Abstract

The Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org/) project provides a comprehensive and integrated source of annotation of large genome sequences. Over the last year the number of genomes available from the Ensembl site has increased from 4 to 19, with the addition of the mammalian genomes of Rhesus macaque and Opossum, the chordate genome of Ciona intestinalis and the import and integration of the yeast genome. The year has also seen extensive improvements to both data analysis and presentation, with the introduction of a redesigned website, the addition of RNA gene and regulatory annotation and substantial improvements to the integration of human genome variation data.

INTRODUCTION

The genome sequence of an organism provides the natural index for organizing and understanding biological data. Ensembl provides a software system to store, analyse, use and display genomic information. The genomes of 14 chordates are currently available through Ensembl, from mammals such as Human and Mouse through to the ‘primitive’ chordate Ciona intestinalis. The genomes of three key model eukaryotes, yeast, fly and worm, are also imported from their respective databases to provide easy integration of information from these organisms with chordates. Finally a limited number of insect genomes are also available through Ensembl owing to our participation in the Vectorbase consortium.

Ensembl continues to improve both in terms of the analysis of genome information and its usability both via programmatic means and web-based browsers. This paper details the improvements since the last report (1), in particular for quality of gene structures, a new RNA gene building system, regulatory regions, comparative genomics infrastructure, data mining interfaces, web services based integration, code portability and web-based user interfaces.

RESULTS

RNA gene annotation in Ensembl

Ensembl has a traditional strength in predicting accurate and as complete as possible protein gene sets in an organism, even in the absence of direct cDNA evidence (2). This is achieved by integrating a number of lines of evidence around genes, often making use of partial cDNA or expressed sequence tag sets and similarity to protein-coding genes in other organisms. However protein-coding genes are not the only functional transcripts in a genome. There are in addition a series of functional RNA gene products from structural RNAs such as U6 RNA through to more recently discovered regulatory RNAs, such as micro RNAs (miRNAs). The Rfam resource (3) organizes all known functional RNAs into families and builds sophisticated covariance models of these sequences. We have collaborated with Rfam to provide an RNA gene build across all the Ensembl genomes, which includes both a covariance model matching step and a RNA folding estimation. The details of this method will be published in a separate paper. Table 1 shows the number of protein-coding and RNA genes predicted in a number of key organisms in Ensembl. The miRNA set is relatively constant between mammalian organisms, whereas other ncRNAs vary considerably. This is due to the high lineage specific expansion of some ncRNAs usually coupled with a high level of pseudogenes along with some functional copies.

Table 1.

Number of genes of different classes for selected species

| Species | Protein-coding genes | miRNAs | Other ncRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 22 218 | 222 | 3353 |

| Mouse | 25 613 | 221 | 1353 |

| Rat | 21 952 | 208 | 1728 |

| Dog | 18 201 | 209 | 2059 |

Variation in numbers of protein coding genes reflects different cDNA resources and genome assembly quality. For example, mouse cDNA resources contain a significant amount of unscreened repeat contamination. There is a wide variation in ncRNA numbers whereas miRNA numbers are fairly constant (see text).

