Abstract

The pseudorabies virus (PRV) UL54 homologs are important multifunctional proteins with roles in shutoff of host protein synthesis, transactivation of virus and cellular genes, and regulation of splicing and translation. Here we describe the first genetic characterization of UL54. We constructed UL54 null mutations in a PRV bacterial artificial chromosome using sugar suicide and λRed allele exchange systems. Surprisingly, UL54 is dispensable for growth in tissue culture but exhibits a small-plaque phenotype that can be complemented in trans by both the herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP27 and varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 4 proteins. Deletion of UL54 in the virus vJSΔ54 had no effect on the ability of the virus to shut off host cell protein synthesis but did affect virus gene expression. The glycoprotein gC accumulated to lower levels in cells infected with vJSΔ54 compared to those infected with wild-type virus, while gK levels were undetectable. Other late gene products, gB, gE, and Us9, accumulated to higher levels than those seen in cells infected with wild-type virus in a multiplicity-dependent manner. DNA replication is also reduced in cells infected with vJSΔ54. UL54 appears to regulate UL53 and UL52 at the transcriptional level as their respective RNAs are decreased in cells infected with vJSΔ54. Interestingly, vJSΔ54 is highly attenuated in a mouse model of PRV infection. Animals infected with vJSΔ54 survive twice as long as animals infected with wild-type virus, and this results in delayed accumulation of virus-specific antigens in skin, dorsal root ganglia, and spinal cord tissues.

Pseudorabies virus (PRV) is a porcine alphaherpesvirus that can infect most mammals except for higher-order primates, such as humans. Infection in all hosts, except for its natural reservoir, the pig, is lethal. However, only adult pigs are capable of recovering from infection as mortality decreases with increasing age (54, 96). Because of the neurotropic nature of PRV, several experimental models have been developed that utilize PRV as a tool to trace circuits in the mammalian nervous system (8, 21). Yet it has become apparent that these viruses are also useful tools in the study of herpesvirus pathogenesis (11, 21).

Characteristic of the alphaherpesviruses, PRV infection is initiated by multistep attachment of virus glycoproteins to cell surface receptors, resulting in fusion of the virus envelope to the plasma membrane (28, 54, 58, 87, 88). Virus gene expression is temporally regulated in a cascade. Genes are grouped into three kinetic classes: immediate-early (IE), early (E), and late (L). The prototypic alphaherpesvirus, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), possesses several IE gene products that are involved in the regulation of gene expression; however, only the ICP4 PRV homolog, IE180, is expressed with IE kinetics (38). The homologs of the HSV-1 IE regulatory proteins ICP0 and ICP27 are expressed with E kinetics in PRV. One of these proteins, although not well studied in PRV, is the HSV-1 ICP27 homolog, UL54 (5, 36, 37).

ICP27 is the only protein known to have homologs in all human herpesviruses and across all three (α, β, and γ) herpesvirus subfamilies (6, 13, 14, 17, 29, 39, 53, 59, 71, 91, 98). In most cases, the ICP27 homologs are essential for growth in tissue culture (30, 72, 78). If not essential, as is the case for the human cytomegalovirus homolog, UL69, deletion results in severe growth defects (19, 35, 97). The ICP27 homologs are important multifunctional proteins that play roles at both the transcriptional (40, 89) and posttranscriptional levels. HSV ICP27 is perhaps the most extensively characterized of all the homologs. It can act as both a transactivator and a transrepressor (33, 40, 48, 51, 89, 93). It aids in the shutoff of host protein synthesis (32, 34), most probably through its ability to inhibit host splicing (74). ICP27 stabilizes the 3′ end of labile transcripts (12, 57), affects polyadenylation site usage (48-50), redistributes splicing components (65, 75), and binds to and shuttles intronless transcripts (52, 74, 86). Additionally, ICP27 may also regulate the translation of virus and/or host transcripts (20, 25) and the inhibition of HSV-1-dependent apoptosis (2, 3).

Like many herpesviruses (reviewed in reference 1), the PRV genome has been cloned into a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) (83), permitting mutagenesis through the use of allele exchange systems in Escherichia coli. Recombination systems in E. coli are a vast improvement, in speed and efficiency, over the traditional methods of mutagenesis through homologous recombination in mammalian tissue culture systems. Using a sugar suicide system for allele exchange (83) and a λRed recombineering protocol (15, 16, 90), we created two UL54-null deletion mutants (vJSΔ54 and vJSΔ54N) in the PRV BAC, pBecker3 (83). While viruses with a deletion of UL54 are viable, they exhibit slow-growth phenotypes with cell type-specific degrees of severity in growth. We also show that the decreased plaquing efficiency of vJSΔ54 is abrogated by expression of either the HSV ICP27 or varicella-zoster virus (VZV) open reading frame 4 (ORF4) proteins. The deletion mutant, vJSΔ54, is able to shut off host cell protein synthesis in a manner similar to wild-type (WT) virus. However, compared to WT, the mutant exhibits aberrant expression of several E and L genes and is highly attenuated in a mouse model of PRV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Vero (green monkey kidney) and 2-2 (Vero cells with the HSV-1 ICP27 gene under the control of the ICP27 promoter [84]) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum (HyClone Laboratories Inc., Logan, UT). The 2-2 cell medium was supplemented with 500 μg/ml of G418 (Gibco BRL). PK(15) (porcine kidney) and RK13 (rabbit kidney) cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Laboratories Inc.). V4R-13 cells (a Vero-based cell line stably transfected with the VZV homolog ORF4 under the control of a cadmium-inducible promoter; provided by J. Cohen) (56) were maintained in DMEM containing 10% dialyzed FBS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 500 μg/ml of G418 and induced as described previously (56). Unless otherwise indicated, all media used, including overlay media, contained 100 U of penicillin per ml and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (Pen-Strept; Gibco BRL).

Viruses.

The wild-type PRV used was vBecker3, generated after transfection of Vero cells with pBecker3 (83). Mutant PRVs (vJSΔ54, vJSΔ54R, and vJSΔ54N) were made by manipulating pBecker3 and transfecting mammalian cells (see below).

Plasmids.

Unless otherwise noted, all PCRs were performed with PfuTurbo polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) supplemented with 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide. pJSPrB5′ was generated by cloning the 5′ BamHI fragment (5) from nucleocapsid DNA from vBecker3 into the BamHI site of pZErO2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). pJAS40 was created by ligating the 7.4-kb 5′ BamHI fragment from pJSPrB5′ to pGS284 digested with BglII. The N-terminal UL54-Flag fusion plasmid, pJSPr54Nf, was constructed by cloning the BamHI-EcoRI-digested PCR product amplified from pJSPrB5′ with the primers Bam5′PrUL54Up (5′-ACCGGATCCATGGAGGACAGCGGCAAC-3′) and Eco3′PrUL54stopLo(5′-ACCGAATTCTCAAAACAGGTGGTTGCA-3′) into the BamHI-EcoRI-digested pCMV-Tag2B (Stratagene) vector. The UL54 deletion BAC, pJSΔ54, was created by first amplifying the 300-bp homology region immediately upstream of the UL54 start site and the last 252 bp of the UL54 ORF plus 48 bp of sequence downstream of the UL54 stop site by PCR (Fig. 1C). The 300 bp of the upstream UL54 homology region (Fig. 1C) for allele exchange in E. coli was amplified by PCR from pJSPr-B5′ with the primers Bgl2-5′UL54UP (5′-CCAGATCTCTGGAGCTCCTGGCGGCG-3′) and EcoRI-5′UL54LO (5′-CCGAATTCTCAGACCGTGGTGCGAGCGG-3′). The 300 bp of the downstream UL54 homology region (Fig. 1C) for allele exchange in E. coli was amplified by PCR from pJSPr-B5′ with the primers EcoRI-3′UL54UP (5′-TGAGAATTCGGCACACTGGTGATGCTGGC-3′) and Bgl2-3′UL54LO (5′-CCAGATCTAGGGGAGGACGACAGACTC-3′). The two PCR products were joined after a PCR that used their products as templates and Bgl2-5′UL54UP and Bgl2-3′UL54LO as primers. The resulting product was cloned into the EcoRV site of pGEM-5zf(+) (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) to generate pJSPrΔ54H. The kanamycin (KAN) resistance determinant (Kanr cassette) from pUC4K (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) was released by EcoRI digestion and cloned into the EcoRI site of pJSPrΔ54H to yield pJSPrΔ54HK. The homology regions and the Kanr cassette (Fig. 1C, H1) were released from pJSPrΔ54HK with BglII and ligated to the allele exchange vector, pGS284 (83), digested with BglII to generate pJSPrΔ54AE. The BACs pJSΔ54 and pJSΔ54R were created by allele exchange in E. coli using the vectors, pJSPrΔ54AE or pJAS40, respectively (seebelow).

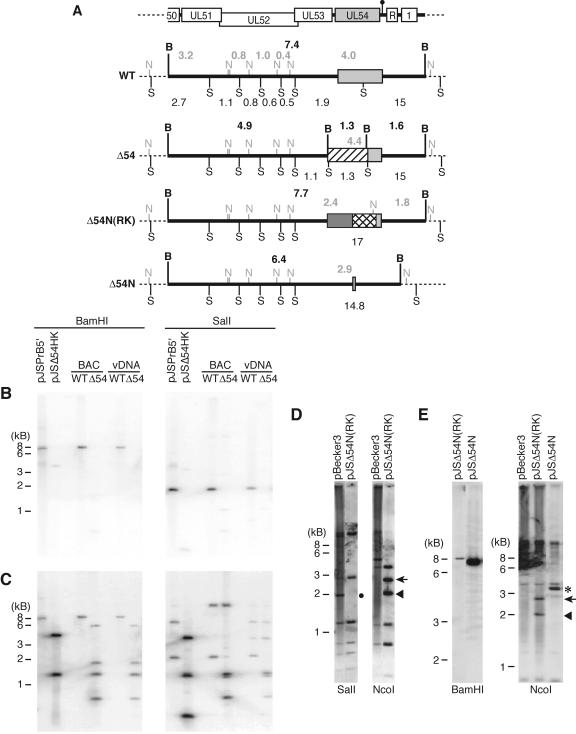

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the UL54 loci in BAC and virus DNAs. (A) Schematic diagram of the PRV genome depicting the unique long (UL), unique short (US), internal repeat (IR), and terminal repeat (TR) regions (black boxes). (B) Schematic diagram of the 7.4-kb 5′ BamHI fragment containing the UL54 locus (light gray box). The UL54 poly(A) site is identified by the black circle, while the arrows denote the UL52, UL53, and UL54 3′ coterminal transcripts that utilize the UL54 poly(A) site. The ∼500-bp repeat region (R) and the ORF1 (1) gene downstream of UL54 are shown. The light gray lines (P1 to P5) depict regions of the 5′ BamHI fragment used as probes for Northern and Southern analyses (see Materials and Methods). (C) Schematic diagram of the UL54 locus in the Δ54 BAC and virus DNAs. The light gray boxes represent UL54 sequence, while the hatched boxes represent the kanamycin resistance determinant (Kanr). The dotted vertical lines delineate the 300-bp homology regions used for allele exchange. Depicted beneath the WT UL54 locus is the targeted locus used as a probe (P6) that was also cloned (H1) into a sugar suicide vector for homologous recombination in E. coli. (D) Schematic diagram of the UL54 locus in the Δ54N(RK) BAC and of the Δ54N BAC and virus DNAs. The crosshatched and dark gray boxes represent the selectable (Neo) and counterselectable (RpsL) markers, respectively. The dotted vertical lines define the homology regions used for allele exchange [64 and 70 bp for Δ54N(RK) and Δ54N, respectively]. Depicted beneath the WT UL54 locus is the targeted locus (H2), which contains only 21 bp of 3′ UL54 sequence. H2 was used as a PCR product in a λRed system for homologous recombination in E. coli to generate the Δ54N(RK) BAC. Illustrated beneath the Δ54N(RK) UL54 locus is the UL54-null locus (H3) containing only 11 bp of 3′ UL54 sequence, which was used as a PCR product in a λRed system for homologous recombination in E. coli to generate the Δ54N BAC.

