Abstract

The process of sporulation in the bacterium Bacillus subtilis is known to involve the programmed activation of several hundred protein-coding genes. Here we report the discovery of previously unrecognized genes under sporulation control that specify small, non-protein-coding RNAs (sRNAs). Genes for sRNAs were identified by transcriptional profiling with a microarray bearing probes for intergenic regions in the genome and by use of a comparative genomics algorithm that predicts regions of conserved RNA secondary structure. The gene for one such sRNA, SurA, which is located in the region between yndK and yndL, was induced at the start of development under the indirect control of the master regulator for entry into sporulation, Spo0A. The gene for a second sRNA, SurC, located in the region between dnaJ and dnaK, was switched on at a late stage of sporulation by the RNA polymerase sigma factor σK, which directs gene transcription in the mother cell compartment of the developing sporangium. Finally, a third intergenic region, that between polC and ylxS, which specified several sRNAs, including two transcripts produced under the control of the forespore-specific sigma factor σG and a third transcript generated by σK, was identified. Our results indicate that the full repertoire of sporulation-specific gene expression involves the activation of multiple genes for small, noncoding RNAs.

Protein-coding genes are the traditional focus of interest in microbial genetics, but increasing evidence points to the importance of genes that specify small, untranslated RNAs (sRNAs) (40). sRNAs range in size from approximately 30 nucleotides (nt) to 600 nt in bacteria, and in a growing number of cases functions have been elucidated for specific sRNAs. For example, in Escherichia coli, where sRNAs have been studied most extensively, functions have been reported for 15 of the approximately 80 sRNAs so far identified (12, 19). Among these are 6S RNA, which binds to and inhibits RNA polymerase containing σ70 and was found to play a role in long-term cell survival (42); OxyS, which is induced under oxidative stress and regulates the expression of at least 40 genes, including the mRNAs for the transcriptional regulator FhlA and the stationary-phase sigma factor σS (1, 2); DsrA, which enhances the translation of the mRNA for σS and inhibits the translation of the mRNA for the global repressor H-NS (22, 38); and finally, RyhB, which targets mRNAs for proteins involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and iron storage and the mRNA for superoxide dismutase (28, 29). sRNAs have been detected in other bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus (18), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (45), Vibrio cholerae (7, 24), and Borrelia burgdorferi (32).

sRNAs have also been reported for the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus subtilis, the subject of this report. Examples of sRNA that are similar to small, untranslated RNAs found in non-spore-forming genera are SsrA (21), small cytoplasmic RNA (31), P RNA (26), two 6S-like RNAs called 6S-1 and 6S-2 (3, 5, 41-43), and a 5S-like RNA (11). A recent example of an sRNA that is unique to B. subtilis is RatA, an antisense RNA for the mRNA for the peptide toxin TxpA (37).

In light of these examples, we wondered whether sRNAs are a feature of complex pathways of gene control, such as sporulation in B. subtilis. Sporulation is governed by a cascade of transcriptional regulatory proteins (27). The master regulator for entry into sporulation is the response regulator Spo0A. Shortly after the start of sporulation, the developing cell is divided into compartments called the forespore and the mother cell. Gene expression in the forespore is principally controlled by the successive appearance of the alternative sigma factors σF and σG. Meanwhile, gene expression in the mother cell is governed in a somewhat more complex manner by a hierarchical regulatory cascade involving the appearance in alternating order of two alternative sigma factors, σE and σK, and two DNA-binding proteins, SpoIIID and GerE. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling experiments have identified over 500 protein-coding genes that are activated over the course of sporulation, and much progress has been made in assigning individual genes to the direct control of one or another of the aforementioned regulatory proteins (10, 30).

These transcriptional profiling experiments were carried out with microarrays embedded with probes for the annotated protein-coding genes in the B. subtilis genome. To search for additional genes under sporulation control that could specify sRNAs, we took two complementary approaches, one involving a microarray designed to detect transcripts arising from intergenic regions of the genome (that is, from in between annotated protein-coding sequences) (23) and the other a comparative genomics approach involving the prediction of RNAs with conserved secondary structures (34). The combined approaches led to the identification of three intergenic regions containing sequences for several small, apparently untranslated RNAs produced during sporulation and under the direct or indirect control of three sporulation regulatory proteins. We speculate that sporulation-controlled genes for many additional sRNAs are waiting to be discovered and that the full repertoire of sporulation gene expression may be more complex than previously appreciated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Affymetrix arrays.

All Affymetrix array data were obtained from previously published experiments (23). Probe sets specific to both strands of 603 intergenic (“gap”) regions larger than 250 nucleotides were represented on an “antisense” oligonucleotide array complementary to the Bacillus subtilis genome. The array was custom designed by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) using a published DNA sequence (GenBank accession no. NC_000964). A general description of Affymetrix GeneChip microarrays has been previously reported (8, 9, 25).

Growth conditions.

Strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani, Difco sporulation (DS) medium (36), or hydrolyzed casein growth medium and induced to sporulate by resuspension in Sterlini-Mandelstam medium (15, 39). Ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (5 μg ml−1), tetracycline (10 μg ml−1), spectinomycin (100 μg ml−1), and MLS (1 μg ml−1 erythromycin and 25 μg ml−1 lincomycin) were added to agar plates where appropriate.

Plasmid and strain construction.

Strains and plasmids used for this study are listed in Table 1. Standard techniques were used for stain construction (15). All plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α using standard methods. All PCR products were amplified from chromosomal DNA from strain PY79. Primers used for the generation of PCR products indicated below are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All transformations with cells of B. subtilis were carried out by the two-step transformation procedure (15).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference, source, or construction |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis strains | ||

| PY79 | Wild type; prototrophic | 46 |

| JS88 | surAΔ::spc | This study |

| JS99 | amyE::PsurA-lacZ (cat) | pJS9→PY79 |

| JS101 | amyE::PsurA-lacZ (cat) spo0A::spc | RL2242→JS99 |

| JS103 | amyE::PsurA-lacZ (cat) spo0H::kan | RL2201→JS99 |

| JS107 | amyE::PsurA-lacZ (cat) abrB::erm | RL620→JS99 |

| JS108 | amyE::PsurA-lacZ (cat) abrB::erm spo0A::spc | RL2242→JS107 |

| JS109 | amyE::PyndL-lacZ (cat) | pJS14→PY79 |

| JS113 | surAΔ::spc | This study |

| JS115 | amyE::PsurA-lacZ (cat) spo0H::kan abrB::erm | RL620→JS103 |

| JS122 | amyE::PyndL-lacZ (cat) spoIVCAΔ::erm | RL33→JS109 |

| JS123 | yndLΔ::tet | This study |

| CR1 | polC-ylxS-IGRΔ::spc | This study |

| RL33 | [JH642] spoIVCAΔ::erm trpC2 pheAI | Laboratory stock |

| RL560 | spoIIIG::cat | Laboratory stock |

| RL620 | abrBΔ::erm | Laboratory stock |

| RL1061 | spoIIGB::erm | Laboratory stock |

| RL1275 | spoIIAC::erm | Laboratory stock |

| RL2201 | spo0HΔ::kan | Laboratory stock |

| RL2242 | spo0AΔ::spc | Laboratory stock |

| RL3217 | gerEΔ::cat | Laboratory stock |

| RL3218 | gerEΔ::cat spoIVCBΔ::erm | Laboratory stock |

| RL3230 | spoIVCA::erm | Laboratory stock |

| E. coli strain DH5α | Cloning host | Laboratory stock |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDG1661 | Permits transcriptional fusion to lacZ (cat) | 13 |

