cotransfected with Ha-RasG12V and a dominant negative mutant of PKCζ or PKCλ and maintained under differentiation conditions. In cells overexpressing Ha-RasG12V, ectopic expression of dominant negative PKCζ, which may operate in a heterologous fashion (12), induced muscle gene expression (Fig. 5a). Moreover, the induction of muscle gene expression by mutant PKCζ is dose dependent (Fig. 5a). Consistent with this observation, cotransfection of MM14 cells with expression vectors encoding Ha-RasG12V, the mutant PKCζ, and β-galactosidase (to identify transfected cells) inhibited the ability of oncogenic Ha-Ras to repress myogenesis and thus significantly increased myotube formation (Fig. 5c and d) compared to control transfected cells (Fig. 5b). A quantitative analysis revealed a twofold increase in myotube formation when dominant negative PKCζ was expressed (Fig. 5e). This was, however, significantly less fusion than that observed when mock-transfected cells were maintained under differentiation conditions. Transfection with a dominant negative mutant of PKCλ had a similar effect on myotube formation when MM14 cells overexpressed Ha-RasG12V (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Transfection with dominant negative PKCζ reverses oncogenic Ha-Ras-dependent repression of myogenesis. (a) MM14 cells were cotransfected with the MSP reporter, a CMV-LacZ expression vector, an Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) plasmid, and either a dominant negative PKCζ-encoding plasmid or a control (pcDNA3) as indicated. The cells were assayed as described for Fig. 1, and the data shown are the means and standard deviation of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. (b to d) MM14 cells were cotransfected with a CMV-LacZ expression vector and either pBS SK(+) (b), Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) (c), or Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) and dominant negative PKCζ (2 μg/well) (d) plasmids. All cells were maintained for 48 h under G (growth) or D (differentiation) conditions as indicated (a to d). Cultures were fixed and the transfected cells were identified by β-galactosidase staining as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase-positive myotubes (arrows) or unfused cells (arrowheads) are indicated. (e) MM14 cells were cotransfected with a CMV-LacZ expression vector and with Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well)- and dominant negative PKCζ (2 μg/well)-encoding vectors or a control (pcDNA3; 2 μg/well). The cells were fixed and stained as described above. Transfected cells were scored for myoblast fusion. Data shown are the means and standard deviations of four triplicate experiments. No fewer than 1,200 nuclei were counted per point.

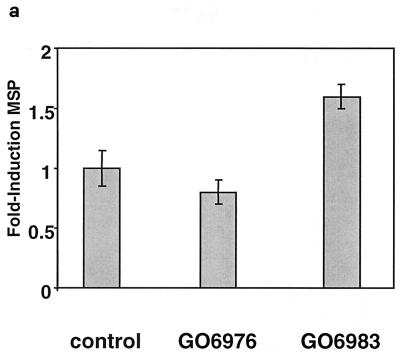

To independently demonstrate that aPKCs are involved in mediating repression of MM14 cell differentiation downstream of Ras, we treated cells with an array of PKC inhibitors with specificity for distinct subsets of PKC isoforms. Treatment of MM14 cells expressing Ha-Ras with GO6976 (100 nM), an inhibitor of PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCμ (13), elicited no detectable effect on muscle gene expression. However, treatment with GO6983, an inhibitor of PKCα, PKCβ, PKCγ, PKCδ, and PKCζ (13) increased muscle gene expression 1.5-fold over control levels, but only at high concentrations of inhibitor (100 μM) that are required to inhibit PKCζ (13) (Fig. 6a). Similarly, treatment of Ha-Ras-expressing MM14 cells with GO6983 (100 nM) increased myoblast fusion while treatment with GO6976 or GF109203X (a broad-specificity kinase inhibitor [32]) or long-term tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate exposure, which down regulates the conventional and novel PKC isoforms (5), did not detectably increase myotube formation (Fig. 6b). Together, these data suggest a direct involvement of PKCζ and/or PKCλ in repressing myogenic differentiation downstream of Ras.

FIG. 6.

