Abstract

The gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes causes a life-threatening disease known as listeriosis. The mechanism by which L. monocytogenes invades mammalian cells is not fully understood, but the processes involved may provide targets to prevent and treat listeriosis. Here, for the first time, we have identified the insulin-like growth factor II receptor (IGFIIR; also known as the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor CIM6PR or CD222) as a novel receptor for binding and invasion of Listeria species. Random peptide phage display was employed to select a peptide sequence by panning with immobilized L. monocytogenes cells; this peptide sequence corresponds to a sequence within the mannose 6-phosphate binding site of the IGFIIR. All Listeria spp. specifically bound the labeled peptide but not a control peptide, which was demonstrated using fluorescence spectrophotometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Further evidence for binding of the receptor by L. monocytogenes and L. innocua was provided by affinity purification of the bovine IGFIIR from fetal calf serum by use of magnetic beads coated with cell preparations of Listeria spp. as affinity matrices. Adherence to and invasion of mammalian cells by L. monocytogenes was significantly inhibited by both the synthetic peptide and mannose 6-phosphate but not by appropriate controls. These observations indicate a role for the IGFIIR in the adherence and invasion of L. monocytogenes of mammalian cells, perhaps in combination with known mechanisms. Ligation of IGFIIR by L. monocytogenes may be a novel mechanism that contributes to the regulation of infectivity, possibly in combination with other mechanisms.

The gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is a human pathogen that causes listeriosis primarily in immunosuppressed individuals. Symptoms are flu-like, and yet disease may progress to severe complications such as meningitis, septicemia, spontaneous abortion, or listeriosis of the newborn (28, 39, 83). The number of cases of listeriosis range from 40 to 44 per year in Australia (3, 79) and average 100 per year in the United States (13). Although the incidence of listeriosis is low compared to that of other foodborne diseases, the associated mortality rate is high (approximately 30%) (39, 74, 83). Knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying the binding and internalization of Listeria spp. to host cells is limited. New antibiotic, vaccine, and diagnostic targets are needed to prevent and treat infection by Listeria spp., and understanding the processes of adherence and entry into cells is fundamental to defining appropriate preventative and therapeutic strategies.

Random peptide phage display has been successfully employed to identify new receptors and receptor ligands (44, 52, 53, 82) and in epitope mapping and mimicking of protein antigens and antibodies (16, 42, 61) and drug discovery (40, 52, 78). In this study we employed random peptide phage display in an attempt to identify novel surface antigens that may be used as therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers for Listeria spp. and L. monocytogenes. Subtractive panning of the phage display library was performed on immobilized L. monocytogenes cells, and a single peptide sequence was identified. The peptide sequence corresponds to a sequence found in repeat 3 of the insulin-like growth factor II receptor (IGFIIR; also known as the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate [M6P] receptor CIM6PR or CD222), which is one of the binding sites for M6P in this receptor. Phage display results were confirmed by demonstrating that Listeria spp. specifically bound a synthetic peptide (M6Pbs peptide), designed to match the sequence of the M6P binding site, as well as the native receptor. The specificity of the interaction was further investigated by employing competitive binding and invasion assays using the M6Pbs peptide and M6P. We demonstrate a role for this receptor in adherence and invasion of mammalian cells by L. monocytogenes. This is the first time that the IGFIIR has been characterized as a receptor for Listeria spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and cells. (i) Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains used are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains employed in the study

| Species | Serotype or strain | Sourcea | Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes | 1/2a | CDC | Wild type, 1 of 3 strains commonly causing listeriosis |

| 1/2b | TT 1707 | Wild type | |

| 1/2c | CDC | Wild type | |

| 3a | IMVS 0224 | Wild type | |

| 3b | IMVS 0270 | Wild type | |

| 3c | IMVS 1830 | Wild type | |

| 4a | TT 1706 | Wild type | |

| 4b | CDC | Wild type | |

| 4c | ATCC 19116 | Wild type | |

| 4d | ATCC 19117 | Wild type | |

| 4e | ATCC 19118 | Wild type | |

| EGD | K. Iretonb | Wild type | |

| EGD | K. Ireton | Mutant strain lacking inlA | |

| EGD | K. Ireton | Mutant strain lacking inlB | |

| EGD | K. Ireton | Mutant strain lacking inlAB | |

| L. innocua | 4 | IMVS 1871 | Wild type |

| 6a | ATCC 33090 | Wild type, representative serotype | |

| L. ivanovii | 5 | IMVS 1918 | Wild type |

| IMVS 1171 | Wild type | ||

| ATCC 19119 | Wild type | ||

| TECRA food isolate | Wild type | ||

| Bacillus cereus | NDc | TECRA food isolate | Wild type |

| Escherichia coli | ER2738 | NEB | K-12; F′ proA+B+lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 zzf::Tn10(Tetr) fhuA2 glnV Δ(lac-proAB) thi-1 Δ(hsdS-mcrB)5 |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.; TT, Toxin Technology, Sarasota, Fla.; IMVS, Institute for Microbiological and Veterinary Sciences, Adelaide, Australia; NEB, New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.; TECRA, TECRA International, French's Forest, Australia.

University of Toronto, Canada (all strains were from reference 30).

ND, not determined.

(ii) Mammalian cell lines.

MS9 and MS9II cells (L cells) and McCoy cells are mouse fibroblast cell lines. MS9 cells are deficient in IGFIIR expression, while MS9II cells are MS9 cells stably transfected with human IGFIIR, which is expressed by a cytomegalovirus vector (60, 64). Both cell lines were obtained from J. Trapani (Peter MacCallum Cancer Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia) and used with permission of W. Sly (St. Louis University). McCoy cells were sourced from the ATCC.

Preparation of bacterial strains for coating and panning.

Bacterial strains were grown overnight (o/n) (10 ml tryptic soy broth, 37°C, static conditions). An L. monocytogenes cocktail was obtained by combining 100-μl amounts of each serotype (1.1 ml total). An L. innocua cocktail (500 μl of each serotype) and an L. ivanovii cocktail (250 μl of each isolate) were similarly produced (1 ml total). Bacteria were washed four times (10 mM phosphate buffer [pH 8.1], 6,000 × g, 10 min), and the pellets were resuspended (1 ml of phosphate buffer with 0.1% sodium azide).

Preparation of bacterial cells for binding and invasion assays.

Bacterial strains were grown o/n. Log-phase bacterial cultures were obtained by inoculating 0.5 ml of the culture into 9.5 ml of tryptic soy broth. Cultures were grown (37°C with shaking at 200 rpm) to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 to 0.7, washed four times (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 6,000 × g, 10 min), and resuspended (1 ml PBS).

Labeling of bacterial cells.

O/n bacterial cultures were gently washed three times (10 mM phosphate buffer [pH 8.1], 1,400 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and resuspended. Bacteria (1 ml) were labeled by incubating with 5- (and 6-) carboxyfluorescein diacetate-succinimidyl ester (CSFE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) (2 μl, 5 mM, 30 min, 37°C). Bacteria were washed, resuspended (1 ml PBS), and stored at 4°C for up to a week.

Binding of labeled peptides by bacterial cells.

Peptides were synthesized by Auspep Pty. Ltd. (Parkville, Australia) and labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) during synthesis. Peptides were the identified peptide PLAQSGGSSYI (M6Pbs peptide), a control peptide with a randomized sequence of the M6Pbs peptide YPSGSILGSQA (M6Pbs control peptide), and a second control peptide corresponding to the IGFII binding site of the IGFIIR, FGQTRISVGKA (IGFIIbs peptide) (27). Lyophilized peptides were resuspended (5 mg/ml) with 50% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (M6Pbs peptide and M6Pbs control peptide) or PBS (IGFIIbs peptide). Bacterial cultures were washed (1 ml PBS) and resuspended with each of the peptides (40 μl, 2 h, 4°C). Bacteria were washed, resuspended (1 ml PBS-0.1% sodium azide), and stored at 4°C for up to a week.

Preparation of mammalian cells for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and invasion assays.

