Abstract

The contribution of C/EBP proteins to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) lytic gene expression and replication in epithelial cells was examined. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines constitutively expressed C/EBPβ and had limited C/EBPα expression, while the AGS gastric cancer cell line expressed significant levels of both C/EBPα and C/EBPβ. Induction of the lytic cycle in EBV-positive AGS/BX1 cells with phorbol ester and sodium butyrate treatment led to a transient stimulation of C/EBPβ expression and a prolonged increase in C/EBPα expression. In AGS/BX1 cells, endogenous C/EBPα and C/EBPβ proteins were detected associated with the ZTA and oriLyt promoters but not the RTA promoter. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirmed binding of C/EBP proteins to multiple sites in the ZTA and oriLyt promoters. The response of these promoters in reporter assays to transfected C/EBPα and C/EBPβ proteins was consistent with the promoter binding assays and emphasized the relative importance of C/EBPs for activation of the ZTA promoter. Mutation of the oriLyt promoter proximal C/EBP site had little effect on ZTA activation of the promoter in a reporter assay. However, this mutation impaired oriLyt DNA replication, suggesting a separate replication-specific contribution for C/EBP proteins. Finally, the overall importance of C/EBP proteins for lytic gene expression was demonstrated using CHOP10 to antagonize C/EBP DNA binding activity. Introduction of CHOP10 significantly impaired induction of the ZTA, RTA, and BMRF1 proteins in chemically treated AGS/BX1 cells. Thus, C/EBPβ and C/EBPα expression are associated with lytic induction in AGS cells, and expression of C/EBP proteins in epithelial cells may contribute to the tendency of these cells to exhibit constitutive low-level ZTA promoter activity.

Induction of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) lytic cycle has been examined predominantly in B cells. A hierarchy of viral gene expression is recognized in which the lytic transactivator ZTA (also called ZEBRA, Z, BZLF1, and EB1) is the first viral protein expressed, followed by the transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulatory proteins RTA (R) and MTA (SM) and subsequently the complement of EBV early and late genes (2, 3, 20). The key role of ZTA in the lytic reactivation process has resulted in an extensive examination of the regulation of the promoter that drives the BZLF1 open reading frame encoding ZTA. Induction of the lytic cycle in Akata cells through cross-linking of the B-cell receptor has defined a pathway in which primary cell-mediated responses are followed by a ZTA-induced autoamplification of ZTA protein expression (5, 9, 56, 71) mediated through two ZTA binding sites in the BZLF1 promoter (Zp) (21, 38, 62). Induction of the Zp following B-cell-receptor coupled signaling is dependent on the activity of the receptor-associated Syk and Btk protein tyrosine kinases (36) and on activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway (30). Expression of ZTA is also induced by the cytokine transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (17, 18, 71), and three binding sites for SMAD proteins, the effectors of TGF-β signaling, have been identified in the Zp (37). Other EBV lytic cycle-inducing agents are phorbol esters, histone deacetylase inhibitors, and calcium ionophores. Phorbol ester treatment activates protein kinase C and the responsive cis-acting signals were mapped to the ZI and ZII (CRE/AP-1) Zp elements (7, 22). The CRE/AP-1 sites bind activating transcription factor 1 (ATF-1) and ATF-2 (41, 45, 68), and both ZTA and RTA induce ATF-2 phosphorylation and activation (1). The Zp response to calcium-dependent signaling also mapped to the ZI and ZII sites. The ZIA, ZIB, and ZID sites bind myocyte enhancer factor 2D (MEF-2D) (9, 43), which recruits histone deacetylases to repress the uninduced Zp (25). Calcium activation of MEF-2 response elements is mediated by two calcium calmodulin-dependent enzymes, the phosphatase calcineurin and the kinase type IV/Gr (6, 11). Other negative regulatory elements in the Zp are the promoter proximal ZV element, which binds the zinc-finger E-box binding factor ZEB (32, 33), and promoter distal elements that bind the transcription factor YY1 (49) and the E-box binding protein E2-2 (59).

The ZII and ZIIIB elements in the Zp have recently been shown to contain binding sites also for cellular CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα) (70). Cross-linking the B-cell receptor of Akata cells, a process that induces the EBV lytic cycle, also induces C/EBPα expression (70). In a series of reinforcing interactions, C/EBPα activates the Zp, ZTA interacts with C/EBPα and stabilizes the C/EBPα protein, and ZTA cooperates with C/EBPα in activation of the C/EBPα promoter (69). ZTA induces cell cycle arrest through mechanisms that include induction of p21 (10, 47, 51, 70), and C/EBPα is a key participant in p21 induction. ZTA-mediated cell cycle arrest does not occur in C/EBPα null cells (70).

C/EBPα is a member of a bZIP family of transcription factors that includes C/EBPβ, C/EBPγ, C/EBPδ, C/EBPɛ, and C/EBPζ (CHOP10/GADD153) (55). C/EBPs bind a consensus DNA sequence (A/G) TTGCG (C/T) AA (C/T) as homodimers or as heterodimers with other family members. CHOP10 lacks a functional DNA binding domain, and heterodimerization with other C/EBP proteins negatively regulates their DNA binding activity. Heterodimers can also form with c-Fos and CREB/ATF, and these heterodimers do not bind to consensus C/EBP sites. C/EBPα and C/EBPβ are expressed as multiple protein forms that result from translational initiation at internal AUG codons. C/EBPα has two major forms, p42 and p30. The N-terminally deleted p30 C/EBPα form does not function as a transcriptional activator and lacks antimitotic activity. C/EBPβ has four in-frame AUG codons and is translated as four isoforms of 38, 35, 21, and 14 kDa. The 21-kDa liver inhibitory protein (LIP) isoform is also generated by proteolytic cleavage of full-length C/EBPβ. C/EBP proteins also affect proliferative responses through protein-protein interactions. C/EBPα binds to and blocks the degradation of p21/WAF1/CIP1 (61), binds to the cell cycle regulatory kinases CDK2 and CDK4, inhibiting their activity (26, 65) and promoting their degradation (64), and binds to pRb to form C/EBPα-Rb-E2F4 complexes (29).

Induction of the EBV lytic cycle is linked to cellular differentiation. B-cell differentiation into plasma cells in vivo is associated with expression of BZLF1 transcripts, and induction of a Zp-reporter plasmid was also associated with interleukin-2- and interleukin-10-induced plasma cell differentiation in vitro (35). Treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)-KT cells with 5′-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine induced p53, p27 and p21 expression prior to induction of ZTA protein, and treatment of Rael cells with 5′ azacytidine resulted in a G1 cell cycle arrest that also preceded ZTA induction (52). Further, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical analyses of EBV-infected tongue has found replication of EBV DNA and expression of ZTA protein to be associated with the more differentiated layers of the tongue epithelium (27, 60, 63, 72). C/EBPα and C/EBPβ are involved in cell cycle regulation and cellular differentiation responses. For example, hormone treatment of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes activates expression of C/EBPβ, leading to several rounds of mitotic clonal expansion, which is a prerequisite for differentiation. C/EBPβ subsequently induces C/EBPα expression, which causes the cells to exit the cell cycle and differentiate (57, 58, 74). The contribution of C/EBPα to ZTA induction and function has been examined previously in B cells (69, 70). However, there are indications that aspects of the regulation of EBV gene expression may differ between B cells and epithelial cells (28, 31, 34, 73). The expression of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ in nasopharyngeal epithelial cell lines and the gastric carcinoma AGS cell line was therefore examined, and the contribution of these C/EBP proteins to lytic EBV gene expression and replication was evaluated in EBV-converted AGS/BX1 carcinoma cells (8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and lytic induction.

EBV-negative HK1, NP69, CNE1, CNE2, and HONE1 cells and EBV-positive c666-1 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. EBV-negative HeLa and EBV-positive D98/HR-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. EBV-negative AGS cells and EBV-positive AGS/BX1 cells (8) were grown in Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. For EBV lytic cycle induction, AGS/BX1 cells were treated for 24 h with 20 ng/ml 12-o-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and 2.5 mM sodium butyrate (BA) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.).

Plasmids.

pRTS21 is an pSG5 (Stratagene)-based mammalian expression vector carrying the genomic version of the EBV ZTA gene. Wild-type C/EBPα (pHC125B), C/EBPβ (pHC108B), and CHOP10 (pHC121A) were PCR amplified from HeLa cDNA and cloned into a pSG5 vector modified with a Flag epitope (pJH253). Zp-Luc (pHC133) is a luciferase reporter containing an insertion of a 260-bp HindIII/XbaI fragment from position −221 to +39 of the EBV ZTA promoter. pBBV-α and pBBV-β are in vitro transcription-translation vectors encoding full-length C/EBPα and C/EBPβ, respectively. pYNC100A is a black beetle virus (BBV) vector carrying a cDNA for wild-type ZTA. The Rp-driven luciferase (Rp-Luc; pGL264) reporter was generated by PCR amplification using the EBV BamHI R fragment as a template and the pGL2Luc vector (Promega). A wild-type oriLyt fragment was amplified by PCR with pDH124 as the template and the primers 5′-GACTGGATCCGGCTCGCCTTCTTTTATCCTC and 5′-AGTCACGCGTGGGTTAGTGATGAAACAGGC and ligated into the BglII and MluI sites of pGL2 (CloneTech) to form pGL108. The C/EBP site in the oriLyt fragment was mutated to form pGL226. pBluescript-orilyt (pGL208) was generated by cloning the oriLyt BamHI/PstI fragment derived from B95-8 BamHI-H into the pBluescript II SK(+) vector (Stratagene).