Treatment of cells with an aPKC-specific inhibitor induces myogenic differentiation. (a) MM14 cells were cotransfected with the MSP reporter, a CMV-LacZ expression vector, and an Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) plasmid and maintained without FGF-2. Pharmaceutical agents or the vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) was added 1 h after transfection. Cells were assayed as described for Fig. 1, and the data shown are the means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. (b) MM14 cells were cotransfected with a CMV-LacZ expression vector and with the Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) plasmid and maintained under G (growth) or D (differentiation) conditions as indicated. Pharmaceutical agents or vehicle (DMSO) was added 1 h after transfection. The cells were assayed as described for Fig. 5, and the data shown are the means and standard deviations of four triplicate experiments. No fewer than 1,200 nuclei were counted per point.

Although a significant enhancement of muscle gene expression was seen with both mutant aPKCs and the PKCζ inhibitor, the levels of myoblast fusion obtained with either the PKCζ inhibitor or ectopic expression of dominant negative aPKCs were lower than that observed in control cells under differentiation conditions. Therefore, it is likely that additional signaling cascades are involved in repressing myogenesis. We hypothesized that proliferative signals sent via Ha-Ras may indirectly contribute to the inhibition of myogenic differentiation. Consistent with this hypothesis, we have demonstrated that activation of the Raf/MKK1,2/ERK1,2 cascade in MM14 cells is necessary for stimulating proliferation but does not directly inhibit myogenic differentiation (14). We then asked if proliferative signals sent via Ha-RasG12V might indirectly function to repress myogenesis and thus reduce the levels of muscle-specific reporter expression and myotube formation when aPKCs are inhibited.

