Abstract

The hemF gene of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 is predicted to code for an oxygen-dependent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase. We found that a HemF− mutant strain is unable to grow under aerobic conditions. We also determined that hemF expression is controlled by oxygen, which is mediated, at least in part, by the response regulatory protein PrrA.

The α-Proteobacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 can obtain energy by photosynthesis as well as by aerobic and anaerobic respiration, which are supported by its ability to synthesize both heme and bacteriochlorophyll. In this organism, both of these compounds are derived from 5-aminolevulinic acid (reviewed in reference 10), and directing the flow of intermediates towards one or the other tetrapyrrole involves transcriptional regulation of genes coding for several enzymes in the branching biosynthesis pathway (15, 18, 27, 29). Here, we report that the hemF gene of R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, coding for a putative oxygen-dependent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, is also regulated at the level of transcription.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Culturing of the bacteria was performed as described previously (4, 6, 22, 24). The hemF gene (527 bp upstream of the translation initiation site to 91 bp downstream of the nonsense codon TGA) was amplified from total genomic DNA with the following primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA): HemF-UP, 5′-GTCACTTCGTCTCGGGATAGGTCGCGCGGCACTG-3′; HemF-DOWN, 5′-CCTCGCATGAGAGCGTGAGCAAGCGTCAGAGGCC-3′. The 1,496-bp product was cloned into the MscI site of pUI1087 (30), generating pKS7. DNA sequence analysis of both strands confirmed the integrity of the cloned sequences. Construction of the suicide vector pKS13, used to deliver the defective ΔhemF::ΩSpr-Str allele to R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, began with moving the hemF sequences contained on an EcoRI-XbaI DNA fragment from pKS7 into pBBR1MCS2 (12), creating pKS9. A 361-bp BamHI DNA fragment was deleted from pKS9 (which deletes 44 bp upstream of the HemF coding sequences through sequences coding for amino acid residues 1 to 105), and an omega Sp-St resistance cassette (20) was inserted at the remaining unique BamHI site. From this plasmid, pKS11, a 3,135-bp SmaI fragment containing ΔhemF::ΩSpr-Str was moved into pSUP202 (23), replacing the vector sequences contained on a 1,348-bp ScaI fragment and creating pKS13. The hemF::lacZ transcription reporter plasmid pJZ84 was constructed by first inserting a 717-bp SmaI-NcoI DNA fragment from pKS9, which includes 471 bp of hemF sequence upstream of the translation initiation site, into pUI1087 (30), and then, using the flanking PstI-XbaI vector restriction sites, the hemF sequences were positioned and correctly oriented in front of a promoterless lacZ gene in plasmid vector pCF1010 (14).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | ||

| 2.4.1 | Wild type | W. Sistrom |

| JZ3534 | ΔhemF::Ω(Spr-Str) | This study |

| PRRA2 | ΔprrA::Ω(Spr-Str) | 7 |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5αphe | DH5αphe::Tn10dCmr | 8 |

| HB101 | F− Δ(gtp-proA)62 leuB6 supE44 ara-14 galK2 lacY1 | 1 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS2 | Kmr | 12 |

| pBSIISK+ | Apr | Stratagene |

| pCF1010 | Promoterless lacZ vector, Mob+ Tcr Spr-Str | 14 |

| pJZ84 | hemF::lacZ transcription fusion in pCF1010 | This study |

| pKS7 | hemF in pUI1087 | This study |

| pKS9 | hemF in pBBR1MCS2 | This study |

| pKS11 | Ω(Spr-Str) inserted into (ΔBamHI)pKS9 | This study |

| pKS13 | ΔhemF::Ω(Spr-Str) in pSUP202 | This study |

| pRK2013 | ColEI replicon, Tra+ of RK2, Kmr | 5 |

| pSUP202 | pBR325 derivative, Mob+ Apr Cmr Tcr | 23 |

| pUI1087 | pBSIISK+ with modified polylinker | 30 |

| pUI1638 | Source of Ω(Spr-Str) cassette | 8 |

The hemF gene is required for aerobic growth.

Using plasmid pKS13, we were unable to obtain HemF− mutants under aerobic conditions, but suitable mutant candidates were obtained when plates of exconjugants were incubated under anaerobic growth conditions (in the dark on medium containing dimethyl sulfoxide as an alternate electron acceptor). Among them, mutant strain JZ3534 was confirmed to be structurally correct by Southern hybridization (results not shown). We also found that moving plasmid pKS9, containing an intact hemF gene, into mutant strain JZ3534 restored growth under aerobic conditions to rates comparable to those of the wild-type strain 2.4.1.

