Abstract

ColV plasmids have long been associated with the virulence of Escherichia coli, despite the fact that their namesake trait, ColV production, does not appear to contribute to virulence. Such plasmids or their associated sequences appear to be quite common among avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) and are strongly linked to the virulence of these organisms. In the present study, a 180-kb ColV plasmid was sequenced and analyzed. This plasmid, pAPEC-O2-ColV, possesses a 93-kb region containing several putative virulence traits, including iss, tsh, and four putative iron acquisition and transport systems. The iron acquisition and transport systems include those encoding aerobactin and salmochelin, the sit ABC iron transport system, and a putative iron transport system novel to APEC, eit. In order to determine the prevalence of the virulence-associated genes within this region among avian E. coli strains, 595 APEC and 199 avian commensal E. coli isolates were examined for genes of this region using PCR. Results indicate that genes contained within a portion of this putative virulence region are highly conserved among APEC and that the genes of this region occur significantly more often in APEC than in avian commensal E. coli. The region of pAPEC-O2-ColV containing genes that are highly prevalent among APEC appears to be a distinguishing trait of APEC strains.

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) strains are the etiologic agents of colibacillosis in birds, an important problem in the poultry industry (7). Along with uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) and the E. coli strain causing neonatal meningitis or septicemias, APEC strains fall under the category of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) (39). ExPEC strains are characterized by the possession of virulence factors that enable their extraintestinal lifestyle and make them distinct from commensal and diarrheagenic E. coli strains (39). Among APEC strains, the iroBCDEN locus (11), shown to encode the siderophore salmochelin in Salmonella enterica (16), the aerobactin operon (51), and the yersiniabactin operon (21) are iron acquisition systems thought to contribute to virulence. Other putative APEC virulence factors include those contributing to complement resistance, such as the increased serum survival gene (iss) (31, 33, 37); tsh, the temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin gene (34); and the presence of ColV plasmids (37). In fact, it appears that large virulence plasmids, including ColV plasmids, are a defining feature of the APEC pathotype (37, 44).

ColV and ColV plasmids have interested scientists for many years, with Gratia first describing ColV as “principle V” in 1925 (53). ColV plasmids, which encode ColV production, typically range in size from 80 to 180 kb (53) and encode traits such as aerobactin production (51) and complement resistance (31). Unlike other colicins, ColV itself is a small protein that is exported from the cell and behaves more like a microcin, disrupting the formation of cell membrane potential required for energy production (53). The ColV operon consists of genes for ColV synthesis (cvaC) and ColV immunity (cvi) and two genes for ColV export (cvaA and cvaB) (14). Other traits that have been localized to APEC ColV plasmids include iss (22, 48), the aerobactin operon (19, 23, 49, 51), and tsh (10, 23, 49).

ColV plasmids have been long associated with E. coli virulence (53). However, it was found that the production of the bacteriocin colicin V (ColV), the namesake trait of these plasmids, is not itself directly responsible for this association with virulence (36). Therefore, other traits encoded by these plasmids are likely responsible for their contributions to virulence. To date, the nature of this association has not been fully understood.

Several studies have demonstrated a link between APEC virulence and the possession of ColV plasmids (12, 13, 15, 23, 49, 50). In a previous study, we described a large ColV plasmid, from an APEC isolate, possessing the ColV and aerobactin operons iss, tsh, and traT (23, 24). More recently, Tivendale and colleagues (49) described a similar plasmid occurring in an APEC isolate. Such plasmids appear to be widespread among APEC strains, as gene prevalence studies have shown that many of the genes found on ColV plasmids occur in a large percentage of APEC populations (12, 37). In addition, several studies have directly linked ColV plasmids with the ability to cause disease in production animals (45, 55). Despite the importance of these plasmids with regard to APEC virulence, little sequence data exist for them, hindering further attempts to determine the mechanisms of ColV plasmid-mediated virulence in APEC. In the present study, DNA sequencing was performed on an APEC ColV plasmid to facilitate future studies of similar plasmids and their contributions to APEC virulence. Additionally, populations of APEC and avian commensal E. coli were examined for this plasmid's genes of interest using multiplex PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

pAPEC-O2-ColV was originally derived from APEC O2 (O2:K2) (23), which was isolated from the joint of a chicken with colibacillosis. In a prior study, APEC O2 (23) was mated with E. coli DH5α, an avirulent plasmidless strain, and the resulting transconjugant was used as a source of pAPEC-O2-ColV for the present study. Colinearity was previously demonstrated between the donor and transconjugant using Southern hybridizations, PCR, and agarose gel electrophoresis (23). pAPEC-O2-ColV is a large, conjugative plasmid encoding aerobactin production, ColV production, and complement resistance. Additionally, pAPEC-O2-ColV contains sequences homologous to iss, tsh, and traT (23).

Isolates used for the gene prevalence studies were obtained from a variety of sources within the United States, including Georgia, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Minnesota. Of the 794 isolates in this study, 595 originated from sites of infection from birds diagnosed with colibacillosis (APEC), and the remaining 199 isolates were commensal isolates obtained from fecal swabs of apparently healthy chickens and turkeys.

The positive control strain used for multiplex PCR was APEC O2. E. coli DH5α was used as a negative control for all of the genes studied (40). All bacterial strains and subclones were stored at −70°C in brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) with 10% glycerol until use (41).

DNA isolation and preparation for PCR.

pAPEC-O2-ColV DNA was initially obtained from a 1-liter culture grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) according to the method described previously by Wang and Rossman (52). Total DNA to be used as a template for PCR was obtained from APEC O2 and each of the 794 E. coli isolates using a boiling lysis procedure (22).

Shotgun library construction and sequencing.

Plasmid DNA was sheared, concentrated, and desalted using standard protocols (40). DNA was end repaired (30 min, 15°C; 100-μl reaction mixture consisting of 2 μg sheared DNA, 15 U T4 DNA polymerase, 10 U E. coli DNA polymerase [MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania], 500 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 10 μl Yellow Tango buffer [MBI Fermentas]), desalted, and tailed with an extra A residue (30 min, 50°C; 100 μl reaction mixture consisting of 2 μg sheared DNA, 50 μM each dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 2 mM dATP, 20 U Taq polymerase [MBI Fermentas], and 10 μl Yellow Tango buffer). A-tailed DNA was then size fractionated by electrophoresis, and the 1.5- to 2.5-kb fraction was isolated and purified using standard methods (40) prior to cloning into pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI).

Shotgun sequencing was performed by MWG Biotech, Inc. (Hedersberg, Germany). Briefly, plasmid clones were grown for 20 h in 1.8 ml LB broth supplemented with 200 μg ml−1 ampicillin in deep-well boxes. Plasmid DNA was prepared on a RoboPrep2500 DNA-Prep-Robot (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) using the NucleoSpin Robot-96 plasmid kit (Macherey & Nagel, Dueren, Germany) and sequenced from both ends with standard primers using BigDye Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The data were collected with ABI 3700 and ABI 3730xl capillary sequencers.

The Universal Genome Walker kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was initially used to close remaining gaps by creating inverse primers extending away from known sequences, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Problematic gaps were also subjected to pooled PCR using the technique described previously by Tettelin et al. (48). Amplicons were visualized on a 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA agarose gel run at 9 V/cm for 75 min. Appropriate size markers were also run for comparative purposes. Bands were excised from gels using a clean razor blade, and DNA exposure to ethidium bromide and UV light was kept at a minimum during this procedure. Excised gel fragments were purified using the PCR Clean-up kit (Promega). Purified amplicons were ligated into the pGem-T vector using the T/A Cloning kit (Promega). Ligation products were transformed into competent E. coli JM109 cells (Promega), and transformants were selected on medium containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (0.004%), IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (0.5 mM), and ampicillin (100 μg/ml). White colonies were picked and screened for insert size with the Colony Fast-Screen kit (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, WI). PCR was used to verify the presence of the desired insert DNA. Several transformants containing appropriate inserts were selected for each primer-walking reaction to ensure at least eightfold sequencing coverage.

Assembly and annotation.

Sequencing reads were assembled using SeqMan software from DNASTAR (Madison, WI). Open reading frames (ORFs) in the plasmid sequence were identified using GeneQuest from DNASTAR (Madison, WI), followed by manual inspection. Translated ORFs were then compared to known protein sequences using BLAST (NCBI, August 2005). Those with more than 25% identity, covering more than 60% of the matching protein sequence, were considered matches. Hypothetical proteins with more than 25% identity to one or more previously published proteins were classified as conserved hypothetical proteins, and ORFs with less than 25% identity to any published sequences were classified as hypothetical proteins. The G+C content of individual ORFs was analyzed using GeneQuest (DNASTAR). Insertion sequences (ISs) and repetitive elements were identified using IS FINDER (http://www-is.biotoul.fr/).

