Abstract

The homeodomain-containing transcription factor NKX3.1 is a putative prostate tumor suppressor that is expressed in a largely prostate-specific and androgen-regulated manner. Loss of NKX3.1 protein expression is common in human prostate carcinomas and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) lesions and correlates with tumor progression. Disruption of the murine Nkx3.1 gene results in defects in prostate branching morphogenesis, secretions, and growth. To more closely mimic the pattern of NKX3.1 loss that occurs in human prostate tumors, we have used Cre- and loxP-mediated recombination to delete the Nkx3.1 gene in the prostates of adult transgenic mice. Conditional deletion of one or both alleles of Nkx3.1 leads to the development of preinvasive lesions that resemble PIN. The pattern of expression of several biomarkers (Ki-67, E-cadherin, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins) in these PIN lesions resembled that observed in human cases of PIN. Furthermore, PIN foci in mice with conditional deletion of a single Nkx3.1 allele lose expression of the wild-type allele. Our results support the role of NKX3.1 as a prostate tumor suppressor and indicate a role for this gene in tumor initiation.

Multiple chromosomal abnormalities have been detected in prostate cancers (7), consistent with the hypothesis that multiple mutations must occur before progression from a preneoplastic condition to invasive carcinoma can occur. One of the most frequent chromosomal aberrations observed in prostate cancer involves loss of chromosomal region 8p12-22 (6, 24, 36). A gene or genes in this area are likely to be important in the initiation of prostate cancer, as loss of heterozygosity at this region also occurs in 63% of preinvasive prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) foci, which are the presumed precursors to prostate carcinoma (13). A strong candidate for a prostate tumor suppressor at this locus is the homeobox gene NKX3.1 (4, 19). The NKX3.1 gene maps within the minimal deleted region of 8p21 that is lost in prostate tumors (37). Although no mutations in the NKX3.1 gene have been found in a survey of prostate tumor specimens (37), loss of NKX3.1 protein expression has been observed in ∼40% of human prostate tumors and in ∼20% of PIN lesions (8). Furthermore, loss of NKX3.1 protein expression determined by immunohistochemistry correlated well with prostate tumor progression (8). These data suggest that NKX3.1 may be a prostate tumor suppressor, the second allele of which is inactivated by mechanisms other than mutations in the coding region.

In the mouse, deletion of the Nkx3.1 gene leads to developmental defects of the prostate gland, including defects in ductal branching morphogenesis, prostatic secretions, and epithelial hyperplasia and dysplasia (3, 30, 35). The prostatic epithelial hyperplasia and dysplasia that develops in Nkx3.1−/− mice supports a role for Nkx3.1 in growth suppression in the prostatic epithelium. However, this phenotype is confounded by the prominent developmental defects present in the prostates of these animals; thus, the precise role of Nkx3.1 in prostate carcinogenesis remains unclear (30, 35). To more closely approximate the pattern of somatic loss of NKX3.1 observed in human prostate tumors, we disrupted the Nkx3.1 gene in the prostates of mature mice with Cre-mediated recombination. To achieve this, we developed PSA-Cre transgenic mice, which express the Cre recombinase under control of a fragment of the human prostate-specific antigen (PSA) gene promoter. In PSA-Cre mice, the Cre recombinase is expressed after the mouse has attained puberty. Our results indicate that sudden loss of one or both Nkx3.1 alleles in the mature prostate predisposes the mouse to the development of lesions that closely resemble human PIN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of PSA-Cre transgenic mice.

We generated a transgenic construct (PSA-Cre) by using a PSA promoter fragment that targets expression specifically to the prostate (9) to drive expression of Cre recombinase. This construct consists of a 6-kb HindIII fragment of the human PSA promoter (9) and the nuclear-targeted Cre gene (20) followed by intron splice donor and polyadenylation sites for message stability provided by a modified human growth hormone (hGH) gene (10). Six independent transgenic founders were generated, and the two founders with the highest expression were used to establish transgenic lines. Founder mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice to establish transgenic lines. PSA-Cre transgenic mice were genotyped by PCR (forward primer, 5"-GCCTATATCCCAAAGGAACAGAAG-3"; reverse primer, 5"-CCTTCCTCTAGGTCCTTTAGGAGG-3"). Z/AP double reporter mice have been described previously (23). These mice constitutively express β-galactosidase in many tissues. After Cre-mediated recombination lacZ is deleted and alkaline phosphatase is expressed.

Generation of conventional Nkx3.1 knockout mice.

The loxP-targeting vector for generating a conditional allele (Nkx3.1flox) consists of a ∼5-kb 5" arm generated with long-range PCR, extending from approximately nucleotide −4000 through the first exon and ∼700 nucleotides into the intron. This fragment was cloned 5" of a PGK-neor cassette flanked by loxP sites. The 3" fragment was also generated by long-range PCR and contained a third loxP site introduced into the 3" untranslated region (UTR) in the same orientation as the two loxP sites flanking the PGK-neor cassette. The final vector was linearized and electroporated into ES cells, and targeted clones were obtained at a 2% frequency (2 out of 95). Chimeric males were bred with C57BL/6J females, and germ line transmission was obtained for both clones. Subsequent analysis was performed with the line established from clone 101. To generate Nkx3.1-deficient mice, we mated Actin-Cre transgenic mice (22) with mice containing the conditional Nkx3.1 allele (Nkx3.1flox). Actin-Cre mice express the Cre transgene in the germ line and are suitable for the induction of Cre-mediated deletion of loxP-flanked targets in the germ line. Mice were genotyped by Southern blot analysis and PCR with standard protocols. The sequence of the PCR primers used for Nkx3.1 genotyping as shown in Fig. 1A are the following: primer a, 5"-CCACCAAGTATCCGGCATAG-3"; primer b, 5"-TGCTCTCAGGGTTGATGCTC-3"; primer c, 5"-ATGAGGAAATTGCATCGCATTGTCT-3"; primer d, 5"-CCTAAACCACCTCTGCCTAC-3".

