Abstract

The 2A proteinases (2Apro) from the picornavirus family are multifunctional cysteine proteinases that perform essential roles during viral replication, involving viral polyprotein self-processing and shutting down host cell protein synthesis through cleavage of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) proteins. Coxsackievirus B4 (CVB4) 2Apro also cleaves heart muscle dystrophin, leading to cytoskeletal dysfunction and the symptoms of human acquired dilated cardiomyopathy. We have determined the solution structure of CVB4 2Apro (extending in an N-terminal direction to include the C-terminal eight residues of CVB4 VP1, which completes the VP1-2Apro substrate region). In terms of overall fold, it is similar to the crystal structure of the mature human rhinovirus serotype 2 (HRV2) 2Apro, but the relatively low level (40%) of sequence identity leads to a substantially different surface. We show that differences in the cI-to-eI2 loop between HRV2 and CVB4 2Apro translate to differences in the mechanism of eIF4GI recognition. Additionally, the nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation properties of CVB4 2Apro, particularly of residues G1 to S7, F64 to S67, and P107 to G111, reveal that the substrate region is exchanging in and out of a conformation in which it occupies the active site with association and dissociation rates in the range of 100 to 1,000 s−1. This exchange influences the conformation of the active site and points to a mechanism for how self-processing can occur efficiently while product inhibition is avoided.

Members of the picornavirus family include several common and important pathogens of humans, e.g., poliovirus, hepatitis A virus, rhinovirus (common cold), and coxsackievirus. Infection of heart muscle myocytes with coxsackie B viruses (members of the genus Enterovirus) is a significant etiological agent of human acquired dilated cardiomyopathy, being recognized in 30% of patients (1, 50). The disease is characterized by cardiac enlargement and congestive heart failure, and the pathological mechanism involves proteolytic cleavage by enteroviral 2A proteinases (2Apro) of dystrophin (in the hinge-3 region) (2), leading to the disruption of the extrasarcomeric cytoskeleton and loss of transmission of mechanical force to the extracellular matrix (13, 54). The subsequent increased cell membrane permeability may facilitate effective release of new enterovirus particles from infected myocytes (61). The central role that dystrophin plays in the etiology of dilated cardiomyopathy (2, 3) is also substantiated in hereditary forms of the disease (Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy and X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy), which are characterized by mutations in the dystrophin gene (27, 33, 39, 55).

The genomes of the picornaviruses consist of single-stranded, messenger sense RNA molecules (7,500 nucleotides), which act as templates for both genomic replication and protein synthesis (see reference 32 and references therein). A polyprotein precursor is synthesized from the single open reading frame contained within the genome (Fig. 1), which is processed during translation by viral proteinases. The 2Apro cleaves intramolecularly between the C terminus of VP1 and its own N terminus (56), termed the VP1-2Apro substrate region, separating the capsid protein precursor from the nonstructural protein precursor. All remaining cleavages are performed by the 3C proteinase or its precursor, 3CD proteinase (see reference 51 and references therein), yielding the mature viral proteins. The 2Apro is a multifunctional enzyme which, in addition to viral polyprotein processing and dystrophin cleavage, plays an important role in shutting down the host's cellular metabolism in order to achieve optimum viral replication. The major cellular proteolysis targets of 2Apro during the early stages of enteroviral and rhinoviral infection are eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) eIF4GI and eIF4GII. The eIF4G proteins, together with the cap-binding protein of cellular mRNAs (eIF4E) and the ATP-dependent RNA helicase (eIF4A), form the eIF4F complex responsible for the recruitment of capped mRNAs to the ribosome (for reviews, see references 25, 42, and 46). Cleavage of the eIF4G proteins by 2Apro abolishes their scaffolding function within the eIF4F complex and between the eIF4F complex and part of the small ribosomal subunit (eIF3) (30), leading to the failure of translation initiation of cellular capped mRNAs (i.e., host cell shutoff) (17, 22). However, protein translation of picornaviral uncapped RNA remains unaffected or even stimulated by cleavage of eIF4GI and eIF4GII, since initiation occurs directly at the internal ribosomal entry sequence contained in the 5′-nontranscribed region of the RNA genome (7). A second mechanism for the shutoff of host cell protein synthesis may also occur (26), involving the proteolytic cleavage by coxsackievirus 2Apro of cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein, which mediates the translation initiation of eukaryotic mRNAs containing 3′-terminal poly(A) tracts.

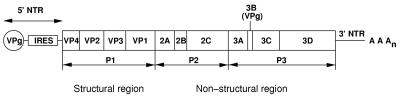

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the picornaviral RNA genome. Genes for the following proteins are indicated. VP1 to VP4 are capsid proteins; 2Apro and 3Cpro are proteinases responsible for proteolytic processing; 2B, 2C, and 3A are core proteins; VPg (genome-linked protein) is covalently attached to the 5′ end of the RNA; and 3Dpol is the RNA-directed RNA polymerase. Prior to the completion of protein synthesis, the primary intramolecular proteolysis event is performed by 2Apro, which cleaves between the C terminus of VP1 and its own N terminus, thereby separating the structural (capsid) protein precursor (P1) from the nonstructural protein precursor (P2 and P3). All subsequent proteolytic processing steps are performed by 3Cpro or its precursor, 3CDpro. The internal ribosome entry sequence (IRES) contained within the 5′-nontranscribed region (NTR) is responsible for recruiting ribosomes to the viral RNA prior to protein synthesis via the cap-independent translation pathway.

A structural model of proteolytic cleavage by 2A proteinases was proposed based on a 1.95-Å-resolution crystal structure of 2Apro from human rhinovirus serotype 2 (HRV2) (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession no. 2HRV) (43). Intramolecular cleavage from VP1 had taken place prior to crystallization, and thus the structure represents the enzyme in the form that is active against the eIF4G proteins. This structure identifies 2A proteinases as members of the chymotrypsin-related protease family (the PA family of proteases) and comprises a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet as the N-terminal domain and a larger C-terminal domain containing a six-stranded antiparallel β-barrel. The HRV2 2Apro fold also contains a structural zinc ion coordinated tetrahedrally by three cysteine sulfur atoms and one histidine nitrogen atom. The zinc ion is tightly bound, and it can only be removed via chelation with EDTA upon denaturation of HRV2 2Apro at low pH or at elevated temperature (53). The active site is located in the cleft between the two domains and consists of a catalytic triad involving His-18 (general base), Asp-35, and Cys-106 (nucleophile). The N terminus of HRV2 2Apro, the P′ product of the intramolecular cleavage reaction, is no longer within the active site but packs against the C-terminal domain distant from the active site cleft.

In the present study, we have determined the three-dimensional (3D) solution structure of the 19-kDa 2Apro (EC 3.4.22.29) from coxsackievirus serotype B4 (CVB4) (strain JVB/Benschoten/New York/51). The protein employed comprises the last eight residues of CVB4 capsid protein VP1 (residues 274 to 281) positioned N terminally to the CVB4 2Apro sequence (residues 1 to 150) (52) and thus represents CVB4 2Apro prior to intramolecular cleavage within the VP1-2Apro substrate region. In addition, a single-amino-acid mutation at the catalytic cysteine nucleophile (C110A) was introduced to inactivate the 2Apro as a proteinase in order to prevent self-cleavage. A BLAST alignment of 40 picornaviral 2A proteinase sequences indicates that CVB4 2Apro and HRV2 2Apro represent two extremes in the primary sequence diversity of the 2Apro family. They share a relatively low (40%) level of amino acid sequence identity, leading to substantially different surface characteristics. In order to test our hypothesis that the mechanism of eIF4GI recognition by CVB4 2Apro and HRV2 2Apro is driven by different surface properties, we designed rationally a CVB4 2Apro variant with improved eIF4GI cleavage efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid preparation, protein expression, and purification.