| pDG1514 | Contains tet antibiotic cassette | 14 |

| pDG1727 | Contains spc antibiotic cassette | 14 |

| pGEM-3Zf(+) | Permits in vitro transcription from SP6 and T7 RNA polymerase promoters (amp) | Promega |

| pBSIIKS(+) | Cloning vector (amp) | Stratagene |

| pJS9 | pDG1661 with surA | This study |

| pJS14 | pDG1661 with yndL | This study |

| pJS50 | pGEM-3Zf(+) with polC-ylxS IGR | This study |

| pJS72 | pBSIIKS(+) with surC and upstream sequence for dideoxy sequencing | This study |

| pCR1 | pBSIIKS(+) with polC-ylxS IGR and upstream sequence for dideoxy sequencing | This study |

To generate the lacZ transcriptional fusion for the SurA promoter (pJS9), a PCR fragment containing the start site and upstream DNA sequence was amplified with oligonucleotide primers oJS229 and oJS230, ligated to the HindIII/BamHI sites of pDG1661, and transformed into PY79 to create JS99. To observe the transcriptional activity of PsurA-lacZ in various null mutant backgrounds, competent JS99 cells were subsequently transformed with chromosomal DNA from a Δspo0A strain (RL2242) to create JS101, a Δspo0H strain (RL2201) to create JS103, a ΔabrB strain (RL620) to create JS107, a Δspo0A ΔabrB strain to create JS108, and a Δspo0H ΔabrB strain to create JS115. A lacZ transcriptional fusion for the yndL promoter (pJS14) was generated as for SurA above using oligonucleotide primers oJS253 and oJS254 to create JS109. To observe the transcriptional activity of PyndL-lacZ in a σK null background, competent JS109 cells were transformed with chromosomal DNA from a ΔspoIVCA strain (RL3230) to create JS122.

To generate a dideoxy sequencing ladder for primer extension experiments, a PCR fragment containing the SurC intergenic region and upstream sequence was amplified with oligonucleotide primers oJS445 and oJS446 and ligated to the BamHI/PstI sites of pBSIIKS(+) to create pJS72. For dideoxy sequencing of the polC-ylxS region, a PCR fragment containing the polC-ylxS intergenic region and upstream sequence was amplified with oligonucleotide primers oCR9 and oCR10 and ligated to pBSIIKS(+) as above to create pCR1.

Deletion/insertion mutants were created by the technique of long-flanking-homology PCR (44) using the following primers: oJS154, oJS254b, oJS255, and oJS157 for ΔsurA (JS113); and oJS260, oJS261, oJS262, and oJS263 for ΔyndL (JS123). Primers and oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. pDG1514 was utilized for the tetracycline resistance cassette and pDG1727 for the spectinomycin cassette.

RNA isolation.

All RNA purifications were performed as previously described (37).

Northern blot analysis and probe labeling.

Northern blots and radioactive probe labeling were performed as previously described (37). The double-stranded PCR probes were amplified with oligonucleotides oJS74 and oJS75 for SurA, oJS321 and oJS322 for SurC, and oJS325 and oJS326 for the polC-ylxS region.

β-Galactosidase assays.

One-milliliter aliquots of each culture were grown in hydrolyzed casein growth medium, resuspended in Sterlini-Mandelstam sporulation medium (15, 39), and harvested by centrifugation at different times before and during sporulation. The cell pellets were stored at −80°C until further analysis. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as previously described (15).

Primer extension and dideoxy sequencing.

Primer extension and dideoxy sequencing experiments were performed as previously described (37). Ten to 40 μg of RNA was analyzed using the following end-labeled primers: oJS265 for yndL, oJS435 for SurC, and oCR12 for the polC-ylxS region. Plasmid templates for dideoxy sequencing were pJS17 for yndL, pJS72 for SurC, and pCR1 for the polC-ylxS region. Primers and oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

5′ and 3′ RACE PCR.

5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) assays were carried out using tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) (Epicenter Technologies) and a 5′ RNA adaptor (JSA3; Dharmacon Research) as previously described (4, 6, 37). Reverse transcription was conducted using oJS435 for SurC and oCR12 and oCR13 for the polC-ylxS region. PCR amplification was conducted using the adaptor-specific primer JS517 and the gene-specific primers oJS522 for SurC and oCR12 or oCR13 for the polC-ylxS region. Non-TAP-treated 5′ RACE was performed as described previously (10) for SurA. RNA was purified from samples collected at hour 2.5 of sporulation by the resuspension method. The primers used were oJS2 and oJS193. 3′ RACE assays were carried out as previously described using the 3′ RNA adaptor JSE1 (Dharmacon Research) (4, 6, 37). Reverse transcription was conducted with a primer complementary to the 3′ RNA adaptor sequence (JS518). PCR amplification was conducted with primer JS18 and the gene-specific primers oJS523 for SurC and oJS525 for the polC-ylxS region. Sequencing was conducted using primers M13-For and M13-Rev. Primers and oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

QRNA.

The QRNA comparative genomic program can be downloaded from http://www.genetics.wustl.edu/eddy/software. A detailed mathematical description of the program can be found in reference 34. The sequenced genomes used for comparison at the time of the study were B. subtilis strain 168 (GenBank accession no. NC_000964), Bacillus anthracis A2012 (GenBank accession no. NC_003995), Bacillus halodurans C-125 (GenBank accession no. NC_002570), Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 (GenBank accession no. NC_004722), Oceanobacillus iheyensis HTE831 (GenBank accession no. NC_004193), Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 (GenBank accession no. NC_003030), and Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e (GenBank accession no. NC_003210). All annotated intergenic sequences for B. subtilis that were ≥50 nt were compared in a pairwise fashion to the annotated intergenic sequences of the related genomes above using BLASTN (WU-BLAST version 2.2.6). The B. subtilis genome contains ∼4,100 annotated genes and ∼2,359 intergenic regions of at least 50 nt.