MS9, MS9II, and McCoy cells were grown in serum-free supplemented Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing fetal calf serum (FCS; CSL, Parkville, Australia) (10%), HEPES (25 mM), l-glutamate (2 mM), sodium pyruvate (0.1g/liter), and penicillin-streptomycin (100 μg/ml). To maintain IGFIIR expression, MS9II cell medium contained methotrexate (SIGMA, Sydney, Australia) (3.2 μM). For invasion assays, cells were seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates (∼105 cells/well) and grown until >90% confluent.

Phage display.

Phage displays were produced using a Ph.D. 12mer random phage display peptide library (NEB, Beverly, Massachusetts). Panning was performed using Dynex Immunolon microtiter wells coated with L. monocytogenes cocktail (150 μl/well, diluted 1:100, in phosphate buffer, o/n, room temperature [RT]). After coating, wells were blocked (5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA], 300 μl/well, 2 h, RT), washed once (distilled water), and stored at 4°C until further use. Nonspecific phages were removed by absorbing the phage library sequentially on uncoated wells and wells coated with BSA (1 mg/ml, 30 min, RT, rocking). Selection of antigen-positive phages was performed by the addition of the absorbed phage library to immobilized L. monocytogenes cocktail (60 min, RT, rocking). Unbound phages were discarded, and wells were washed three times (Tris-buffered saline-0.5% Tween 20). Subtractive selection was carried out by the sequential application of L. innocua cocktail and L. ivanovii cocktail (100 μl, 1:1,000 in Tris-buffered saline) to wells (30 min, RT), with washing between steps. Low-affinity L. monocytogenes-specific phage peptides were removed by rapid exposure and removal of L. monocytogenes cocktail (100 μl). The wells were washed before incubation with L. monocytogenes cocktail (30 min, RT) to elute specific high-affinity bound phages. The phage eluate was titered, amplified, and panned twice more according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was prepared from single phage clones after two rounds of panning by phenol extraction (Tris-buffered phenol, 1:1) and ethanol precipitation before DNA sequencing (Newcastle Sequencing, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia).

Binding assays using fluorescently labeled peptides.

Microtiter wells were coated with bacterial preparations (1:100) and BSA (1 mg/ml, 150 μl/well, in phosphate buffer). M6Pbs peptide and M6Pbs control peptide were serially diluted (100 to 6.25 μg/ml) in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBS/T) containing 25% DMSO,while the IGFIIbs peptide was serially diluted in PBS/T. Binding was performed by incubating peptides with immobilized bacteria (100 μl/well, o/n, 4°C). Wells were washed five times (PBS/T), and distilled water (100 μl) was added before the fluorescence was read (excitation 485 nm, emission 538 nm) using a fluorescence enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader (Fluoromark; Bio-Rad).

Affinity purification of IGFIIR from FCS by use of magnetic beads coated with bacteria.

Magnetic beads (Dynal, Victoria, Australia) (0.5 ml) were prepared as described in the manufacturer's instructions, coated with L. monocytogenes cocktail (1 ml, 1:100, 0.1 M phosphate buffer [pH 8.0], o/n, 4°C, rotating wheel) and washed five times (50 ml PBS) to remove unbound material. For coating of beads with cell surface protein extract, an o/n culture of L. monocytogenes (250 ml) was washed twice (50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.6], 1,400 × g, 4°C), resuspended (3 ml, 50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.6], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]), and incubated in a water bath (2 h, 70°C). Cell debris was removed (3,000 × g, 10 min), the cell surface protein extract was dialyzed (50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.6], o/n, 4°C), and magnetic beads were coated with the extract (1:100). Affinity purification of IGFIIR was performed by incubating coated beads with FCS (250 ml, o/n, RT, rotating wheel). Unbound material was removed by washing three times (50 ml PBS, 4°C), and bound material was eluted (1 ml, 0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5). Eluates were concentrated using microcon concentrators (molecular weight, 30,000; Millipore), and concentrates were made up to 0.25 ml (10 mM Tris-0.8% NaCl, pH 8.0) and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting.

Preparation of mammalian cells for protein analysis.

Mammalian cells were harvested (10 ml, PBS-0.05% Triton X-100) and sonicated (10,000 Hz, 2 min), and the protein content of cell lysates was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentrations of cell lysates were adjusted (0.5 mg/ml) prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE (47) was performed using 10%- or 4- to 20%-gradient polyacrylamide gels (Gradipore, French's Forest, Australia). Briefly, samples were heated in sample buffer and separated on gels, and proteins were visualized using Coomassie blue or a silver staining kit (Bio-Rad, Sydney, Australia). For Western blotting, gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer (12 mM Tris, 0.96 M glycine [pH 8.0], 20% methanol), and transfer was performed (o/n, 4°C, 60 V). The membrane was blocked (5% skim milk powder-PBS/T, 4 h, RT), and bovine IGFIIR was detected with monoclonal mouse anti-bovine IGFIIR antibody (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO) (1 μg/ml, 1% skim milk-PBS/T) as primary antibody (o/n, RT) and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G horseradish peroxidase conjugate (SIGMA) (1:5,000, 1% skim milk-PBS/T) as secondary antibody (1.5 h, RT). Detection of human or murine IGFIIR was performed with goat polyclonal anti-human or anti-mouse IGFIIR, respectively (Affinity BioReagents) (1 μg/ml, 1% skim milk-PBS/T) and rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G horseradish peroxidase conjugate (SIGMA, 1:100,000, 1% skim milk-PBS/T). Blots were washed three times between steps (5 min, PBS/T, rocking). Bands were detected using Supersignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

FACS scanning.

Fluorescent cells were detected with a FACScan flow cytometer and analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Bacterial binding was calculated by determining the relative fluorescent intensity (relative fluorescent intensity = geographical mean of the sample/geographical mean of the control).

Binding of FITC-labeled peptides by bacteria.

FITC peptide-labeled bacteria (100 μl) were taken up in paraformaldehyde (900 μl, 1%), and control procedures were performed by incubating bacterial cells in 25% DMSO-PBS (as the control for the FITC-M6Pbs peptide and FITC-M6Pbs control peptide) or PBS (FITC-IGFIIbs peptide).

Effect of M6Pbs peptide on bacterial adherence.

CSFE-labeled bacteria (50 μl, 109 to 1010 cells/ml) were incubated with M6Pbs peptide (40 μl, 5 mg/ml, 30 min, 37°C) or the control (25% DMSO in PBS). Unbound peptide was removed by washing three times (5 min, PBS, 6,000 × g), and bacteria were incubated with mammalian cells (400 μl, 106 to 107cells/ml, DMEM, 20 min, 37°C). Samples were washed three times (5 min, PBS, 700 × g) and resuspended (200 μl, 2% paraformaldehyde).

Effect of M6P on bacterial adherence.

CSFE-labeled bacteria (50 μl, 109 to 1010cells/ml) and mammalian cells (50 μl of 106 to 107cells/ml) were added to 400 μl of PBS, PBS containing 50 mM glucose-6 phosphate (G6P) (controls), or PBS containing 0, 10, 20, or 50 mM M6P (20 min, 37°C). Samples were washed three times with PBS, PBS containing 10 mM G6P (control samples), or PBS containing 10 mM M6P (M6P samples) (5 min, 700 × g) and resuspended (200 μl, 2% paraformaldehyde).

Invasion assay-gentamicin protection assay.

Mammalian cell monolayers were washed three times (DMEM, 37°C) before the addition of log-phase bacterial cells at a multiplicity of infection of ∼10:1 (1 h, 37°C) followed by the addition of gentamicin (20 μg/ml final concentration, 2 h, 37°C). Mammalian cells were washed three times (serum-free DMEM, 37°C), and cells were lysed by the addition of ice-cold 0.2% Triton X-100 (15 min, 4°C). Intracellular bacterial cells were recovered by scraping the wells vigorously and plating recovered bacteria (tryptic soy agar plates, o/n, 37°C). Bacterial colonies were counted, and the percentage of relative invasion was determined using the following equation: number of recovered bacteria × 100%/number of bacteria in inoculum.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis of statistical significance for studies showing dose-dependent variations (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 6 and 8) was performed using the test Nptrend (23). The two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed to determine statistical significance of differences observed between two groups (Fig. 1 and 2; see also Fig. 5 and 7).

