Abstract

A challenge in strain construction is that unmarked deletion and nucleotide substitution alleles generally do not confer selectable phenotypes. We describe here a rapid and efficient strategy for transferring such alleles via generalized transduction. The desired allele is first constructed and introduced into the chromosome by conventional allelic-exchange methods. The suicide vector containing the same allele is then integrated into the mutant chromosome, generating a tandem duplication homozygous for that allele. The resulting strain is used as a donor for transductional crosses, and selection is made for a marker carried by the integrated suicide vector. Segregation of the tandem duplication results in haploid individuals, each of which carries the desired allele. To demonstrate this mutagenesis strategy, we used bacteriophage P22Hint for generalized transduction-mediated introduction of unmarked mutations to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. This method is applicable to any species for which generalized transduction is established.

Bacterial allelic exchange mediated by recombinant suicide vectors has been used extensively to introduce recombinant or mutated alleles into the chromosomes of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (19, 36). Suicide plasmid vectors have common characteristics, such as a narrow host range for replication restricted to a few bacterial strains (19, 22), growth at a higher temperature in the case of temperature-sensitive replicons (14), genes inducing antibiotic resistance, and multiple cloning sites. In addition, to facilitate selection for mutated alleles, many suicide vectors contain genes for counterselection, such as rpsL by streptomycin sensitivity (35, 38), tetAR by fusaric acid selection (20), and sacB by sucrose sensitivity (12, 29). Recombinant suicide plasmids can be delivered to recipient strains by transduction, electroporation, or conjugation.

Generalized transduction is a genetic process widely used for the transfer of bacterial DNA from a donor strain to recipient cells via transducing bacteriophages such as P1 for Escherichia coli (18, 37) and P22 for Salmonella spp. (37, 40). The large headful packaging capacity, ca. 100 kb for P1 and 44 kb for P22, facilitates transfer of genomic regions containing selectable insertions such as transposons, antibiotic resistance cassettes, and gene operon fusions. The high-frequency transducing bacteriophage P22HTint (33) is commonly used for transduction of chromosomal or plasmid DNA in Salmonella spp. (6, 19, 25). Since the overall probability of generalized transduction is low, selectable markers are required to identify and recover transductants. Therefore, generalized transduction is not practical for the transfer of bacterial alleles containing unmarked or unselectable mutations to recipient bacteria. We have developed a new efficient strategy to transfer unmarked, unselectable defined deletion (Δ) and point mutations. The strategy combines the use of suicide vector-mediated gene replacement and bacteriophage-mediated generalized transduction. This method is effectively used here to introduce unmarked mutations into Salmonella enterica servovar Typhimurium recipient strains by phage P22HTint-mediated generalized transduction. This mutagenesis strategy can also be adapted to any species for which generalized transduction is established.

Table 1 lists the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study. Bacteriophage P22HTint (33) was used for generalized transduction. E. coli and serovar Typhimurium were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (2). When required, antibiotics were added to the culture medium at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 12 μl/ml; and tetracycline, 15 μg/ml. Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was added (50 μg/ml) for the growth of Asd− strains (24). LB agar containing 5% sucrose was used for sacB-based counterselection in the allelic-exchange experiments (12). General DNA isolation and enzymatic manipulations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (32). Transfer of recombinant suicide plasmids to Salmonella was accomplished by conjugation by using E. coli MGN-617 (Asd−) (30) as the plasmid donor. Salmonella transconjugants were selected on LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics. The crude colicin B extract was prepared from E. coli DM1187 harboring plasmid p3Z/ColB by the procedure described by Brickman and Armstrong (4).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Derivation, source, or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DM1187 | lexA51 lexA3 | 23 |

| MGN-617 | thi-1 thr-1 leuB6 fhuA21 lacY1 glnV44 ΔasdA4 recA1 RP4 2-Tc::Mu [λpir], Kmr | 30 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ||