Gene prevalence studies.

Previously, Rodriguez-Siek et al. (37) examined 451 APEC and 104 avian commensal E. coli isolates for the presence of traits associated with ExPEC virulence. The present study expanded upon that work by adding 144 APEC and 95 commensal E. coli isolates to the isolate set and by screening all 794 isolates for eight additional plasmid-associated genes. Isolates were examined for the presence of pAPEC-O2-ColV-associated genes using several multiplex PCR panels. The genes studied included iss; tsh; cvaA, cvaB, and cvaC of the ColV operon; iutA of the aerobactin operon; iroN of the salmochelin operon; sitA of the sit ABC iron transport operon; hlyF; ompT, a gene encoding an outer membrane protease (37); eitA and eitB (E. coli iron transport), genes of a putative ABC iron transport system; and etsA and etsB (E.coli transport system), genes of a putative ABC transport system contained within pAPEC-O2-ColV.

All primers, annealing temperatures, and expected amplicon sizes are listed in Table 1. Primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Genes were amplified in three multiplex panels using a modified version of the multiplex PCR technique described previously by Rodriguez-Siek et al. (37, 38). PCR was performed with Amplitaq Polymerase Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Conditions used for PCR were as follows: 5 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 3 min at 72°C; and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. Amplicons were visualized on 2.0% Tris-acetate-EDTA agarose gels alongside a 1-kb ladder (Promega). Reactions were performed three times, and if an amplicon of the predicted size was produced in two of the three reactions, the isolate was considered positive for that gene.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in gene prevalence studies

| Primer | Gene | Sequence (5′-3′) | Tannealing (°C)a | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVAA F | cvaA | ATCCGGGCGTTGTCTGACGGGAAAGTTG | 63 | 319 | This study |

| CVAA R | ACCAGGGAACAGAGGCACCCGGCGTATT | ||||

| CVAB5′ F | cvaB | TGGCCACCCGGGCTCTTTCACTGGAGTT | 63 | 247 | This study |

| CVAB5′ R | ATGCGGGTCTGCAGGGTTTCCGACTGGA | ||||

| CVAB3′ F | cvaB | GGCCCGTGCCGCCTCCTATTTTA | 63 | 550 | This study |

| CVAB3′ R | TCCCGCACCGGAAGCACCAGTTAT | ||||

| CVAC F | cvaC | ATCCGATAAGATAAAAAGGAGAT | 63 | 416 | 23 |

| CVAC R | TAGACAATCCACCAAGAAGAAATA | ||||

| EITA F | eitA | ACGCCGGGTTAATAGTTGGGAGATAG | 60 | 450 | This study |

| EITA R | ATCGATAGCGTCAGCCCGGAAGTTAG | ||||

| EITB F | eitB | TGATGCCCCGCCAAACTCAAGA | 60 | 537 | This study |

| EITB R | ATGCGCCGGCCTGACATAAGTGCTAA | ||||

| ETSA F | etsA | CAACTGGGCGGGAACGAAATCAGGA | 60 | 284 | This study |

| ETSA R | TCAGTTCCGCGCTGGCAACAACCTAC | ||||

| ETSB F | etsB | CAGCAGCGCTTCGGACAAAATCTCCT | 60 | 380 | This study |

| ETSB R | TTCCCCACCACTCTCCGTTCTCAAAC | ||||

| HLY F | hlyF | GGCGATTTAGGCATTCCGATACTC | 60 | 599 | This study |

| HLYF R | ACGGGGTCGCTAGTTAAGGAG | ||||

| IRON F | iroN | AAGTCAAAGCAGGGGTTGCCCG | 63 | 667 | 37 |

| IRON R | GACGCCGACATTAAGACGCAG | ||||

| ISS F | iss | CAGCAACCCGAACCACTTGATG | 63 | 323 | 37 |

| ISS R | AGCATTGCCAGAGCGGCAGAA | ||||

| IUTA F | iutA | GGCTGGACATCATGGGAACTGG | 63 | 302 | 37 |

| IUTA R | CGTCGGGAACGGGTAGAATCG | ||||

| OMPT F | ompT | ATCTAGCCGAAGAAGGAGGC | 63 | 559 | 37 |

| OMPT R | CCCGGGTCATAGTGTTCATC | ||||

| SITA F | sitA | AGGGGGCACAACTGATTCTCG | 59 | 608 | 37 |

| SITA R | TACCGGGCCGTTTTCTGTGC | ||||

| TSH F | tsh | GGGAAATGACCTGAATGCTGG | 60 | 420 | 10 |

| TSH R | CCGCTCATCAGTCAGTACCAC |

Tannealing, annealing temperature.

Statistical analysis.

The null hypothesis that the proportion of APEC isolates possessing each gene examined was equal to the proportion of avian commensal E. coli isolates containing the same gene was tested using a Z test on the difference between the proportions (46). Additionally, this test was used to examine codon usage between genes of the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV and Escherichia coli K-12 strain MG1655 (3). The χ2 test was used for a univariate analysis of the significance of associations between two genes occurring in APEC (46). Gene pairs were classified as associated if they possessed a statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) χ2 value and as highly associated if they possessed a P value of ≤0.0001.

RESULTS

Sequencing of pAPEC-O2-ColV.

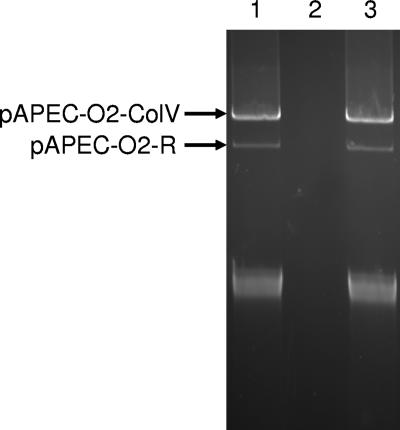

The focus of this study was pAPEC-O2-ColV, a ColV plasmid occurring in APEC strain O2. In addition to pAPEC-O2-ColV, APEC O2 also possesses pAPEC-O2-R, a 101-kb multidrug resistance plasmid that was sequenced in a previous study (25). Previously, pAPEC-O2-ColV was cotransferred with pAPEC-O2-R into the plasmidless, avirulent strain E. coli DH5α (Fig. 1), resulting in a transconjugant showing an increase in complement resistance and virulence towards chick embryos compared to the recipient strain (23). The recipient strain that acquired APEC O2's plasmids also became resistant to ampicillin, tetracycline, streptomycin, trimethoprim, a quaternary ammonium compound, sulfamethoxazole, and silver nitrate, all of which are encoded on pAPEC-O2-R (23, 24). It was this multidrug-resistant transconjugant, containing both APEC O2 plasmids, that served as a source of the pAPEC-O2-ColV DNA used in the present study.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of supercoiled plasmid DNA from the donor strain, APEC O2 (lane 1), E. coli DH5α, the recipient strain (lane 2), and their transconjugant (lane 3). Note that the donor and transconjugant contain pAPEC-O2-R and pAPEC-O2-ColV.

Approximately 2,000 shotgun clones of pAPEC-O2-ColV were arrayed, sequenced, and assembled using the SeqMan program contained within the LaserGene package (DNASTAR).Assembly and subsequent gap closure resulted in the generation of three contiguous sequences: a 93,609-bp region containing numerous virulence-associated genes (Table 2 and Fig. 2), a 48,458-bp region encompassing the full transfer region of pAPEC-O2-ColV (Table 3), and a 37,428-bp region containing genes mostly encoding hypothetical proteins of unknown function (Table 4). The sizes of the three contiguous sequences generated totaled 179,495 bp. Several efforts were made to close remaining gaps between contiguous sequences, including the use of pooled PCR with inverse primers extending away from the ends of the contiguous sequences, long-range PCR in an effort to span gaps and repetitive elements, and genomic walking from the ends of the contiguous sequences. Regardless of the method used, large identical repetitive elements prevented total gap closure. Restriction maps, generated from study of similar ColV plasmids (1, 53), were used to orient the contiguous sequences and close the remaining gaps. Based on all these data, a circular map of pAPEC-O2-ColV was created (Fig. 3), but PCR efforts to close the final three gaps, all of which involved IS1 elements and their flanking sequences, were unsuccessful.

TABLE 2.