A DNA construct corresponding to an N-terminal polyhistidine sequence (His6), the C-terminal eight amino acids of CVB4 VP1 (i.e., residues 274 to 281 [ERASLITT]), and CVB4 2Apro containing a single-amino-acid mutation at the active site nucleophile (C110A) was cloned directionally between NcoI and BamHI restriction sites into a pET3d expression vector (Novagen). Following DNA sequence verification, Escherichia coli strain BL2(DE3) pLysE (Novagen) was transformed with the ligated vector pET3d/CVB4 2Apro. Expression of CVB4 2Apro was performed at 25°C in M9 minimal media containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 32 μg/ml chloramphenicol and was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). For 15N and 15N/13C uniformly labeled CVB4 2Apro samples, 1 g (15NH4)2SO4 per liter minimal medium and 1 g (15NH4)2SO4 and 3 g [13C6]glucose per liter minimal medium were used as the sole carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. For the fractionally 13C-labeled sample, the carbon source in the minimal media contained both [13C6]glucose and unlabeled glucose, mixed in a 1:9 ratio.

For protein purification, the cleared cell lysate in buffer A (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) was applied to a DEAE-Sepharose fast-flow ion exchange column (Amersham Biociences) and CVB4 2Apro was eluted from the column at 300 to 350 mM NaCl by use of a gradient (50 mM to 600 mM NaCl in buffer A). Fractions containing CVB4 2Apro were pooled, an equal volume of 4 M ammonium sulfate was added to precipitate the proteinase, and the insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation. The pellet was carefully suspended in 2 to 4 ml of buffer B (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.1, 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), in which the proteinase remained insoluble and was collected by centrifugation. Addition of a further 2 ml of buffer B to the pellet rendered the protein soluble (through further dilution of the remaining ammonium sulfate). Residual insoluble residue was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was applied to a Superdex-200 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences). CVB4 2Apro eluted as a sharp peak with a molecular mass of 19 kDa, corresponding to a monomer. The presence of the structural zinc ion following purification was determined using a Perkin Elmer Elan 6100 inductively coupled plasma (ICP) mass. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) samples were prepared by combining fractions containing CVB4 2Apro and were concentrated using a Vivaspin concentrator (Vivascience) up to 250 to 500 μM (determined by the Bradford assay [7a]) in 50 mM potassium phosphate, 5 to 10 mM DTT, pH 7.6, 10% 2H2O-90% H2O (or 99.9% 2H2O). The NMR samples were estimated to be greater than 95% pure based on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). All protein purification steps and sample storage were performed at room temperature, as CVB4 2Apro was found to be susceptible to cold denaturation.

NMR spectroscopy.

NMR spectra of CVB4 2Apro were acquired at a sample temperature of 303 K with a Bruker DRX series 500-MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm triple-resonance cryoprobe and pulsed-field gradients, except where indicated otherwise. Proton chemical shifts were referenced to TSP [sodium 3-trimethylsilyl-2,2,3,3-(2H4) propionate] at 0.0 ppm. 15N and 13C chemical shifts were calculated relative to TSP by use of the gyromagnetic ratios of 15N, 13C, and 1H nuclei [γ(15N)/γ(1H) = 0.101329118; γ(13C)/γ(1H) = 0.251449530]. Resonance assignments for the HN, N, Cα, C′, Cβ, and Hα nuclei were obtained from HNCA (23), HNCO (23), HN(CA)CO (14), CBCA(CO)HN (24), and HNCACB (Bruker DRX series 800-MHz spectrometer) (60) heteronuclear triple-resonance experiments and a 60-ms-mixing-time, 15N-edited, total correlated spectroscopy-heteronuclear single quantum correlation (TOCSY-HSQC) (12) spectrum. Aliphatic side chain resonance assignment of 13C and 1H nuclei beyond the Cβ position was completed using HCCH- and CCH-TOCSY (6) and constant-time 13C-HSQC (58) spectra recorded for CVB4 2Apro in 99.9% 2H2O. Aromatic side chain assignment was performed using constant-time 13C-HSQC optimized for aromatic couplings and 15N-filtered homonuclear TOCSY spectra (59), in conjunction with the simultaneously acquired 15N- and 13C-edited 3D nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) spectrum (100-ms mixing time) (41) used for obtaining nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) for the structure calculations. Stereospecific assignments of resolvable valine and leucine methyl groups were obtained using a 10% 13C-labeled CVB4 2Apro sample as described previously (37), with a Bruker DRX series 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with triple-axis gradients and a triple-resonance probe head. All spectra were processed and analyzed with Silicon Graphics workstations by use of FELIX 2000 software (Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Structure determination.

Sequence-specific assignments were obtained using the simulated annealing Monte Carlo algorithm Asstools (45). The assignment of 1H, 15N, and 13C nuclei was nearly complete for CVB4 2Apro (residues 1 to 150); the levels of unambiguously assigned resonances were 78% of the total number of 1H nuclei in the proteinase, 81% of the 15N nuclei in backbone amide groups, and 83% of the total number of 13C nuclei. 1H-15N HSQC peaks corresponding to the remaining backbone amide groups were not observable. This is the result of exchange broadening and/or solvent exchange rather than a residual level of intramolecular proteolysis, since resonances from residues for which no 1H-15N HSQC peaks were observable were present in 1H-13C HSQC spectra, and the molecular weight was unaltered over the course of NMR data collection, as determined by SDS-PAGE. Resolvable stereospecific assignments were obtained for 20 out of 22 leucine methyl resonances and 28 out of 34 valine methyl resonances. 1H and 15N resonance assignments for the labile side chain groups were not obtained, primarily due to solvent exchange at the relatively high pH of the system (pH 7.6). For residues P73, P79, and P91, the X-Pro peptide bond adopts a trans-conformation, as evidenced by the presence of strong Hα-Hδ NOEs (no assignments were obtained for residues P2 or P107).

NOEs were assigned and distance restraints were derived from a simultaneously acquired 15N- and 13C-edited 3D NOESY spectrum (100-ms mixing time) by use of FELIX 2000, in-house macros, and UNIX scripts. Sequence-specific assignments were independently confirmed by sequential and medium-range NOE patterns. NOE cross-peak intensities were calibrated on the basis of a survey of covalently fixed distances and divided into two groups with upper bounds of 3.5 Å and 5.0 Å. Dihedral restraints were obtained from backbone and Cβ chemical shifts by use of TALOS (15) and were implemented with a range of ±2 standard deviations from the predicted dihedral angle. Hydrogen bond restraints (dN-O = 2.6 to 3.2 Å; dHN-O = 1.7 to 2.3 Å) were included for slowly exchanging backbone amides together with amide resonances within areas of regular secondary structure identified on the basis of backbone NOE patterns and by comparison with the HRV2 2Apro structure (43).

Initial structure calculations were performed without zinc ion restraints for residues 1 to 150 of CVB4 2Apro, using the dynamic annealing protocol provided with CNS version 1.1 (10). The expected zinc ion coordination site, comprising residues C56, C58, C116, and H118, adopted an approximate tetrahedral geometry in the absence of any explicit restraints to a zinc ion. In a subsequent refinement step, the zinc ion was incorporated into the structure calculations by employing appropriate covalent distance restraints [Cys(Sγ)-Zn ∼ 2.3 Å; His(Nδ1)-Zn ∼ 2.1 Å] and angle restraints [Cys(Sγ)-Zn-Cys(Sγ) ∼ 109°; His(Nδ1)-Zn-Cys(Sγ) ∼ 109°; Cys(Cβ)-Cys(Sγ)-Zn ∼ 109°; His(Cγ)-His(Nδ1)-Zn ∼ 120°] (40). One hundred structures were annealed from randomized starting coordinates, refined, and further refined incorporating the zinc ion into the structure. The 17 lowest energy structures were chosen to represent the structural ensemble.

Spin relaxation and amide exchange experiments.

Longitudinal 15N relaxation times (T1), transverse 15N relaxation times (T2), and heteronuclear steady-state 15N-{1H} NOE values were obtained using pulse sequences already described (28). Relaxation delays of 40, 80, 120, 180, 250, 500, 800, and 1,200 ms were used to calculate T1, and delays of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 130, 160, and 180 ms were used to calculate T2. For the 15N-{1H} NOE measurement, two interleaved two-dimensional spectra were acquired, with a relaxation delay of 3.0 s between scans. Relaxation parameters were determined by fitting peak intensities measured using FELIX 2000 software. Hydrogen-deuterium amide exchange was initiated by diluting uniformly 15N-labeled CVB4 2Apro (ca. 600 μM in 50 mM potassium phosphate, 10 mM DTT, pH 7.6, in 10% 2H2O-90% H2O) with an equal volume of identical buffer prepared in 99.9% 2H2O. The sample was equilibrated in the spectrometer at 303 K for 6 min prior to a series of 20 1H-15N HSQC spectra being recorded over a duration of 24 h. Slowly exchanging amide groups were identified by fitting peak intensities, measured using FELIX 2000 software, to a single exponential function.

