Abstract

Ruminococcin A (RumA) is a trypsin-dependent lantibiotic produced by Ruminococcus gnavus E1, a gram-positive strict anaerobic strain isolated from a human intestinal microbiota. A 12.8-kb region from R. gnavus E1 chromosome, containing the biosynthetic gene cluster of RumA, has been cloned and sequenced. It consisted of 13 open reading frames, organized in three operons with predicted functions in lantibiotic biosynthesis, signal transduction regulation, and immunity. One unusual feature of the locus is the presence of three almost identical structural genes, all of them encoding the RumA precursor. In order to determine the role of trypsin in RumA production, the transcription of the rum genes has been investigated under inducing and noninducing conditions. Trypsin activity is needed for the growth phase-dependent transcriptional activation of RumA operons. Our results suggest that bacteriocin production by R. gnavus E1 is controlled through a complex signaling mechanism involving the proteolytic processing of a putative extracellular inducer-peptide by trypsin, a specific environmental cue of the digestive ecosystem.

Bacteria inhabit diverse ecological niches in which survival and adaptation depend on their capacity to sense the local environmental conditions and to regulate the expression of specific genes in response to external stimuli (13). A mechanism commonly found in prokaryotes for signal transduction involves the so-called two-component systems. They consist of a histidine protein kinase serving as a sensor of the cell’s environment and a cytoplasmic response regulator that modulates the internal adaptive response, in most cases by gene regulation. Communication between both proteins is carried out by the transfer of a phosphate group from the sensor to the effector (47, 48). In general, the specific binding of a signal molecule to the external domain of the histidine protein kinase triggers autophosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain at a conserved His residue. The phosphate group is then transferred to an Asp residue in the N-terminal domain of the response regulator, which can in turn mediate changes in target gene expression through its C-terminal DNA-binding effector domain. Many important bacterial growth phase-dependent processes, such as genetic transfer, chemotaxis, pathogenesis and antibiotic production, are controlled by this kind of system. In gram-positive bacteria, most of the extracellular signal molecules for cell-cell communication are self-produced peptides derived from a larger precursor by processing of the N-terminal leader region (13, 25).

Such peptide-dependent regulatory systems have recently been shown to participate in bacteriocin production. One of the best-characterized examples is the production of nisin by Lactococcus lactis. In addition to its antimicrobial activity, nisin functions as the inducer of its own synthesis through the nisKR two-component signal transduction system (27). In contrast, bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11 and Lactobacillus sake LTH673 is induced by bacteriocin-like peptides which are cotranscribed together with the genes encoding the two-component systems plnBCD and sspKR, respectively (7, 11).

Ruminococcus gnavus E1 is a gram-positive strict anaerobic strain isolated from a human intestinal microbiota. The E1 strain was initially identified as Peptostreptococcus sp. (36), but further characterization by DNA-DNA hybridization and 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) analysis indicated that it belongs to the Ruminococcus gnavus species (8). In the digestive tract of gnotobiotic rats, the E1 strain produces a trypsin-dependent antimicrobial substance involved in colonization resistance against Clostridium perfringens (36). A bacteriocin, named ruminococcin A (RumA), has been purified from in vitro cultures of the E1 strain and subsequently characterized (8). RumA belongs to the lantibiotic family of bacteriocins, which are posttranslationally modified peptides characterized by the presence of lanthionines, β-methyllanthionines, and dehydrated amino acid residues (41). Maturation of the modified precursors is finished by cleavage of the leader peptide and translocation across the cell membrane. The genetic determinants required for lantibiotic biosynthesis, modification, transport, producer self-immunity and, in some cases, also for regulation, are encoded by gene clusters which show similar organization (43). The in vitro production of RumA was been shown to be dependent on the presence of trypsin, one of the most abundant digestive proteases, in the culture medium. Previous results suggested that trypsin was involved in the induction of the bacteriocin synthesis rather than in the hypothetical activation of the secreted peptide by proteolysis (36). The action of trypsin seemed to be specific, since bacteriocin activity was not detected when R. gnavus E1 was cultivated in culture medium supplemented with other pancreas-secreted digestive proteolytic enzymes such as chymotrypsin, elastase, and carboxypeptidases A and B (36).