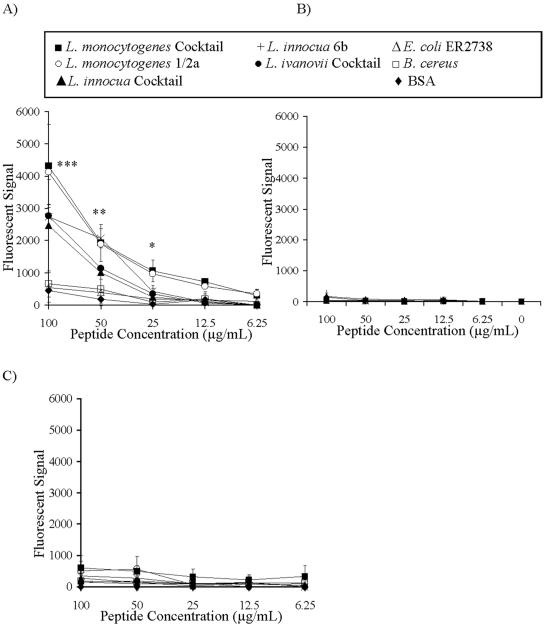

FIG. 1.

Binding of FITC-labeled M6Pbs peptide to immobilized bacteria. Bacterial preparations were immobilized on microtiter wells, and binding of synthetic, FITC-labeled peptides was determined by measurement of fluorescence spectrophotometry. (A) Binding of the M6Pbs peptide by various Listeria spp. was dose dependent (P < 0.01) and was significantly increased compared to control results at 100 μg/ml (***, P < 0.001), 50 μg/ml (**, P < 0.01), and 25 μg/ml (*, P < 0.05). (B and C) Only background binding of the M6Pbs-control peptide (B) and control IGFIIRbs peptide (corresponding to a sequence within the IGFII binding site of the IGFIIR) (C) by immobilized bacterial preparations and BSA was observed in comparisons to binding of the M6Pbs peptide at 100 μg/ml (***, P < 0.001), 50 μg/ml (**, P < 0.01), and 25 μg/ml (*, P < 0.05). Data presented are means ± standard deviations (n = 3 in duplicate).

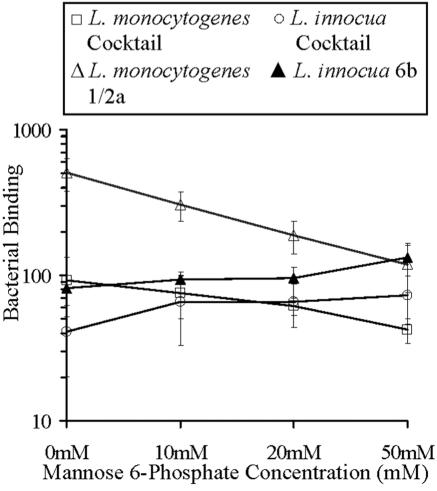

FIG. 6.

The effect of M6P on binding of Listeria spp. to McCoy cells. CSFE-labeled Listeria spp. were incubated with McCoy cells in the presence of M6P (0 to 50 mM), and binding was measured by FACS. Bacterial binding was determined by calculating the relative fluorescent intensity. Significant dose-dependent inhibition of binding was observed for L. monocytogenes cocktail (P < 0.05) and serotype 1/2a (P < 0.01). There was a smaller but significant dose-dependent increase in binding for L. innocua cocktail and serotype 6b (P < 0.05). Data presented are means ± standard deviations (n = 3 in duplicate).

FIG. 8.

The effect of M6P on invasion of Listeria spp. into McCoy cells. Invasion assays of Listeria spp. into McCoy cells were performed in the presence of M6P (0 to 50 mM). Significant inhibition of invasion of McCoy cells by L. monocytogenes cocktail (P < 0.01) and serotype 1/2a (P < 0.01) and increases in invasion by L. innocua cocktail (P < 0.01) and serotype 6b (P < 0.01) were observed. Data presented are means ± standard deviations (n = 3 in duplicate).

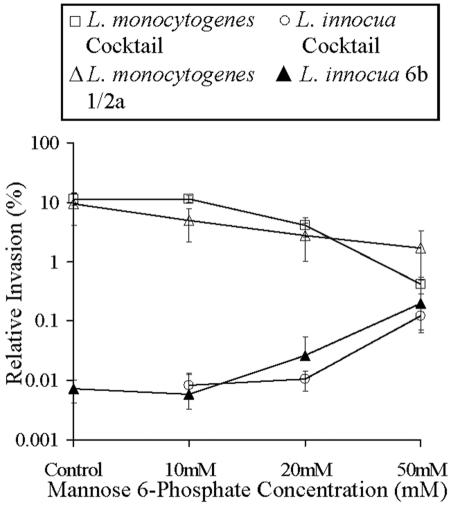

FIG. 2.

Binding of FITC-labeled M6Pbs peptide by various bacterial strains. Binding of FITC-labeled peptides to Listeria spp. and controls was measured by FACS, and relative fluorescent intensity was calculated. (A) Levels of binding of the M6Pbs peptide by various Listeria spp. were significantly (**, P < 0.01) elevated compared to control (E. coli and B. cereus) results. (B) Binding of the M6Pbs-control peptide and IGFIIbs peptide (controls) by cocktails of L. monocytogenes (**, P < 0.01), L. innocua (*, P < 0.05), and L. ivanovii (**, P < 0.01) was significantly lower than binding of the M6Pbs peptide. Data presented are means ± standard deviations (n = 2 in duplicate).

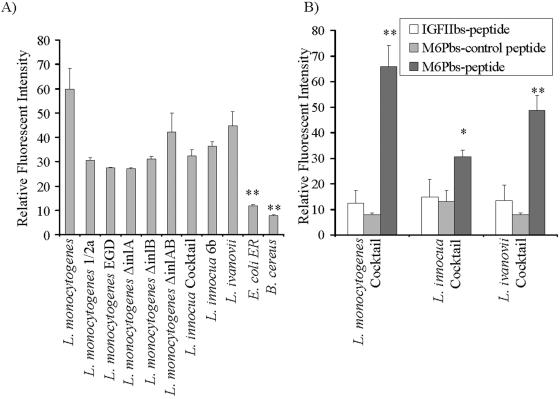

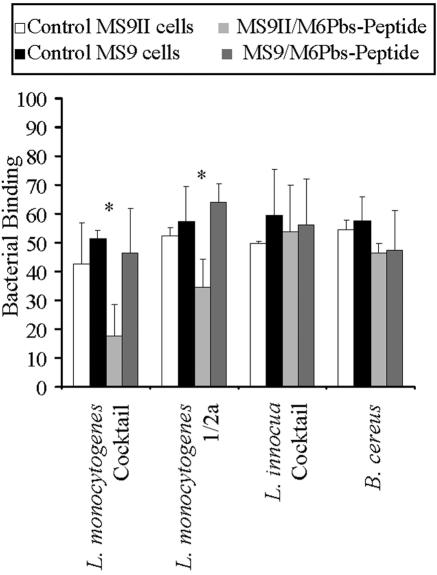

FIG. 5.

Binding of Listeria spp. to MS9 and MS9II cells in the presence of M6Pbs peptide by FACS. Bacteria were labeled with CFSE and incubated with MS9 and MS9II cells. Bacterial binding was determined using FACS by calculating the relative fluorescent intensity. No differences were observed between binding to MS9II cells and binding to MS9 cells for any of the bacterial strains used. Binding was further investigated using inhibition of binding by the M6Pbs peptide. M6Pbs peptide was bound by CSFE-labeled bacteria, which were then incubated with MS9 and MS9II cells. Significant inhibition of binding to MS9II cells in the presence, compared to the absence, of the M6Pbs peptide was observed for L. monocytogenes cocktail (*, P < 0.01) and serotype 1/2a (**, P < 0.05) but not L. innocua cocktail or B. cereus. Data presented are means ± standard deviations (n = 2 in duplicate).