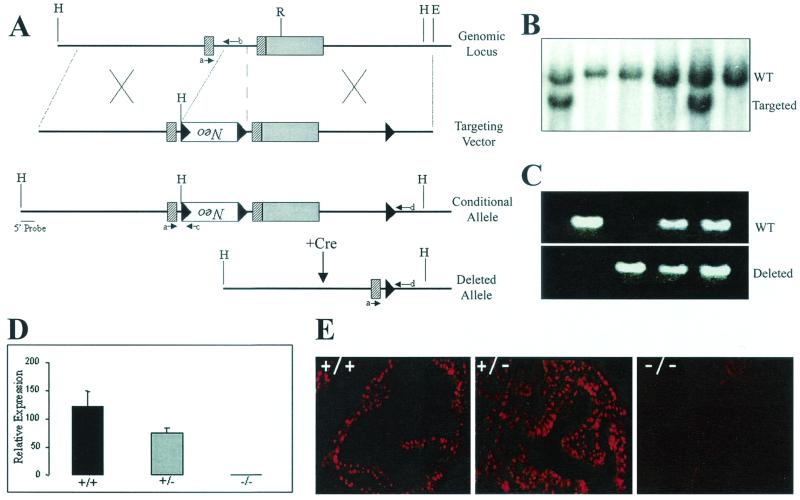

FIG. 1.

Generation of conditional and knockout Nkx3.1 alleles. (A) Maps of the Nkx3.1 genomic locus and the loxP-targeting vector designed to introduce a PGK-NeoR cassette flanked by two loxP sites and a third loxP site into the 3" UTR. Exons are denoted by rectangles and loxP sites are denoted by black triangles. The cross-hatched rectangles indicate coding regions, while the solid rectangle denotes the 3" UTR. Successful targeting yields a conditional (Nkx3.1flox) allele. Cre-mediated recombination results in deletion of the PGK-neor cassette and the homeodomain-containing second exon, yielding a knockout or deleted allele. Specific primers used to screen for the various alleles are indicated by small arrows labeled a through d. H, HindIII; R, EcoRI; E, EcoRI. (B) Southern blot analysis performed with a 5" external probe to detect homologous recombination resulting in the generation of a conditional (Nkx3.1flox) allele. This probe detects a 9-kb HindIII wild-type (WT) fragment and a 6-kb fragment from the targeted allele. (C) PCR analysis of genomic DNA from wild-type (Nkx3.1+/+), heterozygous (Nkx3.1+/−), and knockout (Nkx3.1−/−) mice generated by first mating mice containing the conditional allele (Nkx3.1flox) with Actin-Cre transgenic deleter mice (21) and subsequent mating of the heterozygous F1 animals. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Nkx3.1 expression in mouse prostates with the indicated genotypes. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of Nkx3.1 expression in the anterior prostates of wild-type, heterozygous, and knockout mice. Note that the heterozygous prostate is hyperplastic, explaining the multiple layers of Nkx3.1-positive luminal epithelial nuclei. Original magnifications, ×400.

Generation of conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice.

To obtain mice with prostate-specific deletion of Nkx3.1 we mated PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/+ mice with Nkx3.1−/flox mice. Subsequent interbreeding generated PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox, PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/+, and PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/− mice.

Histology.

Prostates for histology were processed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde or metharcan (methanol:chloroform:acetic acid, 60:30:10) (2). Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and were evaluated histologically by pathologists blinded to the genotypes of the animals (P. A. Humphrey and Z. Kaleem). β-Galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase stainings were performed essentially as described previously (23).

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (1, 15) with antigen retrieval by using boiling 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 20 to 30 min. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Ki-67 (1:2000; Vector, Burlingame, Calif.); mouse anti-human high-molecular-weight cytokeratins (1:50; Dako); mouse anti-E-cadherin (1:100; Transduction Laboratories). The Nkx3.1 antibody was raised against a mixture of two peptides, one N terminal (sequence, TPSKPLTSFLIQDILRD) and the other C terminal (sequence, KEEAFSRASLVSVYNS) to the conserved NKX3.1 homeodomain (Research Genetics, Birmingham, Ala.). These antibodies cross-reacted with both the mouse and human NKX3.1 proteins in immunohistochemistry and Western blot analyses. Affinity-purified sera were used at 1:20 dilution for immunohistochemistry.

Quantitative RT-PCR (TaqMan) analysis.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using the TaqMan instrument were performed as described previously (34). The hGH primers and probe used in assays to quantitate Cre transgene expression are the following: forward primer, 5"-CTCCAACAGGGAGGAAACACA-3"; reverse primer, 5"-GCGAAGACACTCCTGAGGAACT-3"; Taqman probe, 5"-CAGAAATCAACCTAGAGCTGCTCCGCATC-3". For analysis of Nkx3.1 expression, the following primers were used: forward primer, 5"-GCATAGCCCCGCGGA-3"; reverse primer, 5"-TAAGTCCCCTGGATTATGTTCACA-3".