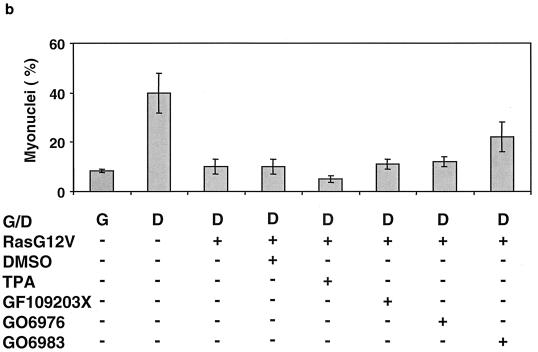

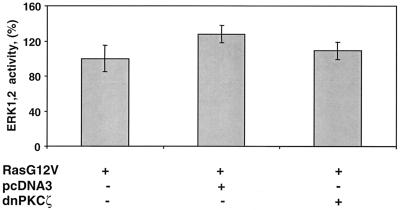

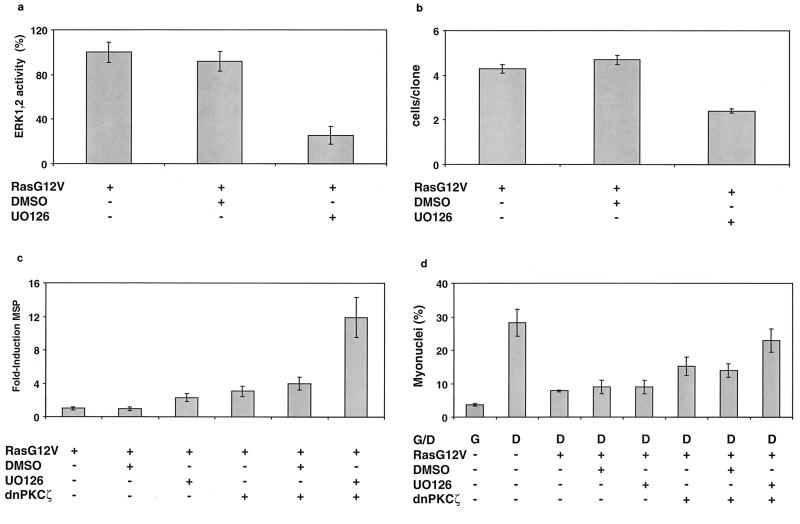

Ectopic expression of Ha-Ras increases ERK1,2 activity five- to sevenfold in MM14 cells as determined by an Elk reporter assay (data not shown). Consistent with previous results demonstrating that the signaling cascades stimulating cell proliferation and repressing myogenesis operate independently, cotransfection of expression vectors encoding the dominant negative PKCζ and Ha-RasG12V does not inhibit Ha-RasG12V-stimulated Elk1 reporter activity (Fig. 7)(10, 14, 19). Moreover, these data show that, unlike some other cell types, skeletal muscle cells do not require activation of aPKCs for Ha-Ras-dependent ERK1,2 activation. Because signals stimulating myoblast proliferation and repressing terminal differentiation are distinct but are both required to maintain dividing cells, we suspected that proliferative signals may indirectly enhance repression of myogenesis. To test for such an indirect role of cell proliferation, myoblast proliferation was first inhibited by blocking the Raf/MKK1,2/ERK1,2 pathway. In the presence of Ha-RasG12V, addition of U0126 (a MKK1,2 inhibitor) blocked both ERK1,2 activity (Fig. 8a) and cell proliferation (Fig. 8b). Consistent with our previous data showing that inhibition of the Raf/MKK1,2/ERK1,2 pathway does not directly affect myogenesis (14), addition of U0126 had little effect on muscle gene expression in the presence of activated Ha-Ras (Fig. 8c). However, addition of U0126 to cells coexpressing constitutively active Ha-Ras and the dnPKCζ mutant synergistically enhanced muscle gene induction (Fig. 8c). In the myoblast fusion assay, the combined effect of UO126 and the dnPKCζ was comparable to the results obtained under differentiation conditions (Fig. 8d). These data suggest that activated Ha-Ras represses myogenesis directly via an aPKC-dependent pathway but also indirectly via stimulation of cell proliferation pathways.

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of aPKC activity has no detectable effect on MAP kinase activation by Ha-RasG12V. MM14 cells were cotransfected with the pFE-Elk1/pFR-Luc reporter system, a CMV-LacZ expression vector, and either Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) and dominant negative PKCζ (2 μg/well) plasmids or a control plasmid (pcDNA3; 2 μg/well). The cells were assayed as described for Fig. 1. The data shown were normalized to Ha-RasG12V-transfected cells and are the means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated twice with comparable results.

FIG. 8.

Inhibition of cell proliferation by the MKK1,2 inhibitor UO126 synergistically enhances dominant negative PKCζ-induced cell differentiation. (a) MM14 cells were cotransfected with the pFE-Elk1/pFR-Luc reporter system, a CMV-LacZ expression vector, and the Ha-RasG12V plasmid (1 μg/well). UO126 or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) was added 1 h after the transfection. The cells were assayed as described for Fig. 1. The data shown are the means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. (b) MM14 cells were cotransfected with CMV-LacZ- and Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well)-encoding plasmids. The cells were replated at clonal density 1 h after transfection, and UO126 or vehicle (DMSO) was added 1 h later. Cultures were fixed, the transfected cells were identified by β-galactosidase staining as described in Materials and Methods, and the number of cells per transfected clone was scored. Data shown are the means and confidence intervals (P = 0.05) of three triplicate experiments. No fewer than 75 clones were counted per point. (c) MM14 cells were cotransfected with the MSP reporter, a CMV-LacZ expression vector, Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well), and dominant negative PKCζ (2 μg/well) plasmids. UO126 or vehicle (DMSO) was added 1 h after the transfection. The cells were assayed as described for Fig. 1, and the data shown are the means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. (d) MM14 cells were cotransfected with a CMV-LacZ expression vector, Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) and dominant negative PKCζ (2 μg/well) plasmids. UO126 or vehicle (DMSO) was added 1 h after the transfection. Cells were assayed as described for Fig. 5, and the data shown are the means and standard deviations of four triplicate experiments. No fewer than 1,200 nuclei were counted per point.

