Abstract

The Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) is an online resource (http://smart.embl.de/) used for protein domain identification and the analysis of protein domain architectures. Many new features were implemented to make SMART more accessible to scientists from different fields. The new ‘Genomic’ mode in SMART makes it easy to analyze domain architectures in completely sequenced genomes. Domain annotation has been updated with a detailed taxonomic breakdown and a prediction of the catalytic activity for 50 SMART domains is now available, based on the presence of essential amino acids. Furthermore, intrinsically disordered protein regions can be identified and displayed. The network context is now displayed in the results page for more than 350 000 proteins, enabling easy analyses of domain interactions.

INTRODUCTION

When the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) database was first made public 8 years ago (1), the current extent of completely sequenced genomes was little more than a dream. In the last few years, the astonishing successes of whole organism approaches to biology are not only limited to sequencing efforts but also include techniques, such as the high-throughput identification of protein–protein interactions, which have created new opportunities and higher expectations for computational approaches to interpreting biological sequences. In the last 2 years, we have been developing new ways of meeting these challenges.

The basic data of SMART are high-quality manually derived alignments of protein domain families. As hidden Markov models (2) these allow us to identify protein domains in sequence databases; these results are stored in a database accessible via a simple web interface (http://smart.embl.de). The data provide a framework for understanding the evolution and function of genes and proteins throughout the living world. Whereas the SMART philosophy has been to include essentially all available protein sequences, we recognize that many users are interested primarily in the biology of a particular organism. Accordingly, we have developed new views more tightly integrated with genome data. These new genome views allow further cross-referencing with protein–protein interaction maps, making SMART an invaluable tool for systems biologists to interpret pathways and networks.

REDUCED PROTEIN DATABASE REDUNDANCY AND ‘GENOMIC’ MODE

Owing to the nature of our source databases (Swiss-Prot, SP-TrEMBL and Ensembl) (3,4) the protein database in SMART has significant redundancy, even though identical proteins are removed. Different proteins and fragments in the source databases often correspond to the same gene. Users exploring the various domain architectures or interested in domain counts in various genomes are particularly vulnerable to this problem, as the numbers they get are often inflated and unrealistic. To overcome this problem, we extended SMART with a new operating mode, namely ‘Genomic’ mode. The main difference between normal and genomic mode in SMART is the underlying protein database. In genomic mode, only the proteins from 170 completely sequenced genomes are included (a full list is available at http://smart.embl.de/smart/list_genomes.pl). Swiss-Prot (3) is our main source database of genomic data, together with Ensembl (4) for metazoan genomes. This database has minimal redundancy, and is therefore particularly useful for whole genome studies of domain architectures or single domain distributions.

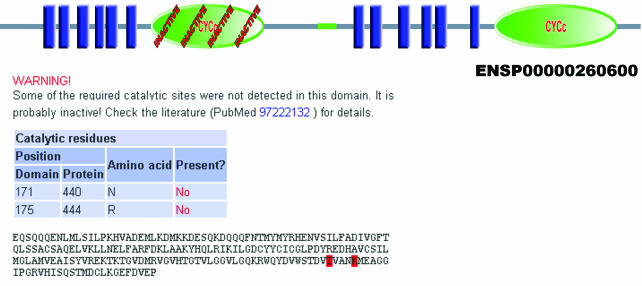

PREDICTION OF CATALYTIC ACTIVITY

To improve the function prediction for single domains, we annotated essential catalytic sites for all enzymatic domains in SMART. These were extracted from structural reports in the primary literature, wherever the catalytic mechanism was known (5). Now, protein sequences can be scanned for the presence of important catalytic amino acids (Figure 1). Absence of one of these amino acids very likely results in loss of catalytic activity. Recently, it turned out that many domains homologous to signaling enzymes seem to have lost their catalytic ability, although they are evolutionarily conserved. Instead of a catalytic function these domains appear to play a role in regulatory processes. This trend is especially obvious in the protein tyrosine phosphatase family (5). The inclusion of catalytic amino acid residues in the database will allow a more rapid identification of inactive enzyme homologs in the future.

Figure 1.

Prediction of catalytic activity in SMART. First guanylyl cyclase domain in human adenylate cyclase type III (ENSP00000260600) is marked as ‘inactive’ because the two amino acids required for its activity are not present. Domain annotation page shows which amino acids are not detected and gives pointers to the relevant literature.