| χ3339 | SL1344 hisG | 13 |

| χ3761 | UK-1 wild-type | 8 |

| χ4666 | SR-11, agfD812 (AgfC) | Lab collection |

| χ8505 | hisG agfD812 (AgfC) | χ3339 |

| χ8554 | hisG ΔasdA16 | χ3339 |

| χ8680 | hisG ΔasdA16::pMEG-443, Apr Cmr | χ8554 |

| χ8706 | agfD812 (AgfC) | χ3761 |

| χ8739 | hisG agfD812::pYA3490, Tetr | χ8505 |

| Plasmids | ||

| p3Z/ColB | Colicin B expression plasmid, Apr | 4 |

| pYA3342 | Asd+ vector, pBR ori | Lab collection |

| pYA3490 | pDMS179 (9) derivative recombinant suicide plasmid containing 0.8 kb agfD812 constitutive promoter region of χ4666, Tcr | Lab collection |

| pMEG-443 | pMEG-375 derivative recombinant suicide plasmid to generate SalmonellaΔasdA16 mutant, Apr Cmr | Megan Health, Inc. |

Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Km, kanamycin; Tc, tetracycline. AgfC, constitutive expression of aggregative fimbriae.

Bacteriophage P22HTint was propagated on Salmonella donor strains by standard methods (19, 27, 37). Plaque assays were performed to determine phage titers. To eliminate multiple phage infections, P22HTint was used to infect recipient serovar Typhimurium strains with a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 (phage/recipient). Transductants were selected on LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics and EGTA at 10 mM (27). Green indicator plates (27) and P22 H5 (19) were used to confirm that transductants were phage-free and not P22 lysogens.

Generation of a ΔasdA16 deletion mutation in serovar Typhimurium by conventional allelic exchange.

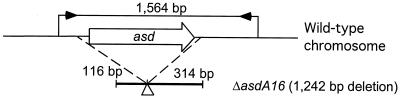

Initial test of the mutation strategy involved the transfer of the unmarked Δasd mutation to serovar Typhimurium strains. The asd gene is essential and codes for β-aspartic semialdehyde dehydrogenase; asd mutants require DAP for their growth (11, 24). The mutagenic recombinant suicide plasmid pMEG-443 (9.7 kb) has 1,242 bp of the asd region (ΔasdA16) deleted (Fig. 1). To construct a serovar Typhimurium ΔasdA16 mutant, plasmid pMEG-443 was conjugationally transferred from E. coli χ7213 to wild-type strain serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (χ3339). Strains containing single-crossover plasmid insertions (χ3339 asd::pMEG-443) were isolated on plates containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. Loss of the suicide vector after the second recombination between homologous regions (i.e., allelic exchange) was selected for by using the sacB-based sucrose sensitivity counterselection system (12). For selection of the Δasd Salmonella recipient, DAP was added to the medium, and colicin B extract was used for growth limitation of the E. coli MGN-617 (Asd−) donor strain (4). From the χ3339 asd::pMEG-443 transconjugant, serovar Typhimurium ΔasdA16 allelic-exchange mutants requiring DAP for growth were isolated with extremely low frequency. One ΔasdA16 mutant, designated χ8554 (Table 1), was identified from five independent sets of experiments. Relatively short asd-flanking sequences, 116 and 314 bp, in pMEG-443 (Fig. 1) may be of insufficient length for efficient recombination, resulting in extremely low frequencies of the desired second crossover events. The presence of the ΔasdA16 allele in χ8554 was confirmed by PCR amplification of smaller DNA fragments and comparison with those amplified from wild-type χ3339. An asd primer set (5′-CGGAAATGATTCCCTTCCTAACG-3 and 5′-TATCTGCGTCGTCCTACCTTCAG-3′) amplified 1,564- and 322-bp DNA fragments from the chromosomal template DNA of χ3339 (Asd+) and the χ8554 (ΔasdA16) mutant, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of a recombinant construct containing a defined deletion. The map presents the recombinant ΔasdA16 (1,242-bp) region deleted from the suicide plasmid pMEG-443. Open arrow indicates the coding region of the asd gene, and dotted lines represent the limits of the deleted region. The deletion is shown as an open triangle, and the sizes of the flanking DNAs adjacent to the deletion on the suicide vector are indicated. The position and orientation of PCR primers used in this study are indicated by solid arrows on the map of wild-type DNA. The sizes of the PCR amplified products from the wild-type and ΔasdA16 DNAs are 1,564 and 322 bp, respectively.

