Abstract

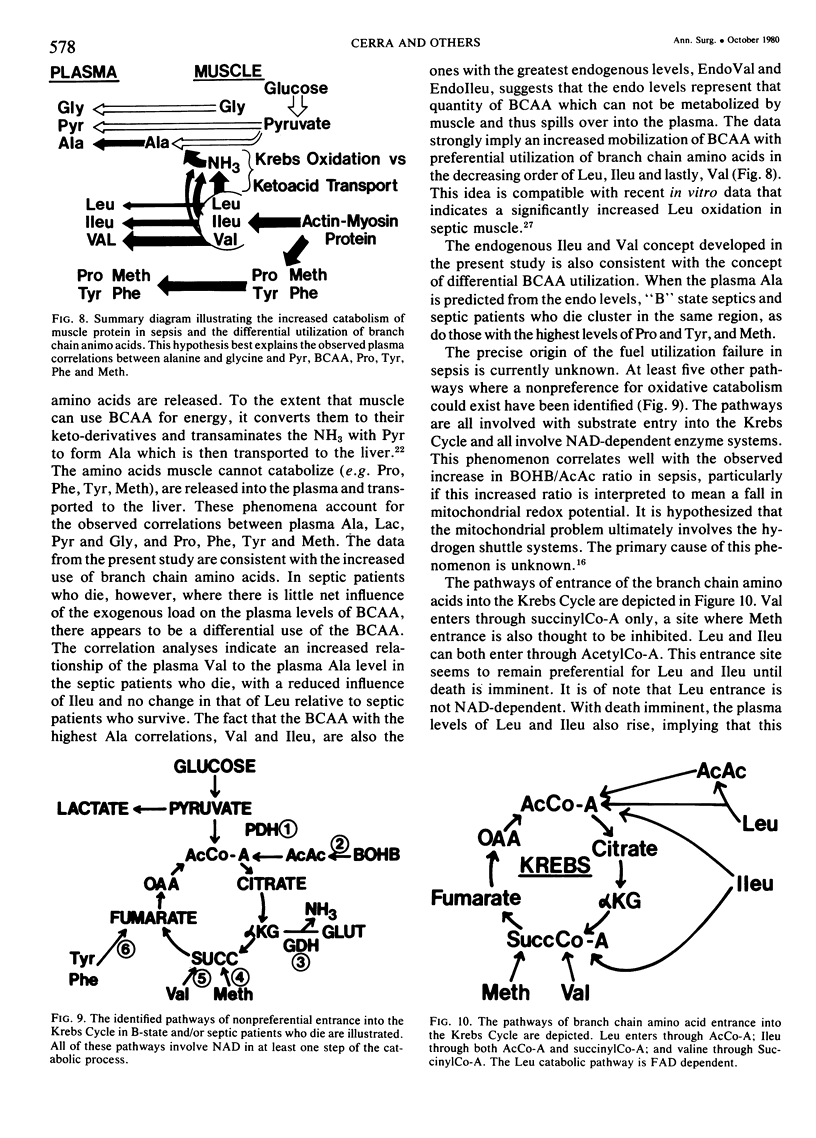

Forty-six patients with surgical sepsis were studied prospectively until death or survival to evaluate the effect of exogenous metabolic support on the observed plasma substrate levels and on the differential endogenous utilization of branch chain amino acids. There were no effects of administered glucose or colloid load. The administered amino acid load had little effect on substrate levels in patients who died; but significantly effected the observed levels of glycine, isoleucine, and methionine in patients who survived. Evidence is presented which suggests that fatal sepsis is associated with an increased release of endogenous valine and isoleucine into plasma, as well as increased plasma levels of tyrosine, proline, and methionine. These abnormalities are highly correlated with the increased levels of plasma alanine and occur at a time when the nonsurviving septic patient manifests a tendency toward reduced oxygen consumption and abnormal vascular tone relations--the septic B state. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that increased muscle protein catabolism is occurring with a differential utilization of branch chain amino acids and increased use of leucine and isoleucine and reduced use of valine. This autocannibalism of muscle mass appears to be the source of the increased plasma alanine and is little influenced by administered amino acid support in the absence of control of the septic process.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Askanazi J., Furst P., Michelsen C. B., Elwyn D. H., Vinnars E., Gump F. E., Stinchfield F. E., Kinney J. M. Muscle and plasma amino acids after injury: hypocaloric glucose vs. amino acid infusion. Ann Surg. 1980 Apr;191(4):465–472. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198004000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askanazi J., Rosenbaum S. H., Hyman A. I., Silverberg P. A., Milic-Emili J., Kinney J. M. Respiratory changes induced by the large glucose loads of total parenteral nutrition. JAMA. 1980 Apr 11;243(14):1444–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Border J. R., Chenier R., McManamy R. H., La Duca J., Seibel R., Birkhahn R., Yu L. Multiple systems organ failure: muscle fuel deficit with visceral protein malnutrition. Surg Clin North Am. 1976 Oct;56(5):1147–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier Y. A., Askanazi J., Elwyn D. H., Jeevanandam M., Gump F. E., Hyman A. I., Burr R., Kinney J. M. Effects of hypercaloric glucose infusion on lipid metabolism in injury and sepsis. J Trauma. 1979 Sep;19(9):649–654. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerra F. B., Caprioli J., Siegel J. H., McMenamy R. R., Border J. R. Proline metabolism in sepsis, cirrhosis and general surgery. The peripheral energy deficit. Ann Surg. 1979 Nov;190(5):577–586. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197911000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerra F. B., Siegel J. H., Border J. R., Peters D. M., McMenamy R. R. Correlations between metabolic and cardiopulmonary measurements in patients after trauma, general surgery, and sepsis. J Trauma. 1979 Aug;19(8):621–629. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197908000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerra F. B., Siegel J. H., Border J. R., Wiles J., McMenamy R. R. The hepatic failure of sepsis: cellular versus substrate. Surgery. 