Predicted coding sequences of the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV

| Coding region | Coordinates | Closest protein match | GenBank match (accession no.) | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sitA | 475-1389 | Periplasmic iron-binding protein | NP_753508 | 98 |

| sitB | 1389-2216 | Iron transport protein, ATP-binding component | NP_753507 | 98 |

| sitC | 2213-3049 | Iron transport protein, inner membrane component | NP_753506 | 98 |

| sitD | 3068-3925 | Iron transport protein, inner membrane component | NP_707259 | 96 |

| orf5 | 4557-4294 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_863027 | 100 |

| orf6 | 4500-4760 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAH64819 | 100 |

| orf7 | 4827-5099 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf8 | 5283-5549 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| shiF | 6865-6002 | Putative membrane transport protein | CAH64817 | 92 |

| shiG | 6758-7186 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAD44745 | 89 |

| iucA | 7189-8970 | Aerobactin biosynthesis protein | CAA53707 | 98 |

| iucB | 8971-9918 | N-Hydroxylysine acetylase (aerobactin synthesis) | CAH64815 | 100 |

| iucC | 9918-11660 | Aerobactin biosynthesis protein | CAH64814 | 100 |

| iucD | 11657-12934 | l-Lysine 6-monooxygenase | CAE55773 | 99 |

| iutA | 13016-15217 | Ferric aerobactin receptor | CAE55774 | 99 |

| orf16 | 15342-15563 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| insA | 15597-15872 | IS1 ORF 1 | AAO49621 | 100 |

| insB | 15791-16294 | IS1 ORF 2 | AAO49620 | 100 |

| orf19 | 16819-16472 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAO49619 | 100 |

| orf20 | 17475-17119 | Putative transposase | AAO49618 | 100 |

| orf21 | 17516-17812 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAR05705 | 100 |

| repA | 18221-19198 | RepFIB replication protein | AAO49616 | 99 |

| int | 20223-19483 | Site-specific integrase | AAR05703 | 100 |

| hlyF | 22659-20906 | Avian hemolysin | AAO49613 | 99 |

| orf25 | 23048-23332 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| ompT | 24374-23421 | Outer membrane protein, protease precursor | P58603 | 74 |

| orf27 | 24478-24867 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf28 | 25498-25235 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf29 | 26063-25647 | Transposase | NP_754365 | 71 |

| orf30 | 26108-26359 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAD58552 | 77 |

| orf31 | 26340-26582 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| etsA | 27778-28965 | ABC transporter, efflux pump protein | EAM16000 | 50 |

| etsB | 29067-30902 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | NP_716452 | 56 |

| etsC | 30906-32276 | ABC transporter, outer membrane component | NP_716543 | 59 |

| orf35 | 33002-32658 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf36 | 33051-33452 | IS4 | NP_415755 | 85 |

| orf37 | 33323-33832 | Putative transposase | AA008349 | 73 |

| orf38 | 34660-35448 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf39 | 35450-37711 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAG75082 | 87 |

| orf40 | 37928-37677 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf41 | 39513-38464 | Putative transposase | YP_026156 | 89 |

| orf42 | 40416-40045 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf43 | 41196-40927 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf44 | 42870-41431 | Putative transposase | CAD09789 | 98 |

| orf45 | 43330-43013 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAP42494 | 100 |

| orf46 | 44656-43463 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAP42493 | 100 |

| insD | 46016-45111 | IS2 transposase | NP_755496 | 99 |

| orf48 | 46384-45974 | Conserved hypothetical protein within IS2 | NP_709899 | 100 |

| iss | 47031-47339 | Increased serum survival and complement resistance | AAD41540 | 100 |

| orf50 | 47634-47377 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf51 | 48216-48506 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAP42476 | 99 |

| orf52 | 48546-49208 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAP42475 | 95 |

| orf53 | 50016-50285 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAP42495 | 100 |

| iroB | 50436-51599 | IroB, glycosyltransferase | NP_753168 | 100 |

| iroC | 51613-55398 | IroC, ABC transporter protein | AAN76099 | 100 |

| iroD | 55502-56731 | IroD, ferric enterochelin esterase | AAN76100 | 100 |

| iroE | 56816-57772 | IroE, hydrolase | AAN76101 | 100 |

| iroN | 59994-57817 | IroN, siderophore receptor | AAN76093 | 100 |

| orf59 | 60246-60509 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf60 | 61702-60920 | Phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase | NP_753137 | 98 |

| ybbA | 62405-62064 | Conserved hypothetical protein | BAA75101 | 79 |

| ybaA | 62745-62464 | Conserved hypothetical protein | BAA75100 | 90 |

| orf63 | 62812-63186 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| cvaA | 64264-65175 | Colicin V secretion protein | CAA40743 | 100 |

| cvaB | 65150-67264 | Colicin V secretion protein | CAA40744 | 100 |

| cvaC | 67745-67434 | Colicin V synthesis protein | CAA40746 | 100 |

| cvi | 67959-67723 | Colicin V immunity protein | CAA40745 | 100 |

| orf68 | 68150-68896 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAA11512 | 98 |

| orf69 | 69217-69966 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAA11511 | 93 |

| orf70 | 70443-70949 | Putative IS element | AAG56195 | 100 |

| orf71 | 71078-71479 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAA11510 | 100 |

| orf72 | 71463-71981 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAA11509 | 100 |

| orf73 | 72143-73732 | Putative transposase | NP_933162 | 66 |

| orf74 | 73916-74506 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf75 | 74758-74456 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf76 | 74971-75228 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf77 | 75664-75215 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAF76758 | 99 |

| tsh | 79906-75773 | Temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin | CAA11507 | 99 |

| orf79 | 80523-80029 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CAA11506 | 100 |

| insN | 80511-80915 | IS911 transposase | NP_414789 | 97 |

| orf81 | 80872-81999 | IS30 transposase | CAC39292 | 99 |

| orf82 | 82145-82510 | IS91 transposase | CAD87831 | 100 |

| orf83 | 82465-82743 | Conserved hypothetical protein within IS91 | NP_707640 | 92 |

| orf84 | 82979-83989 | Putative invertase | AAR07688 | 80 |

| orf85 | 84382-84675 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf86 | 85105-84623 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| eitA | 85516-86514 | ABC iron transporter, periplasmic-binding protein | CAC48456 | 45 |

| eitB | 86514-87551 | ABC iron transporter, permease protein | NP_793040 | 57 |

| eitC | 87548-88312 | ABC iron transporter, ATP-binding protein | CAB92552 | 83 |

| eitD | 88324-89556 | ABC iron transporter, membrane protein | CAG74456 | 68 |

| orf91 | 89891-89634 | Colicin E2 immunity protein | AAN28374 | 86 |

| orf92 | 90227-89892 | Truncated colicin E2 structural protein | AAN28373 | 74 |

| orf93 | 90221-90466 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf94 | 90611-91033 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf95 | 91950-91540 | Conserved hypothetical protein | JC5053 | 88 |

| orf96 | 92302-91916 | Truncated IS629 transposase | AAK18492 | 99 |

| orf97 | 92564-92223 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAG56914 | 95 |

| orf98 | 92632-93411 | Putative transposase | AAG18473 | 100 |

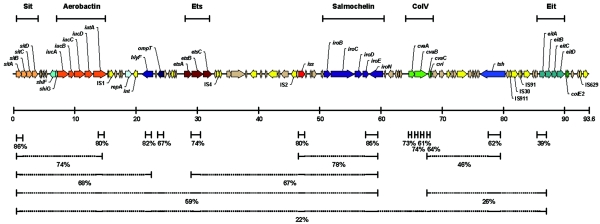

FIG. 2.

Drawing of the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV, drawn to scale. The ruler below the image indicates sizes in kilobase pairs. The locations of primers used for PCR are shown immediately below the ruler, and below that are prevalences of the individual genes of the region among APEC strains. The layers of dotted lines are the prevalences of groupings of virulence region genes among APEC strains. For instance, sitA and iutA occur individually in 86% and 80% of the APEC strains tested, respectively; they occur together in 74% of the APEC strains tested. However, sitA, iutA, and hlyF only occur together in 68% of the APEC strains tested. Based on these prevalence data, it appears that this virulence region is composed of two subregions, one that is conserved among the APEC strains used in this study and the other that is more variable in occurrence. The divide between these two subregions appears to occur within the cvaB gene. Genes are color coded as follows: orange, sit operon; red-orange, aerobactin operon; light blue, repA; dark blue, hlyF and ompT; maroon, etsABC; red, iss; purple, salmochelin operon; green, ColV operon; blue, tsh; turquoise, eitABCD; yellow, mobile elements.

TABLE 3.

