Abstract

SAF-1, a zinc finger transcription factor, is activated by a number of inflammatory agents, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6. It is involved in the cytokine-mediated transcriptional induction of serum amyloid A, an acute-phase plasma protein that is associated with the pathogenesis of reactive amyloidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis. Here, we show that the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathway regulates cytokine-mediated induction of the DNA-binding activity and transactivation potential of SAF-1. Phosphorylation of endogenous SAF-1 in response to IL-1 and IL-6 was markedly inhibited by the addition of MAP kinase inhibitors. Consistent with this finding, we show that a consensus MAP kinase phosphorylation site, PPTP, within SAF-1 could be phosphorylated by MAP kinase in vitro. To analyze the contribution of MAP kinase in the activation of SAF-1, we prepared two independent mutant proteins in which the threonine residue of the PPTP motif was altered to either valine or alanine. These mutant proteins lost the ability to be phosphorylated by MAP kinase both in vivo and in vitro and exhibited a significantly reduced ability to promote expression of the SAF-1-regulated promoter. While the DNA-binding activity of wild-type SAF-1 protein was markedly increased upon phosphorylation with MAP kinase, no such increase could be detected with the mutant SAF-1 proteins. Further analysis with the GAL-4 reporter system showed that mutation of the MAP kinase phosphorylation site considerably lowers the transactivation potential of SAF-1. Together, these results show that activation of SAF-1 in response to IL-1 and -6 is mediated via MAP kinase-regulated phosphorylation.

Serum amyloid A (SAA) protein, a member of the acute-phase protein group, is induced up to 1,000-fold during periods of inflammation, mostly due to transcriptional induction of the gene that encodes it (28, 52, 56). Overexpression of SAA during chronic inflammatory periods is linked to the pathophysiology of amyloidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis (8, 10, 20, 27, 31, 32, 52, 53, 56). Proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha, either alone or in combination, and many other inflammatory mediators, namely, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, bacterial lipopolysaccharide, and minimally modified low-density lipoprotein, can increase transcription of the gene for SAA (3, 13, 30, 40, 46). Regulation of SAA gene expression has been studied and characterized by different groups, including ours (3, 13, 19, 26, 40, 41, 42, 46). Multiple cis-acting elements have been found to be important for transcriptional induction of SAA genes, including C/EBP, NF-κB, YY-I, Sp1, and SAF transcription factor DNA-binding elements. Although SAA biosynthesis takes place mostly in the liver, nonhepatic expression of this protein appears to be important because many pathological conditions, such as amyloidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis, that are linked to abnormal SAA expression are manifested in nonhepatic organs. Induction of the rabbit gene for SAA2 in nonhepatic tissues is regulated primarily by activation of the SAF family of transcription factors, which contain multiple Cys2-His2-type zinc fingers at the C-terminal end (44). A member of this family, SAF-1, shows a high degree of homology with MAZ/Pur-1 proteins, and this suggests that SAF-1 is a member of the MAZ/Pur-1 family of transcription factors (6, 22). Members of the SAF-1/MAZ/Pur-1 family of proteins are involved in the regulation of a variety of genes, including those for SAA, c-myc, insulin, CD4, the serotonin 1A receptor, γ-fibrinogen, CLC-K1, and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (6, 12, 18, 22, 36, 38, 44, 55). SAF-1 DNA-binding activity is normally detected in many tissues at a low level, but many inflammatory agents, including lipopolysaccharide (48), IL-1, IL-6 (45), and minimally modified low-density lipoprotein (46), are known to increase its DNA-binding activity and overall transactivating potential. In a recent study, we have shown that protein kinase C β regulates phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-mediated activation of SAF-1 (39). As different inflammatory agents are known to activate different signaling pathways, it is likely that an additional protein kinase(s) is involved in the regulation of SAF activity in response to diverse inflammatory agents.

The mechanisms by which SAF-1 and other members of its family are activated in response to IL-1 and IL-6 are unclear. The present study was undertaken to address this aspect. IL-1 and IL-6, in conjunction with tumor necrosis factor alpha, have been found to participate in the induction of a broad group of acute-phase proteins during periods of inflammation (16). The effector cascades through which IL-1 and IL-6 mediate their regulatory response have been elucidated, at least in part, and shown to include the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signal transduction pathways (1, 5, 9, 11, 17, 21, 23, 25, 35, 37, 51, 54). MAP kinases are a family of protein serine/threonine kinases that are activated in response to various extracellular stimuli and mediate signal transduction from the cell surface to the nucleus. In mammalian cells, three major MAP kinase pathways have been identified (reviewed in reference 9). These include the ERK (p42/p44 MAPK), JNK/SAPK, and p38MAPK group of proteins. Due to considerable structural similarities, multiple MAP kinase pathways are often activated by the same stimulus. However, there are many instances that show that each MAP kinase pathway has its own regulatory features that allow each member to be unique.

The amino acid sequence P-X-S/T-P, in which X is any amino acid, has been identified as a consensus MAP kinase recognition site in which either S or T is the phosphorylation site (2). The SAF-1 protein contains a PAPPPTPQAP sequence at its amino-terminal end that can act as a potential MAP kinase phosphorylation site. In the present report, we show that inhibitors of the MAP kinase signaling pathway markedly reduce expression of SAF-regulated promoters. Furthermore, by using two forms of SAF-1 with mutations at the MAP kinase phosphorylation site, we show that both the DNA-binding and transactivating abilities of SAF-1 are regulated by MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection experiments.

HIG82 (rabbit synoviocyte) and HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing a high concentration of glucose (4.5 g/liter) and supplemented with 7% fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method (50). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested. All transfections were carried out with a mixture of plasmid DNAs, as indicated in the figure legends, and a carrier plasmid DNA so that the total amount of DNA in each transfection assay remained constant. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity was determined as described before (44).

Plasmids.

An SAF-CAT reporter plasmid was constructed by ligating three tandem copies of the SAF DNA-binding element, bp −254 to −226 of the SAA promoter (48), into plasmid vector pBLCAT2 (29). Plasmid pCMVFLAG-SAF1 was prepared by first attaching, in frame, the FLAG epitope at the N terminus of the full-length SAF-1 cDNA; the resulting FLAG-SAF1 cDNA was further subcloned in vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen).

Mutagenesis and production of bacterium expressed wild-type and mutant SAF-1 proteins.

Threonine-to-alanine and threonine-to-valine substitution mutant proteins were generated by megaprimer PCR using appropriate oligonucleotides approximately 35 bp in length. In order to effectively amplify the GC-rich sequences present in the SAF-1 sequence, GC-melt (CLONTECH) was added to the PCR mixture. The PCR products were subcloned in vector pTZ19U (U.S. Biological Corp.) and sequenced for verification of mutations. A FLAG epitope was attached at the N-terminal end prior to subcloning in the pcDNA3 vector for expression in eukaryotic cells.