Because of its production by an intestinal bacterium and its activity against enteropathogenic clostridia, RumA may be of particular interest in animal feed and human health. Thus, the aim of this study was to gain insights into the genetic requirements for RumA biosynthesis and determine the regulatory mechanism involving trypsin. To this end, a 12.8-kb DNA fragment containing the RumA locus was cloned and sequenced, and its transcriptional organization was determined. The results reported here strongly suggest that trypsin is involved in a growth-dependent signal transduction pathway leading to the expression of the genes coding for RumA production and immunity. Trypsin-dependent biosynthesis of RumA thus represents an interesting example of bacterial adaptation to and recognition of a specific environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The RumA-producing strain R. gnavus E1 and the nonproducer strain R. gnavus ATCC 29149 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.), were grown in an anaerobic cabinet at 37°C in prereduced BHI-YH broth (BHI medium [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.] supplemented with 5 g of yeast extract [Difco Laboratories] and 5 mg of hemin [Sigma-Aldrich Chimie, St. Quentin Fallavier, France] per liter). When required, 50 μg of trypsin from bovine pancreas (type XIII, l-1-tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone [TPCK] treated; Sigma-Aldrich Chimie) per liter was added. The activity of trypsin in cultures was measured by using the synthetic substrate Nα-benzoyl-l-arginine p-nitroanilide hydrochloride (BAPNA; Sigma-Aldrich Chimie) as described by Midtvedt et al. (30). When necessary, trypsin was inactivated by the addition of 50 μg of type I-S trypsin inhibitor from soybean (Sigma-Aldrich Chimie) per ml, which specifically blocks the proteolytic activity of trypsin (2). When required, BHI-YH was supplemented with 500 μg of α-chymotrypsin from bovine pancreas (type VII, Nα-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone hydrochloride [TLCK] treated; Sigma-Aldrich Chimie) per ml, 80 μg of elastase from porcine pancreas (type IV; Sigma-Aldrich Chimie) per ml, or 160 μg of carboxypeptidase A from bovine pancreas (type II, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride treated; Sigma-Aldrich Chimie) per ml. Antibacterial activity was determined from a supernatant of the cultures by using an agar diffusion assay in solid BHI-YH as described by Ramare et al. (36). Activity was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution showing a clear zone of growth inhibition of the indicator strains Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 and/or Clostridium perfringens CpA (36) and was expressed in arbitrary units (AU) per milliliter.

DNA isolation and manipulation.

For the isolation of R. gnavus E1-chromosomal DNA, cells from a 100-ml overnight culture were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of TES buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, sucrose at 25%; pH 8.0) supplemented with lysozyme (20 mg ml−1) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Then, 600 μl of 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 10 μl of a proteinase K solution (20 μg μl−1) were added, and the cell suspension was incubated for 10 min at 50°C. Complete lysis was achieved by addition of 400 μl of 20% SDS and further incubation at 50°C until a clear lysate was obtained. The mixture was then extracted three consecutive times with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (75:20:5, 50:40:10, and 25:60:15) and one last time with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol only. After precipitation with isopropanol, the genomic DNA was resuspended in 1 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0) with 10 μg of RNase A. The solution was incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and the DNA was again precipitated by adding 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8) and 2 volumes of ice-cold ethanol. Finally, it was dissolved in 1 ml of TE. Established protocols were followed for molecular biology techniques (42). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, and other DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Life Technologies SARL, Eragny, France), MBI Fermentas (Vilnius, Lithuania), or Promega (Madison, Wis.) and used as recommended by the manufacturers.

Genomic library construction and analysis.

Partially Sau3AI-digested genomic DNA from R. gnavus E1 was size fractionated by differential sucrose gradient centrifugation (42), and DNA fragments ranging from 7 to 12 kb were ligated to λ-ZAP Express BamHI arms (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The ligated DNA was packaged by using the Gigapack III Gold Packaging Extract and transfected into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue MRF′ (both from Stratagene). The library was initially analyzed by hybridization with the γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide ol30 (Table 1), designated on the basis of a previously obtained partial sequence of the RumA structural gene (8). The molecular and microbiological techniques used to screen the library in this and further chromosome walking steps (plating, amplification, plaque lifting, hybridization, DNA isolation, etc.) were in accordance with standard procedures (42) and the recommendations of the supplier (Stratagene).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Primer (orientation)b | Sequence |

|---|---|

| ol30 (F) | 5′-AAAAACAATCAGCCACGAATGCAATATGAA-3′ |

| NrumR (R) | 5′-GTAATCAACGATACAGGTTTTGACGGATCC-3′ |

| NrumA (R) | 5′-TTCATATTGCATTCGTGGCTGATTGTTTTT-3′ |

| NrumM (R) | 5′-CAAGAACGCATAAATGCCTGTCAATCCGCA-3′ |

| NrumK (R) | 5′-CTAGCATAGTCTGCGGTGATTCTGAACCATAATCT-3′ |

| NrumF (F) | 5′-AGGGTCTAAACCGTTGGTCGGCTCATCCAA-3′ |

| N16S (R) | 5′-TGGAACTGTCAGGCTAGAGTGTCGGAGAGGAAA-3′ |

| rtR2 (F) | 5′-ATCTTCGAGACCGGATAGAATAATGAAAGG-3′ |

| rtF (R) | 5′-ACTGCTTTGCAATCTGGATTTGCTACTGAC-3′ |

| rtT1 (R) | 5′-ACCACTTCCCGAAACTCCTACGACAGCATA-3′ |

| rtM (F) | 5′-TTCAAAGTTGCACTCTGTTTTAATGCTTGAAACTG-3′ |

| rtX (R) | 5′-TCCGTCAAAGCATTCCAAAATATCCGAAATTCCTC-3′ |

| rtT2 (F) | 5′-TATGCTGTCGTAGGAGTTTCGGGAAGTGGTAAATC-3′ |

All of the primers were synthesized by Eurobio Laboratories, Les Ulis, France.