DNA transfection and luciferase assays.

Transfection of HeLa cells was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates 1 day prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with a total of 1 μg of DNA and harvested at 48 h posttransfection. Luciferase activity was measured for 10 s with a Lumat LB9501 luminometer (Berthold Systems, Inc.) using a commercial assay system and Renilla luciferase activity as an internal control (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

Preparation of cell extracts and Western blotting.

Approximately 2 × 106 cells were pelleted by centrifugation and solubilized in 500 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 5 μg/ml of aprotinin, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate. The cell lysate was sonicated for 30 s and boiled for 5 min. Lysate (15 μl) was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by analysis by Western blotting with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) as the secondary antibody and by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Bands were visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

EMSA.

Proteins used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were in vitro translated by using a TNT quick-coupled transcription-translation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's procedures. Mixtures containing 2 μg of plasmid DNA, 1 μl of RNase inhibitor, 2 μl of 1 mM methionine, and 40 μl of TNT Quick Master Mix were incubated at 30°C for 90 min and stored at −80°C. For the EMSA, 2 to 4 μl of in vitro-translated proteins was used for each reaction in a binding solution containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM PMSF, 1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, and 2 μg of poly(dI · dC). After the annealing step, double-stranded oligonucleotides were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP by incubation with Klenow DNA polymerase in the presence of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (without dCTP). Approximately 50,000 cpm of the 32P-labeled probe was added to each sample and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For supershift experiments, 1 μl of C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, or ZTA antibody was added to the mixture after 30 min and incubated for 30 min before gel loading. Samples were separated on a 4.5% polyacrylamide gel in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM EGTA at 150 V and 4°C as described previously (12). The gel was subsequently dried and subjected to autoradiography with Kodak film. The following oligonucleotide pairs were purchased from Invitrogen and annealed to form the respective probes: LGH4248 (5′-GATCAGCCACAGGCATTGCTAATGTACCTCATAGACA-3′) and LGH4249 (5′-GATCTGTCTATGAGGTACATTAGCAATGCCTGTGGCT-3′ for the Z2 probe; LGH4309 (5′-GATCACGTCCCAAACCATGACATCACAGAGGAGGCTG-3′) and LGH4310 (5′-GATCCAGCCTCCTCTGTGATGTCATGGTTTGGGACGT-3′) for the Z3 probe; LGH4252 (5′-GATCGAGGCTGGTGCCTTGGCTTTAAAGGGGAGATGT-3′) and LGH4253 (5′-GATCACATCTCCCCTTTAAAGCCAAGGCACCAGCCTC-3′) for the Z4 probe; LGH6900 (5′-GATCTCAGCATCGCTTAAGTATGAGTGGGCAGCA-3′) and LGH6901 (5′-GATCTGCTGCCCACTCATACTTAAGCGATGCTGA-3′) for the R1 probe; LGH6389 (5′-GATCCCTGACCATCACATGGGGCATTAGGCGACT-3′) and LGH6390 (5′-GATCAGTCGCCTAATGCCCCATGTGATGGTCAGG) for the R2 probe; LGH6387 (5′-GATCGGGACAATCGCAATATAAAACCCTGACCAT-3′) and LGH6388 (5′-GATCATGGTCAGGGTTTTATATTGCGATTGTCCC-3′) for the R3 probe; LGH6385 (5′-GATCCTTTTATGAGCCATTGGCATGGGCGGGACA-3′) and LGH6386 (5′-GATCTGTCCCGCCCATGCCAATGGCTCATAAAAG) for the R4 probe; LGH6383 (5′-GATCAAGGCCGGCTGACATGGATTACTGGTCTTT-3′) and LGH6384 (5′-GATCAAAGACCAGTAATCCATGTCAGCCGGCCTT-3′) for the R5 probe; LGH5107 (5′-CATGGGCTTCTTATTGGTTAATTCAGGTGT-3′) and LGH5108 (5′-CATGACACCTGAATTAACCAATAAGAAGCC-3′) for the O1 probe; LGH5153 (5′-CATGGAGGTTATTCTATTGGGATAACGAGA-3′) and LGH5154 (5′-CATGTCTCGTTATCCCAATAGAATAACCTC-3′) for the O2 probe; LGH5169 (5′-CATGTGGGGGTGGAAATATGAGCAAGAATA-3′) and LGH5170 (5′-CATGTATTCTTGCTCATATTTCCACCCCCA-3′) for the O3 probe; LGH5109 (5′-CATGTCCGTTTTAATGGTAGAATAACCTAT-3′) and LGH5110 (5′-CATGATAGGTTATTCTACCATTAAAACGGA-3′) for the O4 probe; LGH5155 (5′-CATGAGGAGGGGGAGGATTGGGCTCCGCCC-3′) and LGH5156 (5′-CATGGGGCGGAGCCCAATCCTCCCCCTCCT-3′) for the O5 probe; LGH5167 (5′-CATGTGCCTTGTCCCGTGGACAATGTCCCT-3′) and LGH5168 (5′-CATGAGGGACATTGTCCACGGGACAAGGCA-3′) for the O6 probe.

ChIP assay.

AGS/BX1 cells were treated with TPA and BA for 24 h, and 107 cells were harvested for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Proteins were cross-linked to DNA by adding formaldehyde directly to the culture medium to a final concentration of 1% and incubating for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml, and 1 μg of pepstatin A/ml), resuspended in 200 μl of SDS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors, and incubated for 10 min on ice. DNA was sheared by sonicating samples on ice, and samples were centrifuged to collect the supernatants. The supernatants were then diluted in 1,800 μl of ChIP dilution buffer before 80 μl of salmon sperm DNA-protein A agarose slurry was added, followed by agitation for 30 min at 4°C. After the agarose beads were spun down, precleared samples were aliquoted; antibodies against ZTA (Argene), C/EBPα, or C/EBPβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added to each aliquot of 500 μl, and samples were rotated for 2 h at 4°C. A total of 60 μl of salmon sperm DNA-protein A agarose slurry was then added to each sample, and samples were rotated for another hour at 4°C. The beads were subsequently washed in low-salt immune complex wash buffer, high-salt immune complex wash buffer, and LiCl immune complex wash buffer and then washed twice in Tris-EDTA buffer. After the washing steps, 250 μl of freshly prepared elution buffer (1% SDS-0.1 M NaHCO3) was added to the beads, and samples were vortexed and incubated for 15 min at 20°C with rotation. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation, and the elution was repeated with another 250 μl of elution buffer. Then 20 μl of 5 M NaCl was added to each sample, and samples were incubated at 65°C for 12 h before proteinase K treatment, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. DNA pellets were resolved in 20 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer, and 2 μl was used as the template for PCR. For detection of the immunoprecipitated EBV ZTA promoter region, two primers, LGH3207 (5′-CATTCTAGACTTCAGCAAAGATAGCAAAGG-3′) and LGH3208 (5′-CGCAAGCTTGATGAATGTCTGCTGCATGC-3′), specific for a 220-bp Zp fragment, were used for PCR amplification. For detection of the EBV RTA promoter region, primers LGH6902 (5′-GACTAGATCTAAAAAGGCCGGCTGACATG-3′) and LGH6903 (5′-GACTACGCGTACACCCAGACATAAGTTGTG-3′), specific for a 421-bp region of Rp, were used for PCR amplification. EBV oriLyt primers LGH5036 (5′-CAGGTGTGTCATTTTAGCCC-3′) and LGH5040 (5′-TCCTGGTTCAACCCTATGGAG-3′), specific for a 185-bp region in the oriLyt enhancer, were used for PCR amplification. The PCR products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel and detected by ethidium bromide staining.

Immunofluorescence assay.

D98/HR-1 cells were seeded at 8 × 104 cells per well in two-well slide chambers. Cells were transfected with 3 μg of DNA by the calcium phosphate procedure. After transfection, cells were incubated in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum for 16 h at 35°C in 3% CO2, followed by a medium change and a further 24 h of incubation. Cells were washed in PBS, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized for 20 min on ice in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibody for 60 min at 37°C and with secondary antibody at 37°C for 30 min. Between each staining step, the cells were washed in PBS three times for 5 min. The antibodies used were anti-BMRF1 (EA-D) monoclonal antibody (1:200; ABI Advanced Biotechnologies, Inc., Columbia, Md.), rabbit anti-Flag antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1:200), and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.).

Replication assay.