The BACs pJSΔ54N(RK) and pJSΔ54N were generated by allele exchange in E. coli utilizing the λRed system for homologous recombination (see below). To create pJSΔ54N(RK), a targeting cassette was generated using PCR (Fig. 1D, H2). The selection-counterselection cassette of RpsL-Neo from the pRpsL-Neo plasmid (GeneBridges, Dresden, Germany) was flanked by 64 bp of UL54 homology using oligonucleotides containing the regions of homology and sequence complementary to the ends of the RpsL-Neo cassette (Fig. 1D). The 64 bp that compose the 5′ end of the targeting vector terminate at the −1 position relative to the UL54 start codon. The 64 bp downstream of the UL54 homology overlap with the last 21 bp of the UL54 ORF (Fig. 1D).

The PCR product was generated as follows: the RpsL-neo-UL54 homology cassette (Fig. 1D, H2) was amplified from pRpsL-neo using the ET-UL54up (5′-GGGTTAAAGGCGCCCCGCCGCCCGCCACCTGCACACCGCGGCCCC GCTCGCACCACGGTCGGCCTGGTGATGATGGCGGGATC-3′) and the ET-UL54lo (5′-ACCAGAGAGGTACGGTTCAACAGTTTTATTCAAAACAGGTGGTTGCAGTAAAAGTACTTCTCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAGAAGG-3′) primers to generate pJSΔ54N(RK) from pBecker3. Using the double-stranded targeting cassette PCR product (Fig. 1D, H2) and the mini-λ, the RpsL and Neo genes were targeted to the UL54 ORF to create the pJSΔ54N(RK) BACmid (see below).

The pJSΔ54N BAC was created using a 140-bp PCR product generated from two 40-mers and a 100-mer template. This 140-mer contains 70 bp of upstream UL54 homology and 70 bp of downstream homology (Fig. 1D, H3). The 40-bp primers, UL54-loopout1 (5′-CGGGGACGACGGGTTAAAGGCGCCCCGCCGCCCGCCACCT-3′) and UL54-loopout3 (5′-GGAGATGGGGAGGACGACAGACTCGTGCACACCAGAGAGG-3′), were used to create a 140-bp product using the 100-bp oligonucleotide UL54-loopout2 (5′-CGCCCCGCCGCCCGCCACCTGCACACCGCGGCCCCGCTCGCACCACGGTCACCTGTTTTGAATAAAACTGTTGAACCGTACCTCTCTGGTGTGCACGAGT-3′) as a template (Fig. 1D, H3) to generate pJSΔ54N from pJSΔ54N(RK) with the λRed allele exchange system (see below).

BACs. (i) Allele exchange in E. coli.

Allele exchange was performed as described previously (83). Conjugal transfer of the allele exchange vectors occurred following cross-streaking of GS500 (82) containing pBecker3 or pJSΔ54 with the bacteria strain S17λpir containing pJSPrΔ54AE or pJAS40, respectively, on Luria broth (LB) plates without antibiotics and incubation overnight at 37°C. Each intersection from the crossed streaks was inoculated into 10 ml of LB plus 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol (LB-Cm) and 25 μg/ml ampicillin (AMP) and incubated overnight, rotating, at 37°C to select for recombinants. To select for deletion of the allele exchange vector from pBecker3 or pJSΔ54, 5 μl of each overnight culture was inoculated into 10 ml of LB-CHL and incubated overnight at 37°C. The cultures were serially diluted (10−3, 10−4, and 10−5), and 50 μl of each dilution was plated onto LB-CHL containing 5% sucrose or LB-CHL and incubated at 30°C overnight. Colonies from the LB-CHL-sucrose plates were replica streaked onto LB-CHL and LB-AMP plates. Patches that grew on LB-CHL but not LB-AMP were grown in LB-Cm and further screened for Kanr and then by PCR, dot blot, and/or Southern blot analysis (see below).

(ii) λRed-mediated allele exchange in E. coli. (a) Introduction of the mini-λ into E. coli.

The GS500 strain containing the pBecker3 BAC (82) was grown and made competent, as previously described (16, 90). The competent cells were electroporated using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at 25 μF and 200 Ω with 25 ng of mini-λ (16), which had been prepared from W3110 cells after a 15-min induction at 42°C (16) (provided by D. Court, National Institutes of Health). The transformants were allowed to recover by shaking at 30°C for 2 h, plated onto LB-CHL plates containing 15 μg/ml tetracycline, and then incubated at 30°C overnight.

(b) Induction of the λRed system.

GS500 bacteria (82) containing the BAC of interest and the mini-λ were grown and made competent as above. The λRed genes were induced prior to making the cells competent by incubating the cultures in a 42°C shaking H2O bath for 15 min. The uninduced control cultures were kept on ice during the induction. The competent cells were then transformed by electroporation (see above) with the PCR product (Fig. 1D, H2 or H3). After transformation, the cells were allowed to recover for 2 to 3 h by incubation at 30°C with shaking, and then they were plated onto selection media and incubated overnight at 30°C. Colonies were replica patched onto LB-Cm, LB-KAN, and LB plus 15 μg/ml streptomycin plates to determine whether allele exchange had occurred.

(iii) BAC DNA preparation.

BAC DNA was prepared using a Montage-96 miniprep kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The QIAGEN tip-20 kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) was used with 20 ml of culture and the QIAGEN tip-500 kit was used with 500 ml of culture. All BAC DNAs were stored at 4°C.

Construction of recombinant viruses.

Recombinant PRVs were generated by transfecting 1 × 106 Vero cells with 3 μg of BAC DNA using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). At 3 to 5 days after transfection, and once significant cytopathic effect was observed, the cells were collected and freeze-thawed three times. These lysates were then used to infect larger flasks or plates of cells to generate virus stocks.

Virus preparation.

Vero cell monolayers were infected at low multiplicities of infection (MOIs) and incubated at 37°C for 2 to 3 days. Infected cells were scraped into the medium and pelleted by low-speed centrifugation. The infected cell pellet was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 2.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 138 mM NaCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O), resuspended in DMEM containing 1% bovine calf serum, and subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles. The virus was then titrated on Vero cells.

Plaque assays.

Plaque assays were performed on PK(15), Vero, 2-2 (81), and V4R-13 (56) cells. For induction of ORF4 expression in V4R-13 cells, 10 μM CdCl2 was added to the medium at the indicated times. After 1 h of adsorption at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 1 to 2% FBS, methylcellulose overlay medium (DMEM containing 1.5% methylcellulose and 1% FBS) was added to the infected cell monolayers. Plates were incubated at 37°C for several days, and the cells were fixed with methanol. The cell monolayers were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and plaques were counted.

Quantification of plaque sizes.

After plaques were stained with crystal violet, they were photographed with a Nikon digital camera and analyzed using the Canvas version 8.0.5 software package (Deneba Systems, Inc., Saanichton, British Columbia, Canada). Fifty to sixty plaques were measured per infection except for PK(15) cells infected with vJSΔ54, where only 39 plaques were measured. The plaque diameters were measured in inches and averaged, and the standard deviations were calculated.

Virus growth assays.

Growth assays were performed as previously described (45). Growth curves represent the average of three independent infections. Each was titrated in duplicate.

Preparation and analysis of DNA. (i) Virus DNA preparation.

DNA was prepared from infected Vero or PK(15) cells as described previously (45).

(ii) BAC and PRV Southern blot analysis.

DNA samples (100 to 500 ng) were digested with the indicated restriction enzymes and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization following depurination and alkaline transfer of the DNA to Nytran membranes (Schleicher and Schuell Bioscience, Keene, NH).

The membranes were hybridized with biotinylated probes made using the NEB Phototope-Star Detection kit (Beverly, MA) with the indicated template DNAs, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The hybridized probes were detected by chemiluminescence using an NEB Phototope-Star Detection kit after the blots were exposed to X-ray film.

(iii) Dot blot analysis.

BAC DNAs were loaded onto a SS-Nytran membrane (Schleicher and Schuell) using the Bio-Dot apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The DNA samples were denatured as described below for PRV slot blots, loaded into the wells, and allowed to sit at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. A vacuum was applied, and the wells were washed with 100 μl of 0.4 N NaOH. The membranes were briefly washed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and UV cross-linked as described above. The membranes were then prehybridized, hybridized with biotinylated probes, and detected as described above. The probes used were the BamHI-PstI fragment from pJSPr54Nf containing UL54 nucleotides (nt) 1 to 718 (Fig. 1B, P5) and the 4.9- kb BamHI-MseI fragment from pJSPr-B5′ (Fig. 1B, P2).

PCR analysis of recombinant virus DNA.

Reactions were set up containing 1 mM spermidine, 1× cloned Pfu buffer (Stratagene), 250 μM dATP, 250 μM dCTP, 250 μM dGTP, 250 μM dTTP, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 250 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 μM concentration of primer PrUL54startUP (5′-ATGGAGGACAGCGGCAACAG-3′), 0.5 μM concentration of primer PrUL54-624LO (5′-CGAGGCGAGGGACTCCGTC-3′), 1 μl of Perfect Match solution (Stratagene), and 2.5 U of PfuTurbo polymerase. The cycling parameters were as follows: 98°C for 5 min to denature, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, with a final 7-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were detected by ethidium bromide staining after separation on a 0.8 to 1% agarose gel.

DNA replication. (i) DNA preparation.