F, forward; R, reverse. Primers NrumA, NrumM, NrumK, NrumR, and NrumF were used as probes in transcriptional analyses of the corresponding rum genes.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

The inserts of the positive clones isolated from the library were sequenced on both strands by a primer-walking strategy with a ABI Prism 377 DNA automated sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.) and by using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer). Sequences were analyzed with the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group package (9).

Extraction of RNA and analysis by Northern and slot blot hybridization.

Total RNA was extracted from R. gnavus E1 by using an adaptation of the method described by Glatron and Rapoport (20). An overnight culture of E1 was diluted 1:100 in BHI-YH and grown to an established optical density at 600 nm (OD600) depending on the experiment. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of cold TE and transferred into a 2-ml screw-cap microcentrifuge tube containing 0.6 g of glass beads (0.1 mm in diameter; Sigma-Aldrich), 170 μl of 2% Macaloid slurry (42), 500 μl of water-saturated phenol-chloroform (1:1), and 50 μl of 10% SDS. Cells were disrupted by shaking in a Mini-Beadbeater-8TM Cell Disrupter (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) for 5 min. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min, the aqueous supernatant, which contained the RNA, was extracted with 1 volume of phenol-chloroform, precipitated with 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.0) and 3 volumes of ethanol, and finally resuspended in TE before storage at −80°C. The concentration and quality of the RNA were determined by measuring the A260 and A280 with a Beckman (Fullerton, Calif.) DU640 spectrophotometer and affirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Trace amounts of DNA in RNA samples were removed by treatment with DNase I Amp Grade (Gibco-BRL). For Northern blot analysis, 30 μg of total RNA was denatured by treatment with glyoxal, separated by electrophoresis through a 1% agarose gel, and transferred by capillary blotting to a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). For slot blot hybridization experiments, RNA samples were prepared as previously described by Stahl et al. (46) and modified by Dore et al. (12). The samples were transferred to nylon membranes using a PR600 Slot-Blot Filtration Manifold (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.). Membranes were reacted with γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotides complementary to the coding strand of different rum genes (Table 1). Hybridization was carried out overnight at 42°C in 50% formamide. For Northern analysis, the 0.28- to 6.58-kb and 0.24- to 9.5-kb RNA ladders from Promega and Gibco-BRL, respectively, were used as molecular size markers and visualized by staining of membranes with methylene blue (Sigma-Aldrich) (53).

RT-PCR.

cDNA synthesis was performed by reverse transcription (RT) of 2 μg of RNA primed with 20 pmol of different sequence-specific oligonucleotides. The reaction was carried out at 42°C for 1 h with the RevertAid H Minus M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (MBI-Fermentas) as recommended by the supplier. The enzyme was inactivated by heating for 10 min at 70°C, and 4 μl of the mixture was used directly as a template for the PCR amplifications. PCR reactions were performed in a 50-μl volume by using the TaKaRa LA Taq (Takara Shuzo Co., Otsu Shiga, Japan) under the following conditions: 94°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. As a control, additional reactions were performed by using as a template an RT mixture without enzyme, an RT mixture without RNA, and chromosomal DNA.

Induction assays.

Inducing activity was assayed by two different experiments. (i) A total of 5 ml of BHI-YH broth within a dialysis tubing of 10,000-molecular-weight (MW) cutoff (Dispodyalyseur Spectra Por from PolyLabo, Strasbourg, France) was inoculated with a 100-fold-diluted overnight culture of E1 and suspended in 200 ml of BHI-YH broth supplemented with 50 μg of trypsin ml−1. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C under anaerobic conditions, the bacteriocin activity was tested as indicated above. (ii) Conditioned medium was generated from a E1 culture grown to the late exponential phase (5 h of incubation; OD600 = 0.9) in BHI-YH broth supplemented with trypsin. Bacteria were removed by centrifugation, and trypsin was inactivated by the addition of Type I-S inhibitor from soybean to the supernatant. The supernatant was 10-fold concentrated in a Speed Vac Concentrator (Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, France) and sterilized by filtration with a low protein binding filter with 0.2-μm pore size (Millipore Co., Bedford, Mass.). Then, 1 ml of this concentrated-conditioned medium was added to 9 ml of an E1 culture growing without trypsin to an OD600 of 0.3, and the bacteriocin activity was tested 24 h after inoculation.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this study has been deposited in the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database (European Bioinformatics Institute, Hinxton, United Kingdom) under accession no. AJ276653.

