Abstract

Metronidazole (Mz)-resistant Giardia and Trichomonas were inhibited by 1 of 30 new 5-nitroimidazole drugs. Another five drugs were effective against some but not all of the Mz-resistant parasites. This study provides the incentive for the continued design of 5-nitroimidazole drugs to bypass cross-resistance among established 5-nitromidazole antiparasitic drugs.

Metronidazole (Mz) and a related 5-nitroimidazole, tinidazole, are the only drugs recommended for the treatment of trichomoniasis and are the most-prescribed drugs for the treatment of giardiasis. However, clinical resistance to these drugs has been well documented; and in the event of overt clinical resistance to Mz in trichomonads, there is no alternative for treatment, when one keeps in mind the documented cross-resistance between the currently used 5-nitroimidazole drugs and their worldwide availability (7, 8, 18, 23). Some success has been obtained with quinacrine and albendazole in combination with Mz in cases of giardiasis treatment failures (23). On the positive side, a great deal of flexibility is offered by the side chains attached to the imidazole ring structure that bear the all important nitro group (17).

The mechanisms of Mz resistance in Giardia and Trichomonas have been well studied in laboratory-induced resistance (18). It occurs by down-regulation of pathways, especially the enzyme pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) and ferredoxin (Fd) pathway, that activate Mz to its toxic radical state. The PFOR-Fd couple has an electron potential sufficiently low to activate Mz, while no such electron couple is present in the mammalian host (9). In the laboratory we see a threefold down-regulation of PFOR activity in Mz-resistant (Mzr) Giardia duodenalis (14), and in highly Mzr Trichomonas vaginalis the activity of the hydrogenosome organelle is down-regulated such that there is no detectable PFOR or Fd expression (4, 11, 18). Thus, Mz is not activated to its toxic radical state in these cells. On the other hand, it is well documented that clinically Mzr T. vaginalis strains do not have down-regulated hydrogenosomes, and the mechanism of Mz resistance in these cells is not understood (8).

Previously, we showed that some 5-nitroimidazole derivatives were significantly more effective antiprotozoal agents (based on in vitro molar drug concentrations) than Mz against Mz-susceptible (Mzs) parasites but were not as effective against Mzr parasites (17). Given the impetus for the development of 5-nitroimidazole drugs that vary markedly in their efficacies (both positively and negatively), we tested 30 new 5-nitroimidazoles in our anaerobic drug susceptibility screening assay (16) for their efficacies against T. vaginalis and G. duodenalis, with the focus on laboratory-derived Mzr (Mzrl) lines and clinical isolates derived from patients with treatment failures.

Parasites were cultured axenically in anaerobic TYI-S-33 (6), which was modified as described previously (16). Mzs G. duodenalis isolates WB-1B, BRIS/87/HEPU/713 (713), and BRIS/83/HEPU/106 (106) were tested along with their respective Mzrl lines WB-M3, 713-M3, and 106-2ID10 (13, 16). Mzs T. vaginalis isolate BRIS/92/HEPU/F1623 (F1623) and the highly Mzrl line derived from it, F1623-M1 (16), were used throughout. BRIS/92/HEPU/7268 (B7268) (16) and DUR/03/FMUN/36 (DUR36) were the T. vaginalis Mzr clinical (Mzrc) isolates used. Breakpoints for susceptibility versus resistance to Mz were previously described as an MIC of 3.2 μM (with a maximum of 6.3 μM and minimum of 1.6 μM) for Mzs T. vaginalis and 6.3 μM (with a minimum of 3.2 μM and maximum of 12.5 μM in a few cases) for Mzs G. duodenalis (16). The minimum MIC among all assays for Mzr parasites was 25 μM (16). For the purposes of screening new 5-nitroimidazoles, we have directly compared their MICs with those for Mz.

