Abstract

Phosphotransacetylase (EC 2.3.1.8) catalyzes reversible transfer of the acetyl group from acetyl phosphate to coenzyme A (CoA), forming acetyl-CoA and inorganic phosphate. Two crystal structures of phosphotransacetylase from the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila in complex with the substrate CoA revealed one CoA (CoA1) bound in the proposed active site cleft and an additional CoA (CoA2) bound at the periphery of the cleft. The results of isothermal titration calorimetry experiments are described, and they support the hypothesis that there are distinct high-affinity (equilibrium dissociation constant [KD], 20 μM) and low-affinity (KD, 2 mM) CoA binding sites. The crystal structures indicated that binding of CoA1 is mediated by a series of hydrogen bonds and extensive van der Waals interactions with the enzyme and that there are fewer of these interactions between CoA2 and the enzyme. Different conformations of the protein observed in the crystal structures suggest that domain movements which alter the geometry of the active site cleft may contribute to catalysis. Kinetic and calorimetric analyses of site-specific replacement variants indicated that there are catalytic roles for Ser309 and Arg310, which are proximal to the reactive sulfhydryl of CoA1. The reaction is hypothesized to proceed through base-catalyzed abstraction of the thiol proton of CoA by the adjacent and invariant residue Asp316, followed by nucleophilic attack of the thiolate anion of CoA on the carbonyl carbon of acetyl phosphate. We propose that Arg310 binds acetyl phosphate and orients it for optimal nucleophilic attack. The hypothesized mechanism proceeds through a negatively charged transition state stabilized by hydrogen bond donation from Ser309.

Acetate is an end product of the energy-yielding metabolism of nearly all fermentative microbes in the domain Bacteria in which acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) is converted to acetate by phosphotransacetylase (Pta) (equation 1) and acetate kinase (equation 2) coupled to the synthesis of ATP. Acetate also is the growth substrate for methane-producing archaea. Thus, acetate is a major intermediate in the global carbon cycle, and acetate conversion to methane is responsible for the majority of biological methane production (7). In Methanosarcina species, Pta and acetate kinase function in the opposite direction to catalyze the ATP-dependent activation of acetate to acetyl-CoA for cleavage of the C−C bond of acetate by the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase, which releases the methyl group for eventual reduction to methane.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

The kinetic and catalytic mechanisms of acetate kinase are well characterized; however, Pta has been studied in considerably less detail, although the enzyme from the fermentative anaerobe Clostridium kluyveri was purified in the early 1950s (35). Kinetic analyses of Ptas from C. kluyveri and Veillonella alcalescens have suggested that rather than a ping-pong mechanism, the mechanism likely proceeds through formation of a ternary complex (20, 28). In a reexamination of the C. kluyveri Pta workers attempted to detect an acetyl-enzyme intermediate; however, no isotope exchange from labeled acetyl phosphate into either acetyl-CoA or inorganic phosphate was observed in the absence of free CoA, and attempts to isolate an acetyl-Pta intermediate were unsuccessful, which is consistent with a ternary complex mechanism (9). Although numerous genetic and physiological studies have continued to demonstrate the universal function of Pta in acetate metabolism in diverse microbes (1, 4, 6, 8, 15, 17, 24, 25, 27, 30, 32, 38), mechanistic analyses of the enzyme were abandoned until there was an investigation of Pta from the archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila, which obtains energy for growth by converting acetate to methane (22).

Cloning of the gene and heterologous expression of Pta from M. thermophila allowed the large-scale production of protein required for structural studies, biochemical analyses, and the use of site-specific replacement to analyze the function of specific residues (22). Cys312 was predicted to be present in the active site, although it is not essential for catalysis (31). Arg87 and Arg133 were proposed to interact with the 3′ and 5′ phosphate groups of CoA, respectively (12), while Arg310 was found to be essential for catalysis, although its role was not defined further (31). In spite of the insight gained from the site-specific replacement studies, key questions remained. The architecture of the active site was unknown, and, other than the residues listed above, our understanding of interactions between the enzyme and the substrates was incomplete.

The crystal structure of the M. thermophila enzyme was the first structure to be solved for a Pta from any organism and remains one of only two examples published to date (13, 42); however, neither of the structures that have been determined contains bound substrates. In the current study we closed this gap by incorporating information deduced from two crystal structures in complex with CoA together with kinetic analyses of site-specific replacement variants in order to propose a catalytic mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

CoA-Li salt (yeast), acetyl-CoA-Li salt (enzymatically prepared), and acetyl phosphate-LiK salt were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dithiothreitol, NH4Cl, (NH4)2SO4, HEPES, KCl, K2HPO4, Tris base, and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were purchased from Fisher Scientific Company (Newark, DE) and were the highest grade available. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells were purchased from Novagen Inc. (Madison, WI). All chromatographic resins and supports were purchased from Amersham Biosciences Corporation (Piscataway, NJ).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Mutagenesis was performed by the oligonucleotide-directed in vitro mutagenesis method (18), using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid pML702 (22), a derivative of the expression vector pT7-7 (36) containing the M. thermophila pta gene, was the target for mutagenesis using the primers listed in Table 1. Mutations were verified by dye termination cycle sequencing using an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) at the Nucleic Acid Facility at Pennsylvania State University.

TABLE 1.

Mutagenic oligonucleotide primers

| Mutant | Primer sequencesa |

|---|---|

| Ser309Ala | 5′ CCA ATT AAC GAC CTG GCC AGA GGC TGC AGC GAC 3′ |

| 5′ GTC GCT GCA GCC TCT GGC CAG GTC GTT AAT TGG 3′ | |

| Ser309Cys | 5′ CCA ATT AAC GAC CTG TGC AGA GGC TGC AGC GAC 3′ |

| 5′ GTC GCT GCA GCC TCT GCA CAG GTC GTT AAT TGG 3′ | |

| Ser309Thr | 5′ CCA ATT AAC GAC CTG ACC AGA GGC TGC AGC GAC 3′ |

| 5′ GTC GCT GCA GCC TCT GGT CAG GTC GTT AAT TGG 3′ | |

| Arg310Ala | 5′ CCA ATT AAC GAC CTG TCC GCC GGC TGC AGC GAC 3′ |

| 5′ GTC GCT GCA GCC GGC GGA CAG GTC GTT AAT TGG 3′ | |

| Arg310Gln | 5′ CCA ATT AAC GAC CTG TCC CAG GGC TGC AGC GAC 3′ |

| 5′ GTC GCT GCA GCC CTG GGA CAG GTC GTT AAT TGG 3′ | |

| Arg310Lys | 5′ CCA ATT AAC GAC CTG TCC AAA GGC TGC AGC GAC 3′ |

| 5′ GTC GCT GCA GCC TTT GGA CAG GTC GTT AAT TGG 3′ | |

| Asp316Glu | 5′ GGC TGC AGC GAC GAA GAA ATT GTC GGT GCC GTT 3′ |

| 5′ AAC GGC ACC GAC AAT TTC TTC GTC GCT GCA GCC 3′ |

The mutated codon in each primer is indicated by boldface type.

Heterologous expression and purification of Pta.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with wild-type or mutagenized plasmid pML702 were grown to an A600 of 0.6 at 37°C with shaking in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. The temperature was reduced to 15°C, and IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, after which incubation was continued for 12 to 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) containing 180 mM KCl at a ratio of 1 g cells/ml, and disrupted by two passages through a French pressure cell (4°C, 20,000 lb/in2). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (75,000 × g, 2 h), brought to 45% (NH4)2SO4 saturation by slow addition of 100% (NH4)2SO4, and stirred overnight at 4°C. The solution was centrifuged (75,000 × g, 2 h), and the supernatant was applied to a butyl Sepharose column equilibrated with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) containing 1.4 M (NH4)2SO4. Pta eluted at 600 mM (NH4)2SO4 when a descending linear gradient of 1.4 M to 300 mM (NH4)2SO4 was used. The fractions containing Pta activity were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 4 liters of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2). The dialyzed solution was applied to a Source-Q anion-exchange column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2). Pta eluted at 200 mM KCl when an ascending linear gradient of 0 to 500 mM KCl was used. The preparation was homogeneous as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford dye-binding assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Size exclusion chromatography.

