Abstract

All-trans-retinoic acid receptors (RAR) and 9-cis-retinoic acid receptors (RXR) are nuclear receptors known to cooperatively activate transcription from retinoid-regulated promoters. By comparing the transactivating properties of RAR and RXR in P19 cells using either plasmid or chromosomal reporter genes containing the mRARβ2 gene promoter, we found contrasting patterns of transcriptional regulation in each setting. Cooperativity between RXR and RAR occurred at all times with transiently introduced promoters, but was restricted to a very early stage (<3 h) for chromosomal promoters. This time-dependent loss of cooperativity was specific for chromosomal templates containing two copies of a retinoid-responsive element (RARE) and was not influenced by the spacing between the two RAREs. This loss of cooperativity suggested a delayed acquisition of RAR full transcriptional competence because (i) cooperativity was maintained at RAR ligand subsaturating concentrations, (ii) overexpression of SRC-1 led to loss of cooperativity and even to strong repression of chromosomal templates activity, and (iii) loss of cooperativity was observed when additional cis-acting response elements were activated. Surprisingly, histone deacetylase inhibitors counteracted this loss of cooperativity by repressing partially RAR-mediated activation of chromosomal promoters. Loss of cooperativity was not correlated to local histone hyperacetylation or to alteration of constitutive RNA polymerase II (RNAP) loading at the promoter region. Unexpectedly, RNAP binding to transcribed regions was correlated to the RAR activation state as well as to acetylation levels of histones H3 and H4, suggesting that RAR acts at the mRARβ promoter by triggering the switch from an RNA elongation-incompetent RNAP form towards an RNA elongation-competent RNAP.

Retinoids exert their pleiotropic effects on various cellular processes, including growth differentiation and apoptosis. Their effects are mediated mostly through to two types of retinoid receptors, retinoid X receptors (RXR) and retinoic acid (RA) receptors (RAR) (12, 47), which form heterodimers in a ligand-dependent manner (21) and bind to RA-responsive elements (RAREs) to regulate target gene expression (56, 57). Cooperative roles played by RAR and RXR in controlling proliferation and apoptosis have been noted in a variety of cell lines, including embryonal carcinoma cell lines, supporting the view that the RAR/RXR heterodimer is the functional unit in transducing the retinoic acid signal in vivo (3, 17, 19, 32). However, the liganded RXR is transcriptionally inactive unless its partner RAR is itself liganded. The lack of activation by RXR alone has been attributed to an allosteric inhibition of unliganded RAR by RXR (63).

Ligand-mediated activation of RAR is dependent on a carboxy-terminal α-helical region (activating function-2 AD) located in the ligand-binding domain (LBD). Crystal structures of several unliganded and agonist-bound LBDs have shown that upon ligand binding, the activating function-2 AD is folded against the LBD, creating a new interface suitable for coactivator binding (49). Biochemical and expression cloning approaches have led to the identification of several families of coactivators. These include proteins from the basal transcriptional machinery and several transcriptional intermediary factors (29). In addition, ligand binding leads to the release of nuclear receptor corepressors SMRT/TRAC and NCoR/RIP13 (33, 52, 54). Many of these proteins appear to function as components of large, multiprotein complexes with several enzymatic activities (acetylases and kinases).

Despite these advances, how transcription from retinoid-responsive promoters is regulated in the chromatinized state in vivo has remained incompletely understood. We have been interested in the transcription of the RARβ gene because it plays a critical role in mediating ligand-dependent growth inhibition and apoptosis in many cell lines. Moreover, its transcriptional state is thought to be relevant to certain cancers in which RARβ likely exerts antiproliferative effects (10, 26, 31, 35, 43, 44, 53, 64).

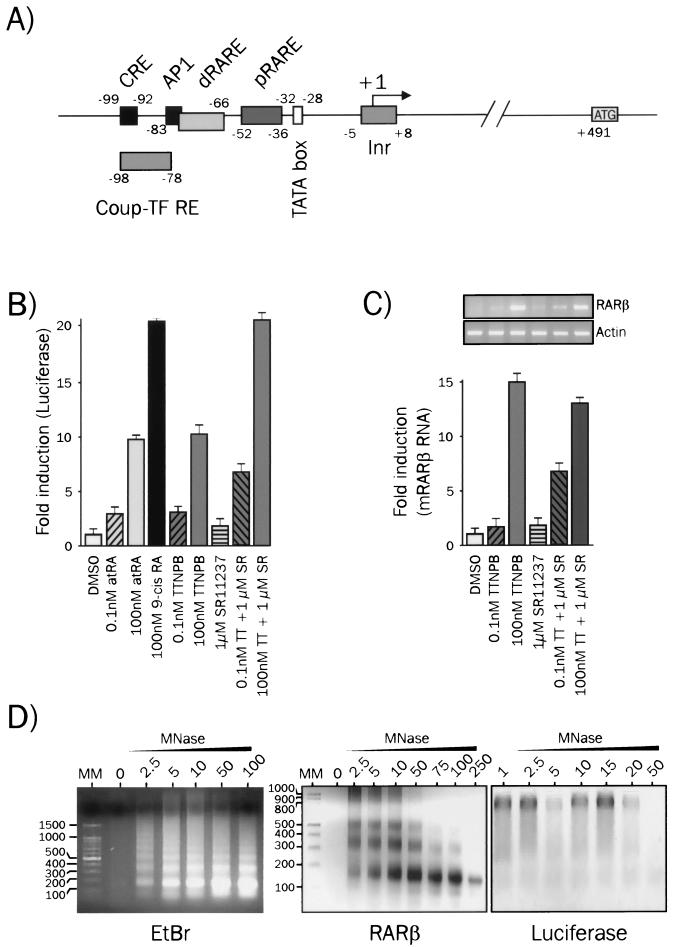

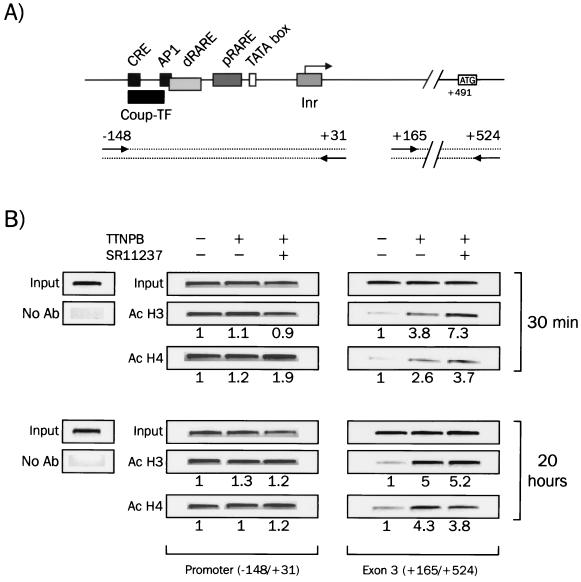

In P19 embryonal carcinoma (EC) cells, the RARβ gene is one of the immediate-early genes induced by all-trans-retinoic acid (atRA) (22). This gene is under the control of a promoter that contains a canonical (proximal) RARE composed of a DR-5 element. It also contains a cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element and an auxiliary (distal) RARE (58, 62) (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

RAR and RXR ligands induce different promoter activities from the transiently expressed or endogenous mRARβ promoter. (A) Diagram of the mRARβ promoter. The nature and the position of functional cis-acting sequences are indicated. CRE, cAMP response element; AP1, activating protein 1; dRARE, distal RARE; pRARE, proximal RARE; COUP-TF, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor. (B) Analysis of mRARβ promoter activity from transiently transfected templates. P19 cells were transiently transfected with the mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene and treated with the indicated ligands for 20 h. Results are expressed as the mean (± standard error of the mean [SEM]) of at least three experiments carried out with triplicate determinations of luciferase activity. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; TT, TTNPB; SR, SR11237. (C) mRNA expression of the endogenous RARβ2 gene. P19 cells were treated with the indicated ligand for 20 h, and the RARβ mRNA level was assayed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Products were analyzed by standard agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by densitometry using Kodak 1D software. (D) Nucleosome assembly on transiently or stably introduced templates. Nucleosomal arrays were detected by limited micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion of chromatin. Nuclei from P19 cells transiently transfected with the mRARβ promoter-luciferase construct were digested with increasing amounts of micrococcal nuclease. Purified DNA was analyzed by Southern blotting using either an RARβ probe or a luciferase probe as described in Materials and Methods. EtBr, ethidium bromide. Lanes MM, size markers (in base pairs).