In the general application of the initial suicide plasmid-based strategy, construction of a pair of recombinant suicide plasmids may be a practical and convenient means to perform the overall processes described above. This may be particularly true when allelic exchange to generate a strain with a mutation having no selectable phenotype is rare, such as the ΔasdA16 mutation. In this instance, one plasmid is designed to contain a selectable marker between two flanking regions involved in the homologous recombination, whereas another plasmid carries the same recombinant construct without the intervening selectable marker. Identification of strains with mutations introduced by allelic exchange is most easily achieved by using selectable markers that are inserted within the recombinant construct to remain in the chromosome after recombinational loss of the suicide vector. The introduced selectable marker in the allele can then be removed by another allelic exchange with the suicide plasmid containing the recombinant defined deletion construct in which the selectable marker is absent. The resulting strain bearing the defined markerless deletion can then serve as the unmarked allelic donor for the transduction-mediated allele transfer approach described below.

Efficient transfer of a ΔasdA16 deletion mutation by using generalized transduction.

The two allelic-exchange methods described above illustrate that isolation of a strain with a desired unmarked mutation such as the ΔasdA16 mutation can be quite difficult. Introduction of such mutations in different strain backgrounds would necessitate repetition of this entire procedure each time for each strain. However, by using a generalized transduction strategy the problems associated with transfer of unmarked deletions based solely on the allelic-exchange procedure can be alleviated. Once deletion mutants are constructed and identified through conventional allelic-exchange procedures, the same deletion mutation can then be transduced efficiently to other strains without the need of extensive screening procedures. Our simple strategy is described below.

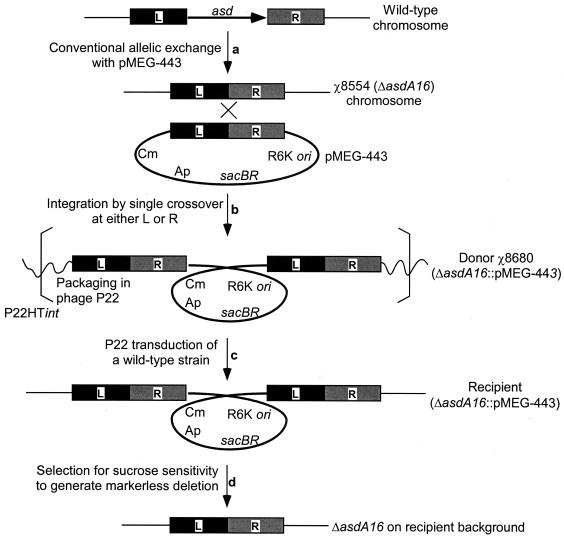

Suicide plasmid pMEG-443 was integrated into the chromosome of serovar Typhimurium deletion mutant χ8554 (ΔasdA16) as described above. Integration of the suicide plasmid generates a tandem duplication homozygous for the Δasd region, and a single clone designated χ8680 (ΔasdA16::pMEG-443) was selected for further experiments. Since the parent strain χ8554 already contains the Δasd mutation generated by using pMEG-443, integration of this plasmid does not change the nucleotide sequences of the deletion region but results in duplication of the deletion regions of the strain. This duplication of the deletion region is the particular advantage of our new mutagenesis strategy. The integrated suicide vector provides a closely linked tag within the genetic region of interest that now contains a selectable marker for transduction and, in theory, all transduced clones selected for a second-crossover recombination and loss of the suicide vector should carry the defined deletion.