Predicted coding sequences of the transfer region of pAPEC-O2-ColV

| Coding region | Coordinates | Closest protein match | GenBank match (accession no.) | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| insB | 1208-942 | Partial IS1 element | NP_707996 | 98 |

| orf100 | 1863-2141 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf101 | 2393-2878 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf102 | 3382-2927 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf103 | 3328-3897 | Conserved hypothetical protein (partial) | YP_190157 | 98 |

| orf104 | 3737-4972 | Conserved hypothetical protein (partial) | YP_190157 | 97 |

| psiB | 5199-5633 | Plasmid SOS inhibition protein B | YP_190156 | 99 |

| psiA | 5630-6349 | Plasmid SOS inhibition protein A | YP_190155 | 100 |

| orf107 | 7732-7247 | Conserved hypothetical protein | YP_190150 | 84 |

| orf108 | 7826-8233 | Conserved hypothetical protein (partial) | YP_190149 | 100 |

| orf109 | 8046-8759 | Conserved hypothetical protein (partial) | YP_190149 | 94 |

| orf110 | 9373-9056 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAO49513 | 100 |

| orf111 | 9705-9394 | Conserved hypothetical protein | YP_190148 | 85 |

| traM | 9982-10365 | TraM conjugative protein | YP_190147 | 100 |

| traJ | 10561-11243 | TraJ conjugative protein | YP_190146 | 100 |

| traY | 11248-11568 | TraY conjugative protein | AAL23481 | 84 |

| traA | 11621-11965 | TraA fimbrial protein precursor | CAA31973 | 92 |

| traL | 11980-12291 | TraL conjugative protein | AA049518 | 100 |

| traE | 12313-12879 | TraE conjugative protein | YP_190142 | 97 |

| traK | 13273-12809 | TraK (partial) | NP_052950 | 74 |

| traB | 13601-15030 | TraB (internal join) | YP_190140 | 100 |

| traP | 14962-15534 | TraP conjugative protein | YP_190139 | 98 |

| traV | 16094-16609 | TraV conjugative protein | YP_190136 | 98 |

| traR | 16792-16965 | TraR conjugative protein | YP_190135 | 100 |

| yfhA | 16958-17431 | YfhA | YP_190134 | 100 |

| traC | 18242-20872 | TraC conjugative protein | YP_190131 | 99 |

| traW | 21252-21905 | TraW conjugative protein | AAO49528 | 99 |

| traU | 21905-22873 | TraU conjugative protein | YP_190128 | 100 |

| trbC | 22879-23520 | TrbC conjugative protein | BAA97958 | 99 |

| traN | 23517-25325 | TraN conjugative protein | YP_190126 | 99 |

| trbE | 25349-25609 | TrbE conjugative protein | YP_190125 | 94 |

| traF | 25602-26345 | TraF conjugative protein | YP_190124 | 100 |

| trbA | 26361-26708 | TrbA conjugative protein | YP_190123 | 100 |

| traQ | 26827-27111 | TraQ conjugative protein | YP_190122 | 100 |

| trbB | 27198-27641 | TrbB conjugative protein | YP_190121 | 100 |

| trbJ | 27571-27933 | TrbJ conjugative protein | YP_190120 | 99 |

| traH | 27930-29306 | TraH conjugative protein | YP_190119 | 100 |

| traG | 29372-32125 | TraG conjugative protein | YP_190118 | 100 |

| traS | 32140-32643 | TraS conjugative protein | NP_052977 | 79 |

| traT | 32576-33406 | TraT conjugative protein | YP_190117 | 100 |

| traD | 33659-35857 | TraD conjugative protein | AAT85682 | 97 |

| traI | 35857-41127 | TraI conjugative protein | YP_190115 | 99 |

| traX | 41147-41893 | TraX conjugative protein | YP_190114 | 100 |

| yieA | 41952-41812 | YieA | YP_190113 | 100 |

| finO | 42915-43475 | FinO fertility inhibition protein | YP_190112 | 100 |

| orf144 | 43604-43816 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_052985 | 100 |

| yigB | 44049-44522 | YigB | YP_190110 | 100 |

| orf146 | 44815-45405 | Conserved hypothetical protein | YP_190108 | 98 |

| repB | 45645-45905 | RepB replication protein | AAP79039 | 100 |

| repA1 | 46355-45936 | RepA1 replication protein | AAO49555 | 99 |

| repA3 | 45999-46184 | RepA3 replication protein | CAA23641 | 99 |

| orf150 | 46299-47054 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| repA4 | 47417-47665 | RepA4 replication protein | AAO49650 | 89 |

| orf152 | 47757-47984 | Hypothetical protein |

TABLE 4.

Predicted coding sequences of the hypothetical region of pAPEC-O2-ColV

| Coding region | Coordinates | Closest protein match | GenBank match (accession no.) | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf153 | 311-168 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| insB | 478-287 | Partial IS1 transposase | AAO49620 | 90 |

| orf155 | 1007-831 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf156 | 1208-1047 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf157 | 1437-1721 | Partial transposase | NP_753136 | 84 |

| orf158 | 1723-1983 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_753135 | 91 |

| orf159 | 2086-1964 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf160 | 2419-2285 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf161 | 3782-2820 | Putative kinase | AAG54666 | 94 |

| orf162 | 5360-3861 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf163 | 6438-5473 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAC73424 | 90 |

| orf164 | 6354-6653 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf165 | 6740-6994 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| yahF | 8447-6898 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AAG54664 | 82 |

| yahE | 9255-8407 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_752377 | 60 |

| yahD | 9946-9341 | Putative transcription factor | AAC73421 | 71 |

| yahB | 10336-11265 | Putative transcriptional regulator | NP_757373 | 84 |

| orf170 | 11691-11533 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf171 | 12012-12263 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf172 | 12521-12366 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf173 | 12666-12427 | Conserved hypothetical protein within IS911 | AAG58804 | 66 |

| insB | 13119-13622 | IS1 transposase | AAO49620 | 100 |

| orf175 | 13778-13557 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf176 | 14742-15032 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| insD | 16596-15622 | IS2 transposase | AAX22093 | 91 |

| orf178 | 17398-17066 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf179 | 17453-17674 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf180 | 18722-17832 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_756620 | 91 |

| orf181 | 20020-18800 | Putative permease | NP_756621 | 94 |

| orf182 | 20435-20046 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_756622 | 91 |

| yahI | 21408-20452 | YahI, putative carbamate kinase | NP_756623 | 96 |

| yahG | 22876-21401 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_756624 | 96 |

| yahF | 24448-22822 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_756626 | 97 |

| orf186 | 25338-24477 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_756627 | 96 |

| orf187 | 26014-25646 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NP_756628 | 95 |

| orf188 | 26590-26955 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| repB | 28232-27501 | RepB replication protein | CAA77820 | 68 |

| orf190 | 28386-28237 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf191 | 28472-28299 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf192 | 28736-28605 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf193 | 29045-30058 | ParA partitioning protein | AAC82736 | 97 |

| orf194 | 30055-31026 | ParB partitioning protein | AAC82737 | 91 |

| umuC | 32287-31346 | UmuC UV protection protein | AAL23540 | 93 |

| orf196 | 32292-32480 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf197 | 32589-32422 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| orf198 | 32836-35281 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| insB | 36147-35644 | IS1 transposase | AAO49620 | 99 |

| orf200 | 36811-36479 | Conserved hypothetical protein | BAA22516 | 88 |

| insC | 37166-36801 | IS2 conserved hypothetical protein | AAL57520 | 100 |

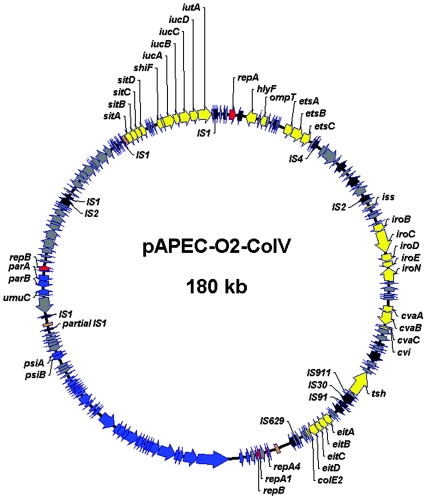

FIG. 3.

Circular genetic map of pAPEC-O2-ColV, drawn to scale. Arrows indicate predicted genes and their directions of transcription. Yellow arrows indicate virulence-associated genes. Blue arrows indicate genes involved in plasmid transfer and maintenance. Red arrows indicate genes involved in plasmid replication. Gray arrows indicate genes of unknown function. Black arrows indicate mobile genetic elements. Orange slashes indicate gaps in contiguous sequence that were unable to be resolved due to IS1 elements.

The 93-kb putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV was found to contain tsh, a temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin (34); the ColV operon, encoding ColV production (14); iss, the increased serum survival gene involved in complement resistance (18, 23, 33); ompT, an outer membrane protease (37); and hlyF, a putative hemolysin previously identified in an APEC strain (GenBank accession no. AF155222) (Table 2). It also contained several operons associated with iron acquisition including the salmochelin operon, a siderophore iron acquisition system (16); the aerobactin operon, another siderophore system (6); and the sit operon, an ABC transport system (57). Other genes not previously identified as occurring in APEC were also found within this contiguous sequence, including etsA and etsB (E. coli transport system, a novel set of genes identified in this study), genes of a putative ABC transport system; shiF and shiG, genes previously found on a pathogenicity island (PAI) of Shigella flexneri (30); and four genes, eitA to eitD (E. coli iron transport), also novel genes identified in this study, that may encode a putative iron uptake system.