Two micrograms of oriLyt plasmid DNA (pGL216) or O1 mutant oriLyt (pGL226) was electroporated into D98/HR-1 cells with or without 5 μg of ZTA and 5 μg of RTA plasmid DNA in 0.5 ml of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II with a 0.4-cm cuvette and set at capacitance 950 μF and 180 V. Two days after electroporation, the DNA was prepared with the Wizard SV genomic DNA purification system (Promega). The DNA was cleaved with EcoRI and DpnI or EcoRI and MboI to distinguish between replicated plasmid DNA and input DNA that had not replicated in eukaryotic cells. After the digestion had gone to completion, the DNA was purified and concentrated by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). A 1-kb ApaLI fragment from the oriLyt plasmid vector (pBluescript II SK[+]) was used as the probe for Southern blot hybridization.

Flow cytometry sorting.

A CHOP10 expression vector, or SG5 vector, was cotransfected with a red color expression vector DsRed into AGS/BX1 cells. After 24 h, cells were treated with TPA and BA for another 24 h. Then cells were collected in PBS and subjected to flow cytometry sorting for DsRed in the Core Facility of the Johns Hopkins Oncology Center.

Quantitative PCR.

AGS/BX1 cells were transfected with DsRed plus either SG5 vector or a CHOP10-expressing vector and treated with TPA and BA 24 h after transfection. Cells were subjected to flow cytometry sorting for DsRed expression. mRNA was extracted 24 h after treatment by using a GenElute Direct mRNA Miniprep kit (Sigma). Cells were harvested and resuspended by vortexing in 0.5 ml of lysis solution containing proteinase K (0.2 mg/ml), followed by incubation at 65°C for 10 min. Next, 32 μl of 5 M NaCl and 25 μl of oligo(dT) beads were added to the solution, which was allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min. The oligo(dT)-mRNA complex was pelleted by microcentrifugation for 5 min at maximum speed, washed once with 350 μl of wash solution, and washed twice with 350 μl of low-salt wash solution. The poly(A) mRNA was eluted at 65°C in 100 μl of elution solution. For reverse transcription (RT), the following Promega reagents were used: 20 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, 10 μl of avian myeloblastosis virus 5× RT buffer, 1 μl of RNasin RNA inhibitor, 4 μl of 5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 0.5 μg of random primers. These reagents were mixed and incubated at 42°C for 1 h with 30 μl of mRNA and H2O to a final volume of 50 μl. The synthesized cDNAs were used as templates for ZTA PCR. PCRs were set up in a volume of 50 μl using a SyberGreen PCR Master Mix Kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). DNA amplifications were carried out in a 96-well reaction plate in a Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems 7700 Sequence Detector. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, and multiple negative water blanks were included in each analysis. Primers LGH2617 (5′-ACATCTGCTTCAACAGGAGG-3′) and LGH2618 (5′-AGCAGACATTGGTGTTCCAC-3′) were used to amplify ZTA transcripts. Primers LGH4859 (5′-ATTCAACGGCACAGTCAAGG-3′) and LGH4860 (5′-TGGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′) were used to amplify GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) transcripts for normalization. Quantitation of EBV genome copy number used TATA-binding protein as an internal control (5′-CACGAACCACGGCACTGATT and 5′-TTTTCTTGCTGCCAGTCTGGAC) and primers for RTA (5′-CCAAGAGAGCGATGAGAGACCCATATTCC and 5′-GCTATCCCTGAGGCCCTTCTTCCTTTTAAC). Cycle conditions were 2 min at 50°C, 95°C for 10 min, and then 40 to 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C.

RESULTS

Expression of C/EBP proteins in epithelial cell lines.

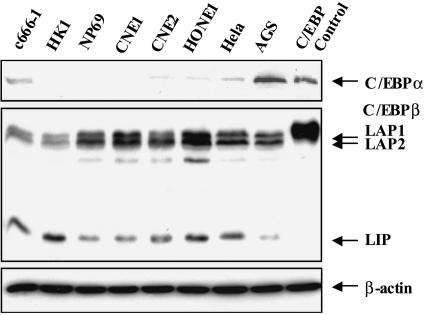

A Western blot analysis of endogenous C/EBP protein expression in six different NPC cell lines found C/EBPα expression in c666-1, CNE2 and HONE1 that was similar to the low expression seen in HeLa cells while expression in HK1, NP69 and CNE1 was below detectable levels (Fig. 1). In contrast, there was strong expression of the C/EBPβ isoforms LAP1, LAP2, and LIP in all the NPC cell lines tested. The gastric carcinoma AGS cell line was found to express significant levels of both C/EBPα and C/EBPβ (Fig. 1). Flag-C/EBPα- or Flag-C/EBPβ-transfected HeLa cell extracts were used as a positive control in the Western blots.

FIG. 1.

Endogenous C/EBPα and C/EBPβ expression in epithelial cell lines. A Western blot probed with C/EBPα polyclonal antibody (upper), C/EBPβ monoclonal antibody (middle), and control β-actin monoclonal antibody (lower) shows the levels of endogenous C/EBPα and C/EBPβ in the EBV-positive NPC epithelial cell line c666-1; the EBV-negative NPC cell lines HK1, NP69, CNE1, CNE2, and HONE1; the EBV-negative cervical cancer cell line HeLa; and the EBV-negative gastric carcinoma cell line AGS. HeLa cells transfected with Flag-C/EBPα- and Flag-C/EBPβ-expressing vectors were used as a positive control (C/EBP control).

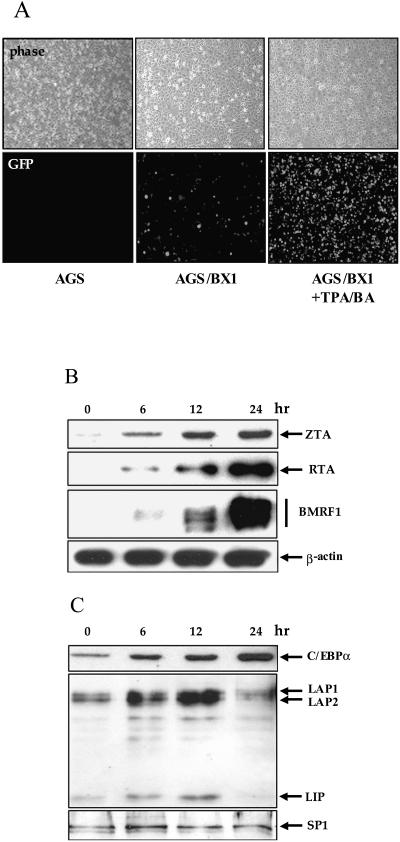

The EBV lytic cycle can be activated by treatment of infected cells with a combination of phorbol esters and sodium butyrate. The effect of this treatment on C/EBP protein expression was examined in AGS/BX1 cells which were generated by infection of AGS cells with recombinant BX1 virus carrying an introduced green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (8, 48). Treatment of AGS/BX1 with TPA and BA effectively induces the viral lytic cycle. There was an increase in GFP fluorescence (Fig. 2A) that reflected an eightfold increase in EBV DNA copy number at the 24-h time point as measured by quantitative PCR (data not shown). Induction of expression of the lytic ZTA, RTA, and BMRF1 proteins also was detected (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis revealed that the expression of endogenous C/EBPβ proteins that was induced early after treatment was maximal at 12 h posttreatment and had declined to basal levels by 24 h (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, C/EBPα expression increased throughout the 24-h induction period (Fig. 2C), and the steady increase in expression from 6 h to 24 h posttreatment was mirrored by the increase seen for the ZTA protein (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

TPA and BA treatment of AGS/BX1 cells induces C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, and the EBV lytic cycle. (A) EBV-BX1-infected AGS cells (AGS/BX1) and the parental AGS cells were treated with TPA and BA for 24 h. GFP expression (lower panel) and phase (upper panel) were examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope. (B and C) Western blots of extracts of TPA- and BA-treated AGS/BX1 cells harvested at different time points showing induction of EBV lytic proteins (B) and induction of C/EBPβ and C/EBPα expression followed by a decline in C/EBPβ expression at 24 h (C). The transcription factor SP1 was used as a marker for equal protein loading.

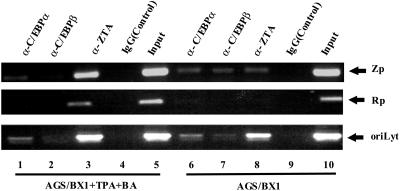

Association of C/EBP proteins with the EBV ZTA and RTA promoters and oriLyt.

ChIP assays were performed on treated and untreated AGS/BX1 cells to examine the association of endogenous C/EBP proteins with the ZTA and RTA promoters and oriLyt. Prior to induction, both C/EBPα and C/EBPβ were associated with the ZTA promoter and oriLyt, and there was minimal association with the RTA promoter (Fig. 3, lanes 6 and 7). ZTA was also readily detected with the ZTA promoter and oriLyt probes prior to induction (Fig. 3, lane 8). The presence of ZTA is consistent with the detection of low levels of ZTA protein in untreated AGS/BX1 cells (Fig. 2B), and the more intense signal obtained with the oriLyt probe is likely to reflect the presence of the higher number of ZTA binding sites in oriLyt. After chemical induction for 24 h, increased association of ZTA with the ZTA and RTA promoters and oriLyt was detected (Fig. 3, lane 3). C/EBPα remained associated with the ZTA promoter and oriLyt and was not detected on the RTA promoter (Fig. 3, lane 1). C/EBPβ was no longer detected associated with the ZTA promoter and was only weakly associated with oriLyt. This is consistent with the downregulation of C/EBPβ seen at 24 h postinduction (Fig. 3, lane 2). No Zp, Rp, or oriLyt PCR products were detected in control precipitations using IgG (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 9).