1979 Sep;86(3):409–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes G. H., Jr, O'Donnell T. F., Blackburn G. L., Maki T. N. Energy metabolism and proteolysis in traumatized and septic man. Surg Clin North Am. 1976 Oct;56(5):1169–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felig P. The glucose-alanine cycle. Metabolism. 1973 Feb;22(2):179–207. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(73)90269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley R. J., Duff J. H., Holliday R. L., Jones D., Marchuk J. B. Capillary muscle blood flow in human sepsis. Surgery. 1975 Jul;78(1):87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund H., Yoshimura N., Fischer J. E. The effect of branched chain amino acids and hypertonic glucose infusions on postinjury catabolism in the rat. Surgery. 1980 Apr;87(4):401–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund H., Yoshimura N., Lunetta L., Fischer J. E. The role of the branched-chain amino acids in decreasing muscle catabolism in vivo. Surgery. 1978 Jun;83(6):611–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long C. L., Kinney J. M., Geiger J. W. Nonsuppressability of gluconeogenesis by glucose in septic patients. Metabolism. 1976 Feb;25(2):193–201. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(76)90049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odessey R., Goldberg A. L. Oxidation of leucine by rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1972 Dec;223(6):1376–1383. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.223.6.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odessey R., Khairallah E. A., Goldberg A. L. Origin and possible significance of alanine production by skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1974 Dec 10;249(23):7623–7629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman N. B., Berger M. The formation of glutamine and alanine in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1974 Sep 10;249(17):5500–5506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan N. T. Metabolic adaptations for energy production during trauma and sepsis. Surg Clin North Am. 1976 Oct;56(5):1073–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J. H., Cerra F. B., Coleman B., Giovannini I., Shetye M., Border J. R., McMenamy R. H. Physiological and metabolic correlations in human sepsis. Invited commentary. Surgery. 1979 Aug;86(2):163–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J. H., Cerra F. B., Peters D., Moody E., Brown D., McMenamy R. H., Border J. R. The physiologic recovery trajectory as the organizing principle for the quantification of hormonometabolic adaptation to surgical stress and severe sepsis. Adv Shock Res. 1979;2:177–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannemacher R. W., Jr Key role of various individual amino acids in host response to infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977 Aug;30(8):1269–1280. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.8.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles J. B., Cerra F. B., Siegel J. H., Border J. R. The systemic septic response: does the organism matter? Crit Care Med. 1980 Feb;8(2):55–60. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198002000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmore D. W. Carbohydrate metabolism in trauma. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976 Nov;5(3):731–745. doi: 10.1016/s0300-595x(76)80048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]