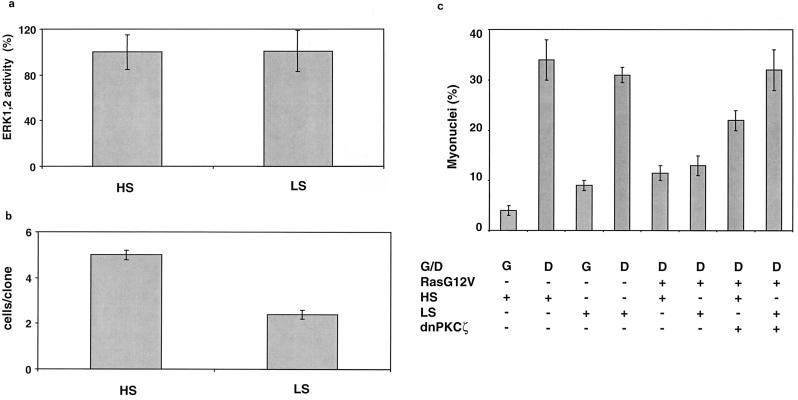

If ERK1,2 is not directly involved in repressing myogenesis, then inhibition of proliferation by a different mechanism that does not affect ERK1,2 activity should also enhance differentiation only when aPKCs are inhibited. To test this, we reduced the serum content of the media to prevent proliferation, which does not affect ERK1,2 activity (Fig. 9a) but blocks cell proliferation (Fig. 9b). In the presence of either exogenously added FGF-2 or ectopic Ha-Ras, serum reduction does not affect myoblast fusion, indicating that both signal directly to repress myogenesis (Fig. 9c). When cells expressing Ha-RasG12V were cultured under low-serum conditions and cotransfected with the mutant PKCζ expression vector, an enhancement of myogenesis similar to that observed on inhibition of ERK1,2 was seen (Fig. 9c). These data confirm our hypothesis suggesting that proliferative signals sent via Ha-RasG12V or serum participate to indirectly inhibit myogenesis. When cell proliferation was eliminated, the effect of the dnPKCζ or aPKC mutants was dramatically enhanced. Therefore, the direct effect of aPKCs in repressing myogenesis appears to be indirectly modulated by proliferative signals sent via Ha-RasG12V or serum.

FIG. 9.

Inhibition of cell proliferation by serum reduction synergistically enhances dominant negative PKCζ-induced cell differentiation. (a) MM14 cells were cotransfected with the pFE-Elk1/pFR-Luc reporter system, CMV-LacZ, and Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) plasmids. The cells were then incubated in 15% (HS) or 2.5% (LS) serum. They were assayed as described for Fig. 1, and the data shown are the means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments from one representative transfection. The experiment was repeated twice with comparable results. (b) MM14 cells were cotransfected with a CMV-LacZ expression vector and with the Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) plasmid. They were replated at clonal density 1 h after the transfection was begun. They were assayed as described for Fig. 8b, and the data shown are the means and confidence intervals (P = 0.05) of four triplicate experiments. No fewer than 75 clones were counted per point. (c) MM14 cells were cotransfected with a CMV-LacZ expression vector and with Ha-RasG12V (1 μg/well) and dominant negative PKCζ (2 μg/well) plasmids. They were then incubated in 15 or 2.5% serum for 48 h. They were assayed as described for Fig. 3, and the data shown are the means and standard deviations of three experiments performed in triplicate. No fewer than 1,200 nuclei were counted per point.

DISCUSSION

The Ras family of GTPases are crucial molecular transducers that relay signals generated from receptor protein tyrosine kinases to multiple downstream signaling cascades. Constitutively activated mutants of Ras play important roles in the onset of numerous human cancers, including those originating from muscle tissues. Ha-Ras mutations are detected in up to 35% of human rhabdomyosarcomas (30), tumors generated by proliferating skeletal muscle cells. As a result of oncogenic transformation, cells of these tumors acquire a growth advantage and a reduction or loss in differentiation potential. A number of studies have demonstrated the ability of oncogenic Ha-Ras to inhibit skeletal muscle differentiation, yet none of the known Ha-Ras effectors that mediate the repression of myogenic differentiation have been identified (17, 22, 25-27).

In this study we have identified a downstream component of the Ha-Ras signal transduction pathway that represses the differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. Several derivatives of oncogenic Ha-Ras mutants, including Ha-RasG12S35, Ha-RasG12C40, and Ha-RasG12G37 (16, 34), are capable of replacing endogenous FGF-dependent signals and repressing MM14 myoblast differentiation. Therefore, our data suggest that Raf, PI3-K, and Ral are not the downstream Ha-Ras effectors that mediate the repression of myogenic differentiation. Similar results have been previously observed for serum-mediated repression of myogenesis, but the growth factor signaling pathways involved were not identified (22, 26, 27). Interestingly, Ha-RasG12V also stimulates myoblast proliferation (10); however, none of these three Ha-Ras effector mutants, either alone or in combination, are sufficient to stimulate myoblast proliferation (Y. V. Fedorov et al., unpublished observation). Thus, oncogenic Ha-Ras appears to regulate myoblast differentiation and proliferation through multiple, independent signaling pathways. Since recent reports have demonstrated that PKCζ and Ha-Ras interact directly with each other, it is possible that aPKCs are direct effectors for Ras (7). In support of the involvement of aPKCs in Ras signaling, PKCζ is required for Ha-Ras-dependent maturation of Xenopus oocytes, for serum-activated DNA synthesis in mouse fibroblasts (2, 8), and for Ha-Ras-dependent induction of c-Fos (15).