FIG. 3.

Endogenous C/EBP proteins are associated with the ZTA promoter and oriLyt. ChIP assays performed on untreated and TPA- and BA-treated AGS/BX1 cells, showing that Zp DNA (upper panel) and oriLyt DNA (lower panel) are more strongly associated with C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and ZTA than Rp DNA (middle panel) in untreated cells (lanes 6, 7, and 8). After lytic induction, ZTA expression and binding were amplified (lane 3), and C/EBPβ binding was diminished (lane 2). IgG (Control), nonspecific IgG; Input, PCR performed on total cell extract.

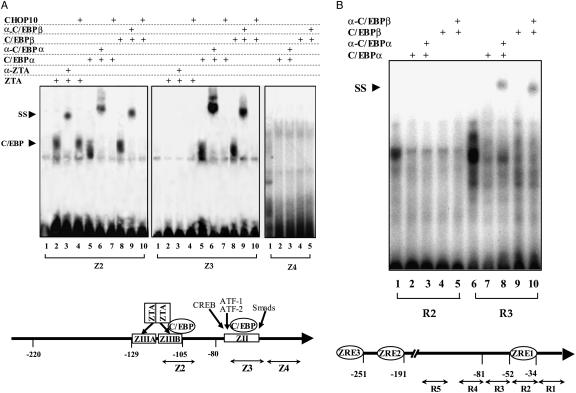

C/EBP binding sites in the ZTA and RTA promoters and oriLyt were examined using EMSAs and in vitro translated C/EBP proteins (Fig. 4). Two binding sites for C/EBPα have previously been mapped in the ZTA promoter (70). These sites, present in the Z2 and Z3 oligonucleotide probes, also bound C/EBPβ (Fig. 4A). A control ZTA promoter sequence (Ζ4) bound neither C/EBP protein. Binding of the C/EBP proteins to the Z2 and Z3 oligonucleotides was abolished by addition of in vitro translated CHOP10 (Fig. 4A, lanes 7 and 10). The Z2 oligonucleotide contains overlapping ZTA and C/EBP binding sites (70). Binding of ZTA to Z2 was not affected by CHOP10 (Fig. 4A, lane 4).

FIG. 4.

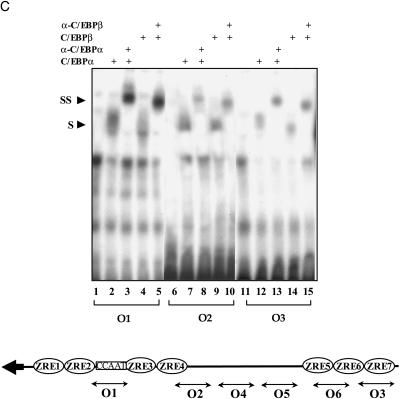

C/EBPα and C/EBPβ proteins bind to lytic promoters in vitro. (A) Binding to the ZTA promoter. (Top) EMSA with probe Z2 (left column) showing that in vitro translated ZTA, C/EBPα, and C/EBPβ all bind to the ZTA (−117 to −109) promoter region. EMSA with probe Z3 (middle column) shows that in vitro translated C/EBPα and C/EBPβ both bind to the ZTA (−69 to −61) promoter region. Z4 (−42 to −36) was used as a negative control. Binding of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ, but not binding of ZTA, to the ZTA promoter can be blocked by in vitro translated CHOP10. (Bottom) Schematic illustration of the location of ZTA and C/EBP binding sites within the ZTA promoter. (B) Limited C/EBP binding to the RTA promoter. (Top) EMSA with probes R2 and R3. Only supershifted bands with C/EBPα polyclonal or C/EBPβ monoclonal antibodies can be seen and only with the R3 probe. (Bottom) Schematic illustration of the location of ZTA binding sites and the tested C/EBP binding sites within the RTA promoter. (C) C/EBP binding to oriLyt. (Top) EMSA with O1, O2, and O3 probes showing that in vitro translated C/EBPα and C/EBPβ bind to oriLyt. (Bottom) Schematic illustration of the location of ZTA binding sites and the tested C/EBP binding sites within oriLyt.

Binding of C/EBP proteins to the RTA promoter was minimal in the ChIP assays. However, five potential C/EBP sites in the RTA promoter were synthesized as oligonucleotides and tested for C/EBP binding. Only the R3 oligonucleotide (−42 to −71 in the RTA promoter) bound C/EBPs in the in vitro assay. Binding of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ to the R3 site was only detected as a supershifted species in the presence of anti-C/EBP antibody (Fig. 4B, lanes 8 and 10), suggesting that the R3 site had a low affinity for the C/EBP proteins relative to the ZTA promoter binding sites. The negative results obtained with the R2 probe (Fig. 4B) are representative of the data for the four nonbinding RTA promoter probes tested (data not shown).

Six potential C/EBP binding sites in oriLyt were tested for C/EBP binding by EMSA. Binding of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ was observed with the two oriLyt promoter probes O1 and O2 and the oriLyt enhancer probe O3 (Fig. 4C). The bound proteins produced supershifted complexes in the presence of anti-C/EBP antibodies. Three other sequences (O4, O5, and O6; see Materials and Methods) located between the oriLyt promoter and enhancer regions (53246 and 53049 on the EBV B95-8 genome) and in the oriLyt enhancer at 53528 were also tested and did not bind C/EBP proteins (data not shown).

Response of the ZTA and RTA promoters to exogenous C/EBPs.

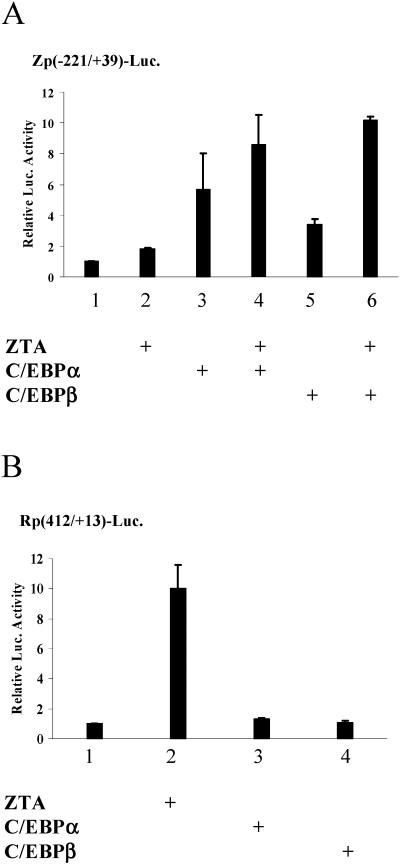

In reporter assays, the ZTA promoter is activated by transfected C/EBPα, and cooperative activation is seen with the combination of ZTA and C/EBPα (70). Constitutive C/EBPβ expression was more prevalent than C/EBPα expression in the NPC cell lines that we examined. The effect of transfection of C/EBPβ on a ZTA promoter-reporter was compared with that observed for C/EBPα (Fig. 5A). In transfected HeLa cells, C/EBPβ activated the reporter approximately 60% as effectively as C/EBPα (Fig. 5A, lane 5 versus lane 3) and more effectively than ZTA (Fig. 5A, lane 2). In the presence of cotransfected ZTA, C/EBPβ produced a similar activation to that seen with ZTA plus C/EBPα (Fig. 5A, lane 6 versus lane 4).

FIG. 5.

Effect of exogenous C/EBPs on the Zp and Rp promoters in reporter assays. (A) Activation of a Zp-Luc reporter. HeLa cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of plasmid DNA encoding Zp (−221 to +39)-Luc and 0.05 μg of effector plasmid DNA expressing ZTA, C/EBPα, or C/EBPβ alone or in the indicated combinations. (B) The Rp-Luc reporter is nonresponsive to C/EBPs. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding Rp (−412 to +13)-Luc and effector plasmid DNAs expressing ZTA, C/EBPα, or C/EBPβ. The total amount of effector plasmid DNA used in each transfection was normalized to 1 μg by adding vector DNA. The assays were repeated three times. Error bars indicate the standard deviation.

An RTA promoter-reporter was activated by ZTA but did not show any response to cotransfected C/EBPα or C/EBPβ (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4). This result is consistent with the EMSA and ChIP analyses. Note that ZTA binds to and preferentially activates an Rp that contains a CpG methylated ZTA binding site (4), and so the ZTA response seen in this assay would be expected to be suboptimal. The reporter assays suggest that C/EBPα and C/EBPβ play a more important role in activation of the ZTA promoter than in RTA promoter responses.

C/EBP proteins and oriLyt promoter and replication responses.