Molecular modeling.

A model of CVB4 2Apro with the VP1-2Apro substrate region bound into the active site cleft was generated by first threading the wild-type CVB4 2Apro sequence (residues 1 to 150) onto the backbone coordinates of HRV2 2Apro (2HRV molecule A) (43) by using XPLOR version 3.1 (9). The model was then modified to include the C-terminal eight residues of CVB4 VP1 (ERASLITT), covalently attached at the proteinase N terminus by addition of residues with random coordinates. For the docking of the VP1-2Apro substrate region into the 2Apro active site, a list of close contacts between residues of the substrate and proteinase was derived based on both the crystal structure of the Streptomyces griseus protease B turkey ovomucoid (third domain) inhibitor complex (44) (PDB accession no. 3SGB) and the model of HRV2 2Apro binding an oligopeptide substrate (43). The identified close contacts between residue side chains were translated into ambiguous distance restraints (to include all side chain hydrogens) with upper bounds of 4.0 Å. Additionally, five similarly identified hydrogen bond restraints were included (dN-O = 2.6 to 3.2 Å; dHN-O = 1.7 to 2.3 Å). The docking was carried out using the dynamic annealing protocol of CNS version 1.1 (10), in which the coordinates of ERASLITT and the first eight residues of the proteinase were allowed to move, while the coordinates of CVB4 2Apro (residues 9 to 150) remained fixed. Twenty structures were generated, and the structure closest to the average coordinates was selected as representative.

In vitro analysis of 2Apro self-processing and eIF4GI cleavage.

In order to probe 2Apro self-processing and eIF4GI cleavage, two further plasmid constructs were prepared: (i) CVB4 VP1-2Apro, which contains the CVB4 nucleotides 2449 to 3741, encodes all of VP1 followed by all of 2Apro, terminating with two stop codons, and (ii) HRV2 VP1-2Apro, which contains the HRV2 nucleotides 2318 to 3586, encodes all but the first two amino acids of VP1 followed by all of 2Apro, terminating with two stop codons. In addition, CVB4 VP1-2Apro was mutated to carry a single-amino-acid mutation in 2Apro (R20L). The VP1-2Apro nucleotides were cloned downstream of the encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry sequence in the plasmid pCITE (Novagen). Following linearization with BamHI, mRNA was transcribed in vitro from CVB4 VP1-2Apro, CVB4 VP1-2Apro R20L, and HRV2 VP1-2Apro and translated in vitro in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRLs) as described previously (20, 21). The in vitro translation reactions (typically 50 μl) contained 70% RRL (Promega), 20 μCi of [35S]methionine label (1,000 Ci/mmol; Hartmann Analytic), 0.8 U of RNasin/μl, and unlabeled amino acids (except methionine) at 20 μM. After preincubation for 2 min at 30°C, translation was initiated by the addition of CVB4 VP1-2Apro, CVB4 VP1-2Apro R20L, or HRV2 VP1-2Apro mRNA to a final concentration of 10 ng/μl. Aliquots were taken at designated time points and placed on ice, and translation was terminated by the addition of unlabeled methionine and cysteine to a 2-mM concentration each, followed by Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and examined either by fluorography (17.5% acrylamide) to detect the radiolabeled translation products or by immunoblotting (6% acrylamide) with an antibody against the N terminus of eIF4GI to monitor the status of endogenous eIF4GI in the RRL.

Protein structure accession number.

The coordinates of the 17 lowest energy structures chosen to represent the structural ensemble have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession no. 1Z8R.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Solution structure of CVB4 2Apro.

The three-dimensional solution structure of CVB4 2Apro (residues 1 to 150) was determined by multidimensional heteronuclear NMR methodology using a total of 1,857 experimentally determined restraints (Table 1), comprising 1,577 unambiguous NOE distance restraints, 168 dihedral angle restraints, and 56 × 2 hydrogen bond restraints. A high density of NOE restraints is present over a broad range of the primary sequence (Fig. 2), and in overall terms, the fold is well defined but with an unrestrained protein backbone for both termini and for two internal segments (Fig. 3). The per-residue root mean square (RMS) deviations from the average structure for the backbone atoms are included in Fig. 2. The regions that are less well defined correspond primarily to residues for which no sequence-specific resonance assignments could be identified, specifically for residues comprising the N-terminal polyhistidine sequence (His6), the eight C-terminal residues of VP1, and the CVB4 2Apro segments G1 to S7, F64 to S67, and P107 to G111 (Fig. 4). For these residues, peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum and the 15N-edited 3D spectra employed for backbone sequential assignment were reduced in intensity beyond detection.

TABLE 1.

CVB4 2Apro structural parametersa

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Experimentally determined restraints | |

| Unambiguous distance restraints | |

| Total | 1,577 |

| Intraresidue | 678 |

| Sequential | 335 |

| Medium range | 95 |

| Long range (Δ > 4) | 469 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | 168 |

| Hydrogen bond restraints | 56 × 2 |

| Stereospecific valine and leucine methyl groups | 48/56 |

| Nonexperimental restraints | |

| Zn2+ protein bond restraints | 4 |

| Zn2+ protein angle restraints | 16 |

| Deviations from the experimental restraintsb | |

| NOE violations > 0.16 Å | 2 |

| Dihedral restraint violations > 2.5° | 3 |

| Mean RMS deviations from idealized geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.00178 ± 0.00004 |

| Angle geometry (°) | 0.350 ± 0.007 |

| Improper geometry (°) | 0.213 ± 0.009 |

| RMS deviations from the mean structure for well-defined regionsc(Å) | |

| Backbone heavy atoms | 0.47 |

| All heavy atoms | 1.03 |

| Ramachandran analysisd | |

| Most favored regions (%) | 78 |

| Additionally allowed regions (%) | 18 |

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 3 |

| Disallowed regions (%) | 1 |

Ensemble of the 17 lowest energy structures out of a total of 100 calculated structures.

RMS NOE violation, 0.0119±0.0004 Å; RMS dihedral violation, 0.45°±0.03°.

Residues 10 to 62, 70 to 102, and 112 to 147 (selected to exclude regions with low restraint densities [see Fig. 2]).

PROCHECK NMR (31) analysis of the structural ensemble. The percentages derived for the generously allowed and disallowed regions correspond to those residues that are ill defined or in loops in the structural ensemble (i.e., G1 to S7, F64 to S67, and P107 to G111).

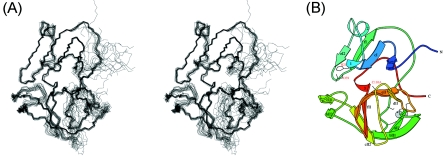

FIG. 2.

Structural parameters for CVB4 2Apro. (A) Distribution (number [No.]) of NOE restraints by residue. From bottom to top, intraresidue (white), sequential (light gray), medium-range (dark gray), and long-range (black) NOEs, respectively. (B) RMS deviations (RMSD) from the average structure for backbone atoms N, Cα, and C′, plotted as separate data points for each residue. The arrows and bars along the top of the figure represent the regions of secondary structure. β-Strands of the N domain (I) are labeled b2, c, e2, and f, whereas those of the C domain (II) are labeled a, b1, b2, c1, c2, d, e, and f. Helical structures are labeled 1, 2, and 3.

FIG. 3.

3D backbone structure and topology of CVB4 2Apro. (A) Stereoview overlay of the 17 lowest energy structures comprising the structural ensemble. The overlay was performed using the backbone atoms (N, Cα, and C′) of residues 10 to 62, 70 to 102, and 112 to 147. (B) MOLSCRIPT (29) diagram of the representative structure of CVB4 2Apro, shown in the same orientation as for panel A. β-Strands in the N domain (bI2, cI, eI2, and fI) and in the C-terminal domain (aII, bII1, bII2, cII1, cII2, dII, eII, and fII) are labeled following the nomenclature adopted by Petersen et al. (43). The regions exhibiting a helical structure are labeled 1, 2 (α-helix between strands cI and eI2), and 3. The residues comprising the catalytic triad (H21, D38, and C110A) and those involved in zinc ion coordination (C56, C58, C116, and H118) are depicted as wire frames, and the zinc ion is shown as a gray sphere.