Standard default parameters were used for collecting QRNA alignments (P value of <0.01, length of conservation of ≥50 nt, and overall identity of ≥65%), and each alignment was analyzed as described previously (34, 35). Scanning windows of 150 nt, moving 50 nt at a time, were also utilized for some genomes to look for any further hits. Regions classified as “RNA” by the program with a log odds score of ≥5 bits were kept. Many hits were classified as “RNA/other” and contained log odds scores of <5 bits. Several of the “RNA/other” hits were further analyzed as putative structural RNAs, since the known structural RNA ssrA was also classified as “RNA/other” and reported a lower score. Hits classified as “COD” were not examined further. Once a list of putative structural RNA regions was compiled, the flanking genes for each of the intergenic regions were determined for both B. subtilis and the compared genome. All predicted regions with known RNA secondary structure, such as amino acid biosynthetic operons, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, rRNA spacers, transcriptional attenuators of ribosomal protein, riboswitch-containing genes, or other cis-regulatory RNA elements, were not pursued. The most promising “RNA” hits were considered to be those in which one or both of the flanking genes were conserved for both of the compared genomes. Table S2 in the supplemental material contains the complete list of regions predicted to contain conserved RNA secondary structure.

RNA secondary structure prediction.

Secondary structures were predicted using the Zuker Mfold program version 3.1. The prediction with the highest folding free energy value was utilized.

RESULTS

Identifying genes for sporulation-specific sRNAs.

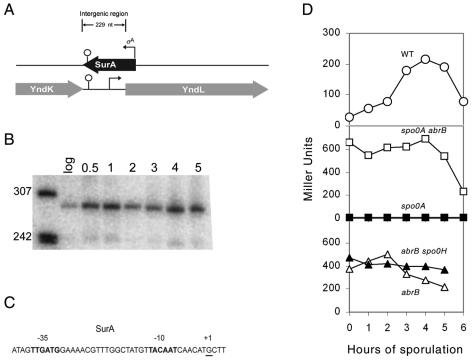

We took two complementary approaches to identifying candidate genes for sporulation-specific sRNAs. In one approach, we searched for transcripts from intergenic regions (IGRs) using an Affymetrix microarray that contained probes for many IGRs in the genome that were ≥250 bp in length (23). Northern blot analysis was then carried out using PCR-generated double-stranded DNA probes corresponding to IGRs (a total of 13) for which transcripts had been detected. In this way, nine putative sRNAs were detected, one of which is a 280-nt-long transcript from the IGR between yndK and yndL named SurA (for small, untranslated RNA A) (Fig. 1A) and which increased markedly in abundance at the start of sporulation (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Developmental regulation of SurA. (A) Orientation of SurA and flanking genes. Bent arrows indicate transcriptional start sites. The same stem-loop terminator is predicted for both the SurA and yndK sequence. The diagram is drawn to scale. (B) Northern blot of total RNA (5 μg) isolated from wild-type cells grown in DS medium at 37°C and collected during exponential growth (log) and at hour 0.5 and hours 1 to 5 of sporulation. RNAs were detected using a double-stranded PCR probe for the SurA intergenic region. The molecular weight marker was 5′-end-labeled MspI fragments of pBR322 DNA that had been denatured. (C) Depiction of the 5′ end of the SurA transcript (+1; underlined) found using 5′ RACE and the predicted upstream promoter (−10 and −35) that resembles a σA recognition sequence. (D) β-Galactosidase activity for transcriptional SurA lacZ fusions for wild-type (○) (JS99), spo0A (▪) (JS101), spo0A abrB (□) (JS108), abrB (▵) (JS107), and abrB spo0H (▴) (JS115) cells. All cultures were sporulated by the resuspension method at 37°C.

In the second approach, we used the algorithm QRNA to search for potential conserved RNA secondary structures by comparing IGRs in the B. subtilis genome with corresponding IGRs in the genomes of B. anthracis, B. halodurans, B. cereus, O. iheyensis, C. acetobutylicum, and L. monocytogenes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). We restricted the analysis to cases for which conserved RNA secondary structures were not previously known and for which the IGR was flanked by protein-coding genes that were orthologous between the species being compared. Northern blot analysis revealed candidate sRNAs in 8 of 12 cases that met these criteria. In two of the eight cases, a transcript(s) that was absent in RNA from vegetative cells but present in RNA from cells undergoing sporulation was observed. One such case was the IGR between dnaJ and dnaK, which was identified by QRNA on the basis of the predicted conservation of RNA secondary structure with that for a corresponding IGR of B. anthracis, leading to the discovery of a sporulation-controlled gene for an sRNA designated SurC (see below). The other case was the IGR between polC and ylxS, which was identified by QRNA on the basis of conservation with B. halodurans (see below).

Characterization of the gene for an sRNA from the yndK-yndL intergenic region.

We mapped the 5′ end of the 280-nt sRNA SurA by carrying out 5′ RACE and primer extension and found an apparent start site for a promoter recognized by RNA polymerase containing the housekeeping sigma factor σA (Fig. 1C). The apparent start site was located at an appropriate distance downstream of a strong match (TGTTAcAAT, representing an eight-out-of-nine match) to a canonical “extended −10” sequence (TGNTATAAT) and a partial match (TTGAtg [lowercase letters indicate nonmatching nucleotides], representing a four-out-of-six match) to a canonical “−35” sequence (TTGACA), which were separated from each other by an appropriate spacing of 17 bp (that is, between TTGAtg and the traditional hexameric −10 sequence TATAAT) (16). We verified that this was a σA-controlled promoter by runoff transcription using purified σA-containing RNA polymerase and DNA templates containing the surA promoter (data not shown). Also, and as judged by Northern blot analysis, SurA was absent from cells in which the −35 sequence was mutated to TcGAtg (lowercase italic letters indicate additional mutations) and the −10 sequence to TgcAAT (data not shown). A putative terminator for surA was identified by Mfold analysis, which revealed a potential stem-loop structure with a predicted ΔG of −10 kcal/mol followed by a string of U's at an appropriate distance downstream from the start site to terminate the 280-nt transcript.

Knowing the start site for surA, we searched for potential open reading frames (ORFs) in the transcript in which a putative initiation codon (ATG, TTG, or GTG) was preceded at an appropriate distance by a ribosome-binding site. The longest open reading frame that began with a potential initiation codon (ATG) was 38 codons in length, but it was not preceded by a sequence that significantly resembled a ribosome-binding site. Several shorter ORFs of 18, 19, 20, and 21 codons in length that were preceded by a putative initiation codon were also seen, but these also lacked an appropriately positioned ribosome-binding site. Thus, it is unlikely that SurA encodes a peptide.