PK(15) cells were seeded onto six-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/well and infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of either 10 or 0.01. At 1 h postinfection (hpi), the 1-h time point was placed at −80°C, while 1 ml of DMEM with 1% FBS was added to the remaining samples, and they were incubated at 37°C for 16.5 h. At the indicated times, cells were harvested and resuspended in 475 μl of DNA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 200 μg/ml proteinase K, and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). The samples were incubated at 50°C overnight, and 170 μl of saturated NaCl was added. After being subjected to shaking for 10 min at RT, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge for 10 min; subsequently, 469 μl of isopropanol was added to the supernatant, and the sample was incubated at RT for 1 h. The DNA was pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in 333 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (∼3 × 105 cell equivalents per 100 μl). Each DNA sample was denatured by adding an equal volume of denaturation solution (0.5 M NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl) and incubated at RT for 15 min.

(ii) PRV slot blot analysis.

One hundred microliters of serially diluted denatured DNA was analyzed by slot blot onto SS-Nytran membranes (Schleicher and Schuell). The biotinylated DNA probe for detection of PRV DNAs was the 7.5-kb 5′ BamHI fragment from pJSPr-B5′ (Fig. 1B, P1) labeled with biotin as described for Southern blot analysis.

Analysis of virus RNAs. (i) Total RNA preparation.

PK(15) cells were infected at an MOI of 10. At 4, 8, or 12 hpi, infected cells were scraped, pelleted, and frozen at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated from the cell pellets using the High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations were determined by measuring absorption at A260.

(ii) Northern blot analysis.

RNA samples were denatured by incubating at 55°C for 15 min in 1× MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer (20 mM MOPS, pH 7, 5 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA), 6% formaldehyde, and 50% formamide. Five micrograms of denatured RNA in RNA loading buffer (1 mM EDTA, pH 8, 50% glycerol, 0.25% bromophenol blue, 0.3% ethidium bromide) was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel containing 1.1% formaldehyde and 1× MOPS and electophoresed at 25 V overnight in 1× MOPS. The RNAs were partially hydrolyzed by incubating the gels in 0.01 N NaOH for 20 min, equilibrated in 10× SSC for 5 min, and transferred onto SS-Nytran nylon membranes by upward capillary action in 10× SSC overnight. The membranes were washed in 5× SSC; UV cross-linked; prehybridized in 50% formamide, 5× Denhardt's reagent, 0.5% SDS, and 100 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA; and hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA probes at 42°C overnight. Radioactive DNA probes were generated using a High Prime DNA labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics). The Northern blot DNA probes and templates used to generate the probes were as follows: for the UL52 probe (nt 1065 to 2328), a PCR product amplified from pJSPrB5′ with the UL52PR2 (5′-CAACATCCGCGACTACGTC-3′) and UL52PR5 (5′-GGTCGTCGAAGCCCGGGG-3′) primers (Fig. 1B, P3); for the UL53 probe (nt 382 to 1000), a PCR product amplified from pJSPrB5′ with the UL53PR2 (5′-GCCGAGTTCCTGACCCCG-3′) and UL53PR3 (5′-GCGGTGTGCAGGTGGCGG-3′) primers (Fig. 1B, P4); and for the porcine glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe, a reverse transcription-PCR product amplified with the C. therm One-Step RT-PCR system (Roche Diagnostics) from PK(15) total RNA with the 5′-AGCTGAACGGGAAGCTCACTG-3′ and 5′-CCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCG-3′ primers to human GAPDH (NM_002046).

Protein synthesis assay.

RK13 cells seeded at 3 × 106 cells/plate (60-mm2 plate) in 1% FBS and DMEM were infected at an MOI of 10 for 1 h at 37°C with rocking every 15 min and then overlaid with fresh medium. At the indicated times, the cells were washed three times with Met−/Cys− DMEM (DMEM lacking methionine and cysteine [Specialty Media, Inc., Lavallette, NJ] containing 1% dialyzed FBS [Sigma]); 2 ml of medium was added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. After the medium was removed, 500 μl of Met−/Cys− DMEM containing 100 μCi of Trans-35S label (1,175 Ci/mmol; ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA) was added, and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The plates were placed on ice, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped into 1 ml of ice-cold PBS, and pelleted at 4°C in a microcentrifuge at 2,500 rpm. The pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of 1.5× SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 0.001% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol), boiled for 10 min, and eletrophoresed through a 4% stacking-10% separating SDS polyacrylamide gel at 80 V overnight in 1× SDS running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS). The gels were dried at 80°C for 2 h and exposed to film.

Western blot analysis.

PK(15) cells were infected at either high (MOI of 10) or low (MOI of 0.5) MOIs. At various times postinfection, whole-cell extracts were generated. The cells were collected and resuspended in NET-2 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% NP-40) plus 1× Complete protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) and sonicated twice for 30 s on ice. An equal volume of 2.5× SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added. The lysates were then either boiled for 10 min or incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Equal amounts of protein from each extract were electrophoresed through 4% stacking-7.5% separating SDS polyacrylamide gels or a precast 12% or 4 to 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). The polyacrylamide gel was electrophoresed in 1× SDS running buffer, while the precast gels were electrophoresed in 1× MOPS buffer (Invitrogen). The gels were soaked in 1× transfer buffer (47.5 mM Tris, 38.3 mM glycine, 0.037% SDS, 20% methanol) for 15 min and then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes overnight at 20 V. The membranes were blocked for 2 h in 4% nonfat milk in PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) and then incubated for 1 h in a 1:1,000 primary antibody solution in 4% nonfat milk in PBST. The membranes were washed three times for 5 min each in PBST and then incubated for 1 h in secondary antibody solution (1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-mouse, or rabbit anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies) (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Inc. [KPL], Gaithersburg, MD). The membranes were then washed three times with PBST and once with PBS, developed using a 1:1 mixture of LumiGlo reagents (KPL) for 1 min, and then exposed to film. The primary antibodies used were anti-gB goat polyclonal 284 (92), anti-gC goat polyclonal 282 (92), anti-gE rabbit polyclonal (92), anti-Us9 846810 BL4 rabbit polyclonal (10), and anti-gK mouse monoclonal b7-b6-c1 (18) (provided by T. Mettenleiter, Insel Riems, Germany).

PRV mouse flank model. (i) Infections.

Mice were infected as described previously (11). Briefly, C57BL/6/J mice were depilated along the right hind flank (paravertebral fossa), and the skin was scarified after the addition of a small drop of PBS containing 105 PFU of virus. At various times postinfection, the survival of the mice and their weights were determined. At the indicated times postinfection, dorsal root ganglia (DRG), spinal cord, and skin tissue were harvested.

(ii) Preparation of tissue specimens.

Tissue specimens were placed in 10% formalin in PBS. The tissues were paraffin embedded, and 5-μm sections were generated and placed on silanated slides. The sections were deparaffinized by incubating in xylene for 5 min, rehydrated by sequential 5-min incubations in 100%, 75%, and 50% ethanol and H2O, and then washed in PBS.

Immunohistochemistry.

Sectioned, deparaffinized, and rehydrated tissue samples were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. The samples were blocked for 20 min in PBS containing 10% goat serum (Sigma) and incubated for 30 min in 200 μl of PBS containing 1% goat serum and a 1:200 dilution of anti-PRV Rb133 rabbit polyclonal antibody (7). The slides were washed three times with PBS for 5 min each, incubated for 30 min in 200 μl of PBS containing 1% goat serum and a 1:200 dilution of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (KPL), and then washed three additional times. The reaction was developed for 5 min using the commercial Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate Kit III (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), according to the manufacturer's directions, and then washed several times with water. Images were captured using a Leitz Laborlux D microscope, a Retiga 1300 digital charge-coupled-device camera (Qimaging, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) and the OpenLab v. 3.1.4 software package (Improvision, Inc., Lexington, MA).

RESULTS

Construction of the pJSΔ54 BAC.

Although many of the UL54 homologs analyzed to date are essential proteins (30, 72, 78), it was not known whether UL54 is also essential. Therefore, in order to characterize the requirements for UL54 in PRV growth and replication, the UL54 gene was deleted from the PRV genome. The UL54 allele was removed from a wild-type PRV BACmid through the use of E. coli recombination systems (1, 82, 83). Eighty percent of the 5′ end of the UL54 gene in the PRV BAC, pBecker3, was replaced with a kanamycin resistance determinant (Fig. 1C). The remaining 20% of the 3′ end of the UL54 gene was left intact for the following reasons: the UL54 transcript is 3′ coterminal with two upstream genes, UL52 and UL53 (Fig. 1B); a 500-bp repeat region of unknown function is located only 55 bp downstream of the UL54 stop codon (Fig. 1B); and the particular allele exchange system used here requires several hundred base pairs of homology to achieve efficient recombination. Therefore, leaving the 3′ end of the ORF spares both the shared poly(A) site that overlaps with the UL54 stop codon and the repeat region, while retaining a significant amount of homology to efficiently promote recombination.

Figure 2B shows that the UL54 allele is removed from the pJSΔ54 BAC, as evidenced by the absence of hybridization with a UL54 (nt 1 to 718) probe (Fig. 1B, P4). To confirm that the Δ54 allele contained the appropriate DNA arrangement, an additional Southern blot analysis was performed using a probe (Fig. 1C, P6) to the Kanr cassette flanked by the 300-bp upstream and downstream homology regions (Fig. 2C). As expected (Fig. 2A), the results show that when the DNAs are digested with BamHI, the 5′ BamHI fragment of the PRV genome shifts from ∼7.4 kb to ∼4.9 kb in the pJSΔ54 BAC and corresponding virus DNA (Fig. 2C). Replacement of the 5′ end of the UL54 gene with the Kanr cassette should also result in the loss of a SalI site (Fig. 2A). This is evidenced by the loss of the 1.9-kb SalI fragment (Fig. 2C). Thus, pJSΔ54 contained the correct allele arrangement, and this was further confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of the UL54 loci in BAC and virus DNAs. (A) Illustration of the restriction fragment length polymorphisms for BAC and virus DNAs from WT, Δ54 (pJSΔ54 and vJSΔ54), Δ54N(RK) [pJSΔ54N(RK)], and Δ54N (pJSΔ54N and vJSΔ54N). The top schematic diagram shows the relative positions of the genomic structures contained within the 5′ BamHI fragment (see the legend of Fig. 1 for key). Light gray boxes denote UL54 sequence. The thick black horizontal lines identify the 5′ BamHI fragment; sequence outside of this fragment is represented as a dotted line. The BamHI restriction sites (B) and the approximate fragment sizes (in kb; located above each diagram) are indicated in bold black type. The SalI restriction sites (S) and the relative fragment sizes (kb; located below each diagram) are identified by normal type, while the NcoI sites (N) and fragment sizes (kb) are represented in light gray type above each diagram. The Kanr, RpsL counterselectable, and neomycin selectable cassettes are shown as hatched, dark gray, or crosshatched boxes, respectively. (B to E) BAC and virus DNAs were digested with the indicated restriction enzymes and then electrophoresed through 0.8% agarose gels. The DNAs were depurinated and transferred to nylon membranes. The DNAs were hybridized to 32P-labeled (B and C) or biotinylated (D and E) DNA probes at 68°C. The membranes were washed and exposed to film (B and C) or developed using the NEB Phototope detection kit (D and E). Plasmid DNAs were used as controls. The plasmid pJSPrB5′ contains the 7.4-kb 5′ BamHI fragment from PRV, while pJSΔ54HK contains the H1 (Fig. 1)-targeted locus. The probes used were P5 (B), P6 (C), or P1 (D and E) (Fig. 1). The diagnostic 1.9-kb SalI fragment is highlighted by a black circle, while the diagnostic 1.8-, 2.4-, and 2.9-kb NcoI fragments are indicated by the arrowhead, arrow, and asterisk, respectively.