The F-like transfer region of pAPEC-O2-ColV spanned 31,911 bp and contained 30 genes (Table 3). A second replicon of pAPEC-O2-ColV that closely resembles the RepFIIA plasmid replicon (GenBank accession no. M16167) separated the F-like transfer region from the putative virulence region on its 5′ end. On the 3′ end of the transfer region were approximately 38 kb of genes, encoding hypothetical proteins or conserved hypothetical proteins, for which no functional assignment was available. Overall, the three contiguous sequences of pAPEC-O2-ColV contained 201 predicted ORFs (Tables 2 to 4). Of these coding regions, 47% were found to be of unknown function and 25% were ORFs sharing no significant identity with any available database proteins.

The putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV was found to begin with the sit ABC transport system, which was followed by the iutABCD and iutA genes of the aerobactin operon and then the RepFIB replicon, containing the repA gene (Fig. 2) (42). Adjacent to the RepFIB region on its 3′ end were the insertion sequence IS1, a site-specific integrase, and etsABC, three genes novel to APEC and sharing protein identity with a putative ABC transport system found in Shewanella oneidensis (17) (Table 2). Following etsABC were an assortment of intact and partial IS elements, including IS4 and IS2, followed by iss and the iroBCDEN genes of the salmochelin operon. Adjacent to the salmochelin operon on its 3′ end were the cvaABC and cvi genes of the ColV operon and tsh. tsh was surrounded by mobile genetic elements, including a large putative transposase on its 5′ end and IS911, IS30, IS91, and an invertase on its 3′ end. Following these mobile elements on the 3′ end of tsh were the eitABCD genes, novel to APEC and sharing protein identity with a putative ABC iron transport system from the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae (4). An intact ColE2 immunity gene, a partial ColE2 structural gene, and remnants of an IS629 element flanked this system on its 3′ end.

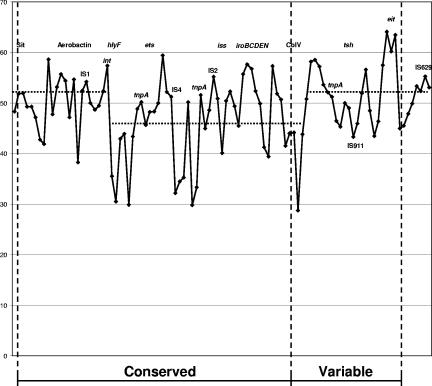

Overall, this putative virulence region was found to encode two siderophore systems, three putative ABC transport systems, and ColV production and was found to contain iss, hlyF, ompT, tsh, and the RepFIB replicon. Thus, pAPEC-O2-ColV appears to be a member of the IncFIB incompatibility group, based upon BLAST homology and alignment with proteins of the RepFIB replicon. The overall G+C content of the cluster was 48%. Analysis of individual ORFs within this putative virulence region revealed that the 45-kb region from hlyF through cvi possessed a G+C content of 46%, and its 5′- and 3′-flanking regions possessed G+C contents of 52% (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

G+C content of individual ORFs within the 93.6-kb virulence cluster of pAPEC-O2-ColV. Dashed lines indicate the average G+C contents of regions of the virulence cluster. Three regions could be discerned based on proximity, gene prevalence, and G+C content (Table 4). The first, running from sitA through int, had an average G+C ratio of 52%. The second region from hlyF through cvi had an average G+C ratio of 46%. The final region, running from ORF67 through IS629, had an average G+C content of 52%. The conserved portion of the virulence cluster contained these first two regions, while the variable portion of the cluster was composed of part of the second region and all of the third region.

Comparative genomics of cluster-related sequences revealed some interesting deviations from previously published patterns. For instance, the aerobactin operon was found to be chromosomally integrated in other pathogens, such as within the SHI-2 and SHI-3 PAIs of Shigella strains (30, 35) and within the chromosome of UPEC strain CFT073 (54). Similarly, the sit iron transport system also appeared to be chromosomally located in other strains, including within a PAI of Salmonella (20) and on the chromosome of UPEC strain CFT073 (54). Comparison of the virulence cluster with previously published sequences from a UPEC transmissible plasmid, p300 (47), and PAI III from UPEC strain 536 (8) revealed that the salmochelin operon was conserved among all three regions. iss was found near the salmochelin operon in a highly conserved arrangement within p300, and tsh and remnants of the ColV operon were also found within portions of PAI III536. Codon usage analysis was performed to test the hypothesis that different patterns of usage occur between genes of the E. coli chromosome andgenes of the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV. When frequency distributions for each codonwere examined, 50 out of the 62 codons in pAPEC-O2-ColV's putative virulence region had distributions significantly different from those in E. coli K-12 strain MG1655. A bias was also observed towards rare codons in genes of the putative virulence region, with higher frequencies observed towards AUA (Ile), AGA (Arg), CGA (Arg), CGG (Arg), and CCC (Pro).

Prevalence of plasmid-related genes in avian E. coli.

Multiplex PCR was used to examine 595 APEC and 199 avian commensal E. coli strains for the presence of 13 genes found within the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV. Results indicated that all of the genes examined were significantly more likely to be found among the APEC isolates than among the commensal isolates (Table 5). Representative genes of the salmochelin, sit, and aerobactin operons, as well as iss and hlyF, occurred in 80% or more of APEC isolates; the putative iron transport genes etsA and etsB occurred in 74.3% of the APEC isolates examined; the putative ABC iron transport system genes eitA and eitB occurred in 38.8% of the APEC isolates examined; cvaA and the 5′ end of cvaB occurred in 72.5% and 73.9% of the APEC isolates; and cvaC, tsh, ompT, and the 3′ end of cvaB occurred in more than 60% of the APEC isolates. Among the avian commensal E. coli isolates, the least prevalent gene sequences were the 3′ end of cvaB as well as cvaC, occurring approximately 19% of the time. iroN, hlyF, iss, etsA, etsB, eitA, eitB, ompT, cvaA, and the 5′ end of cvaB all occurred approximately one-quarter of the time among the commensal isolates. iutA, tsh, and sitA occurred 34%, 41%, and 48% of the time, respectively. None of the genes surveyed occurred more than 50% of the time among avian commensal E. coli isolates, and all of the genes surveyed were found in APEC isolates significantly more often than in the commensal isolates.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of gene prevalence between APEC and avian commensal E. coli isolates

| Gene | % of isolates containing gene

|

Z score | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APEC (n = 595) | Avian commensal E. coli (n = 199) | |||

| sitA | 86.0 | 47.7 | 11.04 | <0.0001 |

| iroN | 85.4 | 25.1 | 16.12 | <0.0001 |

| hlyF | 81.7 | 27.1 | 14.28 | <0.0001 |

| iss | 80.0 | 26.1 | 13.98 | <0.0001 |

| iutA | 79.5 | 34.2 | 11.92 | <0.0001 |

| etsA | 74.3 | 25.1 | 12.37 | <0.0001 |

| etsB | 74.3 | 25.1 | 12.37 | <0.0001 |

| cvaB (5′) | 73.9 | 26.1 | 12.03 | <0.0001 |

| cvaA | 72.5 | 25.6 | 11.75 | <0.0001 |

| ompT | 67.2 | 24.1 | 10.63 | <0.0001 |

| cvaC | 64.4 | 19.1 | 11.10 | <0.0001 |

| tsh | 62.2 | 40.7 | 5.31 | <0.0001 |

| cvaB (3′) | 61.2 | 19.1 | 10.31 | <0.0001 |

| eitA | 38.8 | 23.6 | 3.89 | <0.0001 |

| eitB | 38.8 | 23.6 | 3.89 | <0.0001 |

Gene prevalences were also plotted along the map of the putative virulence region (Fig. 2) to determine if a pattern in the occurrence of these genes could be discerned. Based on the resulting plot, it appeared that the putative virulence region could be split into “conserved” and “variable” portions. The “conserved” portion spanned the area from sitA through the 5′ end of cvaB. All of the genes of this region screened via PCR occurred individually in more than 67% of the APEC isolates tested and together in 59% of the APEC strains tested. The remainder of the putative virulence region, running from the 3′ end of cvaB through eitA, appeared to be more variable among APEC isolates. The genes within this portion of the putative virulence region occurred less often individually than those of the “conserved” portion, and they occurred together in only 26% of the APEC isolates. Additionally, a univariate analysis of the significance of associations between gene pairs was performed for all genes assayed with multiplex PCR. Based on resulting P values obtained using a χ2 plot, gene pairs were defined as unassociated (P > 0.05), significantly associated (P≤ 0.05), or highly associated (P ≤ 0.0001) (Table 6). Out of 105 possible gene combinations, 84 were classified as highly associated, 16 were classified as significantly associated, and only 5 were classified as unassociated. All of the gene combinations that were not highly associated involved genes of the “variable” portion of the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV.