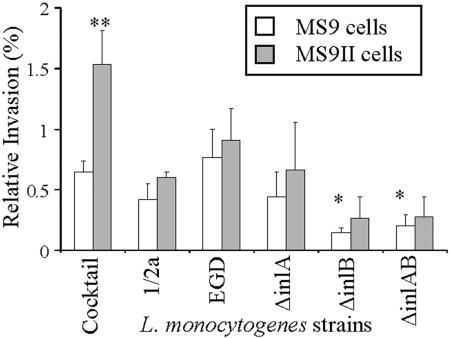

FIG. 7.

Invasion of Listeria spp. into MS9 and MS9II cells. Log-phase cultures of L. monocytogenes at a multiplicity of infection of 10:1 were incubated with MS9 and MS9II cells, and gentamicin was added to kill extracellular bacteria. Intracellular listerial cells were released by lysis of mammalian cells and recovered by plating onto media. Invasion was further investigated using listerial strains deficient in known virulence factors InlA and/or InlB. Percent relative invasion was calculated using the number of recovered listerial cells × 100%/the number of cells in the inoculum. Invasion of L. monocytogenes cocktail was significantly (**, P < 0.01) increased in MS9II cells compared to MS9 cell results. Invasion of L. monocytogenes strains lacking InlB was significantly reduced compared to the wt EGD strain results (*, P < 0.05). Noninvasive L. innocua was used as a control and was not recovered from lysed mammalian cells (not shown). Data presented are means ± standard deviations (n = 3 in duplicate).

RESULTS

Identification of a peptide bound specifically by Listeria spp. by phage display.

A random peptide phage display was used to identify novel surface antigens on cells of Listeria spp. A 12mer phage display library was used in a protocol designed to select peptides on phages that were bound specifically and with high affinity by a cocktail of L. monocytogenes serotypes. Decreasing ratios of phage input/phage recovery indicated that enrichment of antigen-positive phage peptides occurred after each round of panning (Table 2). DNA from 10 single plaques was prepared and sequenced after the second round of panning. The amino acid sequence deduced for 9 of the 10 clones was TTSPLSQGSSYI. The NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/entrez/query.fcgi?db = Protein) was screened to show that the identified peptide had significant homology (underlined amino acids) with the peptide sequence PL(A)Q(S)(G)GSSYI found in the human IGFIIR (59) (NCBI accession no. 225752).

TABLE 2.

Panning of phage-displayed peptidesa

| Panning round | Phage input (PFU) | Phage recovery (PFU) | Input/recovery ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 × 1011 | 2.5 × 105 | 4 × 105 |

| 2 | 1.3 × 109 | 3 × 105 | 4.3 × 103 |

| 3 | 1.3 × 1011 | 3 × 108 | 4.3 × 102 |

Panning was performed by incubating the 12mer peptide phage display library with immobilized L. monocytogenes cells from a cocktail of different serotypes. Phage input (number of phages for each pann) and phage recovery (number of phages after elution) were measured by phage titration, and the ratio of phage input to phage recovery was determined.

The synthetic peptide is bound by Listeria spp.

Binding of the labeled synthetic M6Pbs peptide by Listeria spp. was confirmed by fluorescence spectrophotometry and FACS.

Binding of labeled peptides by immobilized bacterial cells.

The identified peptide was synthesized, labeled with FITC (FITC-M6Pbs peptide), and used in binding assays to show that listerial cells specifically bound the peptide. The identified peptide was bound by all Listeria spp. but not by other bacterial species (such as the gram-positive species Bacillus cereus and the gram-negative strain Escherichia coli ER2738) or by BSA (for 100 μg/ml, P < 0.001; for 50 μg/ml, P < 0.01; and for 25 μg/ml, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). To further demonstrate the specific association between the M6Pbs peptide, Listeria cells, and the IGFIIR, two FITC-labeled control peptides were used in this study. One of the control peptides (M6Pbs-control peptide) had a randomized sequence of the M6Pbs peptide (YPSGSILGSQA), and a second peptide (FITC-IGFIIbs peptide) corresponded to a sequence within the IGFII binding site of the IGFIIR (FGQTRISVGKA) (10). By contrast to the M6Pbs peptide results, neither of the control peptides were bound by Listeria spp. or other bacteria (for 100 μg/ml, P < 0.001; for 50 μg/ml, P < 0.01; and for 25 μg/ml, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B and C).

Analysis of binding of labeled peptides by bacterial cells.

Specific binding of the FITC-M6Pbs peptide by Listeria spp. was confirmed by FACS. All Listeria spp. bound this peptide at significantly higher levels than controls (P < 0.01). L. monocytogenes deficient in virulence factor InlA and/or InlB bound the M6Pbs peptide at levels similar to those seen with wild-type (wt) strains, demonstrating that loss of these virulence factors had no impact on the binding of this peptide. M6Pbs peptide did not bind to controls (B. cereus and E. coli ER2783) (Fig. 2A). To further determine that the binding of FITC-M6Pbs peptide by Listeria spp. was specific, binding of the FITC-labeled control peptides (M6Pbs-control peptide and IGFIIbs peptide) by cocktails of L. monocytogenes, L. innocua, and L. ivanovii serotypes was measured and compared to FITC-M6Pbs peptide binding by use of the same preparations. Binding of FITC-labeled control peptides by cocktails of L. monocytogenes, L. innocua, and L. ivanovii serotypes was significantly reduced compared to binding of FITC-M6Pbs peptide (P < 0.001, P < 0.05, and P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2B).

Listeria spp. can bind the native receptor.

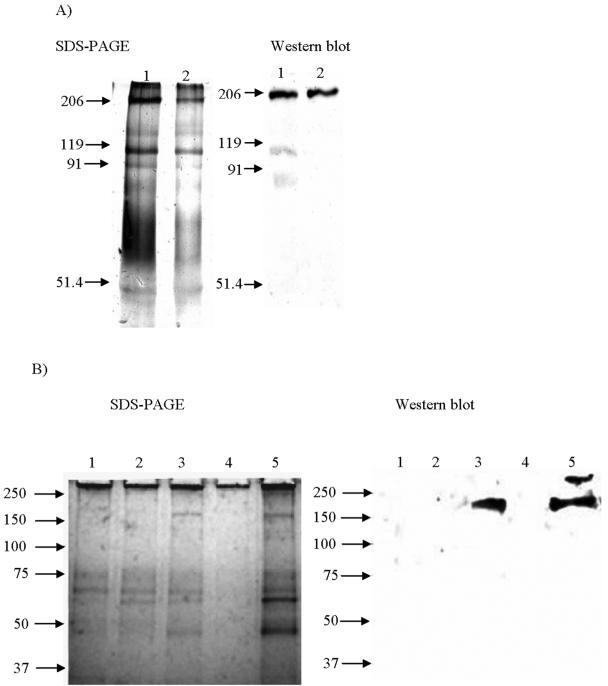

To confirm that Listeria spp. can bind the native IGFIIR, whole bacterial cells and surface protein extracts were coated onto magnetic beads and used to isolate the native receptor from FCS by affinity purification. Purified IGFIIR protein is not commercially available; however, a truncated form missing the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor is circulating in fetal serum and can be affinity purified from FCS by use of M6P affinity matrices (11, 49, 50). Although the M6Pbs peptide sequence used is homologous to that of the human IGFIIR, demonstration of binding of the bovine IGFIIR by Listeria spp. is relevant because this protein is highly conserved in mammalian species (38, 84). The IGFIIR was eluted from listerial preparations and detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using a monoclonal anti-bovine IGFIIR antibody. A strong band of approximately 200 kDa, corresponding to the molecular mass reported for the circulating form of the receptor (49), was detected in affinity-purified material from L. monocytogenes and L. innocua preparations but not in materials purified from L. ivanovii or controls (Fig. 3). There were also some additional faint (119 kDa and below) bands detected in the Western blot (Fig. 3A) that may have resulted from the detection of breakdown products of the IGFIIR.