UL54 is not essential, but has a small-plaque phenotype that can be complemented in trans.

If UL54 is essential, pJSΔ54 would be unable to generate virus after transfection into Vero cells. However, virus was recovered, suggesting that the UL54 gene and its product are not essential for PRV growth and replication in tissue culture. To ensure that the Δ54 mutation was present, viral DNA was harvested from infected cells and analyzed by Southern blot analysis. The vJSΔ54 DNA contained the expected size bands (Fig. 2) consistent with the retention of the Δ54 deletion.

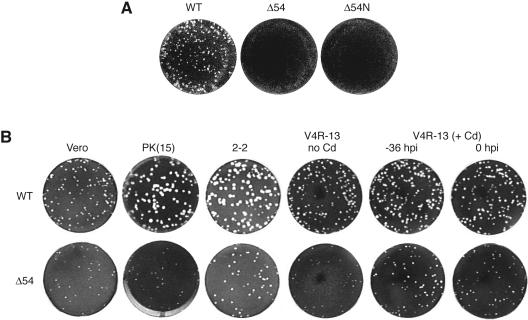

Although vJSΔ54 is viable, plaques appear 2 to 3 days later than WT virus. Plaque assays were performed (Fig. 3A), and plaque sizes were measured (Table 1). When vJSΔ54 is grown on Vero cells, the plaques are approximately half the size of WT virus (Fig. 3B and Table 1). However, on PK(15) cells, the growth defect is more severe, resulting in an approximately fourfold reduction in plaque size (Table 1 and Fig. 3B). This phenotype reverts to WT when the UL54 allele is repaired (vJSΔ54R) (data not shown), demonstrating that the small-plaque phenotype results from the Δ54 deletion.

FIG. 3.

Plaque formation and complementation by ICP27 and ORF4. WT, vJSΔ54 (Δ54), and vJSΔ54N (Δ54N) viruses were used to infect PK(15) cells (A) or the indicated cell lines (B). V4R-13 cells were treated with CdCl2 (Cd) at 36 h or simultaneously with (0 h) infection. Infections were allowed to proceed for 3 (A) or 5 (B) days. The cells were fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet, and the plates were photographed.

TABLE 1.

Quantitation of vJSΔ54 plaque sizes on complementing and noncomplementing cell lines

| Cell line | Avg plaque size (in.)a

|

Decrease (n-fold)b | Increase (n-fold)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Δ54 | |||

| PK(15) | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 3.5 | |

| Vero | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 1.7 | |

| 2-2 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| V4R-13d | ||||

| None | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 2.2 | |

| −36 hpi | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| 0 hpi | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 1.9 | |

The average plaque size and relative change (n-fold) were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Decrease (n-fold) in the average size of Δ54 plaques compared to WT on the same cell line.

Increase (n-fold) in the average size of Δ54 plaques on the indicated complementing cell line compared to Δ54 on the non-complemented Vero cell line.

V4R-13 cells were incubated with or without Cd at the indicated time postinfection.

When vJSΔ54 is grown on 2-2 cells, the plaques are the same size as WT virus grown on Vero cells (Table 1 and Fig. 3B). Thus, HSV-1 ICP27 can complement the small-plaque phenotype of the mutant UL54 virus though the converse is not true. The UL54 gene product was unable to restore the growth defect of vBSΔ27 (J. Boyer, J. Schwartz, and S. Silverstein, unpublished results), a HSV-1 mutant with a deletion of the ICP27 gene (86).

When vJSΔ54 is grown on V4R-13 cells (56), the plaque sizes are similar to those of vJSΔ54 on Vero cells (Fig. 3B and Table 1). However, if VZV ORF4 expression is induced with Cd2+, either for 36 h prior to infection or simultaneously with infection, vJSΔ54 plaque size is restored to that of WT on Vero cells (Table 1 and Fig. 3B). Western blot analysis confirms that under these conditions ORF4p accumulates after Cd2+ induction in V4R-13 cells (data not shown). Thus, both ORF4p and ICP27 complement the slow growth, small-plaque phenotype of the vJSΔ54 deletion virus.

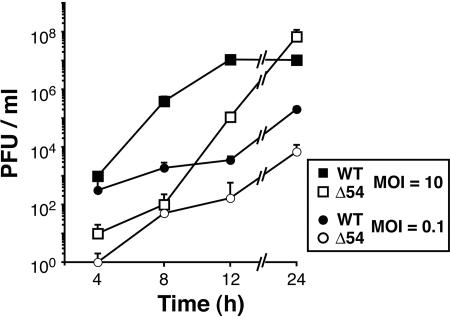

To examine the basis for the small-plaque phenotype of vJSΔ54, the kinetics of mutant virus growth were determined. As seen in Fig. 4, vJSΔ54 lags behind WT at early times postinfection at high MOIs, but by 24 hpi produces WT levels of virus. However, when infected at low MOIs, vJSΔ54 consistently yields 1 to 2 logs less virus than WT (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results demonstrate that UL54 is not essential for PRV growth but that the small-plaque phenotype of the vJSΔ54 mutant can still be complemented.

FIG. 4.

Growth kinetics of WT and vJSΔ54 viruses. PK(15) cells were infected with WT or vJSΔ54 (Δ54) at an MOI of 10 or 0.1. The infections were halted at various times postinfection by freezing, and then the cells were freeze-thawed three times to release virus. Virus yields were titrated on PK(15) cells. Each time point was performed in triplicate and titrated in duplicate. The data represent the average number of PFU/ml.

Construction of the UL54-null BAC, pJSΔ54N, using the λRed system.

Initially, vJSΔ54 was constructed to preserve the 3′ 252 bp of the UL54 gene (Fig. 1C). This was necessary to conform to the requirements of the allele exchange system used and to maintain the shared UL54 poly(A) site and the downstream repeat region (Fig. 1B). However, based on the orientation of the Kanr cassette, it was possible for the remaining portion of the UL54 gene in vJSΔ54 to generate a truncated gene product. This was of concern because the C-terminal portion of the UL54 homologs is the most highly conserved region, and it encodes many essential functional domains (9, 33, 51, 67-69, 85). Thus, the conclusions based on the vJSΔ54 virus might have been compromised by the presence of a small portion of the C terminus of the UL54 protein. Therefore, a true UL54-null virus was generated to ascertain if UL54 is essential for PRV growth.

The λRed recombination system refined by Court was chosen (15) for construction of a UL54-null virus for several reasons. First, it requires as little as 30 bp of homology to promote allele exchange (90). Second, recombination is highly efficient and precise. Third, the λRed genes can be supplied either through integration in the E. coli chromosome or from a plasmid (15, 16).

Southern blot analysis of pJSΔ54N(RK) BAC DNA shows the correct restriction fragment pattern for targeting of RpsL-Neo to the UL54 allele (Fig. 2). As expected, insertion of the RpsL-Neo cassette resulted in the loss of SalI and NcoI sites (Fig. 2A), as evidenced by the loss of the 1.9-kb SalI and the 4-kb NcoI fragments, respectively (Fig. 2D). The RpsL-Neo insertion also generates new NcoI sites (Fig. 2A), which results in two new fragments of 2.4 and 1.8 kb (Fig. 2D).

The pJSΔ54N(RK) BAC has all but the last 21 bp of the UL54 ORF removed. To remove additional UL54 sequence and the RpsL-Neo genes, a second recombination (“loop-out”) step was performed. The downstream homology region only overlaps with the last 11 bp of the UL54 gene, including the stop codon (Fig. 1D, H3). Counterselection using the RpsL gene resulted in (1 out of 400 remained Kanr) generation of the UL54-null BAC, pJSΔ54N (note that only 30% of the Strr BACs contained the appropriate restriction fragment pattern). The loop-out results in a 1-kb loss in the size of the 5′ BamHI fragment (Fig. 2E), and the 2.4- and 1.8-kb NcoI fragments generated by the RpsL-Neo insertion are no longer present in the pJSΔ54N DNA (Fig. 2E).

The vJSΔ54N virus is viable and exhibits a small-plaque phenotype.

Although the vJSΔ54 virus was viable, it was not clear whether vJSΔ54N would also be viable. After transfection of the pJSΔ54N DNA into Vero cells, virus was recovered. The arrangement of the vJSΔ54N null allele was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2). Like vJSΔ54, vJSΔ54N had a slow growth phenotype, which yielded small plaques (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that the original Δ54 deletion in vJSΔ54 probably acts as a null mutation.