RESULTS

Generation of conventional Nkx3.1-deficient mice.

To study the consequences of a lack of Nkx3.1 at various stages of mouse development, we used a Cre- and loxP-mediated recombination strategy. By generating mice containing a loxP-flanked Nkx3.1 allele, Nkx3.1 can be deleted either in the germ line or in any somatic tissue of interest by setting up matings with the appropriate Cre-expressing transgenic lines. We first generated a targeting vector containing a loxP-flanked PGK-neor cassette inserted in the Nkx3.1 intron and an additional loxP site in the 3" UTR of the gene (Fig. 1A). Successful targeting of ES cells with this vector (Fig. 1B) results in a conditional Nkx3.1 allele (Nkx3.1flox). The presence of the PGK-neor cassette in the intron did not impair the expression of the Nkx3.1 gene, and Nkx3.1flox/+ and Nkx3.1flox/flox mice developed normally without any abnormalities of the prostate (data not shown; also see Table 1). Cre-mediated recombination is expected to result in the deletion of the PGK-neor cassette and the homeodomain-containing second exon, yielding a null Nkx3.1 allele (Fig. 1A). To generate Nkx3.1-deficient mice, we mated Actin-Cre mice (22) with mice containing the conditional Nkx3.1 allele (NKx3.1flox). Analysis of tail DNA from the resultant animals showed successful recombination and subsequent transmission of the deleted Nkx3.1 allele through the germ line (Fig. 1C). Nkx3.1+/− mice from these matings were interbred to obtain homozygous null animals. Using quantitative RT-PCR and immunohistochemical analyses, we confirmed the loss of Nkx3.1 mRNA and protein expression in these Nkx3.1−/− mice (Fig. 1D and E, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Incidence of PIN in conditional Nkx3.1-deficient micea

| Genotype | n | Age (wks) | No. with PIN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA-Cre+Nkx3.1flox/+ | 11 | 15-35 | 4 (36) |

| PSA-Cre+Nkx3.1flox/flox | 9 | 21-25 | 8 (89) |

| Nkx3.1flox/+ | 2 | 23-28 | 0 (0) |

| Nkx3.1flox/flox | 4 | 21 | 0 (0) |

Prostates from animals of the indicated genotypes and ages were examined histologically for the presence of PIN. All PSA-Cre+Nkx3.1flox/+ and PSA-Cre+Nkx3.1flox/flox mice also showed prostatic epithelial hyperplasia.

Conventional Nkx3.1-deficient mice display prostatic epithelial hyperplasia and dysplasia.

Nkx3.1−/− animals developed normally and were fertile. Histological examination of the prostate glands of these mice and immunohistochemical analysis with Ki-67 antibody to assess proliferation demonstrated the presence of hyperplasia and dysplasia in both Nkx3.1+/− and Nkx3.1−/− animals (Fig. 2), in agreement with earlier reports (3, 30, 35). The presence of hyperplasia in heterozygous mutant animals indicates haploinsufficiency for this phenotype. These lesions, however, did not show evidence of progression to invasive carcinoma in mice of up to 1 year of age.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the prostates of conventional Nkx3.1-deficient mice. (A to F) Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of anterior prostates from 20-week-old Nkx3.1+/+(A and D), Nkx3.1+/− (B and E), and Nkx3.1−/− mice (C and F). Note the hyperplasia evident in sections from Nkx3.1+/− and Nkx3.1−/− mice. (G to I) Analysis of proliferation by Ki-67 staining of Nkx3.1+/+(G), Nkx3.1+/− (H), and Nkx3.1−/− (I) prostates. Magnification for panels A to C, ×100. Magnification for panels D to I, ×400.

Generation of transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase in the prostate.

To achieve conditional deletion of Nkx3.1 in the adult prostate gland, we first developed animals that express the Cre recombinase in the prostate after puberty. We used a 6-kb fragment of the human PSA promoter (9) to target expression of Cre to the mouse prostate. This PSA promoter fragment has been used previously by Cleutjens et al. to generate transgenic mice expressing the Escherichia coli lacZ gene in the prostate (9). In these animals, β-galactosidase expression was restricted to the luminal epithelial cells of the prostate and became detectable only after the animals had reached maturity (8 weeks). These features make this promoter ideal for use in strategies aimed at inducing mutations after prostate development is completed.

Since transgene expression driven by the PSA promoter is known to be restricted to the luminal epithelial cells of the prostate in transgenic mice (9), it was important to determine the cell-type-specific expression pattern of Nkx3.1 in the prostate as well. By using immunohistochemistry we found that in both adult human and adult mouse prostates Nkx3.1 expression was restricted to the terminally differentiated luminal epithelial cells, with no detectable expression in either the basal cells or the stromal compartment (Fig. 3A and B).