RESULTS

Organization of the RumA biosynthesis gene cluster.

Genomic DNA of the E1 strain was digested with several restriction enzymes and analyzed by Southern hybridization by using the rumA specific primer ol30 as a probe (Table 1). Unique restriction DNA fragments hybridizing to the probe were identified (data not shown). A genomic library was constructed and screened as described in Materials and Methods, and the inserts of six overlapping clones were sequenced. The combined DNA sequence covered 12,802 bp with a G+C content of 32%. Based on computer analysis, this region comprised thirteen probable open reading frames (ORFs), which were tentatively named rum genes (Fig. 1). It should be noted that the proposed role of the different so-called rum genes in RumA production lacks direct experimental support and remains to be determined. Each ORF was preceded by potential ribosome binding sites and initiated by either an ATG, a GTG (rumT), or a TTG (rumR2) start codon.

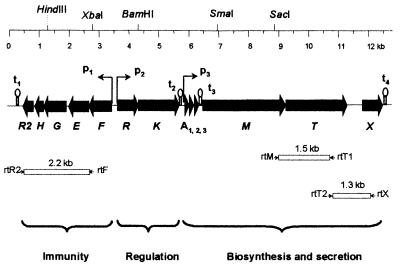

FIG. 1.

Organization of the RumA gene cluster. The arrows represent the different rum genes, and their orientation shows the transcriptional direction. Presumed functions of the three operons are indicated below. White boxes represent fragments amplified by RT-PCR with the indicated primers. p1, p2, and p3 are putative promoters; t1 to t4 are potential stem-loop structures that might act as rho-independent transcriptional terminators. Only unique restriction sites are shown.

The first five ORFs, rumFEGHR2, were oriented in the 3′ -to -5′ transcriptional direction relative to eight others. The putative product of rumF was a protein of 254 amino acids with a theoretical molecular mass of 28 kDa showing clear similarity with the ATP-binding domain of ABC transporters assumed to participate in lantibiotic immunity and toxin resistance (1, 5). The predicted proteins encoded by the two following ORFs, rumE and rumG were in turn similar to the membrane domains of this kind of transporter. RumE (222 amino acids, 24.5 kDa) and RumG (254 amino acids, 28.4 kDa) were similar to each other and showed well-conserved hydrophobicity profiles with predicted membrane-spanning segments (data not shown). Downstream of rumG, the sequence deduced from rumH corresponded to a hydrophobic protein of 98 amino acids and 10.8 kDa. It was similar to the product of an ORF found downstream of the rumEG counterparts in the butyrivibriocin OR79 locus (24). RumH also showed a certain similarity (40%) with the central hydrophobic region of SapC, a membrane component of the Sap transporter required for resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (33). Thus, RumFEGH peptides could constitute an ABC transport system involved in the self-protection of E1 against RumA. The next ORF, rumR2, encoded a 116-amino-acid protein (13 kDa) similar to unusual response regulators belonging to the CheY subfamily. Members of this group lack the C-terminal effector domain present in most response regulators and consist of a single phosphorylation domain (48). Downstream of rumR2, an inverted repeat predicted to form a stem-loop structure with ΔG = −12.3 kcal/mol (49), might act as a rho-independent transcription terminator.

Starting 149 bp upstream of the start codon of rumF, and in the opposite orientation, the gene rumR was predicted to encode a 233-amino-acid protein (26 kDa). RumR displayed a high degree of sequence similarity with the subfamily of OmpR-like response regulators of two-component systems. The N-terminal 123 amino acids of RumR was 38% similar to the deduced protein sequence of RumR2 (Fig. 2). Both proteins showed comparable hydrophobicity profiles (data not shown) and included conserved residues with structural and functional significance in the CheY-like phosphorylation domain of response regulators (52). The following downstream ORF, rumK, encoded a 459-amino-acid protein (52 kDa) with the typical features of an EnvZ-like sensor histidine kinase (48). The N terminus of RumK contained two hydrophobic membrane-spanning domains flanking a hydrophilic region of approximately 110 amino acids, which could be the extracellular sensor domain. The C-terminal part of the protein included several conserved regions and could be responsible for the intracellular transmission of signals by phosphorylation. An inverted repeat was located immediately downstream of rumK, possibly representing a rho-independent terminator with a calculated ΔG of −20.8 kcal/mol (49).