Previous studies indicated that RARβ promoter activation is regulated by chromatin. First, in contrast to in vitro observations, promoter occupancy in vivo is dependent on stimulation by ligand, which correlates with increased nuclease sensitivity (7, 23). In keeping with this, acetylation or removal of histone tails increases RAR/RXR affinity for a RARE assembled into a nucleosome in vitro (42). The recent findings that unliganded receptors are bound to corepressor/histone deacetylase complexes and that, upon ligand addition, several histone acetylases are recruited to the receptor support the idea that transcriptional activation by RAR/RXR heterodimers coincides with an alteration of chromatin structure (2, 8, 13, 30, 34, 36, 37, 51, 61). Besides RA-dependent promoters, acetylation of local histones has been reported to be concomitant to increased transcription in other hormone-sensitive promoters (14).

Comparison of transcription patterns between transiently and stably transfected reporters is a useful means to unravel molecular mechanisms of nuclear receptor (NR)-controlled transcription (59). Previous structural studies have indicated that, while stably integrated replicating promoters are fully organized into a nucleosomal array, transiently transfected promoters are not fully chromatinized (5, 50). Functional comparisons between transient and stable reporters demonstrated that transcriptional activation patterns differ greatly in the two systems. For example, a transiently transfected human immunodeficiency virus promoter is readily activated by Tat, but the stably integrated promoter has additional requirements for activation (11).

For the more extensively studied mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter, transiently transfected promoters are constitutively transcribed, while in the stable, replicating templates, transcription is seen only after ligand addition (50, 60). In addition, while the progesterone receptor efficiently stimulates transient promoters, it poorly stimulates stably integrated reporters (60). Also notable is the marked difference in the kinetics of MMTV transcription by glucocorticoid: in a replicating template, ligand-activated transcription is followed by a sharp attenuation of transcription in the presence of ligand, while in a transient promoter, transcription continues throughout (4, 39). Some of these differences may be accounted for by the activity of chromatin-remodeling machines (27) and posttranslational modifications of histone H1 (40). Moreover, sensitivity to histone deacetylase inhibitors has been shown to differ markedly in some transient and stable promoters, including the MMTV promoter (6, 9, 18, 45).

Here, we studied RA-activated transcription from two types of RA-responsive promoters, the naturally occurring RARβ and a synthetic promoter, that were introduced either transiently or stably into P19 cells. Transiently introduced reporters supported continuous, cooperative activation of transcription by RAR (retinoid) and RXR (rexinoid) ligands. In contrast, stable reporters displayed a complex biphasic pattern of transcription in which the initial cooperative activation by retinoids and rexinoids was followed by a rexinoid-insensitive state, which could be translated into RXR-mediated repression under certain circumstances. Furthermore, loss of cooperativity was completely relieved upon treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors with a time course similar to that of the onset of loss of cooperativity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Trichostatin A (TSA) was obtained from Wako Biochemicals (Osaka, Japan) and dissolved in ethanol. Sodium butyrate was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), as were atRA and 9-cis-RA. The RAR-specific ligand (E)-4-[2-(5,7,8-tetrahydro-5,5,8,8-tetramethyl-2-naphthyl)-propen-1-yl]benzoic acid (TTNPB) and the RXR-specific ligand SR11237 were synthesized at Hoffmann-La Roche and kindly provided by A. Levin.

Plasmids.

The reporter plasmid carrying the mRARβ promoter-luciferase/GL2 and the deletion mutants characterized in Fig. 7 have been described elsewhere, as well as (DR5)2 Ld40 and DR5 Ld40 (8, 23, 48) pBKCMV SRC-1 was obtained from B. W. O'Malley.

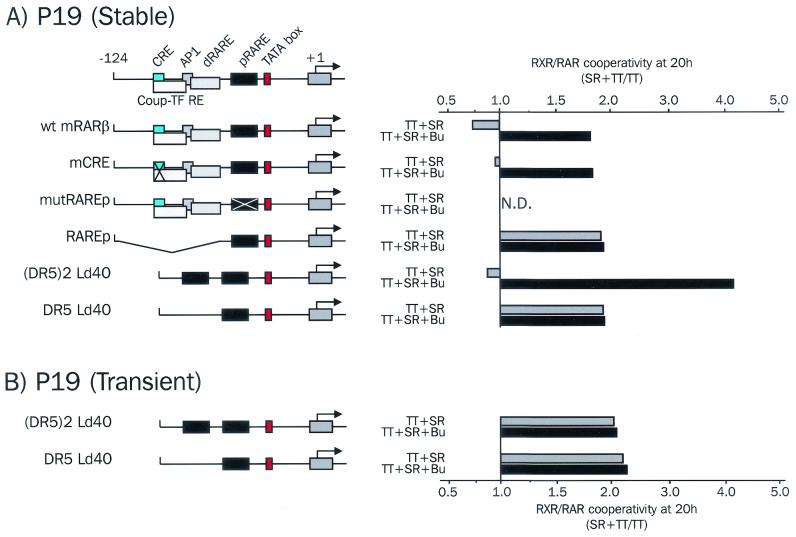

FIG. 7.

Duplicated chromosomal RAREs are required to mediate loss of cooperativity. (A) Loss of cooperativity occurs through two chromosomal RAREs, irrespective of their spacing and sequences. P19 cells were stably transfected with the different mutated or deleted mRARβ promoter constructs and treated with 100 nM TTNPB (TT) alone or with 1 μM SR11237 (SR), with or without 5 mM sodium butyrate (Bu) for 20 h. Results were expressed as the ratio of the luciferase activity measured with RAR and RXR ligands to that in the presence of RAR ligand alone. N.D., not detectable. (B) Transiently introduced reporter genes are not subject to loss of cooperativity. The activity of the (DR5)2 Ld40 and DR5 Ld40 reporter genes was assayed in transient-transfection assays as described above.

Cell culture and transfection.

P2 and P19 EC cells were grown in α minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum plus 1,000 U of penicillin and 10 μg of streptomycin per ml. Transient transfections were performed using the Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Gibco-BRL). Luciferase assays were performed with the dual luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

To obtain stably transfected clones, P19 cells were transfected as follows. The mRARβ2 +124/+14 Luc plasmid (23) and mutant constructs were cotransfected with the pSV2neo plasmid in a 1:10 ratio and selected with G418 (200 μg/ml) for 10 to 15 days. Overexpression of SRC-1 in P19 cells was achieved by selecting cellular clones obtained as follows. P19 cells were transfected as described above using a 1:1 ratio of pBKCMV SRC-1 and mRARβ promoter-luciferase DNAs. From 200 to 500 colonies of G418-resistant cells were pooled and used for analysis. Luciferase activity was normalized against protein concentration.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR.

P19 EC cells were grown as above and treated with the indicated retinoic acid receptor ligands for 20 h. Total RNA was prepared using RNAble reagent (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA (50 μg) was then treated with 10 U of RNase-free DNase I (Genhunter, Nashville, Tenn.) for 1 h at 37°C to digest genomic DNA. The purified RNA was adjusted to 1 μg/μl and checked for integrity by standard agarose gel electrophoresis.

Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using oligo(dT) primers as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega, Charbonnières, France). After 1 h at 37°C, PCRs were carried out as follows: 94°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. Numbers of cycles were adjusted for each gene to ensure that amplification reactions were in a linear range. Primers were designed to amplify cDNAs fragments ranging in size from 300 to 600 bp and were as follows: actin primers, 5"-ATCATGTTTGAGACCTTCAA-3" and 5"-CATCTCTTGCTCGAAGTCCA-3"; RARβ primers, 5"-AAGTGGTAGGAAGTGAGCTG-3" and 5"-CTACATTGAGCAGTATGCCG-3".

Real-time PCR.

After purification of RNAs and reverse transcription as described above, the synthesized cDNAs were analyzed by PCR amplification using the TaqMan PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and the appropriate mix of primers. Typically, a mix of 18S and luciferase primers or mRARβ promoter primers was used. The 18S primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The fluorescein (FAM)/6-carboxymethylrhodamine (TAMRA) probe and forward and reverse primers for the luciferase transcript were ACACCCCAACATCTTCGACGCAGG, GAATTGGAATCCATCTTGCTCC (Luc 1357F), and GGAAGTTCACCGGCGTCA (Luc 1442B), respectively. The FAM/TAMRA probe and forward and reverse primers for the mRARβ transcript were CAGCACCGGCATACTGCTCAA, TCAGTGGATTCACCCAGGC (RAR468F), and TCGGGACGAGCTCCTCAG (RAR557B), respectively. Reactions (40 cycles) and data analysis were carried out with an ABI Prism 7700 (Perkin-Elmer).

Nuclear extracts and Western blotting.

Nuclear extracts from P19 EC and P19 cells stably transfected with SRC-1 were prepared according to Dignam and al. (24). Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunodetection was performed using an anti-SRC-1 antiserum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) as described previously (41).

Micrococcal nuclease digestion.

