Abstract

The PROSITE database consists of a large collection of biologically meaningful signatures that are described as patterns or profiles. Each signature is linked to a documentation that provides useful biological information on the protein family, domain or functional site identified by the signature. The PROSITE database is now complemented by a series of rules that can give more precise information about specific residues. During the last 2 years, the documentation and the ScanProsite web pages were redesigned to add more functionalities. The latest version of PROSITE (release 19.11 of September 27, 2005) contains 1329 patterns and 552 profile entries. Over the past 2 years more than 200 domains have been added, and now 52% of UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot entries (release 48.1 of September 27, 2005) have a cross-reference to a PROSITE entry. The database is accessible at http://www.expasy.org/prosite/.

INTRODUCTION

The PROSITE database uses two kinds of signatures or descriptors to identify conserved regions, i.e. patterns and generalized profiles, which both have their own strengths and weaknesses defining their area of optimum application. Each PROSITE signature is linked to an annotation document where the user can find information on the protein family or domain detected by the signature: origin of its name, taxonomic occurrence, domain architecture, function, 3D structure, main characteristics of the sequence, domain size and some references. As a more detailed description of the PROSITE database has already been provided in previous publications (1,2), this paper will only focus on recent developments that have taken place during the last 2 years.

AUTOMATED UPDATE OF PATTERNS

Patterns or regular expressions are useful tools to identify short and well-conserved regions, such as catalytic sites, binding sites, post-transcriptional modifications (PTMs) or zinc fingers. They are also easy to construct and to use by biologists that have no knowledge in bioinformatics. But patterns do not stand the test of time very well. If a new sequence has an amino acid at a conserved position that was not present in the seed alignment used to construct the pattern, it will not be recognized. Thus, patterns need to be updated regularly to introduce this new variability in the regular expression.

We have developed a tool to identify weak patterns and automatically update them. This tool uses the PROSITE match list, which stores true positives, false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), partial and unknown matches, to generate a new pattern that minimizes FP and FN.

FP and FN updates are treated independently. We first take care of FN in a three-step procedure:

The patterns that can potentially be updated are selected. Updating a pattern to recover FN amounts to introduce more variability in the pattern, but it increases the risk of creating new FP. Hence, only patterns that are stringent enough can be updated. The selection procedure consists of running all PROSITE patterns on a random database to keep only the ones that do not produce too many matches.

Mismatches produced by each FN are detected and the pattern is modified accordingly to accept the observed residues.

The new pattern is tested on a random database to see whether it is still stringent enough. If it produces too many matches in a random database, the pattern is refined and some mismatch positions are removed.

To remove false positives we check ‘wildcard’ positions (‘x’ with the PROSITE syntax) in the pattern. We look at these positions for amino acids that are only found in FP sequences. These amino acids are then ‘forbidden’ ({} with the PROSITE syntax) at these positions in the new pattern.

The new pattern is then used to scan Swiss-Prot and all new matches are checked manually. Only patterns that produce no new false positives are kept.

This strategy has allowed the automatic update of 943 patterns (out of a total of 1322 patterns in PROSITE). 2661 FN (out of a total of 14 412) and 1927 FP (out of a total of 7446) were removed. We have also removed the less specific patterns that could not be updated and have replaced them by profiles. The application of these two strategies allowed a decrease of the number of FP and FN in the Swiss-Prot part of UniProt by ∼25%. The procedure to automatically update patterns is run at each major release.

NEW FUNCTIONAL PREDICTION TOOL

When a signature identifies a conserved region in a given protein, it is important to know what functional information can be transferred to this new protein according to what is known about the function of the conserved region. If the information that is transferred is very general (name and position of a given domain in a sequence) only the occurrence of a match with a descriptor at a reliable score is enough. But descriptors can supply much more precise information. If one looks at the residue level, functional sites such as active sites, disulfide bridges or PTM sites can be identified. One can also look at the domain arrangement to discriminate between particular families or sub-families. The predicted function of the protein can thus be much more accurate.

PROSITE has a long experience in documentation and detailed annotation of domains, families and functional sites. This information is mainly stored in free text and used by biologists who read the various documents and make their own decision on the function of their protein according to the PROSITE matches. But with the rapid growth of sequence databases, there is an increasing need for a reliable tool that can generate automatically precise and accurate functional annotation in standard format. We thus decided to group some functional information stored in PROSITE in a database of rules that can easily be read by a program and applied on proteins that are recognized by PROSITE profiles. We named this complementary database ProRule, for PROSITE rules. ProRule generates annotation in Swiss-Prot format for DE, CC, KW or FT lines.