FIG. 3.

Affinity purification of bovine IGFIIR by use of magnetic beads coated with various bacterial preparations. Magnetic beads were coated with bacterial preparations and incubated with FCS. Affinity-purified material was eluted, and binding of IGFRII was detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The Western blot was developed using a specific monoclonal anti-bovine IGFIIR antibody. Bovine IGFIIR (∼200 kDa) was bound by L. monocytogenes cocktail cells (panel A, lane 1) and cell surface proteins (panel A, lane 2) and cells of L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2a (panel B, lane 5) and L. innocua cocktail (panel B, lane 3) but not by cells of L. ivanovii cocktail (panel B, lane 4) or controls (E. coli ER2738 [panel B, lane 1] or B. cereus [panel B, lane 2]). Standard molecular masses are represented in kilodaltons. The gels depicted are representative of duplicate experiments.

The IGFIIR is involved in binding of Listeria spp. to mammalian cells.

A role for the IGFIIR in binding of Listeria spp. to mammalian cells was demonstrated. The receptor was shown to be present on MS9II and McCoy cells. Binding of Listeria spp. to these cells was inhibited by the M6Pbs peptide and the M6P.

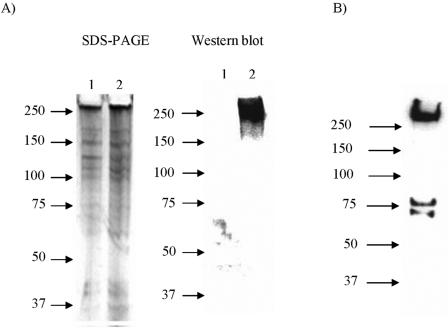

Detection of the IGFIIR in mammalian cells.

The presence of the IGFIIR in MS9II and McCoy cells but not in MS9 cells was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using antibodies against human or murine IGFIIR. A distinct band of approximately 300 kDa was detected in Western blots of cell lysates prepared from MS9II and McCoy cells but not in MS9 cells (Fig. 4). The detected band (300 kDa) corresponds to the reported molecular mass for this receptor in mammalian cells (84). Additional smaller-sized bands (75 kDa and below), which may have been due to breakdown products of the IGFIIR specifically interacting with the antibodies, were also detected.

FIG. 4.

Detection of IGFIIR in MS9, MS9II, and McCoy cells. Cell lysates of MS9, MS9II, and McCoy cells were prepared by sonication and separated on a 4- to 20%-gradient SDS-PAGE gel prior to Western blotting. The Western blots were developed using a monoclonal anti-human IGFIIR antibody for MS9 and MS9II cells and a polyclonal anti-mouse IGFIIR antibody for McCoy cells. The IGFIIR (∼300 kDa) was detected in cell lysates from MS9II (panel A, lane 2) and McCoy (panel B, lane 1) cells but not MS9 (panel A, lane 1) cells. Standard molecular masses are represented in kilodaltons. The gels depicted are representative of duplicate experiments.

Binding of Listeria spp. to mammalian cells in the presence of M6Pbs peptide.

MS9 and MS9II cells were used to demonstrate that binding of Listeria spp. to the IGFIIR can be inhibited by the M6Pbs peptide. CSFE-labeled L. monocytogenes (cocktail and serotype 1/2a), L. innocua (cocktail), and B. cereus were incubated with M6Pbs peptide. Binding to MS9 and MS9II cells with or without prior incubation with the peptide was examined by FACS. There were no differences in binding of any of the bacterial strains to MS9 compared to MS9II cell results in the absence of peptide (Fig. 5). However, binding of L. monocytogenes (cocktail and serotype 1/2a) to MS9II cells was significantly inhibited by M6Pbs peptide (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) but no inhibition was observed for L. innocua (cocktail) or B. cereus (control). The M6Pbs peptide did not inhibit binding of any of the bacterial preparations to MS9 cells (Fig. 5).

Binding of bacterial preparations to mammalian cells in the presence of soluble M6P.

The peptide sequence identified by phage display is located in repeat 3 of the IGFIIR, which has been identified as a carbohydrate binding site with specificity for M6P (11, 37). Binding of L. monocytogenes to McCoy cells was inhibited using soluble M6P as a competitive inhibitor. CSFE-labeled listerial preparations were incubated with mammalian cells, and adherence was measured by FACS (Fig. 6). Binding of L. monocytogenes (cocktail and serotype 1/2a) to McCoy fibroblast cells was significantly inhibited by M6P in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). Surprisingly, adherence of L. innocua (cocktail and serotype 6b) to McCoy cells increased significantly in the presence of M6P (P < 0.05). To determine that inhibition was a result of M6P specifically inhibiting binding of Listeria spp. to the M6P binding sites of the IGFIIR, G6P was used as an inhibitor in control experiments. G6P is a closely related analogue of M6P, but it has no affinity for the M6P binding sites of the IGFIIR. Binding of Listeria spp. to McCoy cells was not inhibited in the presence of G6P (results not shown).

The IGFIIR is involved in invasion of mammalian cells by Listeria spp.

A role for the IGFIIR in invasion of mammalian cells by Listeria spp. was demonstrated. Invasion of L. monocytogenes into MS9II cells was significantly increased compared with invasion of MS9 cells. Furthermore, invasion of McCoy cells by L. monocytogenes was significantly inhibited by soluble M6P.

Invasion of Listeria spp. into MS9 and MS9II cells.

Invasion of wt L. monocytogenes (cocktail, serotype 1/2a, or strain EGD) into MS9/MS9II cells represented approximately 1% of the inoculum, but invasion was significantly (0.2 to 0.3%) reduced in strains lacking InlB (P < 0.05) compared to wt strain results (cocktail, serotype 1/2a, and strain EGD) (Fig. 7). Invasion of L. monocytogenes cocktail into MS9II cells was significantly greater than MS9 cell invasion, as determined using raw (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7) or normalized (P < 0.01) (not shown) data. Normalizing data is an accepted method of analyzing data (76). Results of invasion of L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2a and strain EGD and strains lacking inlA, inlB, and inlAB into MS9II cells compared to MS9 cell invasion were not significantly different, as determined using raw data (Fig. 7). However, significantly greater invasion into MS9II cells compared to MS9 cell invasion for L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2a (P < 0.05) and strains lacking inlA (P < 0.01), inlB (P < 0.05), and inlAB (P < 0.05) was determined by normalizing raw data (not shown). Normalized relative invasion values were obtained by setting relative values for invasion into MS9 cells at 1%, and relative invasion into MS9II cells was calculated relative to 1%. The noninvasive species L. innocua was used as a control and did not invade MS9 or MS9II cells (not shown).

Invasion of Listeria spp. into McCoy cells in the presence of soluble M6P.

Invasion studies were performed by incubating log-phase listerial cultures with McCoy cells in the presence of various concentrations of M6P as a competitive inhibitor. Invasion of McCoy cells by L. monocytogenes (cocktail and serotype 1/2a) was inhibited by M6P in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.01). Inhibition of entry occurred at a concentration of 10 mM M6P (relative invasion reduced from 9.5% to 5%) but was most prominent at 50 mM (relative invasion reduced to 1.7%) (Fig. 8). Invasion of McCoy cells by L. innocua cocktail and serotype 6b significantly increased in the presence of M6P in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8).

DISCUSSION

In this investigation we demonstrated for the first time that Listeria spp. utilize the IGFIIR on mammalian cells during binding and invasion. Random peptide phage display was first used to identify binding of a peptide by L. monocytogenes with high affinity, and this peptide corresponds to a M6P binding site on the IGFIIR. Specific binding of the synthetically produced labeled peptide was confirmed and was independent of known virulence factors (InlA and InlB) (Fig. 1 and 2). L. monocytogenes and L. innocua (but not L. ivanovii or controls) also bound the native receptor protein (Fig. 3). A role for the receptor in binding and invasion of L. monocytogenes and L. innocua was demonstrated by competitive inhibition with the peptide and soluble M6P and by using mammalian cells transfected with the IGFIIR (Fig. 4 to 8).