Improvements to protein-coding genes

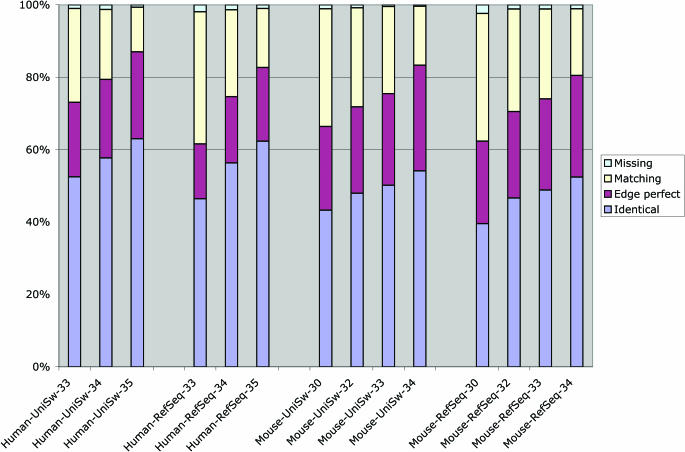

Providing as accurate as possible gene sets is one of the major goals in Ensembl. Even when there is a large amount of cDNA evidence in an organism, which is the case for both Human and Mouse, the details of how to reconcile large cDNA collections to form accurate gene sets is not trivial. This is due to the presence of large numbers of pseudogenes in mammalian genomes (4,5), the presence of truncated and chimaeric cDNAs in cDNA collections (6) and polymorphisms between the genome and cDNA collections. Figure 1 shows the increase in quality of our gene resources in Human and Mouse. These improvements are due to assembly improvements, improvements in cDNA collections, careful screening of cDNA collections for contaminations and algorithmic improvements in the gene build. The algorithmic improvements mainly come from careful parameterization of different alignment programs, in particular genewise (7) and exonerate (8), in combination with a more advanced logic of when each alignment program is appropriate. We are continuing to work in collaboration with the RefSeq group at NCBI, the Havana group at the Sanger Institute (9) and the UCSC genome group to develop a stable set of protein-coding gene structures which we agree on to the base pair. The project, called CCDS, made its first release in March 2005, identifying 14 795 transcripts in 13 142 genes which all groups agree on. These are labelled with CCDS identifiers in the genome browser of each participant. We expect to be able to expand this over the next year to around 18 000 transcripts where we currently differ by only one or two amino acids by improvements in all three pipelines.

Figure 1.

The progressive improvement in the quality of human and mouse gene builds by comparison to curated protein and mRNA reference sequences is shown. The column legends indicate the species, reference dataset and assembly release number. UniSw indicates the Swiss-Prot (curated) part of UniProt. RefSeq indicates the curated part of RefSeq (i.e. excluding XP entries). Identical trends are seen in all four comparisons of human and mouse against UniSw and RefSeq. The four colours indicate the quality of the match to the reference dataset: blue indicates an exact match; maroon indicates matched ends with some internal mismatch/indel; yellow indicates an incomplete match and green indicates reference sequences that are missing from the gene build. There are multiple reasons for this improvement, including improvements in assembly quality, cDNA resources and algorithmic improvements to the gene build.

Over the next year we anticipate incorporating into Ensembl the genomes of a number of mammals that have been sequenced at low-coverage [2× whole genome shotgun (WGS)] and will therefore be highly fragmentary. The standard Ensembl gene build pipeline is unsuitable for such assemblies, so we have been developing a new method that utilizes a whole genome alignment to an annotated reference genome. In this method gene structures on the low-coverage assembly are derived largely by projecting gene structures from the reference genome. We have tested this approach on the initial cow genome assembly (Btau_1.0: 3× WGS), in this case using Homo sapiens as the reference genome. We were able to build good quality gene models from around 17 000 of the 22 000 available human genes. The projection was also used to organize cow assembly fragments into gene_scaffolds, although many of the gene annotations are still fragmented. A new higher quality cow genome assembly is now available (Btau_2.0: 6× WGS) which is more suitable for the standard Ensembl gene build pipeline. We, therefore, plan to compare the gene sets to further evaluate and refine this low-coverage build procedure.

Regulatory regions

The genome encodes far more than just the protein and RNA genes; in addition, the regulation of gene expression is a crucial area. The regulatory code for large eukaryotic genomes remains opaque to comprehensive analysis. However there have been a number of resources, developed recently, which start to make genome-wide prediction sets for regulatory regions. We have developed a database schema and visualization schemes for storing, manipulating and using these regulatory regions, allowing a user to move from a gene to its putative regulation to (where assigned) its putative regulator. The first datasets that we will put into this system are the CisRED resource (http://www.cisred.org) and the MiRanda miRNA target prediction (10), but we hope to expand this area rapidly as new techniques are developed.

Variation resources

A number of genomes, in particular human, have extensive resources on natural polymorphisms. These are predominantly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) but also include small scale insertions and deletions. For a number of variations, large-scale genotyping projects have provided reference datasets for human variation, e.g. the HapMap project (11). We have developed a new system for handling variations which can store both variations in ‘natural’ populations (such as Human) and variations between lab managed strains (such as Mouse). These variants are cross-correlated with functional information, such as coding regions, splice sites and regulatory regions to provide potential consequences of a variation.

The genotyping of large numbers of individuals provides important information on the correlation of variation between individuals. This correlation is due to both the ancestry of individuals and the variability in recombination rates described collectively as linkage disequilibrium. These correlations are invaluable in both the design and the interpretation of human variation information. We have precomputed the two common measures of pairwise linkage disequilibrium, r2 and d′, for all pairs of SNPs at a distance of under 100 kb that have been genotyped in the Perlegen (12) and HapMap (13) populations. In theory this would generate over one billion pairwise LD values, but in many cases these values are low (and so uninteresting). We store values where the r2 is >0.05, which generates around 135 million stored LD values. These correlations require some additional estimation of the missing phase information, which we have achieved with a simple expectation maximization of the double heterozygote. These precomputed tables are invaluable for researchers who do not have access to large computational resources, but of course do not replace more sophisticated methods for variation analysis, e.g. haplotype reconstruction using Haploview (14).