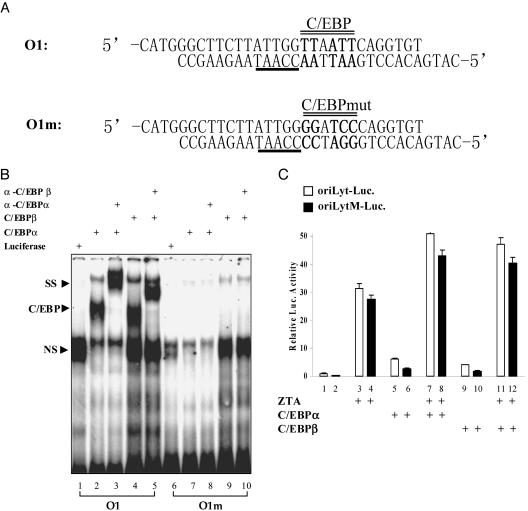

The ChIP and EMSA assays indicated that C/EBPs bound oriLyt. A previous analysis of oriLyt cis-acting sequences had found that a deletion that encompassed the O1 C/EBP site abolished oriLyt promoter activity and oriLyt replication (54). This deletion removed both the promoter CCAAT box and the overlapping O1 C/EBP site at 52875 on the EBV B95-8 genome. To further address the contribution of this oriLyt C/EBP site, we sought to introduce a mutation that would more specifically impact on C/EBP binding while sparing the CCAAT sequence. The wild-type and mutated O1 sequences shown in Fig. 6A were synthesized as oligonucleotides and tested for C/EBP binding. An EMSA performed with in vitro translated proteins showed binding of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ to the wild-type O1 probe and the generation of supershifted complexes in the presence of anti-C/EBP antibodies (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 to 5). No binding of C/EBPα or C/EBPβ was observed with the mutated O1m probe (Fig. 6B, lanes 7 to 10), and no specific complexes were detected with a control in vitro translated luciferase protein (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 and 6).

FIG. 6.

Effect of the O1 C/EBP site on oriLyt promoter activation. (A) Mutation of the O1 C/EBP site. Mutated bases are shown in bold. The CCAAT box is underlined, and the C/EBP site is indicated with a double line. (B) EMSA assay comparing binding of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ to a wild-type O1 probe (lanes 1 to 5) and a probe carrying a mutation in the O1 site (O1m) (lanes 6 to 10). (C) Minimal impact of the O1m mutation on oriLyt promoter activity. Reporter assays in which HeLa cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of wild-type oriLyt-Luc (oriLyt-Luc)reporter or the O1 mutant oriLyt-Luc (oriLyt M-Luc) reporter in the presence of 0.2 μg of cotransfected C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, or ZTA as indicated. The assay was repeated two times, and the deviation from the average is shown.

The O1m mutation was introduced into an oriLyt promoter-reporter, and the activities of the O1m mutant reporter and the wild-type oriLyt promoter reporter were compared in transfected HeLa cells. The wild-type promoter was activated sixfold by C/EBPα and fourfold by C/EBPβ (Fig. 6C, lanes 5 and 9 versus lane 1). The O1m oriLyt promoter retained 50% of the response to C/EBPα and C/EBPβ despite the absence of any cis-acting C/EBP sites in the promoter (Fig. 6C, lanes 5 versus 6 and 9 versus 10), indicating that some of the C/EBP responsiveness of the promoter was mediated indirectly. ZTA activated the wild-type oriLyt promoter 32-fold and the O1m promoter 84-fold (Fig. 6C, lanes 3 and 4). The relative activation of the O1m promoter was higher than that for the wild-type promoter because of the threefold drop in basal activity of the O1m promoter. The responsiveness of the O1m promoter to transfection with ZTA plus C/EBPα or C/EBPβ followed the same pattern in which the induced luciferase activity was similar to that of the wild-type promoter but the relative increase in activation was greater (129-fold versus 51-fold for C/EBPα plus ZTA [Fig. 6C, lane 8 versus lane 7] and 120-fold versus 47-fold for C/EBPβ plus ZTA [Fig. 6C, lane 12 versus lane 11]). The reporter assays indicated that C/EBPα and C/EBPβ activate the oriLyt promoter, although less effectively than ZTA. The O1 C/EBP site appeared to be nonessential for a robust ZTA-mediated oriLyt promoter response.

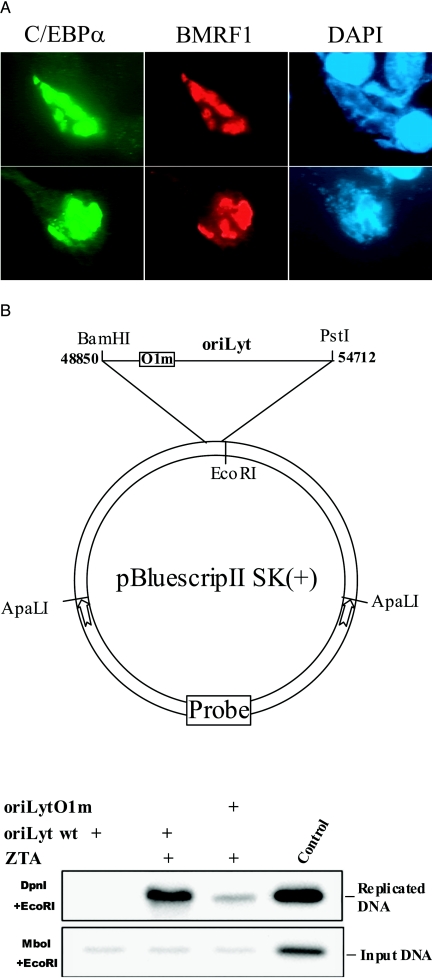

An immunofluorescence assay performed on D98/HR-1 cells induced to undergo lytic replication by transfection of ZTA showed Flag-C/EBPα accumulation in BMRF1-positive replication compartments (Fig. 7A), raising the possibility that the O1 oriLyt promoter C/EBP site might be relevant in the context of oriLyt replication. The O1m mutation was therefore introduced into a 5,868-bp BamHI-PstI oriLyt sequence, and a replication assay was performed. D98/HR-1 cells were transfected with the wild-type and O1m oriLyt plasmids plus ZTA and RTA to induce the endogenous lytic replication proteins. Forty-eight hours after transfection, DNA was extracted and digested with either MboI plus EcoRI or DpnI plus EcoRI. MboI recognizes the sequence GATC and cleaves unmethylated replicated DNA, while DpnI cuts the same sequence when it carries the bacterially imposed methylation pattern. The replicated EcoR1-cleaved oriLyt plasmid will therefore remain intact after EcoRI/DpnI cleavage, while the EcoRI-cleaved input DNA will remain intact after EcoRI-MboI cleavage. A Southern blot of the digested DNA samples was probed with a 32P-labeled vector DNA fragment so that only the transfected oriLyt DNA sequences would be detected. Replication of the oriLyt plasmid containing the mutated O1 C/EBP site was significantly impaired compared to the replication seen with the wild-type parental plasmid (Fig. 7B). Thus, the O1 C/EBP site is important for efficient oriLyt DNA replication.

FIG. 7.

The O1 C/EBP site preferentially affects oriLyt replication. (A) C/EBPα localizes into viral replication compartments. Immunofluorescence assays performed on D98/HR-1 cells transfected with ZTA to induce the EBV lytic cycle plus FLAG-tagged C/EBPα. Cells were stained for BMRF1 as a marker for viral replication compartments with anti-BMRF1 antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody. FLAG-tagged C/EBPα was detected with anti-Flag antibody, and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody and nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole). (B) Mutation of the promoter proximal C/EBP site impairs oriLyt replication. A wild-type oriLyt plasmid (oriLyt wt) or an oriLyt carrying a mutation in the O1 C/EBP site (oriLyt O1m) was transfected into D98/HR-1 cells together with ZTA and RTA for induction of lytic replication. After 48 h, genomic DNA was extracted, digested with DpnI and ECoRI to detect replicated DNA or with MboI and ECoRI to detect input DNA and then subjected to electrophoresis. A 1-kb ApaLI fragment from the oriLyt plasmid vector [pBluescript II SK(+)] was used as the probe for Southern blot hybridization.

C/EBP activity is necessary for effective induction of ZTA, RTA, and BMRF1 protein expression in AGS/BX1 cells.