DOMAIN ARCHITECTURE INVENTION DATING

As a further step from the single domain to the understanding of multi domain proteins, SMART now predicts the taxonomic class, where the concept of a protein, that is its domain architecture, was invented. The domain architecture is defined as the linear order of all SMART domains in the protein sequence. To derive the point of its invention, all proteins with the same domain architecture are mapped onto NCBIs taxonomy (6). The last common ancestor of all organisms containing at least one protein with the domain architecture is defined as the point of its origin. From the knowledge on the origin of domain architectures one might infer the distribution and presence of these architectures in not yet or incompletely sequenced genomes. In addition, conclusions on the general function of domain architectures can be drawn.

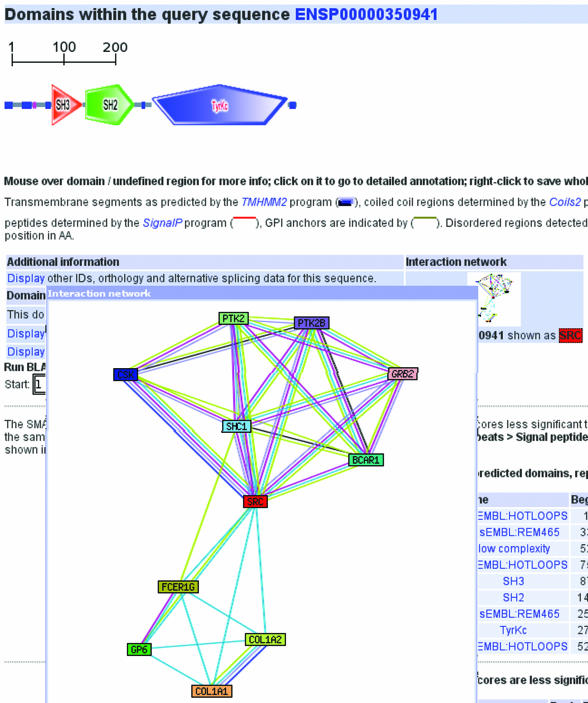

PROTEIN INTERACTION DATA

The latest version of SMART provides information about putative interaction partners for more than 350 000 proteins (Figure 2). This information is imported from the STRING database (7), in which known and predicted protein–protein associations are integrated from a variety of sources. The interactors are shown in SMART in the form of a summary graphic (network); the various types of interaction evidence are depicted as lines of different colors in the network. Clicking on the graphic will launch the STRING website, where the underlying evidence can be studied in detail. The interactions in STRING include physical binding interactions, as well as functional associations, such as membership in a common pathway or process. The data are derived from a variety of sources, including knowledge bases, such as BIND (8), KEGG (9), HPRD (10) and Reactome (11), as well as in silico prediction approaches and automated text-mining. STRING aims to improve usability of the interactome by scoring and ranking interaction data (making a confidence estimate on each prediction), as well as by transferring interaction knowledge between model organisms where applicable. SMART and STRING are both cross-referenced through a common set of proteins and genomes, and STRING in turn uses domain information from the SMART server in its pages as well.

Figure 2.

Interaction networks in SMART. Around 350 000 protein annotation pages include an interaction network in a pop-up window. Networks are linked to the STRING database (http://string.embl.de) which provides the data.

NEW DATABASE FEATURES

The core of SMART is a relational database management system (RDBMS) which stores information on SMART domains (1,12). Owing to the exponentially increasing amount of data, many parts of the database access code have been updated or completely rewritten, resulting in greatly improved response times, most noticeably in the domain architecture analysis operations.

SMART database includes the information on domain presence in all proteins in a non-redundant database, now with the added data on the catalytic activity for 50 catalytic domains. All domain architecture analysis results include this information, and domains with missing essential amino acids are overlaid with the word ‘inactive’ (Figure 1). The domain annotation page provides detailed information on which of the required amino acids are missing, and gives pointers to the relevant literature.