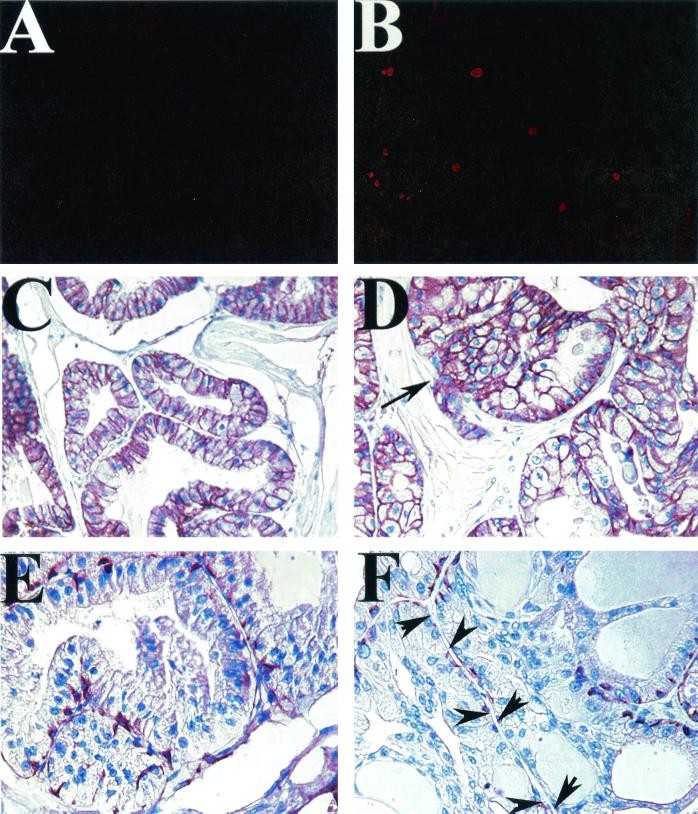

FIG. 3.

Generation and characterization of PSA-Cre transgenic mice. (A and B) Cell-type-specific expression of Nkx3.1 protein in the adult prostate. (A) NKX3.1 protein expression is restricted to the luminal epithelial cells of human prostate glands (brown nuclei) but not basal cells or stromal cells (blue nuclei). (B) Immunohistochemical localization of Nkx3.1 expression to luminal epithelial cell nuclei in mouse prostate (red). Basal cells stained with antibody to high-molecular-weight cytokeratins, 34βE12 (green), are negative for Nkx3.1 expression. (C to E) Assay of Cre activity in PSA-Cre;Z/AP double transgenic mice by double lacZ/alkaline phosphatase staining. The prostate of a control 8-week-old Z/AP-positive, PSA-Cre-negative transgenic mouse (C) shows widespread lacZ activity (blue) in the epithelium. The sections in panels D and E show the prostate of an 8-week-old double transgenic PSA-Cre;Z/AP animal demonstrating replacement of lacZ staining with alkaline phosphatase expression (pink) in luminal epithelial cells in which Cre-mediated recombination has occurred. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR (TaqMan) analysis for expression of the Cre transgene in prostates of mice from the two PSA-Cre transgenic lines (Cre3 and Cre13) and a normal prostate (N).

Transgenic mice were generated that express Cre under control of the PSA promoter fragment, and the two founders with the highest expression were used to establish transgenic lines (Fig. 3F). Subsequent experiments were performed with animals from line 13. To localize functional Cre expression in the prostate, we mated the PSA-Cre transgenic mice with Z/AP double reporter mice (23). Z/AP mice widely express the lacZ reporter constitutively. Cre-mediated excision removes the lacZ gene, allowing expression of the second reporter, the human alkaline phosphatase gene (23). Analysis of adult double transgenic PSA-Cre;Z/AP mice indicates functional Cre activity in the luminal epithelial cells of the prostate with a mosaic pattern (Fig. 3C to E). There was no evidence of Cre activity in either basal or stromal cells. Thus, these PSA-Cre transgenic mice are suitable for generating prostate-specific gene deletions.

Deletion of a single Nkx3.1 allele in adult prostates results in hyperplasia and dysplasia.

To determine the consequences of prostate-specific deletion of Nkx3.1 in the adult prostate, we generated and analyzed compound mutant mice with the following genotypes: PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1−/flox, PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox, and PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox. To determine the time of induction of Cre activity, we monitored Cre-mediated recombination of the conditional Nkx3.1 allele in the prostates of PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox mice. In these animals there was no evidence of Cre activity at 3 weeks of age, but Cre-mediated recombination was evident in 10-week- and 30-week-old animals (Fig. 4A). To determine the lobe-specific distribution of Cre activity, we dissected the prostatic lobes of a PSA-Cre+Nkx3.1flox/flox mouse. Recombination was readily apparent in the DNA isolated from the ventral and dorsolateral lobes of the prostate, with a much weaker signal present in the anterior lobe DNA (Fig. 4B). By contrast, none of the other tissues examined, including heart, liver, seminal vesicles, kidney, brain, and testis, showed evidence of recombination.

FIG. 4.

Temporal and prostate lobe-specific pattern of Cre activity in PSA-Cre transgenic mice. (A) Age-dependent Cre activity in PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox transgenic mice. Cre-mediated recombination, detected by PCR analysis of genomic DNA, is evident in the prostates of 10-week- and 30-week-old mice but not in the prostates of 3-week-old animals. (B) Detection of Cre-mediated recombination in various tissues of a 30-week-old PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox transgenic mouse by PCR. R, recombined allele; UR, unrecombined allele; Cre, PSA-Cre transgene; AP, anterior prostate; DLP, dorsolateral prostate; VP, ventral prostate; SV, seminal vesicle; T, testis; B, brain; K, kidney; L, liver; H, heart; w, water control.