The gene for SurA is under the indirect control of Spo0A.

Because the abundance of SurA increased markedly upon entry into sporulation, we sought to determine whether transcription of the surA gene was under sporulation control. A lacZ fusion was created in which the reporter gene was joined to the promoter (PsurA) for surA. The results in Fig. 1D (top panel) show that the accumulation of β-galactosidase from the transcription fusion increased sharply after the start of sporulation. This PsurA-directed enzyme synthesis was almost completely blocked in cells that had a mutation in the master regulator Spo0A (Fig. 1D, middle panel). The dependence on Spo0A was, however, indirect, in that high-level and constitutive expression of the PsurA-lacZ fusion was observed in cells doubly mutant for Spo0A and the transition state regulator AbrB. AbrB is a repressor whose synthesis is under the negative control of Spo0A. We therefore conclude that surA is induced during sporulation by a mechanism involving Spo0A-mediated repression of the gene for AbrB.

AbrB is also known to repress the gene (spo0H) for the alternative sigma factor σH. It was therefore conceivable that surA is under σH control and that the increase in PsurA-lacZ expression seen in an AbrB mutant was due to an increase in σH levels. However, the results in Fig. 1D (bottom panel) show that the patterns of PsurA-lacZ expression were similar between cells mutant for AbrB alone and cells doubly mutant for AbrB and σH. In toto, the results indicate that surA is transcribed by σA-RNA polymerase and that it is activated during sporulation by relief of AbrB-mediated repression.

The gene for SurA overlaps with the σK-controlled gene yndL.

The start site for SurA is internal to, and in divergent orientation with, the open reading frame for the adjacent gene yndL such that the two genes overlap by about 50 nt (Fig. 1A). In confirmation of the idea that the 5′ regions of both genes overlap, deletions that precisely removed surA or yndL eliminated the presence of the SurA transcript as judged by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 2A and Materials and Methods).

FIG. 2.

Developmental regulation of yndL. (A) Northern blot of total RNA (5 μg) isolated from wild-type (WT), surA (JS113), and yndL (JS123) cells grown in DS medium at 37°C and collected at hour 1 of sporulation. RNAs were detected using a double-stranded PCR probe for the SurA intergenic region. (B) Northern blot of total RNA (5 μg) isolated from wild-type cells grown in DS medium and collected during exponential growth (log) and at hour 0.5 and hours 1 to 5 of sporulation at 37°C. RNAs were detected using a double-stranded PCR probe for yndL. The molecular weight marker for panels A and B was 5′-end-labeled MspI fragments of pBR322 DNA that had been denatured. (C) Primer extension analysis for yndL. Seventeen micrograms of total RNA was isolated from both a wild-type (ΔgerE, RL3217) and a sigK (ΔgerE ΔspoIVCB, RL3218) strain sporulated by resuspension at 37°C and collected at hour 5 for use as a template for extension with end-labeled primer (oJS265). A, C, G, and T indicate the dideoxy sequencing ladders generated with the same primer and terminated with the corresponding dideoxynucleoside triphosphate. The corresponding cDNA sequence is listed as determined from the DNA sequencing ladder. +1 indicates the 5′ end of the message. The −10 and −35 sequences resemble those recognized by σK-associated RNA polymerase. (D) β-Galactosidase activity for a transcriptional yndL-lacZ fusion in a wild-type (WT) (○) (JS109) and σK mutant (sigK) (•) (ΔspoIVCA, JS122) background. Cultures were sporulated by the resuspension method at 37°C.

Next, we investigated the pattern of expression of yndL, which has been identified as a member of the σK regulon in gene microarray experiments (10). The open reading frame for the gene is 756 bp long, and Northern blot analysis revealed a large transcript (>622 nt) that accumulated to high levels late in sporulation (Fig. 2B). Primer extension analysis revealed an apparent transcription start site that was located at an appropriate distance downstream of sequences that significantly conformed to the canonical “−35” [GAACA, versus the consensus sequence (G/T)(C/A)AC(C/A)] and “−10” (GtATANNNT, versus the consensus sequence GCATANNNT) sequences for promoters recognized by the late-stage sporulation sigma factor σK. Also, the spacing (15 bp) between the −35 and −10 sequences was consistent with that (14 to 16 bp) observed for σK-controlled promoters (10) (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the idea that yndL is transcribed from a σK-controlled promoter, the primer extension product was absent in RNA from cells with a σK mutation (Fig. 2C). Also, a transcriptional fusion of lacZ to yndL was switched on at hour 3 of sporulation in a σK-dependent manner (Fig. 2D).

Conceivably, SurA functions as an antisense RNA to yndL mRNA, but efforts to detect an effect of the surA promoter mutation described above on the level of yndL mRNA were unsuccessful. Alternatively, SurA acts to inhibit translation of yndL mRNA, a possibility that has not been investigated. Finally, mutants of surA and yndL, which were created by replacing the genes with antibiotic resistance cassettes, sporulated at efficiencies that were indistinguishable from the wild type.

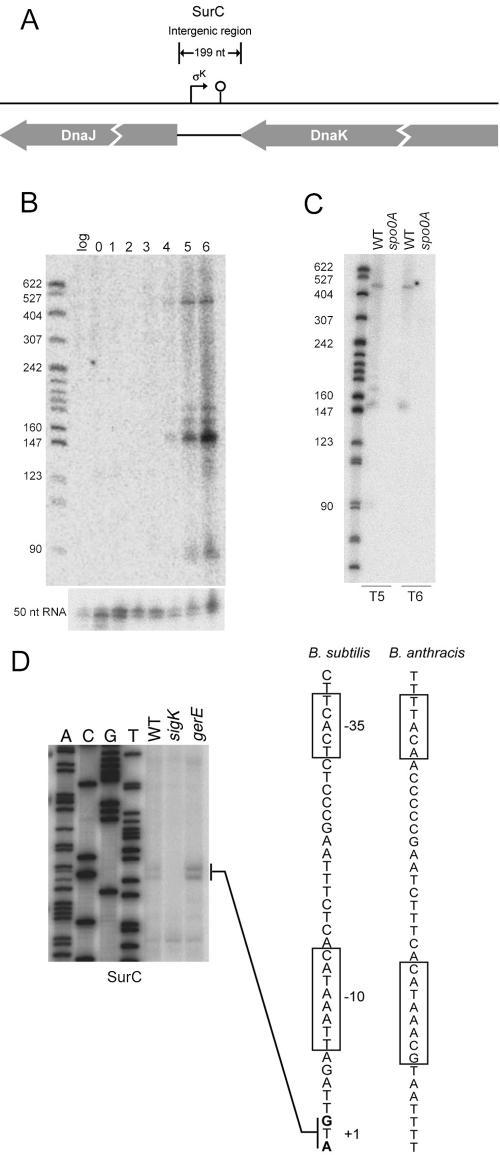

An sRNA produced under σK control from the dnaJ-dnaK intergenic region.