NEW ANALYSIS METHODS

DisEMBL [http://dis.embl.de, (13)] predictions of intrinsic protein disorder were included into SMART's analysis methods. DisEMBL is a computational tool for the prediction of disordered/unstructured regions within a protein sequence. Predictions included in SMART are based on missing coordinates in X-ray structure as defined by REMARK465 entries in PDB and the ‘Hot loops’ method. Hot loops constitute a refined subset of the standard loops/coils as defined by DSSP (14), namely, those loops with a high degree of mobility as determined from C-α temperature factors (B-factors).

USER INTERFACE IMPROVEMENTS AND TECHNICAL CHANGES

SMART's user interface was completely rewritten and is now fully compliant with the latest web standards, such as XHTML1.0 and CSS2. Users with standards-compliant web browsers can fully enjoy the extra speed and features. Owing to increasing server load, the queuing system was completely rewritten and the hardware greatly expanded resulting in a more stable operation and faster response times.

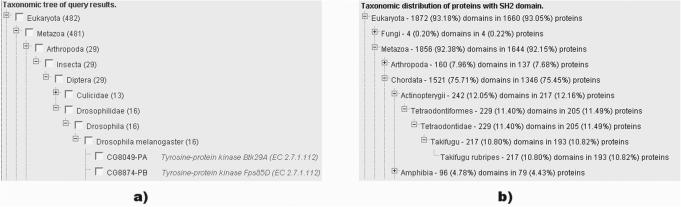

An important new feature is the introduction of taxonomic trees into SMART. Two primary uses for taxonomic trees in SMART are the grouping of domain architecture query results and the detailed taxonomic distribution of domains now shown on domain annotation pages (Figure 3). The grouping of architecture query results allows users to easily display only proteins from certain species or taxonomic nodes. Taxonomic distribution of proteins on domain annotation pages gives a detailed overview of domain presence in different species and taxa.

Figure 3.

Taxonomic trees in SMART. (a) Domain architecture query results grouped into a tree. Users can select individual proteins or taxonomic nodes to display. (b) Domain annotation pages show detailed domain and protein counts in various taxonomic nodes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Christian von Mering for providing the interaction network data and STRING links. We are grateful to Rune Linding for helping with the integration of DisEMBL predictions into SMART. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by EMBL.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schultz J., Milpetz F., Bork P., Ponting C.P. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krogh A., Brown M., Mian I.S., Sjolander K., Haussler D. Hidden Markov models in computational biology. Applications to protein modeling. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;235:1501–1531. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeckmann B., Bairoch A., Apweiler R., Blatter M.C., Estreicher A., Gasteiger E., Martin M.J., Michoud K., O'Donovan C., Phan I., et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbard T., Andrews D., Caccamo M., Cameron G., Chen Y., Clamp M., Clarke L., Coates G., Cox T., Cunningham F., et al. Ensembl 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D447–D453. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pils B., Schultz J. Inactive enzyme-homologues find new function in regulatory processes. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheeler D.L., Barrett T., Benson D.A., Bryant S.H., Canese K., Church D.M., DiCuccio M., Edgar R., Federhen S., Helmberg W., et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D39–D45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Mering C., Jensen L.J., Snel B., Hooper S.D., Krupp M., Foglierini M., Jouffre N., Huynen M.A., Bork P. STRING: known and predicted protein–protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D433–D437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfarano C., Andrade C.E., Anthony K., Bahroos N., Bajec M., Bantoft K., Betel D., Bobechko B., Boutilier K., Burgess E., et al. The Biomolecular Interaction Network Database and related tools 2005 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D418–D424. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanehisa M., Goto S., Kawashima S., Okuno Y., Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peri S., Navarro J.D., Kristiansen T.Z., Amanchy R., Surendranath V., Muthusamy B., Gandhi T.K., Chandrika K.N., Deshpande N., Suresh S., et al. Human protein reference database as a discovery resource for proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D497–D501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi-Tope G., Gillespie M., Vastrik I., D'Eustachio P., Schmidt E., de Bono B., Jassal B., Gopinath G.R., Wu G.R., Matthews L., et al. Reactome: a knowledgebase of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D428–D432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letunic I., Copley R.R., Schmidt S., Ciccarelli F.D., Doerks T., Schultz J., Ponting C.P., Bork P. SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D142–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linding R., Jensen L.J., Diella F., Bork P., Gibson T.J., Russell R.B. Protein disorder prediction: implications for structural proteomics. Structure (Camb) 2003;11:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabsch W., Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]