A 120-ml Sephacryl S200 column was equilibrated with 5 column volumes of 25 mM Tris (pH 7.2) containing 180 mM KCl at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. A calibration curve for the column was obtained using RNase A (13.7 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), and the void volume was determined using Blue Dextran 2000 (2,000 kDa). To determine the molecular mass of Pta, a 1-ml sample of a 1-mg/ml Pta solution was loaded onto the column, and the retention volume was measured.

Analytical ultracentrifugation.

Sedimentation equilibrium measurements were obtained using a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with a four-sector rotor with standard six-channel cells. Experiments were performed at 20°C at a speed of 13,500 rpm, and the absorbance-versus-radius distributions were recorded at 280 nm. Samples were considered to have reached equilibrium when scans taken 6 h apart were identical. The partial specific volume of Pta calculated from the sequence is 0.746 cm3/g. The sedimentation equilibrium data were evaluated with the Nonlin analysis program (16) using a nonlinear least-squares curve-fitting regression.

Data collection and structure determination.

Pta was crystallized initially as previously described using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method (14). Pta crystals were soaked with 5 mM CoA overnight, and the resulting complex crystals were transferred into fomblin oil prior to cryocooling in liquid nitrogen. Several crystals were tested for diffraction, and all of them belonged to the I41 crystal form described previously (13); a 2.7-Å data set was collected from one crystal at beam line X26C at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at a wavelength of 1.1 Å with a Quantum IV ADSC charge-coupled device detector. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with the program MOLREP (37) by using apo-Pta (CD dimer of PDB entry 1QZT) as the search model. Refinement, including TLS refinement, was carried out with REFMAC (26) and was completed by manual addition of three CoA molecules and two sulfate molecules and automated addition of solvent molecules with ARP (29). Subsequently, Pta at a concentration of 5 mg/ml was cocrystallized in the presence of 5 mM CoA against a reservoir solution containing 1.1 M sodium citrate and 0.1 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.5). The crystals were rapidly transferred into mother liquor containing 5% and 10% glycerol and then cryocooled in liquid N2. These crystals belonged to the same I41 space group with closely related unit cell dimensions. A data set with 2.15-Å resolution was collected at beam line X26C at the NSLS at a wavelength of 1.1 Å with a Quantum IV ADSC charge-coupled device detector. Refinement was initiated by rigid body refinement, followed by conjugate gradient refinement in REFMAC, including TLS refinement. All temperature factors reported below include the contribution from the TLS refinement. Two CoA molecules were added manually, and this was followed by automated solvent building with ARP.

Pta activity assay.

The rate of the reaction was determined at 23°C by monitoring the change in absorbance at 233 nm concomitant with formation of the thioester bond of acetyl-CoA (ɛ = 4,360 M−1), using a 0.1-cm-path-length quartz cuvette in a Hewlett-Packard 8452A diode array spectrophotometer. The standard reaction mixture (200 μl) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 20 mM NH4Cl, 20 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05 μg/ml Pta, and the appropriate substrate for the experiment. Reactions were initiated by addition of the second substrate.

Isothermal titration calorimetry.

Prior to each experiment a 2-ml aliquot of Pta was dialyzed against 4 liters of filtered buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 20 mM KCl, and 20 mM NH4Cl at 4°C overnight. The dialysis buffer was subsequently used as the diluent to prepare the ligand solution for titration. The cell volume was 1.42 ml, and the syringe volume was 300 μl. To analyze CoA binding to wild-type Pta, CoA was titrated in 59 5-μl injections into Pta concentrations ranging from 30 to 100 μM to obtain final molar ratios of CoA to Pta ranging from 2:1 to 4:1 at the end of the experiment. Three experiments were performed with Pta and CoA at 30°C. Blank injections of CoA into buffer were performed to estimate the heat of injection, mixing, and dilution, and the results revealed that the heat effects were less than 0.5% of the Pta-CoA binding heat.

To analyze acetyl phosphate binding to wild-type and variant Ptas, protein and ligand samples were prepared as described above, and each titration was performed in duplicate at 25°C. The ligand was titrated into the samples as follows: 630 μM acetyl phosphate in 59 5-μl injections into 90 μM wild-type Pta, 5 mM acetyl phosphate in 30 × 10-μl injections into Arg310Ala, 630 μM acetyl phosphate in 59 5-μl injections into Arg310Gln, and 1 mM acetyl phosphate in 59 5-μl injections into 70 μM Arg310Lys. Blank injections of acetyl phosphate into buffer were performed to estimate the heat of injection, mixing, and dilution, and the results revealed heat effects of approximately 5% of the Pta-acetyl phosphate binding heat, which were subtracted from the baseline for each titration curve.

For every injection the binding enthalpy (kcal/mol of injectant) was calculated by integration of the peak area using the ORIGIN software provided by Microcal. The binding enthalpy was plotted as a function of the molar ratio and was fitted to equations describing a single binding site for acetyl phosphate or two independent binding sites for CoA (40), and the association constant (KA) (KA = 1/KD, where KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant), binding stoichiometry (n), and binding enthalpy (ΔH) were determined through curve fitting with ORIGIN. The extracted n values ranged from 0.8 to 1.3 for the variants, and n was fixed at 1 for consistent curve fitting. The changes in free energy (ΔG) were calculated with the equation ΔG = −RTln(KA), where R is the universal gas constant and T is the absolute temperature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Gross architecture of Pta-CoA complexes.

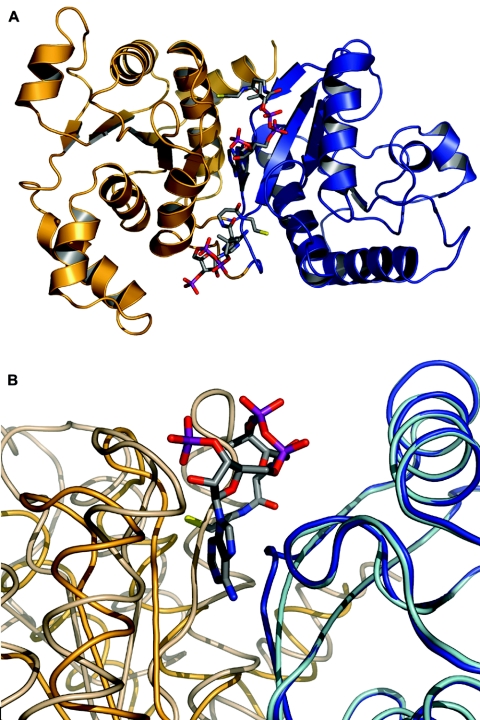

Crystals of Pta with bound CoA were obtained by soaking apo-Pta crystals with CoA and also by cocrystallizing the enzyme with CoA (Tables 2 and 3). The structure of the Pta-CoA complex obtained by soaking (PDB identifier 2AF3) was refined at a resolution of 2.7 Å to an R-factor of 0.215 (Rfree, 0.290). The crystals belonged to space group I41 and contained one dimer per unit cell (with subunits referred to as monomers A and B). The crystals of the previously described M. thermophila apo-Pta structure (13) belong to space group P41 and contain two dimers per unit cell (with subunits referred to as monomers A-B and C-D). The Cα trace of each monomer of the soaked structure revealed two α/β/α domains; residues 1 to 144 and 301 to 333 form domain I, while domain II is composed of residues 145 to 300. This structure is identical to the previously described apo-Pta structure (Fig. 1A). The two domains are arranged side by side and form an almost continuous β-sheet. This arrangement creates a prominent cleft between the two domains, which, based on sequence conservation and kinetic analysis of site-directed variants, was previously proposed to contain the active site (13). Domain II is responsible for dimerization, and relative to this core, the orientations of domain I in the A-B dimer of the apo-Pta structure have been reported to be in open (monomer A) and closed (monomer B) conformations that differ by a 20° rotation of domain I relative to domain II. Both monomers of the C-D dimer of the apo-Pta structure are in an intermediate conformation (not shown). Superimposition of the monomers in the soaked structure reported here revealed that they differ by an 8° rotation of domain I, resulting in a root mean square (RMS) deviation of 1.05 Å (not shown). This shift in domain I leads to differences in the geometry of the proposed active site cleft between the two domains, which result in an open conformation for monomer A and a partially closed conformation for monomer B (Fig. 1B). Monomer B of the soaked structure exhibited significantly higher B-factors (114.1 Å2 for monomer B, compared with 63.6 Å2 for monomer A), and long stretches in domain I of monomer B appear to be highly flexible based on the poor quality of the electron density maps.