For bacterial expression and preparation of proteins, wild-type SAF1 cDNA and mutant SAF1 cDNAs were subcloned in vector pAR(ΔR1)59/60 (4), which contains a FLAG epitope and a heart muscle kinase phosphorylation site. The recombinant proteins were produced in bacterial strain BL21(DE3)pLysS. Briefly, after cell growth to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added (1 mM final concentration) to induce protein synthesis and cells were grown for another 4 h. Recombinant proteins were purified with an anti-FLAG antibody column (Sigma Chemical Co.).

Construction of a chimeric GAL4-SAF1 plasmid.

Plasmid RSV-GAL4DBD (15), encoding the DNA-binding domain of GAL4 (amino acids 1 to 147), driven by the Rous sarcoma virus promoter, and followed by a BamHI site, was used to prepare a GAL4-SAF1 construct. The wild type and two substitution mutant forms, threonine to alanine and threonine to valine, of the full-length SAF-1 cDNA were fused in frame C terminal to GAL4 amino acids 1 to 147 at the BamHI site. The resulting RSV-GAL4DBD-SAF1 plasmid and mutant derivative clones were subjected to DNA sequencing to verify in-frame coding of the fusion protein. A reporter CAT-encoding gene with minimum basal activity and three tandem copies of the GAL4 binding element, known as the upstream activating sequence (UAS), was used to monitor the transactivation potential of the chimeric proteins.

In vitro phosphorylation and immunoprecipitation.

The phosphorylation reaction was performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-10 mM MgCl2-100 μM unlabeled ATP-10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol)-0.1 μg of affinity-purified FLAG epitope-containing wild-type and mutant SAF-1 protein or 20 to 50 ng of synthetic SAF-1 peptide-1.0 U of purified MAP kinase (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp.) at 30°C for 30 min in a total volume of 50 μl. Phosphorylated synthetic SAF peptide was fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-14% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and 32P-labeled phosphopeptide was detected by autoradiography. The samples containing the FLAG epitope-tagged SAF protein were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma Chemical Co.) by gentle agitation at 4°C for 16 h in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% [vol/vol] NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 2.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mg of benzamidine per ml). Next, 50 μl of protein G-agarose beads (Boehringer Mannheim) was added and the mixture was further incubated for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed five times with immunoprecipitation buffer, resuspended in 10 μl of SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol), and boiled for 10 min prior to SDS-11% PAGE.

To determine the target amino acid in the 32P-labeled phosphopeptide that is phosphorylated by MAP kinase, the radioactive phosphopeptide was excised from the dry polyacrylamide gel, eluted with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 7.8)-0.1% SDS-5% β-mercaptoethanol, and precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. The phosphopeptide was completely hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl at 110°C for 2 h. Phosphoamino acids were separated by thin-layer chromatography and detected by autoradiography, and their migration positions were compared with those of authentic phosphoamino acid markers.

In vivo phosphorylation and immunoprecipitation.

HIG82 and HepG2 cells were grown in cultures in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum for 24 h. The cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (0.5 mCi/ml) in phosphate-free DMEM for 8 h with or without cytokines, a combination of IL-1β (200 U/ml) and IL-6 (500 U/ml) and MAP kinase inhibitors as indicated. Some cells received a 20 μM concentration of either PD98059, SB203580, or SB202474. In a separate in vivo phosphorylation of SAF-1, HIG82 cells were transfected with either wild-type SAF-1 or two mutant derivatives, SAF-1(V71) and SAF-1(A71). In addition, some transfection reaction mixtures contained a MAP kinase (ERK1) expression plasmid (provided by M. Cobb). Forty hours after transfection, the cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate as described above. After labeling, the 32P-labeled cells were washed quickly in phosphate-free DMEM and lysed by addition of hot lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 1% NP-40, 3 mM vanadate, 2.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The lysates were collected in microcentrifuge tubes and heated at 95°C, and the SDS concentration was reduced to 0.05% by addition of lysis buffer without SDS. The 32P-labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-SAF1 antibody or preimmune serum by incubation of the mixture for 16 h at 4°C. Next, protein G-Sepharose beads (Boehringer Mannheim) were added and the mixture was further incubated for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were extensively washed, resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer, and boiled for 10 min. The samples were analyzed by SDS-11% PAGE and autoradiographed.

Nuclear extracts and EMSA.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described earlier (47) from HIG82 and HepG2 cells that were treated with various agents as described in the figure legends and elsewhere in the text. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed with nuclear extracts containing equal protein amounts as described previously (47). Protein concentrations were measured by Bradford's method (7). Bacterium-expressed and affinity-purified FLAG-SAF1 proteins, both wild-type and mutant forms, were used in the EMSA as the source of DNA-binding factor. For antibody interaction studies, anti-SAF1 serum (48) and anti-FLAG serum (Sigma Chemical Co.) were added to the reaction mixture during preincubation for 30 min on ice. Radiolabeled probes were prepared by incorporating 32P at the double-stranded SAF DNA-binding element. Two complementary oligonucleotides, 5"-GGCTTCCTCTCCACC-3" and 3"-CGAAGGAGAGGTGGG-5", were annealed to prepare the double-stranded SAF DNA-binding element.

Bacterium-expressed wild-type and mutant SAF-1 proteins (0.1 μg) were phosphorylated with 1.0 U of activated mouse MAP kinase (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp.) in a volume of 10 μl. After phosphorylation, proteins were incubated with the radioactive SAF DNA-binding element probe in accordance with the EMSA procedure described earlier (39). In some reaction mixtures, SB220025 (200 μM) was added during in vitro phosphorylation of proteins. In some reaction mixtures, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (4 U), with or without phosphatase inhibitors (NaF [50 mM], okadaic acid [5 μM], and sodium orthovanadate [1 mM]), was added during in vitro phosphorylation of the proteins.

Western blot analysis.

Cell lysates (50 μg of protein) prepared from transfected cells were separated by SDS-11% PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with phosphate-buffered saline-0.05% Tween 20 supplemented with 5% nonfat dry milk at room temperature for 2 h. Anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) was diluted 1:1,000 in phosphate-buffered saline-0.05% Tween 20 buffer plus 1% bovine serum albumin, and the membrane was incubated for 24 h in this buffer at 4°C. In some reaction mixtures, anti-SAF1 antibody was used. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody was used as the secondary antibody. Bands were detected by using a chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Life Science Ltd.).

RESULTS

Inhibitors of MAP kinase reduce cytokine-mediated induction of SAF-1 DNA-binding activity and expression of the SAF-1-regulated promoter.