Thus, all Listeria spp. bind the M6Pbs peptide; however, some differences were observed in the binding of the IGFIIR protein from different mammalian species by some Listeria spp. L. ivanovii bound the M6Pbs peptide (corresponding to the human IGFIIR sequence) (Fig. 2) but not the native bovine IGFIIR (Fig. 1 and 3).

The functions of the IGFIIR in mammalian cells are to bind and internalize insulin-like growth factor II (IGFII) (26, 36, 43, 75), to internalize and to sort lysosomal enzymes and other M6P-tagged proteins (11, 12, 24, 45, 46), and to regulate transforming growth factor β activity (33, 51). The majority of the receptor is found inside the cell, with only 5 to 10% located on the cell surface (45). The surface-associated IGFIIR is an important factor in the regulation of cell growth and in tumor suppression, because it removes IGFII from circulation and regulates transforming growth factor β activity (27).

The IGFIIR is made up of 15 cysteine-based repeats, a transmembrane domain, and a short, hydrophobic cytoplasmic domain (59). The peptide sequence identified in our studies is located in repeat 3 of the extracellular domain that is one of the three M6P binding sites of the IGFIIR (25, 68). Recently, the amino acid sequence in repeat 3 was determined (25, 38, 65); the identified (M6Pbs) sequence is located between two conserved cysteine residues (C334 and C375) and upstream of a conserved residue (Y368) which is essential for carbohydrate recognition (38, 65, 68, 84).

Adherence of Listeria to mammalian cells is known to occur through a wide range of different listerial virulence factors and cell surface components such as fibronectin binding proteins (31, 41), carbohydrates (15, 20, 22, 67), protein 60 (9, 72), the autolysin ami (58), lipoproteins (69), and teichoic and lipoteichoic acids (1, 34, 66, 67). These listerial cell surface components interact with a diverse range of host cell receptors, many of which have not yet been identified. Our results demonstrate that the IGFIIR is another such host cell receptor for Listeria spp. that is involved in both binding and invasion.

Binding of L. monocytogenes, but not L. innocua, to the receptor on MS9II cells could be competitively inhibited by the M6Pbs peptide but not the control peptides (M6Pbs-control peptide and IGFIIbs peptide). Furthermore, binding of L. monocytogenes to McCoy cells was significantly inhibited by M6P in a dose-dependent manner. Competitive inhibition studies using soluble M6P as an inhibitor of binding of other ligands are established techniques for the investigation of IGFIIR function (37, 62, 73). The M6P effects were specific, because G6P, a closely related analogue that does not bind to the IGFIIR (38), had no effect. These results demonstrate that the IGFIIR is involved in adherence of L. monocytogenes. Surprisingly, adherence of L. innocua strains to McCoy cells increased significantly in the presence of M6P. When considered together, these results suggest that the usage of the IGFIIR differs between different Listeria spp.

A fundamental role for the IGFIIR in invasion of L. monocytogenes is also evident by the demonstration that there was a trend to increased invasion into MS9II cells compared to MS9 cell invasion for all L. monocytogenes serotypes and mutants tested. Furthermore, invasion of McCoy cells by L. monocytogenes strains was significantly inhibited by M6P in a dose-dependent manner. Internalization of L. monocytogenes by mammalian cells is known to be mediated by the major virulence factors InlA and InlB through their interaction with specific host cells receptors E-cadherin and the hepatocyte growth factor receptor, respectively (17, 18, 56, 57). However, invasion into mouse fibroblast cells is not mediated by InlA, because the murine E-cadherin contains an amino acid substitution that abolishes interaction with InlA (48). L. monocytogenes strains deficient in InlA invaded MS9 and MS9II at approximately the same level as wt strains, confirming that invasion into murine cells is not mediated by InlA (48). Invasion of MS9II and MS9 cells by L. monocytogenes bacteria deficient in InlB and both InlA and InlB was significantly reduced.

Both of these observations indicate that internalization into murine fibroblast cells is primarily mediated by InlB (8, 19). The observation that invasion into MS9 cells by mutants lacking inlB and inlAB was not completely abolished also indicates that yet other receptors may be involved. The residual invasiveness of L. monocytogenes mutants lacking the major virulence factors InlA and InlB was also evident in other studies (4, 7, 29, 35) and suggests that there are a number of other host cell receptors involved in L. monocytogenes invasion (2, 34).

A significant increase in both binding and invasion of L. innocua of murine fibroblast cells was observed in the presence of soluble M6P in a dose-dependent manner. A possible explanation for this observation is that, in contrast to pathogenic L. monocytogenes, the nonpathogenic species L. innocua cannot utilize hexose phosphate sugars (14, 70, 77). We speculate, therefore, that this organism may have nonspecifically incorporated the soluble M6P on its surface, which led to uptake of L. innocua through the IGFIIR. The M6P binding sites of the IGFIIR have been targeted previously to introduce M6P-coated foreign substances into mammalian cells by use of M6P-coated vesicles (63, 71) or albumin modified with M6P (5, 6). This provides evidence that the IGFIIR can function effectively to transport large particles from the extracellular space into the host cytoplasm.

Interactions of L. monocytogenes with mammalian cells, which involve binding of lectins or lectin-like molecules, including carbohydrate binding components and d-galactose- and glucosamine- or fucosamine-containing proteins, have previously been demonstrated (20-22, 80). Such components have been shown to play an important role in listerial pathogenicity and innate immune responses (32). However, there is as yet no evidence that Listeria spp. contain M6P, as a component of the cell wall, teichoic acids, lipoteichoic acids, or other virulence factors, that is available to interact with IGFIIR during pathogenesis. The carbohydrate binding site of the IGFIIR in domain 3 has been shown to recognize related structures such as phosphodiesters or mannose 6-sulfate (54, 55, 81), and the interaction of Listeria spp. with the IGFIIR may be based on such a related structure that is present on the cell surface of Listeria bacteria.

In conclusion, we have shown that binding and invasion of mammalian cells by L. monocytogenes may involve the IGFIIR and that this may be a novel mechanism of pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by TECRA International, The University of Newcastle, and The Hunter Medical Research Institute.

We thank TECRA International for kindly supplying the strains used in this study. We are most grateful to Keith Ireton (University of Toronto, Canada) for assistance in experimental design and manuscript preparation. We also thank R. MacDonald (Nebraska Medical Centre) for advice on IGFIIR purification techniques and preparation of the manuscript, W. Sly for kind permission to use MS9 and MS9II cell lines, and J. Trapani for the provision of these cell lines.