TABLE 2.

Data collection statisticsa

| Parameter | Soaked structure | Cocrystallized structure |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 50-2.7 | 50-2.15 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | ||

| a | 114.5 | 116.5 |

| c | 127.8 | 127.5 |

| Completeness | 0.950 (0.967) | 0.984 (0.991) |

| Mean redundancy | 4.48 | 5.81 |

| Rsym | 0.052 (0.379) | 0.065 (0.444) |

| 〈I/sigI〉 | 24.2 (3.1) | 28.7 (2.6) |

Rsym = ∑hkl∑i|Ii − 〈I〉|/∑hkl∑iIi, where Ii is the ith measurement and 〈I〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of I. 〈I/sigI〉 indicates the average intensity divided by the standard deviation. The numbers in parentheses are the highest resolution data shell in each dataset.

TABLE 3.

Refinement statisticsa

| Parameter | Soaked structure | Cocrystallized structure |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution limits (Å) | 20-2.7 | 20-2.15 |

| No. of reflections used in refinement | 22,784 | 43,035 |

| No. of protein atoms/solvent atoms/cofactor atoms | 4,925/60/149 | 4,918/288/96 |

| Rcryst (Rfree) | 0.215 (0.290) | 0.203 (0.272) |

| Deviations from ideal values in: | ||

| Bond distances (Å) | 0.015 | 0.018 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.610 | 1.761 |

| Torsion angles (°) | 7.558 | 7.158 |

| Chiral-center restraints (Å3) | 0.101 | 0.096 |

| Plane restraints (Å) | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| VDW repulsions (Å) | 0.258 | 0.164 |

| Main chain B-factors (Å2) | 0.530, 0.931 | 0.837, 1.091 |

| Side chain B-factors (Å2) | 1.572, 2.473 | 2.012, 3.126 |

| DPI based on Rfree (Å) | 0.355 | 0.210 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | 87.5/11.6/0.5/0.3 | 86.7/11.5/1.3/0.5 |

| Average B-factors of atoms in the protein/solvent/CoA1/CoA2 (Å2) | 88.9/63.9/82.8/117.5 | 78.1/64.5/72.9/NA |

Rcryst = ∑hkl||Fo| − |Fc||/∑hkl|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes. Rfree is the same as Rcryst for 5% of the data randomly omitted from refinement. The number of reflections excludes the Rfree subset. DPI is the data precision index based on the free R-factor as calculated by REFMAC (26). The Ramachandran statistics indicate the fraction of residues in the most favored, additionally allowed, generously allowed, and disallowed regions of the Ramachandran diagram, respectively, as defined by PROCHECK (21). NA, not applicable.

FIG. 1.

Architecture of and domain movements in the Pta monomer. (A) Ribbon diagram of monomer A of the soaked structure with two bound CoA molecules. Domain II is blue, and domain I is gold. Both CoA molecules are shown in an “all-bonds” representation. CoA1 is toward the top, and CoA2 is near the bottom. (B) Superimposition of monomer A from the CoA soaked structure, which is in the open conformation (domain II is blue, and domain I is gold), onto monomer B of the previously published apo-Pta structure (PDB identifier 1QZT), which is in the closed conformation (domain II is cyan, and domain I is wheat). CoA1 from the soaked structure is shown in an “all-bonds” representation. Figures 1 to 3 and 5 were generated with PyMOL (5).

Crystals of Pta with CoA bound were also obtained by cocrystallization (PDB identifier 2AF4), and these crystals belong to the same I41 space group as the soaked structure, with only slightly modified unit cell dimensions (Table 2). The cocrystallized structure was refined at a resolution of 2.15 Å to an R-factor of 0.203 (Rfree, 0.272). Compared to the soaked structure, the two monomers are more similar to each other in this structure, as shown by an overall RMS deviation of 0.8 Å for the Cα atoms of monomers A and B and RMS deviations for the Cα atoms of residues in domains I (residues 3 to 140) and II (residues 151 to 300) of 0.64 Å and 0.32 Å, respectively. As a consequence, the cleft between domains I and II has similar dimensions in the two monomers, and both monomers are in the open conformation, similar to monomer A of the apo structure (not shown). As in the soaked structure, domain I of monomer B of the cocrystallized structure exhibits considerable flexibility, as shown by high B-factors (110.4 Å2 for domain I and 91.4 Å2 for the entire monomer B, compared to 75.8 Å2 for domain II of monomer B and 65.0 Å2 for the entire monomer A) and correspondingly poorer electron density for monomer B (especially domain I) compared to monomer A, despite the higher resolution.

In the report of the initial purification and characterization of M. thermophila Pta, the authors concluded that the enzyme existed in solution as a monomer (24); however, Pta was found to be a dimer in the previously reported apo-Pta crystal structures (13, 42) and both structures described here. Therefore, the oligomeric state of the enzyme in solution was reexamined. The calculated molecular mass of the Pta monomer is 35,198 Da, and the enzyme migrated in a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel as a single band with an apparent mass of 36 kDa (not shown). Wild-type Pta and the variants described in this paper consistently eluted from a size exclusion column in a single symmetrical peak corresponding to a molecular mass of 70.7 kDa, approximately twice the calculated molecular mass of the Pta monomer. The apparent dimerization of wild-type Pta was investigated further using sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation. The sedimentation data fit a single-species model with no evidence of sample aggregation (not shown). Analysis yielded an apparent molecular mass of 69.5 kDa, which corresponds well to the molecular mass revealed by size exclusion chromatography (70.7 kDa). Thus, we concluded that M. thermophila Pta is a dimer in solution, which is consistent with the dimeric states reported for the Ptas from V. alcalescens, E. coli, and Streptococcus pyogenes (28, 33, 42).

Active site analysis of the Pta-CoA complexes.