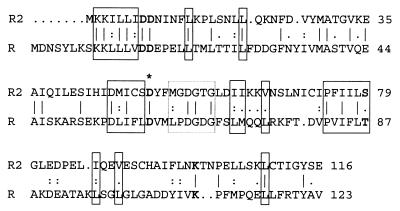

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the deduced protein sequences of RumR2 (R2) and the N-terminal region of RumR (R). Numbers on the right of figure refer to amino acid positions. Identical residues are indicated by vertical lines and similar residues are indicated by dots. According to the results of Volz (52), the five highly conserved residues known to constitute the active site of the CheY-like phosphorylation domain of response regulators are shown in boldface letters. The aspartate residues that could be phosphorylated in both proteins are indicated with an asterisk. Amino acids matching with conserved residues included in the hydrophobic core of the CheY-like domains are boxed. The dashed box (faint) encloses residues that could be included in the so-called γ-turn-loop, a conserved structural feature adjacent to the active site of the molecule.

The next ORFs, rumA1, rumA2, and rumA3, were three almost identical genes (96.4% nucleotide sequence identity between rumA1 and rumA2, 96.4% between rumA1 and rumA3, and 95.7% between rumA2 and rumA3). All of them encoded the same 47-amino-acid peptide, corresponding to the precursor of RumA. It was similar to prepeptides of known type AII lantibiotics with potential double-glycine (GG) leaders (Fig. 3). The spaces separating the rumA1-rumA2 and the rumA2-rumA3 genes were 17 and 18 bp, respectively, with both exhibiting 94% sequence identity. Downstream of the rumA genes, rumM was predicted to encode a protein (914 amino acids, 107.4 kDa) showing similarity with modification enzymes assumed to catalyze dehydration and thioether bridge formation of lantibiotic precursors (50). The following ORF, rumT, encoded a putative 688-amino-acid protein (77.2 kDa) exhibiting significant identity with dual-function ABC transporters involved in secretion and leader peptide-processing of lantibiotics and unmodified bacteriocins with a GG-type leader (21, 41). The N-terminal region of RumT contained the cysteine-protease domain characteristic of these proteins, including the conserved Cys residue. The product encoded by rumX (226 amino acids, 25.6 kDa), which starts 518 bp downstream of rumT, did not show obvious sequence similarity with known proteins. The N-terminal 130 amino acids of RumX displayed similarity with DNA-associated proteins, such as the DNA-replication helicase DNA2 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a putative DNA recombinase from Streptomyces coelicolor, and the subunit A of DNA-gyrase from Clostridium acetobutylicum (accession numbers P38859, CAB42047, and P94605). The C-terminal part of the protein was similar to limited stretches of a hemolysin-type calcium binding protein from Xylella fastidiosa and a hemagglutinin-hemolysin-related protein from Neisseria meningitidis (accession numbers AAF85544 and AAF42109).

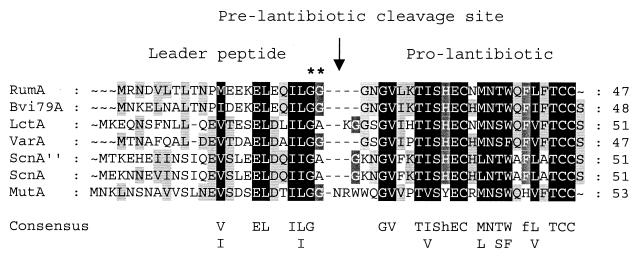

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the deduced peptide sequence for RumA precursor and homologous type-AII lantibiotics butyrivibriocin OR79A (Bvi79A), lacticin 481 (LctA), variacin (VarA), streptococcin A-M49 (ScnA″), streptococcin A-FF22 (ScnA), and mutacin II (MutA). Consensus residues are shown below. Identical residues are on a black background, and conserved substitutions are on a gray background. Dashes indicate gaps introduced during the alignment. The asterisks mark the double-glycine sequence motif immediately preceding the cleavage site of the type AII prelantibiotics (41). The total length of each protein is indicated on the right. Producer organisms and accession numbers for the sequences are as follows: Bvi79A (B. fibrisolvens), AF062647; LctA (L. lactis), U91581; VarA (M. varians), X93303; ScnA′′ (S. pyogenes), L36235; ScnA (S. pyogenes), AF026542; MutA (S. mutans), U40620.

Finally, two possible rho-independent transcriptional terminators with calculated ΔG values of −17.2 and −24.7 kcal/mol (49), were found downstream of rumA3 and rumX, respectively. Furthermore, the region immediately preceding the three rumA copies, as well as the intergenic region between rumF and rumR, contained possible promoter-like sequences and also a significant number of direct repeats which could play a regulatory role in promoter activity.

Transcription analysis of the rumA locus.