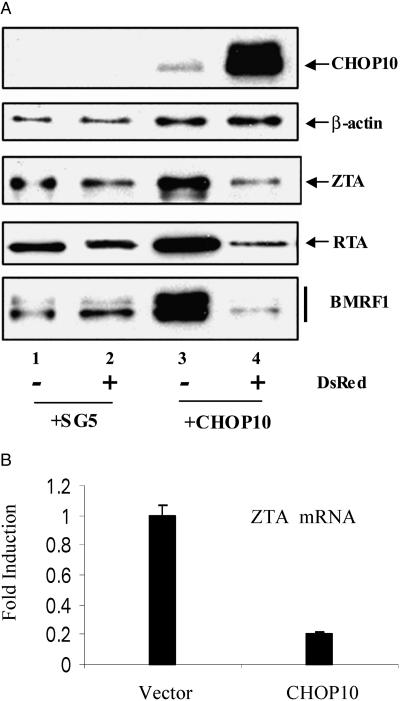

The contribution of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ to activation of lytic protein expression from the EBV genome was examined in AGS/BX1 cells that were transfected with a CHOP10 expression vector prior to lytic induction. CHOP10 is a C/EBP family member that heterodimerizes with C/EBPα and C/EBPβ to negatively regulate their DNA binding ability. AGS/BX1 cells were transfected with CHOP10 plus a DsRed expression plasmid or with empty vector plus DsRed. After 24 h the cells were treated with TPA and BA for 24 h to induce the EBV lytic cycle. The cells were then subjected to flow cytometry sorting for DsRed expression. Protein extracts from the DsRed-positive (transfected) and DsRed-negative (untransfected) cells were analyzed by Western blotting for CHOP10, ZTA, RTA, and BMRF1 protein expression (Fig. 8A). Cellular β-actin served as a control for equal protein loading. In AGS/BX1 cells cotransfected with empty vector and DsRed prior to induction, there was no detectable expression of CHOP10 and no difference in the expression of ZTA, RTA, or BMRF1 between the DsRed-positive and DsRed-negative populations (Fig. 8A, lane 1 versus lane 2). Examination of the cell population transfected with CHOP10 and DsRed showed that the DsRed sorting greatly enriched for transfected cells as CHOP10 expression was detected at high levels in the DsRed-positive population and was present only at a very low level in the DsRed-negative population (Fig. 8A, lanes 3 and 4). CHOP10 expression led to an approximately fivefold reduction in ZTA induction, an eightfold reduction in RTA induction, and a 20-fold reduction in induction of BMRF1. RNA was also prepared from the CHOP10-transfected DsRed-positive and vector-transfected DsRed-positive cell populations, and quantitative RT-PCR was performed to determine ZTA transcript levels. CHOP10 expression resulted in a fivefold reduction in ZTA transcript levels in this experiment (Fig. 8B). As summarized in Fig. 9, we interpret these data to indicate that CHOP10 interference with C/EBPα and C/EBPβ DNA binding leads to a reduction in ZTA transcription and consequently in ZTA protein expression. The loss of ZTA is then reflected in a diminished induction of RTA protein expression, and the combined impact on ZTA and RTA protein levels and loss of C/EBP transcriptional activity ablates induction of BMRF1.

FIG. 8.

Loss of C/EBP activity impairs EBV lytic protein induction. A CHOP10 expression vector and a red expression vector, DsRed, or vector DNA plus DsRed were cotransfected into AGS/BX1 cells. After 24 h, cells were treated with TPA and BA for another 24 h to induce the lytic cycle. Cells were then collected and subjected to flow cytometry sorting based on DsRed expression. (A) Western blot showing that CHOP10-transfected DsRed-positive cells have decreased levels of EBV lytic protein expression (lanes 3 and 4). DsRed expression in vector-cotransfected cells does not affect EBV lytic protein induction (lanes 1 and 2). (B) CHOP10 reduces endogenous ZTA mRNA levels. Results of real-time RT-PCR analyses show that CHOP10-transfected DsRed positive cells have decreased ZTA mRNA expression compared to vector-transfected DsRed positive cells.

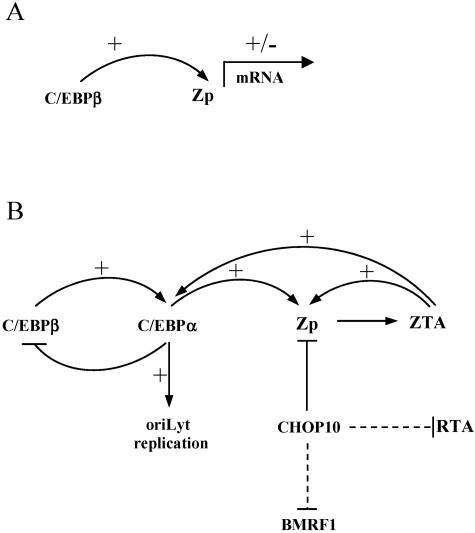

FIG. 9.

Summary of C/EBP activity in epithelial cells. (A) Constitutive expression of C/EBPβ allows low-level ZTA mRNA expression. (B) Stimuli such as phorbol esters and BA lead to a cycle of C/EBPβ upregulation, C/EBPα upregulation, and Zp activation, which result in a reinforcing loop of ZTA autoactivation and C/EBPα upregulation and stabilization. C/EBPα is also required for efficient oriLyt replication. Exogenous CHOP10 directly inhibits Zp activity. Down-regulation of RTA and BMRF1 is primarily an indirect consequence (dashed line) of reduced ZTA (and RTA) expression.

DISCUSSION

The majority of B-cell lines do not constitutively express C/EBPα and express either no constitutive C/EBPβ or only the negative 21-kDa LIP C/EBPβ isoform. C/EBPα is induced in Akata cells by cross-linking of the B-cell receptor, and induction of ZTA protein expression follows the same kinetics as induction of C/EBPα expression (69). Examination of NPC and gastric carcinoma epithelial cell lines revealed abundant constitutive C/EBPβ expression and limited C/EBPα expression, with the notable exception of the AGS gastric carcinoma cell line. Interestingly, EBV-converted AGS/BX1 cells also exhibit a low level of constitutive ZTA protein expression (Fig. 2). Transcripts for ZTA have been detected in NPC tissues (14, 40, 46) and in some EBV-positive gastric carcinomas (44, 67). In our ChIP analyses of AGS/BX1 cells, C/EBPβ was associated with the Zp prior to treatment of the cells with phorbol ester and BA, and in vitro C/EBPβ bound to the same sites in the Zp as C/EBPα. C/EBPβ was also able to activate the Zp in reporter assays. We suggest that expression of C/EBPβ in epithelial cells allows ZTA transcription at levels that may account for detection of BZLF1 transcripts by sensitive RT-PCR techniques. While C/EBPβ may poise the Zp to be more responsive to lytic induction stimuli, C/EBPβ is not capable of inducing ZTA protein expression to the stage where the ZTA autostimulation of the promoter occurs and maximal ZTA protein levels are expressed. Expression of c-Myc has been found to interfere with ZTA transactivation function, and a negative regulatory element was identified in the ZTA activation domain (39, 53). The progression from C/EBPβ to C/EBPα induction and cell cycle blockade therefore also seems to be critical in epithelial cells. In lytically induced AGS/BX1 cells, ZTA protein expression followed the induction profile of C/EBPα and was maximal at a time when C/EBPβ expression had fallen back to baseline and C/EBPβ was no longer found associated with the Zp by ChIP assay.

EBV lytic gene expression and replication take place in B cells that have differentiated towards a plasma cell phenotype (16, 35). C/EBPβ and C/EBPα are important regulators of differentiation. In the adipocyte differentiation model, C/EBPβ is expressed in response to the differentiation signal but lacks DNA binding activity. Upon entry into S phase, nuclear C/EBPβ is phosphorylated by a combination of mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Phosphorylated C/EBPβ acquires DNA binding ability and activates expression of C/EBPα and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. This regulated activity allows C/EBPβ-driven clonal expansion to precede C/EBPα-induced and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-induced exit from the cell cycle and cellular differentiation (57). C/EBPα has also been shown to be required for granulocyte and monocyte differentiation in the mouse (23). In contrast, C/EBPα appears to play a lesser role in mammary gland development. C/EBPδ and C/EBPβ are the family members involved in mammary gland involution. C/EBPδ expression is induced prior to induction of C/EBPβ, and C/EBPα does not appear to be required (24). Examination of phorbol ester- and BA-treated AGS/BX1 cells revealed a similar C/EBP induction profile to that seen in adipocyte differentiation, with C/EBPβ induction peaking prior to maximal C/EBPα induction and C/EBPβ expression subsequently being repressed. The AGS/BX1 cells do not exhibit the distinct time delay in C/EBPα induction seen in adipocyctes, presumably in part because of preexisting basal levels of C/EBPβ and C/EBPα protein expression. The data do, however, support C/EBPα induction as a factor in the linkage between lytic EBV gene expression and cell differentiation.