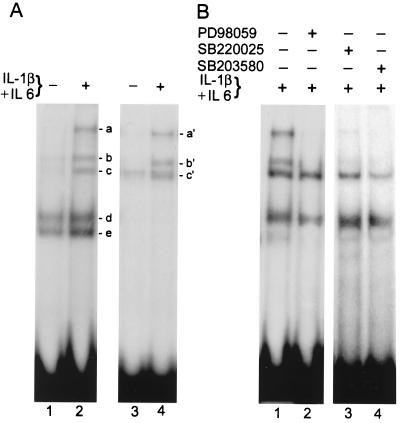

The DNA-binding activity of endogenous SAF family proteins is increased when cells are exposed to IL-1 and IL-6, and this effect is seen in both liver-specific HepG2 and synovial fibroblast HIG82 cells (Fig. 1A). Signaling events triggered by these cytokines are known to activate a protein kinase cascade that subsequently modulates the activity of many downstream substrates, including transcription factors, by phosphorylating these proteins (1, 5, 9, 17, 23, 25, 51, 54). Consistent with this scenario, previous studies in our laboratory have indicated that phosphorylation of SAF family members is necessary for increased DNA-binding activity since phosphatase treatment of nuclear extracts inhibits (43), while the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid potentiates (44), its activity. These studies indicated a possible role for a serine/threonine protein kinase in the phosphorylation of SAF. Since the IL-1β and IL-6 signaling pathways, which activate SAF, involve MAP kinase, we were interested in knowing whether MAP kinase is involved in the elicition of enhanced SAF activity. The flavone compound 2-(2"-amino-3" methoxyphenyl)oxanaphthalen-4-one (PD98059) is a specific inhibitor of mammalian MEK-1/2 and is extensively used to study the physiological role of ERK (p42/44 MAP kinase) (34). When PD98059 was added to the cells, the stimulatory effect of cytokines was abrogated (Fig. 1B, lane 2). While PD98059 is considered a specific inhibitor of ERKs, the pyridinylimidazole compounds 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfonylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (SB203580) and 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (SB202190) are known as specific inhibitors of the p38 MAP kinase group of protein kinases (24, 49). SB220025 is known to inhibit both p38 and p42/44 MAP kinases. Addition of both SB220025 and SB203580 inhibited the DNA-binding ability of endogenous SAF (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4).

FIG. 1.

Cytokine-mediated induction of SAF DNA-binding activity is regulated by MAP kinase inhibitors. Nuclear extracts prepared from HIG82 (panel A, lanes 1 and 2, and panel B, lanes 1 to 4) and HepG2 (panel A, lanes 3 and 4) cells were used in an EMSA with 32P-labeled SAF DNA-binding oligonucleotide as the probe. Where indicated, cells were incubated with IL-1β and IL-6 (200 and 500 U/ml, respectively) for 24 h. MAP kinase inhibitors PD98059 (20μM), SB220025 (200 μM), and SB203580 (20 μM) were included along with the cytokines in some culture media of HIG82 cells (panel B, lanes 2 to 4). Ten micrograms of protein from each nuclear extract was used in the EMSA, which was performed as described in Materials and Methods, and the DNA-protein complexes were resolved in a 6% native polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. The positions of DNA-protein complexes are designated a through e and a" through c".

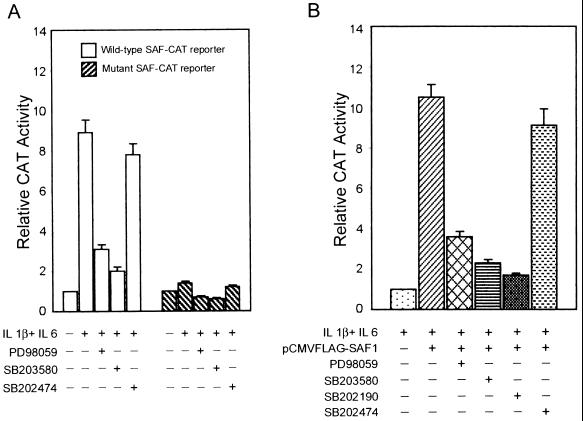

To test whether the MAP kinase signaling pathway affects the transactivation potential of SAF-1, we used CAT-encoding reporter genes (SAF-CAT) containing wild-type or mutant SAF-1 DNA-binding elements and transfected HIG82 synovial cells with this plasmid (Fig. 2A). Addition of cytokines increased wild-type CAT-encoding reporter gene expression but had no effect on the mutant reporter plasmid. MAP kinase inhibitors PD98059, SB203580, and SB202190 markedly inhibited cytokine-induced expression of SAF-CAT. These results indirectly suggested that the MAP kinase pathway is involved in the control of SAF-regulated promoters. For a more direct evaluation, HIG82 cells were transiently cotransfected in duplicate with the SAF-CAT reporter and an expression plasmid containing SAF-1 cDNA (Fig. 2B). Following transfection, one set of cells was incubated with IL-1 plus IL-6 and various MAP kinase inhibitor compounds. As seen in Fig. 2B, increased transcriptional activity of SAF1-transfected cells is a result of overexpressed SAF-1 that is activated by the IL-1 and IL-6 added to the cells. MAP kinase inhibitors PD98059, SB202190, and SB203580 all significantly reduced the transcriptional activity of SAF-1. In contrast, the inactive compound SB202474, which does not block any MAP kinase activity (24), showed no inhibitory effect. It was noticeable that all MAP kinase inhibitors were not as effective at inhibiting SAF-1 function. The most inhibition was seen with SB202190 and SB203580. Together, these results suggest that SAF activity is regulated by MAP kinases.

FIG. 2.

MAP kinase signaling pathway inhibitors reduce the transactivating potential of SAF-1. (A) HIG82 cells were transfected with CAT reporter plasmids (0.5 μg of DNA) containing multiple copies of wild-type or mutant SAF DNA-binding elements. Where indicated, a combination of IL-1β (200 U/ml) and IL-6 (500 U/ml) and MAP kinase inhibitors PD98059 (20 μM), SB203580 (20 μM), and SB202474 (20 μM) was added to the medium. Cells were harvested 48 h after glycerol shock, and CAT activity was measured. The results shown are averages of three separate experiments. (B) HIG82 cells were transfected with 0.5μg of wild-type SAF-CAT reporter plasmid DNA plus 0.1 μg of pCMVFLAG-SAF1 plasmid DNA, as indicated. Following transfection, cells were incubated with IL-1β (200 U/ml) and IL-6 (500 U/ml). Where indicated, MAP kinase inhibitors PD98059, SB03580, SB202190, and SB202474 were added to the medium at a 20 μM concentration. Cells were harvested 48 h after glycerol shock, and CAT activity was measured. The results shown are averages of three separate experiments.