Next, we turn to the dnaJ-dnaK IGR (Fig. 3A). Northern blot analysis using double-stranded DNA probes and strand-specific riboprobes revealed five transcripts (∼450, 180, 170, 150, and 90 nt) all oriented in a left-to-right direction (opposite to that of dnaJ and dnaK) whose appearance commenced at hour 4 of sporulation (Fig. 3B and data not shown). The transcripts were absent in RNA from a deletion of the IGR (data not shown) and in RNA from a spo0A mutant (Fig. 3C), which indicates that their accumulation was under sporulation control. As a control, the bottom of Fig. 3B shows the same RNA samples probed for an unrelated sRNA that was present throughout growth and sporulation.

FIG. 3.

σK dependence of SurC. (A) Schematic diagram of SurC and its neighboring genes. The σK promoter identified by primer extension and 5′ RACE is indicated. A predicted stem-loop terminator is indicated. The diagram is drawn to scale. (B) The upper panel displays a Northern blot of total RNA (5 μg) isolated from wild-type cells grown in DS medium and collected during exponential growth (log) and hours 0 to 6 of sporulation at 37°C. RNAs were detected using a double-stranded PCR probe for the SurC intergenic region. The bottom panel is a control probed with a double-stranded probe for an unrelated small RNA of ∼50 nt. (C) Northern blot of total RNA (5 μg) isolated from wild-type and spo0A (RL2242) cells grown in DS medium and collected at hours 5 and 6 of sporulation at 37°C. The molecular weight marker for panels B and C was 5′-end-labeled MspI fragments of pBR322 DNA that had been denatured. (D) Forty micrograms of total RNA was isolated from wild-type (WT), sigK (ΔspoIVCA, RL3230), and gerE (RL3217) strains grown in DS medium at 37°C and collected at hour 5 for use as a template for extension with end-labeled primer (oJS435). Dideoxy sequencing was conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 2C using primer oJS435. +1 indicates the position of the 5′ end of the transcript. The boxed −10 and −35 sequences resemble the sequence recognized by σK-associated RNA polymerase. The conserved sequence predicted by QRNA for B. anthracis is also displayed.

A 5′ terminus was detected by primer extension analysis, which revealed extension products corresponding to adjacent G and A nucleotides (Fig. 3D). That these nucleotides corresponded to the transcription start site was shown in 5′ RACE experiments that were carried out in the presence or absence of treatment with TAP (4, 6). TAP converts the 5′ triphosphate of the initiating nucleotide(s) in an RNA chain to a 5′ monophosphate, allowing for the ligation of an RNA adaptor (4, 6). RNA to which the adaptor is appended is then reverse transcribed, and the resulting cDNA is subjected to PCR using probes to the adaptor and to the gene whose transcript is being amplified. PCR products whose amplification occurs in a TAP-dependent manner are inferred to originate from a transcription start site. Using this protocol, we detected the same, adjacent nucleotides (G and A) that had been observed by primer extension analysis (Fig. 3D) and in a TAP-dependent manner (data not shown).

The transcription start site revealed by this analysis was located at an appropriate distance downstream of sequences that significantly conformed to the canonical “−35” [TCACt, versus the consensus sequence (G/T)(C/A)AC(C/A)] and “−10” (aCATANNNT versus the consensus sequence GCATANNNT) sequences for promoters recognized by the late-stage sporulation sigma factor σK. The spacing (14 bp) between the −35 and −10 sequences was consistent with that (14 to 16 bp) observed for σK-controlled promoters (10). Consistent with the idea that this was a σK-controlled promoter, the extension products were absent when RNA was prepared from a mutant lacking the sporulation sigma factor (Fig. 3D). Henceforth, we refer to the RNA (or RNAs) originating from the σK-controlled promoter as SurC. As further support for the idea that the region close to and upstream of the start site contained the promoter for surC, we created a strain in which the IGR and an additional 40 bp of upstream sequence were inserted into the chromosome at the amyE locus and from which surC at its normal location had been removed by deletion. When primer extension analysis was carried out with this strain, the same extension products as those detected in the original, wild-type strain were observed.

The simplest hypothesis to explain the results of the Northern blot analysis in Fig. 3B is that all of the transcripts originated from the same surC promoter. We note the presence of a putative rho-independent terminator (with predicted stem-loop secondary structure with a ΔG of ∼10 kcal/mol) located about 90 bp downstream of the start site, and that could account for the 90-nucleotide transcript. Also, a 3′ terminus at position +90 was observed in 3′ RACE experiments (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), which also revealed a 3′ terminus at position +150 (and hence accounted for the 150-nucleotide transcript). Additional 3′ termini corresponding to the other larger transcripts were not detected.

SurC was originally identified by use of the QRNA algorithm, which had detected a region of conserved secondary structure between the 199-bp-long dnaJ-dnaK IGR of B. subtilis and the corresponding 206-bp-long IGR of B. anthracis. Extending this analysis, we note the presence of a putative σK-controlled promoter at a similar position in the B. anthracis IGR (Fig. 3D) and that the predicted region of conserved secondary structures lies within the 90-bp SurC transcript (data not shown).

Some genes that are turned on by σK are also subject to repression by the DNA-binding protein GerE, the product of a gene that is itself under σK control (10). We therefore wondered whether surC was similarly subject to repression by GerE. Indeed, and as seen in Fig. 3D, the level of primer extension products for surC was higher in a gerE mutant than in the wild type. In keeping with our previous analysis, we infer that surC is transcribed in a pulse late in sporulation when its transcription is turned on by σK and then off again by the product of a gene in the σK regulon (10).

Efforts to investigate a function for SurC were complicated by the presence of the promoter for the flanking gene dnaJ in the IGR. A dnaJ null mutant was found to be temperature sensitive for sporulation, sporulating normally at 37°C and at reduced efficiency compared to the wild type at 50°C on solid DS medium (data not shown). A similar phenotype was observed for a mutant in which the IGR (and hence the promoter for dnaJ) was replaced with a spectinomycin resistance cassette. A test of whether the absence of SurC alone causes a measurable defect in sporulation will require the construction of a mutation that eliminates surC without impairing expression of dnaJ.