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignment of CVB4 and HRV2 2A proteinases, including their respective C-terminal VP1 sequences. The position of the scissile bond between the C terminus of VP1 and the N terminus of 2Apro, present in the wild-type system, is indicated by an asterisk. Residues of the catalytic triad are boxed by solid lines (in this study, CVB4 2Apro carries a single-amino-acid mutation, C110A, which inactivates the enzyme), and residues that coordinate the zinc ion are boxed by dotted lines. Secondary-structure elements are indicated by arrows (β-strands) and bars (helical regions) and are labeled according to the scheme adopted by Petersen et al. (43). Horizontal dotted lines indicate contiguous residues of CVB4 2Apro for which peaks were reduced in intensity beyond detection in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum.

The nomenclature used to label the β-strands in the structure of CVB4 2Apro (Fig. 3 and 4) follows that adopted for HRV2 2Apro (43), which is based on the topology of a member of the chymotrypsin family of serine proteases that shares a significant fold similarity with that of the picornaviral 2Apro family (Streptomyces griseus protease B [PDB accession no. 3SGB]) (44). The structure of CVB4 2Apro consists of an N domain containing a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (β-strands V10 to V12 [bI2], Y15 to N19 [cI], W33 to D35 [eI2], and L40 to T44 [fI]) and a C domain comprising a six-stranded antiparallel β-barrel (β-strands T60 to F64 [aII], H71 to E77 [bII1], V98 to T102 [cII2], I113 to R115 [dII], V120 to G127 [eII], and V131 to D136 [fII]) connected together by a long interdomain loop (residues T46 to R55). Additionally, within the C domain, two β-strands (residues L81 to V84 [bII2] and R93 to S96 [cII1]) form an antiparallel β-hairpin (Fig. 3B, middle left), which makes close contact with residues from the N domain and was previously named the dityrosine flap (43). A β-bulge occurs at residues T125 and M126 on strand eII, which form hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen atom of G133. Three helical regions have been identified in the structure. A helical turn (α1; residues R20 to L22) follows β-strand cI, and a short α-helix (α2; residues H25 to Q29) lies between β-strands cI and eI2. Finally, close to the C terminus, a one-turn helix (α3; residues V137 to D139) is present. The hydrophobic core of CVB4 2Apro is composed almost exclusively of aliphatic hydrophobic residues (valine, leucine, and isoleucine). Unusually, the majority of aromatic residues are exposed on the surface: 8 of 9 Tyr residues, 2 of 4 Phe residues, 2 of 3 Trp residues, and 7 of 7 His residues.

Four highly conserved residues present in all members of the picornaviral 2Apro family serve to coordinate a very tightly bound zinc ion, which is required for the formation of enzymatically active proteinases (53, 57). The presence of zinc in CVB4 2Apro following purification was confirmed using ICP mass spectrometry. The tetrahedral coordination site for the zinc ion within CVB4 2Apro was apparent without the explicit inclusion of the metal ion in the structure calculation and comprises three cysteine sulfur atoms and one histidine nitrogen atom. Two of the ligands [C56(Sγ) and C58(Sγ)] are donated from the end of the interdomain loop (Fig. 3B), whereas the other two ligands [C116(Sγ) and H118(Nδ1)] are provided by a tight hairpin loop between β-strands dII and eII in the C domain. The subsequent incorporation of the tetrahedrally coordinated zinc ion into the CVB4 2Apro structure by use of covalent distance and angle restraints was readily accommodated without major perturbations of the protein backbone.

The residues of the catalytic triad are found in the cleft formed between the N domain and the C domain (Fig. 3). The general base (H21) lies in a helical turn (α1) following β-strand cI, and D39 projects from a loop formed between β-strands eI2 and fI. The nucleophile (replaced by A110 in this CVB4 2Apro construct) is contained in a highly conserved amino acid sequence (PGDCGG) that forms a loop (termed the “active site loop”) between β-strands cII2 and dII in the C domain. However, this sequence is one of the unrestrained segments (P107 to G111) and therefore the precise geometrical relationship that this loop makes with the other structurally well-defined members of the catalytic triad cannot be determined.

Comparison with the HRV2 2Apro structure.

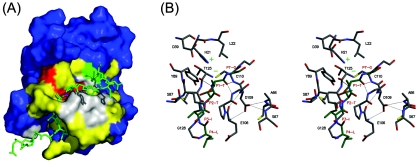

CVB4 2Apro and HRV2 2Apro share approximately 40% sequence identity (Fig. 4). A pairwise backbone atom overlay (N, Cα, C′, and O) of residues located in well-characterized structural segments of HRV2 2Apro with members of the CVB4 2Apro structural ensemble shows that the structures align closely (Fig. 5). The average pairwise RMS deviation for well-defined regions (Fig. 5) is 2.14 ± 0.06 Å, which is in the range typically found for the comparison of solution and crystal structures. The position and coordination of the zinc ion within the CVB4 2Apro structure also match the equivalent situation in HRV2 2Apro. Apart from the termini and the two unrestrained loops, the major differences between the two 2Apro structures occur within residues L22 to V32 of the N domain (L19 to I28 in HRV2 2Apro) (region I) and residues Q85 to P91 of the C domain (Q81 to P87 in HRV2 2Apro) (region II). For CVB4 2Apro, region I adopts a well-characterized α-helix (α2) and contains an additional amino acid (H25) compared to the HRV2 2Apro sequence (Fig. 4). In HRV2 2Apro, the equivalent region I displays high-temperature factors for both molecules A and B in the asymmetric unit (PDB accession no. 2HRV) (43). Upon superimposing molecules A and B of HRV2 2Apro, for residues 1 to 139 the RMS deviation is 1.2 Å and the largest conformational difference between the two forms locates to region I. In molecule A this region adopts a short 310-helix, and in molecule B it is an unstructured loop translated by up to 6 Å from the atom positions defined for molecule A. Region II includes the β-hairpin loop between strands bII2 and cII1 (the dityrosine flap), which for HRV2 2Apro in the crystal has the least well defined electron density and exhibits the highest temperature factors.

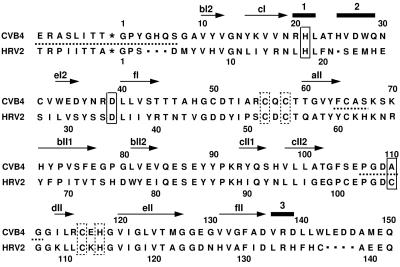

FIG. 5.

Comparison of CVB4 2Apro and HRV2 2Apro structures. Stereo backbone traces (A and B) showing the overlay of two representative members of the CVB4 2Apro NMR structural ensemble (red and magenta) together with molecule A of the HRV2 2Apro crystal structure (black). The representative structures of CVB4 2Apro were chosen to illustrate the extremes of backbone positioning for the region P107 to G111. The overlay was performed with MIDAS (18) by using the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C′, and O) for residues in well-characterized structural segments (for CVB4 2Apro, residues 10 to 21, 33 to 62, 70 to 84, 92 to 101, and 113 to 141, and for HRV2 2Apro, residues 7 to 18, 29 to 58, 66 to 80, 88 to 97, and 109 to 137). The pairwise RMS deviations between the CVB4 2Apro and HRV2 2Apro structures are 2.13 Å (red-black) and 2.19 Å (magenta-black). In panel A, the orientation of the figure is identical to that presented in Fig. 3, whereas in panel B the molecule has undergone a rotation of 90 degrees about the vertical axis. Electrostatic potential surface representations of (C) CVB4 2Apro and (D) HRV2 2Apro are shown, oriented as in panel B. The surface was generated using GRASP (38), with limiting values of ±10.

Mobility within the CVB4 2Apro structure.