Cytokine stimulation phosphorylates endogenous SAF-1.

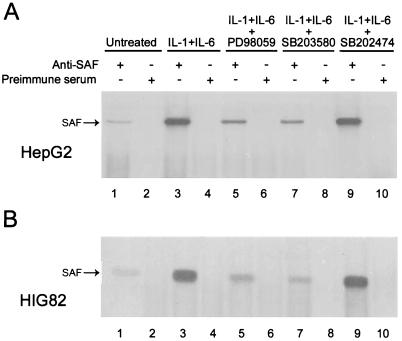

Next, we determined whether IL-1- and IL-6-mediated signaling phosphorylates endogenous SAF-1 and, if so, whether activated MAP kinases are involved in this process. HepG2 and HIG82 cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate. During labeling, cells were stimulated with IL-1 plus IL-6 in the presence or absence of inhibitors of MAP kinases. 32P-labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated by using anti-SAF1 antibody and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A radioactive protein corresponding in size to SAF-1 was specifically present in the lanes containing samples that were immunoprecipitated with anti-SAF1 antibody (Fig. 3,lane 1) but not preimmune serum (lane 2). The intensity of this band was markedly higher in cells stimulated with IL-1 plus IL-6 (lane 3) and much lower when MAP kinase inhibitor PD98059 (lane 5) or SB203580 (lane 7) was added. No reduction in the phosphorylation level of SAF-1 was produced by the inactive compound SB202474 (lane 9). The fact that the SAF-1 protein phosphorylation level was significantly high in cytokine-stimulated cells but lower in the presence of inhibitors of MAP kinase indicated that endogenous SAF-1 protein is phosphorylated by the MAP kinase signaling pathway during stimulation of cells by IL-1 and IL-6. A low level of phosphorylation of SAF is seen in untreated cells (lane 1). Possibly, this is due to a basal level of protein kinase activity in the cultured cells.

FIG. 3.

Hyperphosphorylation of endogenous SAF-1 during cytokine-mediated stimulation of cells. HepG2 and HIG82 cells were grown in duplicate in DMEM plus 5% fetal calf serum for 24 h. Some cells were incubated with IL-1β (200 U/ml) plus IL-6 (500 U/ml) with or without inhibitors of MAP kinase (a 20 μM concentration of each), as indicated. Six hour prior to labeling, cells were switched to phosphate-free DMEM plus 5% fetal calf serum and labeled with 32Pi (0.5 mCi/ml) for 8 h. 32P-labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated with either anti-SAF1 antibody or preimmune serum. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-11% PAGE followed by autoradiography.

A MAP kinase phosphorylation consensus site is present in the SAF-1 protein sequence.

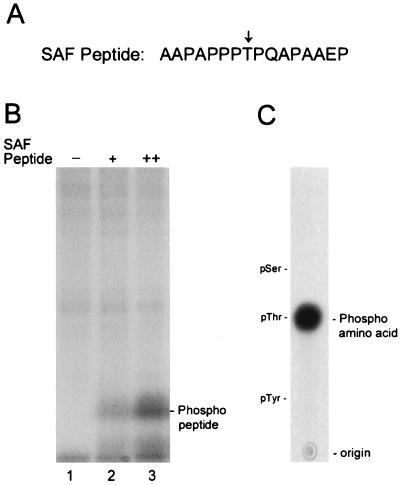

The amino acid sequence motif Pro-X-Thr/Ser-Pro has been identified as a consensus recognition site for MAP kinases (2). Primary sequencing of SAF-1 revealed the existence of an AAPAPPPTPQAPAAEP motif, amino acids 64 to 79 (44), in which Thr-71 could be a potential phosphate acceptor amino acid. We prepared a synthetic peptide (Fig. 4A)containing this sequence, which was in vitro phosphorylated using [γ-32P]ATP, and purified MAP kinase (Fig. 4B). Further analysis revealed threonine as the phosphate acceptor (Fig. 4C). These data suggested that the PPTP sequence motif of SAF-1 is a potential phosphorylation site for MAP kinase.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation of a synthetic peptide by purified MAP kinase. (A) A peptide containing residues 64 through 79 of the SAF-1 amino acid sequence is shown. The location of the threonine residue is indicated by an arrow. (B) The SAF peptide was phosphorylated by using 1 U of MAP kinase in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP as described in Materials and Methods. The products were resolved by SDS-14% PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. Lane 1 contained no peptide, and lanes 2 and 3 contained 20 and 50 ng of the peptide, respectively. The migration position of the phosphopeptide is indicated. (C) Phosphoamino acid analysis. The labeled peptide was eluted from an acrylamide gel, hydrolyzed, and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods.

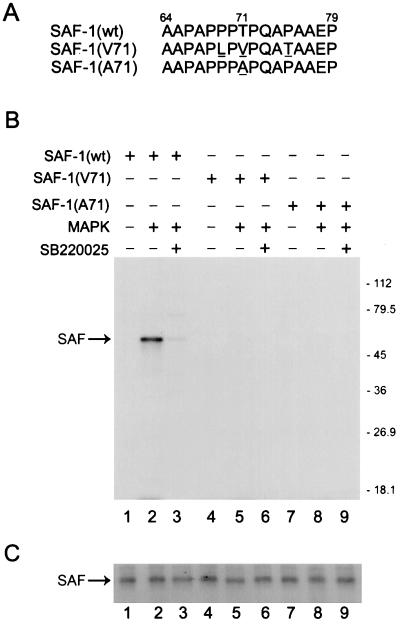

Next, to test whether this motif is functional in the context of the full-length SAF-1 protein, we used bacterium-expressed recombinant SAF-1 protein. We also prepared two full-length mutant SAF-1 proteins that carry mutations at the PPTP site. In the SAF-1(A) mutant, Thr-71 was replaced with alanine, and in the SAF-1(V) mutant, Thr-71 was replaced with valine. In the SAF-1(V) mutant, two other amino acids were also replaced; Pro-69 was changed to a leucine, and Pro-75 was changed to a threonine (Fig. 5A).Bacterium-expressed wild-type SAF-1 and two mutant FLAGSAF-1 proteins were phosphorylated in vitro with MAP kinase and [γ-32P]ATP and further immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 5B). A Western blot assay was done to verify the input and integrity of SAF-1 proteins in each lane (Fig. 5C). While wild-type SAF-1 was phosphorylated by MAP kinase (Fig. 5B, lane 2), both of the mutant proteins remained unphosphorylated (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 8), indicating that mutation of the PPTP region abrogates the ability of MAP kinase to phosphorylate this protein. The specificity of this assay was verified by using SB220025, which inhibited the phosphorylation of the wild-type SAF-1 protein (Fig. 5B, lane 3). This result also indicated that only one MAP kinase phosphorylation site, threonine 71, is present in SAF-1.