A comparison of the contributions of C/EBP proteins to the activation of the ZTA and RTA promoters indicated that the contribution of C/EBPs to Zp activation was more substantial than that for the Rp. Minimal C/EBPα or C/EBPβ binding to the Rp was detected in the ChIP analyses, even after chemical induction of the AGS/BX1 cells, and only weak C/EBP binding was detected to one of five potential C/EBP sites in the Rp in EMSA analyses. Examination of oriLyt showed C/EBPα and C/EBPβ binding to the oriLyt promoter, but the C/EBPα and C/EBPβ responses of this promoter in reporter assays were relatively small in comparison to ZTA induction. A previous deletional analysis of the requirement for cis-acting elements in oriLyt had found that a deletion that covered the CCAAT box and what we now recognize to be an adjacent C/EBP site in the oriLyt promoter abolished both promoter activity and oriLyt replication (54). A more defined mutation that ablated C/EBP binding but spared the CCAAT sequence of the promoter allowed us to discriminate between these two activities. Mutation of the promoter proximal O1 C/EBP site had little effect on ZTA-induced activation of the oriLyt promoter in a reporter assay but resulted in a significant loss in oriLyt replication efficiency. ZTA physically interacts with C/EBPα (69). The O1 C/EBP site is located between the ZRE1 and ZRE2 and the ZRE3 and ZRE4 pairs of ZTA binding sites in the oriLyt promoter, and contacts between DNA-bound C/EBPα and DNA-bound ZTA proteins may affect DNA conformation in a way that enhances replication competency. ZTA has been found to induce low-level replication of an oriLyt devoid of ZTA binding sites (19). Recruitment of ZTA indirectly through protein-protein interactions such as those with DNA-bound C/EBPα might be a contributing factor in this setting.

The overall importance of C/EBP proteins for induction of EBV lytic gene expression was demonstrated by the reduction in ZTA, RTA, and BMRF1 protein levels in AGS/BX1 cells transfected with CHOP10, a negative regulator of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ DNA binding ability. The mechanism of the CHOP10 effect is envisioned as follows (Fig. 9): CHOP10 negatively affects C/EBPβ induction of the C/EBPα gene and, consequently, C/EBPα protein induction of BZLF1 expression. Reduction of ZTA protein levels feeds back by reducing C/EBPα stability and C/EBPα autoinduction. Reduced levels of ZTA result in a reduction in ZTA-mediated activation of RTA and RTA autoactivation (42). Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus RTA also interacts with and increases the levels of C/EBPα (66). If EBV RTA has conserved this function, then loss of RTA would also feed back to negatively impact on C/EBPα levels. Expression of BMRF1 was dramatically impaired by CHOP10. BMRF1 is regulated by ZTA and RTA (13, 15, 28, 50, 70), and expression would be affected by the reduction in the levels of both of these proteins. In this model it is the impact of C/EBPα on induction of ZTA that is a key to the subsequent impairment of lytic gene expression by CHOP10. C/EBPα may also have a separate role in lytic EBV DNA replication, and C/EBPα is likely to be one of the cell proteins that links lytic gene expression to the differentiation state of the cell.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA30356 to S.D.H. and R01 CA73585 to G.S.H.