In addition we can efficiently store resequencing data, which is expected to become a larger source of polymorphism information in the future. For resequencing data we store both the individual variations (in the case of unphased data, as genotype calls) and the areas in which variation could have been observed. This latter ‘coverage’ information is crucial for understanding the potential variants between two individuals.

In the future we see increasing utility for these variation resources, in particular for the assessment of purifying selection on particular regions of the genome and in describing the potential functional variation between individuals or between laboratory strains.

Comparative genomics

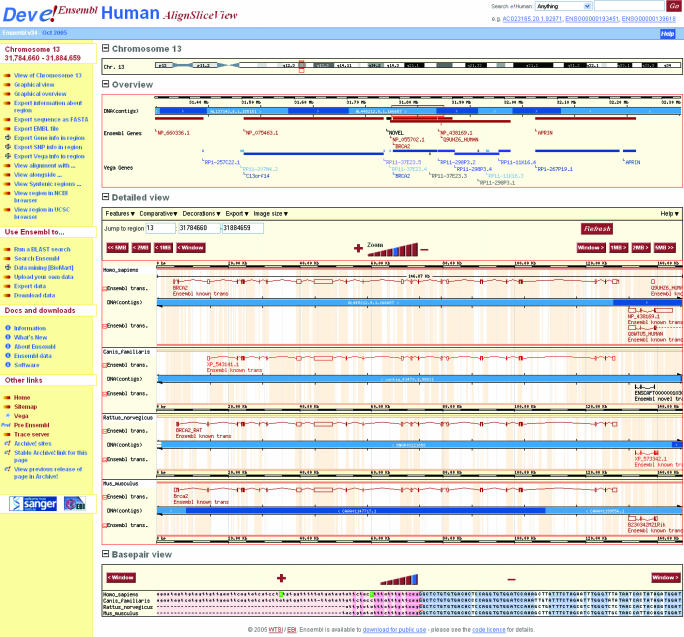

The ability to calculate and display integrated comparative genomics resources has been an important part of Ensembl. We have extended the comparative genomics systems in two ways. First, we have the ability to calculate, store and visualize multiple alignments of genome sequence. This is achieved by having a general schema for storing multiple alignments which does not require any particular reference sequence for the alignment. We will publish details of this storage method in a subsequent paper. This schema can be populated by a combination of a genome-wide orthology mapper, such as Mercator, and a region based multiple alignment tool, such as MAVID (10) or Mlagan (15). We can also visualize the resulting alignment with annotations mapped on to a common coordinate system, as shown in Figure 2. Importantly this common coordinate system need not be any of the aligned genomes, but could, for example, be the hypothesized ancestral sequence.

Figure 2.

A screenshot of the new alignslice view that is enabled by the multiple genome alignment. The top panel shows the human, rat and mouse genomes around the BRCA2 locus. The lower panel shows the base-pair alignment at the end of an exon (highlighted in the top panel by the central red box on human). In the base-pair view, exonic bases are blue and intronic bases are pink, with darker shades indicating conservation. Exon boundaries are highlighted with a red inverted L and SNPs are shown in red.

The gene level comparative genomics resources have also been updated to be based around protein tree calculations rather than best reciprocal similarity relationships. This provides better coverage (in particular for deeper relationships, e.g. vertebrate to Drosophila), better resolution of paralogy events and a more consistent way to examine evolutionary interesting events, e.g. positive selection detection via Ka/Ks studies.

Code portability and reuse

Ensembl not only provides a user-friendly website, but also provides a number of programmatic interfaces. The Ensembl system can be remotely installed on any UNIX based system and many of its components can be extended or reused. To maximize the utility of Ensembl we have both improved documentation resources and also labelled each API (application programming interface) function as ‘stable’, ‘moderate risk’ or ‘at risk’. Stable functions we guarantee will exist in our API with an unchanged functional signature for at least 2 years. At risk functions are those which we know are likely to change in the future as they are under development. Currently we have 512 (82%) stable functions in our API.