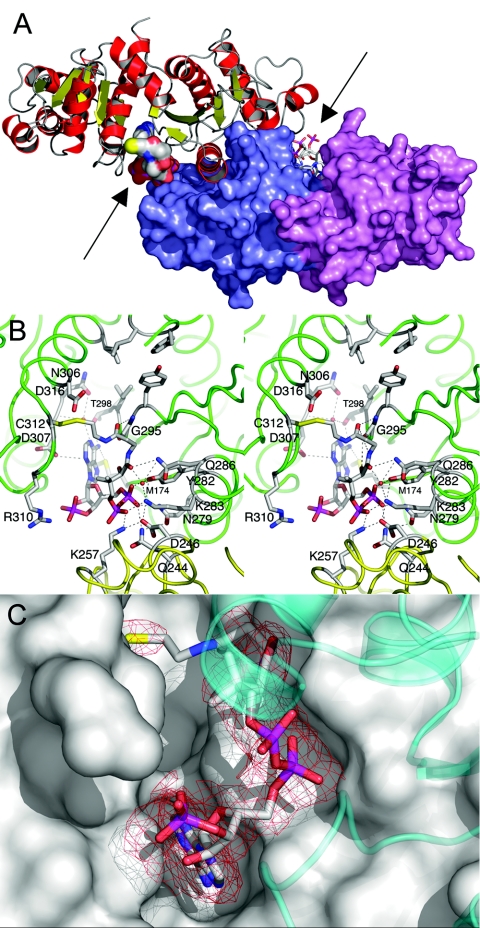

The cocrystallized structure revealed one CoA molecule bound per monomer located in the interdomain cleft that was previously predicted (13) to contain the active site (Fig. 2A). The CoA molecule is contacted by several residues that were determined to be conserved or type conserved (Table 4) by alignment of 32 Pta sequences (13), and the CoA in this site is referred to as CoA1. Figure 2B shows CoA1 bound to monomer A of the cocrystallized structure, and the CoA1 bound to monomer B was positioned similarly (not shown). When we considered only distances of ≤3.5 Å, we found that 13 direct hydrogen bonds are formed between the protein and CoA1 in monomers A and B (Table 4 and Fig. 2B). Of these 13 hydrogen bonds, 11 are present in both monomers (Table 4). In addition, there is a slightly longer polar interaction between the sulfur of Met174 and N-6 of the adenine ring. The electron density appears to be weak in the vicinity of the amide group proximal to the sulfur of CoA, presumably due to a lack of interactions between the enzyme and this region of the cofactor (Fig. 2C). In addition, the sulfur atom of CoA1 is located 2 Å from the side chain of Cys312, and it is covalently linked to this side chain via a disulfide bridge (Fig. 2B). The existence of this linkage is considered a crystallization artifact resulting from cocrystallization under nonreducing conditions. Finally, two water molecules mediate interactions between CoA1 and the enzyme (Fig. 2B). One of the water molecules forms hydrogen bonds to N-1 of the adenine ring and also to Asn306 and Asp307. The other water molecule forms hydrogen bonds to the second amide oxygen of the pantetheine moiety and also to Lys283, Gln286, and Arg287. Three cis peptides involving residue pairs Ala170-Asp171, Gly241-Glu242, and Gly295-Pro296 could be identified in this structure, and the cis peptide involving Gly295-Pro296 was already known from the apo structure (13). The cocrystallized Pta-CoA complex revealed that the Gly295-Pro296 pair forms part of the CoA1 binding pocket and that a trans peptide in this position would lead to steric interference with the pantetheine of the bound CoA1 (not shown). In addition, this cis peptide appears to be important for CoA1 binding as both the backbone O and N of Gly295 form hydrogen bonds to the pantetheine of CoA1 (Table 4). In contrast, the other cis peptides are distant (11 and 27 Å, respectively) from the active site.

FIG. 2.

Structural features of Pta cocrystallized with CoA. (A) Structure of the Pta dimer. Monomer A is shown in a ribbon representation; α-helices are red, β-strands are yellow, and loops are gray. Monomer B is shown in a surface representation; domain I is violet, and domain II is slate blue. The CoA molecules are shown in a van der Waals representation in monomer A and in a stick representation in monomer B and are indicated by arrows. The view is approximately along the twofold axis of the dimer. (B) Stereo diagram of the CoA1 binding site of monomer A. Monomers A and B (green and yellow, respectively) are shown in a loop representation, and residues involved in hydrogen-bonded interactions with the CoA are labeled. In addition, the proposed catalytic residues Arg310 and Asp316, as well as Cys312, which forms the disulfide linkage with CoA, are labeled. Residues Phe4, Leu5, Tyr294, Ile297, and Ile323 (proposed to interact with the methyl group of acetyl phosphate) are near the top and do not have labels. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. Two water molecules, which mediate interactions between the protein and the cofactor, are indicated by red spheres. (C) Omit electron density map of bound CoA1. The difference omit map is red at a contour level of three times the RMS deviation. Weak density is apparent in the vicinity of the amide group proximal to the sulfur of CoA, presumably due to a lack of interactions between the enzyme and this region of the cofactor. Monomer A is shown in a surface representation, and domain II of monomer B is shown as a transparent cyan ribbon diagram.

TABLE 4.

Hydrogen bonds between CoA1 and residues in the Pta-CoA complexes obtained by cocrystallization and soaking

| Hydrogen bond participants

|

Distance (Å)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soaked structure

|

Cocrystallized structure

|

|||||

| CoA moiety | CoA atom | Residue | Residue atom | Monomer A | Monomer A | Monomer B |

| Adenine ring | N-1 | Thr298 | Oγ1 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| N-3 | Asp307b | Oδ1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 | |

| N-6 | Thr298 | Oγ1 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.0 | |

| α-Phosphate | O-1 | Asn279c | Nδ2 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| O-1 | Gln244b,d | Nɛ2 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.1 | |

| O-2 | Tyr282b | OH | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | |

| β-Phosphate | O-4 | Lys257c,d | Nζ | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| O-5 | Lys283c | Nζ | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | |

| O-5 | Lys257c,d | Nζ | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.6 | |

| O-5 | Gln244b,d | Nɛ2 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.3 | |

| 3′ Phosphate | O-8 | Ser128b | Oγ | 2.9 | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| Ribose | O-2′ | Ser128b | Oγ | 2.9 | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| Second amide nitrogen of pantetheine | N-8 | Gly295 | O | 5.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| First amide oxygen of pantetheine | O-5 | Gly295 | N | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Second amide oxygen of pantetheine | O-9 | Gln286 | Nɛ2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| O-9 | Tyr282b | OH | 2.9 | 3.7 | 3.8 | |

| Hydroxyl of pantetheine | O-10 | Tyr282b | OH | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| Sulfur of pantetheine | S-1 | Ser309c | N | 3.0 | NAe | NA |

| S-1 | Cys312 | S | NA | 2.0f | 2.0f | |

Distances that are ≤3.5 Å are considered hydrogen bonds.

Type-conserved residue.

Strictly conserved residue.

Residue originating from adjacent monomer.

NA, not applicable.

The sulfur of panthetheine is covalently linked via a disulfide bridge to Cys312, an artifact resulting from nonreducing cocrystallization conditions.

Surprisingly, the soaked structure revealed that three CoA molecules are bound per Pta dimer. Two CoA molecules are bound to monomer A (Fig. 1A and 3A), and one is bound to monomer B (not shown); one binding site is common to both monomers. The common binding site is different from the CoA1 site in the cocrystallized structure and is referred to as the CoA2 site below. The CoA2 site is located near the entrance to the interdomain cleft (Fig. 3A) in a region where significant positive surface potential is accumulated. In monomer A of the soaked structure, the position of the other CoA is similar to the position of CoA1 in the cocrystallized structure; however, in monomer B of the soaked structure, there is insufficient space for CoA binding to the CoA1 site (Fig. 1B). This is due to movement of domain I, particularly the side chain of Ser307, which prevents CoA1 binding by sterically interfering with the N-3, C-4, C-5, C-6, and N-6 atoms of CoA1. The interactions between CoA1 and Pta are closely related in the two structures (Table 4), but they are somewhat more extensive in the soaked structure. Applying a 3.5-Å cutoff resulted in 16 direct hydrogen bonds between CoA1 and the protein. In addition, the slightly longer polar interaction involving the sulfur of Met174 and N-6 of the adenine ring observed in the cocrystallized structure is also present. One key difference is that the disulfide linkage between CoA1 and Cys312 in monomer A of the cocrystallized structure is replaced by a hydrogen bond between the pantetheine sulfur and the backbone N of Ser309 in the soaked structure (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Details of the CoA-soaked structure. (A) Structure of the active site cleft of monomer A in the soaked structure with CoA1 at the top and CoA2 at the bottom (enclosed in circles). Monomer A is shown in a surface representation and is color coded according to the vacuum electrostatic surface potential. Monomer B is shown as a gray ribbon diagram. (B) Stereo diagram of the CoA2 binding site in monomer A. Monomer A is shown in a green loop representation, and residues involved in hydrogen-bonded interactions with the CoA are labeled. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. The position of Arg133, which is engaged in ionic interactions with the α-phosphate of the pyrophosphate moiety, is also shown.