Histological examination of the prostates of conditional Nkx3.1-deficient animals revealed the presence of focal epithelial hyperplasia and PIN, which were not observed in control PSA-Cre− animals (Fig. 5). The PIN lesions that developed in these animals resemble human PIN, showing enlarged nuclei of variable sizes and shapes with prominent nucleoli. Remarkably, PIN was observed in PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mice (Fig. 5 and Table 1), suggesting that the loss of a single Nkx3.1 allele is sufficient to initiate the development of PIN.

FIG. 5.

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and epithelial hyperplasia in conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice. (A) Prostate section from a control 28-week-old Nkx3.1+/flox mouse showing normal epithelium. (B to F) Epithelial hyperplasia and PIN (arrows) in the prostates of a 28-week-old PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mouse (B), a 23-week-old PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/− mouse (C), a 15-week-old PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mouse (D and E), and 25-week-old PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox transgenic mice (F through I). Original magnification for panels A to C, ×400; for panels D, F, G, and H, ×200; for panels E and I, ×600.

We further characterized these PIN lesions by examining their patterns of expression of several well-characterized biomarkers of human PIN (26). The lesions had a high Ki-67 labeling index (Fig. 6B), indicating active proliferation, which is a feature of human PIN lesions. In human prostate cancer, expression of the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin is lost in invasive tumors but is retained in preinvasive PIN lesions (17, 26). Similarly, the PIN lesions from conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice demonstrated membranous expression of E-cadherin (Fig. 6D). We next examined expression of the basal cell marker, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, with the antibody 34βE12. Basal cells are progressively lost as normal glandular prostatic epithelium evolves from PIN to carcinoma. Prostate carcinomas show complete loss of basal cells, while PIN lesions show partial disruption of the basal cell layer. In PIN lesions from conditional Nkx3.1-deficient animals, we observed areas of partial disruption of the basal cell layer (Fig. 6F), similar to what is observed in human PIN lesions.

FIG. 6.

Characterization of PIN lesions that develop in conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice. (A and B) Ki-67 immunohistochemistry, showing increased labeling in a PIN lesion from the prostate of a PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox mouse (B) relative to that in a normal prostate (A). (C and D) Pattern of E-cadherin expression by immunohistochemistry in normal prostatic epithelium (C) and a PIN lesion from a PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox mouse (D). Note the retention of membrane E-cadherin staining in the PIN lesion. The arrow in panel D points to a rare example of early microinvasion. (E and F) Staining of basal cells with antibody against high-molecular-weight cytokeratins (34βE12) in normal prostate (E) compared to that in conditional Nkx3.1-deficient PIN lesions (F). Note partial disruption of the basal cell layer in PIN lesions (arrows in panels F).

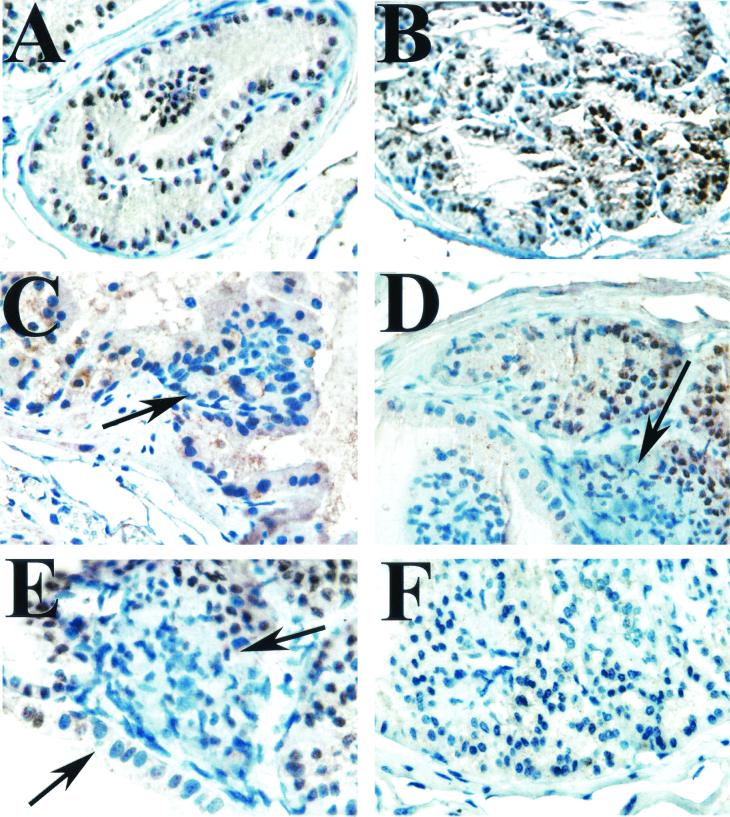

As we observed PIN in a subset of PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox animals, we investigated whether loss of the remaining wild-type Nkx3.1 allele is associated with the development of PIN in these animals. The small size, heterogeneity, and multifocal nature of the PIN lesions that develop in these mice makes analysis of purified DNA from cells isolated from within the PIN lesions impractical. We therefore used immunohistochemistry to determine if normal Nkx3.1 expression is retained in PIN foci in PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mice. We found that while cells in hyperplastic foci consistently express normal levels of Nkx3.1, many dysplastic cells in foci of PIN lack expression of the Nkx3.1 protein (Fig. 7). Analysis of 12 PIN lesions showed loss of Nkx3.1 expression in 11 foci, indicating the loss or silencing of the wild-type allele in PIN foci in PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mice. Thus, complete loss of Nkx3.1 expression may be important for the development or maintenance of these lesions.