P19 cells were collected in ice-cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 volumes of buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.15 mM spermine, 0.5 mM spermidine, 5 mM sodium butyrate, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma; dilution, 1:100]). Cells were lysed by several strokes in a Dounce homogenizer with pestle A, and the homogenate was layered onto a 0.8 M sucrose cushion in buffer A. Nuclei (ca. 3 to 5 optical density units at 260 nm) were digested with increasing amounts of micrococcal nuclease (Worthington Biochemicals Corp., Lakewood, N.J.) in a final volume of 300 μl. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of stop buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% SDS, 25 mM EDTA, and 5 mg of proteinase K [Promega] per ml) and incubated for 8 h at 37°C. DNA was then purified, and 50 to 80 mg was digested with 25 U of PstI (RAR) or NotI and EcoNI (luciferase).

Cleaved DNAs were analyzed with native 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Gels were transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham), and DNA was UV-cross-linked to the membrane. Hybridization was carried out with a 614-bp RAR 32P-labeled probe (Rediprime IIp; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), which was amplified from mouse genomic DNA (SmaI-PstI). or with a 559-bp NcoI/EcoNI fragment from pGL3 (luciferase gene). After hybridization, blots were washed and radioactive material was detected using a Storm 860 fluorophosphorimager.

ChIP assays.

For the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, 2 × 106 cells were grown in a 20-cm dish and treated with retinoids and/or TSA as indicated. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde (1% final concentration) at 37°C for 15 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding glycine at 200 mM final concentration. Cells then were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed by adding 400 μl of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1× protease inhibitors [Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.]) to the cellular pellet. DNA was sheared by sonication, and cell debris was eliminated by centrifugation for 15 min. Supernatants were collected and diluted 10-fold in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, protease inhibitors) followed by immunoclearing with 100 μl of a 50% protein A-Sepharose slurry (equilibrated in IP buffer with 200 μg of salmon sperm and 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml) for 2 h at 4°C.

Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight with specific antibodies (anti-acetylated histones were from Upstate Biotech, Inc., Lake Placid, N.Y., and the anti-RNAP antibody C-21 was from Santa Cruz). Complexes were collected by incubation with 60 μl of 50% protein A-Sepharose for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed sequentially for 10 min each in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl), buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl), buffer C (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8]), and twice in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA). Immunocomplexes were eluted off the beads by incubation with 200 μl of 1% SDS-0.1 M NaHCO3 and heated at 65°C for at least 6 h to reverse formaldehyde cross-linking.

DNA was purified with a QIAquick Spin kit (Qiagen). The −124/+31 region was amplified with the following primers: forward 5" RARβ promoter, 5"-GGGAGTTTTTAAGCGCTGTGAG-3", and reverse RARβ promoter, 5"-GGAGCAGCTCACTTCCTACC-3". The +165/+524 region was amplified using 5"-TAGGACCCGCGCGCTCCCGGAG-3" and 5"-ATTGAGCAGTATGCCGGTGCT-3" as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The number of PCR cycles was adjusted to maintain the amplification rate in the linear range (typically between 20 and 30 cycles).

RESULTS

Cooperativity between RXR and RAR is correlated to the absence of detectable nucleosomal repeat pattern in the RARβ promoter.

We noted previously that the RARβ promoter (Fig. 1A) stably integrated into P19 cells adopted a nucleosomal repeat pattern (7). As an initial step of the present work, we investigated whether the mRARβ promoter also displays different functional properties according to its mode of transfection into P19 cells. The activity of a transiently introduced chimeric reporter gene containing the −124/+14 fragment from the mRARβ promoter driving the luciferase gene was monitored by assaying luciferase activity in P19 cell lysates, and that of the endogenous mRARβ promoter was assayed by semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1B and C).

As expected, 9-cis-RA, an RAR-RXR panagonist, stimulated the activity of the transiently introduced reporter more potently than atRA, an RAR-specific ligand (21-fold versus 10-fold) (Fig. 1B). A similar cooperativity was observed when P19 cells were treated for 20 h by RAR subsaturating (0.1 nM) or saturating (100 nM) concentrations of TTNPB, a synthetic retinoid, in combination with 1 μM SR11237, a rexinoid. The overall level of activity was, however, lower when 0.1 nM TTNPB was used, since this ligand concentration promoted an inframaximal luciferase activity.

As shown in Fig. 1C, the endogenous mRARβ promoter responded strongly, much like the transiently expressed reporter gene, to 100 nM TTNPB but not detectably to 0.1 nM TTNPB or 1 μM SR11237. In contrast, the two ligands failed to give cooperative activation of the mRARβ promoter (Fig. 1C), and this lack of cooperativity was also observed for different concentrations of TTNPB and SR11237 (B. Lefebvre and K. Ozato, unpublished observations). Rather, coaddition of the two ligands led to a slight but reproducible decrease (15 to 20%) in endogenous mRARβ promoter activity relative to that by TTNPB alone, indicating different mechanisms of transcription controlling transient and stable promoters.

We then asked whether the mRARβ promoter is organized into nucleosomes when transiently transfected into P19 cells. In the experiment shown in Fig. 1D, nuclei from P19 cells transiently transfected with the RARβ luciferase reporter gene were treated with micrococcal nuclease. Purified DNA was then Southern blotted using a probe corresponding to the RARβ gene or to the luciferase gene (Fig. 1D). The endogenous RARβ promoter gene showed a clear nucleosomal repeat (Fig. 1D), similar to that reported previously with the stably integrated reporter (7). In contrast, the luciferase DNA was digested evenly upon micrococcal nuclease treatment without producing a repeated pattern. These contrasting patterns gave us the impetus to study the correlation between chromatin organization of RA-sensitive genes and cooperativity between RXR and RAR.

Loss of cooperativity between RXR and RAR is also observed in P2 cells.

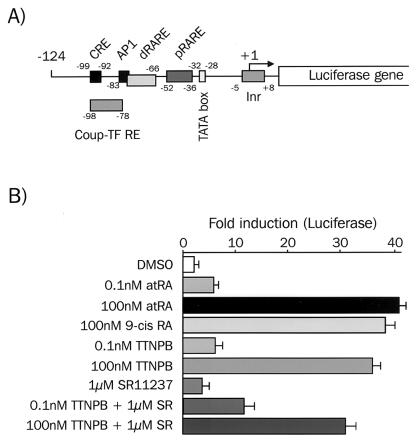

P2 cells are a subclone of P19 cells in which 25 to 30 copies of the chimeric mRARβ promoter-luciferase construct (Fig. 2A) have been introduced. atRA-induced chromatin structure alterations in this cell line recapitulate those observed in P19 cells and paralleled the ability of retinoids and rexinoids to induce transcription (7, 32).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the activity of the stably integrated mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene. (A) Diagram of the mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene. (B) Activity of the mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene in P2 cells. P19 cells stably transfected with the mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene (P2 cells) were treated with the indicated ligands for 20 h. Results were obtained and expressed as described for Fig. 1.

atRA and 9-cis-RA stimulation of P2 cells gave a similar level of integrated reporter activity, reproducing the lack of cooperativity observed for the mRARβ promoter in P19 cells with retinoids and rexinoids (Fig. 2B). Similarly, treatment of P2 cells with 1 μM RXR-specific ligand SR11237 had little effect on luciferase activity (≈2-fold). On the other hand, the RAR-specific ligand TTNPB (100 nM) strongly stimulated the integrated reporter activity. Coaddition of the two ligands at these concentrations failed to give cooperative activation in the stably integrated reporter but again led to a decrease (10 to 15%) in reporter activity relative to that triggered by TTNPB alone. These results indicated that retinoids and rexinoids do not cooperatively activate stably integrated RARβ promoters, in contrast to transiently transfected promoters.

Furthermore, we noted that, similar to the results with P19 cells, RAR and RXR cooperatively stimulated RARβ promoter activity in NIH 3T3 cells for transiently introduced reporters, but not for the same stably introduced reporter (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished), indicating that the different patterns of mRARβ promoter activation are not a property restricted to P19 cells. Finally, this cooperativity was not specific for these two ligands, since other synthetic ligands elicited the same response profile (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished).