We thank Feng Chang for manuscript preparation, Angela Lo for NPC cell lines, Dan Lane for anti-C/EBPα antibody, and Dan Lane, Q. Q. Tang, and Jianyong Liu for valuable technical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson, A. L., D. Darr, E. Holley-Guthrie, R. A. Johnson, A. Mauser, J. Swenson, and S. Kenney. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early proteins BZLF1 and BRLF1 activate the ATF2 transcription factor by increasing the levels of phosphorylated p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases. J. Virol. 74:1224-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amon, W., U. K. Binne, H. Bryant, P. J. Jenkins, C. E. Karstegl, and P. J. Farrell. 2004. Lytic cycle gene regulation of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 78:13460-13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amon, W., and P. J. Farrell. 2005. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. Rev. Med. Virol. 15:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhende, P. M., W. T. Seaman, H. J. Delecluse, and S. C. Kenney. 2004. The EBV lytic switch protein, Z, preferentially binds to and activates the methylated viral genome. Nat. Genet. 36:1099-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binne, U. K., W. Amon, and P. J. Farrell. 2002. Promoter sequences required for reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 76:10282-10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaeser, F., N. Ho, R. Prywes, and T. A. Chatila. 2000. Ca(2+)-dependent gene expression mediated by MEF2 transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 275:197-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borras, A. M., J. L. Strominger, and S. H. Speck. 1996. Characterization of the ZI domains in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 gene promoter: role in phorbol ester induction. J. Virol. 70:3894-3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borza, C. M., and L. M. Hutt-Fletcher. 2002. Alternate replication in B cells and epithelial cells switches tropism of Epstein-Barr virus. Nat. Med. 8:594-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant, H., and P. J. Farrell. 2002. Signal transduction and transcription factor modification during reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 76:10290-10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cayrol, C., and E. K. Flemington. 1996. The Epstein-Barr virus bZIP transcription factor Zta causes G0/G1 cell cycle arrest through induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. EMBO J. 15:2748-2759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatila, T., N. Ho, P. Liu, S. Liu, G. Mosialos, E. Kieff, and S. H. Speck. 1997. The Epstein-Barr virus-induced Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase type IV/Gr promotes a Ca(2+)-dependent switch from latency to viral replication. J. Virol. 71:6560-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, H., J. M. Lee, Y. Wang, D. P. Huang, R. F. Ambinder, and S. D. Hayward. 1999. The Epstein-Barr virus latency Qp promoter is positively regulated by STATs and Zta interference with JAK-STAT activation leads to loss of Qp activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9339-9344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, L. W., P. J. Chang, H. J. Delecluse, and G. Miller. 2005. Marked variation in response of consensus binding elements for the Rta protein of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 79:9635-9650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cochet, C., D. Martel-Renoir, V. Grunewald, J. Bosq, G. Cochet, G. Schwaab, J. F. Bernaudin, and I. Joab. 1993. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus immediate early gene, BZLF1, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor cells. Virology 197:358-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Countryman, J. K., L. Heston, L. Gradoville, H. Himmelfarb, S. Serdy, and G. Miller. 1994. Activation of the Epstein-Barr virus BMRF1 and BZLF1 promoters by ZEBRA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Virol. 68:7628-7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford, D. H., and I. Ando. 1986. EB virus induction is associated with B-cell maturation. Immunology 59:405-409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.di Renzo, L., A. Altiok, G. Klein, and E. Klein. 1994. Endogenous TGF-beta contributes to the induction of the EBV lytic cycle in two Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 57:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fahmi, H., C. Cochet, Z. Hmama, P. Opolon, and I. Joab. 2000. Transforming growth factor beta 1 stimulates expression of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 immediate-early gene product ZEBRA by an indirect mechanism which requires the MAPK kinase pathway. J. Virol. 74:5810-5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feederle, R., and H. J. Delecluse. 2004. Low level of lytic replication in a recombinant Epstein-Barr virus carrying an origin of replication devoid of BZLF1-binding sites. J. Virol. 78:12082-12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feederle, R., M. Kost, M. Baumann, A. Janz, E. Drouet, W. Hammerschmidt, and H. J. Delecluse. 2000. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic program is controlled by the co-operative functions of two transactivators. EMBO J. 19:3080-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Autoregulation of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J. Virol. 64:1227-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flemington, E., and S. H. Speck. 1990. Identification of phorbol ester response elements in the promoter of Epstein-Barr virus putative lytic switch gene BZLF1. J. Virol. 64:1217-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman, A. D., J. R. Keefer, T. Kummalue, H. Liu, Q. F. Wang, and R. Cleaves. 2003. Regulation of granulocyte and monocyte differentiation by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 31:338-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimm, S. L., and J. M. Rosen. 2003. The role of C/EBPbeta in mammary gland development and breast cancer. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 8:191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruffat, H., E. Manet, and A. Sergeant. 2002. MEF2-mediated recruitment of class II HDAC at the EBV immediate early gene BZLF1 links latency and chromatin remodeling. EMBO Rep. 3:141-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris, T. E., J. H. Albrecht, M. Nakanishi, and G. J. Darlington. 2001. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-alpha cooperates with p21 to inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase-2 activity and induces growth arrest independent of DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29200-29209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann, K., P. Frangou, J. Middeldorp, and G. Niedobitek. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus replication in tongue epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2995-2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holley-Guthrie, E. A., E. B. Quinlivan, E.-C. Mar, and S. Kenney. 1990. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BMRF1 promoter for early antigen (EA-D) is regulated by the EBV transactivators, BRLF1 and BZLF1, in a cell-specific manner. J. Virol. 64:3753-3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iakova, P., S. S. Awad, and N. A. Timchenko. 2003. Aging reduces proliferative capacities of liver by switching pathways of C/EBPalpha growth arrest. Cell 113:495-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwakiri, D., and K. Takada. 2004. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a determinant of responsiveness to B cell antigen receptor-mediated Epstein-Barr virus activation. J. Immunol. 172:1561-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkins, T. D., H. Nakagawa, and A. K. Rustgi. 1997. The keratinocyte-specific Epstein-Barr virus ED-L2 promoter is regulated by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate through two cis-regulatory elements containing E-box and Kruppel-like factor motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24433-24442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraus, R. J., S. J. Mirocha, H. M. Stephany, J. R. Puchalski, and J. E. Mertz. 2001. Identification of a novel element involved in regulation of the lytic switch BZLF1 gene promoter of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 75:867-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus, R. J., J. G. Perrigoue, and J. E. Mertz. 2003. ZEB negatively regulates the lytic-switch BZLF1 gene promoter of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 77:199-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagenaur, L. A., and J. M. Palefsky. 1999. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus promoters in oral epithelial cells and lymphocytes. J. Virol. 73:6566-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laichalk, L. L., and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 2005. Terminal differentiation into plasma cells initiates the replicative cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J. Virol. 79:1296-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavens, S., E. A. Faust, F. Lu, M. Jacob, M. Leta, P. M. Lieberman, and E. Pure. 2004. Identification of protein tyrosine kinases required for B-cell-receptor-mediated activation of an Epstein-Barr Virus immediate-early gene promoter. J. Virol. 78:8543-8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang, C. L., J. L. Chen, Y. P. Hsu, J. T. Ou, and Y. S. Chang. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 gene is activated by transforming growth factor-beta through cooperativity of Smads and c-Jun/c-Fos proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23345-23357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieberman, P. M., and A. J. Berk. 1990. In vitro transcriptional activation, dimerization, and DNA-binding specificity of the Epstein-Barr virus Zta protein. J. Virol. 64:2560-2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, Z., Q. Yin, and E. Flemington. 2004. Identification of a negative regulatory element in the Epstein-Barr virus Zta transactivation domain that is regulated by the cell cycle control factors c-Myc and E2F1. J. Virol. 78:11962-11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, M. Y., Y. Y. Shih, L. Y. Li, S. P. Chou, T. S. Sheen, C. L. Chen, C. S. Yang, and J. Y. Chen. 2000. Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1 gene, a homologue of Bcl-2, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissue. J. Med. Virol. 61:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, P., S. Liu, and S. H. Speck. 1998. Identification of a negative cis element within the ZII domain of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch BZLF1 gene promoter. J. Virol. 72:8230-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu, P., and S. H. Speck. 2003. Synergistic autoactivation of the Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early BRLF1 promoter by Rta and Zta. Virology 310:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu, S., P. Liu, A. Borras, T. Chatila, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Cyclosporin A-sensitive induction of the Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle switch is mediated via a novel pathway involving a MEF2 family member. EMBO J. 16:143-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo, B., Y. Wang, X. F. Wang, H. Liang, L. P. Yan, B. H. Huang, and P. Zhao. 2005. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus genes in EBV-associated gastric carcinomas. World J. Gastroenterol. 11:629-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacCallum, P., L. Karimi, and L. J. Nicholson. 1999. Definition of the transcription factors which bind the differentiation responsive element of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 Z promoter in human epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1501-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martel-Renoir, D., V. Grunewald, R. Touitou, G. Schwaab, and I. Joab. 1995. Qualitative analysis of the expression of Epstein-Barr virus lytic genes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma biopsies. J. Gen. Virol. 76:1401-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mauser, A., E. Holley-Guthrie, D. Simpson, W. Kaufmann, and S. Kenney. 2002. The Epstein-Barr virus immediate-early protein BZLF1 induces both a G2 and a mitotic block. J. Virol. 76:10030-10037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molesworth, S. J., C. M. Lake, C. M. Borza, S. M. Turk, and L. M. Hutt-Fletcher. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus gH is essential for penetration of B cells but also plays a role in attachment of virus to epithelial cells. J. Virol. 74:6324-6332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montalvo, E. A., M. Cottam, S. Hill, and Y. J. Wang. 1995. YY1 binds to and regulates cis-acting negative elements in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J. Virol. 69:4158-4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinlivan, E. B., E. A. Holley-Guthrie, M. Norris, D. Gutsch, S. L. Bachenheimer, and S. C. Kenney. 1993. Direct BRLF1 binding is required for cooperative BZLF1/BRLF1 activation of the Epstein-Barr virus early promoter, BMRF1. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:1999-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodrigiuez, A., M. Armstrong, D. Dwyer, and E. Flemington. 1999. Genetic dissection of cell growth arrest functions mediated by the Epstein-Barr virus lytic gene product, Zta. J. Virol. 73:9029-9038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez, A., E. J. Jung, and E. K. Flemington. 2001. Cell cycle analysis of Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells following treatment with lytic cycle-inducing agents. J. Virol. 75:4482-4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodriguez, A., E. J. Jung, Q. Yin, C. Cayrol, and E. K. Flemington. 2001. Role of c-myc regulation in Zta-mediated induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27 and cell growth arrest. Virology 284:159-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schepers, A., D. Pich, J. Mankertz, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. cis-Acting elements in the lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 67:4237-4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrem, H., J. Klempnauer, and J. Borlak. 2004. Liver-enriched transcription factors in liver function and development. Part II: the C/EBPs and D site-binding protein in cell cycle control, carcinogenesis, circadian gene regulation, liver regeneration, apoptosis, and liver-specific gene regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 56:291-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takada, K., and Y. Ono. 1989. Synchronous and sequential activation of latently infected Epstein-Barr virus genomes. J. Virol. 63:445-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang, Q. Q., M. Gronborg, H. Huang, J. W. Kim, T. C. Otto, A. Pandey, and M. D. Lane. 2005. Sequential phosphorylation of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein β by MAPK and glycogen synthase kinase 3β is required for adipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9766-9771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang, Q. Q., T. C. Otto, and M. D. Lane. 2003. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta is required for mitotic clonal expansion during adipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:850-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas, C., A. Dankesreiter, H. Wolf, and F. Schwarzmann. 2003. The BZLF1 promoter of Epstein-Barr virus is controlled by E box-/HI-motif-binding factors during virus latency. J. Gen. Virol. 84:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas, J. A., D. H. Felix, D. Wray, J. C. Southam, H. A. Cubie, and D. H. Crawford. 1991. Epstein-Barr virus gene expression and epithelial cell differentiation in oral hairy leukoplakia. Am. J. Pathol. 139:1369-1380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timchenko, N. A., T. E. Harris, M. Wilde, T. A. Bilyeu, B. L. Burgess-Beusse, M. J. Finegold, and G. J. Darlington. 1997. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha regulates p21 protein and hepatocyte proliferation in newborn mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7353-7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Urier, G., M. Buisson, P. Chambard, and A. Sergeant. 1989. The Epstein-Barr virus early protein EB1 activates transcription from different responsive elements including AP-1 binding sites. EMBO J. 8:1447-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walling, D. M., C. M. Flaitz, C. M. Nichols, S. D. Hudnall, and K. Adler-Storthz. 2001. Persistent productive Epstein-Barr virus replication in normal epithelial cells in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1499-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang, H., T. Goode, P. Iakova, J. H. Albrecht, and N. A. Timchenko. 2002. C/EBPalpha triggers proteasome-dependent degradation of cdk4 during growth arrest. EMBO J. 21:930-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang, H., P. Iakova, M. Wilde, A. Welm, T. Goode, W. J. Roesler, and N. A. Timchenko. 2001. C/EBPalpha arrests cell proliferation through direct inhibition of Cdk2 and Cdk4. Mol. Cell 8:817-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, S. E., F. Y. Wu, Y. Yu, and G. S. Hayward. 2003. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-alpha is induced during the early stages of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) lytic cycle reactivation and together with the KSHV replication and transcription activator (RTA) cooperatively stimulates the viral RTA, MTA, and PAN promoters. J. Virol. 77:9590-9612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang, Y., B. Luo, L. P. Yan, B. H. Huang, and P. Zhao. 2005. Relationship between Epstein-Barr virus-encoded proteins with cell proliferation, apoptosis, and apoptosis-related proteins in gastric carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 11:3234-3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang, Y. C., J. M. Huang, and E. A. Montalvo. 1997. Characterization of proteins binding to the ZII element in the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter: transactivation by ATF1. Virology 227:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu, F. Y., H. Chen, S. E. Wang, C. M. ApRhys, G. Liao, M. Fujimuro, C. J. Farrell, J. Huang, S. D. Hayward, and G. S. Hayward. 2003. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α interacts with ZTA and mediates ZTA-induced p21CIP-1 accumulation and G1 cell cycle arrest during the Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle. J. Virol. 77:1481-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, F. Y., S. E. Wang, H. Chen, L. Wang, S. D. Hayward, and G. S. Hayward. 2004. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α binds to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) ZTA protein through oligomeric interactions and contributes to cooperative transcriptional activation of the ZTA promoter through direct binding to the ZII and ZIIIB motifs during induction of the EBV lytic cycle. J. Virol. 78:4847-4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yin, Q., K. Jupiter, and E. K. Flemington. 2004. The Epstein-Barr virus transactivator Zta binds to its own promoter and is required for full promoter activity during anti-Ig and TGF-beta1 mediated reactivation. Virology 327:134-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Young, L. S., R. Lau, M. Rowe, G. Niedobitek, G. Packham, F. Shanahan, D. T. Rowe, D. Greenspan, J. S. Greenspan, A. B. Rickinson, et al. 1991. Differentiation-associated expression of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 transactivator protein in oral hairy leukoplakia. J. Virol. 65:2868-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zalani, S., E. Holley-Guthrie, and S. Kenney. 1996. Epstein-Barr viral latency is disrupted by the immediate-early BRLF1 protein through a cell-specific mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9194-9199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, J. W., Q. Q. Tang, C. Vinson, and M. D. Lane. 2004. Dominant-negative C/EBP disrupts mitotic clonal expansion and differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:43-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]