Abstract

LIFEdb (http://www.LIFEdb.de) integrates data from large-scale functional genomics assays and manual cDNA annotation with bioinformatics gene expression and protein analysis. New features of LIFEdb include (i) an updated user interface with enhanced query capabilities, (ii) a configurable output table and the option to download search results in XML, (iii) the integration of data from cell-based screening assays addressing the influence of protein-overexpression on cell proliferation and (iv) the display of the relative expression (‘Electronic Northern’) of the genes under investigation using curated gene expression ontology information. LIFEdb enables researchers to systematically select and characterize genes and proteins of interest, and presents data and information via its user-friendly web-based interface.

INTRODUCTION

LIFEdb (1) has been implemented towards the integration, mining and visualization of functional genomics data. The system was designed to cope with large amounts of heterogeneous data originating from high-throughput experimental approaches (2) and to relate these data with information from an automatic bioinformatics analysis of the proteins investigated (3).

The LIFEdb web-interface provides integrated access to cDNA-data, experimental results and bioinformatics information via several search forms, enabling researchers to systematically select and characterize genes and proteins of interest. By linking results to further external databases, the user is empowered to view the functional information within a larger context. Here we describe the newly added content in the LIFEdb database and highlight recent developments of interfaces to query and visualize the data.

NEW LAYOUT AND ADDED FUNCTIONALITY

The user interface has been completely updated and revised (Figure 1). Search fields are grouped into panels according to functionality. Users may either use the simple search field with a built-in analysis logic recognizing the type of input string or use additional fields to search for biological identifiers or experimental results. We have added a configurable search page in which groups of search fields can be selected or de-selected. The groups comprise experimental results, predictions, cDNA/protein data and keyword fields. The criteria of the respective groups can be connected by logical operators (‘AND’, ‘OR’). This allows for a ‘fine tuning’ of search capabilities.

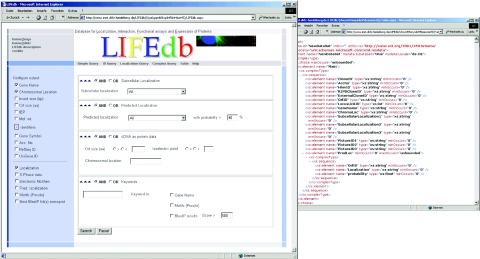

Figure 1.

The new LIFEdb web-interface. Users can choose between several search forms and are able to customize the output to display features of interest (left). All search results can be downloaded in XML (right).

Users can customize the output by selecting the experimental data or additional information to be displayed. The latter comprises annotations (gene names, chromosomal position of the cDNAs), identifiers (gene symbols, cDNA accession numbers, RefSeq/UniGene IDs) and bioinformatics analysis data (predictions, protein motifs). By default, results are shown in a tabular format but they can be downloaded as XML as well, to allow further processing with spreadsheets, databases or statistics software.

NEWLY ADDED DATA

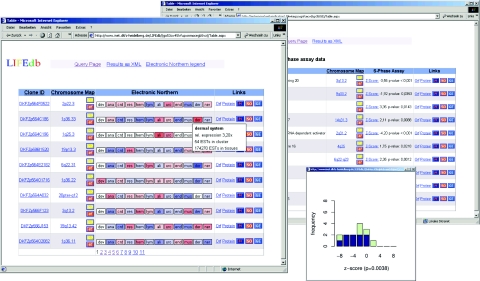

LIFEdb was initially developed to publish data on full-length cDNAs and the subcellular localization of the encoded proteins (4). During the past two years the content of the database has constantly grown to currently contain data on 1500 cDNAs and localizations and microscopic images of some 1000 proteins. We have now integrated a first dataset from a cell-based screening assay that addresses the influence of protein-overexpression on cell proliferation (5). This screen comprised initially 103 proteins and is the first posting of such high-throughput data in an open-access database (Figure 2). Expression constructs encoding proteins of interest and fused to green fluorescent protein derivates at either their N- or C-terminus were transfected into mammalian cells, and effects of protein-overexpression on G1/S-phase transition were measured. This was done using a high-content screening microscope by monitoring the incorporation of BrdU through immunofluorescent staining. The data were statistically analysed using a linear model correcting for systematic and random errors. This resulted in a Z-score, based on a smoothed local regression function for each single experiment. Proteins with positive values of Z are considered to be an activator and those having a negative value to be a repressor of cell proliferation. The results for each investigated protein were calculated as the median value of the Z-scores of all replicate experiments carried out with the respective ORF. To obtain a measure of the significance (P-value), the set of Z-scores of one protein was compared with the overall distribution of Z-scores for all proteins via the two-sided Wilcoxon test. Results from the cellular screen can be searched for with a suitable search field, where users can specify if activators, repressors or both are to be displayed and where they are able to define a cut-off for the minimal accepted P-value. Results are displayed as an extra column showing the median Z-score and the accompanying P-value. The distribution of the Z-scores for each ORF can be viewed as a histogram in an extra window (see Figure 2) that is accessible via a hyperlink. There, the data on N-terminal fusion constructs (CFP–ORF) are displayed in dark blue and values from C-terminal fusion constructs (ORF–YFP) are displayed in green. The numbers of proteins with attached information from functional profiling will continuously increase as more proteins are screened.

Figure 2.