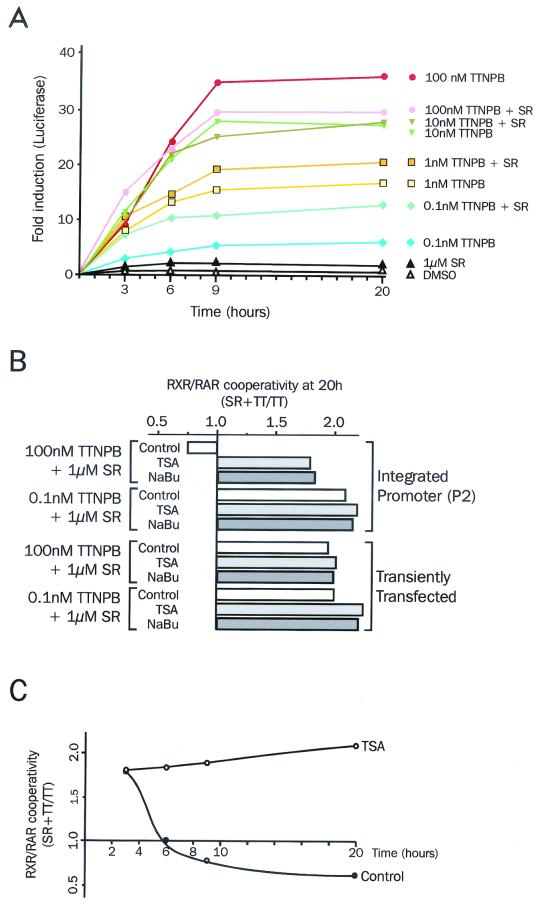

Cooperativity between RAR and RXR is abrogated in stably integrated promoters in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

Since P2 cells faithfully recapitulated events leading to transcriptional activation of the mRARβ promoter, we carried out a combined dose-response and kinetic analysis of the activity of this promoter in P2 cells in response to various concentrations of TTNPB, which displays an affinity for RARα of about 10 to 20 nM. The luciferase activity was assayed in cell extracts after treatment with the indicated combinations of ligands (0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM TTNPB and 1 μM SR11237) for various periods of time (3 h to 20 h) (Fig. 3A).

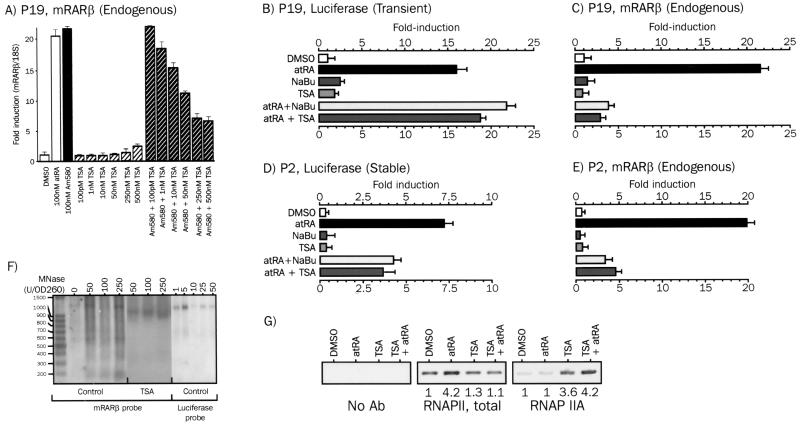

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of loss of cooperativity by histone deacetylase inhibitors. (A) Kinetics of cooperative activation of the mRARβ promoter by RAR and RXR ligands. P2 cells were treated with 100 mM TTNPB alone or with 1 μM SR11237 for the indicated times. Luciferase activity was assayed, and results were expressed as detailed for Fig. 1. (B) Restoration of two-ligand cooperativity by TSA. P19 cells transiently transfected with the mRARβ promoter-Luc reporter or P2 cells were treated with 0.1 nM or 100 nM TTNPB and 1 μM SR11237, with or without 250 nM TSA or 10 mM sodium butyrate (NaBu), for 20 h as indicated. Results were expressed as the ratio of the luciferase activity measured with RAR and RXR ligands to that in the presence of RAR ligand alone. (C) Delayed effect of TSA. P2 cells were treated with 100 nM TTNPB (TT) alone or with 1 μM SR11237 (SR) with or without 250 nM TSA for the indicated times. Results were expressed as in panel B.

Subsaturating concentrations of TTNBP (0.1 nM and 1 nM) (Fig. 3A) induced a moderate luciferase response: it increased twofold in the presence of the rexinoid SR11237, which was ineffective by itself. Increasing the TTNPB concentration to 10 nM boosted the luciferase response, but revealed that the rexinoid became unable to act in concert with TTNPB. A saturating concentration of TTNPB (100 nM) had a different impact on the detected luciferase activity. At an early stage (3 h), coaddition of 100 nM TTNPB and 1 μM SR11237 yielded a cooperative enhancement in promoter activity, in that while TTNPB gave only a 7-fold increase, the two ligands together gave a 15-fold induction in reporter activity. At 6 h, however, the two ligands did not elicit a cooperative response, with a 20- to 25-fold enhancement by TTNPB alone or together with SR11237. Moreover, cooperativity was not detected at either 9 or 20 h after ligand addition. Rather, at these points, coaddition of the two ligands led to a slight but reproducible reduction in promoter activity compared to TTNPB alone. These results indicate that in the integrated RARβ promoter, RAR and RXR ligands stimulate transcription cooperatively only at an early stage characterized by low RAR activity, but that this cooperativity is lost at later stages occurring after prolonged stimulation (>6 h) by retinoids.

To examine whether the status of RAR activation influences RXR/RAR cooperativity, we compared the reporter activity at 100 nM TTNPB to that observed at 0.1 nM TTNPB, a 1,000-fold-lower concentration than the optimal concentration of this ligand, upon coaddition of 1 μM SR11237. Results were expressed as the ratio of the luciferase activity measured with RAR and RXR ligands to that in the presence of RAR ligand alone, thereby reflecting the cooperativity between the two receptors (Fig. 3B). As shown above, a 20-h treatment of P2 cells with RXR and RAR ligands yielded a response inhibited by 15 to 20% compared to that with RAR ligand alone, reflected by a 0.8 cooperativity ratio. In contrast, 0.1 nM TTNPB allowed a cooperative response (factor, 1.8 to 2.0).

As expected, the transiently transfected promoter showed cooperativity when stimulated with 0.1 nM TTNPB and 1 μM SR11237, with a cooperativity ratio of about 2.2 to 2.5. A similar result was observed with 1 nM TTNPB (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished) and 100 nM TTNPB (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the stably integrated promoter can mount cooperative activation by the two ligands only when the level of activation by RAR ligand is low and that cooperativity is lost when the promoter is strongly activated by RAR.

Cooperativity between RAR and RXR is sensitive to histone deacetylase inhibitors.

Since the loss of cooperativity occurred only for the stably integrated or endogenous RARβ promoters and thereby suggested an active role of chromatin in this process, we next tested the effect of TSA and sodium butyrate, two potent histone deacetylase inhibitors, on RAR/RXR cooperativity. Note that control experiments showed that histone deacetylase inhibitors did not modify luciferase mRNA and protein stabilities (P. Lefebvre and C. Brand, unpublished data). At low TTNPB concentrations (0.1 and 1 nM), TSA and sodium butyrate maintained the cooperativity between TTNPB and SR11237, and similar results were found in NIH 3T3 cells (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished). Interestingly, loss of cooperativity was counteracted by sodium butyrate and TSA, restoring a degree of cooperativity similar to that observed at early stages, suggesting an active role of an acetylation-deacetylation phenomenon in this process.

Next, we examined the kinetics of TSA action on this cooperative process (Fig. 3C). In the early stages, TTNPB alone yielded a low reporter activity (Fig. 3A) and TSA treatment did not modify the level of cooperativity (Fig. 3C). Subsequently, TSA treatment maintained the two-ligand cooperativity. Indeed, while treatment of P2 cells with 100 nM TTNPB and 1 μM SR11237 did not lead to cooperative activation after 20 h, TSA again allowed cooperative activation of the promoter in these conditions, as well as sodium butyrate (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished). These results indicated that histone deacetylase inhibitors prevented the loss of cooperativity that begins at a later stage of transcription, although it has no effect on ligand cooperativity that takes place at an early stage. Thus, loss of cooperativity is caused by a late-acting mechanism sensitive to histone deacetylase inhibitors.

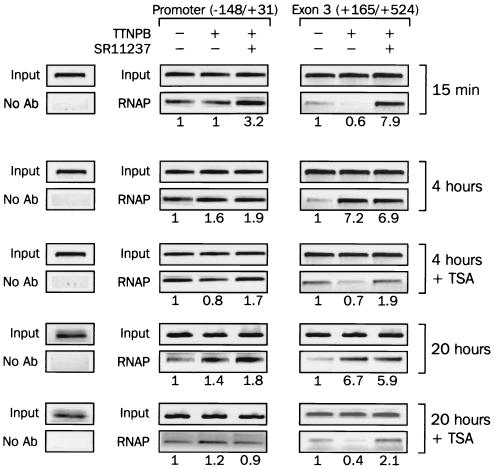

Histone deacetylase-sensitive loss of cooperativity is independent of H3 and H4 acetylation status at the RARβ promoter.