TABLE 6.

Correlation of gene pairs among 595 APEC strains isolated from poultry

| Gene | % of APEC isolates possessing both genesa

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iroN | hlyF | iss | iutA | etsA | etsB | cvaB (5′) | cvaA | ompT | cvaC | tsh | cvaB (3′) | eitA | eitB | |

| sitA | 78.9a** | 75.7** | 74.4** | 73.9** | 69.2** | 69.2** | 68.2** | 67.1** | 60.4* | 59.4** | 58.9** | 56.4* | 36.9** | 36.9** |

| iroN | 76.9** | 77.7** | 75.4** | 69.6** | 69.6** | 68.2** | 66.9** | 60.9** | 61.7** | 57.4** | 56.7** | 35.4* | 35.4* | |

| hlyF | 74.4** | 71.5** | 72.0** | 72.0** | 66.1** | 64.7** | 57.4* | 58.6** | 54.9** | 56.1** | 35.3* | 35.3* | ||

| iss | 72.0** | 67.7** | 67.7** | 65.4** | 64.2** | 57.2** | 59.7** | 54.6** | 55.2** | 33.8* | 33.8* | |||

| iutA | 69.6** | 69.6** | 66.2** | 64.4** | 57.4** | 61.1** | 57.8** | 55.3** | 37.0** | 37.0** | ||||

| etsA | 74.5** | 63.7** | 61.9** | 52.9* | 57.6** | 54.5** | 53.3** | 36.3** | 36.3** | |||||

| etsB | 63.7** | 61.9** | 52.9* | 57.6** | 54.5** | 53.3** | 36.3** | 36.3** | ||||||

| cvaB (5′) | 73.9** | 53.4* | 55.9** | 52.6** | 62.1** | 32.9** | 32.9** | |||||||

| cvaA | 53.1* | 55.2** | 50.9** | 61.6** | 32.1* | 32.1* | ||||||||

| ompT | 47.9** | 41.8 | 47.4** | 26.5 | 26.5 | |||||||||

| cvaC | 45.6** | 50.1** | 29.5** | 29.5** | ||||||||||

| tsh | 52.6* | 34.8** | 34.8** | |||||||||||

| cvaB (3′) | 27.2 | 27.2 | ||||||||||||

| eitA | 39.4** | |||||||||||||

*, Statistically significant correlation among a gene pair (P ≤ 0.05); **, highly significant correlation among a gene pair (P ≤ 0.0001).

In an effort to explain the differences in prevalence between the “conserved” and “variable” portions of the putative virulence region, the sequence was examined for mobile elements positioned in such a way that they could render the variable region mobile and subject to loss from the cluster. It was not readily apparent from this examination how insertion sequence-mediated transposition might have produced the observed gene prevalences (Fig. 2 and Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Regions of the putative virulence region of pAPEC-O2-ColV delineated by proximity, similarity in gene prevalence, and G+C content

| Expanse of region | Prevalence of genes of expanse occurring together (%) | Average G+C content of expanse (%) | Associated mobile elements within expanse |

|---|---|---|---|

| sitA-hlyFa | 68 | 52 | IS1, int |

| etsA-cvaB (5′ end)a | 67 | 46 | IS4, IS2 |

| cvaB (3′ end)-eitAb | 26 | 52 | IS911, IS30, IS91, IS629 |

| Overall | 22 | 48 | IS1, int, IS4, IS2, IS911, IS30, IS91, IS629 |

“Conserved” portion of putative virulence region.

“Variable” portion of putative virulence region.

So too, it was thought that a G+C analysis of these regions might identify regions of the putative virulence region that share a common origin (Fig. 4). The overall G+C content for the contiguous sequences of pAPEC-O2-ColV was 49.2%. The G+C content of the putative virulence region was 48%. Based on G+C analysis of individual ORFs within the putative virulence region, three distinct regions could be discerned. These regions included one region running from sitA through int, with an average G+C content of 52%; one region running from hlyF through cvi, with an average G+C content of 46%; and a third region running from a putative insertion sequence on the 3′ end of cvi through IS629, with an average G+C content of 52%. The first two regions composed the “conserved” portion of pAPEC-O2-ColV's putative virulence region, while a part of the second region and all of the third region comprised the region's “variable” portion. Therefore, it appeared that the conserved portion of the putative virulence region may be composed of two regions of diverse origins.

DISCUSSION

ColV plasmids have long been associated with the virulence of E. coli in general (2, 45, 53) and APEC in particular (9, 10, 13, 15, 23, 24, 49, 55, 56). Interestingly, their association with virulence is not due to their namesake trait of ColV production (36), indicating that genes other than those involved in ColV production must be responsible for this association. Remarkably, despite the long recognition of the association of ColV plasmids and virulence, a ColV plasmid has never been sequenced in its entirety. Here, the first sequence of a ColV plasmid is presented, revealing a 93-kb putative virulence region containing numerous known or putative virulence genes that may account for the association of ColV plasmids with virulence. This region contains several genes or operons previously described as putative APEC virulence factors, including tsh (34), the salmochelin operon (11), and iss (18, 23, 31, 37, 49). This cluster also contains three iron acquisition and transport systems in addition to the salmochelin operon. The sit operon is an ABC transport system, involved in the metabolism of iron and manganese, originally identified in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (57) and more recently identified in APEC using genomic subtractive hybridization and signature-tagged mutagenesis (28, 43). However, this study is the first report of sit occurring near the aerobactin operon on a ColV plasmid. Two additional putative ABC transport systems are found within the cluster, eitABCD and etsABC. This is also the first report of these systems occurring in E. coli. eitABCD shares low translated protein identity to an iron transport system from the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae (4), and etsABC shares identity to an ABC transport system found in Shewanella oneidensis (17). Further work is in progress to determine the functionality of these putative ABC transporters. This putative virulence region also possesses several other genes whose roles have not yet been determined, including shiF, shiG, hlyF, ompT, and several genes which, when translated, encode hypothetical proteins.

Of particular interest is the presence of four sets of genes previously associated with iron acquisition and transport within this 93-kb putative virulence region. Such apparent redundancy suggests that iron acquisition plays an important role in APEC virulence. In addition to the potential iron acquisition and transport systems of APEC O2 presented in this study, this strain also possesses the fyuA and irp2 genes of the yersiniabactin operon and ireA, both of which have been associated with iron acquisition and ExPEC virulence (21, 36, 37). In order to understand APEC's virulence mechanisms, it would seem important to determine if these iron acquisition systems really areredundant or if they have nonoverlapping, specific purposes, such as ensuring that E. coli has an adequate iron supply throughout the different stages of infection. For example, it has been suggested that the sit operon only acts as an iron uptake system during intracellular infection, because this is the only host location in which iron is at a concentration suitable for the ABC transport system to function effectively (5). However, sit, like many of these systems, may be multifunctional, effecting transport of different compounds, such as manganese, at various stages of infection (5). Further studies to assess these iron acquisition and transport genes, their functionality, the conditions of their expression, and their importance to APEC virulence at all stages of infection could prove very helpful in understanding the pathogenesis of avian colibacillosis.