In order to determine the role of trypsin in RumA production and immunity, the transcription of the rum genes was investigated when the E1 strain was cultivated with or without trypsin. The non-RumA-producing strain, R. gnavus ATCC 29149, was used as a negative control. Northern analyses were performed on total RNA isolated from cells grown to the late exponential phase, and oligonucleotides designated on the basis of different rum genes were used as probes (Table 1). When total RNA from E1 was hybridized to the rumA genes probe, two transcripts were observed to be induced under trypsin conditions: a major transcript of 0.6 kb in length, which corresponded to the expected length of an mRNA containing the three rumA copies, and a minor one of approximately 7.0 kb (Fig. 4). This transcript was also recognized by a rumM probe, suggesting that rumM, as well as the downstream genes rumT and rumX, might be transcribed from the same promoter as rumA by limited readthrough to the terminator t3 (see Fig. 1). In the absence of trypsin, this operon was transcribed weakly, although the 7.0-kb mRNA was not observed, probably because its amount under noninducing conditions was below the level of detection of the Northern blot assay.

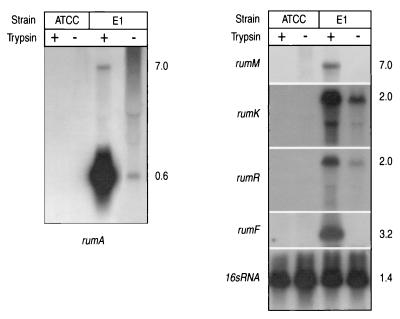

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of RumA locus transcription. Total RNAs isolated from R. gnavus E1 and from the nonproducing strain R. gnavus ATCC 29149, grown with (+) or without (−) trypsin, were hybridized separately with probes specific to the different rum genes (indicated in italics). In the lane corresponding to the hybridization of E1 RNA grown without trypsin to the rumA probe, the film was exposed for 24 h more than the other lanes of the same blot. Equivalent loading and transfer of RNA were verified by using N16S (Table 1), a specific probe for variable regions of the R. gnavus 16S rDNA (F. Marcille, unpublished results). Molecular sizes of the transcripts are indicated as kilobases to the right.

Independent hybridization of the E1 RNA to specific probes for rumK and rumR revealed a same-sized 2.0-kb mRNA, indicating that both genes were cotranscribed. Shorter bands of lower intensity were also observed, probably reflecting mRNA processing of the full-length 2.0-kb transcript, since no additional promoters could be detected downstream of the p2 promoter region. The amount of transcript of the rumRK operon was seen to increase in the presence of trypsin, suggesting that it was upregulated under these conditions. When a rumF probe was used, a transcript of 3.2 kb was detected only from the RNA of E1 cultivated with trypsin. Consistent with these data, strain E1 was sensitive to RumA when it was grown without trypsin and, therefore, when the mRNA containing rumF was not transcribed. Finally, and as expected, the RNA from the control strain, R. gnavus ATCC 29149, did not hybridize with any of the probes.

The results obtained by Northern analysis were confirmed by RT-PCR amplifications, which showed the transcriptional linkage of the genes within the predicted biosynthetic and immunity operons. Total RNA from both trypsin and non-trypsin conditions was independently reverse-transcribed with the primers rtR2, rtT1, and rtX (Table 1) specific to the genes rumR2, rumT, and rumX, respectively. The cDNAs thus generated were amplified by using the oligonucleotides pairs rtR2-rtF, rtT1-rtM, and rtX-rtT2 and the expected products of 2.2, 1.5, and 1.3 kb (see Fig. 1) were obtained only from RNA isolated from cells grown in the presence of trypsin. Control reactions containing RNA without reverse transcriptase or the enzyme but not RNA were negative.

All these results indicate that trypsin participates in the regulation of RumA production and immunity at the transcriptional level.

Growth-phase-dependent expression of rumA genes and regulation by trypsin.