FIG. 7.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Nkx3.1 expression in conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice. (A) Nkx3.1 expression in a benign prostate gland showing nuclear staining (brown) of the luminal epithelial cells. Hematoxylin was used as the counterstain (blue). (B) Hyperplastic glands from a PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mouse showing that these cells have largely retained expression of Nkx3.1 (brown nuclei). (C to E) PIN lesions from PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1+/flox mice showing cells that have lost expression of Nkx3.1 (blue nuclei, arrows) consistent with loss or silencing of the wild-type allele. (F) A lesion from a PSA-Cre+ Nkx3.1flox/flox transgenic mouse showing complete loss of Nkx3.1 expression.

DISCUSSION

Relatively little is known about the molecular events associated with the initiation of prostate carcinoma. PIN is widely regarded as a precursor of human prostate cancer (5). Our results, in conjunction with other recent reports (3, 8), have identified Nkx3.1 as a gene with an important role in the initiation of prostate cancer. As Nkx3.1 also plays a key role in the development and differentiation of the prostatic epithelium, it provides an important link between development and carcinogenesis in the prostate gland.

Several groups have recently reported on the generation of Nkx3.1-deficient mice by conventional gene knockout techniques (3, 30, 35). In all cases, the animals developed prostatic epithelial hyperplasia in the setting of developmental abnormalities of the prostate. Because of the prominence of the developmental abnormalities in Nkx3.1-deficient mice and the fact that the hyperplastic and dysplastic lesions that develop in these animals do not progress to frank carcinoma, the precise role of Nkx3.1 in prostate carcinogenesis has remained unclear (35). By using conditional gene targeting to delete Nkx3.1 specifically in the mature prostate, we circumvent the complicating effects of developmental abnormalities on the interpretation of the prostate phenotype of mice lacking Nkx3.1. This was possible because the PSA promoter fragment we used to drive Cre expression becomes active in transgenic mice only after puberty has been attained (9).

The lesions that developed in conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice resemble human preinvasive PIN in several respects. In addition to the histopathological similarities, the lesions showed a similar pattern of Ki-67 expression, E-cadherin localization, and partial disruption of basal cells, as is seen with human PIN lesions. Thus, conditional loss of Nkx3.1 in adult mice models the predicted consequences of loss of 8p21 in humans in the initiation of prostate cancer. All of the mice we studied with conditional deletion of one Nkx3.1 allele develop focal epithelial hyperplasia. In a subset of these animals PIN lesions were also observed, and these PIN lesions showed loss of expression of the wild-type allele as determined by immunohistochemistry. Thus, loss of one Nkx3.1 allele is sufficient to initiate epithelial hyperplasia, indicating haploinsufficiency for this phenotype. Further progression to PIN is associated with silencing of the second allele, as determined by loss of protein expression. The mechanisms by which loss of expression of the second allele is achieved are presently unclear, but they may involve promoter hypermethylation or posttranscriptional mechanisms. The latter possibility is particularly intriguing, as studies suggest a discordance between NKX3.1 transcript and protein levels in human prostate tumors (8, 27, 38).

We have shown that in both the mature human and mouse prostates, Nkx3.1 expression is limited to the luminal epithelial cell layer. Luminal epithelial cells of the prostate are terminally differentiated postmitotic cells and are believed to be renewed by stem cells from the basal cell compartment (18). Our results suggest that deletion of Nkx3.1 in the luminal cells is permissive for dedifferentiation and reentry into the cell cycle, subsequently leading to the development of PIN. However, during development precursor cells that are presumably also rapidly proliferating do express Nkx3.1 (3). The mechanism by which Nkx3.1 engages the cell cycle machinery in prostate cells in the different developmental stages of the prostate gland and in carcinoma is an interesting subject that warrants further investigation. Additional unanswered questions include whether the PIN lesions in conditional Nkx3.1 knockout mice can progress to invasive carcinoma and metastases with aging or other hormonal or genetic manipulations. We have observed only one isolated case of early microinvasion in analysis of more than 25 conditional Nkx3.1-deficient mice of up to 35 weeks of age. Further studies, which include variables such as aging for longer periods and hormonal treatment, are in progress to address this question.

Several transgenic mouse models of prostate cancer are presently available, most of which make use of prostate-specific promoter elements to direct expression of oncogenes to the prostate. Expression of the simian virus 40 T antigen has been targeted to various cell types in the prostate by using elements from the probasin promoter (16, 25), the C3 (1) promoter (32), the fetal Gγ-globin promoter (28), the gp91-phox promoter (33), and the cryptdin2 promoter (15). In these mice, tumor progression usually proceeds from PIN to invasive carcinoma and, in some cases, distant metastases.