The Ensembl pipeline is also improving in its modularity and documentation. There is extensive documentation for running the pipeline in the openly accessible CVS repository. We have successfully installed the Ensembl pipeline at a separate institute, Baylor College of Medicine where it is currently being used for their own annotation needs. Our experience is that the most complicated aspects of running the Ensembl pipeline is the precise layout of the computer resources and then the correct configuration of the analysis routines to use for a particular organism.

The Ensembl website has not only had improvements in usability but also has a far more flexible plug-in system in the HTML generation. This allows remote sites which have extended or adapted Ensembl far more control over their local pages, with the ability to override nearly any aspect of the Ensembl website with local plug-in scripts.

We are open towards collaborations; all of Ensembl is openly licensed and can be easily downloaded without any registration. In addition we are happy to host other bioinformatics researchers on site for people to rapidly learn or adapt Ensembl. Interested researchers should contact helpdesk@ensembl.org. For more general wet-laboratory usage we regularly organize courses at different institutions that can be tailored to the specific biological areas of interest to attendees.

Data mining interfaces

We deployed a full featured BioMart (16,17) for Ensembl in Spring 2005. BioMart is a data mining federation technology which was spun out from the main Ensembl group as it is appropriate for more than just Ensembl. The BioMart system allows easy query federation across Internet accessible BioMarts. Currently these include Ensembl, WormBase, UniProt and MSD. We expect many other Marts to be developed over time.

Web usability and web service integration

We investigated new layouts of the Ensembl pages to provide better discoverability of information. With the help of specific focus groups spanning a variety of scientific backgrounds, we settled on the new design with a context dependent link bar to the left of the main pages. This bar suggests relevant ‘next links’ for investigation. We will continue to make reasonable changes in web interface aiming to make as much information about genomic regions and genes as intuitive as possible.

We have also continued to integrate with other resources using the distributed annotation system (DAS) protocol (18). We have reused the DAS protocol to work on both protein and ‘gene’ level, allowing remote sites to show features from their servers directly on Ensembl displays. The website uses the coordinate remapping features of the core Ensembl API to allow DAS sources provided on one coordinate system to be projected onto another. For example, this allows annotation on UniProt coordinates to be displayed on Ensembl protein pages, projected onto Ensembl peptide coordinates. The EU BioSapiens collaborative project (www.biosapiens.info), where a large number of different groups are providing genome and protein sequence annotation, has adopted DAS and more than 50 sources are already available. With the Ensembl website's coordinate projection facilities, all this annotation, much of which is on UniProt coordinates, can be displayed in Ensembl as well as other DAS clients (19).

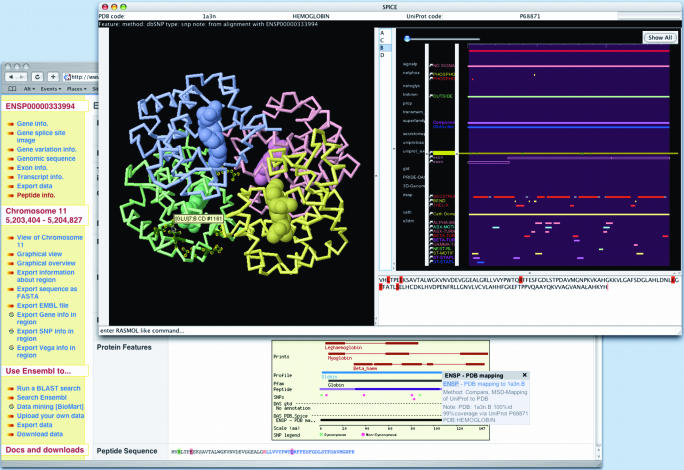

With the increasing number of DAS sources it had become hard to keep track of them and their different coordinate systems. To address this a DAS registry has been developed (http://das.sanger.ac.uk/registry/, A. Prlic et al., manuscript in preparation) as a central point where authors of DAS sources can register them. The Ensembl website is integrated with the registry making it is easier to attach DAS sources to Ensembl displays. DAS has also allowed Ensembl annotation data to be made available in other specialist DAS clients. For example, the SPICE DAS client (20) allows annotation on UniProt coordinates to be displayed on protein 3D structures (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The integration between Ensembl and the DAS protein 3D structure viewer SPICE is shown. The proteinview page of Ensembl shows the beta-globin gene HBB on chromosome 11. One of the non-synonymous SNPs is the sickle cell mutation at residue 7 (glutamic acid to valine). The PDB_spice DAS track shows a link to the PDB entry 1A3N chain B. In the SPICE window, which was opened by clicking on this track, the four chain structure of haemoglobin is shown on the left. The DAS annotations for the selected chain (B) are shown on the right. The uniprot_exon SNP DAS source is selected and the six SNPs are highlighted in the sequence of the chain (bottom right) and shown in the structure (dark green side chains with yellow highlights). Holding the mouse over residues in the structure panel shows the position of residue 7. Ensembl exposes its precalculated alignments between UniProt and Ensembl gene annotation as DAS sources (uniprot_exon).