FIG. 5.

Mutation of the MAP kinase phosphorylation site of SAF-1. (A) Amino acids 64 to 79 of rabbit SAF-1 are shown. Underlined are amino acid substitutions introduced by site-directed mutagenesis as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Phosphorylation of wild-type (wt) and mutant SAF-1 proteins in vitro. Bacterium-expressed FLAG-SAF1 proteins (100 ng) were incubated with or without 1 U of MAP kinase (MAPK) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min. Some reaction mixtures contained MAP kinase inhibitor SB220025 (200 μM). Following incubation, reaction products were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, separated by SDS-11% PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. The values on the right are molecular sizes in kilodaltons. (C) Western blot analysis. Parallel reactions, as described for panel B, were prepared by using nonradioactive ATP, and the samples were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma). Immunoprecipitated samples were separated by SDS-11% PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with anti-FLAG antibody.

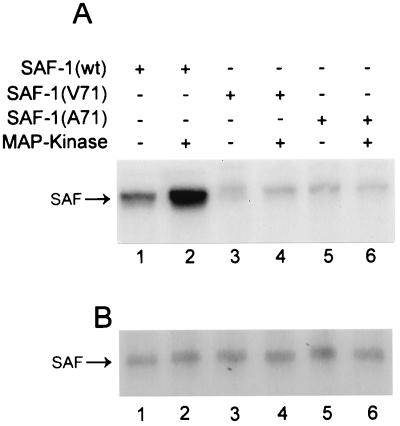

The phosphorylation efficacy of mutant SAF-1 proteins was further tested by an in vivo phosphorylation assay. HIG82 cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing either wild-type or mutant SAF-1 proteins together with a MAP kinase (ERK1) expression plasmid. Following transfection, cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. One-half of these immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6A),and the other half were analyzed by Western blotting to verify the levels of immunoprecipitated SAF-1 proteins (Fig. 6B). Hyperphosphorylation of SAF-1 was noticed due to cotransfection of MAP kinase (compare lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 6A). Both mutant SAF-1 proteins were also phosphorylated (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 5), albeit at a much lower level. The fact that the phosphorylation level of the mutant SAF-1 proteins was not further increased by MAP kinase (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 and 6) indicated that, in vivo, both mutants were effective at resisting MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation. However, this result also showed that SAF-1 contains phosphorylation sites that could be phosphorylated by other protein kinases in the cultured cells, which is consistent with previous observations (39).

FIG. 6.

In vivo phosphorylation of wild-type (wt) and mutant SAF-1 proteins by MAP kinase. (A) HIG82 cells were transfected in duplicate with expression plasmids containing wild-type SAF1 and two mutant plasmids of SAF-1 with or without an expression plasmid containing cDNA of p42 MAP kinase, as indicated. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were metabolically labeled with 32Pi (0.5 mCi/ml) in phosphate-free DMEM for 8 h. 32P-labeled phosphoproteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. One-half of the immunoprecipitated samples were separated by SDS-11% PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) The other half of the immunoprecipitated samples were separated by SDS-11% PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, probed with anti-FLAG antibody, and detected by a chemiluminescence assay.

The transactivation potential of mutant SAF-1 protein is significantly reduced.

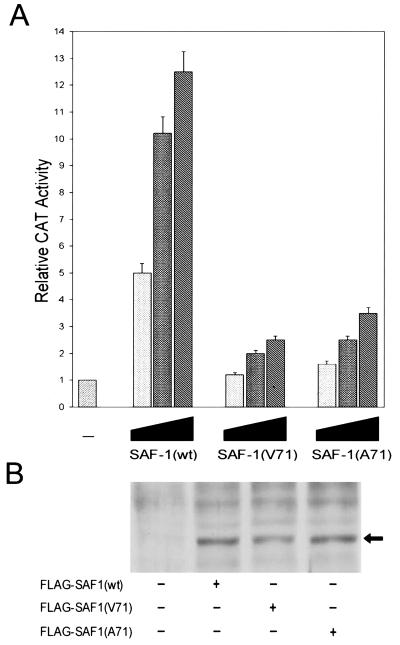

These two mutant SAF-1 proteins allowed us to directly evaluate the role of MAP kinase-mediated signaling in the regulation of SAF-1 activity. The transactivating ability of the two mutant SAF-1 proteins was monitored by cotransfection of HIG82 cells with a SAF-CAT-encoding reporter gene, together with the relevant constructs and IL-1 plus IL-6. Expression of wild-type pCMVFLAG-SAF1 increased reporter gene expression, while both of the mutant forms had a much weaker inducing effect (Fig. 7A).To rule out the possibility that the mutant proteins were not expressed at the same level, we performed a Western immunoblot analysis with an anti-FLAG antibody using some representative transfected cells (Fig. 7B). This experiment showed no discrepancy in the expression of mutant proteins, indicating that MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation of SAF-1 is necessary for proper induction of SAF-1-regulated promoters.

FIG. 7.

Effect of MAP kinase phosphorylation site mutation on SAF-1-regulated promoter. HIG82 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of SAF-CAT reporter plasmid and increasing concentrations of pCMVFLAG-SAF1(wt), pCMVFLAG-SAF1(V71), or pCMVFLAG-SAF1(A71) plasmid DNA, as indicated. The minus sign indicates that cells were transfected with only the SAF-CAT reporter plasmid. Following transfection, cells were incubated with IL-1β (200 U/ml) and IL-6 (500 U/ml). Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, and CAT activity was determined. The results shown are averages of three separate experiments. (B) Western immunoblot analysis of representative cell extracts with anti-FLAG antibody. A Western blot was performed with 50 μg of proteins prepared from transfected cells to determine the relative amounts of each of the FLAG-SAF1 proteins. The arrow indicates the position of the SAF-1 protein expressed in transfected cells.

MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation increases the DNA-binding activity of SAF-1.