Presentation of new data in LIFEdb. ‘Electronic Northern’ data are shown color-coded indicating the relative over-representation (red) or under-representation (blue) of the displayed genes in several tissues. Details are shown by moving the mouse over the respective tissue (left). Results of S-Phase assays are shown in a separate column with an extra window ploting the Z-scores of the single experiments for each protein (right) and the statistical significance of the result (P-value).

In addition to these experimental results, we included data on the relative tissue expression of the genes under investigation (‘Electronic Northern’, Figure 2). The calculation is based on the number of ESTs for every gene that were sequenced mostly in large scale projects (6–10). We used the UniGene (11) EST-dataset and eVOC ontologies (12) which curate this dataset in a detailed manner, to obtain a controlled tissue vocabulary. dbEST library mappings to the ontologies were obtained from the eVOC website (http://www.evocontology.org). The first level terms of the ontology ‘Anatomical System’ were used for the tissue-definitions (for a list, see http://www.inet.dkfz-heidelberg.de/LIFEdb/ENorthernLegend.htm). All EST-libraries assigned to the respective term (or sub-term) were pooled. cDNAs were mapped to UniGene cluster IDs via the GenBank accession number in the UniGene dataset.

The relative gene expression of one transcript was calculated using the number of ESTs in the respective UniGene cluster belonging to each ontology term which was then normalized for each term (for details on the calculation see http://www.dkfz.de/mga/groups.asp?siteID=160).

The datasets, mappings and calculations are updated when new versions of the respective datasets become available.

The expression for each gene is shown for the terms of the anatomical system as colored boxes in the table output. Boxes are labeled with an abbreviation of the underlying definition. Relative gene expression values are indicated by different colors. Values <1 (relative ‘under-expression’) are displayed in blue and values >1 are in red (relative ‘overexpression’). Darker colors represent a higher degree of under- or overexpression. Boxes in white indicate that no UniGene expression of the respective gene was identified in that particular group of tissues. Information on the underlying numbers (ESTs in the respective cluster and tissues) is displayed upon moving the mouse over the boxes. This information is included in the XML output.

FUTURE EXTENSIONS

In the future, we will integrate results from further ongoing cellular screens and extend the cDNA-annotation by integrating other external databases that cover for instance IPI identifiers and ontology terms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Genome Research Network grants 01GR0101 and 01GR0420 by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), and in part by EU grant 503438 (TRANSFOG). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannasch D., Mehrle A., Glatting K.H., Pepperkok R., Poustka A., Wiemann S. LIFEdb: a database for functional genomics experiments integrating information from external sources, and serving as a sample tracking system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D505–D508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiemann S., Arlt D., Huber W., Wellenreuther R., Schleeger S., Mehrle A., Bechtel S., Sauermann M., Korf U., Pepperkok R., et al. From ORFeome to biology: a functional genomics pipeline. Genome Res. 2004;14:2136–2144. doi: 10.1101/gr.2576704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.del Val C., Mehrle A., Falkenhahn M., Seiler M., Glatting K.H., Poustka A., Suhai S., Wiemann S. High-throughput protein analysis integrating bioinformatics and experimental assays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:742–748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson J.C., Wellenreuther R., Poustka A., Pepperkok R., Wiemann S. Systematic subcellular localization of novel proteins identified by large-scale cDNA sequencing. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:287–292. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arlt D., Huber W., Schmidt C., Liebel U., Rosenfelder H., Bechtel S., Mehrle A., Bannasch D., Schupp I., Seiler M., et al. Functional profiling: from microarrays via cell-based assays to novel tumor relevant modulators of the cell cycle. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7733–7742. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams M.D., Kelley J.M., Gocayne J.D., Dubnick M., Polymeropoulos M.H., Xiao H., Merril C.R., Wu A., Olde B., Moreno R.F., et al. Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project. Science. 1991;252:1651–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.2047873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strausberg R.L., Buetow K.H., Emmert-Buck M.R., Klausner R.D. The cancer genome anatomy project: building an annotated gene index. Trends Genet. 2000;16:103–106. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiemann S., Weil B., Wellenreuther R., Gassenhuber J., Glassl S., Ansorge W., Bocher M., Blocker H., Bauersachs S., Blum H., et al. Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs. Genome Res. 2001;11:422–435. doi: 10.1101/gr.154701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strausberg R.L., Feingold E.A., Grouse L.H., Derge J.G., Klausner R.D., Collins F.S., Wagner L., Shenmen C.M., Schuler G.D., Altschul S.F., et al. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16899–16903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242603899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ota T., Suzuki Y., Nishikawa T., Otsuki T., Sugiyama T., Irie R., Wakamatsu A., Hayashi K., Sato H., Nagai K., et al. Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs. Nature Genet. 2004;36:40–45. doi: 10.1038/ng1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler D.L., Barrett T., Benson D.A., Bryant S.H., Canese K., Church D.M., DiCuccio M., Edgar R., Federhen S., Helmberg W., et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D39–D45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelso J., Visagie J., Theiler G., Christoffels A., Bardien S., Smedley D., Otgaar D., Greyling G., Jongeneel C.V., McCarthy M.I., et al. eVOC: a controlled vocabulary for unifying gene expression data. Genome Res. 2003;13:1222–1230. doi: 10.1101/gr.985203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]