Finally, we examined the surC sequence for the possible presence of protein-coding sequences. A 60-codon-long open reading frame that started with an ATG at position +69 was found, and an 86-codon-long open reading frame that started with a GTG at position +113 was found. Neither was preceded by a sequence that resembled a ribosome-binding site, and lacZ fused in frame to both generated little β-galactosidase activity. Also, no significant similarities with any other genomes were found using protein-protein BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) for these putative ORFs, including specifically with the B. anthracis genome. These results suggest that the SurC transcripts are not protein-coding genes.

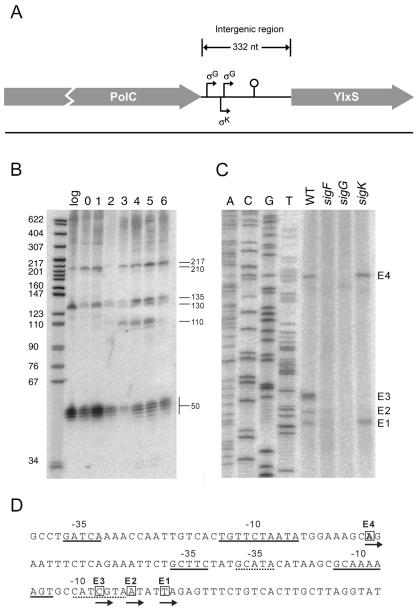

sRNAs produced under σG and σK control from the polC-ylxS intergenic region.

Lastly, we consider the polC-ylxS intergenic region (Fig. 4A). Northern blot analysis using double-stranded DNA probes and strand-specific riboprobes revealed transcripts of approximately 217, 210, 135, 130, and 110 nucleotides and several short transcripts of ∼50 nt (Fig. 4B and data not shown). All of the transcripts were oriented in the same direction (left to right in Fig. 4A) as the flanking genes, and all were absent in RNA isolated from a mutant in which the intergenic region was deleted, indicating that the transcripts originated from the polC-ylxS IGR (data not shown). At least three of the transcripts, those of 217 nt, 135 nt, and 110 nt, were delayed in their appearance until hour 2 of sporulation, raising the possibility that their synthesis was under developmental control.

FIG. 4.

Developmental regulation of polC-ylxS transcripts. (A) Schematic diagram of the polC-ylxS intergenic region. The putative transcriptional start sites, sigma factor regulators, and a rho-independent terminator are indicated. The diagram is drawn to scale. (B) Northern blot of total RNA (5 μg) isolated from wild-type cells grown in DS medium and collected during exponential growth (log) and hours 0 to 6 of sporulation at 37°C. RNAs were detected using a double-stranded PCR probe for the polC-ylxS intergenic region. Transcript sizes are indicated to the right of the blot. The molecular weight marker was 5′-end-labeled MspI fragments of pBR322 DNA that had been denatured. (C) Eleven micrograms of total RNA was isolated from wild-type (WT), sigF (ΔspoIIAC, RL1275), sigG (ΔspoIIIG, RL560), and sigK (ΔspoIVCA, RL3230) strains grown in DS medium, collected during hour 4 of sporulation, and used as a template for extension with end-labeled primer oCR12. Dideoxy sequencing was conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 2C using primer oCR12. E1 to E4 indicate the four extension products observed. (D) The corresponding cDNA sequence is listed as determined from the DNA sequencing ladder in panel C. The putative +1 start sites for E1 to E4 are boxed. The −10 and −35 regions resembling sigma factor recognition sequences are underlined upstream of each +1 (dotted line for E1) (E1, σG; E2-E3, σK; and E4, σG). Arrows below the boxed nucleotides indicate the direction of transcription.

In an effort to detect transcripts arising from promoters under sporulation control, we carried out primer extension analysis, using as template RNA from cells collected at hour 4 of sporulation. This led to the detection of four extension products designated E1 to E4 (Fig. 4C and D). The shortest product (E1) was also detected using RNA from cells collected at hour 3 of sporulation but not with RNA from cells in the exponential phase of growth (data not shown). E1 corresponded to a 5′ terminus that was located at an appropriate distance downstream of a perfect match (GCATA) to a canonical “−35” sequence [GNAT(A/G)] and a perfect match (CATCGTA) to a canonical “−10” sequence [CA(A/T)NNTA] for promoters under σG control. Also, the putative −10 and −35 sequences were separated from each other by an appropriate spacing of 17 to 18 bp for σG-controlled promoters (17; S. Wang, personal communication). Mutant analysis revealed that the E1 extension product was present using RNA from cells lacking σK (RL3230) but was absent using RNA from cells lacking σF (RL560) and σG (RL1275). In toto, and because σG is produced under the control of σF but not σK, the simplest interpretation of these results is that the E1 extension product corresponds to a transcript that arises from a σG-controlled promoter.

Next, we consider the E3 extension product, which was absent in extension reactions using RNA from all three sporulation mutants (Fig. 4C). This could indicate that E3 corresponded to a promoter under σK control, as the production of σK is known to depend on σF and σG. Indeed, E3 defined a 5′ terminus that was located at an appropriate distance downstream of a partial match [GCttC] to the canonical “−35” sequence [(G/T)(A/C)AC(A/C)] and a strong match (GCAaAAAGT) to the canonical “−10” sequence (GCATANNNT) for promoters recognized by σK. Further, the spacing between the two sequences (15 bp) was similar to that observed for σK-controlled promoters (14 to 16 bp) (10). Thus, E3 appeared to correspond to a promoter under the control of the late-appearing mother cell sigma factor. Likewise, E2, which like E3 was absent in extension reactions carried out with RNAs from all three mutants and which defined a 5′ terminus that was only 3 bp downstream of that for E3, is most easily understood as arising from the same σK-controlled promoter. If so, then E2 likely represents an incomplete extension product or a processed form of the primary transcript.

Next, we consider the case of the E4 extension product, which like E1 was absent from extension reactions carried out with RNAs from mutants lacking σF and σG but was present with RNA from a mutant lacking σK (Fig. 4C and D). E4 defined a 5′ terminus that was located at an appropriate distance downstream of a weak match (GAtcA) to the canonical “−35” sequence [GNAT(A/G)] and a five-out-of-seven position match to the canonical “−10” sequence [CA(A/T)NNTA] for σG-controlled promoters. We note that σF- and σG-controlled promoters strongly resemble each other, but in toto and taking into account the results of the mutant analysis, we infer that E4 likely corresponds to a promoter under the control of σG. We conclude that the polC-ylxS IGR contains at least three sporulation-specific promoters.