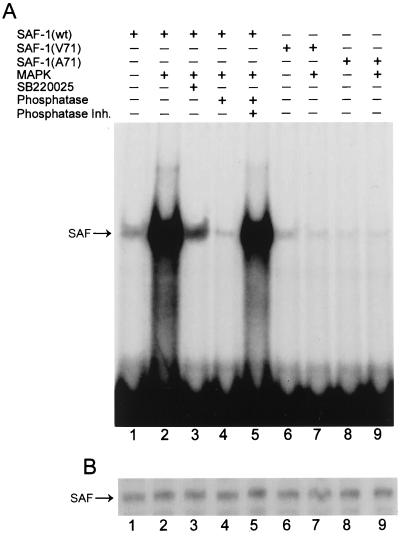

Next, we tested whether the DNA-binding activity of SAF-1 is modulated by its phosphorylation at the MAP kinase recognition site. Bacterium-expressed wild-type and mutant SAF-1 proteins were in vitro phosphorylated by purified MAP kinase and ATP prior to their use in an EMSA with a radiolabeled SAF DNA-binding element (Fig. 8A). The DNA-binding activity of wild-type SAF1 was significantly increased after its phosphorylation with MAP kinase (compare lanes 1 and 2). Addition of SB220025, a potent inhibitor of MAP kinase (lane 3), was highly effective at inhibiting SAF-1 DNA-binding activity. In line with this result, addition of phosphatase severely inhibited the DNA-binding ability of SAF-1 (lane 4), which was blocked by inhibitors of phosphatase (lane 5). Both mutant proteins exhibited lower levels of DNA-binding activity that were comparable to the level obtained with unphosphorylated SAF-1 (lanes 6 and 8). Furthermore, no increase in their DNA-binding ability was seen, even after incubation with MAP kinase (lanes 7 and 9). These results indicated that MAP kinase increases the DNA-binding ability of SAF-1 and that this effect is mediated by the PPTP motif. A Western blot assay with an anti-FLAG antibody was performed to verify the input of SAF-1 proteins in each lane (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Phosphorylation of SAF-1 protein with MAP kinase increases its DNA-binding ability. Bacterium expressed FLAG-SAF1(wt), FLAG-SAF1(A71), and FLAG-SAF1(V71) proteins (0.1 μg) were in vitro phosphorylated with ATP (1 mM) and MAP kinase (1 U) prior to the DNA-binding assay using a radiolabeled SAF DNA-binding element. In some reaction mixtures, as indicated, SB220025 (200 μM), calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (4 U), and phosphatase inhibitors (Inh.; 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 5 μM okadaic acid) were added during in vitro phosphorylation. In lanes 1, 6, and 8, unphosphorylated proteins were used for DNA-binding assays. (B) Western blot analysis. Parallel phosphorylation reactions, as described for panel A, were prepared, and the reaction mixtures were separated by SDS-11% PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma).

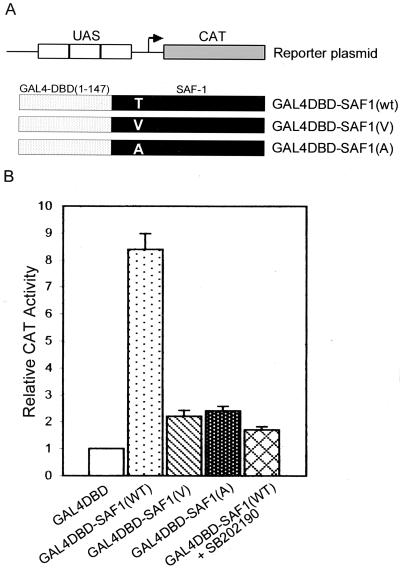

To determine whether MAP kinase directly affects the transactivating potential of SAF-1, we fused, in frame, the full-length SAF-1 cDNA and mutant derivatives SAF1(V) and SAF1(A) downstream of the DNA-binding domain of the yeast GAL4 transcription factor (amino acids 1 to 147). The resulting plasmids, GAL4DBD-SAF1(wt), GAL4DBD-SAF1(V), and GAL4DBD-SAF1(A), were cotransfected into HIG82 cells with a reporter containing three GAL4 DNA-binding (UAS) elements placed in front of a CAT-encoding reporter gene (Fig. 9A). A significant increase in CAT activity was observed when cells were cotransfected with GAL4DBD-SAF1(wt) (Fig. 9B). In contrast, both mutant forms of SAF-1, subcloned in the same vector, displayed poor transactivation of the CAT-encoding reporter. These results suggested that the transactivating ability of SAF-1 is also dependent, at least in part, upon the presence of a MAP kinase site and may require phosphorylation of this site.

FIG. 9.

Transactivating ability of SAF-1 is increased in response to phosphorylation by MAP kinase. (A) Schematic representation of the CAT reporter plasmid containing the GAL4 DNA-binding element, known as the UAS, and three chimeric constructs containing the GAL4 DNA-binding domain, amino acids 1 to 147, fused in frame with the full-length wild-type (wt) SAF-1 protein, amino acids 1 to 477, and two mutant forms containing altered amino acids, valine (V) and alanine (A), at amino acid position 71, which contains threonine (T) in wild-type SAF-1. (B) HIG82 cells were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of the GAL4-CAT reporter gene with or without 0.2 μg of GAL4DBD-SAF1(wt), GAL4DBD-SAF1(A71), or GAL4DBD-SAF1(V71), as indicated. Following transfection, cells were incubated with IL-1β (200 U/ml) and IL-6 (500 U/ml). In some reaction mixtures, SB202190 was added (20 μM). Cells were harvested 48 h after glycerol shock, and CAT activity was determined. The results shown are averages of three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies suggested that the activity of transcription factor SAF-1 is regulated by serine/threonine protein kinases (43-45). In the present report, we provide evidence for the activation of this protein by the MAP kinase signaling pathway. The novel findings are that (i) inhibitors of the MAP kinase signaling pathway block SAF1-regulated promoter induction, (ii) cytokine-mediated stimulation phosphorylates endogenous SAF-1 via the MAP kinase signaling pathway, (iii) MAP kinase directly phosphorylates SAF-1 at a consensus MAP kinase-binding PPTP motif, (iv) phosphorylation of the threonine residue in the PPTP motif of SAF-1 increases its DNA-binding activity, and (v) mutation of the consensus MAP kinase phosphorylation site prevents phosphorylation of SAF-1 and reduces its DNA-binding ability and transactivation potential.

SAF-1 contains one MAP kinase phosphorylation site, PPTP, in the N-terminal region. A similar sequence motif that can be found in the human MAZ and mouse Pur-1 proteins remains uncharacterized. Conservation of this structural motif among these diverse species is indicative of its indispensability. Here, we showed that this site can be phosphorylated by MAP kinase and that mutation of Thr-71, at the core of this motif, reduces the DNA-binding ability and transactivating potential of mutant proteins. In vivo phosphorylation of SAF-1 during IL-1- and IL-6-mediated stimulation of cells was significantly diminished in the presence of inhibitors of MAP kinase (Fig. 3). However, the fact that these inhibitors did not completely block in vivo phosphorylation of SAF-1 indicates that other protein kinases are also involved, albeit at a lower level, in the phosphorylation of SAF-1 during cytokine stimulation of cells. It is interesting that SB203580 and SB202190 are more effective than PD98059 at inhibiting SAF-1 activity. PD98059 is known to be more specific for inhibition of the MEK→ERK signaling pathway (34), while SB203580 and SB202190 are selective in the regulation of the p38 MAP kinase group of proteins (24, 49). Because both groups of inhibitors inhibited SAF-1 function, we believe that SAF-1 can be activated by both the ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways, perhaps at different levels. The significance of the participation of both signaling pathways is not clear, but the possibility of cross talk between these two different pathways cannot be ruled out. Involvement of ERK1/2 and p38 MAK kinase in the regulation of transforming growth factor β-mediated induction of the aggrecan-encoding gene was recently demonstrated (57).