The above results raised the possibility that the observed loss of cooperativity involved an histone acetylation-deacetylation mechanism. To address this possibility further, we next examined the histone acetylation status of the RARβ promoter by using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 4A). Antibodies specific to acetylated histones H3 and H4 were used to immunoprecipitate formaldehyde-cross-linked, sonicated chromatin from P19 cells following the different ligand treatments. Quantitative PCR analysis of DNA input or bound to immunocomplexes were carried out to detect a fragment of 179 bp of the endogenous mRARβ promoter (Fig. 4B). ChIP analysis with antibodies to acetylated H3 and acetylated H4 demonstrated a high constitutive H3 and H4 histone acetylation at the mRARβ promoter in naive cells. Adding TTNPB (100 nM or 1 μM) alone or in the presence of SR11237 (1 μM) caused no significant changes in the histone acetylation status of the promoter after 30 min, and similar results were observed after longer treatment (20 h). Ro41-5353, an RAR antagonist, did not modify the H3 and H4 acetylation level (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished).

FIG.4.

Analysis of H3 and H4 acetylation levels at the mRARβ promoter and RARβ2 gene exon 3 upon different ligand treatments. (A) Diagram of sequences along the RARβ gene immunopurified by ChIP assays. (B) P19 cells were treated with 100 nM TTNPB alone or with 1 μM SR11237 for the indicated periods of time and subjected to cross-linking by 1% formaldehyde treatment. Chromatin fragments were then immunoprecipitated using antibody (Ab) against acetylated (Ac) histone H3 or H4 and analyzed by quantitative PCR for the presence of the mRARβ promoter or exon 3. Input, 1/10 of input DNA was analyzed by PCR to ensure equal loading. Amplified DNAs were quantified by densitometry, and results were expressed relative to the control, which was arbitrarily set to 1. All experiments were carried out in triplicate and S.D. never exceeded 0.25.

As a specific control for these experiments, we performed PCR analyses of a DNA fragment located on exon 3 (corresponding to the first exon of the RARβ2 isoform) of the mRARβ gene (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, ChIP analysis with acetylated H3 or H4 revealed a low level of acetylation in the absence of ligand. Adding TTNPB alone or in the presence of SR11237 led in this case to a strong increase in the level of both H3 and H4 acetylation. These results indicate that loss of cooperativity, although dependent on chromatin and sensitive to histone deacetylase inhibitors, does not involve a local deacetylation of the RARβ promoter but is associated with hyperacetylation of mRARβ regions located downstream of the promoter.

Histone deacetylase inhibition prevents RNAP recruitment to transcribed regions.

To better understand the molecular mechanism underlying the different steps in activation of the RARβ promoter, we examined the engagement of RNA polymerase II (RNAP) using the ChIP assay with an antibody against the N terminus of the RNAP rpb1-encoded subunit, which recognizes this polypeptide irrespective of posttranslational modifications. As shown in Fig. 5, the ChIP assay revealed that a considerable amount of RNAP is constitutively associated with the RARβ promoter in the absence of ligand. Adding 1 μM TTNPB alone for 15 min or longer did not significantly increase RNAP recruitment, showing that RNAP is already engaged on the promoter in basal conditions. Challenging cells with both TTNPB and SR11237 led to an increase in RNAP loading to the promoter only at a very short incubation time (15 min).

FIG. 5.

Recruitment of RNAP to the RARβ promoter upon ligand and histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment. P19 cells were treated with 100 nM TTNPB alone or with 1 μM SR11237 with or without 250 nM TSA for the indicated periods of time. Cells were treated with formaldehyde, and RNAP was immunopurified using antibody (Ab) against total RNAP. Associated sequences from the mRARβ promoter or exon 3 of the RARβ gene were detected by PCR as described for Fig. 4. The amount of amplified DNA was quantified and expressed as in Fig. 4.

We next examined the ability of each ligand to initiate transcriptional elongation by detecting the presence or absence of the exon 3 DNA region in RNAP immunoprecipitates. As shown in Fig. 5B, only a small amount of RNAP was present on this part of the gene in the absence of ligand or upon treatment for 15 min with 1 μM TTNPB. However, coaddition of SR11237 dramatically increased this association (eightfold). After 4 h, TTNPB induced a strong association of RNAP with exon 3 (sevenfold), but no potentiation was observed upon coaddition of SR11237.

We next asked how TSA affected RNAP loading at prolonged incubation times, conditions in which this histone deacetylase inhibitor restores the RXR-RAR cooperativity (see Fig. 3). TSA treatment considerably reduced RNAP association in the presence of TTNPB (10-fold decrease), which was further sensitive to SR11237 and increased by 2-fold. In contrast, RNAP loading to the promoter region was not affected in these conditions. These results indicated that the activation of the RARβ promoter takes place following a two-step process. The first step is characterized by the low ability of TTNPB to promote RNAP engagement on the mRARβ gene, a step during which SR11237 can generate a cooperative activation. The second and later stage, inhibited by histone deacetylase inhibitors, is characterized by the lack of cooperativity between RXR and RAR and by maximal engagement of RNAP on the mRARβ gene.

Histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated inhibition of the mRARβ promoter is an RAR-controlled event.

The inhibition of RNAP loading at the second stage of promoter activation by histone deacetylase inhibitors suggested that RAR is the molecular relay of a histone deacetylase inhibitor-controlled mechanism. We thus investigated whether RAR transcriptional activity could be altered by TSA. The mRARβ promoter activity was monitored by real-time PCR detection of RARβ or luciferase transcripts in P19 or P2 cells. P19 cells were first treated with increasing concentrations of TSA or of TSA and Am580, an RAR-specific ligand exhibiting properties strictly similar to atRA and TTNPB in this system. While TSA only weakly induced the basal transcriptional activity of the mRARβ promoter at high concentrations (250 and 500 nM) and did not affect the response to rexinoids, Am580 promoted a very strong induction of the promoter activity. This RAR-mediated induction was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by TSA, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of about 10 to 50 nM.

The effect of histone deacetylase inhibition on transiently introduced templates and on stably integrated promoter activities (Fig. 6B through E) was monitored by assaying mRNA transcripts originating from each type of promoter. The transiently introduced reporter gene was strongly inducible by atRA (and TTNPB; data not shown), and TSA did not alter its responsiveness to an RAR-specific ligand (atRA) (Fig. 6B). In the same cellular background, we observed that the endogenous mRARβ promoter activity was also highly inducible by atRA (Fig. 6C) as well as in P2 cells (Fig. 6D) but that, in contrast to its transiently transfected counterpart, it was strongly repressed by TSA. Similarly, the activity of the stably integrated chimeric reporter gene was highly sensitive to TSA-mediated inhibition (Fig. 6E).

FIG. 6.

Histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated inhibition of the mRARβ promoter. (A) RAR-controlled activity of the mRARβ promoter is sensitive to TSA. P19 cells were transfected with the mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter and treated with Am580 alone or with TSA as indicated for 6 h. RARβ transcripts were quantified by real-time PCR as described in Materials and Methods, and results are expressed as the mean (± SEM) of three independent assays. (B, C, D, and E) TSA selectively affects the activity of chromosomal templates. (B and C) P19 cells were transiently transfected with the mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene and treated for 6 h with 100 nM atRA, 5 mM sodium butyrate (NaBu), and 250 nM TSA as indicated. Transcripts from the luciferase and RARβ genes were quantified by real-time PCR. (D and E) P2 cells were treated with atRA and histone deacetylase inhibitors as above, and luciferase mRNA (D) and RARβ mRNA (E) were quantified by real-time PCR. (F) TSA alters the nucleosomal array of the RARβ promoter. The nucleosomal organization of the mRARβ promoter was characterized by the micrococcal nuclease (MNase) assay as described for Fig. 1. Nuclei from P19 cells treated or not with 250 nM TSA for 6 h were analyzed as described for Fig. 1.

It is worth noting that inhibition was, in all cases, about 60 to 70% but that a residual activity remained detectable and was not repressed by higher concentrations of TSA or butyrate. Taken together, these results suggest that the RAR transcriptional response to retinoids is only partly sensitive to histone deacetylase inhibitors and furthermore define RAR as a likely target for histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated relief of loss of cooperativity. By promoting hyperacetylation of histone tails, histone deacetylase inhibitors could trigger a general decompaction of chromatin structure.

To assess this possibility, limited micrococcal nuclease digestion of P19 cell nuclei was carried out after or without TSA treatment and compared to the digestion pattern of the transiently introduced mRARβ promoter-luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 6F). Interestingly, no nucleosomal ladder was detected in TSA-treated chromatin, suggesting a general unpacking of the nucleosomal array on the mRARβ promoter.