Here we show that interference with aPKC signaling either by overexpressing a dominant negative mutant of PKCζ or PKCλ or by treating cells with a pharmaceutical inhibitor of aPKCs abrogates Ha-RasG12V-mediated repression of myogenesis. Together, these data demonstrate that aPKCs are required for Ha-Ras-mediated repression of myogenic differentiation and that the aPKCs function as downstream Ha-Ras effectors in a signaling cascade that represses myogenic differentiation. Although blocking aPKC signaling enhances myogenic differentiation, the extent of differentiation was often less than that observed under differentiation conditions. Since proliferation and terminal differentiation are mutually exclusive events and since we have previously shown that Ha-RasG12V promotes MM14 cell proliferation, we asked if proliferation signals indirectly repressed myogenesis. Two independent methods were used to block cell proliferation: inhibition of the Raf/MKK1,2/ERK1,2 pathway and reduction of the serum concentration. Although inhibition of the Raf/MKK1,2/MAPK pathway does not stimulate the differentiation of parental or of Ha-RasG12V expressing cells, it does block cell proliferation (14). Surprisingly, we found that inhibition of Ha-Ras/MAP kinase pathways has a synergistic effect on enhancement of the differentiation of MM14 cells when aPKCs are inhibited. Similarly, inhibition of cell proliferation by reducing the serum concentration from 15 to 2.5% also synergistically enhanced myogenesis when aPKCs were inhibited. These data support a direct role for aPKCs in transducing Ha-Ras signals that repress myogenesis and suggest that proliferative signals can enhance the repression of differentiation only if the direct repressive signals are present. Thus, consistent with our previous results, it is unlikely that ERK1,2 is directly involved in regulating myogenesis since ectopic expression of a dominant negative PKCζ mutant had no effect on Ha-RasG12V-mediated increase of ERK1,2 activity. We propose that aPKCs are direct mediators of Ras signals that function to repress myogenic differentiation in proliferating and quiescent cells.

The specific molecular events that regulate proliferation and myogenesis in satellite cells are largely unknown. However, of particular interest is the observation that aPKCs interact directly with the FGF receptor substrate SNT (FRS-2) (20). FGFs are established regulators of myogenesis and are required for the development and maintenance of embryonic myoblasts in vivo (11), for growth of primary mouse myoblasts (21, 28), and for muscle satellite cell viability (unpublished data). These data illustrate that the relationship between aPKC interaction with Ha-Ras and SNTs is complex and may involve multiple downstream pathways. One possible scenario could provide activation of aPKCs by localizing both Ras and an aPKC to FGF receptor 1 via an SNT scaffold following FGF binding. Activation of the aPKCs would then promote their translocation to distinct subcellular compartments, reported to correlate with PKC activation. Consistent with aPKC activation by Ras, we found that ectopic expression of RasG12V stimulated the translocation of PKCλ from the cytosol to the nucleus. Although RasG12V stimulated the nuclear localization of PKCλ but had no apparent effect on the localization of PKCζ, PKC translocation is a dynamic process where both association and dissociation with or from subcellular compartments appears to be important (21). Therefore, the data do not preclude the involvement of either aPKC, and additional experiments are needed to identify which protein is involved in Ras signaling.