CONCLUSIONS

Ensembl continues to grow in size, quality and functionality. Fundamentally our main goal of making large vertebrate genomes useful to the scientific community has not changed, but the number of species, depth of analysis and usability of our systems are constantly improving. We are looking forward to new resources such as Chip/Chip datasets and proteomic resources, many of which are in successful pilot phases (11,21). Overall we provide a robust and accurate database of information on chordate genomes, aimed at enabling other groups to maximally exploit these genomes.

Acknowledgments

The Ensembl project is principally funded by the Wellcome Trust with additional funding from EMBL, NIH-NIAID and BBSRC. We are grateful to users of our website and the developers on our mailing lists for much useful feedback and discussion. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments on this paper. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by The Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hubbard T., Andrews D., Caccamo M., Cameron G., Chen Y., Clamp M., Clarke L., Coates G., Cox T., Cunningham F., et al. Ensembl 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D447–D453. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curwen V., Eyras E., Andrews T.D., Clarke L., Mongin E., Searle S.M., Clamp M. The Ensembl automatic gene annotation system. Genome Res. 2004;14:942–950. doi: 10.1101/gr.1858004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R., Finn R.D., Hollich V., Griffiths-Jones S., Khanna A., Marshall M., Moxon S., Sonnhammer E.L., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrents D., Suyama M., Zdobnov E., Bork P. A genome-wide survey of human pseudogenes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2559–2567. doi: 10.1101/gr.1455503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z., Gerstein M. Large-scale analysis of pseudogenes in the human genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2004;14:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furey T.S., Diekhans M., Lu Y., Graves T.A., Oddy L., Randall-Maher J., Hillier L.W., Wilson R.K., Haussler D. Analysis of human mRNAs with the reference genome sequence reveals potential errors, polymorphisms, and RNA editing. Genome Res. 2004;14:2034–2040. doi: 10.1101/gr.2467904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birney E., Clamp M., Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slater G.S., Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashurst J.L., Collins J.E. Gene annotation: prediction and testing. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2003;4:69–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright A.J., John B., Gaul U., Tuschl T., Sander C., Marks D.S. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The ENCODE Project Consortium. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science. 2004;306:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinds D.A., Stuve L.L., Nilsen G.B., Halperin E., Eskin E., Ballinger D.G., Frazer K.A., Cox D.R. Whole-genome patterns of common DNA variation in three human populations. Science. 2005;307:1072–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1105436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrett J.C., Fry B., Maller J., Daly M.J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brudno M., Do C.B., Cooper G.M., Kim M.F., Davydov E., Green E.D., Sidow A., Batzoglou S. LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: efficient tools for large-scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 2003;13:721–731. doi: 10.1101/gr.926603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasprzyk A., Keefe D., Smedley D., London D., Spooner W., Melsopp C., Hammond M., Rocca-Serra P., Cox T., Birney E. EnsMart: a generic system for fast and flexible access to biological data. Genome Res. 2004;14:160–169. doi: 10.1101/gr.1645104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durinck S., Moreau Y., Kasprzyk A., Davis S., De Moor B., Brazma A., Huber W. BioMart and Bioconductor: a powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3439–3440. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowell R.D., Jokerst R.M., Day A., Eddy S.R., Stein L. The distributed annotation system. BMC Bioinformatics. 2001;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones P., Vinod N., Down T., Hackmann A., Kahari A., Kretschmann E., Quinn A., Wieser D., Hermjakob H., Apweiler R. Dasty and UniProt DAS: a perfect pair for protein feature visualization. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3198–3199. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prlic A., Down T., Hubbard T.J.P. Adding some SPICE to DAS. Bioinformatics. 2005;21 suppl 2:ii40–ii41. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desiere F., Deutsch E.W., Nesvizhskii A.I., Mallick P., King N.L., Eng J.K., Aderem A., Boyle R., Brunner E., Donohoe S., et al. Integration with the human genome of peptide sequences obtained by high-throughput mass spectrometry. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]