Using 3′ RACE, we identified a principal 3′ terminus that mapped to a position located ∼207 nt from the left end of the IGR (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). This 3′ end was located just after a putative rho-independent terminator with a predicted ΔG of −16 kcal/mol. Because of the complexity of the transcription pattern from the polC-ylxS intergenic region, we could not definitively assign particular transcripts from the Northern analysis to this putative termination site. Nonetheless, a simple and appealing interpretation of the results is that the ∼135-nt transcript seen in the Northern blot analysis of Fig. 4B that appeared at hour 2 of sporulation corresponds to an sRNA that arose under σG control from the E1 start site and terminated at the inferred, rho-independent terminator.

To investigate a function for these RNAs, we created a deletion mutant in which we replaced the polC-ylxS IGR with a spectinomycin resistance cassette. The results showed that the level of sporulation by the mutant was similar to that for the corresponding wild-type strain (data not shown).

Finally, we address the question of whether the sRNAs are protein-coding sequences. Starting with the left-most putative transcription start site (that defined by E4), we searched for open reading frames in which a putative initiation codon was preceded at an appropriate distance by a ribosome-binding site. Several small open reading frames with potential initiation codons (ATG and TTG) were found between the E4 transcriptional start site and the start codon for the adjacent, protein-coding gene ylxS. Those beginning with ATG were of lengths of 51, 48, 19, and 17 codons. The putative ORFs beginning with TTG were of lengths 50, 32, 27, and 19 codons. Of these, only the 17- and 27-codon-long ORFs were preceded by a sequence that resembled a ribosome-binding site. All of the putative ORFs were analyzed using protein-protein BLAST to look for conservation with other genomes, but significant similarities were not detected, including, in particular, with the corresponding IGR of B. halodurans. We created an in-frame lacZ fusion to the 17-codon open reading frame, which was adjacent to the strongest match for a ribosome-binding site consensus at an appropriate distance from the start codon, but it did not direct the synthesis of significant levels of β-galactosidase (data not shown). Thus, it is likely that the developmentally regulated transcripts from the polC-ylxS IGR are untranslated RNAs.

DISCUSSION

We have presented evidence for the existence of several small, apparently untranslated RNAs that are produced during sporulation and under the control of sporulation-specific regulatory proteins. The production of these sRNAs was found to involve a wide range of transcriptional control mechanisms operating at the start of sporulation and in a cell-specific manner at intermediate to late stages of development. Thus, an sRNA (SurA) from the yndK-yndL IGR, which was produced under the indirect control of Spo0A by a pathway involving AbrB-dependent repression from a promoter recognized by the housekeeping sigma factor σA, was identified. The gene for SurA is partially overlapping with, and in divergent orientation to, an adjacent gene, yndL, that is under the control of the mother cell sigma factor σK. Thus, SurA could represent an antisense RNA for an mRNA that appears late in sporulation. As a second example, an sRNA from the region between the dnaJ and dnaK genes that was synthesized from a promoter under the control of σK was found. Like some other members of the regulon, the gene for SurC was additionally under the negative control of GerE, a late-appearing DNA-binding protein that is itself produced under the control of σK. Genes that are activated by σK and repressed by GerE are thought to be expressed in a pulse at a late stage of development (10). Lastly, a complex pattern of sRNAs for the intergenic region between polC and ylxS was discovered. In this instance, we were able to assign only one sRNA (a species of 135 nt) to a particular promoter (a σG-controlled promoter). Nonetheless, the evidence indicates that the polC-ylxS intergenic region contains two promoters under the control of the forespore-specific transcription factor σG and one under the control of σK.

In no case did we succeed in uncovering a function for the sRNAs detected in this investigation. This is likely to be a significant challenge, as small untranslated RNAs often play a subtle, fine-tuning role in the control of gene expression (12), and not infrequently their function is masked by redundancy (24). Nevertheless, among the sRNAs reported here, the one most likely to be of functional significance is SurC, in that it and its σK-controlled promoter are conserved with the distantly related endospore-forming bacterium B. anthracis. We interpret this conservation as indicating that SurC somehow contributes to spore formation. An appealing possibility is that the longest of the transcripts (∼450 nt) apparently originating from the surC promoter extends into the downstream, and convergently oriented, dnaK gene. Conceivably, these transcripts act as antisense RNAs, promoting the degradation of dnaK mRNA or impeding its translation. If so, then perhaps the function of SurC is to attenuate the production of the DnaK molecular chaperone (33) at a time when the synthesis and assembly of protein components of the spore coat are taking place in the mother cell chamber of the sporangium.

Generally speaking, we speculate that sporulation-specific sRNAs, such as those described here, play a fine-tuning role in sporulation gene expression, helping to optimize the efficiency of spore formation. Sporulation is orchestrated by the temporally and spatially controlled expression of over 500 genes. It is appealing to imagine that sRNAs help coordinate the levels of expression of various developmental genes with each other. Additionally, sRNAs could play a regulatory role in helping to adjust the levels of expression of various sporulation genes in response to environmental conditions. It is commonly assumed that the program of sporulation is hard-wired after the initiation phase (that is, after the stage of asymmetric division). Conceivably, however, the levels of expression of certain sporulation genes are responsive to environmental conditions at intermediate to late stages of development. If so, then some sRNAs could play a role in adjusting sporulation gene expression in response to nutritional or other conditions.