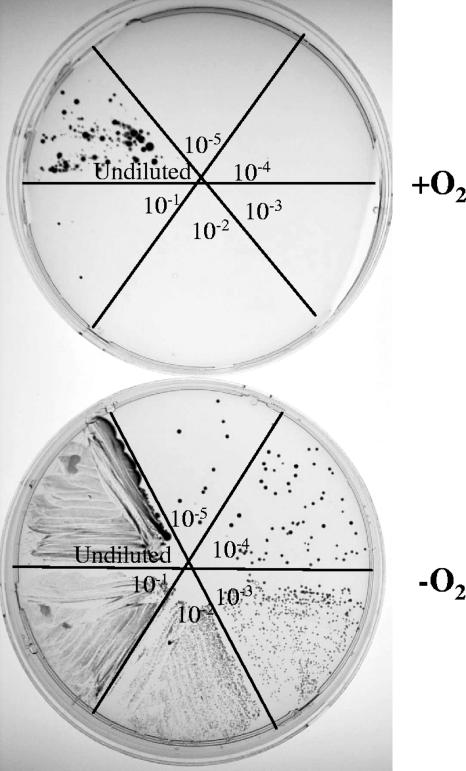

We further evaluated the requirement for an intact hemF gene for aerobic growth by first culturing mutant strain JZ3534 under anaerobic conditions and then spreading serial dilutions of the culture on two plates, one of which was incubated aerobically and the other anaerobically. Growth after 5 days on the two plates is shown in Fig. 1, and as listed in Table 2, we found the numbers of CFU differed by approximately 5 orders of magnitude. This suggested that those few colonies that formed on the aerobically incubated plate were from cells containing a second mutation that suppresses the growth defect conferred by the absence of a functional hemF gene. To explore this possibility we sparged liquid cultures, inoculated from the anaerobically grown preculture, with low oxygen (2%) and with air (approximately 21% oxygen). The results, listed in Table 2, revealed that the aerobic versus anaerobic viable cell counts of the low-oxygen culture differed by approximately 5 orders of magnitude, but the counts of the culture that had been sparged with air differed by only approximately 10-fold. Finally, we performed a comparative (aerobic versus anaerobic) viable cell count of four isolated colonies from the air-sparged culture that had formed on the aerobically incubated plate. Now the numbers of CFU were of the same order of magnitude on both sets of plates, each being 1 × 107 to 4 × 107 CFU/ml. Apparently, whereas low or no oxygen permits growth of the HemF− mutant strain in liquid culture, high concentrations of oxygen are nonpermissive and suppressor mutations are selected for.

FIG. 1.

Plates of serial dilutions from an anaerobic culture of HemF− mutant strain JZ3534 (see Table 1). The plates spread with 10-μl samples of 10-fold serial dilutions were incubated under the conditions shown.

TABLE 2.

Viable cell counts of cultures of R. sphaeroides mutant strain JZ3534 grown under different conditions

| Culture conditiona | Counts of CFU/ml following culturing on plates

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic incubation | Anaerobic incubationb | |

| Anaerobic | 2 × 103 | 9 × 107 |

| 2% Oxygen | 2 × 103 | 1.7 × 108 |

| 21% Oxygen | 1 × 106 | 3.5 × 107 |

Refers to the culture conditions used prior to plating and counting the colonies.

Plates were incubated anaerobically in the dark, and dimethyl sulfoxide was added to the medium as an alternate electron acceptor.

Oxygen controls hemF expression.

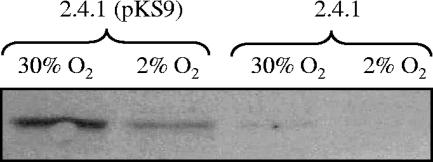

Using methods previously described (9), immunoblots prepared from extracts of wild-type 2.4.1 cells with and without pKS9 carrying the hemF gene, grown either aerobically or anaerobically, were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-HemF antisera (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc., Reamstown, PA). As shown in Fig. 2, the levels of HemF protein detected were much higher in cells grown aerobically than in anaerobically grown cells, and the amount correlated with gene dosage. These results suggest that hemF expression is controlled by oxygen.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblots of protein samples probed with anti-HemF antiserum. Samples examined are identified in the figure and are derived from cells grown under the designated conditions. In all cases, equivalent amounts of total protein were used (25 μg).

Transcription of hemF is regulated by PrrA.

In R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, established regulators of gene expression that respond to changes in oxygen tensions include FnrL, the AppA-PpsR regulatory system, and the PrrBA two-component system (reviewed in reference 28). While all genes known to be regulated by FnrL have an easily discernible FNR consensus-like sequence within their upstream sequences (16-18, 27, 29, 31), hemF does not, making it unlikely that FnrL regulates hemF transcription. Also, transcriptome profiling demonstrated that hemF is not a member of the PpsR regulon (15). Putative DNA binding sites of the response regulatory protein PrrA are difficult to identify by DNA sequence inspection alone, as there is low conservation of the recognition elements and because the distance between half sites is variable (13). Therefore, we evaluated the role of PrrA in hemF expression using the hemF::lacZ transcriptional reporter plasmid pJZ84 (Table 1). β-Galactosidase activities in extracts of wild-type 2.4.1 versus PrrA− mutant strain PRRA2 cells having the reporter plasmid were assayed according to previously described methods (9). As indicated in Table 3, enzyme activity levels are approximately threefold lower in extracts of anaerobically versus aerobically grown wild-type 2.4.1 cells. By contrast, we found β-galactosidase activity levels are approximately 1.6-fold higher in extracts of anaerobically cultured PRRA2 mutant cells than in extracts of cells grown aerobically.