We hypothesized that the DNA packaging capacity of bacteriophage P22HTint (ca. 44 kb) (19) would permit efficient transduction of the deletion region containing the integrated suicide plasmid (9.7 kb) to other serovar Typhimurium recipients. Figure 2 illustrates this sequence of events for transfer of the ΔasdA16 mutation to a wild-type strain. The P22HTint lysate was prepared from propagation on serovar Typhimurium strain χ8680. To maintain the integrated suicide vector in cells during phage propagation, Salmonella donors were grown in medium containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. P22HTint lysates from strain χ8680 were used to transduce the recipient wild-type strain χ3339. Salmonella transductants for ΔasdA16::pMEG-443 were selected for chlorampenicol and ampicillin resistance encoded on the suicide vector. When the DNA region containing the integrated suicide vector was transduced to a recipient strain, all transductants exhibited the mutant phenotypes as predicted. Loss of the suicide plasmid was selected for by the sacB-based counterselection system used in the routine allelic-exchange procedure. All of the sucrose-resistant and antibiotic-sensitive clones from each of the transductants demonstrated the Asd− phenotype, demonstrating the high-efficiency transfer of the mutation. PCR amplification demonstrated identical fragment sizes for Δasd mutants generated by P22 transduction to those observed for strain χ8554 containing the original ΔasdA16 mutation (data not shown). The DAP requirement of serovar Typhimurium ΔasdA16 generated by the transduction protocol was complemented by introducing pYA3342 (Table 1), which contains a functional copy of the asd gene. These results demonstrated that the ΔasdA16 chromosomal deletion mutation was efficiently transduced to another strain by integration of a suicide plasmid carrying an antibiotic resistance gene and the sacB-mediated counterselection system, permitting selective loss of the integrated suicide vector after transduction.

FIG. 2.

Illustration of overall processes for transfer of the ΔasdA16 mutation. Black boxes and gray boxes represent cloned 5′ (left [L]) and 3′ (right [R]) flanking regions, respectively, of the asd gene. (Step a) Using the recombinant suicide plasmid pMEG-443, a ΔasdA16 mutant was generated by the routine allelic-exchange method. (Step b) Plasmid pMEG-443 was integrated into the chromosome of the χ8554 (ΔasdA16) strain by single-crossover insertion. (Step c) Phage P22HTint was propagated on the donor strain χ8680 (ΔasdA16::pMEG-443). The ΔasdA16::pMEG-443 complex was transduced to a wild-type recipient strain, and transductants were selected based on the plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance markers. (Step d) Excision of the plasmid by homologous recombination between duplicated regions was selected for by using the plasmid-carried sacB counterselection system to generate the unmarked deletion mutation.

Transduction of a single point mutation.

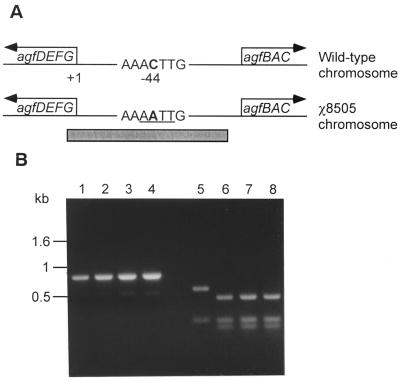

By using the same strategy, we hypothesized that when a suicide vector containing a gene sequence with a point mutation is integrated into the chromosomal gene with the point mutation, the antibiotic resistance gene encoded by the recombinant suicide vector would serve as a marker for transduction-mediated transfer of the point mutation to a different strain. To illustrate this procedure, we chose a point mutation within the promoter region of the agfD (csgD) gene, designated agfD812, of serovar Typhimurium χ4666 (31), resulting in constitutive expression of aggregative fimbriae (AgfC), also known as curli. In contrast to the smooth morphotype of wild-type salmonellae grown at 37°C, Salmonella strains that carry this point mutation produce wrinkled colonies on LB agar (5, 31). Strain χ4666 carries a prophage which provides immunity to phage P22, and phage P22HTint cannot be propagated on χ4666 (R. Curtiss III, unpublished data). To obtain a suitable donor for transduction of the point mutation, we introduced the agfD812 mutation into serovar Typhimurium χ3339 by conventional suicide vector-mediated allelic exchange by using the recombinant suicide plasmid pYA3490, which contains the 0.8-kb DNA fragment encompassing the agfD812 promoter region of χ4666 (Table 1). The presence of the agfD812 mutation was confirmed in a clone designated χ8505 (Fig. 3A). Serovar Typhimurium χ8505 was used as the allelic donor for transduction-mediated transfer of the agfD812 mutation.