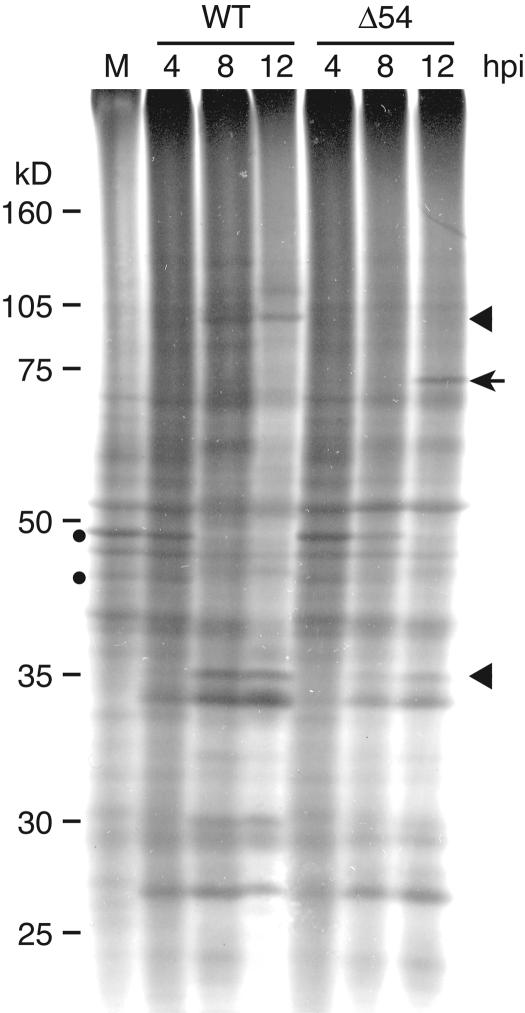

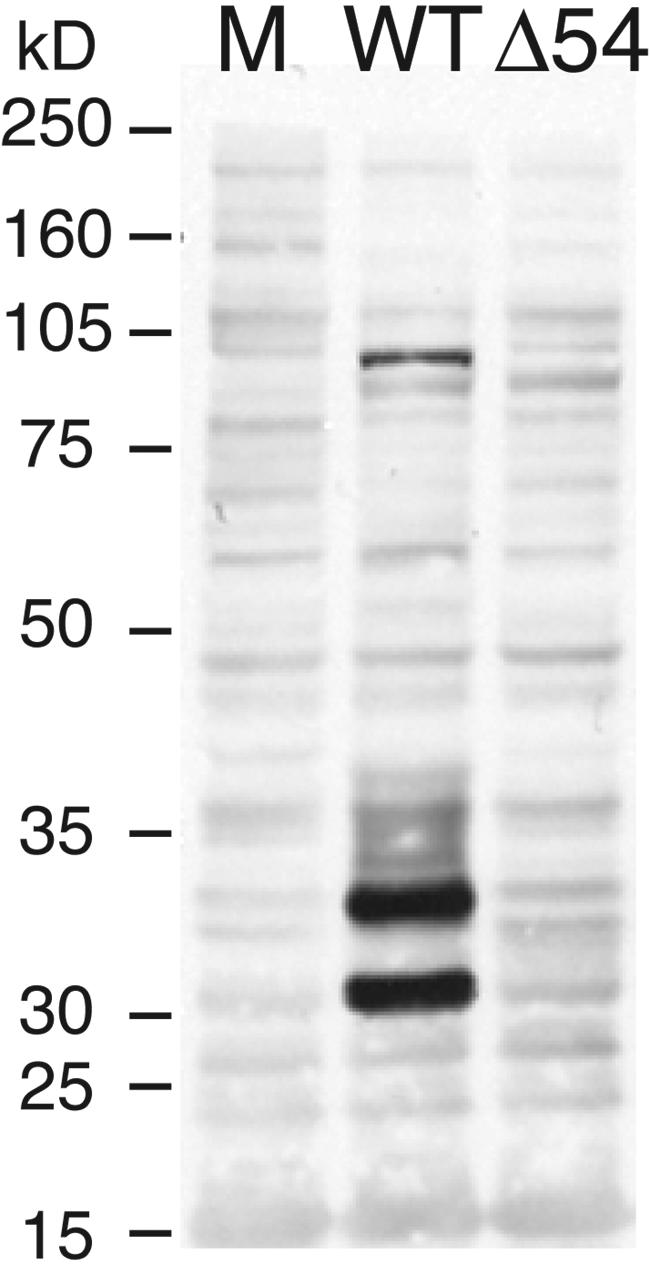

UL54 is not essential for host shut-off.

Unlike other ICP27 homologs (30, 72, 78), UL54 is not essential, but because of the highly conserved nature of these proteins, it may possess many of the same functions as its homologs. To determine if UL54, like ICP27 (32, 34), plays a role in the shut-off of host cell protein synthesis, infected cells were metabolically labeled with 35S, and the protein profiles were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. vJSΔ54-infected cells shut off host protein synthesis as efficiently as WT virus in RK13 (Fig. 5, circles) and PK(15) (data not shown) cells. The protein profile was altered at late times postinfection in vJSΔ54-infected cells compared to WT (Fig. 5). Several proteins are present at late times postinfection that are absent in the WT-infected cell extracts (Fig. 5, arrow). Additionally, there are proteins present in the WT-infected cells at 12 hpi whose levels are reduced at the same time point in the vJSΔ54-infected cells (Fig. 5, arrowheads). Similar aberrant protein profiles were also observed in PK(15)-infected cell extracts (data not shown); however, no apparent differences could be observed between the infected cell protein profiles of WT and vJSΔ54 on Vero or 2-2 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Shut-off of host protein synthesis in PRV-infected cells. RK13 cells were mock infected (M) or infected with WT or vJSΔ54 (Δ54) virus at a MOI of 5. At 4, 8, and 12 hpi, the infected cells were metabolically labeled with 35S for 30 min. Whole-cell extracts were prepared and electrophoresed through a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The gel was then dried and exposed to film. The filled circles identify host proteins with reduced accumulation over time in infected cells. The arrow and arrowhead identify proteins whose accumulation is aberrant (either increased or decreased, respectively) in cells infected with Δ54.

UL54 functions in gene regulation.

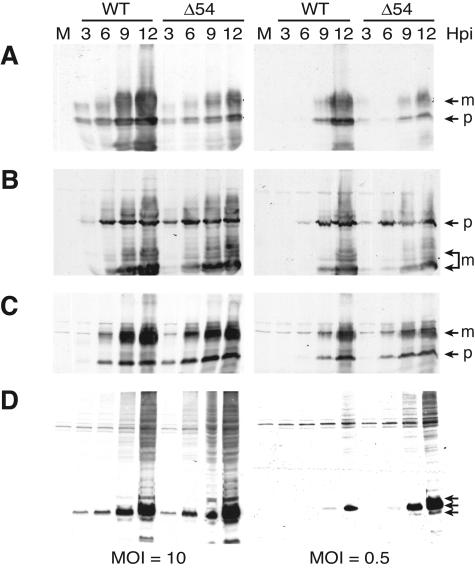

ICP27 regulates the expression of virus genes at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level (22, 23, 26, 27, 47, 51, 60, 61, 66, 67, 72, 81). Specifically, ICP27 mutants have been shown to alter the kinetics of late gene expression. To determine whether UL54 has a similar role, accumulation of late proteins was analyzed by Western blot analysis in vJSΔ54-infected PK(15) cells. While the kinetics are the same as WT, accumulation of the glycoprotein gC is decreased in cells infected with vJSΔ54 (Fig. 6A). This is observed at both high (Fig. 6A, left panel) and low (Fig. 6A, right panel) MOIs. This result is consistent with what occurs with ICP27 mutants (40, 84). The accumulation of other late gene products was analyzed. Unlike the effect on gC accumulation, the kinetics of accumulation of the glycoproteins gB (Fig. 6B) and gE (Fig. 6C) and the membrane protein Us9 (Fig. 6D) are similar in cells infected with vJSΔ54 and WT. However, each of these proteins is more abundant in cells infected with the mutant virus at earlier times postinfection. For gB and gE, this phenotype is seen at both high and low MOIs (Fig. 6B and C, respectively). However, the aberrant accumulation of Us9 is only observed at low MOIs (Fig. 6D). These effects on gene expression appear to be cell type specific, as no dramatic difference in accumulation of these late proteins was observed in Vero, 2-2, and V4R-13 cells infected with WT or vJSΔ54 virus (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Accumulation of late proteins after infection with vJSΔ54. PK(15) cells were either mock infected (M) or infected at a MOI of 10 or 0.5. At 3, 6, 9, and 12 hpi, whole-cell extracts were prepared and subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE. Protein accumulation was determined by Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for gC (A), gB (B), gE (C), or Us9 (D). The different glycoprotein isoforms (m, mature; p, precursor) are indicated by the arrows.

vJSΔ54 is highly attenuated in a mouse model of PRV infection.

PRV is able to infect all mammals except higher-order primates, and it is 100% lethal in all hosts except adult pigs (96). Many animals have been infected with PRV in the laboratory (96); however, the majority of these studies use PRV as a neurotropic tool to examine mammalian neural circuits rather than to study PRV pathogenesis and biology (21). To this end, the mouse flank model of PRV infection was developed to study PRV pathogenesis (11).

To examine the effect of deletion of UL54 on pathogenesis of the vJSΔ54 virus, mice were infected, and analyses of survival and weight loss were performed. As expected, infection by both WT and vJSΔ54 is 100% lethal in this mouse model (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, mice infected with vJSΔ54 survive at least twice as long as those infected with WT virus (Fig. 7A). This attenuation corresponded to a 35-h delay in the onset of symptoms (e.g., pruritus and self-mutilation). By 51 h severe pruritus was present. The prolonged survival of vJSΔ54-infected mice, along with the delayed onset of pruritus, resulted in an extended time of self-induced trauma. Similar to symptoms seen in adult pigs (96), mice infected with WT PRV exhibit rapid weight loss (Fig. 7B). Mice infected with vJSΔ54 tend to lose weight more slowly than animals infected with WT virus (Fig. 7B); however, weight loss does not appear to correlate with mortality as at the ∼50% survival point mice infected with WT or vJSΔ54 virus have similar degrees of weight loss (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Pathogenesis of vJSΔ54 in a mouse flank scarification model: survival and wasting phenotypes. Mice were infected as previously described (11). Briefly, mice were depilated along the right hind flank (paravertebral fossa), and the skin was scarified after the addition of a small drop of PBS containing 105 PFU of WT (squares) or vJSΔ54 (circles) virus. (A) Survival was monitored every 6 h and plotted as percent survival. (B) Mice mock infected (triangles) or infected with WT (squares) or vJSΔ54 (circles) virus were weighed every 24 h. Data points represent the average weight in grams for the mice surviving at each time point.