TABLE 3.

β-Galactosidase activities in cell extracts of R. sphaeroides bearing the hemF::lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid pJZ84

| Strain | β-Galactosidase activitya

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% oxygen

|

Anaerobic

|

|||

|

σn |  |

σn | |

| Wild type 2.4.1(pJZ84) | 908 | 27 | 296 | 7 |

| PRRA2(pJZ84) | 510 | 11 | 795 | 13 |

Activities are expressed in units of β-galactosidase activity, defined as micromoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein extract. Values with means ( ) and standard deviations (σn) indicated are from duplicate assays of activities in extracts from three independent isolates. The strains were grown in Sistrom's minimal succinate (24) with tetracycline (final concentration, 0.8 μg ml−1) either aerobically; by sparging liquid cultures with a mixture of 30% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide, and 65% nitrogen; or anaerobically in the dark with dimethyl sulfoxide as alternate electron acceptor.

) and standard deviations (σn) indicated are from duplicate assays of activities in extracts from three independent isolates. The strains were grown in Sistrom's minimal succinate (24) with tetracycline (final concentration, 0.8 μg ml−1) either aerobically; by sparging liquid cultures with a mixture of 30% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide, and 65% nitrogen; or anaerobically in the dark with dimethyl sulfoxide as alternate electron acceptor.

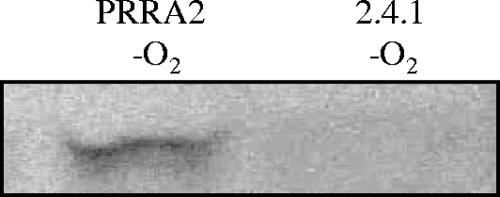

We also probed membranes of total protein from anaerobically grown wild-type 2.4.1 and PRRA2 mutant cells with anti-HemF antiserum. As shown in Fig. 3, while no HemF protein could be detected in the wild-type 2.4.1 lysate, it is clearly discernible in the lysate of the PrrA− mutant cells.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblots of protein samples probed with anti-HemF antiserum. Samples examined are from cultures of R. sphaeroides wild-type strain 2.4.1 or mutant strain PRRA2 cells grown in parallel under anaerobic dark (with dimethyl sulfoxide) conditions. Equivalent amounts of total protein were used (53 μg).

Conclusions.

Based on our results, we conclude that the hemF gene of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 is required for colony formation in the presence of air or for growth of liquid cultures sparged with air. These phenotypes are consistent with the hemF expression pattern we discerned at the protein level using immunoblot analysis; namely, HemF levels are reduced in cells grown under anaerobic conditions compared to levels present in aerobically grown cells.

Our measurements of transcription using a hemF::lacZ reporter plasmid indicate that hemF is regulated at the level of transcription, which is consistent with transcript measurements reported by Moskvin et al. (15). We also found that downregulation of hemF when oxygen tensions are reduced requires an intact prrA gene. A recent description of PrrA regulation in R. sphaeroides indicates that although PrrA positively affects transcription for many genes belonging to its regulon, it can also function as a negative effector of transcription (11). Based on our results, this is true for the hemF gene. The data also suggest there may be further complexities associated with regulated expression of hemF, since β-galactosidase activities measured in extracts of cells grown aerobically differ by approximately 56% in the PrrA− strain PRRA2 versus wild-type 2.4.1.

Panek and O'Brian (19) found that, unlike hemN genes, which code for enzymes that catalyze oxygen-independent formation of protoporphyrinogen IX, hemF genes are not widely represented among bacteria. Further, all bacteria having hemF genes also have hemN genes. For several species of bacteria that have hemF, the hemN gene alone is capable of meeting the cellular needs for protoporphyrinogen IX regardless of the presence or absence of oxygen (21, 25, 26), and measurements of hemN and hemF transcript levels in E. coli K-12 indicate that those genes are not greatly affected by varying oxygen tensions (3). By contrast, in R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, transcription of hemN and hemZ, coding for putative oxygen-independent isoenzymes (2, 29), are induced by lowering oxygen tensions in an FnrL-dependent manner (18, 27). Now we have found that hemF expression is low in the presence of low or no oxygen and high when oxygen tensions are high. We suggest that, for R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, oxygen availability not only dictates what catalytic mechanism can be used for protoporphyrinogen IX formation but also which enzyme type is present in concentrations that are sufficient to support growth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by GR-172 from the Michigan Life Sciences fund and award no. 0320550 from the National Science Foundation.