Editor: J. F. Urban, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abachin, E., C. Poyart, E. Pellegrini, E. Milohanic, F. Fiedler, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Formation of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is required for adhesion and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Dominguez, C., E. Carrasco-Marin, and F. Leyva-Cobian. 1993. Role of complement component C1q in phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine macrophage-like cell lines. Infect. Immun. 61:3664-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 2003. Foodborne disease in Australia: incidence, notifications and outbreaks. Annual report of the OzFoodNet network, 2002. Commun. Dis. Intell. 27:209-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelberg, R., and I. S. Leal. 2000. Mutants of Listeria monocytogenes defective in in vitro invasion and cell-to-cell spreading still invade and proliferate in hepatocytes of neutropenic mice. Infect. Immun. 68:912-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beljaars, L., G. Molema, B. Weert, H. Bonnema, P. Olinga, G. M. Groothuis, D. K. Meijer, and K. Poelstra. 1999. Albumin modified with mannose 6-phosphate: a potential carrier for selective delivery of antifibrotic drugs to rat and human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 29:1486-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beljaars, L., P. Olinga, G. Molema, P. de Bleser, A. Geerts, G. M. Groothuis, D. K. Meijer, and K. Poelstra. 2001. Characteristics of the hepatic stellate cell-selective carrier mannose 6-phosphate modified albumin (M6P(28)-HSA). Liver 21:320-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann, B., D. Raffelsbauer, M. Kuhn, M. Goetz, S. Hom, and W. Goebel. 2002. InlA- but not InlB-mediated internalization of Listeria monocytogenes by non-phagocytic mammalian cells needs the support of other internalins. Mol. Microbiol. 43:557-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bierne, H., S. Dramsi, M. P. Gratacap, C. Randriamampita, G. Carpenter, B. Payrastre, and P. Cossart. 2000. The invasion protein InIB from Listeria monocytogenes activates PLC-gamma1 downstream from PI 3-kinase. Cell Microbiol. 2:465-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bubert, A., M. Kuhn, W. Goebel, and S. Kohler. 1992. Structural and functional properties of the p60 proteins from different Listeria species. J. Bacteriol. 174:8166-8171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrd, J. C., G. R. Devi, A. T. de Souza, R. L. Jirtle, and R. G. MacDonald. 1999. Disruption of ligand binding to the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor by cancer-associated missense mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 274:24408-24416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd, J. C., and R. G. MacDonald. 2000. Mechanisms for high affinity mannose 6-phosphate ligand binding to the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18638-18646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrd, J. C., J. H. Park, B. S. Schaffer, F. Garmroudi, and R. G. MacDonald. 2000. Dimerization of the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18647-18656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49:1129-1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chico-Calero, I., M. Suarez, B. Gonzalez-Zorn, M. Scortti, J. Slaghuis, W. Goebel, and J. A. Vazquez-Boland. 2002. Hpt, a bacterial homolog of the microsomal glucose-6-phosphate translocase, mediates rapid intracellular proliferation in Listeria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:431-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark, E. E., I. Wesley, F. Fiedler, N. Promadej, and S. Kathariou. 2000. Absence of serotype-specific surface antigen and altered teichoic acid glycosylation among epidemic-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3856-3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coley, A. M., N. V. Campanale, J. L. Casey, A. N. Hodder, P. E. Crewther, R. F. Anders, L. M. Tilley, and M. Foley. 2001. Rapid and precise epitope mapping of monoclonal antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum AMA1 by combined phage display of fragments and random peptides. Protein Eng. 14:691-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cossart, P. 2001. Met, the HGF-SF receptor: another receptor for Listeria monocytogenes. Trends Microbiol. 9:105-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cossart, P., and M. Lecuit. 1998. Interactions of Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells during entry and actin-based movement: bacterial factors, cellular ligands and signaling. EMBO J. 17:3797-3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cossart, P., J. Pizarro-Cerda, and M. Lecuit. 2003. Invasion of mammalian cells by Listeria monocytogenes: functional mimicry to subvert cellular functions. Trends Cell Biol. 13:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cottin, J., O. Loiseau, R. Robert, C. Mahaza, B. Carbonnelle, and J. M. Senet. 1990. Surface Listeria monocytogenes carbohydrate-binding components revealed by agglutination with neoglycoproteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 56:301-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cottin, J., R. Robert, P. Leynia de la Jarrige, O. Loiseau, C. Mahaza, B. Carbonnelle, and J. M. Senet. 1991. Specific interaction between Listeria monocytogenes and glycosylated albumins. Res. Microbiol. 142:499-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowart, R. E., J. Lashmet, M. E. McIntosh, and T. J. Adams. 1990. Adherence of a virulent strain of Listeria monocytogenes to the surface of a hepatocarcinoma cell line via lectin-substrate interaction. Arch. Microbiol. 153:282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuzick, J. 1985. A method for analysing case-control studies with ordinal exposure variables. Biometrics 41:609-621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahms, N. M. 1996. Insulin-like growth factor II/cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor and lysosomal enzyme recognition. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 24:136-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahms, N. M., P. A. Rose, J. D. Molkentin, Y. Zhang, and M. A. Brzycki. 1993. The bovine mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. The role of arginine residues in mannose 6-phosphate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 268:5457-5463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devi, G. R., J. C. Byrd, D. H. Slentz, and R. G. MacDonald. 1998. An insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) affinity-enhancing domain localized within extracytoplasmic repeat 13 of the IGF-II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 12:1661-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devi, G. R., A. T. De Souza, J. C. Byrd, R. L. Jirtle, and R. G. MacDonald. 1999. Altered ligand binding by insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptors bearing missense mutations in human cancers. Cancer Res. 59:4314-4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doganay, M. 2003. Listeriosis: clinical presentation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 35:173-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domann, E., S. Zechel, A. Lingnau, T. Hain, A. Darji, T. Nichterlein, J. Wehland, and T. Chakraborty. 1997. Identification and characterization of a novel PrfA-regulated gene in Listeria monocytogenes whose product, IrpA, is highly homologous to internalin proteins, which contain leucine-rich repeats. Infect. Immun. 65:101-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dramsi, S., I. Biswas, E. Maguin, L. Braun, P. Mastroeni, and P. Cossart. 1995. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of inIB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol. Microbiol. 16:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dramsi, S., F. Bourdichon, D. Cabanes, M. Lecuit, H. Fsihi, and P. Cossart. 2004. FbpA, a novel multifunctional Listeria monocytogenes virulence factor. Mol. Microbiol. 53:639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gadjeva, M., S. Thiel, and J. C. Jensenius. 2001. The mannan-binding-lectin pathway of the innate immune response. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13:74-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godar, S., V. Horejsi, U. H. Weidle, B. R. Binder, C. Hansmann, and H. Stockinger. 1999. M6P/IGFII-receptor complexes urokinase receptor and plasminogen for activation of transforming growth factor-beta1. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1004-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg, J. W., W. Fischer, and K. A. Joiner. 1996. Influence of lipoteichoic acid structure on recognition by the macrophage scavenger receptor. Infect. Immun. 64:3318-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greiffenberg, L., Z. Sokolovic, H. J. Schnittler, A. Spory, R. Bockmann, W. Goebel, and M. Kuhn. 1997. Listeria monocytogenes-infected human umbilical vein endothelial cells: internalin-independent invasion, intracellular growth, movement, and host cell responses. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:163-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimme, S., S. Honing, K. von Figura, and B. Schmidt. 2000. Endocytosis of insulin-like growth factor II by a mini-receptor based on repeat 11 of the mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33697-33703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hancock, M. K., D. J. Haskins, G. Sun, and N. M. Dahms. 2002. Identification of residues essential for carbohydrate recognition by the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11255-11264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hancock, M. K., R. D. Yammani, and N. M. Dahms. 2002. Localization of the carbohydrate recognition sites of the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor to domains 3 and 9 of the extracytoplasmic region. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47205-47212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hof, H. 2003. History and epidemiology of listeriosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 35:199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyde-DeRuyscher, R., L. A. Paige, D. J. Christensen, N. Hyde-DeRuyscher, A. Lim, Z. L. Fredericks, J. Kranz, P. Gallant, J. Zhang, S. M. Rocklage, D. M. Fowlkes, P. A. Wendler, and P. T. Hamilton. 2000. Detection of small-molecule enzyme inhibitors with peptides isolated from phage-displayed combinatorial peptide libraries. Chem. Biol. 7:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joh, D., E. R. Wann, B. Kreikemeyer, P. Speziale, and M. Hook. 1999. Role of fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs in bacterial adherence and entry into mammalian cells. Matrix Biol. 18:211-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khuebachova, M., V. Verzillo, R. Skrabana, M. Ovecka, P. Vaccaro, S. Panni, A. Bradbury, and M. Novak. 