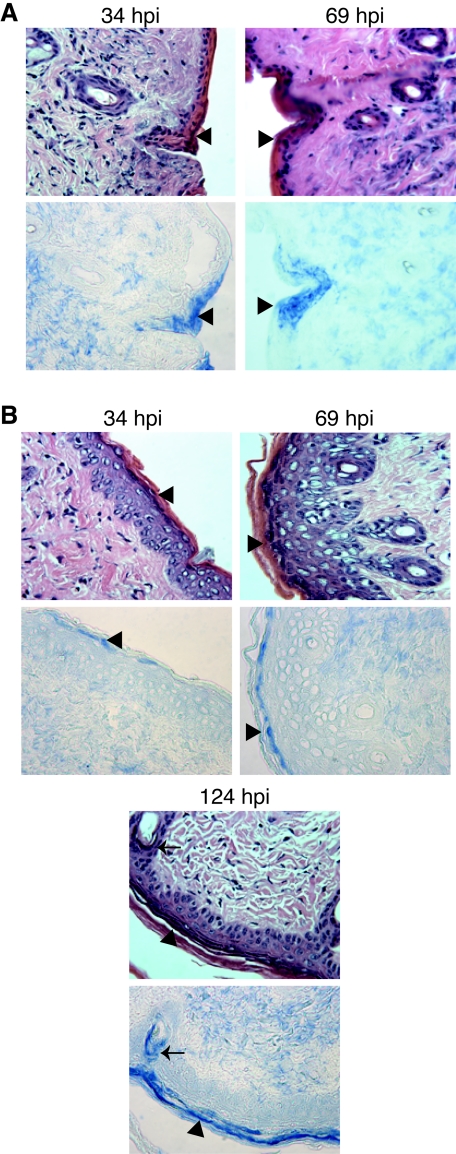

Because mice infected with vJSΔ54 survive for extended periods of time, the distribution of virus within the mouse tissues was analyzed by immunohistochemistry over the course of the infection. WT virus antigens were observed in the epidermis and, to a lesser extent, the dermis at 34 hpi (Fig. 8A). By 69 hpi, WT virus antigens accumulate in the epidermis (Fig. 8A, arrowheads), dermis (Fig. 8A), hair follicles (Fig. 8A), and, to a lesser extent, in the underlying fatty layer (data not shown). Interestingly, by 69 hpi a significant amount of lymphocytic infiltrate is observed in the skin (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Distribution of PRV antigens in infected mouse skin tissue. Mice were infected with WT (A) or vJSΔ54 (B) virus as described in the legend of Fig. 7. At 34, 69, or 124 hpi, mice were euthanized, and skin adjacent to the inoculation site was dissected and fixed in 10% formalin. The tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 1-μm serial sections were collected. The sections were deparaffinized and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. One serial section (top row) was counterstained with H&E, while the adjacent section (bottom row) was stained with the rabbit polyclonal antibody Rb133 (7), specific for whole PRV. Anti-PRV antibody was visualized with secondary antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and reacted to a blue substrate. Images were obtained with a 40× objective using a Leitz Laborlux microscope. The arrow identifies a hair follicle stained for PRV antigens, whereas the arrowheads identify epidermal cells containing PRV.

The distribution of viral antigens in the skin of mice infected with vJSΔ54 was also examined. At 34 hpi, only small amounts of viral antigens were detected in the skin sections, although some did appear in the epidermis (Fig. 8B). However, a significant amount of antigen was observed in both the epidermis and dermis at 69 hpi (Fig. 8B). By very late times postinfection (124 hpi), vJSΔ54 antigens are present in the fatty layer (data not shown) as well as the dermis and epidermis (Fig. 8B). This time point was not available for animals infected with WT virus as they were dead by 124 hpi. As observed with WT virus, a lymphocytic infiltrate accumulates in the skin, although not until 124 hpi (data not shown). Thus, while infection with vJSΔ54 appears to result in a similar distribution of antigen within the skin compared to WT, its appearance in the various layers of the skin is delayed (compare Fig. 8A and B).

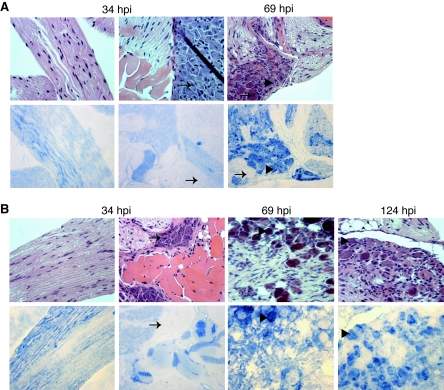

To determine whether the appearance of vJSΔ54 antigens is delayed compared to WT in the DRG, infected DRGs were dissected and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. By 34 hpi, WT virus antigen staining is observed in nerve fibers (Fig. 9A, left panel) and in some muscle tissue (Fig. 9A, middle panel) that accompanied the dissection of the DRG from the spinal column but not in the neural cell bodies of the DRG (Fig. 9A, arrows). However, by 69 hpi, a significant amount of WT virus antigen is found in the cell bodies of neurons (Fig. 9A, arrowheads) and satellite cells (Fig. 9A). Unlike what is observed in the skin, vJSΔ54 virus antigen accumulation can be observed in nerve fibers (Fig. 9B, left panel) and DRG-associated muscle fibers (Fig. 9B) by 34 hpi. It is not apparent why this difference exists, but it might reflect a difference in replication kinetics in the two tissues. By 69 and 124 hpi, vJSΔ54 virus antigens are present in neurons and possibly satellite cells (Fig. 9B, arrowheads).

FIG. 9.

Distribution of PRV antigens in infected mouse DRGs. Mice were infected with WT (A) or vJSΔ54 (B) virus as described in the legend of Fig. 7. At 34, 69, or 124 hpi, mice were euthanized, and DRGs innervating the inoculation site dermatomes were dissected. The tissues were fixed, embedded, sectioned, and subjected to H&E staining or immunohistochemical analysis as described in the legend of Fig. 8. The leftmost panels represent nerve fiber associated with the dissected DRGs harvested at 34 hpi. The arrows indicate neurons that do not contain PRV antigens, while the arrowheads identify those that do contain PRV.

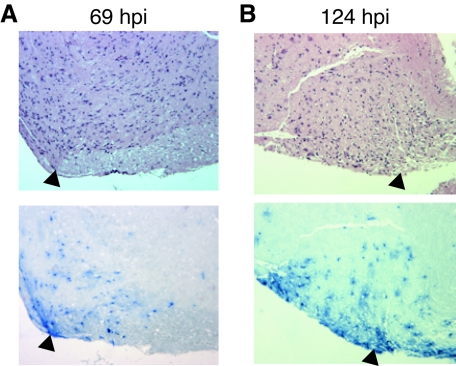

Spinal cord tissue was also examined for the presence of viral antigens. At 34 hpi, no WT virus antigen was detected in spinal cord neurons, but it was found in muscle fibers associated with the spinal column (data not shown). It was not until 69 hpi that WT virus antigens were detected in spinal cord neurons (Fig. 10A, arrowheads). Similar to the observations of skin from animals infected with vJSΔ54, the appearance of viral antigens in spinal cord neurons is delayed (Fig. 10B). While vJSΔ54 antigens are found in spinal muscle (data not shown), positive staining does not occur in the spinal cord until 124 hpi (Fig. 10B, arrowheads).

FIG. 10.

Distribution of PRV antigens in infected mouse spinal cord tissues. Mice were infected with WT (A) or vJSΔ54 (B) virus as described in the legend of Fig. 7. At 34, 69, or 124 hpi, mice were euthanized, and the spinal cords adjacent to the inoculation site dermatomes were dissected. The tissues were fixed, embedded, sectioned, and subjected to H&E staining or immunohistochemical analysis as described in the legend of Fig. 8. The arrowheads identify neurons that positively stain for PRV antigens.

DNA replication is reduced in cells infected with vJSΔ54.

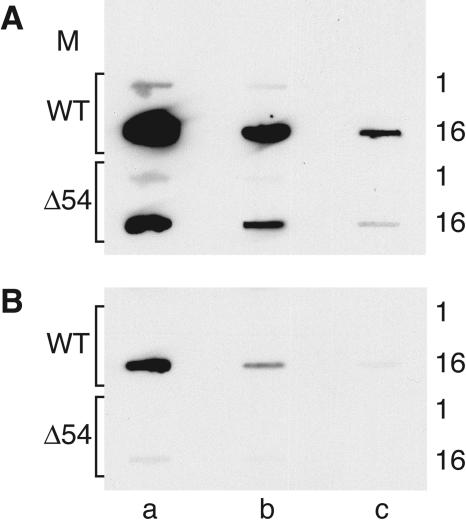

Because the UL54 transcript is 3′ coterminal with its two upstream neighbors (UL52 and UL53) (5), it is important to determine if the insertion affects the expression of UL52 and/or UL53. We analyzed UL52 protein expression in cells infected with vJSΔ54. UL52 is a subunit of the helicase-primase complex and is essential for viral replication (41). Based on UL52's essential nature and the ability to recover viable vJSΔ54 virus in the absence of complementation, it is likely that UL52 protein is present and functional. Unfortunately, antibodies against PRV UL52 are not available, so DNA replication assays were used to indirectly assay for functional UL52. Both PK(15) (Fig. 11) and Vero (data not shown) cells infected with vJSΔ54 were able to replicate PRV DNA at high (Fig. 11A) and low (Fig. 11B) MOIs although at reduced levels compared to WT virus (Fig. 11). The replication defect in Vero cells (data not shown) is not as dramatic as that observed in PK(15) cells (Fig. 11), which is consistent with the plaque assay results (Fig. 3B) where both WT and vJSΔ54 grow more slowly on Vero cells.

FIG. 11.

Analysis of DNA replication in infected PK(15) cells. PK(15) cells were mock infected (M) or infected with WT or vJSΔ54 (Δ54) at a MOI of 10 (A) or 0.01 (B). Total infected cell DNAs were harvested at 1 or 16 hpi and denatured, and serial 10-fold dilutions were slot-blotted onto a nylon membrane. Lane a represents 1.5 × 105 cell equivalents of total cell DNA; lanes b and c contain 10−1 and 10−2 dilutions, respectively. Viral DNA was detected by hybridization with the biotinylated DNA probe, P1 (Fig. 1). Biotinylated DNA was visualized using a NEB Phototope kit as described in Materials and Methods.

Glycoprotein K level is undetectable in vJSΔ54-infected cells.

The levels of the UL53 gene product, glycoprotein K (gK), were assessed by Western blot and immunofluorescence assays. Western blot analysis demonstrates that gK is present in both mature and precursor forms at 24 hpi in extracts prepared from PK(15) cells infected with WT virus but is apparently absent from cells infected with vJSΔ54 (Fig. 12) or vJSΔ54N (data not shown) virus. In contrast, accumulation of gB is unaffected (data not shown). To confirm these results, cells infected with vJSΔ54 were examined for gK by indirect immunofluorescence; this analysis revealed no apparent staining (data not shown). Glycoprotein K was previously shown to be an important, but not necessarily essential, protein for replication of PRV (42). Therefore, like the UL52 protein, gK must be expressed in amounts that are sufficient for vJSΔ54 virus viability and spread but that are below the level of detection by the Western blot (Fig. 12) and immunofluorescence (data not shown) assays used here.

FIG. 12.

Western blot analysis of the accumulation of the UL53 gene product, gK. PK(15) cells were mock infected (M) or infected at a MOI of 10 with WT or vJSΔ54 (Δ54). At 24 hpi, whole-cell extracts were harvested in NET-2 lysis buffer and sonicated. Aliquots of each extract were incubated at 37°C for 30 min prior to SDS-PAGE analysis. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and visualized by Western blot analysis with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific to gK.

UL52 and UL53 RNAs are expressed in vJSΔ54- and vJSΔ54N-infected cells.