We acknowledge the outstanding technical support for a portion of these studies that was provided by L. Schovan, and we thank S. Kaplan and J. Eraso for providing R. sphaeroides mutant strain PRRA2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coomber, S. A., R. M. Jones, P. M. Jordan, and C. N. Hunter. 1992. A putative anaerobic coproporphyrinogen III oxidase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. I. Molecular cloning, transposon mutagenesis and sequence analysis of the gene. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3159-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covert, M., E. Knight, J. Reed, M. Herrgard, and B. Palsson. 2004. Integrating high-throughput and computational data elucidates bacterial networks. Nature 429:92-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis, J., T. J. Donohue, and S. Kaplan. 1988. Construction, characterization, and complementation of a Puf− mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 170:320-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ditta, G., S. Stanfield, D. Corbin, and D. Helinski. 1980. Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:7347-7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donohue, T. J., A. G. McEwan, and S. Kaplan. 1986. Cloning, DNA sequence, and expression of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene. J. Bacteriol. 168:962-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eraso, J., and S. Kaplan. 1996. Complex regulatory activities associated with the histidine kinase PrrB in expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 178:7037-7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1994. prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation in photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 176:32-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fales, L., L. Kryszak, and J. Zeilstra-Ryalls. 2001. Control of hemA expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: effect of a transposon insertion in the hbdA gene. J. Bacteriol. 183:1568-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan, P. (ed.). 1991. Biosynthesis of tetrapyrroles. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 11.Kaplan, S., J. Eraso, and J. Roh. 2005. Interacting regulatory networks in the facultative photosynthetic bacterium, Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovach, M., R. Phillips, P. Elzer, R. Roop, Jr., and K. Peterson. 1994. pBBR1MCS: A broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques 16:800-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laguri, C., M. Phillips-Jones, and M. Williamson. 2003. Solution structure and DNA binding of the effector domain from the global regulator PrrA (RegA) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides: insights into DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6778-6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, J., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Transcriptional regulation of puc operon expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Analysis of the cis-acting downstream regulatory sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 270:20453-20458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moskvin, O., L. Gomelsky, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. Transcriptome analysis of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides PpsR regulon: PpsR as a master regulator of photosystem development. J. Bacteriol. 187:2148-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mouncey, N. J., and S. Kaplan. 1998. Cascade regulation of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase (dor) gene expression in the facultative phototroph Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T. J. Bacteriol. 180:2924-2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mouncey, N. J., and S. Kaplan. 1998. Oxygen regulation of the ccoN gene encoding a component of the cbb3 oxidase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T: involvement of the FnrL protein. J. Bacteriol. 180:2228-2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh, J.-I., J. Eraso, and S. Kaplan. 2000. Interacting regulatory circuits involved in orderly control of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 182:3081-3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panek, H., and M. O'Brian. 2002. A whole genome view of prokarotic haem biosynthesis. Microbiology 148:2273-2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prentki, P., and H. M. Krisch. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rompf, A., C. Hungerer, T. Hoffmann, M. Lindenmeyer, U. Romling, U. Gross, M. Doss, H. Aria, Y. Igarashi, and D. Jahn. 1998. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemN by the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol. Microbiol. 29:985-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook, J., E. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1985. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:37-45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sistrom, W. R. 1960. A requirement for sodium in the growth of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Gen. Microbiol. 22:778-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troup, B., C. Hungerer, and D. Jahn. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the Escherichia coli hemN gene encoding the oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase. J. Bacteriol. 177:3326-3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu, K., J. Delling, and T. Elliott. 1992. The genes required for heme synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium include those encoding alternative functions for aerobic and anaerobic coproporphyrinogen oxidation. J. Bacteriol. 174:3953-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeliseev, A., and S. Kaplan. 1999. A novel mechanism for the regulation of photosynthesis gene expression by the TspO outer membrane protein of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Biol. Chem. 274:21234-21243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeilstra-Ryalls, J., and S. Kaplan. 2004. Oxygen intervention in the regulation of gene expression: the photosynthetic bacterial paradigm. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61:417-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeilstra-Ryalls, J. H., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Aerobic and anaerobic regulation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: the role of the fnrL gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:6422-6431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeilstra-Ryalls, J. H., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Regulation of 5-aminolevulinic acid synthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: the genetic basis of mutant H-5 auxotrophy. J. Bacteriol. 177:2760-2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeilstra-Ryalls, J. H., and S. Kaplan. 1998. Role of the fnrL gene in photosystem gene expression and photosynthetic growth of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 180:1496-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]