In the soaked structure, CoA1 has an average B-factor of 82.8 Å2, while CoA2 exhibits considerably higher conformational flexibility (average B factor, 100.8 Å2). As judged by the number of contacts with the enzyme, the CoA2 molecule does not interact with Pta as tightly as CoA1, although there are significant interactions between Pta and CoA2 (Fig. 3B). The 3′ phosphate group of CoA2 has ionic and hydrogen-bonded interactions with Arg87, while the α-phosphate of the pyrophosphate linkage is stabilized by electrostatic interactions with Arg133, but at a distance that is too great for the formation of hydrogen bonds (Fig. 3B). The interactions observed for Arg87 and Arg133 are in excellent agreement with kinetic analyses of site-specific variants, which predicted that Arg87 interacts with the 3′ phosphate and Arg133 interacts with one of the 5′ phosphates (12). Atoms N-1 and N-6 of the adenine base in CoA2 were observed to hydrogen bond to Ala148 in both monomers, and these interactions were the only hydrogen bond interactions observed between CoA2 and monomer B. N-6 is also close (∼4.2 and 4.8 Å in monomers A and B, respectively) to the S atom of Met174, the same residue which also interacts with N-6 of CoA1. In monomer A, O-7 and O-8 of the 3′ phosphate hydrogen bond to Arg87, and the pantetheine sulfur hydrogen bonds with the backbone N and Oɛ1 of Glu176. The lack of hydrogen bonding to the pantetheine moiety suggests that the high B-factors for CoA2 are largely attributable to the mobility of this moiety. However, there are multiple van der Waals interactions between CoA2 and nearby residues, which contribute to binding, which is reflected by the fact that 780 Å2 of accessible surface area is buried in the complex. In the case of CoA1 this value is even larger (1,080 Å2), further suggesting that CoA1 is bound more tightly to the enzyme than CoA2.

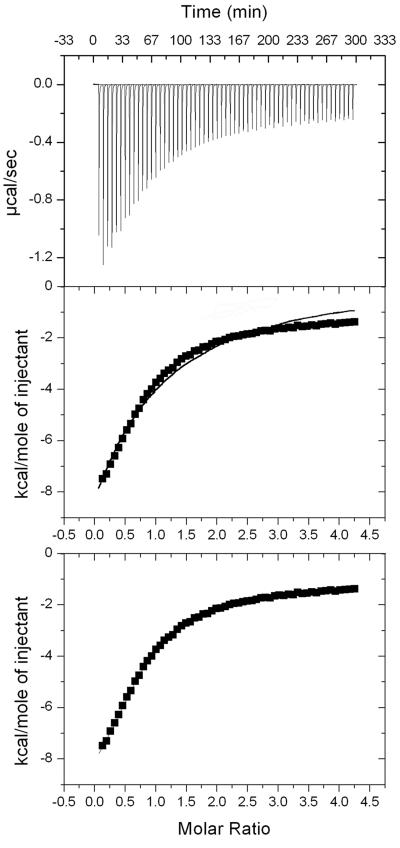

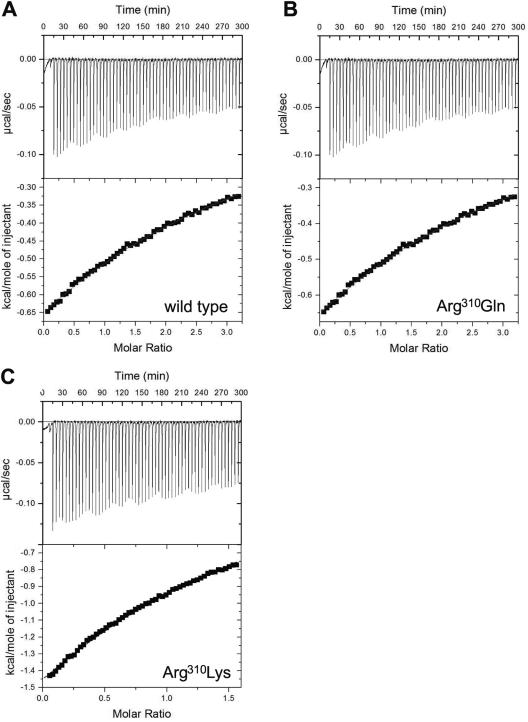

The observation of two CoA binding sites in the soaked structure was unexpected; thus, the binding of CoA to Pta in solution was examined by isothermal titration calorimetry (Fig. 4, top panel). The experimental data could not be modeled with a single binding site (Fig. 4, middle panel); however, a significant improvement in the data fit was obtained by assuming that there are two sequential and independent binding sites (Fig. 4, bottom panel). One binding site was characterized by a dissociation constant of ∼20 μM and an associated enthalpy of about 10 kcal/mol. The other site displayed a dissociation constant of approximately 1 mM, but the enthalpy could not be accurately determined. Both binding events were characterized by negligible entropic contributions. Based on interactions observed in the cocrystallized and soaked structures, it can be assumed that the higher-affinity binding site corresponds to CoA1 and the lower-affinity site corresponds to CoA2. Despite its lower binding affinity, the CoA2 site must have functional relevance for the enzyme since site-specific replacement of either Arg87 or Arg133 led to a considerable increase in the Km for CoA (12). One possible explanation for this observation is that these two residues preorient the CoA molecule before it is transferred into the high-affinity binding site, where catalysis occurs. Analysis of the CoA1 and CoA2 sites suggests that CoA1 binds at the site of catalysis; thus, for further mechanistic interpretations we focused on the CoA1 position.

FIG. 4.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of CoA binding to Pta. The raw data are shown in the top panel. The middle panel shows an attempt to fit the data to a single binding site model (solid line). The bottom panel shows the data fit to two independent binding sites, and the curve precisely coincides with the experimental data points.