While many individual APEC virulence factors have been identified on large plasmids (10, 19, 49), this is the first report, to our knowledge, of a plasmid-encoded putative virulence region among APEC strains or on a ColV plasmid. Previously, Rodriguez-Siek et al. (37) examined 451 APEC and 104 commensal E. coli isolates for the possession of more than 35 different ExPEC virulence-associated genes. Among the genes examined were iss, cvaC, tsh, sitA, iutA, ompT, and iroN, all found on pAPEC-O2-ColV. The present study expanded that research through the addition of isolates and gene targets to the screening procedures. The genes added to this study included those of the etsABCD cluster, the eitABC cluster, the ColV operon, and hlyF. Many of the genes of this region, including iss, iroN, iutA, sitA, and hlyF, occurred in more than 80% of the APEC isolates and in only about 25% of the avian commensal E. coli isolates examined (Table 5). These results are striking and support the idea that this putative virulence region may be a widespread characteristic of APEC. However, this region does not appear to be intact in all APEC strains, as the prevalence studies show that genes within the “variable” portion of this region (the 3′ ends of cvaB, cvaC, tsh, eitA, and eitB) occur less often than genes of the “conserved” portion of the region, including sitA, iroN, iss, iutA, hlyF, etsA, etsB, cvaA, and the 5′ end of cvaB. Also, it is possible that some genes of this putative virulence region might be found elsewhere in the APEC genome, such as on non-ColV plasmids or within PAIs on the bacterial chromosome. Indeed, alternative locations for some of these genes have been identified in UPEC strains. For instance, UPEC strain 536 contains PAI III536, which shows some similarity to pAPEC-O2-ColV in both sequence and gene arrangement, leading us to hypothesize that this virulence cluster might be located on the bacterial chromosome in some APEC isolates (8). Interestingly, this UPEC PAI contains the salmochelin operon, tsh, and remnants of the ColV operon, suggesting the possibility that this PAI originated as a ColV plasmid that integrated into the chromosome in a fashion similar to that described previously by Oelschlaeger et al. (32). Also, the iro-iss region of pAPEC-O2-ColV shows 99.9% sequence identity with a UPEC non-ColV plasmid (47), further supporting the idea that the cluster can occur in different locations in the E. coli genome. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that ColV plasmids readily integrate into the bacterial chromosome to form Hfr strains and that these cointegrates lose the ability to produce ColV (26). Results of our gene prevalence studies also support this possibility, revealing “conserved” and “variable” portions of the putative virulence region that join within the cvaB gene. Analysis of UPEC PAI III536 showed that it contained remnants of the ColV operon and that it contained a truncated cvaB gene. These results, along with the above-described observations, cause us to speculate that cvaB might be a breakpoint during the integration of ColV-associated sequences into other locations in the bacterial genome. Indeed, our gene prevalence data indicate that cvaA and the 5′ end of cvaB occur among APEC isolates at rates similar to that of the “conserved” portion of the putative virulence region, while the 3′ end of cvaB and its downstream genes occur among APEC isolates at much lower rates (Fig. 2).

Thus, ColV plasmids might be an evolutionary intermediate for the development of chromosomal PAIs that contain APEC virulence factors (26, 32). Gene prevalence data obtained from this study and that of Rodriguez-Siek et al. (37) support this model of APEC evolution. That is, several isolates can be found that might serve as examples for each stage of development from ColV-encoded virulence traits through PAI-encoded virulence traits. For example, among our collection of APEC isolates, some isolates containing cvaC of the ColV operon and all other virulence genes sought in this study were found, suggesting that these isolates contain plasmids similar to pAPEC-O2-ColV. Also, examples of isolates possessing all of the genes in this study except those of the ColV operon are also found, suggesting that these genes may occur on non-ColV plasmids or within the bacterial chromosome. Isolates can also be found among the APEC strains with PAI III536-like patterns. That is, there are APEC strains containing the salmochelin operon, tsh, and cvaA and the 5′ end of cvaB but lacking the 3′ end of cvaB and other components of the putative virulence region.

With regard to characterizing the APEC pathotype, of particular interest is the “conserved” portion of the putative virulence region encompassing sitABCD, the aerobactin and salmochelin operons, hlyF, the etsABC transport system, ompT, iss, cvaA, and the 5′ portion of cvaB. Selected genes within this span of sequence appear to be highly conserved among APEC isolates, occurring in about 75% or more of the APEC isolates examined. This conserved portion of this putative APEC virulence region may be a defining feature of the APEC pathotype and perhaps a requirement for APEC virulence, regardless of whether or not it occurs on ColV plasmids. Further study will be needed to assess the role of this region in the pathogenesis of avian colibacillosis.

The transfer region of pAPEC-O2-ColV flanks the 3′ end of the putative virulence cluster and bears strong similarities to the transfer region of the F plasmid (27). This region is found on the 3′ end of an IS1 element following two genes involved in plasmid maintenance and stability, psiA and psiB (29). Downstream of this region, and separating it from the 5′ end of pAPEC-O2-ColV's virulence cluster, is a 45-kb stretch of DNA that bears no significant matches within the GenBank databases. This region is noteworthy due to its novel nature, and further work is required to determine the functions of the hypothetical proteins it encodes and their role, if any, in APEC virulence.

In sum, DNA sequencing of pAPEC-O2-ColV, a ColV virulence plasmid occurring in APEC O2, revealed the location of many APEC virulence genes (putative or known), several genes or operons novel to E. coli, and a variety of mobile genetic elements within a putative 93-kb virulence cluster. Portions of this putative virulence region commonly occurred among APEC isolates but not avian commensal E. coli isolates. Genes occurring in the “conserved” portion of this region may occur in the absence of an intact ColV operon in some avian E. coli isolates, which may provide hints as to the evolutionary development of ColV plasmids and chromosomal PAIs. The presence of this virulence cluster appears to discriminate most APEC isolates from commensal E. coli isolates, indicating that this region may prove useful as a target for identification of pathogenic E. coli. Genes within this region likely account for the long association of ColV plasmids with virulence.