2002. Mapping the C terminal epitope of the Alzheimer's disease specific antibody MN423. J. Immunol. Methods 262:205-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiess, W., A. Hoeflich, Y. Yang, U. Kessler, A. Flyvbjerg, and B. Barenton. 1993. The insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptor: structure, function and differential expression. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 343:175-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koivunen, E., W. Arap, D. Rajotte, J. Lahdenranta, and R. Pasqualini. 1999. Identification of receptor ligands with phage display peptide libraries. J. Nucl. Med. 40:883-888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kornfeld, S. 1992. Structure and function of the mannose 6-phosphate/insulinlike growth factor II receptors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:307-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kornfeld, S. 1987. Trafficking of lysosomal enzymes. FASEB J. 1:462-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lecuit, M., S. Dramsi, C. Gottardi, M. Fedor-Chaiken, B. Gumbiner, and P. Cossart. 1999. A single amino acid in E-cadherin responsible for host specificity towards the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 18:3956-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li, M., J. J. Distler, and G. W. Jourdian. 1991. Isolation and characterization of mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor from bovine serum. Glycobiology 1:511-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, M. M., J. J. Distler, and G. W. Jourdian. 1989. Phosphomannosyl receptors from bovine testis. Methods Enzymol. 179:304-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu, Q., J. H. Grubb, S. S. Huang, W. S. Sly, and J. S. Huang. 1999. The mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor is a substrate of type V transforming growth factor-beta receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 274:20002-20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowman, H. B. 1997. Bacteriophage display and discovery of peptide leads for drug development. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 26:401-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu, D., J. Shen, M. D. Vil, H. Zhang, X. Jimenez, P. Bohlen, L. Witte, and Z. Zhu. 2003. Tailoring in vitro selection for a picomolar-affinity human antibody directed against VEGF receptor 2 for enhanced neutralizing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 12:12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marron-Terada, P. G., K. E. Bollinger, and N. M. Dahms. 1998. Characterization of truncated and glycosylation-deficient forms of the cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Biochemistry 37:17223-17229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marron-Terada, P. G., M. K. Hancock, D. J. Haskins, and N. M. Dahms. 2000. Recognition of Dictyostelium discoideum lysosomal enzymes is conferred by the amino-terminal carbohydrate binding site of the insulin-like growth factor II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Biochemistry 39:2243-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mengaud, J., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, R. M. Mege, and P. Cossart. 1996. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell 84:923-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mengaud, J., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, R. M. Mege, and P. Cossart. 1997. Grand entry for Listeria. Gastroenterology 112:1045-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milohanic, E., R. Jonquieres, P. Cossart, P. Berche, and J. L. Gaillard. 2001. The autolysin Ami contributes to the adhesion of Listeria monocytogenes to eukaryotic cells via its cell wall anchor. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1212-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morgan, D. O., J. C. Edman, D. N. Standring, V. A. Fried, M. C. Smith, R. A. Roth, and W. J. Rutter. 1987. Insulin-like growth factor II receptor as a multifunctional binding protein. Nature 329:301-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Motyka, B., G. Korbutt, M. J. Pinkoski, J. A. Heibein, A. Caputo, M. Hobman, M. Barry, I. Shostak, T. Sawchuk, C. F. Holmes, J. Gauldie, and R. C. Bleackley. 2000. Mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor is a death receptor for granzyme B during cytotoxic T cell-induced apoptosis. Cell 103:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muhle, C., S. Schulz-Drost, A. V. Khrenov, E. L. Saenko, J. Klinge, and H. Schneider. 2004. Epitope mapping of polyclonal clotting factor VIII-inhibitory antibodies using phage display. Thromb. Haemostasis 91:619-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murayama, Y., T. Okamoto, E. Ogata, T. Asano, T. Iiri, T. Katada, M. Ui, J. H. Grubb, W. S. Sly, and I. Nishimoto. 1990. Distinctive regulation of the functional linkage between the human cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor and GTP-binding proteins by insulin-like growth factor II and mannose 6-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17456-17462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murray, G. J., and D. M. Neville, Jr. 1980. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor-mediated uptake of modified low density lipoprotein results in down regulation of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase in normal and familial hypercholesterolemic fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 255:11942-11948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nolan, C. M., J. W. Kyle, H. Watanabe, and W. S. Sly. 1990. Binding of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) by human cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor/IGF-II receptor expressed in receptor-deficient mouse L cells. Cell Regul. 1:197-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olson, L. J., N. M. Dahms, and J. J. Kim. 2004. The N-terminal carbohydrate recognition site of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279:34000-34009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Polotsky, V. Y., W. Fischer, R. A. Ezekowitz, and K. A. Joiner. 1996. Interactions of human mannose-binding protein with lipoteichoic acids. Infect. Immun. 64:380-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Promadej, N., F. Fiedler, P. Cossart, S. Dramsi, and S. Kathariou. 1999. Cell wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b requires gtcA, a novel, serogroup-specific gene. J. Bacteriol. 181:418-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reddy, S. T., W. Chai, R. A. Childs, J. D. Page, T. Feizi, and N. M. Dahms. 2004. Identification of a low affinity mannose 6-phosphate-binding site in domain 5 of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279:38658-38667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reglier-Poupet, H., E. Pellegrini, A. Charbit, and P. Berche. 2003. Identification of LpeA, a PsaA-like membrane protein that promotes cell entry by Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 71:474-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ripio, M. T., K. Brehm, M. Lara, M. Suarez, and J. A. Vazquez-Boland. 1997. Glucose-1-phosphate utilization by Listeria monocytogenes is PrfA dependent and coordinately expressed with virulence factors. J. Bacteriol. 179:7174-7180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roche, A. C., P. Midoux, V. Pimpaneau, E. Negre, R. Mayer, and M. Monsigny. 1990. Endocytosis mediated by monocyte and macrophage membrane lectins—application to antiviral drug targeting. Res. Virol. 141:243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rowan, N. J., A. A. Candlish, A. Bubert, J. G. Anderson, K. Kramer, and J. McLauchlin. 2000. Virulent rough filaments of Listeria monocytogenes from clinical and food samples secreting wild-type levels of cell-free p60 protein. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2643-2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saraiva, E. M., A. F. Andrade, and W. de Souza. 1987. Involvement of the macrophage mannose-6-phosphate receptor in the recognition of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis. Parasitol. Res. 73:411-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schlech, W. F., III. 1988. Virulence characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes. Food Technol. 42:176-178. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmidt, B., C. Kiecke-Siemsen, A. Waheed, T. Braulke, and K. von Figura. 1995. Localization of the insulin-like growth factor II binding site to amino acids 1508-1566 in repeat 11 of the mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14975-14982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shen, Y., M. Naujokas, M. Park, and K. Ireton. 2000. InIB-dependent internalization of Listeria is mediated by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Cell 103:501-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Slaghuis, J., M. Goetz, F. Engelbrecht, and W. Goebel. 2004. Inefficient replication of Listeria innocua in the cytosol of mammalian cells. J. Infect. Dis. 189:393-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stockwin, L. H., and S. Holmes. 2003. The role of therapeutic antibodies in drug discovery. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:433-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sutherland, P. S., and R. J. Porritt. 1997. L. monocytogenes, p. 333-378. In A. D. Hocking, G. Arnold, I. Jenson, K. Newton, and P. Sutherland (ed.), Foodborne microorganisms of public health significance, 5th ed. AIFST (NSW Branch) Food Microbiology Group, Seaforth, Australia.

- 80.Thuan, B. P., A. M. Calderon de la Barca, G. Buck, S. B. Galsworthy, and R. J. Doyle. 2000. Interactions between listeriae and lectins. Roum. Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 59:55-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tong, P. Y., W. Gregory, and S. Kornfeld. 1989. Ligand interactions of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. The stoichiometry of mannose 6-phosphate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7962-7969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.White, S. J., S. A. Nicklin, T. Sawamura, and A. H. Baker. 2001. Identification of peptides that target the endothelial cell-specific LOX-1 receptor. Hypertension 37:449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wing, E. J., and S. H. Gregory. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes: clinical and experimental update. J. Infect. Dis. 185(Suppl. 1):S18-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yerramalla, U. L., S. K. Nadimpalli, P. Schu, K. von Figura, and A. Hille-Rehfeld. 2000. Conserved cassette structure of vertebrate Mr 300 kDa mannose 6-phosphate receptors: partial cDNA sequence of fish MPR 300. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 127:433-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]