Two types of information are stored in ProRule:

General information: the occurrence of a match with a profile is enough to trigger this annotation. Usually, it is restricted to the name of the domain and the position of its boundaries.

Conditional information: this is dependent on the presence of given amino acids at precise positions, on the occurrence of other domains or on taxonomic specificity. This information is only transferred if the conditions are fulfilled. For example, an enzymatic active site is annotated only if the correct amino acid is found at the required position.

ProRule is extensively used by Swiss-Prot curators to facilitate the annotation work and to check the consistency of Swiss-Prot entries. But it can also be accessible for external users through the ScanProsite web page (see below) or downloaded from the PROSITE ftp site under PROSITE license conditions. For more details on ProRule and its range of application see Sigrist et al. (3).

WEB PAGE

The PROSITE website was redesigned and new predictive tools were implemented to assign more detailed functional information to the scanned proteins. Users who want to scan their own proteins against all PROSITE entries or to scan a PROSITE entry against a protein database will find a new version of the ScanProsite web page.

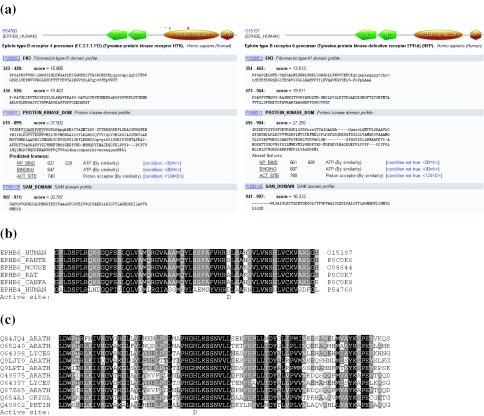

PROSITE matches on UniProt knowledgebase (UniProtKB) or PDB entries are now pre-calculated and stored in a relational database (PostgreSQL) that is maintained in collaboration with Swiss-Prot (4). This greatly speeds up the scanning of UniProtKB proteins. A domain visualizer was integrated in the result page (see Figure 1a). Each ProRule associated with a PROSITE profile is also scanned, which allows the localization of interesting functional residues such as active sites, PTMs and disulfide bridges. These features are only shown if the expected amino acid is found at the right position. But we also indicate missing features when we expect another amino acid at a given position. This tool can be used to identify divergent subfamilies of proteins like inactive enzymes. In Figure 1a, we show the ScanProsite output for the human ephrin B4 receptor, which is a functional kinase receptor (5), and its paralogue the ephrin B6 receptor, which is known to have an inactive kinase domain (6). The ScanProsite output indicates that the expected Asp residue was not found at the position of the active site in ephrin B6 receptor. To test the efficiency of the method, we looked at mammalian homologues of ephrin B6 receptor. We used ScanProsite to identify all mammalian homologues of the ephrin B6 receptor and to construct a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of this subfamily (Figure 1b). The MSA also shows that the conserved Asp residue of the active site is found in none of the ephrin B6 receptor orthologues. ScanProsite can also be used to identify new uncharacterized subfamilies of putatively inactive enzymes (Figure 1c). From the ScanProsite web page, we have searched with the kinase profile (PS50011) for plant proteins that have no detected active site and a common domain arrangement. We have identified an uncharacterized family of putatively inactive kinases, which is conserved in various plant genomes as it is shown in the MSA.

Figure 1.

Output of the ScanProsite web page. (a) The left protein is a classical ephrin receptor protein (ephrin B4 receptor protein) which is known to transduce a signal through its kinase domain (5). The right protein is also an ephrin receptor protein (human ephrin B6 receptor protein) but with an inactive kinase domain (6). The ProRule associated with the kinase domain identifies an active site in ephrin B4 receptor but not in ephrin B6 receptor (absent feature: active site). The canonical Asp residue at the active site position is replaced by a serine. (b) We used ScanProsite to identify orthologues of the ephrin B6 receptor in mammals, searching for proteins that have the same domain arrangement and have a putative inactive kinase domain. (c) We also identified with ScanProsite an uncharacterized plant subfamily of kinase receptors with a putative inactive kinase domain. The canonical aspartate residue at the active site position is replaced by a histidine. This kinase subfamily is conserved in various plant genomes. Both multiple sequence alignments were generated on the ScanProsite web page using the alignment with the kinase profile (PS50011).

The documentation page has also been reorganized. It now contains three main sections:

The description part that exposes the main characteristics of the domain or the family and a representative list of proteins that contain the domain or belong to the family.