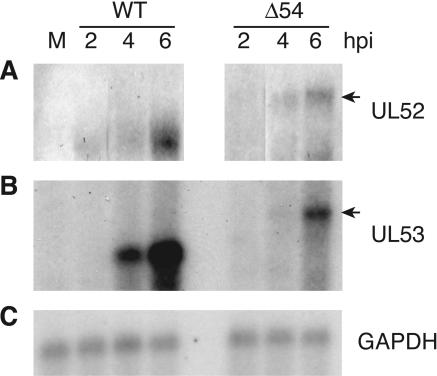

It was not clear from the previous results whether the reduction in UL53, and possibly UL52, proteins in cells infected with the mutant virus occurs at the posttranscriptional and/or transcriptional level. Therefore, Northern blot analysis was performed on total RNA isolated from infected PK(15) cells. The ∼5.6-kb WT UL52 RNA can be visualized as early as 2 hpi and accumulates to ∼10 times higher levels by 6 hpi in cells infected with WT virus compared to vJSΔ54 virus (Fig. 13A). The WT UL53 RNA, which is ∼2.8 kb, is not detectable until approximately 4 hpi (Fig. 13B). As with UL52, the kinetics of UL53 RNA accumulation are the same for cells infected with WT or vJSΔ54 (Fig. 13B) virus. However, accumulation of UL53 RNA in cells infected with vJSΔ54 is ∼50% of that which accumulates in cells infected by WT virus (Fig. 13B). Insertion of the Kanr cassette into the UL54 allele of vJSΔ54 should increase the size of the UL52 and UL53 RNAs by approximately 500 bp. Indeed, both the UL52 and UL53 RNAs are present at the expected sizes (Fig. 13A and B, arrows, respectively). Although, the accumulation of these RNAs in cells infected with vJSΔ54 is reduced in comparison to accumulation after infection with WT virus, the kinetics of expression are apparently unchanged (Fig. 13). Similar results are seen for RNAs from cells infected with vJSΔ54N (data not shown).

FIG. 13.

Northern blot analysis of the UL52 and UL53 transcripts. PK(15) cells were mock infected (M) or infected with WT or vJSΔ54 (Δ54) at a MOI of 10. At 2, 4, or 6 hpi, total RNA was harvested. Five micrograms of RNA was electrophoresed through a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel. The RNAs were partially hydrolyzed and then transferred to a nylon membrane. The filters were hybridized to 32P-labeled DNA probes as described in Materials and Methods. The membranes were washed and then exposed to film. The DNA probes were random primed from PCR products generated to the UL52 (A) (Fig. 1B, P3), UL53 (B) (Fig. 1B, P4), and porcine GAPDH (C) ORFs. The arrows identify the UL52 (A) and UL53 (B) RNAs from vJSΔ54.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe the construction of PRV mutants at the UL54 locus (Fig. 1 and 2), through the use of recombineering technology in E. coli, and the characterization of these mutants in tissue culture and mice. We show that UL54 is not essential for PRV growth in tissue culture (Fig. 3) but that deletion mutants exhibit reduced virus yields and plaque sizes (Fig. 3 and Table 1), aberrant accumulation of virus proteins (Fig. 5, 6, and 12), and a highly attenuated phenotype in a mouse model of PRV infection (Fig. 7).

To determine the requirements for UL54 in PRV growth and replication, it was first necessary to construct a virus with a deletion of this gene. Allele exchange in E. coli was first used by utilizing selectable markers and a sugar suicide system to replace the majority of the UL54 allele from the PRV BAC, pBecker3, with a Kanr cassette (Fig. 1C). Originally, only the first 80% of the UL54 ORF was removed. In our hands, use of this sugar suicide system required at least 300 bp of homology on either side of this locus to promote allele exchange with the targeted Kanr UL54 cassette (Fig. 1C, H1). Despite the use of selectable and counterselectable markers, the efficiency of recombination was only 0.1%. Screening for targeted events by PCR was hampered by the high G+C content (75%) of PRV. Therefore, in addition to PCR analysis (data not shown), dot (data not shown) and Southern (Fig. 2) blot analyses were used to identify a BAC containing the Δ54 locus (Fig. 1C, H1). Using restriction enzyme mapping, we confirmed that the arrangement of the Δ54 locus was correct (Fig. 2B and C).

In order to ascertain whether UL54 is essential for PRV growth, the Δ54 BAC DNA, pJSΔ54, was transfected into Vero cells. Virus (vJSΔ54) was recovered from these transfections, thus demonstrating that UL54 is not essential for PRV growth in tissue culture. We observed, however, that it took several days longer for vJSΔ54 plaques to appear compared to WT virus (Fig. 3B). Analysis of the growth kinetics of this mutant demonstrated that at high MOIs it lags behind WT but is able to recover to WT levels by late times postinfection (Fig. 4). However, at low MOIs the yield of vJSΔ54 is less than WT at all time points examined (Fig. 4). Furthermore, we observed that the growth defect of vJSΔ54 was partially cell type specific as the severity of the defect was reduced on Vero cells compared to PK(15) cells (Fig. 3B). The severity of this defect is not likely a direct result of the vJSΔ54 mutation but, rather, a result from the overall reduced plaquing efficiency of the WT PRV Becker strain on Vero compared to PK(15) cells (Fig. 3B). However, cell type-specific effects might explain the delay in appearance of vJSΔ54 antigens in infected mouse tissues (Fig. 8, 9, and 10). When the deletion mutant was repaired, we found that the kinetics of plaque formation and plaque size were restored to WT levels (data not shown), thus confirming that the molecular basis for the phenotype correlates with the deletion of UL54.

Due to practical limitations, the pJSΔ54 BAC and corresponding virus, vJSΔ54, had a deletion of only the first ∼80% of the UL54 ORF. The replacement cassette has potential initiating methionines that could result in an N-terminally-truncated form of the UL54 protein. This was of concern as the C-terminal portion of UL54 is the most highly conserved region and, based on studies with UL54 homologs, possesses many essential functional domains. Therefore, using the λRed system for allele exchange, we constructed a complete null allele of UL54 in both BAC and virus DNA, pJSΔ54N and vJSΔ54N, respectively (Fig. 1 and 2). We found no significant difference in phenotypes between these viruses (Fig. 3), suggesting that the deletion in vJSΔ54 functions as a true null mutation.

We were also interested to learn whether other alphaherpesvirus homologs of UL54 were able to complement the slow-growth defect of vJSΔ54. Therefore, we utilized stably transformed cell lines to grow vJSΔ54 in the presence of the HSV homolog, ICP27, or the VZV homolog, ORF4. Both ICP27 and ORF4 were able to restore the plaque size of vJSΔ54 to WT levels compared to vJSΔ54 virus grown on Vero cells (Fig. 3B and Table 1), and they were also able to enhance the plaque sizes of WT on the complementing cell lines (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Thus, ICP27 and ORF4 can complement some of the functions of UL54 in a PRV infection system.

The ability of ICP27 to complement a deletion of UL54 in PRV, but not vice versa, suggests that ICP27 shares one or more functions with UL54. However, that ICP27 is essential for virus growth while UL54 is not and that UL54 cannot functionally substitute for ICP27 in vBSΔ27, an HSV-1 mutant with a deletion of ICP27 (86) (J. Boyer, J. Schwartz, and S. Silverstein, unpublished results), imply that either UL54 lacks one of the essential ICP27 function(s) or that PRV possesses another protein that provides this activity. At this time, no functions have been ascribed to UL54. ICP27 functions, on the other hand, have been well studied. ICP27 is a multifunctional protein that acts at the transcriptional (33, 40, 48, 51, 89, 93) and posttranscriptional levels (12, 48-50, 52, 57, 74, 86) to regulate host and virus gene expression. ICP27 aids in the shut-off of host cell protein synthesis (32, 34) through its ability to prevent host RNA splicing (74). ICP27 also regulates translation of at least one virus-specified mRNA (20, 25). To this end, we assayed the ability of vJSΔ54 to shut off the synthesis of host proteins in infected cells. Deletion of UL54 does not appear to inhibit the ability of the virus to shut down host protein synthesis (Fig. 5).

As stated earlier, HSV-1 ICP27 affects the expression of E and L gene products (47, 62, 72, 73, 84). We observed that the viral protein profile appeared to be altered in metabolically labeled vJSΔ54-infected RK13 cells (Fig. 5) and PK(15) cells (data not shown). Therefore, we examined the accumulation of several L proteins in cells infected with vJSΔ54. As seen with ICP27 (40), UL54 appears to positively regulate expression of the glycoprotein gC, as accumulation of gC is lower in PK(15) cells infected with vJSΔ54 than in cells infected with WT virus (Fig. 6A). It is, however, unclear if this regulation occurs at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level and if there is a direct effect on gC expression or an indirect effect due to a downstream effect on a regulatory protein(s) by UL54. Yet ICP27 from HSV (40) and bovine herpesvirus 1 (31) regulates gC at the transcriptional level. Thus, it is likely that UL54 regulates the transcription of gC and that deletion of UL54 leads to reduced transcription from the gC locus and hence less gC. It is interesting that PRV gC mutants have slow growth phenotypes due to reductions in attachment and subsequent penetration (79, 80, 94). Although these studies have only examined gC− mutants, it is possible that the reduced levels of gC produced by vJSΔ54 lead to a similar phenotype. This does not account for the attenuation of vJSΔ54 in a mouse model of infection (Fig. 7), as gC is not required for penetration or propagation of PRV in the mouse nervous system (24).

We also examined the accumulation of other L proteins in cells infected with vJSΔ54. Glycoprotein gB (Fig. 6B), gE (Fig. 6C), and Us9 (Fig. 6D) accumulated to higher levels than in cells infected with WT virus. However, there was little if any gK in extracts prepared at 24 hpi from cells infected with the mutant virus (Fig. 12). Glycoprotein gK is encoded by UL53, whose mRNA is 3′ coterminal with UL54 (Fig. 1B) (5). gK is required for virion release (18, 42) but not for neuroinvasiveness (24), and gK− viruses are able to grow, albeit with reduced kinetics and yields compared with WT. It is thus possible that the slow growth phenotype of vJSΔ54 may result from reduced levels of gK expression. Previously, it was shown that insertions into the PRV BAC could lead to polar effects on the expression of adjacent genes (82, 83). The replacement of the first 80% of the UL54 ORF in vJSΔ54 may contribute to reduced levels of gK, or UL54 may function to regulate the expression of gK. Although little if any gK is detected in cells infected with vJSΔ54 (Fig. 12) or vJSΔ54N (data not shown) by Western blotting or immunofluorescence assays (data not shown), the UL53 RNA is still present, albeit at reduced levels (Fig. 13). The ability of vJSΔ54N to accumulate UL53 RNA at levels close to vJSΔ54 (data not shown) suggests that the Kanr insertion into the UL54 locus is not the cause of the disruption in gK expression, as seen with other PRV BAC insertions (82, 83). However, the defects in plaque size and virus yields of vJSΔ54 appear to mimic those seen in gK− mutants (18, 42), suggesting that although gK levels are sufficient to support replication, the observed growth defects and possibly the in vivo attenuation may result from reduced gK. In fact, while the deletion of UL54 results in a delay in appearance of virus antigen in nervous tissues, the mutant virus is still able to retain neuroinvasive characteristics. This suggests that gK may contribute to the molecular basis of vJSΔ54 attenuation.