Exactly how MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation enhances the DNA-binding ability and transactivating potential of SAF-1 is still not very clear from the results of this study. The MAP kinase phosphorylation site is present at the N-terminal region of SAF-1, which appears to contain a transactivating domain. This notion is supported by the results presented in Fig. 9. The GAL4 reporter system, which depends on the presence of an activation domain from a heterologous system, showed that MAP kinase phosphorylation site mutation impairs the transactivation potential of SAF-1. However, an increase in the DNA-binding ability of SAF-1 could arise due to the presence of a DNA-binding domain in this region that becomes activated during phosphorylation. It is equally possible that, under normal conditions, SAF-1 remains in such a form that its DNA-binding domain is masked by the N-terminal end. Phosphorylation by MAP kinase at the N-terminal end not only increases its transactivation potential but also unmasks the DNA-binding domain and thereby increases its DNA-binding ability. The exact nature and location(s) of the different domains of SAF-1 have yet to be determined. However, it is tempting to speculate that phosphorylation of threonine 71 changes the configuration of SAF-1 in such a way that not only favors its increased binding to the promoter but also facilitates its interaction with other proteins involved in associating with the basal transcriptional machinery. Incidentally, phosphorylation of CREB by protein kinase A improves its interaction with the components of transcription factor IID (14). It is also possible that phosphorylation increases SAF-1's ability to interact with other transcription factors that might act as a bridge between SAF-1 and the basal transcriptional machinery. Consistent with this possibility, we have seen that interaction of SAF-1 with Sp1 synergistically enhances its transactivation potential (45). Since Sp1 is known to recruit transcription factor IID via its interaction with TAFII130 (33), association of Sp1 with SAF-1 possibly acts as a bridge between SAF-1 and TAFs. Further investigation along this line, which is under way, is necessary for proper understanding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant DK49205 and funds from the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri.