FIG. 3.

Confirmation of point mutation transductants. (A) Intergenic region of divergent operons agfDEFG and agfBAC. The transcriptional orientation of each operon is indicated with arrows. The transcription start site of agfD is depicted as +1, and the cytosine residue from the wild type and the adenine residue from χ8505 at the −44 position (31) are indicated in boldface. The Tsp509I restriction enzyme site (AATT) created by a transversion is underlined. The gray bar represents the 0.8-kb agfD812 DNA region of suicide plasmid pYA3490. (B) DNA fragments were PCR amplified from the whole-cell lysate templates of the wild-type strain and three randomly picked transductants. Before (lanes 1 to 4) and after (lanes 5 to 8) DNA digestion with Tsp509I enzyme, DNA fragments were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel. Size markers are indicated. Lanes: 1 and 5, wild-type strain; 2 to 4 and 6 to 8, mutants carrying the point mutation.

After conjugational transfer of suicide plasmid pYA3490 (6.3 kb) to serovar Typhimurium χ8505 (AgfC), single-crossover transconjugants carrying the integrated suicide vector, χ8505 agfD::pYA3490, were selected in the presence of tetracycline. As with the transduction-mediated transfer of deletion mutations, integration of pYA3490 results in duplicate agfD812 promoters, both of which contain the point mutation. One of the single-crossover derivatives of χ8505 was designated χ8739 (Table 1). A phage P22HTint lysate was prepared by propagation on χ8739 donor cells grown in the presence of tetracycline, and the agfD812::pYA3490 complex was transduced to wild-type serovar Typhimurium UK-1 (χ3761). All transductants of χ3761 selected for tetracycline resistance encoded by the suicide vector exhibited wrinkled colonies on LB agar after growth at 37°C. From two single-crossover χ3761 agfD812::pYA3490 transductants, loss of the integrated suicide vector pYA3490 was selected for based on sacB counterselection. As expected, all tetracycline-sensitive colonies arising from excision of the suicide plasmid produced Agf and wrinkled colonies at 37°C. Since a transversion (C to A) at position −44 of the agfD812 transcription start site creates a Tsp509I restriction enzyme cleavage site (5′-AATT-3′), introduction of the point mutation was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing and Tsp509I enzyme digestion of the PCR-amplified agfD812 promoter regions from three suicide plasmid-excised recombinants (Fig. 3B). PCR primers were 5′-TGCTCTAGAATTATCCTGCCAATAGTGGAT-3′ and 5′-TGCGAGCTCAGAAGATAGTGTATCGCGCAC-3′. A representative strain was designated χ8706. By using an allele with a single-base-pair transversion in the agfD812 promoter region as an experimental example, we demonstrated the efficient transfer of a point mutation to a recipient strain by means of bacteriophage-mediated generalized transduction.