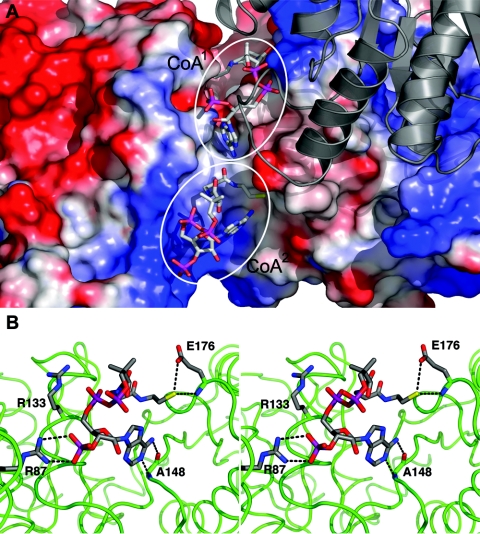

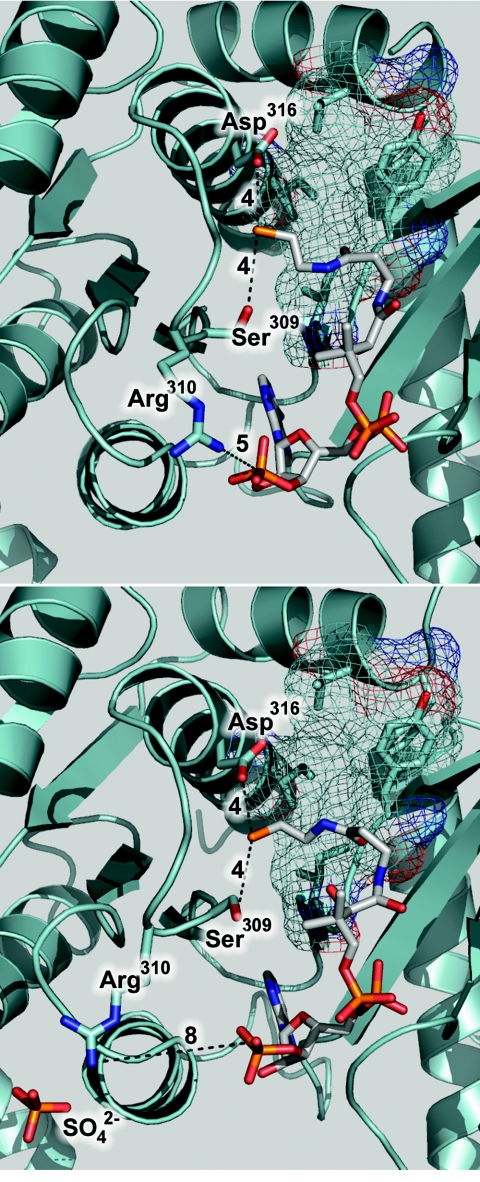

The identification of CoA1 as the catalytically relevant site is based on several convergent lines of reasoning. The CoA1 site is occupied in at least one monomer of both structures described here, and CoA1 interacts more extensively with Pta than CoA2 interacts with Pta. Furthermore, the CoA1 site is located in the most highly conserved region of the proposed active site cleft (13). Although CoA2 interacts with Arg87 and Arg133, residues previously shown to be important for binding CoA (12), the reactive sulfhydryl of CoA2 is pointed out toward the solvent (Fig. 3B). The reactive sulfhydryl group of CoA1, however, is located in the active site cleft proximal to residues either implicated in catalysis or predicted to be present in the active site. The guanidino group of Arg310 is located 5 Å and 8 Å from the 3′ phosphate of CoA1 in the cocrystallized and soaked structures (Fig. 5). In the soaked structure, Arg310 was found to coordinate a sulfate ion originating from the mother liquor. The interaction with the sulfate ion in the soaked structure orients Arg310 differently relative to its position in the cocrystallized structure, demonstrating the mobility of this residue. In a previous study, replacement of Arg310 with a glutamine was found to decrease the kcat 62-fold compared to wild-type Pta, suggesting that Arg310 has a function in catalysis (31). Cys312, which is located 2 Å and 3.5 Å from the −SH of CoA1 in the cocrystallized and soaked structures, was predicted to be present in the active site based on modification of this residue and inhibition of activity by N-ethylmaleimide, which could be alleviated by preincubation with substrates (31). This result is also consistent with previous reports that the activity of other Ptas can be affected by thiol-modifying reagents (9, 34). These results indicate that CoA1 binds at the probable catalytic site, and based on a closer inspection of the enzyme architecture surrounding CoA1 we identified Ser309 and Asp316 in addition to Arg310 as potential catalytic residues to target for functional analyses (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Location of residues targeted for replacement. (Top panel) Architecture surrounding the −SH of CoA1 in monomer A of the cocrystallized structure. (Bottom panel) Architecture surrounding the −SH of CoA1 in monomer A of the soaked structure. In both panels, residues targeted for replacement are labeled and indicated by sticks. Key distances (in angstroms) discussed in the text are indicated by dashed lines. Residues comprising a hydrophobic pocket near the −SH of CoA1 are indicated by unlabeled sticks, and the surface of the pocket is indicated by a mesh. The sulfate ion coordinated by Arg310 in the soaked structure is shown in a stick representation.

Proposed role for Arg310.

Arg310 is strictly conserved in an alignment of 32 Pta sequences (13), and it has been proposed that this residue plays a role in catalysis based on kinetic analyses of an Arg310Gln variant (31). Furthermore, different orientations of the side chain observed in the structures presented here suggest that its conformational flexibility may play a role in positioning one or both substrates. To address the function of Arg310, the kinetic parameters of Arg310Ala, Arg310Gln, and Arg310Lys variants were determined. The variants had kcat values that were lower than the value for wild-type Pta (Table 5), further supporting the hypothesis that this residue has a catalytic role. A previous mechanistic analysis of the C. kluyveri Pta suggested that a residue with a pKa of >9 may polarize the carbonyl group of acetyl phosphate and make it more susceptible to nucleophilic attack (19). This is one potential role for Arg310, and in this case a lysine residue should be able to substitute for this function; however, the Arg310Lys variant had the lowest kcat. Another possible function for Arg310 is to orient one or both substrates for optimal nucleophilic attack via bidentate interactions with the phosphate groups. If Arg310 also has this function, the greater steric bulk of glutamine or lysine compared to alanine may have interfered with the proper positioning and could account for the more profound decreases in kcat observed for the Arg310Gln and Arg310Lys variants. If the positively charged Arg310 guanidino group binds the phosphate groups of either substrate in a bidentate manner, the positive charge at position 310 in the Arg310Lys variant may substitute for binding but force the substrate into a catalytically incompetent orientation, explaining why this variant had the lowest kcat.

TABLE 5.

Kinetic parameters of wild-type and variant phosphotransacetylases

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | Km (CoA) (μM) | kcat/Km (CoA) (μM−1 s−1) | Km (AcP) (μM)a | kcat/Km (AcP) (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 5,190 ± 30 | 65 ± 7 | 80 ± 9 | 185 ± 6 | 28 ± 1 |

| Ser309Ala | 14.5 ± 0.4 | 67 ± 8 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 94 ± 8 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| Ser309Cys | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 94 ± 15 | 0.065 ± 0.011 | 255 ± 32 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| Ser309Thr | 15.4 ± 0.6 | 37 ± 5 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 175 ± 15 | 0.088 ± 0.008 |

| Arg310Ala | 230 ± 20 | 120 ± 27 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 22,500 ± 6,400 | 0.01 ± 0.003 |

| Arg310Gln | 69 ± 4 | 185 ± 18 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 775 ± 99 | 0.1 ± 0.009 |

| Arg310Lys | 11.0 ± 0.4 | 116 ± 13 | 0.095 ± 0.011 | 531 ± 35 | 0.021 ± 0.002 |

| Asp316Glu | 2,150 ± 30 | 74 ± 13 | 29 ± 5 | 143 ± 11 | 15 ± 1 |

AcP, acetyl phosphate.

Although the side chain of Arg310 is near the 3′ phosphate of CoA1 (Fig. 5), only modest increases in the Km values for CoA were observed for each of the variants, arguing against a role for Arg310 in the interaction with CoA. The Km values for acetyl phosphate, however, were greater than the value for the wild type (Table 5), which is consistent with a role for Arg310 in the interaction with this substrate. Therefore, the binding of acetyl phosphate to wild-type Pta and Arg310 variants was examined by isothermal titration calorimetry. The titration curve for each enzyme fit an equation describing a single binding site per monomer (Fig. 6). The corresponding KD values were very similar to the Km values and indicated that the binding of acetyl phosphate to Pta is an enthalpically driven process with minimal entropic contributions (Table 6). The binding to wild-type Pta was predictably the most energetically favorable binding (ΔG = −5.1 kcal mol−1), followed by binding to the Arg310Gln variant (ΔG = −4.3 kcal mol−1) and the Arg310Lys variant (ΔG = −4.1 kcal mol−1). Binding of acetyl phosphate to Arg310Ala could not be detected by isothermal titration calorimetry, consistent with the large Km value observed for this variant. The profound increase in the Km for acetyl phosphate and the inability to calorimetrically detect acetyl phosphate binding to the Arg310Ala variant support the hypothesis that Arg310 has a role in binding this substrate. The Km for acetyl phosphate observed for the Arg310Lys variant was 42-fold lower than the Km for the Arg310Ala variant, implying that a positive charge at this position is important for acetyl phosphate binding. However, the Arg310Lys variant had Km and KD values for acetyl phosphate that were threefold and sixfold higher than the values for the wild type, suggesting that the bidentate charge of arginine may be necessary to properly bind the substrate.

FIG. 6.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of acetyl phosphate binding to Pta. (A) Wild type. (B) Arg310Gln. (C) Arg310Lys. In each case the raw data are shown in the top panel, and the data fit to a single-binding-site model is shown in the bottom panel.

TABLE 6.

Thermodynamic parameters of acetyl phosphate binding to wild-type and variant phosphotransacetylases

| Enzyme | na | KD (μM) | ΔH (kcal mol−1) | ΔG (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1 | 180 ± 10 | −8.1 ± 0.2 | −5.1 |

| Arg310Gln | 1 | 670 ± 20 | −12.0 ± 3 | −4.3 |

| Arg310Lys | 1 | 1,010 ± 20 | −10.0 ± 0.1 | −4.1 |

The values extracted from the data sets for “n” ranged from 0.8 to 1.3 and were fixed at 1 for consistent curve fitting.