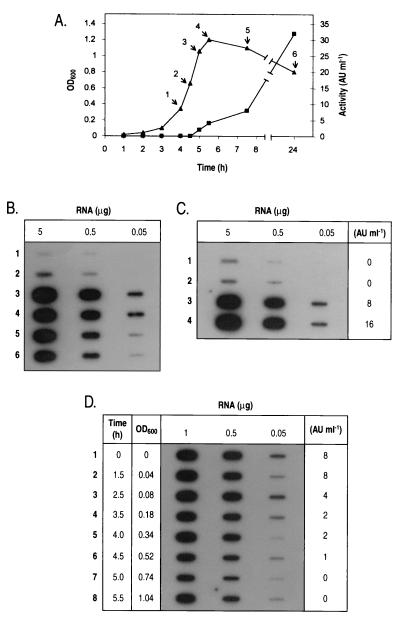

To determine the temporal distribution of rumA genes expression, slot blot analyses were performed on total RNA isolated over a 24-h time course from E1 cultures grown in liquid medium supplemented with trypsin. The rumA genes were weakly expressed in the first 4 h after inoculation. Transcription increased when bacteria reached at the mid-logarithmic phase (point 2 in Fig. 5A and B), with a maximum at 5 h of growth (point 3). Thereafter, the amount of the rumA transcript decreased slowly but remained substantial even after 19 h in stationary phase (point 6). This transcription pattern was well correlated with the detection of RumA activity in the culture supernatants, which started at 5 h and was maximal at 24 h of culture. These results suggest that RumA was continuously synthesized during stationary growth. As a control, an equivalent time course was performed from a non-trypsin-containing culture. As expected, no activity was detected at any time point and the initial basal transcription of the rumA operon remained unchanged throughout the growth curve (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Expression of rumA genes in E1 during cell growth and regulation by trypsin. (A) Time course for growth (OD600; ▴) and antibacterial activity against B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (AU ml−1; ▪) of E1 in a trypsin-supplemented medium. E1 was cultivated as described in Materials and Methods by diluting 100-fold a fresh overnight culture. Arrows indicate phases of growth at which samples were removed for determining bacteriocin activity, isolating total RNA, and performing trypsin inhibition tests. (B) Slot blot hybridization of the rumA probe to RNA isolated from E1 at different time points throughout growth. (C) Effect of the inactivation of trypsin at different stages of growth on rumA expression. For the first four time points indicated in the curve above, 10 ml of the culture was harvested and, after inhibition of trypsin activity, samples were grown to the early stationary phase. Total RNA was then isolated and hybridized to the rumA probe, and the bacteriocin activity (expressed as AU per milliter) was determined in culture supernatants. (D) Effect of the addition of trypsin at different growth phases on rumA expression. A fresh overnight culture of E1 was 100-fold diluted and further separated into 10-ml batch cultures. The cultures were supplemented with trypsin at different stages of growth, represented on the left of the figure as times after inoculation along with the corresponding OD600. When trypsin-supplemented cultures reached the early stationary phase, total RNA was isolated and subsequently hybridized to the rumA probe, and the bacteriocin activity (expressed as AU per milliliter) was determined in supernatants.

To try to understand the role of trypsin in the observed cell density-dependent activation of the rumA operon, transcriptional analyses were performed from samples where trypsin had either been inactivated or added at different stages of growth.

For the trypsin inactivation experiment, the samples were recovered from the early to post-exponential phases of the same E1 culture represented in Fig. 5A (points 1 to 4). The proteolytic activity of trypsin was blocked by addition of specific soybean inhibitor, and the expression of rumA genes was evaluated in each sample when cells reached the early stationary phase (Fig. 5C). When trypsin activity was inhibited at stages 1 and 2 (early and mid-exponential phases, respectively), almost no rumA transcripts could be detected at the end of growth, indicating that transcription of rumA genes had not been induced. Consequently, no RumA activity was detected in the supernatant of these cultures. These results suggested that the induction of rumA expression occurring after the mid-exponential phase of growth (see Fig. 5B) was dependent on the proteolytic activity of trypsin. On the other hand, inhibition of trypsin activity at stages 3 and 4 (late and post-exponential phases, respectively) did not have a significant effect on rumA expression, suggesting that once the transcription was triggered, trypsin activity was no longer necessary.

In a second experiment, trypsin was added to E1 batch cultures at successive stages of growth, so as to mimic a curve similar to that represented in Fig. 5A. rumA expression was further analyzed when cultures attained the early stationary phase (Fig. 5D). The addition of trypsin at any time point throughout the first 4 h of culture (lanes 1 to 5) allowed full induction of rumA gene transcription, although the bacteriocin activity of samples appeared to decrease progressively. Therefore, the presence of trypsin before the early exponential phase was not essential for activating rumA expression. In contrast, rumA transcript was less abundant when trypsin was added from the mid- to post-exponential phases (4.5 to 5.5 h after inoculation), causing a loss in detectable antimicrobial activity and suggesting that trypsin action was less effective when cells were in the second half of the exponential growth. The relatively higher amount of rumA transcript detected in the culture at which trypsin had been added at the post-exponential phase (lane 8) was probably due to an incorrect quantification of the RNA concentration in the sample.

Taken together, these studies demonstrated that the transcription of the rumA operon was strictly regulated through a growth-dependent mechanism needing the proteolytic activity of trypsin during, at least, the first half of the exponential growth. Considering what is documented on cell-density-dependent regulation in gram-positive bacteria, it was conceivable that trypsin activity could modulate a specific growth-accumulated signal responsible for triggering rumA expression after the mid-logarithmic phase. The products of the rumRK operon, likely constituting a two-component system, were the obvious candidates for regulating rumA transcription in response to the putative trypsin-dependent signal. If true, the observed upregulation of this operon by trypsin (see Fig. 4) must occur sooner than the burst of rumA transcription. To test this possibility, the expression of the rumRK operon was monitored during growth by hybridizing the total RNA previously isolated over the time course represented in Fig. 5A to the rumK probe. Transcription of the rumRK genes appeared to peak at the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (point 2), remained high until the end of this stage, and subsequently declined during post-exponential and stationary growth (results not shown).