Given the relative ease with which we uncovered sRNAs produced under sporulation control, it is not unreasonable to imagine that many more sporulation-specific sRNAs are waiting to be discovered. This raises the intriguing possibility that the known protein-coding genes under sporulation control (of which there are more than 500) may represent an incomplete picture of the full repertoire of developmentally controlled genes. An important challenge for the future will be to exhaustively identify developmentally regulated genes for sRNAs and to elucidate the roles of these sRNAs in sporulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Laub for his guidance in setting up and running the QRNA program, C. Roehrig for helping to dissect the polC-ylxS IGR, S. Wang for sharing data regarding σF and σG recognition sequences, M. Wyss for comments on the paper, and the members of the Losick laboratory for helpful advice and discussion. We also thank J.-M. Lee and A. Muffler for microarray analysis of B. subtilis.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM18568 to R.L.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altuvia, S., D. Weinstein-Fischer, A. Zhang, L. Postow, and G. Storz. 1997. A small, stable RNA induced by oxidative stress: role as a pleiotropic regulator and antimutator. Cell 90:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altuvia, S., A. Zhang, L. Argaman, A. Tiwari, and G. Storz. 1998. The Escherichia coli OxyS regulatory RNA represses fhlA translation by blocking ribosome binding. EMBO J. 17:6069-6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando, Y., S. Asari, S. Suzuma, K. Yamane, and K. Nakamura. 2002. Expression of a small RNA, BS203 RNA, from the yocI-yocJ intergenic region of Bacillus subtilis genome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 207:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argaman, L., R. Hershberg, J. Vogel, G. Bejerano, E. G. Wagner, H. Margalit, and S. Altuvia. 2001. Novel small RNA-encoding genes in the intergenic regions of Escherichia coli. Curr. Biol. 11:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrick, J. E., N. Sudarsan, Z. Weinberg, W. L. Ruzzo, and R. R. Breaker. 2005. 6S RNA is a widespread regulator of eubacterial RNA polymerase that resembles an open promoter. RNA 11:774-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bensing, B. A., B. J. Meyer, and G. M. Dunny. 1996. Sensitive detection of bacterial transcription initiation sites and differentiation from RNA processing sites in the pheromone-induced plasmid transfer system of Enterococcus faecalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7794-7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, B. M., M. Quinones, J. Pratt, Y. Ding, and M. K. Waldor. 2005. Characterization of the small untranslated RNA RyhB and its regulon in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 187:4005-4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Saizieu, A., U. Certa, J. Warrington, C. Gray, W. Keck, and J. Mous. 1998. Bacterial transcript imaging by hybridization of total RNA to oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:45-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Saizieu, A., C. Gardes, N. Flint, C. Wagner, M. Kamber, T. J. Mitchell, W. Keck, K. E. Amrein, and R. Lange. 2000. Microarray-based identification of a novel Streptococcus pneumoniae regulon controlled by an autoinduced peptide. J. Bacteriol. 182:4696-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichenberger, P., M. Fujita, S. T. Jensen, E. M. Conlon, D. Z. Rudner, S. T. Wang, C. Ferguson, K. Haga, T. Sato, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2004. The program of gene transcription for a single differentiating cell type during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Biol. 2:e328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink, P. S., A. Soto, G. S. Jenkins, and K. S. Rupert. 1997. Expression of small RNAs by Bacillus sp. strain PS3 and B. subtilis cells during sporulation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 153:387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman, S. 2004. The small RNA regulators of Escherichia coli: roles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:303-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 180:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harwood, C. R., and S. M. Cutting. 1990. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 16.Helmann, J. D. 1995. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma A-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2351-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmann, J. D., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 2002. RNA polymerase and sigma factors, p. 289-312. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Johansson, J., and P. Cossart. 2003. RNA-mediated control of virulence gene expression in bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 11:280-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawano, M., A. A. Reynolds, J. Miranda-Rios, and G. Storz. 2005. Detection of 5′- and 3′-UTR-derived small RNAs and cis-encoded antisense RNAs in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:1040-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reference deleted.

- 21.Kolkman, M. A., and E. Ferrari. 2004. The fate of extracellular proteins tagged by the SsrA system of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 150:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lease, R. A., and M. Belfort. 2000. Riboregulation by DsrA RNA: trans-actions for global economy. Mol. Microbiol. 38:667-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, J. M., S. Zhang, S. Saha, S. Santa Anna, C. Jiang, and J. Perkins. 2001. RNA expression analysis using an antisense Bacillus subtilis genome array. J. Bacteriol. 183:7371-7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenz, D. H., K. C. Mok, B. N. Lilley, R. V. Kulkarni, N. S. Wingreen, and B. L. Bassler. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lockhart, D. J., H. Dong, M. C. Byrne, M. T. Follettie, M. V. Gallo, M. S. Chee, M. Mittmann, C. Wang, M. Kobayashi, H. Horton, and E. L. Brown. 1996. Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 14:1675-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loria, A., and T. Pan. 2001. Modular construction for function of a ribonucleoprotein enzyme: the catalytic domain of Bacillus subtilis RNase P complexed with B. subtilis RNase P protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:1892-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Losick, R., P. Youngman, and P. J. Piggot. 1986. Genetics of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 20:625-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masse, E., F. E. Escorcia, and S. Gottesman. 2003. Coupled degradation of a small regulatory RNA and its mRNA targets in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 17:2374-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masse, E., and S. Gottesman. 2002. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molle, V., M. Fujita, S. T. Jensen, P. Eichenberger, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2003. The Spo0A regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1683-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura, K., Y. Imai, A. Nakamura, and K. Yamane. 1992. Small cytoplasmic RNA of Bacillus subtilis: functional relationship with human signal recognition particle 7S RNA and Escherichia coli 4.5S RNA. J. Bacteriol. 174:2185-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostberg, Y., I. Bunikis, S. Bergstrom, and J. Johansson. 2004. The etiological agent of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, appears to contain only a few small RNA molecules. J. Bacteriol. 186:8472-8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyes, D. Y., and H. Yoshikawa. 2002. DnaK chaperone machine and trigger factor are only partially required for normal growth of Bacillus subtilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66:1583-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivas, E., and S. R. Eddy. 2001. Noncoding RNA gene detection using comparative sequence analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivas, E., R. J. Klein, T. A. Jones, and S. R. Eddy. 2001. Computational identification of noncoding RNAs in E. coli by comparative genomics. Curr. Biol. 11:1369-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaeffer, P., J. Millet, and J. P. Aubert. 1965. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 54:704-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silvaggi, J. M., J. B. Perkins, and R. Losick. 2005. Small untranslated RNA antitoxin in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 187:6641-6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sledjeski, D. D., A. Gupta, and S. Gottesman. 1996. The small RNA, DsrA, is essential for the low temperature expression of RpoS during exponential growth in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 15:3993-4000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterlini, J. M., and J. Mandelstam. 1969. Commitment to sporulation in Bacillus subtilis and its relationship to development of actinomycin resistance. Biochem. J. 113:29-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storz, G., S. Altuvia, and K. M. Wassarman. 2005. An abundance of RNA regulators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74:199-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuma, S., S. Asari, K. Bunai, K. Yoshino, Y. Ando, H. Kakeshita, M. Fujita, K. Nakamura, and K. Yamane. 2002. Identification and characterization of novel small RNAs in the aspS-yrvM intergenic region of the Bacillus subtilis genome. Microbiology 148:2591-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trotochaud, A. E., and K. M. Wassarman. 2004. 6S RNA function enhances long-term cell survival. J. Bacteriol. 186:4978-4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trotochaud, A. E., and K. M. Wassarman. 2005. A highly conserved 6S RNA structure is required for regulation of transcription. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wach, A. 1996. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast 12:259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilderman, P. J., N. A. Sowa, D. J. FitzGerald, P. C. FitzGerald, S. Gottesman, U. A. Ochsner, and M. L. Vasil. 2004. Identification of tandem duplicate regulatory small RNAs in Pseudomonas aeruginosa involved in iron homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:9792-9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youngman, P., J. B. Perkins, and R. Losick. 1984. Construction of a cloning site near one end of Tn917 into which foreign DNA may be inserted without affecting transposition in Bacillus subtilis or expression of the transposon-borne erm gene. Plasmid 12:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.