The strategy used to generate markerless mutations described here presents a distinct advantage for allele transfer. Once a defined markerless deletion, insertion, or point mutation has been created by conventional allelic exchange or other recent methods, including double-strand break gene replacement (26) and phage λ Red-mediated recombination (10), this unmarked allele can be transferred to other strains with high frequency. The major advantage of this strategy involves the integration of a recombinant suicide vector within the allele carrying the defined modification specified by the recombinant suicide vector. The antibiotic resistance marker encoded by the suicide vector permits efficient transfer of the mutant allele by generalized transduction to a recipient strain. Selection for the markerless defined mutation is then mediated by excision of the suicide vector based on the counterselection system it encodes. After transduction and homologous recombination for loss of the suicide vector between the duplicated regions, the desired defined mutation remains in the chromosome at a frequency of virtually 100%. Another convenient aspect of using phage to mediate allele replacement is that once a phage lysate is prepared from a donor strain containing a mutant allele and the integrated suicide vector specifying the same mutant allele, the same lysate can be used in consecutive experiments to transfer this mutation to other strains. The strategy used here could also be adapted to efficiently introduce markerless mutations in other bacterial species which have generalized transducing bacteriophages. In addition to phage P22 for serovar Typhimurium, potential phages that could be used for adaptation of this procedure in other species include phage P1 for E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae (37), phage F116 for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17), phage phi Cr30T for Caulobacter crescentus (1), phage N3 for Rhizobium meliloti (21), phage CTP1 for Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (39), phage Ba1 for Bordetella avium (34), phage CP-T1 for Vibrio cholerae (3), phage P35 or U153 for Listeria monocytogenes (15), phage 3 M for Serratia marcescens (28), and phage VSH-1 for Serpulina hyodysenteriae (16).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra K. Armstrong for providing plasmid p3Z/ColB. Sandra K. Armstrong and two anonymous reviewers offered valuable suggestions to improve the manuscript, which were helpful and appreciated.