A second RARE is required for inhibition of RXR-RAR cooperativity.

To gain insight into the molecular basis of loss of cooperativity, we tested a series of mutant RARβ reporters stably integrated into P19 cells (Fig. 7). A mutant reporter with an altered cAMP response element behaved in a manner similar to the wild type, as no cooperativity was observed after 20 h, which was fully restored upon histone deacetylase inhibition (Fig. 6A). A reporter with a mutation in the proximal RARE (DR5) failed to respond to either ligand alone or in cooperativity, underlining the predominant role of this response element in the regulation of mRARβ promoter activity. More informative was a mutant reporter from which both the distal RARE and cAMP response element were deleted. This mutant displayed clear cooperativity in response to concomitant RXR and RAR stimulation. Since this mutant contains only one RARE, it was of importance to ascertain whether another promoter containing only one RARE also sustained cooperative activation in response to both types of ligands.

To this end, a synthetic reporter, (DR5)2 Ld40, consisting of a duplicated RARE connected to a basal promoter (a TATA box and initiator element) (Fig. 7A) with altered spacing compared to the mRARβ promoter (22 versus 14 bp), was stably introduced into P19 cells. Promoter activity was tested following stimulation with RAR and/or RXR ligands. Responses obtained with this promoter paralleled those obtained with the RARβ promoter: coaddition of 100 nM TTNPB and 1 μM SR11237 yielded no cooperative response (Fig. 7A), although cooperativity was restored upon histone deacetylase inhibition and observed at lower concentrations of TTNPB (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished).

The DR5 Ld40 promoter, containing only one consensus DR5 RARE, was then integrated into the P19 cell genome, and its activity was assayed as above. As observed for the RAREp mutant, this construct also displayed a cooperative response in response to RAR and RXR ligands (Fig. 7A). These results show that loss of cooperativity is not a special feature of the RARβ promoter and requires at least two RAREs.

Finally, to ascertain whether loss of cooperativity is conditioned by chromatin assembly on the promoter, the activity of the synthetic reporters (DR5)2 Ld40 and DR5 Ld40 was tested in transient transfections. Again, results with these synthetic promoters paralleled those of the natural RARβ promoter (Fig. 2B), as cotreatment with the two ligands led to a cooperative activation of transcription (Fig. 7B). These data thus indicate that loss of cooperativity occurs only in chromosomal promoters possessing more than one RARE, but not in those harboring a single RARE.

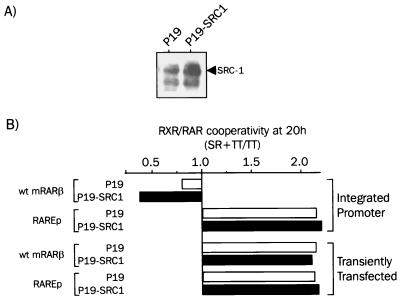

Increased coactivator recruitment and loss of cooperativity.

In contrast to transiently introduced templates, chromosomal templates exhibited decreased activity in conditions thought to favor coactivator recruitment to the promoter. We thus examined the effect of stable overexpression of SRC-1, a member of the p160 coactivator family involved in the retinoid response (37). Western blot analysis confirmed that levels of SRC-1 expression were higher in these cells than in those transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 8A). In transient-cotransfection assays, SRC-1 displayed the expected coactivator activity, since it significantly enhanced retinoid-induced RARβ reporter activity in response to TTNPB alone, as well as in response to TTNPB and SR11237 (Fig. 8B). A similar result was obtained with the RAREp construct, which harbors the proximal RARE as a unique cis-acting element.

FIG. 8.

Effect of overexpression of SRC-1 on transient or stable mRARβ promoter. (A) Expression of SRC-1 in P19 cells stably transfected with SRC-1 or empty vector. A total of 50 μg of proteins from whole-cell extracts of P19 cells and P19 cells stably transfected with an SRC-1 expression vector were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods, using a polyclonal antibody against SRC-1. (B) SRC-1 potentiates transcription from extrachromosomal templates. P19 cells were transiently transfected with the RARβ or RAREp luciferase reporter gene with or without the SRC-1 expression vector and treated with 100 nM TTNPB (TT) alone or with 1 μM SR11237 (SR) for 20 h. Results from luciferase assays are expressed as the mean (± SEM) of three independent experiment with triplicate determination of luciferase activity.

P19-SRC-1 cells, in which the wild-type RARβ reporter gene has been stably integrated, exhibited an unexpected sensitivity to retinoids. RARβ promoter activity in P19-SRC-1 cells was enhanced in response to 0.1 and 100 nM TTNPB (Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished). However, activation of RXR by SR11237 resulted in a significant repression of promoter activity, gauged by a cooperativity factor of 0.8 versus 0.4. Moreover, a cooperative response was not observed even at subsaturating concentrations of TTNPB (0.1 and 1 nM; Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished), which yielded a cooperative response in the absence of SRC-1 (Fig. 3).

As a control for specific effect for multiple responsive elements, we next tested promoter activity with P19 cells stably transfected with the RAREp construct and the SRC-1 expression vector. No change in the cooperativity between RAR and RXR ligands was observed. Thus, increased expression of SRC-1 led to a negative regulation of the RARβ promoter in the presence of an RXR ligand and required a tandem repeat of RARE.

DISCUSSION

Chromatin-specific regulatory mechanism in activation of the mRARβ promoter.

Micrococcal nuclease digestion studies failed to detect a nucleosomal ladder on the transiently transfected RARβ promoter, whereas such a pattern was detectable on the endogenous mRARβ promoter. This is in agreement with a supposed incomplete chromatin organization of transient templates and previous studies showing that transiently transfected plasmids, in opposition to endogenous genes, are not fully chromatinized (5, 16). Retinoids and rexinoids cooperatively activate the mRARβ promoter in P19 and NIH 3T3 cells on these latter templates, but not from single or multiple stably integrated copies in P19 and NIH 3T3 genomes, suggesting the existence of a chromatin-mediated regulation process. Moreover, a synthetic retinoid-responsive reporter with a tandem repeat of the canonical DR5 response element exhibited the same dichotomic sensitivity between transient and stable transfection, supporting the in vivo relevance of loss of cooperativity. Remarkably, stably transfected reporters retaining only a single RARE consistently displayed cooperative activation by RAR and RXR. Thus, loss of cooperativity requires multiple RAREs, irrespective of their sequence and of the relative spacing between the TATA box and the RAREs.

The idea that mRARβ promoter engagement critically affects the extent of loss of cooperativity is supported by two sets of evidence. First, loss of cooperativity is not observed at suboptimal retinoid concentrations, and rexinoids cooperatively enhance transcript accumulation even beyond a 20-h stimulation for chromosomal reporters in these conditions. These results are consistent with previous reports showing a cooperative effect of retinoids and rexinoids on cellular differentiation and apoptosis only at subsaturating retinoid concentrations, emphasizing the biological importance of loss of cooperativity (13, 46, 48). Second, SRC-1 overexpression leads to an RXR-mediated negative regulation of the promoter. We also observed that activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A pathway potentiated retinoid-induced transcription on transiently transfected templates. In contrast, cAMP elicited a stronger repression of mRARβ promoter activity in the presence of both RXR and RAR ligands (cooperativity factor of 0.6 versus 0.8; Lefebvre and Ozato, unpublished). These data support the view that increased NCoA recruitment to the promoter (through either multiple RAREs, overexpression of nuclear coactivator A, or costimulation of several signaling pathways) is likely to be a triggering factor for loss of cooperativity.

Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on RARβ transcriptional activation.

Histone deacetylase inhibitor (TSA and sodium butyrate) effects are observed at the second stage of ligand activation, indicating that their effects are delayed and follow a kinetics similar to that of loss of cooperativity. Although these results suggested a link between histone acetylation and loss of cooperativity, H3 and H4 acetylation levels before and after ligand addition remained unchanged in the promoter vicinity, which is in contrast to results reported for other retinoid-regulated genes (14). However, the lack of histone hyperacetylation during remodeling and promoter activation has recently been shown for several yeast promoters, including PHO8 and HO (20).

The constitutive loading of RNAP on the mRARβ promoter, which is also detected on transiently transfected templates (Lefebvre and Brand, unpublished), was unexpected considering previous studies documenting the absence of factor binding prior to ligand addition (15, 23). However, a lack of in vivo footprinting could reflect different binding stabilities that can be detected more readily by formaldehyde cross-linking. More importantly, a direct correlation between H3 and H4 hyperacetylation, transcriptional activity of the promoter, and RNAP loading was found in a region mapping to exon 3 of the RARβ gene. Thus, RARβ transcriptional activity is correlated to RNAP progression along the gene but not to its favored tethering to the promoter. This view is further substantiated by the correlation between increased progression of RNAP to exon 3 upon simultaneous and cooperative activation of RAR and RXR. Interestingly, RNA elongation on nucleosomal DNA is strongly influenced by histone acetylation, most notably by a decreased pause site residence time (55).