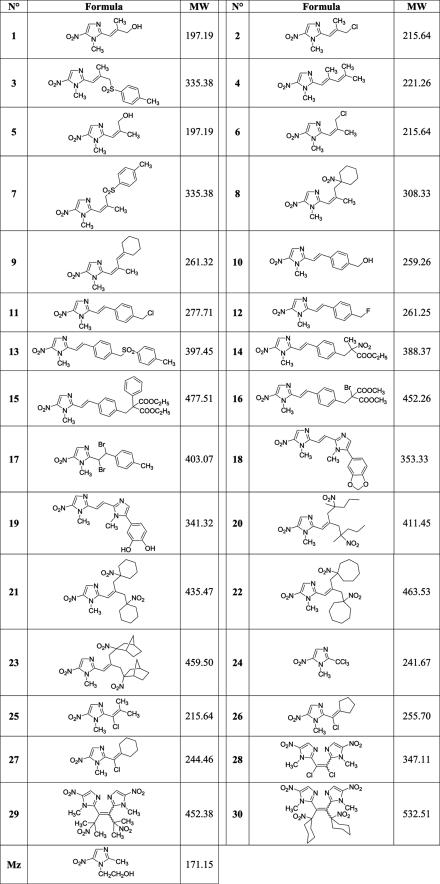

All new 5-nitroimidazole compounds (Fig. 1) were identified by spectral data, purified by chromatography on silica gel columns, and recrystallized from appropriate solvents. Their purities were checked with appropriate controls by thin-layer chromatography and elemental analysis (C, H, N). The purity was always over 99.6%. The synthesis of compounds 1 to 9, 10 to 16, 17 to 19, 20 to 23, and 24 to 28 were as described in references 2, 1, 20, 21, and 22, respectively. The reaction of compound 28 with 2-nitropropane or nitrocyclohexane anion led to the C-alkylation products 29 and 30, respectively, by the SRN1 mechanism.

FIG. 1.

Structures of the 5-nitroimidazole drugs used in this study compared with that of Mz. MW, molecular weight.

Of the 30 compounds tested, compounds 11, 12, 13, 24, 26, and 30 demonstrated MICs against all three Mzs G. duodenalis isolates of ≥100 μM (Mz MIC ≤ 10 μM) (data not shown). Compounds 6, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 28, and 29 had higher MICs than Mz against one or more of the Mzs isolates tested (data not shown). As a result, these drugs were not considered further, except where stated below.

Compounds 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 14, 17, 18, 25, and 27 demonstrated MICs equal to or less than that of Mz (≤10 μM) for all Mzs Giardia and Trichomonas isolates tested and were subsequently assessed against all the Mzrl and Mzrc parasites described above. Of these compounds, compounds 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 25, and 27 were similarly as ineffective as Mz against Mzrl Giardia WB-M3 and 713-M3 (MICs ≥ 50 μM for one or both lines) (data not shown). Compounds 3, 7, 8, 14, 17, and 18 were ≥10-fold more inhibitory than Mz against all Mzrl Giardia (Table 1). In addition, compound 14 had the same MICs of 1 μM (Table 1 and data not shown) against both Mzs and Mzr Giardia parasites. Of these six most effective antigiardial drugs, compound 14 was 16- to 100-fold more inhibitory than Mz against all Mzr parasites (Table 1); compounds 17 and 18 were effective against Mzrc T. vaginalis isolates (fivefold or greater more inhibitory than Mz) but not against Mzrl T. vaginalis (MICs = 50 and 25 μM, respectively) (Table 1); and compounds 3, 7, and 8 were effective only against T. vaginalis Mzrc isolate DUR36 (10- to 16-fold more inhibitory than Mz) (Table 1). The significance of the data presented in Table 1 is the low in vitro MICs for six 5-nitroimidazole compounds against some or all of the Mzr parasites tested. No other 5-nitroimidazole compounds tested so far were inhibitory to the Mzr parasites used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of MICs of the six most effective new 5-nitroimidazole drugs against Mzr G. duodenalis and T. vaginalis lines and isolates

| Druga | MIC (μM)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MzrlGiardia

|

Trichomonas

|

|||||

| WB-M3 | 713-M3 | 106-2ID10 | Mzrl F1623-M1 | Mzrc

|

||

| B7268 | DUR36c | |||||

| Mz | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.1 | 1.6 |

| 18 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 25 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| 17 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 50 | 10 | 6.3 |

| 8 | 3.1 | 5 | NDb | 50 | 50 | 6.3 |

| 7 | 3.1 | 5 | ND | 50 | 50 | 6.3 |

| 3 | 3.1 | 1 | ND | 50 | 50 | 10 |

drugs are listed in the order of their efficacies.