Although T-antigen-derived models have proved useful in dissecting some of the pathways involved in prostate tumorigenesis, the fact that T antigen has no known role in the human disease has stimulated interest in the generation of newer models based on genes that are altered in human prostate cancer. Disruption of a few putative tumor suppressors in mice has been reported to result in prostatic epithelial hyperplasia and dysplasia. For example, mice carrying mutations in the Nkx3.1, Pten, Cdkn1, or Mxi1 gene all develop various degrees of prostatic hyperplasia and dysplasia (3, 12, 14, 29, 31). Notably, p27 (encoded by Cdkn1) and Pten have been reported to cooperate in prostate tumor suppression (11). Nevertheless, the roles of most of these tumor suppressor genes in the prostate gland may be masked by developmental defects or tumors that develop more rapidly in other organs, resulting in early lethality before the prostate pathology is fully developed. Conditional gene targeting will provide a useful methodology for circumventing these difficulties. To this end, our conditional Nkx3.1 mutant mice can provide a useful starting point for investigating the impact of prostate-specific deletions of additional tumor suppressor genes that may play important roles in distinct stages of prostate carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Martin for the Actin-Cre mice, A. Nagy for the Z/AP mice, and A. Gorodinsky and S. Audrain for technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA81564, the Association for the Cure of Prostate Cancer (CapCURE), the Urological Research Foundation (J.M.), and by the UAB-HHMI Junior Faculty Development Award (S.A.A.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulkadir, S. A., G. F. Carvalhal, Z. Kaleem, W. Kisiel, P. A. Humphrey, W. J. Catalona, and J. Milbrandt. 2000. Tissue factor expression and angiogenesis in human prostate carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 31:443-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdulkadir, S. A., Z. Qu, E. Garabedian, S. K. Song, T. J. Peters, J. Svaren, J. M. Carbone, C. K. Naughton, W. J. Catalona, J. J. Ackerman, J. I. Gordon, P. A. Humphrey, and J. Milbrandt. 2001. Impaired prostate tumorigenesis in Egr1-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 7:101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia-Gaur, R., A. A. Donjacour, P. J. Sciavolino, M. Kim, N. Desai, P. Young, C. R. Norton, T. Gridley, R. D. Cardiff, G. R. Cunha, C. Abate-Shen, and M. M. Shen. 1999. Roles for Nkx3.1 in prostate development and cancer. Genes Dev. 13:966-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bieberich, C. J., K. Fujita, W. W. He, and G. Jay. 1996. Prostate-specific and androgen-dependent expression of a novel homeobox gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271:31779-31782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostwick, D. G., D. Ramnani, and J. Qian. 2000. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: animal models 2000. Prostate 43:286-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bova, G. S., B. S. Carter, M. J. Bussemakers, M. Emi, Y. Fujiwara, N. Kyprianou, S. C. Jacobs, J. C. Robinson, J. I. Epstein, P. C. Walsh, et al. 1993. Homozygous deletion and frequent allelic loss of chromosome 8p22 loci in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 53:3869-3873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bova, G. S., and W. B. Isaacs. 1996. Review of allelic loss and gain in prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 14:338-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen, C., L. Bubendorf, H. J. Voeller, R. Slack, N. Willi, G. Sauter, T. C. Gasser, P. Koivisto, E. E. Lack, J. Kononen, O. P. Kallioniemi, and E. P. Gelmann. 2000. Loss of NKX3.1 expression in human prostate cancers correlates with tumor progression. Cancer Res. 60:6111-6115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleutjens, K. B., H. A. van der Korput, C. C. Ehren-van Eekelen, R. A. Sikes, C. Fasciana, L. W. Chung, and J. Trapman. 1997. A 6-kb promoter fragment mimics in transgenic mice the prostate-specific and androgen-regulated expression of the endogenous prostate-specific antigen gene in humans. Mol. Endocrinol. 11:1256-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford, P. A., Y. Sadovsky, K. Woodson, S. L. Lee, and J. Milbrandt. 1995. Adrenocortical function and regulation of the steroid 21-hydroxylase gene in NGFI-B-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4331-4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Cristofano, A., M. De Acetis, A. Koff, C. Cordon-Cardo, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2001. Pten and p27KIP1 cooperate in prostate cancer tumor suppression in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 27:222-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Cristofano, A., B. Pesce, C. Cordon-Cardo, and P. P. Pandolfi. 1998. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat. Genet. 19:348-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmert-Buck, M. R., C. D. Vocke, R. O. Pozzatti, P. H. Duray, S. B. Jennings, C. D. Florence, Z. Zhuang, D. G. Bostwick, L. A. Liotta, and W. M. Linehan. 1995. Allelic loss on chromosome 8p12-21 in microdissected prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer Res. 55:2959-2962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fero, M. L., E. Randel, K. E. Gurley, J. M. Roberts, and C. J. Kemp. 1998. The murine gene p27Kip1 is haplo-insufficient for tumour suppression. Nature 396:177-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garabedian, E. M., P. A. Humphrey, and J. I. Gordon. 1998. A transgenic mouse model of metastatic prostate cancer originating from neuroendocrine cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15382-15387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg, N. M., F. DeMayo, M. J. Finegold, D. Medina, W. D. Tilley, J. O. Aspinall, G. R. Cunha, A. A. Donjacour, R. J. Matusik, and J. M. Rosen. 1995. Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3439-3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper, M. E., E. Glynne-Jones, L. Goddard, P. Mathews, and R. I. Nicholson. 1998. Expression of androgen receptor and growth factors in premalignant lesions of the prostate. J. Pathol. 186:169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayward, S. W., and G. R. Cunha. 2000. The prostate: development and physiology. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 38:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He, W. W., P. J. Sciavolino, J. Wing, M. Augustus, P. Hudson, P. S. Meissner, R. T. Curtis, B. K. Shell, D. G. Bostwick, D. J. Tindall, E. P. Gelmann, C. Abate-Shen, and K. C. Carter. 1997. A novel human prostate-specific, androgen-regulated homeobox gene (NKX3.1) that maps to 8p21, a region frequently deleted in prostate cancer. Genomics 43:69-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolb, A. F., and S. G. Siddell. 1996. Genomic targeting with an MBP-Cre fusion protein. Gene 183:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewandoski, M., and G. R. Martin. 1997. Cre-mediated chromosome loss in mice. Nat. Genet. 17:223-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewandoski, M., K. M. Wassarman, and G. R. Martin. 1997. Zp3-cre, a transgenic mouse line for the activation or inactivation of loxP-flanked target genes specifically in the female germ line. Curr. Biol. 7:148-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lobe, C. G., K. E. Koop, W. Kreppner, H. Lomeli, M. Gertsenstein, and A. Nagy. 1999. Z/AP, a double reporter for cre-mediated recombination. Dev. Biol. 208:281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macoska, J. A., T. M. Trybus, P. D. Benson, W. A. Sakr, D. J. Grignon, K. D. Wojno, T. Pietruk, and I. J. Powell. 1995. Evidence for three tumor suppressor gene loci on chromosome 8p in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 55:5390-5395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masumori, N., T. Z. Thomas, P. Chaurand, T. Case, M. Paul, S. Kasper, R. M. Caprioli, T. Tsukamoto, S. B. Shappell, and R. J. Matusik. 2001. A probasin-large T antigen transgenic mouse line develops prostate adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma with metastatic potential. Cancer Res. 61:2239-2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers, R. B., and W. E. Grizzle. 1996. Biomarker expression in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Eur. Urol. 30:153-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ornstein, D. K., M. Cinquanta, S. Weiler, P. H. Duray, M. R. Emmert-Buck, C. D. Vocke, W. M. Linehan, and J. A. Ferretti. 2001. Expression studies and mutational analysis of the androgen regulated homeobox gene NKX3.1 in benign and malignant prostate epithelium. J. Urol. 165:1329-1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez-Stable, C., N. H. Altman, P. P. Mehta, L. J. Deftos, and B. A. Roos. 1997. Prostate cancer progression, metastasis, and gene expression in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 57:900-906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podsypanina, K., L. H. Ellenson, A. Nemes, J. Gu, M. Tamura, K. M. Yamada, C. Cordon-Cardo, G. Catoretti, P. E. Fisher, and R. Parsons. 1999. Mutation of Pten/Mmac1 in mice causes neoplasia in multiple organ systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1563-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider, A., T. Brand, R. Zweigerdt, and H. Arnold. 2000. Targeted disruption of the Nkx3.1 gene in mice results in morphogenetic defects of minor salivary glands: parallels to glandular duct morphogenesis in prostate. Mech. Dev. 95:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreiber-Agus, N., Y. Meng, T. Hoang, H. Hou, Jr., K. Chen, R. Greenberg, C. Cordon-Cardo, H. W. Lee, and R. A. DePinho. 1998. Role of Mxi1 in ageing organ systems and the regulation of normal and neoplastic growth. Nature 393:483-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibata, M. A., J. M. Ward, D. E. Devor, M. L. Liu, and J. E. Green. 1996. Progression of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive carcinoma in C3(1)/SV40 large T antigen transgenic mice: histopathological and molecular biological alterations. Cancer Res. 56:4894-4903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skalnik, D. G., D. M. Dorfman, D. A. Williams, and S. H. Orkin. 1991. Restriction of neuroblastoma to the prostate gland in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4518-4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Svaren, J., T. Ehrig, S. A. Abdulkadir, M. U. Ehrengruber, M. A. Watson, and J. Milbrandt. 2000. EGR1 target genes in prostate carcinoma cells identified by microarray analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:38524-38531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka, M., I. Komuro, H. Inagaki, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and S. Izumo. 2000. Nkx3.1, a murine homolog of drosophila bagpipe, regulates epithelial ductal branching and proliferation of the prostate and palatine glands. Dev. Dyn. 219:248-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vocke, C. D., R. O. Pozzatti, D. G. Bostwick, C. D. Florence, S. B. Jennings, S. E. Strup, P. H. Duray, L. A. Liotta, M. R. Emmert-Buck, and W. M. Linehan. 1996. Analysis of 99 microdissected prostate carcinomas reveals a high frequency of allelic loss on chromosome 8p12-21. Cancer Res. 56:2411-2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voeller, H. J., M. Augustus, V. Madike, G. S. Bova, K. C. Carter, and E. P. Gelmann. 1997. Coding region of NKX3.1, a prostate-specific homeobox gene on 8p21, is not mutated in human prostate cancers. Cancer Res. 57:4455-4459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu, L. L., V. Srikantan, I. A. Sesterhenn, M. Augustus, R. Dean, J. W. Moul, K. C. Carter, and S. Srivastava. 2000. Expression profile of an androgen regulated prostate specific homeobox gene NKX3.1 in primary prostate cancer. J. Urol. 163:972-979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]