Together, the kinetic and calorimetric data support the hypothesis that Arg310 has roles in facilitating catalysis and also binding acetyl phosphate. We propose that Arg310 binds acetyl phosphate via a bidentate interaction of its positively charged guanidino side chain with the phosphate dianion moiety of acetyl phosphate. In both structures described here, Arg310 is oriented with its side chain pointed away from the active site cleft; however, this residue is located on a flexible loop of the protein, and rotation about the backbone would orient the side chain toward the active site cleft close to the reactive sulfhydryl of CoA1. A hydrophobic pocket formed by highly conserved hydrophobic residues (Phe4, Leu5, Phe294, Ile297, and Ile323) previously identified in the apo-Pta structure (13) is located in the vicinity of the reactive sulfhydryl of CoA1 (Fig. 5). This pocket is spatially positioned to accept the methyl group of acetyl phosphate and would place the scissile bond of acetyl phosphate adjacent to the sulfhydryl of CoA1. The methyl group would presumably have some mobility within the hydrophobic pocket, and Arg310 may facilitate catalysis by optimizing the position of acetyl phosphate and polarizing the carbonyl group for nucleophilic attack by CoA1.

Proposed role for Ser309.

Ser309 is also strictly conserved in the alignment of 32 Pta sequences (13) and is located 4 Å from the sulfhydryl group of CoA1; thus, Ser309 was targeted for site-specific replacement to determine if this residue participates in catalysis. The variants had kcat values that were greatly decreased relative to the value for the wild type, while the relative differences in the Km values were only minor for both substrates (Table 5). These results indicate that Ser309 is essential for catalysis and does not participate in substrate binding. One possible catalytic role for Ser309 is to act as a nucleophile in a ping-pong mechanism; however, all previously described kinetic analyses of Ptas suggested that the mechanism proceeds through formation of a ternary complex (20, 28), and attempts to isolate an acetyl-Pta intermediate were unsuccessful (9).

Carnitine acetyltransferase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase catalyze base-facilitated transfers of an acetyl group between CoA and carnitine or chloramphenicol, analogous to the acetyl transfer catalyzed by Pta. For each of these enzymes, a serine has been proposed to function as a hydrogen bond donor to stabilize the negatively charged transition state of the reaction (23, 41). The kinetic data for the Ser309 variants are consistent with a similar role for Ser309 in stabilizing the transition state of the reaction catalyzed by Pta. The inability of threonine or cysteine to substitute for serine in this role was unexpected but not inexplicable. It was expected that the −SH side chain of cysteine could also serve as a hydrogen bond donor; however, if the side chain of the Ser309Cys variant were deprotonated in the enzyme active site, this residue would be unable to function in this role. While the −OH side chain of the Ser309Thr variant would certainly be protonated, steric constraints could prevent threonine from substituting for serine in catalysis.

Proposed role for Asp316.

The mechanism of Ptas from several species has been proposed to proceed via a concerted attack on the carbonyl carbon of acetyl phosphate by CoA, rather than via a ping-pong mechanism involving an acetyl-enzyme intermediate (9, 10, 19, 20, 28). The results of steady-state kinetic studies of the M. thermophila Pta also support a concerted mechanism (22a). The pKa of the −SH proton of free CoA is 9.6 (2); thus, a base would be required at physiological pH to remove the proton and generate the nucleophilic thiolate anion of CoA. It was previously estimated that a base performing this function in Pta would have a pKa of <6 (19). Inspection of the CoA1 site in the M. thermophila Pta structures described here revealed an aspartate (Asp316) that is perfectly conserved in the alignment of 32 Pta sequences (13) and is located 4 Å from the reactive −SH in both structures (Fig. 5). Asp316 is proposed to function as the catalytic base, and an Asp316Glu variant had a kcat that was lower than the value for the wild type with minimal impact on the Km for either substrate (Table 5). This result is consistent with the proposed role for Asp316; however, attempts to produce Asp316Ala, Asp316Leu, and Asp316Asn variants in E. coli resulted in insoluble proteins, which precluded a firm conclusion that supported the proposed role.

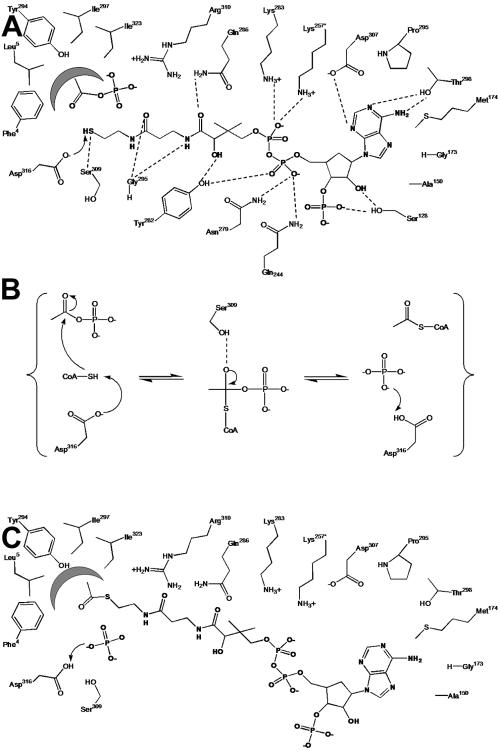

Proposed catalytic mechanism for Pta.

The reaction mechanism shown in Fig. 7 is consistent with mechanistic and kinetic results for Ptas obtained to date and additionally takes into account the architecture of the active site of the enzyme deduced from the structures described here, as well as the results of kinetic analyses of site-specific replacement variants. Acetyl phosphate is proposed to bind to the active site of Pta with its phosphate group coordinated by the catalytically essential residue Arg310 and its methyl group located in the hydrophobic pocket formed by Phe4, Leu5, Phe294, Ile297, and Ile323. In Fig. 7 CoA is shown in its catalytically relevant orientation (CoA1 site) with the adenine ring located in a pocket formed by Ser128, Ala150, Gly173, Pro296, and Asp307, and hydrogen bonds between CoA1 and the protein are indicated. The proposed mechanism proceeds through base-facilitated catalysis, with Asp316 abstracting the sulfhydryl proton from CoA1, enabling the thiolate anion to directly attack the carbonyl carbon of acetyl phosphate (Fig. 7A). This mechanism involves the formation of a negatively charged transition state that could theoretically be stabilized by Ser309 (Fig. 7B). Once acetyl-CoA has been formed (Fig. 7C), the resulting PO43− ion abstracts the proton from Asp316, balancing one of the negative charges of the phosphate to make it a better leaving group and returning Asp316 to a deprotonated state for another round of catalysis. A similar mechanism has been proposed for carnitine and chloramphenicol acetyltransferases, which catalyze analogous reactions (23, 41).

FIG. 7.

Proposed mechanism of the reaction catalyzed by Pta. (A) Substrates bound in the active site. (B) Stabilization of the negatively charged transition state. (C) Products bound in the active site. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds inferred from the crystal structures; residues Lys257 and Gln244 originate from the adjacent monomer; and the arrows indicate electron flow as discussed in the text. The figure was generated with ChemDraw Ultra (3).

Conclusions.

In summary, this study was the first investigation of a Pta to incorporate mechanistic analyses with structural information and to propose a model of catalysis consistent with the results of previous kinetic analyses (9, 10, 39). Analysis of the crystal structures of M. thermophila Pta in complex with CoA allowed us to identify the active site of the enzyme, to ascertain which residues are in reasonable proximity to participate in catalysis, and to analyze and propose functions for these residues. Kinetic studies of Pta variants have identified Ser309 as a catalytically essential residue in the Pta active site and have clarified the role of Arg310 interacting with acetyl phosphate. Furthermore, the structural analysis indicated that Asp316 is present in the active site and could participate in catalysis. The different conformations of monomers observed in the Pta structures raise intriguing questions about the impact that domain movements may have on catalysis. The apparent closure of the active site cleft could position the substrates and residues for catalysis or could exclude water from the active site, preventing abortive hydrolysis of acetyl phosphate. The true functional relevance of the CoA2 site is unknown. This site may be either a loading site to preorient CoA or a regulatory site to control Pta activity, although the measured KD for this binding site (1 mM) may be greater than the concentration of CoA available in the cell. While no data are available for a Methanosarcina species, intracellular CoA concentrations ranging from 180 to 860 μM have been reported for other archaea (11). While much information was derived from the results described here, additional structural and kinetic data are required to address these outstanding questions and to confirm the proposed mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grants GM44661-09 to J.G.F. and DK54835 to H.S.