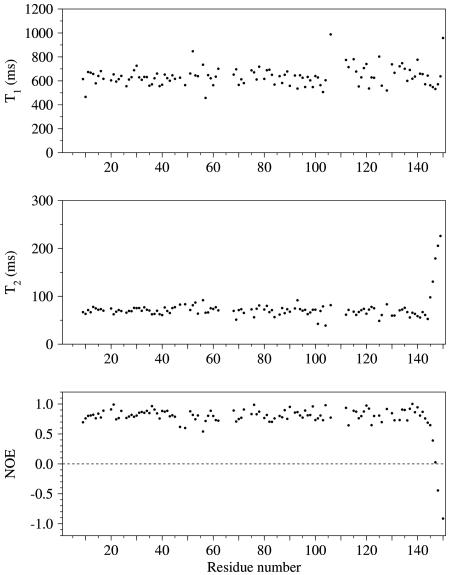

In order to determine whether the differences between the structures of HRV2 2Apro and CVB4 2Apro are the result of motion within these regions, the mobility of the backbone of CVB4 2Apro was characterized by measuring 15N T1 and T2 relaxation times and heteronuclear steady-state 15N-{1H} NOE values for backbone nitrogen atoms (Fig. 6). The correlation time for CVB4 2Apro was calculated to be approximately 11 ns. The 15N relaxation data demonstrate that CVB4 2Apro has unusually little internal motion on a subnanosecond timescale over essentially the whole length of the protein, except for the C-terminal five residues, indicating that the structure is very tightly packed, even in the loops between secondary-structure elements. This lack of mobility is in part conferred by the shortness of loops, which is a common feature of picornaviral proteinases (49). The tight packing includes both regions I and II with high-temperature factors in HRV2 2Apro (43). Hence, the variation in conformation of HRV2 2Apro in these regions is not reflected in high frequency flexibility within CVB4 2Apro.

FIG. 6.

15N T1 and T2 relaxation times and heteronuclear steady-state 15N-{1H} NOE values by residue for backbone nitrogen atoms in CVB4 2Apro.

More apparent within the NMR relaxation behavior is the presence of conformational dynamics on a longer timescale, in the millisecond range, which results in the reduction of NMR signal intensity in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum beyond the limits of detection for residues within the VP1-2Apro substrate region, the active site loop (P107 to G111) and its neighboring hairpin loop (F64 to S67) (Fig. 4), and residues N19, Q85, and L114. Additionally, ca. 30 residues, present mainly in the C domain, display significant reductions in 1H-15N HSQC peak intensity. These intensity reductions are not the result of rapid exchange between amide hydrogens and the solvent. Although solvent exchange is observed for a few residues with high surface exposure, it is restricted only to those that have very high intrinsic exchange rates. Confirmation that low-frequency dynamics rather than amide solvent exchange is the primary cause of intensity reduction is provided by equivalent line-broadening effects being observable for some carbon-bound hydrogen resonances within the VP1-2Apro substrate region and segments P107 to G111 and F64 to S67.

The line-broadening behavior is indicative of a conformational dynamics process occurring between two (or more) similarly populated forms. The effects on the NMR signals of residues immediately flanking the regions where no signal intensity can be observed provide indications of the timescale of the conformational dynamics. The lack of a significant effect on 15N T2 rates in the flanking regions (Fig. 6) indicates that the dynamics are faster than the chemical shift differences of 15N resonances in the relevant conformations. In contrast, there is widespread perturbation of 1H resonances in flanking regions, indicating that the difference in 1H chemical shift between conformations is similar to the frequency of the conformational dynamics (i.e., the intermediate exchange regime for 1H). Most of the differences in 1H chemical shifts between the interconverting conformations would fall in the range of 0.2 to 2.0 ppm, which equates to the conformational dynamics occurring in a frequency range of 100 to 1,000 s−1.

Sources of conformational exchange dynamics.

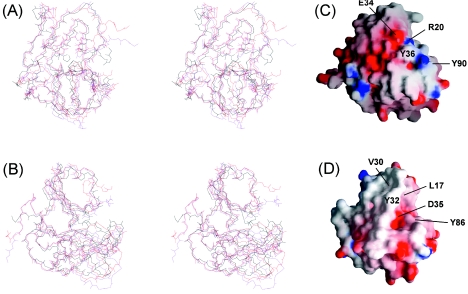

The most likely source of the low-frequency dynamics is the exchange of the VP1-2Apro substrate region in and out of the active site cleft. However, the widespread distribution of the resonance intensity reductions (Fig. 7A) indicates that the perturbations are not limited to the immediate site of contact between the substrate and the cleft. Additionally, the regions showing resonance intensity reductions are not uniformly distributed around the active site cleft. The dityrosine flap region (residues Q85 to K92) on one side of the substrate-binding cleft (Fig. 7A, middle left) is affected only to a moderate extent by the conformational exchange process, whereas a far larger perturbation is observed to occur in the active site loop (P107 to G111), which contains the active site nucleophile (alanine substituted in the present case, i.e., A110), and its adjacent hairpin loop (residues F64 to S67).

FIG. 7.

Model of the VP1-2Apro substrate region bound in the active site of wild-type CVB4 2Apro. (A) The VP1 C-terminal sequence ERASLITT, which is covalently attached at the N terminus of CVB4 2Apro, together with the first eight residues of the proteinase (GPYGHQSG), is shown as a green wireframe. The scissile bond is shown in purple. The CVB4 2Apro structure (residues 9 to 150) is depicted as a solvent accessible surface. The residues that are colored white (19, 64 to 67, 85, 107 to 111, and 114) have no discernible peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum, and residues colored yellow display significantly reduced signal intensity. Residues of the catalytic triad (H21, D39, and C110) are colored red. The protein surface colored green (residue A9) represents the position where the wireframe is attached. Note that the protein surface occluding the substrate is formed by the close proximity of two distal regions of the protein (the dityrosine flap and P107 to G111). (B) Stereo wireframe representation of the active site, in which the VP1-2Apro substrate sequence (residues LITTG, corresponding to P4 to P1′) is colored green and the residues of the catalytic triad are labeled (H21, D39, and C110). Residues S87 to Y89 are part of the dityrosine flap, residues E106 to G111 are part of the active site loop, and residues C65 to S67 are part of the adjacent hairpin loop. Panels A and B are oriented as in Fig. 3 and were prepared using PYMOL (16) and MOLSCRIPT (29)/Raster3D (36), respectively.

The substantial involvement of the F64 to S67 hairpin loop (located between β-strands aII and bII1 [Fig. 3B]) in the conformational exchange process points to the role that this loop plays in defining the geometry of the oxyanion hole within proteinases. The oxyanion hole is a conserved motif in all chymotrypsin-like proteinases, which serves to stabilize the negative charge present on the P1 carbonyl oxygen atom of the tetrahedral intermediate via two precisely orientated backbone amide groups situated on the active site loop. By comparison with the HRV2 2Apro structure (43), the analogous hydrogen bond network in wild-type CVB4 2Apro (modeled in Fig. 7B) involves hydrogen bonds between the amide hydrogens of C110 and G108 and the carbonyl group of P1-T, the threonine residue involved in the scissile bond. The network also involves hydrogen bonds between the side chain of D109 and the backbone amide hydrogens of residues A66 and S67, which serves to stabilize the oxyanion hole by anchoring the active site loop to the adjacent hairpin loop (Fig. 7B). Additional backbone conformational restriction of the active site loop is provided by two hydrogen bonds between residues D109 and E106 and by an imidazolium-thiolate ion pair involving the general base (H21) in the N domain and the catalytic nucleophile in the C domain (47). As CVB4 2Apro carries a mutation of the catalytic nucleophile (C110A), part of the stabilization of the oxyanion hole is missing for this protein.

The distribution of the ca. 30 amide groups that display a significant reduction in peak intensity in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum (Fig. 7A) resulting from the conformational exchange process spreads well beyond the oxyanion hole. The overwhelming majority participate in intramolecular hydrogen bonds in the C domain β-barrel (17 amide groups), segments of the proteinase involved with binding substrate (9 amide groups), interdomain hydrogen bonds (3 amide groups), and cross-strand hydrogen bonds of the N domain (2 amide groups). A minimum model consistent with the data is one where the occupancy of the active site cleft by the VP1-2Apro substrate region (Fig. 7A) leads to the predominant population of the active conformation (similar to that observed for HRV2 2Apro), while nonoccupancy leads to a breakdown of the oxyanion hole conformation and a more widespread destabilization of the C-terminal β-barrel and its relationship to the N domain.