Cooperative activation was restored upon histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated inhibition of RAR activity, with a measured IC50 in agreement with the reported IC50 of histone deacetylase 1, 4, or 6 by TSA in vitro (28, 38). While this observation does not easily fit with our current understanding of NR-mediated transcription, there are some precedents for our observations. The MMTV promoter again provides a very interesting point of comparison, since its glucocorticoid-induced activation is selectively inhibited by histone deacetylase inhibitors (6, 9). Of note is the occurrence of two functional glucocorticoid response elements in this viral promoter, which however responded biphasically to histone deacetylase inhibitors (6). The insensitivity of the endogenous or integrated mRARβ promoters to histone deacetylase inhibitors in the early phase is in some aspects very similar to that of the CREB-regulated somatostatin gene (45). In this model, chromatin-specific regulation of CREB phosphorylation was found to occur at late stages of promoter activation, consistent with the view that the nucleosomal architecture limits access of activating protein kinase A to nucleosomal DNA-bound CREB.

It is still unclear how increasing the acetylation rate of a cellular component would lead to a partially decreased RAR activity, which depends on both template integration into the genome and the number of response elements. RAR could be a direct target for acetylases, but in vitro acetylation assays using purified RAR and RXR failed to reveal significant acetylation of these two NRs, in conditions where H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 are readily modified (Lefebvre and Brand, unpublished). Histone deacetylase inhibitors may also activate the MEK pathway (25), but no significant activation of the MEK/ERK pathway by histone deacetylase inhibitors was detected in P19 cells, and several protein kinase inhibitors, including PD98059, a specific inhibitor of MEK1 and MEK2 (1), were unable to reverse the histone deacetylase inhibitor effect on mRARβ promoter activity (Lefebvre and Brand, unpublished).

Interestingly, acetylation of ACTR, an NR coactivator, negatively regulates its association with the estrogen receptor, providing a link between transcriptional attenuation and acetylation of components of the transcription machinery. However, this inactivation process was evidenced with a transiently transfected reporter gene (14). p300/CBP but not pCAF may acetylate ACTR and TIF2 in vitro, raising the possibility that acetylation or other posttranslational modifications occur as a function of the molecular composition of the cofactor complex. This raises the issue as to the possible role of chromatin assembly on the RARβ promoter in dictating this molecular composition and the ability of RXR-RAR dimer to favor RNA elongation through hyperacetylated chromatin. Indeed, we observed that TSA is able to significantly decrease the quality of the nucleosomal array on the mRARβ promoter, indicating an altered nucleosome accessibility and spacing. Along those lines, transcription from chromosomal MMTV templates is uniquely dependent on the interaction between the glucocorticoid receptor and the chromatin remodeling complex BRG1/BAF (27).

In summary, our work points to three important conclusions. First, we showed that maximal activation of the mRARβ promoter, probably through increased tethering of coenzyme A to the promoter region, converts rexinoids into inactive states or even into being repressors of a chromatinized promoter activity. These results raise the possibility that this histone deacetylase-regulated negative control provides a means of ensuring highly gradual hormonal response and subsequent attenuated transcription. Second, our previous in vitro results showing that histone acetylation is required for RAR/RXR binding to a nucleosomal RARE (42) further suggest that receptors are constitutively bound to DNA in the P19 background. In support of these observations, ChIP experiments performed with anti-RXR or anti-RNAP antibodies showed constitutive binding of these proteins to the promoter in all conditions (P. Lefebvre, data not shown). Thus, histone deacetylase inhibitors are likely to affect a step downstream of transcription factor loading per se, and preliminary data showing that retinoids induce Ser 5 hyperphosphorylation of the RNAP C-terminal domain would implicate C-terminal domain kinases in this process. Third, it also emphasizes the general importance of studying each promoter as an integrated component in which transcriptional activation results from mutual interaction between the different transcription factors and is regulated by the chromatin environment.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Farina, J. Lu, V. Horn, C. Contursi, and C. Rachez for helpful discussions during this work. We thank B. W. O'Malley (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston) for providing us with the SRC-1 expression vector.