We are indebted to the late Robert T. Simpson for use of his analytical ultracentrifuge and assistance with data interpretation, and we thank Steven J. Benkovic for use of his isothermal titration calorimeter, Allen T. Phillips for insightful comments and advice, and Jennifer A. Doebbler for collection of the high-resolution data set.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbieri, J. T., and C. D. Cox. 1979. Pyruvate oxidation by Treponema pallidum. Infect. Immun. 25:157-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budavari, S. (ed.). 1989. The Merck index, 11th ed. Merck and Co., Rahway, NJ.

- 3.CambridgeSoft. 2000. CS ChemDraw Ultra, 6.0 ed. CambridgeSoft Corporation, Cambridge, MA.

- 4.Chang, D. E., S. Shin, J. S. Rhee, and J. G. Pan. 1999. Acetate metabolism in a pta mutant of Escherichia coli W3110: importance of maintaining acetyl coenzyme A flux for growth and survival. J. Bacteriol. 181:6656-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLano, W. L., and J. W. Lam. 2005. PyMOL, 0.98 ed. DeLano Scientific LLC, South San Francisco, CA.

- 6.Drake, H. L., S. I. Hu, and H. G. Wood. 1981. Purification of five components from Clostridium thermoaceticum which catalyze synthesis of acetate from pyruvate and methyltetrahydrofolate. Properties of phosphotransacetylase. J. Biol. Chem. 256:11137-11144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferry, J. G. 1993. Fermentation of acetate, p. 304-334. In J. G. Ferry (ed.), Methanogenesis: ecology, physiology, biochemistry & genetics. Chapman & Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Gerstmeir, R., A. Cramer, P. Dangel, S. Schaffer, and B. J. Eikmanns. 2004. RamB, a novel transcriptional regulator of genes involved in acetate metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 186:2798-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henkin, J., and R. H. Abeles. 1976. Evidence against an acyl-enzyme intermediate in the reaction catalyzed by clostridial phosphotransacetylase. Biochemistry 15:3472-3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibbert, F., S. A. Kyrtopoulos, and D. P. Satchell. 1971. Kinetic studies with phosphotransacetylase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 242:39-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hummel, C. S., K. M. Lancaster, and E. J. Crane III. 2005. Determination of coenzyme A levels in Pyrococcus furiosus and other archaea: implications for a general role for coenzyme A in thermophiles. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 252:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer, P. P., and J. G. Ferry. 2001. Role of arginines in coenzyme A binding and catalysis by the phosphotransacetylase from Methanosarcina thermophila. J. Bacteriol. 183:4244-4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyer, P. P., S. H. Lawrence, K. B. Luther, K. R. Rajashankar, H. P. Yennawar, J. G. Ferry, and H. Schindelin. 2004. Crystal structure of phosphotransacetylase from the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. Structure 12:559-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iyer, P. P., S. H. Lawrence, H. P. Yennawar, and J. G. Ferry. 2003. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of phosphotransacetylase from Methanosarcina thermophila. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59:1517-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jablonski, P. E., A. A. DiMarco, T. A. Bobik, M. C. Cabell, and J. G. Ferry. 1990. Protein content and enzyme activities in methanol- and acetate-grown Methanosarcina thermophila. J. Bacteriol. 172:1271-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, M. L., J. J. Correia, D. A. Yphantis, and H. R. Halvorson. 1981. Analysis of data from the analytical ultracentrifuge by nonlinear least-squares techniques. Biophys. J. 36:575-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakuda, H., K. Shiroishi, K. Hosono, and S. Ichihara. 1994. Construction of Pta-Ack pathway deletion mutants of Escherichia coli and characteristic growth profiles of the mutants in a rich medium. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 58:2232-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunkel, T. A., J. D. Roberts, and R. A. Zakour. 1987. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 154:367-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyrtopoulos, S. A., and D. P. Satchell. 1972. Kinetic studies with phosphotransacetylase. III. The acylation of phosphate ions by acetyl coenzyme A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 276:376-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyrtopoulos, S. A., and D. P. Satchell. 1972. Kinetic studies with phosphotransacetylase. IV. Inhibition by products. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 276:383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. McArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structres. J. Applied Crystallogr. 26:283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latimer, M. T., and J. G. Ferry. 1993. Cloning, sequence analysis, and hyperexpression of the genes encoding phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase from Methanosarcina thermophila. J. Bacteriol. 175:6822-6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Lawrence, S. H., and J. G. Ferry. 2006. Steady-state kinetic analysis of phosphotransacetylase from Methanosarcina thermophila. J. Bacteriol. 188:1155-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewendon, A., I. A. Murray, W. V. Shaw, M. R. Gibbs, and A. G. Leslie. 1990. Evidence for transition-state stabilization by serine-148 in the catalytic mechanism of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase. Biochemistry 29:2075-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundie, L. L., Jr., and J. G. Ferry. 1989. Activation of acetate by Methanosarcina thermophila. Purification and characterization of phosphotransacetylase. J. Biol. Chem. 264:18392-18396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenney, D., and T. Melton. 1986. Isolation and characterization of ack and pta mutations in Azotobacter vinelandii affecting acetate-glucose diauxie. J. Bacteriol. 165:6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov, G. N., A. A. Vagin, A. Lebedev, K. S. Wilson, and E. J. Dodson. 1999. Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55:247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pascal, M. C., M. Chippaux, A. Abou-Jaoude, H. P. Blaschkowski, and J. Knappe. 1981. Mutants of Escherichia coli K12 with defects in anaerobic pyruvate metabolism. J. Gen. Microbiol. 124:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelroy, R. A., and H. R. Whiteley. 1972. Kinetic properties of phosphotransacetylase from Veillonella alcalescens. J. Bacteriol. 111:47-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perrakis, A., R. Morris, and V. S. Lamzin. 1999. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:458-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phue, J. N., and J. Shiloach. 2004. Transcription levels of key metabolic genes are the cause for different glucose utilization pathways in E. coli B (BL21) and E. coli K (JM109). J. Biotechnol. 109:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasche, M. E., K. S. Smith, and J. G. Ferry. 1997. Identification of cysteine and arginine residues essential for the phosphotransacetylase from Methanosarcina thermophila. J. Bacteriol. 179:7712-7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhie, H. G., and D. Dennis. 1995. The function of ackA and pta genes is necessary for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) synthesis in recombinant pha+ Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 41(Suppl. 1):200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu, M., T. Suzuki, K. Y. Kameda, and Y. Abiko. 1969. Phosphotransacetylase of Escherichia coli B, purification and properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 191:550-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sotirios, A., S. A. Kyrtopoulos, and D. P. Satchell. 1974. Thiol-blocking reagents and phosphate acetyltransferase catalysis, and the assessment of protection by adsorbed molecules. Biochem. J. 141:905-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadtman, E. R. 1952. The purification and properties of phosphotransacetylase. J. Biol. Chem. 196:527-534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vagin, A., and A. Teplyakov. 2000. An approach to multi-copy search in molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56:1622-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wanner, B. L., and M. R. Wilmes-Riesenberg. 1992. Involvement of phosphotransacetylase, acetate kinase, and acetyl phosphate synthesis in control of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:2124-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whiteley, H. R., and R. A. Pelroy. 1972. Purification and properties of phosphotransacetylase from Veillonella alcalescens. J. Biol. Chem. 247:1911-1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiseman, T., S. Williston, J. F. Brandts, and L. N. Lin. 1989. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem. 179:131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, D., L. Govindasamy, W. Lian, Y. Gu, T. Kukar, M. Agbandje-McKenna, and R. McKenna. 2003. Structure of human carnitine acetyltransferase. Molecular basis for fatty acyl transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 278:13159-13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu, Q. S., D. H. Shin, R. Pufan, H. Yokota, R. Kim, and S. H. Kim. 2004. Crystal structure of a phosphotransacetylase from Streptococcus pyogenes. Proteins 55:479-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]