We are grateful to M. Cobb, M. Blanar, and E. Flemington for generous gifts of pCMV-ERK1, pAR(ΔRI)59/60, pRSVGAL4DBD, and GAL4-CAT plasmid DNA samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S. 1997. IL-6 regulated transcription factors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 29:1401-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez E., I. C. Northwood, F. A. Gonzalez, D. A. Latour, A. Seth, C. Abate, T. Curran, and R. J. Davis. 1991. Pro-Leu-Ser/Thr-Pro is a consensus primary sequence for substrate protein phosphorylation. Characterization of the phosphorylation of c-myc and c-jun proteins by an epidermal growth factor receptor threonine 669 protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15277-15285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betts, J. C., J. K. Cheshire, S. Akira, S., T. Kishimoto, and P. Woo. 1993. The role of NF-κB and NF-IL6 transactivating factors in the synergistic activation of human serum amyloid A gene expression by interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. J. Biol. Chem. 268:25624-25631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanar, M. A., and W. J. Rutter. 1992. Interaction cloning: identification of a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that interacts with c-Fos. Science 256:1014-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blenis, J. 1993. Signal transduction via the MAP kinases: proceed at your own RSK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5889-5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossone, S. A., C. Asselin, A. J. Patel, and K. B. Marcu. 1992. MAZ, a zinc finger protein binds to c-myc and C2 gene sequences regulating transcriptional initiation and termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7452-7456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinckerhoff, C. E., T. I. Mitchell, M. J. Karmilowicz, B. Kluve-Beckerman, and M. D. Benson. 1989. Autocrine induction of collagenase by serum amyloid A-like and 2-microglobulin-like proteins. Science 243:655-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb, M. H., and E. J. Goldsmith. 1995. How MAP kinases are regulated. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14843-14846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coetzee, G. A., A. F. Strachan, D. R. van der Westhuyzen, H. C. Hoppe, M. S. Jeenah, and F. C. DeBeer. 1986. Serum amyloid A containing human high density lipoprotein 3: density, size and apolipoprotein composition. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9644-9651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinarello, C. A. 1998. Interleukin-1, interleukin-1 receptors and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Int. Rev. Immunol. 16:457-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan, D. D., A. Stupakoff, S. M. Hedrick, K. B. Marcu, and G. Siu. 1995. A Myc-associated zinc finger protein binding site in one of the four important functional regions in the CD4 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3179-3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edbrooke, M. R., D. W. Burt, J. K. Cheshire, and P. Woo. 1989. Identification of cis-acting sequences responsible for phorbol ester induction of human serum amyloid A gene expression via a nuclear factor κB-like transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:1908-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreri, K., G. Gill, and M. Montminy. 1994. The cAMP-regulated transcription factor CREB interacts with a component of the TFIID complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1210-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flemington, E. K., S. H. Speck, and W. G. Kaelin. 1993. E2F-1-mediated transactivation is inhibited by complex formation with the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6914-6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganapathi, M. K., D. Rzewnicki, D. Samols, S. L. Jiang, and I. Kushner. 1991. Effect of combinations of cytokines and hormones on synthesis of serum amyloid A and C-reactive protein in Hep3B cells. J. Immunol. 147:1261-1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrington, T. P., and G. I. Johnson. 1999. Organization and regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:211-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Her, S., R. A. Bell, A. K. Bloom, B. J. Siddall, and D. L. Wong. 1999. Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase gene expression. Sp1 and Maz potential for tissue-specific expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8698-8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, J. H., and W. S. L. Liao. 1994. Induction of mouse serum amyloid A3 gene by cytokines requires both C/EBP family proteins and a novel constitutive factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4475-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husebekk, A. B., B. Skogen, G. Husby, and G. Marhaug. 1985. Transformation of amyloid precursor SAA to protein-AA and incorporation in amyloid fibrils in vivo. Scand. J. Immunol. 21:283-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh, S., T. Hattri, H. Hayashi, Y. Mizutani, M. Todo, T. Takii, D. Yang, J. C. Lee, S. Matsufuji, Y. Murakami, T. Chiba, and K. Onozaki. 1999. Antiproliferative effect of IL-1 is mediated by p38 MAP kinase in human melanoma cell A375. J. Immunol 162:7434-7440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy, G. C., and W. J. Rutter. 1992. Pur-1, a zinc finger protein that binds to purine rich sequences, transactivates an insulin promoter in heterologous cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:11498-11502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishimoto, T., T. Taga, and S. Akira. 1994. Cytokine signal transduction. Cell 76:253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, J. C., J. T. Laydon, P. C. McDonnell, T. F. Gallagher, S. Kumar, D. Green, D. McNulty, M. J. Blumenthal, J. R. Heys, S. W. Landvatter, J. E. Strickler, M. M. McLaughlin, I. R. Slemens, S. M. Fisher, G. P. Livi, J. R. White, J. L. Adams, and P. R. Young. 1994. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature 372:739-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis, T. S., P. S. Shapiro, and N. G. Ahn. 1998. Signal transduction through MAP kinase cascades. Adv. Cancer Res. 74:49-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, X., and W. S. L. Liao. 1991. Expression of rat serum amyloid A1 gene involves both C/EBP like and NF-κB like transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15192-15201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang, J. S., and J. D. Sipe. 1995. Recombinant human serum amyloid A (apoSAAp) binds cholesterol and modulates cholesterol flux. J. Lipid Res. 36:37-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowell, C. A., R. S. Stearman, and J. F. Morrow. 1986. Transcriptional regulation of serum amyloid A gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 261:8453-8461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luckow, B., and G. Schutz. 1987. CAT constructions with multiple unique restriction sites for the functional analysis of eukaryotic promoters and regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:5490.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackiewicz, A., M. K. Ganapathi, D. Scultz, D. Samols, J. Reese, and I. Kushner. 1988. Regulation of rabbit acute phase protein biosynthesis by monokines. Biochem. J. 253:851-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malle, E., A. Steinmetz, and J. G. Raynes. 1993. Serum amyloid A (SAA): an acute phase protein and apolipoprotein. Atherosclerosis 102:131-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meek, R. L., S. Ureili-Shoval, and E. P. Benditt. 1994. Expression of apolipoprotein serum amyloid A mRNA in human atherosclerotic lesions and cultured vascular cells: implications for serum amyloid A function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3186-3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Näar, A. M., P. A. Beaurang, K. M. Robinson, J. D. Oliner, D. Avizonis, S. Scheek, J. Zwicker, J. T. Kadonaga, and R. Tjian. 1998. Chromatin, TAFs, and a novel multiprotein coactivator are required for synergistic activation by Sp1 and SREBP-1a in vitro. Genes Dev. 12:3020-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang, L., T. Sawada, S. J. Decker, and A. R. Saltiel. 1995. Inhibition of MAP kinase kinase blocks the differentiation of PC-12 induced by nerve growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 270:13585-13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park, J., G. J. Gores, and T. Patel. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide induces cholangiocyte proliferation via an IL-6 mediated activation of p44/p42 MAP kinase. Hepatology 29:1037-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parks, C. L., and T. Shenk. 1996. The serotonin 1A receptor gene contains a TATA less promoter that responds to MAZ and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 271:4417-4430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raingeaud, J. S. Gupta, J. S. Rogers, M. Dickens, J. Han, R. J. Ulevitch, and R. J. Davis. 1995. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J. Biol. Chem. 270:7420-7426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray, A. 2000. A SAF binding site in the promoter region of human γ-fibrinogen gene functions as an IL-6 response element. J. Immunol. 165:3411-3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ray, A., A. P. Fields, and B. K. Ray. 2000. Activation of transcription factor SAF involves its phosphorylation by protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39727-39733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ray, A., M. Hannink, and B. K. Ray. 1995. Concerted participation of NF-κB and C/EBP heteromer in lipopolysaccharide induction of serum amyloid A gene expression in liver. J. Biol. Chem. 270:7365-7374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray, A., and B. K. Ray. 1993. Analysis of the promoter element of serum amyloid A gene and its interaction with constitutive and inducible nuclear factors from rabbit liver. Gene Expr. 3:151-162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray, A., and B. K. Ray. 1994. Serum amyloid A gene expression under acute-phase conditions involves participation of inducible C/EBP-β and C/EBP-δ and their activation by protein phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4324-4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ray, A., and B. K. Ray. 1996. A novel cis-acting element is essential for cytokine-mediated transcriptional induction of the serum amyloid A gene in nonhepatic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1584-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ray, A., and B. K. Ray. 1998. Isolation and functional characterization of cDNA of serum amyloid A-activating factor that binds to the serum amyloid A promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7327-7335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ray, A., H. Schatten, and B. K. Ray. 1999. Activation of Sp1 and its functional co-operation with serum amyloid A-activating sequence binding factor in synoviocyte cells trigger synergistic action of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 in serum amyloid A gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4300-4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ray, B. K., S. Chatterjee, and A. Ray. 1999. Mechanism of minimally modified LDL-mediated induction of serum amyloid A gene in monocyte/macrophage cells. DNA Cell Biol. 18:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ray, B. K., and A. Ray. 1997. Involvement of an SAF-like transcription factor in the activation of serum amyloid A gene in monocyte/macrophage cells by lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry 36:4662-4668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ray, B. K., and A. Ray. 1997. Induction of serum amyloid A (SAA) gene by SAA-activating sequence-binding factor (SAF) in monocyte/macrophage cells. Evidence for a functional synergy between SAF and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28948-28953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saklatvala, J., L. Rawlinson, R. J. Waller, S. Sarsfield, J. C. Lee, L. F. Morton, M. J. Barnes, and R. W. Farndale. 1996. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in platelet aggregation caused by collagen or a thromboxane analogue. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6586-6589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 51.Schlessinger, J. 1994. SH2/SH3 signaling proteins. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sipe, J. D. 1994. Amyloidosis. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 31:325-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strissel, K. J., M. T. Girard, J. A. West-Mays, W. B. Rinehart, J. R. Cook, C. E. Brinckerhoff, and M. E. Fini. 1997. Role of serum amyloid A as an intermediate in the IL1 and PMA-stimulated signaling pathways regulating expression of rabbit fibroblast collagenase. Exp. Cell. Res. 237:275-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taga, T., and T. Kishimoto. 1997. Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:797-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uchida, S., Y. Tanaka, H. Ito, F. Saitoh-Ohara, J. Inazawa, K. K. Yokoyama, S. Sasaki, and F. Marumo. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of the CLC-K1 promoter by myc-associated zinc finger protein and kidney-enriched Krüppel-like factor, a novel zinc finger repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7319-7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uhlar, C. M., and A. S. Whitehead. 1999. Serum amyloid A, the major vertebrate acute-phase reactant. Eur. J. Biochem. 265:501-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe, H., M. P. de Caestecker, and Y. Yamada. 2001. Transcriptional cross-talk between Smad, ERK1/2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways regulates transforming growth factor-β-induced aggrecan gene expression in chondrogenic ATDC5 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14466-14473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]