A related scenario has been observed for another viral chymotrypsin-like proteinase. The N-terminal proteinase from the hepatitis C virus NS3 protein (NS3 proteinase) requires the NS4A cofactor for efficient proteolytic processing of the viral polyprotein. In the absence of NS4A, the N-terminal β-barrel displays both substantial millisecond and subnanosecond timescale mobility and is generally less well defined than the C-terminal β-barrel (4). The binding of an inhibitor (and by implication the substrate) is required for the stabilization and full positioning of its catalytic machinery (5). Upon the formation of a complex between NS3 proteinase and the proteinase-binding segment of its cofactor NS4A (in a single-chain construct in the absence of substrate), stabilization of the architecture of the catalytic triad is observed. However, conformational changes throughout large regions of the N domain are also apparent, resulting from positional exchange of the NS4A region between being bound to the NS3 proteinase and being released into solution (35). These dynamics are a consequence of substantial conformational plasticity within the N-terminal domain of NS3 proteinase. However, while the NS3/NS4A system and CVB4 2Apro display substantial dynamic behavior (albeit in different domains), this is not a feature of chymotrypsin-like proteinases in general; for example, the subtilase family member PB92 has a predominantly rigid structure, with the exception of high-frequency dynamics within some surface loops and within a small number of residues closely involved in substrate binding in the active site cleft (34).

An alternative (or supplementary) explanation of the widespread distribution of the intensity reductions in CVB4 2Apro (Fig. 7A) is that the VP1-2Apro substrate region exchanges between two sites, in both of which it is bound to the proteinase. One conformer would involve the VP1-2Apro substrate region being bound in the active site cleft, while the second conformer would have the VP1-2Apro substrate region bound to the surface of 2Apro away from the active site. Binding at the second site would thus make a substantial contribution to the distribution of resonance intensity reduction. This behavior would mirror the repositioning of the N terminus of HRV2 2Apro following cleavage from its VP1 protein (43). In this scenario, the CVB4 VP1-2Apro substrate region would not be positioned exactly as that of the N terminus of HRV2 2Apro in the crystal, since the NMR signals in the corresponding region of the CVB4 2Apro are relatively unaffected by the exchange process. However, such a variation between the two proteins in the interaction surface is likely, given the sequence diversity between HRV2 2Apro and CVB4 2Apro (Fig. 4).

Functional significance of conformational exchange dynamics.

Generally, 2Apro family members are relatively inefficient enzymes; the Km values are approximately 10−4 M, while kcat rate constants are approximately 1 s−1 (32, 51). Hence, whether the low Km values are associated solely with weak binding or are affected by competing proteinase surface binding sites for the substrate, a conformational exchange rate in the range of 100 s−1 to 1,000 s−1 translates to the VP1-2Apro substrate region making hundreds or thousands of visits to the active site prior to cleavage. This means that the equilibrium constant between the two conformers, rather than the rate constant of conformational exchange, is important for the turnover of VP1-2Apro substrate cleavage. Maintaining this equilibrium in favor of the occupation of the active site cleft therefore assists proteolysis, while maintaining this equilibrium against the occupation of the active site minimizes product inhibition following cleavage of the VP1-2Apro substrate region. Product inhibition is a feature of other chymotrypsin-like proteinases; for example, in the maturation of α-lytic proteinase, the C terminus of the cleaved Pro region remains in the active site and inactivates the enzyme (48). Hence, an equilibrium constant in the region of unity for the exchange of the VP1-2Apro substrate region in and out of the active site (whether to solution or to an alternative surface binding site) represents a good compromise between the demands of VP1-2Apro substrate cleavage and the avoidance of product inhibition.

The surface properties of CVB4 and HRV2 2Apro have mechanistic implications.

We have shown recently (19) that the efficient cleavage of eIF4GI by HRV2 2Apro is mediated by an interaction with eIF4GI via an exosite on the proteinase surface, which lies between residues L17 and D35 of the N domain (Fig. 5). The interruption of this interaction by the introduction of specific mutations was detrimental to the rate of eIF4GI cleavage, and indeed in certain cases eIF4GI cleavage was completely inhibited. The structure of CVB4 2Apro is well defined in this region (between R20 and D39), and comparison of the surface properties (Fig. 5C) with those of the parallel region in HRV2 2Apro (Fig. 5D) shows that this region in CVB4 2Apro is significantly more polar than that in HRV2 2Apro. Specifically, the two residues R20 and E34 in CVB4 2Apro, which are predicted to form a salt bridge, are largely responsible for the polar nature of this region. In contrast, the equivalent interaction in HRV2 2Apro connects residues L17 and V30 and is thus considerably more hydrophobic. The nature of this interaction in turn influences the position of the side chain of Y32 (Y36 in CVB4 2Apro). In HRV2 2Apro, the combined result is an extensive hydrophobic surface, whereas the surface of CVB4 2Apro in this region is much more polar.

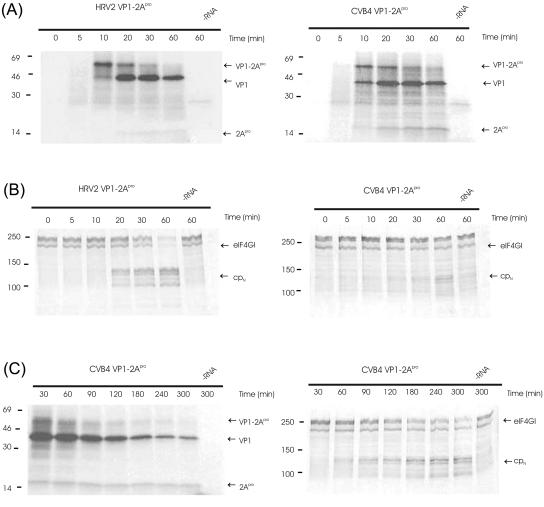

To investigate whether these differences in surface character affect the rates of self-processing or of eIF4GI cleavage, in vitro mRNAs corresponding to the VP1-2Apro proteins of HRV2 and CVB4 were synthesized and translated in RRLs in the presence of [35S]methionine. As previously noted with HRV2 2Apro (21), the initial product of protein synthesis in this system is the VP1-2Apro precursor (Fig. 8A, left panel). Subsequently, this material is processed into the VP1 and 2Apro products. Figure 8A shows clearly that there is no difference between the rates of self-processing of the two 2Apro on their cognate substrates.

FIG. 8.

Kinetics of self-processing and eIF4GI cleavage by HRV2 2Apro and CVB4 2Apro. RRLs were incubated with the indicated mRNAs (∼10 ng/μl). Samples were taken at the designated time points after mRNA addition, and protein synthesis was terminated by addition of unlabeled methionine and cysteine to 2 mM each and Laemmli sample buffer. Aliquots were then analyzed by PAGE; protein standards in kDa are indicated at left of blots. (A) Fluorogram of PAGE (17.5% acrylamide) showing protein synthesis. The positions of the uncleaved precursor VP1-2Apro and the cleavage products VP1 and 2Apro are marked. The fluorogram was exposed for 15 h at −80°C. (B) Immunoblot of PAGE (6% acrylamide), showing the status of eIF4GI. The positions of the uncleaved eIF4GI and the N-terminal cleavage product (cpN) detected by the anti-eIF4GI antiserum are marked. (C) Fluorogram and immunoblot of CVB4 2Apro activity at longer time points. −RNA, without addition of mRNA.

To examine the rates of cleavage of eIF4GI in the RRLs, the proteins from the translation reactions were separated by PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with an antiserum against the N terminus of eIF4GI. As can be seen in Fig. 8B, intact eIF4GI migrates as a series of bands with molecular masses around 220 kDa (17). The bands have different N termini, which arise from the use of different AUG codons during synthesis of eIF4GI (8, 11). Cleavage of eIF4GI by HRV2Apro or CVB4 2Apro at the single recognition site between Arg681Gly (numbering according to reference 11) generates a series of N-terminal cleavage products, which are detected by the N-terminal antiserum used here. The single C-terminal cleavage fragment is not detected by this antiserum. Figures 8B and C show clearly that there is a difference in kinetics of cleavage of eIF4GI by the two 2Apro. The half time of eIF4GI cleavage by HRV2 2Apro was observed to occur between 20 and 30 min, whereas the equivalent point with CVB4 2Apro was reached only after 180 to 240 min.