Part of this work was financed by grants from INSERM, Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, and Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Comité du Nord-Pas de Calais).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi, D. R., A. Cuenda, P. Cohen, D. T. Dudley, and A. R. Saltiel. 1995. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27489-27494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alland, L., R. Muhle, H. Hou, Jr., J. Potes, L. Chin, N. Schreiber-Agus, and R. A. DePinho. 1997. Role for N-CoR and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 387:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apfel, C. M., M. Kamber, M. Klaus, P. Mohr, S. Keidel, and P. K. Lemotte. 1995. Enhancement of HL-60 differentiation by a new class of retinoids with selective activity on retinoid X receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270:30765-30772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer, T. K., H. L. Lee, M. G. Cordingley, J. S. Mymryk, G. Fragoso, D. S. Berard, and G. L. Hager. 1994. Differential steroid hormone induction of transcription from the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Mol. Endocrinol. 8:568-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archer, T. K., P. Lefebvre, R. G. Wolford, and G. L. Hager. 1992. Transcription factor loading on the MMTV promoter—a bimodal mechanism for promoter activation. Science 255:1573-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartsch, J., M. Truss, J. Bode, and M. Beato. 1996. Moderate increase in histone acetylation activates the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter and remodels its nucleosome structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10741-10746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya, N., A. Dey, S. Minucci, A. Zimmer, S. John, G. Hager, and K. Ozato. 1997. Retinoid-induced chromatin structure alterations in the retinoic acid receptor beta 2 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6481-6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanco, J. C. G., S. Minucci, J. M. Lu, X. J. Yang, K. K. Walker, H. W. Chen, R. M. Evans, Y. Nakatani, and K. Ozato. 1998. The histone acetylase P/CAF is a nuclear receptor coactivator. Genes Dev. 12:1638-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bresnick, E. H., S. John, D. S. Berard, P. Lefebvre, and G. L. Hager. 1990. Glucocorticoid receptor-dependent disruption of a specific nucleosome on the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter is prevented by sodium butyrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3977-3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell, M. J., S. Park, M. R. Uskokovic, M. I. Dawson, and H. P. Koeffler. 1998. Expression of retinoic acid receptor-beta sensitizes prostate cancer cells to growth inhibition mediated by combinations of retinoids and a 19-nor hexafluoride vitamin D3 analog. Endocrinology 139:1972-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon, P., S. H. Kim, C. Ulich, and S. Kim. 1994. Analysis of Tat function in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected low-level-expression cell lines U1 and ACH-2. J. Virol. 68:1993-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambon, P. 1996. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 10:940-954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, H. W., R. J. Lin, R. L. Schiltz, D. Chakravarti, A. Nash, L. Nagy, M. L. Privalsky, Y. Nakatani, and R. M. Evans. 1997. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell 90:569-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, H. W., R. J. Lin, W. Xie, D. Wilpitz, and R. M. Evans. 1999. Regulation of hormone-induced histone hyperacetylation and gene activation via acetylation of an acetylase. Cell 98:675-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, J. Y., J. Clifford, C. Zusi, J. Starrett, D. Tortolani, J. Ostrowski, P. R. Reczek, P. Chambon, and H. Gronemeyer. 1996. Two distinct actions of retinoid-receptor ligands. Nature 382:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherry, S. R., and D. Baltimore. 1999. Chromatin remodeling directly activates V(D)J recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10788-10793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba, H., J. Clifford, D. Metzger, and P. Chambon. 1997. Distinct retinoid X receptor retinoic acid receptor heterodimers are differentially involved in the control of expression of retinoid target genes in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3013-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciana, P., G. G. Braliou, F. G. Demay, M. von Lindern, D. Barettino, H. Beug, and H. G. Stunnenberg. 1998. Leukemic transformation by the v-ErbA oncoprotein entails constitutive binding to and repression of an erythroid enhancer in vivo. EMBO J. 17:7382-7394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clifford, J., H. Chiba, D. Sobieszczuk, D. Metzger, and P. Chambon. 1996. RXRα-null F9 embryonal carcinoma cells are resistant to the differentiation, anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of retinoids. EMBO J. 15:4142-4155. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cosma, M. P., T. Tanaka, and K. Nasmyth. 1999. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle- and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell 97:299-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Depoix, C., M. H. Delmotte, P. Formstecher, and P. Lefebvre. 2001. Control of retinoic acid receptor heterodimerization by ligand-induced structural transitions. a novel mechanism of action for retinoid antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9452-9459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Thé, H., A. Marchio, P. Tiollais, and A. Dejean. 1989. Differential expression and ligand regulation of the retinoic acid receptor alpha and beta genes. EMBO J. 9:429-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dey, A., S. Minucci, and K. Ozato. 1994. Ligand-dependent occupancy of the retinoic acid receptor beta 2 promoter in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:8191-8201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espinos, E., T. A. Le Van, C. Pomies, and M. J. Weber. 1999. Cooperation between phosphorylation and acetylation processes in transcriptional control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3474-3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrari, N., M. Pfahl, and G. Levi. 1998. Retinoic acid receptor γ1 (RAR γ(1) levels control RARβ2 expression in SK-N-BE2(c) neuroblastoma cells and regulate a differentiation-apoptosis switch. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6482-6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fryer, C. J., and T. K. Archer. 1998. Chromatin remodelling by the glucocorticoid receptor requires the BRG1 complex. Nature 393:88-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furumai, R., Y. Komatsu, N. Nishino, S. Khochbin, M. Yoshida, and S. Horinouchi. 2001. Potent histone deacetylase inhibitors built from trichostatin A and cyclic tetrapeptide antibiotics including trapoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:87-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glass, C. K., and M. G. Rosenfeld. 2000. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 14:121-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinzel, T., R. M. Lavinsky, T. M. Mullen, M. Soderstrom, C. D. Laherty, J. Torchia, W. M. Yang, G. Brard, S. D. Ngo, J. R. Davie, E. Seto, R. N. Eisenman, D. W. Rose, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman, A. D., D. Engelstein, T. Bogenrieder, C. N. Papandreou, E. Steckelman, A. Dave, R. J. Motzer, E. Dmitrovsky, A. P. Albino, and D. M. Nanus. 1996. Expression of retinoic acid receptor beta in human renal cell carcinomas correlates with sensitivity to the antiproliferative effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid. Clin. Cancer Res. 2:1077-1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horn, V., S. Minucci, V. V. Ogryzko, E. D. Adamson, B. H. Howard, A. A. Levin, and K. Ozato. 1996. RAR and RXR selective ligands cooperatively induce apoptosis and neuronal differentiation in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. FASEB J. 10:1071-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu, X., and M. A. Lazar. 1999. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 402:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang, E. Y., J. S. Zhang, E. A. Miska, M. G. Guenther, T. Kouzarides, and M. A. Lazar. 2000. Nuclear receptor corepressors partner with class II histone deacetylases in a Sin3-independent repression pathway. Genes Dev. 14:45-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser, A., H. Herbst, G. Fisher, M. Koenigsmann, W. E. Berdel, E. O. Riecken, and S. Rosewicz. 1997. Retinoic acid receptor beta regulates growth and differentiation in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 113:920-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kao, H. Y., M. Downes, P. Ordentlich, and R. M. Evans. 2000. Isolation of a novel histone deacetylase reveals that class I and class II deacetylases promote SMRT-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 14:55-66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korzus, E., J. Torchia, D. W. Rose, L. Xu, R. Kurokawa, E. M. Mcinerney, T. M. Mullen, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1998. Transcription factor-specific requirements for coactivators and their acetyltransferase functions. Science 279:703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon, H. J., T. Owa, C. A. Hassig, J. Shimada, and S. L. Schreiber. 1998. Depudecin induces morphological reversion of transformed fibroblasts via the inhibition of histone deacetylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3356-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, H. L., and T. K. Archer. 1994. Nucleosome-mediated disruption of transcription factor-chromatin initiation complexes at the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:32-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee, H. L., and T. K. Archer. 1998. Prolonged glucocorticoid exposure dephosphorylates histone H1 and inactivates the MMTV promoter. EMBO J. 17:1454-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lefebvre, B., C. Rachez, P. Formstecher, and P. Lefebvre. 1995. Structural determinants of the ligand-binding site of the human retinoic acid receptor alpha. Biochemistry 34:5477-5485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lefebvre, P., A. Mouchon, B. Lefebvre, and P. Formstecher. 1998. Binding of retinoic acid receptor heterodimers to DNA-a role for histone's NH2 termini. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12288-12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li, X. S., Z. M. Shao, M. S. Sheikh, J. L. Eiseman, D. Sentz, A. M. Jetten, J. C. Chen, M. I. Dawson, S. Aisner, A. K. Rishi, P. Gutierrez, L. Schnapper, and J. A. Fontana. 1995. Retinoic acid nuclear receptor beta inhibits breast carcinoma anchorage independent growth. J. Cell Physiol. 165:449-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, Y., M. -O. Lee, H.-G. Wang, Y. Li, Y. Hashimoto, M. Klaus, J. C. Reed, and X.-K. Zhang. 1996. Retinoic acid receptor β mediates the growth-inhibitory effect of retinoic acid by promoting apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1138-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michael, L. F., H. Asahara, A. I. Shulman, W. L. Kraus, and M. Montminy. 2000. The phosphorylation status of a cyclic AMP-responsive activator is modulated via a chromatin-dependent mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1596-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minucci, S., M. Leid, R. Toyama, J. P. Saintjeannet, V. J. Peterson, V. Horn, J. E. Ishmael, N. Bhattacharyya, A. Dey, I. B. Dawid, and K. Ozato. 1997. Retinoid X receptor (RXR) within the RXR-retinoic acid receptor heterodimer binds its ligand and enhances retinoid-dependent gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:644-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minucci, S., and K. Ozato. 1996. Retinoid receptors in transcriptional regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6:567-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minucci, S., D. J. Zand, A. Dey, M. S. Marks, T. Nagata, J. F. Grippo, and K. Ozato. 1994. Dominant negative retinoid-X receptor β inhibits retinoic acid-responsive gene regulation in embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:360-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moras, D., and H. Gronemeyer. 1998. The nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain: structure and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10:384-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mymryk, J. S., C. J. Fryer, L. A. Jung, and T. K. Archer. 1997. Analysis of chromatin structure in vivo. Methods 12:105-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagy, L., H. Y. Kao, D. Chakravarti, R. J. Lin, C. A. Hassig, D. E. Ayer, S. L. Schreiber, and R. M. Evans. 1997. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell 89:373-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagy, L., H. Y. Kao, J. D. Love, C. Li, E. Banayo, J. T. Gooch, V. Krishna, K. Chatterjee, R. M. Evans, and J. W. R. Schwabe. 1999. Mechanism of corepressor binding and release from nuclear hormone receptors. Genes Dev. 13:3209-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pergolizzi, R., V. Appierto, M. Crosti, E. Cavadini, L. Cleris, A. Guffanti, and F. Formelli. 1999. Role of retinoic acid receptor overexpression in sensitivity to fenretinide and tumorigenicity of human ovarian carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 81:829-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perissi, V., L. M. Staszewski, E. M. Mcinerney, R. Kurokawa, A. Krones, D. W. Rose, M. H. Lambert, M. V. Milburn, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1999. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes Dev. 13:3198-3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Protacio, R. U., G. Li, P. T. Lowary, and J. Widom. 2000. Effects of histone tail domains on the rate of transcriptional elongation through a nucleosome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8866-8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rachez, C., and L. P. Freedman. 2001. Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:274-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rastinejad, F. 2001. Retinoid X receptor and its partners in the nuclear receptor family. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanguedolce, M. V., B. P. Leblanc, J. L. Betz, and H. G. Stunnenberg. 1997. The promoter context is a decisive factor in establishing selective responsiveness to nuclear class II receptors. EMBO J. 16:2861-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith, C. L., and G. L. Hager. 1997. Transcriptional regulation of mammalian genes in vivo-a tale of two templates. J. Biol. Chem. 272:27493-27496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith, C. L., H. Htun, R. C. Wolford, and G. L. Hager. 1997. Differential activity of progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors on mouse mammary tumor virus templates differing in chromatin structure. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14227-14235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taunton, J., C. A. Hassig, and S. L. Schreiber. 1996. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science 272:408-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valcarcel, R., M. Meyer, M. Meisterernst, and H. G. Stunnenberg. 1997. Requirement of cofactors for RXR/RAR-mediated transcriptional activation in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1350:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Westin, S., R. Kurokawa, R. T. Nolte, G. B. Wisely, E. M. Mcinerney, D. W. Rose, M. V. Milburn, M. G. Rosenfeld, and C. K. Glass. 1998. Interactions controlling the assembly of nuclear-receptor heterodimers and coactivators. Nature 395:199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zou, C. P., W. K. Hong, and R. Lotan. 1999. Expression of retinoic acid receptor beta is associated with inhibition of keratinization in human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Differentiation 64:123-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]