A technical section that refers to the descriptors used to identify the domain or family. For each descriptor, there is a link to a domain architecture view of UniProtKB proteins matched by the descriptor, an MSA in different formats, a link to retrieve the list of proteins matched by the descriptor in various formats and a link to a taxonomy tree view of all entries containing the domain. There is also an external link to MSDsite (7) to view ligand binding statistics of the domain and a link to 3D structures.

The third section is the reference block where, for each reference, we added the PubMed ID and a direct link to the article.

The architecture view of PROSITE profiles is now visible, from each UniProtKB entry on the ExPASy server, from the PROSITE documentation page and from the ScanProsite web page. In each view, some interesting residues are tagged according to ProRule predictions (see Figure 1a).

IMPROVEMENT OF THE PROFILE METHOD CONSTRUCTION

There are currently several tools to construct efficient profiles based on MSA (8). All these tools were designed to recover very divergent proteins (<20% of similarity). They were developed 10 years ago when protein databases were quite small and very few representative genomes were sequenced. There was thus a strong sample bias when constructing seed alignments and profile tools that used these seeds needed to be strongly predictive. Currently, proteins databases are 10 times bigger and thousands of genomes have been sequenced spanning the whole tree of life. It is now easier to have a seed alignment with representatives of all possible variability and descriptors can be more conservative. There is rather an increasing need for more specific descriptors in order to have more precise functional information. As we described previously, specific annotation can be assigned to a match with a profile when looking in the matched region at the residue level for the presence of particular amino acids at particular sites, such as enzymatic active sites, disulphide bridges, etc. We thus have developed a new strategy to annotate the MSA at these particular sites and to transfer this information to the profile builder program. Profile builder parameters can then be adjusted according to the annotation. We have used this strategy to adjust specific parameters in a column-dependant manner. We have tested the weight of the matrix, gap and insertion penalties. The tool aim is to be more stringent on specific columns and to produce a better local alignment, which then helps to re-localize the functional residues in sequences matched by the profile.

HOW TO OBTAIN PROSITE

PROSITE and ProRule are freely available to academic users. As of release 16, the documentation entries of PROSITE are copyright. The ProRule database is also copyright. To obtain a license, commercial users should contact:

The Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics by email: license@isb-sib.ch or its commercial representative: Geneva Bioinformatics (GeneBio) S.A, Case Postale 210, CH-1211 Geneva 12, Switzerland, Tel: +41 22 702 99 00, Fax: +41 22 702 99 99, Email: info@genebio.com.

Weekly updates of PROSITE are available on our FTP server: ftp://ftp.expasy.org/databases/prosite/release_with_updates/.

PROSITE is also accessible from the Hits page: http://hits.isb-sib.ch/.

Frame-tolerant scans can be performed at the following address: http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/software/PFRAMESCAN_form.html.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Tania Lima for critical reading of the manuscript. PROSITE is supported by grant no. 3152A0-103922/1 from the Swiss National Science Foundation. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the State Secretariat for Education and Research (SER) of the Swiss Confederation.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sigrist C.J.A., Cerutti L., Hulo N., Gattiker A., Falquet L., Pagni M., Bairoch A., Bucher P. PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief. Bioinform. 2002;3:265–274. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulo N., Sigrist C.J.A., Le Saux V., Langendijk-Genevaux P.S., Bordoli L., Gattiker A., De Castro E., Bucher P., Bairoch A. Recent improvements to the PROSITE database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:134–137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigrist C.J.A., De Castro E., Langendijk-Genevaux P.S., Le Saux V., Bairoch A., Hulo N. ProRule: a new database containing functional and structural information on PROSITE profiles. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4060–4066. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattiker A., Michoud K., Rivoire C., Auchincloss A.H., Coudert E., Lima T., Kersey P., Pagni M., Sigrist C.J.A., Lachaize C., et al. Automated annotation of microbial proteomes in SWISS-PROT. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2003;27:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1476-9271(02)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kullander K., Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;7:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuoka H., Iwata N., Ito M., Shimoyama M., Nagata A., Chihara K., Takai S., Matsui T. Expression of a kinase-defective Eph-like receptor in the normal human brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:487–492. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golovin A., Dimitropoulos D., Oldfield T., Rachedi A., Henrick K. MSDsite: a database search and retrieval system for the analysis and viewing of bound ligands and active sites. Proteins. 2005;58:190–199. doi: 10.1002/prot.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmann K. Sensitive protein comparisons with profiles and hidden Markov models. Brief. Bioinform. 2000;2:167–178. doi: 10.1093/bib/1.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]