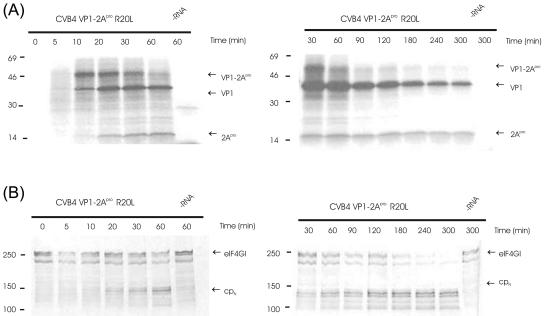

Previously, we have shown that the replacement of L17 in HRV2 2Apro with the corresponding residue from CVB4 2Apro (R20) results in the inability of the HRV2 2Apro enzyme to cleave eIF4GI in RRLs (19), supporting the notion that the surface in this region of HRV2 2Apro constitutes its exosite for binding to eIF4GI. A strong test of this hypothesis would therefore be to improve the cleavage efficiency of CVB4 2Apro on eIF4GI in the RRL system. Accordingly, we replaced R20 in CVB4 2Apro with leucine, the equivalent hydrophobic amino acid from HRV2 2Apro, to create CVB4 2Apro R20L. Self-processing by this mutant protein took place at wild-type levels (Fig. 9A). In contrast, the rate of eIF4GI cleavage was improved significantly, with the half time being reduced to between 60 and 90 min and cleavage being essentially complete after 240 min (Fig. 9B). These results indicate that the mechanisms of recognition of eIF4GI differ between HRV2 2Apro and CVB4 2Apro and that the hydrophobicity of the surface in the region of the exosite for eIF4GI binding has considerable importance for the cleavage efficiency of HRV2 2Apro on eIF4GI in RRLs.

FIG. 9.

Kinetics of self-processing and eIF4GI cleavage by CVB4 2Apro R20L. mRNA (∼10 ng/μl) from CVB4 VP1-2Apro R20L was used to program RRLs. Analysis of self-processing (A) and eIF4GI cleavage (B) were as described in the legend for Fig. 8. Protein standards in kDa are indicated at left of blots. cpN, N-terminal cleavage product; −RNA, without addition of mRNA.

Concluding remarks.

We have determined the solution structure and conformational dynamics of CVB4 2Apro covalently linked through its native sequence to eight C-terminal residues of CVB4 VP1. The surface properties of CVB4 2Apro compared with those of HRV2 2Apro illustrate one way in which the two enzymes differ in mode of recognition of the cellular substrate eIF4GI, while the conformational dynamics illustrate the extent of the regions of the proteinase involved in self-processing. The multifunctional nature of CVB4 2Apro makes it a potential therapeutic target at several stages. Inhibition of intramolecular cleavage would interfere with maturation of the virus, while inhibition of mature 2Apro should both retard translation of the viral polyprotein by interfering with the cleavage of eIF4G proteins and help prevent the pathological consequences of infection that are associated with the cleavage of dystrophin in the heart. The VP1-2Apro substrate region exchange kinetics observed here indicates that neither of these therapeutic strategies should be severely compromised by binding of the VP1 region. In inhibiting intramolecular cleavage, the population of molecules where the active site cleft is occupied by the VP1-2Apro substrate region is similar to the population with the active site cleft unoccupied. Thus, the competition for occupancy of the active site between the VP1-2Apro substrate region and an inhibitor is not significantly in favor of the former. In inhibiting intermolecular cleavage, the relatively low affinity of the VP1-2Apro substrate region for the active site implies very weak binding for the cleaved VP1 product, and the new N terminus of the proteinase may be sequestered by binding away from the active site, as is the case for HRV2 2Apro.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the use of the BBSRC UK National 800 MHz NMR facility at the University of Cambridge and the provision of FELIX 2000 software from Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA. We thank Jeremy Craven for assistance with computing, Paul Thaw for laboratory and spectrometer support, and Cameron McLeod for ICP mass spectrometry measurements.

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation as an Intermediate Research Fellowship awarded to N.J.B., by the BBSRC, and by grants P-16189 and P-17988 from the Austrian Science Foundation to T.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baboonian, C., M. J. Davies, J. C. Booth, and W. J. McKenna. 1997. Coxsackie B viruses and human heart disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 223:31-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badorff, C., N. Berkely, S. Mehrotra, J. W. Talhouk, R. E. Rhoads, and K. U. Knowlton. 2000. Enteroviral protease 2A directly cleaves dystrophin and is inhibited by a dystrophin-based substrate analogue. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11191-11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badorff, C., G.-H. Lee, B. J. Lamphear, M. E. Martone, K. P. Campbell, R. E. Rhoads, and K. U. Knowlton. 1999. Enteroviral protease 2A cleaves dystrophin: evidence of cytoskeletal disruption in an acquired cardiomyopathy. Nat. Med. 5:320-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbato, G., D. O. Cicero, M. C. Nardi, C. Steinkühler, R. Cortese, R. De Francesco, and R. Bazzo. 1999. The solution structure of the N-terminal proteinase domain of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protein provides new insights into its activation and catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 289:371-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbato, G., D. O. Cicero, F. Cordier, F. Narjes, B. Gerlach, S. Sambucini, S. Grzesiek, V. G. Matassa, R. De Francesco, and R. Bazzo. 2000. Inhibitor binding induces active site stabilization of the HCV NS3 protein serine protease domain. EMBO J. 19:1195-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bax, A., G. M. Clore, and A. M. Gronenborn. 1990. 1H-1H correlation via isotropic mixing of 13C magnetisation: a new 3D approach for assigning 1H and 13C spectra of 13C-enriched proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 88:425-431. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belsham, G. J., and N. Sonenberg. 1996. RNA-protein interactions in regulation of picornavirus RNA translation. Microbiol. Rev. 60:499-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley, C. A., J. C. Padovan, T. L. Thompson, C. A. Benoit, B. T. Chait, and R. E. Rhoads. 2002. Mass spectrometric analysis of the N terminus of translational initiation factor eIF4G-1 reveals novel isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 277:12559-12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunger, A. T. 1992. X-PLOR version 3.1: a system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

- 10.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. Delano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J.-S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54:905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrd, M. P., M. Zamora, and R. E. Lloyd. 2002. Generation of multiple isoforms of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI by use of alternate translation initiation codons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4499-4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanagh, J., W. J. Fairbrother, A. G. Palmer, and N. J. Skelton. 1995. Protein NMR spectroscopy: principles and practice. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 13.Chen, J., and K. R. Chien. 1999. Complexity in simplicity: monogenic disorders and complex cardiomyopathies. J. Clin. Investig. 103:1483-1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clubb, R. T., V. Thanabal, and G. Wagner. 1992. A constant-time 3D pulse scheme to correlate intraresidue 1HN, 15N and 13C chemical shifts in 15N-13C labeled proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 97:213-217. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornilescu, G., F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13:289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeLano, W. L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, Calif. [Online.] http://www.pymol.org.