ND, not done.

Isolate collected in Durban, South Africa and established in culture at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Natal.

The most effective drug overall, compound 14, differs in structure from compound 16 (Fig. 1) by the remote substituents of the side chain attached at the 2 position on the nitroimidazole ring, notably, a nitro group in compound 14 but not in compound 16, which showed no inhibition of two Mzs G. duodenalis isolates (MICs = 100 μM). Other compounds with remote nitro groups (compounds 20, 21, 22, 23, 29, and 30; Fig. 1) did not inhibit Mzr parasites (MICs ≥ 100 μM). We also tested a number of quinoxaline and 3,4-diphenylfuran derivatives with and without nitro groups (unpublished synthesis data) and p-nitrobenzyl derivatives (3), none of which were effective antiprotozoal agents (data not shown).

Of the highly effective antitrichomonal 5-nitroimidazoles, compound 17 was selected for extended studies, due to its inhibition of Mzrc T. vaginalis (Table 1) and its ease of preparation. We measured the anaerobic MICs (16) of compound 17 and Mz against 31 T. vaginalis clinical isolates collected in South Africa. All Mzs isolates were susceptible to compound 17, with at least fourfold lower MICs than that of Mz (data not shown). Four isolates demonstrated some level of Mz resistance (MICs for Mz of 12.5, 12.5, 50, and 100 μM, respectively) but had MICs with compound 17 of 1.6, 3.1, 6.3, and 6.3 μM, respectively. The most highly Mzr isolate was DUR36 (Table 1). Compounds 14, 17, and 18 therefore provide precedence for the design of new 5-nitroimidazole antitrichomonal drugs. It has been claimed that the eradication of trichomoniasis may well be the single most cost-effective step in human immunodeficiency virus infection incidence reduction (5, 10, 12), and for this reason the development of drugs for the treatment of cases of Mzrc T. vaginalis has been a focus of our work (8, 16).

Previously, we reported that among a 5-nitroimidazole series of compounds, the most antimicrobial and antiparasitic compounds showed a greater resonance conjugation in the molecular structure (17, 19). For this study, we have synthesized under mild conditions and in good yields highly conjugated 5-nitroimidazole derivatives using electron transfer reactions (SRN1, LD-SRN1, bis-SRN1, and ERC1 [1, 2, 20, 21, 22]). By increasing the conjugated system, we have developed some highly active compounds, especially the C-alkylation products obtained by LD-SRN1, compounds 8 and 14. The present study again demonstrates the importance of the 5-nitroimidazole side chain in antiparasitic activity (e.g., compounds 3 and 7 are E and Z isomers, and the differences between the antiprotozoal activities of compounds 14 and 16 and between compounds 18 and 19). These dramatic differences may relate to solubility and membrane permeability. The positive influence of bromine (compound 17), a sulfonyl group (compounds 3 and 7), or a dioxole nucleus (compound 18) were noted, but deprotection of the remote dioxole ring in compound 18 resulted in the formation of the diphenol compound 19, which was detrimental to protozoocidal activity.

These data suggest that the 5-nitro group is highly active in compound 14, but it does not explain why this drug is so active against Mzrl T. vaginalis, which supposedly does not have the ability to reduce Mz (4). We have previously identified alternative 2 oxoacid oxidoreductase (OR) activity in Mzrl T. vaginalis (4), and it is possible that these alternative ORs are responsible for the activation of compound 14 to its toxic radical state.

There are examples in the literature of patients who have failed to respond to all antigiardial or antitrichomonal treatments (7, 23). Here we have shown that at least three different 5-nitroimidazole compounds, including one that is readily synthesized, inhibited highly Mzrl G. duodenalis and Mzrc T. vaginalis isolates. The clinical application of such drugs may well overcome the documented cross-resistance among the 5-nitroimidazole drugs, and the lead compounds described here provide the basis from which new 5-nitroimidazole drugs clinically active against Mzr Trichomonas and Giardia can be derived.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Wim Sturm, Sarita Naidoo, and staff at the Medical Faculty, University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa.