We propose that oncogenic Ha-Ras represses differentiation directly through an aPKC-dependent pathway(s) and indirectly through stimulation of cell proliferation. Inhibition of two independent Ha-Ras signaling pathways, one inhibiting differentiation and the second promoting proliferation, is necessary for myoblasts to completely commit to terminal differentiation. Further experimentation is aimed at identifying the aPKC substrates involved and their contribution to repression of myogenesis via FGF-dependent pathways.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge a gift of expression vectors made by Chaning Der, Silvio J. Gutkind, and Robert V. Farese.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AR39467) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association to B.B.O.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandyopadhyay, G., M. L. Standaert, U. Kikkawa, Y. Ono, J. Moscat, and R. V. Farese. 1999. Effects of transiently expressed atypical (zeta, lambda), conventional (alpha, beta) and novel (delta, epsilon) protein kinase C isoforms on insulin-stimulated translocation of epitope-tagged GLUT4 glucose transporters in rat adipocytes: specific interchangeable effects of protein kinases C-zeta and C-lambda. Biochem. J. 337:461-470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berra, E., M. T. Diaz-Meco, I. Dominguez, M. M. Municio, L. Sanz, J. Lozano, R. S. Chapkin, and J. Moscat. 1993. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for mitogenic signal transduction. Cell 74:555-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell, S. L., R. Khosravi-Far, K. L. Rossman, G. J. Clark, and C. J. Der. 1998. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene 17:1395-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clegg, C. H., T. A. Linkhart, B. B. Olwin, and S. D. Hauschka. 1987. Growth factor control of skeletal muscle differentiation: commitment to terminal differentiation occurs in G1 phase and is repressed by fibroblast growth factor. J. Cell Biol. 105:949-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper, D. R., J. E. Watson, M. Acevedo-Duncan, R. J. Pollet, M. L. Standaert, and R. V. Farese. 1989. Retention of specific protein kinase C isozymes following chronic phorbol ester treatment in BC3H-1 myocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 161:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo, P., H. Mischak, and J. S. Gutkind. 1995. Overexpression of mammalian protein kinase C-zeta does not affect the growth characteristics of NIH 3T3 cells Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 213:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz-Meco, M. T., J. Lozano, M. M. Municio, E. Berra, S. Frutos, L. Sanz, and J. Moscat. 1994. Evidence for the in vitro and in vivo interaction of Ras with protein kinase C zeta. J. Biol. Chem. 269:31706-31710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez, I., M. T. Diaz-Meco, M. M. Municio, E. Berra, A. Garcia de Herreros, M. E. Cornet, L. Sanz, and J. Moscat. 1992. Evidence for a role of protein kinase C zeta subspecies in maturation of Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3776-3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedorov, Y. V., N. C. Jones, and B. B. Olwin. 1998. Regulation of myogenesis by fibroblast growth factors requires beta- gamma subunits of pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5780-5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedorov, Y. V., R. S. Rosenthal, and B. B. Olwin. 2001. Oncogenic ras-induced proliferation requires autocrine fibroblast growth factor 2 signaling in skeletal muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 152:1301-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanagan-Steet, H., K. Hannon, M. J. McAvoy, R. Hullinger, and B. B. Olwin. 2000. Loss of FGF receptor 1 signaling reduces skeletal muscle mass and disrupts myofiber organization in the developing limb. Dev. Biol. 218:21-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Paramio, P., Y. Cabrerizo, F. Bornancin, P. J. Parker, D. Toullec, P. Pianetti, H. Coste, P. Bellevergue, T. Grand-Perret, M. Ajakane, V. Baudet, P. Boissin, E. Boursier, F. Loriolle, et al. 1998. The broad specificity of dominant inhibitory protein kinase C mutants infers a common step in phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 333:631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gschwendt, M., S. Dieterich, J. Rennecke, W. Kittstein, H. J. Mueller, F. J. Johannes, G. Bandyopadhyay, M. L. Standaert, U. Kikkawa, Y. Ono, J. Moscat, and R. V. Farese. 1996. Inhibition of protein kinase C mu by various inhibitors. Differentiation from protein kinase c isoenzymes. FEBS Lett. 392:77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, N. C., Y. V. Fedorov, R. S. Rosenthal, and B. B. Olwin. 2001. ERK1/2 is required for myoblast proliferation but is dispensable for muscle gene expression and cell fusion. J. Cell. Physiol. 186:104-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kampfer, S., K. Hellbert, A. Villunger, W. Doppler, G. Baier, H. H. Grunicke, F. Uberall, G. Bandyopadhyay, M. L. Standaert, U. Kikkawa, Y. Ono, J. Moscat, and R. V. Farese. 1998. Transcriptional activation of c-fos by oncogenic Ha-Ras in mouse mammary epithelial cells requires the combined activities of PKC-lambda, epsilon and zeta. EMBO J. 17:4046-4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khosravi-Far, R., M. A. White, J. K. Westwick, P. A. Solski, M. Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, L. Van Aelst, M. H. Wigler, and C. J. Der. 1996. Oncogenic Ras activation of Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathways is sufficient to cause tumorigenic transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3923-3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konieczny, S. F., B. L. Drobes, S. L. Menke, and E. J. Taparowsky. 1989. Inhibition of myogenic differentiation by the H-ras oncogene is associated with the down regulation of the MyoD1 gene. Oncogene 4:473-481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kudla, A. J., M. L. John, D. F. Bowen-Pope, B. Rainish, and B. B. Olwin. 1995. A requirement for fibroblast growth factor in regulation of skeletal muscle growth and differentiation cannot be replaced by activation of platelet-derived growth factor signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3238-3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudla, A. J., N. C. Jones, R. S. Rosenthal, K. Arthur, K. L. Clase, and B. B. Olwin. 1998. The FGF receptor-1 tyrosine kinase domain regulates myogenesis but is not sufficient to stimulate proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 142:241-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim, Y. P., B. C. Low, J. Lim, E. S. Wong, and G. R. Guy. 1999. Association of atypical protein kinase C isotypes with the docker protein FRS2 in fibroblast growth factor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 274:19025-19034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linkhart, T. A., C. H. Clegg, and S. D. Hauschka. 1980. Control of mouse myoblast commitment to terminal differentiation by mitogens. J. Supramol. Struct. 14:483-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitin, N., A. J. Kudla, S. F. Konieczny, and E. J. Taparowsky. 2001. Differential effects of Ras signaling through NFkappaB on skeletal myogenesis. Oncogene 20:1276-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishizuka, Y., F. Uberall, K. Hellbert, S. Kampfer, K. Maly, A. Villunger, M. Spitaler, J. Mwanjewe, G. Baier-Bitterlich, G. Baier, and H. H. Grunicke. 1992. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science 258:607-614.1411571 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishizuka, Y., F. Uberall, K. Hellbert, S. Kampfer, K. Maly, A. Villunger, M. Spitaler, J. Mwanjewe, G. Baier-Bitterlich, G. Baier, and H. H. Grunicke. 1995. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 9:484-496.7737456 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson, E. N., G. Spizz, and M. A. Tainsky. 1987. The oncogenic forms of N-ras or H-ras prevent skeletal myoblast differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2104-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramocki, M. B., S. E. Johnson, M. A. White, C. L. Ashendel, S. F. Konieczny, and E. J. Taparowsky. 1997. Signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinase and Rac/Rho does not duplicate the effects of activated Ras on skeletal myogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3547-3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramocki, M. B., M. A. White, S. F. Konieczny, and E. J. Taparowsky. 1998. A role for RalGDS and a novel Ras effector in the Ras-mediated inhibition of skeletal myogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17696-17701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rando, T. A., and H. M. Blau. 1994. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy J. Cell Biol. 125:1275-1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanes, J. R., J. L. Rubenstein, J. F. Nicolas, G. Bandyopadhyay, M. L. Standaert, U. Kikkawa, Y. Ono, J. Moscat, and R. V. Farese. 1986. Use of a recombinant retrovirus to study post-implantation cell lineage in mouse embryos. EMBO J. 5:3133-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stratton, M. R., C. Fisher, B. A. Gusterson, and C. S. Cooper. 1989. Detection of point mutations in N-ras and K-ras genes of human embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas using oligonucleotide probes and the polymerase chain reaction. Cancer Res. 49:6324-6327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toker, A., F. Uberall, K. Hellbert, S. Kampfer, K. Maly, A. Villunger, M. Spitaler, J. Mwanjewe, G. Baier-Bitterlich, G. Baier, and H. H. Grunicke. 1998. Signaling through protein kinase C. Front. Biosci. 3:D1134-D1147.9792904 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toullec, D., P. Pianetti, H. Coste, P. Bellevergue, T. Grand-Perret, M. Ajakane, V. Baudet, P. Boissin, E. Boursier, F. Loriolle, et al. 1991. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15771-15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uberall, F., K. Hellbert, S. Kampfer, K. Maly, A. Villunger, M. Spitaler, J. Mwanjewe, G. Baier-Bitterlich, G. Baier, and H. H. Grunicke. 1999. Evidence that atypical protein kinase C-lambda and atypical protein kinase C-zeta participate in Ras-mediated reorganization of the F-actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 144:413-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White, M. A., C. Nicolette, A. Minden, A. Polverino, L. Van Aelst, M. Karin, and M. H. Wigler. 1995. Multiple Ras functions can contribute to mammalian cell transformation. Cell 80:533-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, S., and M. H. Cobb. 1997. MEKK1 binds directly to the c-Jun N-terminal kinases/stress-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 272:32056-32060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]