- 17.Etchison, D., S. C. Milburn, I. Edery, N. Sonenberg, and J. W. B. Hershey. 1982. Inhibition of HeLa cell protein synthesis following poliovirus infection correlates with the proteolysis of a 220 kDa polypeptide associated with eukaryotic initiation factor 3 and a cap binding protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 257:14806-14810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrin, T. E., C. C. Huang, L. E. Jarvis, and R. Langridge. 1988. The MIDAS display system. J. Mol. Graph. 6:13-27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foeger, N., E. M. Schmid, and T. Skern. 2003. Human rhinovirus 2 2Apro recognition of eukaryotic initiation factor 4GI. Involvement of an exosite. J. Biol. Chem. 278:33200-33207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser, W, and T. Skern. 2000. Extremely efficient cleavage of eIF4G by picornaviral proteinases L and 2A in vitro. FEBS Lett. 480:151-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaser, W., A. Triendl, and T. Skern. 2003. The processing of eIF4GI by human rhinovirus 2 2Apro: relationship to self-cleavage and role of zinc. J. Virol. 77:5021-5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gradi, A., Y. V. Svitkin, H. Imataka, and N. Sonenberg. 1998. Proteolysis of human eukaryotic initiation translation factor eIF4GII, but not eIF4GI, coincides with the shutoff of host protein synthesis after poliovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11089-11094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grzesiek, S., and A. Bax. 1992. Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31 kDa protein. J. Magn. Reson. 96:432-440. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grzesiek, S., and A. Bax. 1993. Amino acid type determination in the sequential assignment procedure of 13C/15N-enriched proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 3:185-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hentze, M. W. 1997. eIF4G—a multipurpose ribosome adaptor. Science 275:500-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerekatte, V., B. D. Keiper, C. Badorff, A. Cai, K. U. Knowlton, and R. E. Rhoads. 1999. Cleavage of poly(A)-binding protein by coxsackievirus 2A protease in vitro and in vivo: another mechanism for host protein synthesis shutoff? J. Virol. 73:709-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenig, M., A. P. Monaco, and L. M. Kunkel. 1988. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell 53:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kördel, J., N. J. Skelton, M. Akke, A. G. Palmer, and W. J. Chazin. 1992. Backbone dynamics of calcium-loaded calbindin D9k studied by two-dimensional proton-detected 15N NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 31:4856-4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamphear, B. J., R. Kirchweger, T. Skern, and R. E. Rhoads. 1995. Mapping of functional domains in eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) with picornaviral proteases. Implications for cap-dependent and cap-independent translational initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21975-21983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski, R. A., J. A. C. Rullmann, M. W. MacArthur, R. Kaptein, and J. M. Thornton. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liebig, H.-D., E. Ziegler, R. Yan, K. Hartmuth, H. Klump, H. Kowalski, D. Blaas, W. Sommergruber, L. Frasel, B. Lamphear, R. Rhoads, E. Kuechler, and T. Skern. 1993. Purification of two picornaviral 2A proteinases: interaction with eIF-4γ and influence on in vitro translation. Biochemistry 32:7581-7588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malhotra, S. B., K. A. Hart, H. J. Klamut, N. S. Thomas, S. E. Bodrug, A. Burghes, M. Bobrow, P. S. Harper, M. W. Thompson, et al. 1988. Frame-shift deletions in patients with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Science 242:755-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin, J. R., F. A. Mulder, Y. Karimi-Nejad, J. van der Zwan, M. Mariani, D. Schipper, and R. Boelens. 1997. The solution structure of serine protease PB92 from Bacillus alcalophilus presents a rigid fold with a flexible substrate-binding site. Structure 5:521-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCoy, M. A., M. M. Senior, J. J. Gesell, L. Ramanathan, and D. F. Wyss. 2001. Solution structure and dynamics of the single-chain hepatitis C virus NS3 protease NS4A cofactor complex. J. Mol. Biol. 305:1099-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merrit, E. A., and D. J. Bacon. 1997. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277:505-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neri, D., Y. Szyperski, G. Otting, H. Senn, and K. Wüthrich. 1989. Stereospecific NMR assignments of the methyl groups of valine and leucine in the DNA-binding domain of the 434 repressor by biosynthetically directed fractional 13C labeling. Biochemistry 28:7510-7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicholls, A., K. A. Sharp, and B. Honig. 1991. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 11:281-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nigro, G., L. I. Comi, L. Politano, and R. J. Bain. 1990. The incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int. J. Cardiol. 26:271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omichinski, J. G., G. M. Clore, E. Appella, K. Sakaguchi, and A. M. Gronenborn. 1990. High-resolution three-dimensional structure of a single zinc finger from a human enhancer binding protein in solution. Biochemistry 29:9324-9334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pascal, S. M., D. R. Muhandiram, T. Yamazaki, J. D. Forman-Kay, and L. E. Kay. 1994. Simultaneous acquisition of 15N- and 13C-edited NOE spectra of proteins dissolved in H2O. J. Magn. Reson. B 103:197-201. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pestova, T. V., V. G. Kolupaeva, I. B. Lomakin, E. V. Pilipenko, I. N. Shatsky, V. I. Agol, and C. U. T. Hellen. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7029-7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersen, J. F. W., M. M. Cherney, H.-D. Liebig, T. Skern, E. Kuechler, and M. N. G. James. 1999. The structure of the 2A proteinase from a common cold virus: a proteinase responsible for the shut-off of host-cell protein synthesis. EMBO J. 18:5463-5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Read, R. J., M. Fujinaga, A. R. Sielecki, and M. N. G. James. 1983. Structure of the complex of Streptomyces griseus protease B and the third domain of the turkey ovomucoid inhibitor at 1.8 Å resolution. Biochemistry 22:4420-4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed, M. A. C., A. M. Hounslow, K. H. Sze, I. G. Barsukov, L. L. P. Hosszu, A. R. Clarke, C. J. Craven, and J. P. Waltho. 2003. Effects of domain dissection on the folding and stability of the 43 kDa protein PGK probed by NMR. J. Mol. Biol. 330:1189-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sachs, A. B., P. Sarnow, and M. W. Hentz. 1997. Starting at the beginning, middle and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell 89:831-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarkany, Z., T. Skern, and L. Polgar. 2000. Characterization of the active site thiol group of rhinovirus 2A proteinase. FEBS Lett. 481:289-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sauter, N. K., T. Mau, S. D. Rader, and D. A. Agard. 1998. Structure of α-lytic protease complexed with its pro region. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:945-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skern, T., B. Hampoelz, E. Bergmann, A. Guarné, J. Petersen, I. Fita, and M. N. G. James. 2002. Structure and function of picornaviral proteinases, p. 199-212. In B. Semler and E. Wimmer (ed.), Molecular biology of picornaviruses. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 50.Sole, M. J., and P. Liu. 1993. Viral myocarditis: a paradigm for understanding the pathogenesis and treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 22:99A-105A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sommergruber, W., H. Ahorn, A. Zoephel, I. Maurer-Fogy, F. Fessl, G. Schnorrenberg, H.-D. Liebig, D. Blaas, E. Kuechler, and T. Skern. 1992. Cleavage specificity on synthetic peptide substrates of human rhinovirus 2 proteinase 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22639-22644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sommergruber, W., H. Ahorn, H. Klump, J. Seipelt, A. Zoephel, F. Fessl, E. Krystek, D. Blaas, E. Kuechler, H.-D. Liebig, and T. Skern. 1994. 2A proteinases of Coxsackie- and Rhinovirus cleave peptides derived from eIF-4γ via a common recognition motif. Virology 198:741-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sommergruber, W., C. Casari, F. Fessl, J. Seipelt, and T. Skern. 1994. The 2A proteinase of human rhinovirus is a zinc containing enzyme. Virology 204:815-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Straub, V., and K. P. Campbell. 1997. Muscular dystrophies and the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 10:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Towbin, J. A., J. F. Hejtmancik, P. Brink, B. Gelb, X. M. Zhu, J. S. Chamberlain, E. R. McCabe, and M. Swift. 1993. X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy. Molecular genetic evidence of linkage to the Duchenne muscular dystrophy dystrophin gene at the Xp21 locus. Circulation 87:1854-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toyoda, H., M. J. H. Nicklin, M. G. Murray, C. W. Anderson, J. J. Dunn, F. W. Studier, and E. Wimmer. 1986. A second virus-encoded proteinase involved in proteolytic processing of poliovirus polyprotein. Cell 45:761-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voss, T., R. Meyer, and W. Sommergruber. 1995. Spectroscopic characterisation of rhinoviral 2A: Zn is essential for the structural integrity. Protein Sci. 4:2526-2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vuister, G. W., and A. Bax. 1992. Resolution enhancement and spectral editing of uniformly enriched 13C protein by homonuclear broadband decoupling. J. Magn. Reson. 98:428-435. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitehead, B., M. Tessari, P. Dux, R. Boelens, R. Kaptein, and G. W. Vuister. 1997. A 15N-filtered 2D 1H TOCSY experiment for assignment of aromatic ring resonances and selective identification of tyrosine ring resonances in proteins: description and application to photoactive yellow protein. J. Biomol. NMR 9:313-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wittekind, M., and L. Mueller. 1993. HNCACB, a high-sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha- and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101:201-205. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiong, D., G.-H. Lee, C. Badorff, A. Dorner, S. Lee, P. Wolf, and K. U. Knowlton. 2002. Dystrophin deficiency markedly increases enterovirus-induced cardiomyopathy: a genetic predisposition to viral heart disease. Nat. Med. 8:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]