This work was supported by ACITHN: a grant to support a field visit to Durban in 1999 and continued support of Jacqueline Upcroft. We gratefully acknowledge the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust for a fellowship to Jacqueline Upcroft in 2003 for work carried out in South Africa and the NHMRC, which has supported some of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benakli, K., M. Kaafarani, M. P. Crozet, and P. Vanelle. 1999. Competition between C- and O-alkylation reactions in 5-nitroimidazole series: influence of nucleophile. Heterocycles 51:557-565. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benakli, K., T. Terme, J. Maldonado, and P. Vanelle. 2002. A convenient synthesis of highly conjugated 5-nitroimidazoles. Heterocycles 57:1689-1695. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benakli, K., T. Terme, and P. Vanelle. 2002. Preparation of new chlorambucil analogs by bis-SRN1 methodology. Synthetic Commun. 32:1859-1865. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, D. M., J. A. Upcroft, H. N. Dodd, N. Chen, and P. Upcroft. 1999. Alternative 2-keto acid oxidoreductase activities in Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 98:203-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowden, F. J., and G. P. Garnett. 1999. Why is Trichomonas vaginalis ignored? Sex. Transm. Infect. 75:372-374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, C. G., and L. S. Diamond. 2002. Methods for cultivation of luminal parasitic protists of clinical importance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:329-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowell, A. L., K. A. Sanders-Lewis, and W. E. Secor. 2003. In vitro metronidazole and tinidazole activities against metronidazole-resistant strains of Trichomonas vaginalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1407-1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunne, R. L., L. A. Dunn, P. Upcroft, P. J. O'Donoghue, and J. A. Upcroft. 2003. Drug resistance in the sexually transmitted protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. Cell Res. 13:239-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards, D. I. 1993. Nitroimidazole drugs—action and resistance mechanisms. I. Mechanisms of action. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guenthner, P. C., W. E. Secor, and C. S. Dezzutti. 2005. Trichomonas vaginalis-induced epithelial monolayer disruption and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication: implications for the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Infect. Immun. 73:4155-4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulda, J. 1999. Trichomonads, hydrogenosomes and drug resistance. Int. J. Parasitol. 29:199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorvillo, F., L. Smith, P. Kerndt, and L. Ash. 2001. Trichomonas vaginalis, HIV, and African-Americans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:927-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Townson, S. M., H. Laqua, P. Upcroft, P. F. L. Boreham, and J. A. Upcroft. 1992. Induction of metronidazole and furazolidone resistance in Giardia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86:521-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townson, S. M., J. A. Upcroft, and P. Upcroft. 1996. Characterisation and purification of pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase from Giardia duodenalis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 97:183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reference deleted.

- 16.Upcroft, J. A., and P. Upcroft. 2001. Drug susceptibility testing of anaerobic protozoa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1810-1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upcroft, J. A., R. W. Campbell, K. Benakli, P. Upcroft, and P. Vanelle. 1999. Efficacy of new 5-nitroimidazoles against metronidazole-susceptible and -resistant Giardia, Trichomonas, and Entamoeba spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:73-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upcroft, P., and J. A. Upcroft. 2001. Drug targets and mechanisms of resistance in the anaerobic protozoa. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:150-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanelle, P., and M. P. Crozet. 1998. Recent advances in the chemical synthesis of novel nitroimidazoles via electron transfer reactions. Recent Res. Dev. Organic Chem. 2:547-566. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanelle, P., J. Meuche, J. Maldonado, M. P. Crozet, F. Delmas, and P. Timon-David. 2000. Functional derivatives of 5-benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-1-methyl-1H-imidazole-2-carbaldehyde and evaluation of leishmanicidal activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 35:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanelle, P., K. Benakli, J. Maldonado, and M. P. Crozet. 1998. Synthesis of new 2-highly branched 5-nitroimidazoles by bis-SRN1 methodology. Heterocycles 48:181-185. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanelle, P., K. Benakli, L. Giraud, and M. P. Crozet. 1999. Synthesis of tetrasubstituted ethylenic compounds from a gem-trichloroimidazole derivative by electron transfer reactions. Synlett. 6:801-803. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright, J. M., L. A. Dunn, P. Upcroft, and J. A. Upcroft. 2003. Efficacy of antigiardial drugs. Exp. Opin. Drug Safety 2:529-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]