The DNA sequence of pAPEC-O2-ColV also contained an intact F-like transfer region and a 45-kb region of novel DNA encoding a number of hypothetical proteins. pAPEC-O2-ColV possesses two plasmid replicons, RepFIB and RepFIIA, as reported elsewhere previously (1). In addition to encoding ColV production, the plasmid also contains an immunity gene towards the bacteriocin ColE2. This plasmid also possesses five copies of the insertion sequence IS1 and two copies of IS2, which likely play an important role in the plasmid's evolution. Overall, this 180-kb ColV plasmid is a mosaic of virulence genes, novel genes, transfer genes, and mobile genetic elements. Further work is needed to determine the roles that certain components of this plasmid have in APEC virulence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Soren Schubert from the Max von Pettenkofer Institut and Shelley Payne from the University of Texas for providing control strains for these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrozic, J., A. Ostroversnik, M. Starcic, I. Kuhar, M. Grabnar, and D. Zgur-Bertok. 1998. Escherichia coli ColV plasmid pRK100: genetic organization, stability and conjugal transfer. Microbiology 144:343-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binns, M. M., D. L. Davies, and K. G. Hardy. 1979. Cloned fragments of the plasmid ColV,I-K94 specifying virulence and serum resistance. Nature 279:778-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buell, C. R., V. Joardar, M. Lindeberg, J. Selengut, I. T. Paulsen, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, R. T. Deboy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, S. Daugherty, L. Brinkac, M. J. Beanan, D. H. Haft, W. C. Nelson, T. Davidsen, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, J. Liu, Q. Yuan, H. Khouri, N. Fedorova, B. Tran, D. Russell, K. Berry, T. Utterback, S. E. Van Aken, T. V. Feldblyum, M. D'Ascenzo, W. L. Deng, A. R. Ramos, J. R. Alfano, S. Cartinhour, A. K. Chatterjee, T. P. Delaney, S. G. Lazarowitz, G. B. Martin, D. J. Schneider, X. Tang, C. L. Bender, O. White, C. M. Fraser, and A. Collmer. 2003. The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:10181-10186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crosa, J. H., A. R. Mey, and S. M. Payne (ed.). 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 6.de Lorenzo, V., and J. B. Neilands. 1986. Characterization of iucA and iucC genes of the aerobactin system of plasmid ColV-K30 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 167:350-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dho-Moulin, M., and J. M. Fairbrother. 1999. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Vet. Res. 30:299-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobrindt, U., G. Blum-Oehler, G. Nagy, G. Schneider, A. Johann, G. Gottschalk, and J. Hacker. 2002. Genetic structure and distribution of four pathogenicity islands (PAI I536 to PAI IV536) of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect. Immun. 70:6365-6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doetkott, D. M., L. K. Nolan, C. W. Giddings, and D. L. Berryhill. 1996. Large plasmids of avian Escherichia coli isolates. Avian Dis. 40:927-930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dozois, C. M., M. Dho-Moulin, A. Bree, J. M. Fairbrother, C. Desautels, and R. Curtiss III. 2000. Relationship between the tsh autotransporter and pathogenicity of avian Escherichia coli and localization and analysis of the tsh genetic region. Infect. Immun. 68:4145-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dozois, C. M., F. Daigle, and R. Curtiss III. 2003. Identification of pathogen-specific and conserved genes expressed in vivo by an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:247-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewers, C., T. Janssen, S. Kiessling, H. C. Philipp, and L. H. Wieler. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) isolated from colisepticemia in poultry. Vet. Microbiol. 104:91-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs, P. E., J. J. Maurer, L. K. Nolan, and R. E. Wooley. 2003. Prediction of chicken embryo lethality with the avian Escherichia coli traits complement resistance, colicin V production, and presence of the increased serum survival gene cluster (iss). Avian Dis. 47:370-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilson, L., H. K. Mahanty, and R. Kolter. 1987. Four plasmid genes are required for colicin V synthesis, export, and immunity. J. Bacteriol. 169:2466-2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginns, C. A., M. L. Benham, L. M. Adams, K. G. Whithear, K. A. Bettelheim, B. S. Crabb, and G. F. Browning. 2000. Colonization of the respiratory tract by a virulent strain of avian Escherichia coli requires carriage of a conjugative plasmid. Infect. Immun. 68:1535-1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hantke, K., G. Nicholson, W. Rabsch, and G. Winkelmann. 2003. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:3677-3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heidelberg, J. F., I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, E. J. Gaidos, W. C. Nelson, T. D. Read, J. A. Eisen, R. Seshadri, N. Ward, B. Methe, R. A. Clayton, T. Meyer, A. Tsapin, J. Scott, M. Beanan, L. Brinkac, S. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, D. H. Haft, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, A. M. Wolf, J. Vamathevan, J. Weidman, M. Impraim, K. Lee, K. Berry, C. Lee, J. Mueller, H. Khouri, J. Gill, T. R. Utterback, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, K. H. Nealson, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:1118-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horne, S. M., S. J. Pfaff-McDonough, C. W. Giddings, and L. K. Nolan. 2000. Cloning and sequencing of the iss gene from a virulent avian Escherichia coli. Avian Dis. 44:179-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ike, K., K. Kawahara, H. Danbara, and K. Kume. 1992. Serum resistance and aerobactin iron uptake in avian Escherichia coli mediated by conjugative 100-megadalton plasmid. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 54:1091-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janakiraman, A., and J. M. Slauch. 2000. The putative iron transport system SitABCD encoded on SPI1 is required for full virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1146-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janben, T., C. Schwarz, P. Preikschat, M. Voss, H. C. Philipp, and L. H. Wieler. 2001. Virulence-associated genes in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) isolated from internal organs of poultry having died from colibacillosis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, J. R., and J. J. Brown. 1996. A novel multiply primed polymerase chain reaction assay for identification of variant papG genes encoding the Gal(alpha 1-4)Gal-binding PapG adhesins of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 173:920-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, T. J., C. W. Giddings, S. M. Horne, P. S. Gibbs, R. E. Wooley, J. Skyberg, P. Olah, R. Kercher, J. S. Sherwood, S. L. Foley, and L. K. Nolan. 2002. Location of increased serum survival gene and selected virulence traits on a conjugative R plasmid in an avian Escherichia coli isolate. Avian Dis. 46:342-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, T. J., J. Skyberg, and L. K. Nolan. 2004. Multiple antimicrobial resistance region of a putative virulence plasmid from an Escherichia coli isolate incriminated in avian colibacillosis. Avian Dis. 48:351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, T. J., K. E. Siek, S. J. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2005. DNA sequence and comparative genomics of pAPEC-O2-R, an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli transmissible R plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4681-4688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahn, P. L. Isolation of high-frequency recombining strains from Escherichia coli containing the V colicinogenic factor. J. Bacteriol. 96:205-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lawley, T. D., W. A. Klimke, M. J. Gubbins, and L. S. Frost. 2003. F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 224:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, G., C. Laturnus, C. Ewers, and L. H. Wieler. 2005. Identification of genes required for avian Escherichia coli septicemia by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 73:2818-2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh, S., R. Skurray, J. Celerier, M. Bagdasarian, A. Bailone, and R. Devoret. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the psiA (plasmid SOS inhibition) gene located on the leading region of plasmids F and R6-5. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss, J. E., T. J. Cardozo, A. Zychlinsky, and E. A. Groisman. 1999. The selC-associated SHI-2 pathogenicity island of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 33:74-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nolan, L. K., S. M. Horne, C. W. Giddings, S. L. Foley, T. J. Johnson, A. M. Lynne, and J. Skyberg. 2003. Resistance to serum complement, iss, and virulence of avian Escherichia coli. Vet. Res. Commun. 27:101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oelschlaeger, T. A., U. Dobrindt, and J. Hacker. 2002. Pathogenicity islands of uropathogenic E. coli and the evolution of virulence. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 19:517-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaff-McDonough, S. J., S. M. Horne, C. W. Giddings, J. O. Ebert, C. Doetkott, M. H. Smith, and L. K. Nolan. 2000. Complement resistance-related traits among Escherichia coli isolates from apparently healthy birds and birds with colibacillosis. Avian Dis. 44:23-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Provence, D. L., and R. Curtiss III. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a gene involved in hemagglutination by an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect. Immun. 62:1369-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purdy, G. E., and S. M. Payne. 2001. The SHI-3 iron transport island of Shigella boydii 0-1392 carries the genes for aerobactin synthesis and transport. J. Bacteriol. 183:4176-4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quackenbush, R. L., and S. Falkow. 1979. Relationship between colicin V activity and virulence in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 24:562-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Siek, K. E., C. W. Giddings, C. Doetkott, T. J. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2005. Characterizing the APEC pathotype. Vet. Res. 36:241-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Siek, K. E., C. W. Giddings, C. Doetkott, T. J. Johnson, M. K. Fakhr, and L. K. Nolan. 2005. Comparison of Escherichia coli isolates implicated in human urinary tract infection and avian colibacillosis. Microbiology 151:2097-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russo, T. A., and J. R. Johnson. 2000. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1753-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Sanderson, K. E., and D. R. Zeigler. 1991. Storing, shipping, and maintaining records on bacterial strains. Methods Enzymol. 204:248-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saul, D., A. J. Spiers, J. McAnulty, M. G. Gibbs, P. L. Bergquist, and D. F. Hill. 1989. Nucleotide sequence and replication characteristics of RepFIB, a basic replicon of IncF plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 171:2697-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schouler, C., F. Koffmann, C. Amory, S. Leroy-Setrin, and M. Moulin-Schouleur. 2004. Genomic subtraction for the identification of putative new virulence factors of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain of O2 serogroup. Microbiology 150:2973-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skyberg, J., S. M. Horne, C. W. Giddings, R. E. Wooley, P. S. Gibbs, and L. K. Nolan. 2003. Characterizing avian Escherichia coli isolates with multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Avian Dis. 47:1441-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith, H. W., and M. B. Huggins. 1980. The association of the O18, K1 and H7 antigens and the ColV plasmid of a strain of Escherichia coli with its virulence and immunogenicity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 121:387-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snedecor, G. W., and W. G. Cochran. 1980. Statistical methods, 7th ed. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa.

- 47.Sorsa, L. J., S. Dufke, J. Heesemann, and S. Schubert. 2003. Characterization of an iroBCDEN gene cluster on a transmissible plasmid of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: evidence for horizontal transfer of a chromosomal virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 71:3285-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tettelin, H., D. Radune, S. Kasif, H. Khouri, and S. L. Salzberg. 1999. Optimized multiplex PCR: efficiently closing a whole-genome shotgun sequencing project. Genomics 62:500-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tivendale, K. A., J. L. Allen, C. A. Ginns, B. S. Crabb, and G. F. Browning. 2004. Association of iss and iucA, but not tsh, with plasmid-mediated virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 72:6554-6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vandekerchove, D., F. Vandemaele, C. Adriaensen, M. Zaleska, J. P. Hernalsteens, L. D. Baets, P. Butaye, F. V. Immerseel, P. Wattiau, H. Laevens, J. Mast, B. Goddeeris, and F. Pasmans. 2005. Virulence-associated traits in avian Escherichia coli: comparison between isolates from colibacillosis-affected and clinically healthy layer flocks. Vet. Microbiol. 108:75-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vidotto, M. C., J. M. Cacao, C. R. Goes, and D. S. Santos. 1991. Plasmid coding for aerobactin production and drug resistance is involved in virulence of Escherichia coli avian strains. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 24:677-685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, Z., and T. G. Rossman. 1994. Large-scale supercoiled plasmid preparation by acidic phenol extraction. BioTechniques 16:460-463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waters, V. L., and J. H. Crosa. 1991. Colicin V virulence plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 55:437-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S. R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wooley, R. E., P. S. Gibbs, T. P. Brown, J. R. Glisson, W. L. Steffens, and J. J. Maurer. 1998. Colonization of the chicken trachea by an avirulent avian Escherichia coli transformed with plasmid pHK11. Avian Dis. 42:194-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wooley, R. E., L. K. Nolan, J. Brown, P. S. Gibbs, C. W. Giddings, and K. S. Turner. 1993. Association of K-1 capsule, smooth lipopolysaccharides, traT gene, and colicin V production with complement resistance and virulence of avian Escherichia coli. Avian Dis. 37:1092-1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou, D., W. D. Hardt, and J. E. Galan. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium encodes a putative iron transport system within the centisome 63 pathogenicity island. Infect. Immun. 67:1974-1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]