This study was supported by NIH grants AI-24533 and DE-06669 and by NIH STTR grant R42 AI-38599.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender, R. A. 1981. Improved generalized transducing bacteriophage for Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 148:734–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani, G. 1952. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62:293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd, E. F., and M. K. Waldor. 1999. Alternative mechanism of cholera toxin acquisition by Vibrio cholerae: generalized transduction of CTXPhi by bacteriophage CP-T1. Infect. Immun. 67:5898–5905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brickman, T. J., and S. K. Armstrong. 1996. Colicins B and Ia as novel counterselective agents in interspecies conjugal DNA transfers from colicin-sensitive Escherichia coli donors to other gram-negative recipient species. Gene 178:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, P. K., C. M. Dozois, C. A. Nickerson, A. Zuppardo, J. Terlonge, and R. Curtiss III. 2001. MlrA, a novel regulator of curli (Agf) synthesis and extracellular matrix synthesis by Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 41:349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casjens, S., W. M. Huang, M. Hayden, and R. Parr. 1987. Initiation of bacteriophage P22 DNA packaging series. Analysis of a mutant that alters the DNA target specificity of the packaging apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 194:411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collinson, S. K., L. Emody, K. Muller, T. J. Trust, and W. W. Key. 1991. Purification and characterization of thin, aggregative fimbriae from Salmonella enteritidis. J. Bacteriol. 173:4773–4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtiss, R., III, S. B. Porter, M. Munson, S. A. Tinge, J. O. Hassan, C. Gentry-Weeks, and S. M. Kelly. 1991. Nonrecombinant and recombinant avirulent Salmonella live vaccines for poultry, p. 169–198. In L. C. Blankenship, J. S. Bailey, N. A. Cox, N. J. Stern, and R. J. Meinersmann (ed.), Colonization control of human bacterial enteropathogens in poultry. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 9.Edwards, R. A., L. H. Keller, and D. M. Schifferli. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbriae gene expression. Gene 207:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis, H. M., D. Yu, T. DiTizio, and D. L. Court. 2001. High-efficiency mutagenesis, repair, and engineering of chromosomal DNA using single-stranded oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6742–6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gálan, J. E., K. Nakayama, and R. Curtiss III. 1990. Cloning and characterization of the asd gene of Salmonella typhimurium: use in stable maintenance of recombinant plasmids in Salmonella vaccine strains. Gene 94:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gay, P., D. Le Coq, M. Steinmetz, T. Berkelman, and C. I. Kado. 1985. Positive selection procedure for entrapment of insertion sequence elements in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 164:918–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulig, P. A., and R. Curtiss III. 1987. Plasmid-associated virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 55:2891–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton, C. M., M. Aldea, B. K. Washburn, P. Babitzke, and S. R. Kushner. 1989. New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:4617–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodgson, D. A. 2000. Generalized transduction of serotype 1/2 and serotype 4b strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphrey, S. B., T. B. Stanton, N. S. Jensen, and R. L. Zuerner. 1997. Purification and characterization of VSH-1, a generalized transducing bacteriophage of Serpulina hyodysenteriae. J. Bacteriol. 179:323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidambi, S. P., S. Ripp, and R. V. Miller. 1994. Evidence for phage-mediated gene transfer among Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains on the phylloplane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:496–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lennox, E. S. 1955. Transduction of linked genetic characters of the host by bacteriophage P1. Virology 1:190–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maloy, S. R., V. J. Stewart, and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Genetic analysis of pathogenic bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 20.Maloy, S. R., and W. D. Nunn. 1981. Selection for loss of tetracycline resistance by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 145:1110–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin, M. O., and S. R. Long. 1984. Generalized transduction in Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 159:125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mount, D. W. 1977. A mutant of Escherichia coli showing constitutive expression of the lysogenic induction and error-prone DNA repair pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:300–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakayama, K., S. M. Kelly, and R. Curtiss III. 1988. Construction of an Asd+ expression-cloning vector: stable maintenance and high level expression of cloned genes in a Salmonella vaccine strain. Bio/Technology 6:693–697. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orbach, M. J., and E. N. Jackson. 1982. Transfer of chimeric plasmids among Salmonella typhimurium strains by P22 transduction. J. Bacteriol. 149:985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posfai, G., V. Kolisnychenko, Z. Bereczki, and F. R. Blattner. 1999. Markerless gene replacement in Escherichia coli stimulated by a double-strand break in the chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:4409–4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Provence, D. L., and R. Curtiss III. 1994. Gene transfer in gram-negative bacteria, p.317–347. In P. Gerhardt, R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg (ed.), Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Regue, M., C. Fabregat, and M. Vinas. 1991. A generalized transducing bacteriophage for Serratia marcescens. Res. Microbiol. 142:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ried, J. L., and A. Collmer. 1987. An nptI-sacB-sacR cartridge for constructing directed, unmarked mutations in gram-negative bacteria by marker exchange-eviction mutagenesis. Gene 57:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roland, K., R. Curtiss III, and D. Sizemore. 1999. Construction and evaluation of a Δcya Δcrp Salmonella typhimurium strain expressing avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 LPS as a vaccine to prevent airsacculitis in chickens. Avian Dis. 43:429–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Römling, U., W. D. Sierralta, K. Eriksson, and S. Normark. 1998. Multicellular and aggregative behaviour of Salmonella typhimurium strains is controlled by mutations in the agfD promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 28:249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Schmieger, H., and H. Backhaus. 1976. Altered cotransduction frequencies exhibited by HT-mutants of Salmonella-phage P22. Mol. Gen. Genet. 143:307–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shelton, C. B., D. R. Crosslin, J. L. Casey, S. Ng, L. M. Temple, and P. E. Orndorff. 2000. Discovery, purification, and characterization of a temperate transducing bacteriophage for Bordetella avium. J. Bacteriol. 182:6130–6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skorupski, K., and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene 169:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder, L., and W. Champness. 1997. Molecular genetics of bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 37.Sternberg, N. L., and R. Maurer. 1991. Bacteriophage-mediated generalized transduction in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Methods Enzymol. 204:18–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stibitz, S., W. Black, and S. Falkow. 1986. The construction of a cloning vector designed for gene replacement in Bordetella pertussis. Gene 50:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss, B. D., M. A. Capage, M. Kessel, and S. A. Benson. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a generalized transducing phage for Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. J. Bacteriol. 176:3354–3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zinder, N. D., and J. Lederberg. 1952. Genetic exchange in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 64:679–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]