HSV-1 infection triggers apoptosis of infected cells (63, 95, 99). However, HSV-1 is able to then inhibit the induction of apoptosis. This inhibitory activity can occur in the absence of de novo protein synthesis (44) and is an IE event (2, 77). ICP27 has a role in the inhibition of apoptosis as ICP27 mutants do not block apoptosis (2, 3). No prior studies of PRV-induced apoptosis have been performed. Thus, it is possible that the phenotypes of the UL54 deletion mutants could be attributed to apoptosis. There was no discernible difference in chromatin condensation in Vero cells infected with WT PRV, the UL54 mutants, or the ICP27 deletion mutant, vBSΔ27 (data not shown).

In addition to induction of chromatin condensation, apoptosis causes a caspase cascade that leads to cleavage of cellular enzymes, such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (reviewed in reference 76). Because the UL54 mutant phenotypes were more pronounced in porcine cells, we examined the ability of the UL54 mutants to induce cleavage of PARP. PARP was cleaved in PK(15) cells infected with WT PRV, vJSΔ54, and vJSΔ54N and, to a lesser extent, in cells infected with vBSΔ27, while mock-infected cells showed little or no cleavage (data not shown). Although there were slight differences in PARP cleavage levels between WT PRV and the UL54 mutants, the differences were not more than twofold. Therefore, we believe that apoptosis is not a contributing factor to the small-plaque phenotype seen when PK(15) cells are infected with UL54 mutant viruses.

The UL52 RNA is also 3′ coterminal with UL54 (Fig. 1B) (5). We found that like UL53, UL52 RNA accumulation is decreased in cells infected with the mutant virus (Fig. 13A). The decreased levels of UL52 RNAs, which encode an essential primase subunit, likely contribute to the lag in replication of vJSΔ54 DNA (Fig. 11). ICP27 has a similar effect on UL52 RNA accumulation in HSV-infected cells (93). Therefore, it is likely that UL54 regulates UL52 expression at the level of transcription.

To determine whether deletion of UL54 affects the virulence of PRV, we utilized a mouse model of PRV infection (11). While infection with vJSΔ54 resulted in 100% lethality (Fig. 7A), the infected animals survived at least twice as long as WT-infected animals (Fig. 7B). Despite the attenuation, vJSΔ54-infected mice lost as much weight as those infected with WT virus (Fig. 7B). To characterize the neuroinvasiveness of vJSΔ54, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on infected skin, DRG, and spinal cord tissues (Fig. 8, 9, and 10, respectively). The appearance of antigens specific for vJSΔ54 lagged behind that seen for WT virus in skin (Fig. 8), DRG (Fig. 9), and spinal cord tissue (Fig. 10). However, vJSΔ54 antigens were present in nerve fibers associated with the DRG at the earliest time examined (Fig. 9B, leftmost panel), similar to what is seen in animals infected with WT virus (Fig. 9A, leftmost panel). It is unclear why the kinetics of antigen accumulation are not delayed in nerve fibers of animals infected with vJSΔ54.

The pathogenesis of vJSΔ54 infection in this model appears unique because, to date, it is the only virus with a single mutation where the infected mice survive past ∼125 hpi. Additionally, it is the only attenuated virus studied in this model that did not reduce the severity of pruritic symptoms or lesions. In fact, lesion severity was exacerbated since mice infected with vJSΔ54 scratch for 50 h longer than those infected with WT virus. One mutant virus, the Bartha vaccine strain, is more highly attenuated than vJSΔ54 in this system (11). However, Bartha contains multiple mutations and the molecular basis for its attenuation is unknown (4, 43, 46, 55, 64, 70). Interestingly, while Bartha has reduced virulence, infected animals do not exhibit pruritus or self-induced trauma but do show signs of neurological abnormalities (11). Once animals infected with vJSΔ54 show evidence of disease, the resulting peripheral neuropathy closely resembles what occurs in animals infected with WT virus, and no signs of neurological abnormalities are evident. While the kinetics of accumulation are unchanged, accumulation of gE and Us9, two factors that have been implicated in the manifestation of pruritus and dermatomal lesions (11), is increased in vJSΔ54-infected cells (Fig. 6). Viruses with deletions of either of these loci are not as attenuated as vJSΔ54 (11).

The nature of the single known mutation of vJSΔ54 and its remarkable in vivo attenuation may have implications for vaccine development. The delay in symptoms and spread of virus antigens to the nervous system make vJSΔ54 an attractive starting point for development of a live vaccine. The lingering nature of this mutant and its retention of expression of many of the immunogenic viral glycoproteins might enhance the immune response to PRV. The immunogenicity of recombinant viruses bearing a UL54 null mutation combined with other known attenuating mutations (e.g., tk or gE) found in standard live vaccines should be examined.

The evidence provided here shows that UL54 is not essential for PRV growth in tissue culture but that it contributes to virulence in a mouse model and suggests roles for UL54 in the transcriptional regulation of E and L genes. However, the severity of the mutant phenotypes is cell type specific as evidenced by reduced plaquing efficiency and an apparent lack of an aberrant gene expression profile in infected Vero cells compared to PK(15) cells. Our results suggest that UL54 does not appear to possess known posttranscriptional functions, as shut-off of host protein synthesis appears unaltered in the UL54 deletion mutants. However, based on the highly conserved C terminus of UL54 with its other homologs (9), this requires further investigation. PRV may possess unknown redundant functions, and further exploration is needed to ultimately conclude that there is no role for UL54 at the posttranscriptional level.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Greg Smith for his advice and help with the PRV BACmid system.

This study was supported in part by grants from the Public Health Service AI-33952 (S.J.S.) and NINDS-1RO1 33506 (L.E.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., M. Messerle, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2003. Cloning of herpesviral genomes as bacterial artificial chromosomes. Rev. Med. Virol. 13:111-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubert, M., and J. A. Blaho. 1999. The herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP27 is required for the prevention of apoptosis in infected human cells. J. Virol. 73:2803-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubert, M., and J. A. Blaho. 2001. Modulation of apoptosis during herpes simplex virus infection in human cells. Microbes Infect. 3:859-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartha, A. 1961. Experimental reduction of virulence of Aujeszky's disease virus. Mag. Allat. Lap. 16:42-45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumeister, J., B. G. Klupp, and T. C. Mettenleiter. 1995. Pseudorabies virus and equine herpesvirus 1 share a nonessential gene which is absent in other herpesviruses and located adjacent to a highly conserved gene cluster. J. Virol. 69:5560-5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bello, L. J., A. J. Davison, M. A. Glenn, A. Whitehouse, N. Rethmeier, T. F. Schulz, and J. Barklie Clements. 1999. The human herpesvirus-8 ORF 57 gene and its properties. J. Gen. Virol. 80:3207-3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billig, I., J. M. Foris, L. W. Enquist, J. P. Card, and B. J. Yates. 2000. Definition of neuronal circuitry controlling the activity of phrenic and abdominal motoneurons in the ferret using recombinant strains of pseudorabies virus. J. Neurosci. 20:7446-7454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldogkoi, Z., A. Sik, A. Denes, A. Reichart, J. Toldi, I. Gerendai, K. J. Kovacs, and M. Palkovits. 2004. Novel tracing paradigms—genetically engineered herpesviruses as tools for mapping functional circuits within the CNS: present status and future prospects. Prog. Neurobiol. 72:417-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer, J. L., S. Swaminathan, and S. J. Silverstein. 2002. The Epstein-Barr virus SM protein is functionally similar to ICP27 from herpes simplex virus in viral infections. J. Virol. 76:9420-9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brideau, A. D., B. W. Banfield, and L. W. Enquist. 1998. The Us9 gene product of pseudorabies virus, an alphaherpesvirus, is a phosphorylated, tail-anchored type II membrane protein. J. Virol. 72:4560-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brittle, E. E., A. E. Reynolds, and L. W. Enquist. 2004. Two modes of pseudorabies virus neuroinvasion and lethality in mice. J. Virol. 78:12951-12963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, C. R., M. S. Nakamura, J. D. Mosca, G. S. Hayward, S. E. Straus, and L. P. Perera. 1995. Herpes simplex virus trans-regulatory protein ICP27 stabilizes and binds to 3′ ends of labile mRNA. J. Virol. 69:7187-7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chee, M. S., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Horsnell, C. A. Hutchison III, T. Kouzarides, J. A. Martignetti, et al. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook, I. D., F. Shanahan, and P. J. Farrell. 1994. Epstein-Barr virus SM protein. Virology 205:217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Court, D. L., J. A. Sawitzke, and L. C. Thomason. 2002. Genetic engineering using homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:361-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Court, D. L., S. Swaminathan, D. Yu, H. Wilson, T. Baker, M. Bubunenko, J. Sawitzke, and S. K. Sharan. 2003. Mini-lambda: a tractable system for chromosome and BAC engineering. Gene 315:63-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davison, A. J., and J. E. Scott. 1986. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J. Gen. Virol. 67:1759-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietz, P., B. G. Klupp, W. Fuchs, B. Kollner, E. Weiland, and T. C. Mettenleiter. 2000. Pseudorabies virus glycoprotein K requires the UL20 gene product for processing. J. Virol. 74:5083-5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn, W., C. Chou, H. Li, R. Hai, D. Patterson, V. Stolc, H. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellison, K. S., R. A. Maranchuk, K. L. Mottet, and J. R. Smiley. 2005. Control of VP16 translation by the herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP27. J. Virol. 79:4120-4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enquist, L. W., and J. P. Card. 2003. Recent advances in the use of neurotropic viruses for circuit analysis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13:603-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everett, R. D. 1986. The products of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) immediate early genes 1, 2, and 3 can activate HSV-1 gene expression in trans. J. Gen. Virol. 67:2507-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everett, R. D. 1984. Trans-activation of transcription by herpes virus products: requirement for two HSV-1 immediate-early polypeptides for maximum activity. EMBO J. 3:3135-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flamand, A., T. Bennardo, N. Babic, B. G. Klupp, and T. C. Mettenleiter. 2001. The absence of glycoprotein gL, but not gC or gK, severely impairs pseudorabies virus neuroinvasiveness. J. Virol. 75:11137-11145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontaine-Rodriguez, E. C., T. J. Taylor, M. Olesky, and D. M. Knipe. 2004. Proteomics of herpes simplex virus infected cell protein 27: association with translation initiation factors. Virology 330:487-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]