Induction of bacteriocin production.

Induction assays were performed to test the hypothesis that RumA production could be triggered by a trypsin-activated extracellular signal. Bacteriocin activity (32 AU ml−1) was detected in an E1 culture incubated in a dialysis tubing plunged into trypsin-supplemented medium. As expected, at the end of the experiment trypsin activity was found in the external medium but not inside the tubing (trypsin MW = 23,500 and dialysis tubing MW cutoff = 10,000). These results suggested that the inducer was a molecule of MW <10,000, produced and secreted by R. gnavus E1 during growth. It was presumably a protein, since induction of RumA production was shown to be dependent on the proteolytic activity of trypsin. Furthermore, direct contact between bacteria and trypsin was not necessary, indicating that the inducer was not cell wall associated.

In a second induction assay, conditioned medium was obtained, as described in Materials and Methods, from an E1 culture grown with trypsin to the late exponential phase. When supplied to a non-trypsin-containing E1 culture, conditioned medium was able to induce RumA production, since the bacteriocin activity (8 AU ml−1) was detected in the supernatant of supplemented culture after 24 h of incubation. A control, in which conditioned medium was added to fresh BHI-YH broth and subsequently incubated for 24 h, did not show bacteriocin activity. Hence, conditioned medium could contain the putative trypsin-activated inducer peptide at a sufficient concentration to trigger RumA biosynthesis under conditions without trypsin.

Control assays were also performed with spent media generated from (i) a late-exponential-phase culture of E1 grown without trypsin and from (ii) BHI-YH broth supplemented with trypsin. In this latter case and to reproduce the same conditions used to generate the conditioned medium described above, trypsin was inactivated with the soybean inhibitor after 5 h of incubation at 37°C in anaerobic conditions. None of these spent media showed RumA-inducing activity when added to a non-trypsin-containing E1 culture. These results first confirmed that induction activity was dependent on trypsin. Second, they demonstrated that the putative inducer peptide was not derived from either the hydrolysis of a growth medium protein or the eventual autolysis of trypsin. Consequently, one can conclude that the inducer was produced by the E1 strain itself as an extracellular molecule.

The production of the trypsin-dependent inducer was shown to be strain specific, since conditioned medium obtained from a late-exponential-phase trypsin-supplemented culture of the non-RumA-producing strain R. gnavus ATCC 29149 did not show any inducing activity.

In order to test whether purified RumA could induce its own synthesis, as in the case of nisin or the RumA-homologous lantibiotic salivaricin A (27, 51), decreasing amounts of protein were added to non-trypsin E1 cultures at final concentrations ranging from 200 to 1 ng ml−1. No activity was detected from RumA-supplemented cultures after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. The same result was obtained when a partially purified sample of RumA was used at final concentrations ranging from 1.5 μg ml−1 to 2 ng ml−1, indicating that neither RumA nor any other putative initially copurified peptides was the inducer triggering bacteriocin production.

Effect of other digestive proteases on induction of RumA production.

As previously mentioned, trypsin cannot be replaced by other digestive proteolytic enzymes for inducing bacteriocin production in liquid culture medium (36). To verify whether the specificity of trypsin action was at the transcriptional level, total RNA was obtained from R. gnavus E1 growing independently in BHI-YH supplemented with α-chymotrypsin, elastase, or carboxypeptidase A (500, 80, and 160 μg ml−1, respectively). The concentration of each protease was consistent with enzymatic activities measured in rat pancreatic secretions (18, 36). Slot blot hybridization of RNA samples to the rumA-specific probe showed that, contrary to trypsin, these proteases were not able to induce the transcription of rumA genes (data not shown).

The effect of proteases on trypsin-dependent inducing activity was also investigated, by using the dialysis tubing assay described above. Three E1 cultures, respectively containing 500 μg of α-chymotrypsin, 80 μg of elastase, or 160 μg of carboxypeptidase A per ml, were independently incubated for 24 h in a dialysis tubing plunged into trypsin-supplemented BHI-YH broth. Interaction between tested proteases and trypsin was not possible since their MW values were higher than dialysis tubing cutoff (MW = 10,000). Antimicrobial activity was not detected in any case, indicating that such digestive proteases negatively affected trypsin-induced bacteriocin production.

In order to determine whether the observed effect was due to proteolytic degradation of the putative produced bacteriocin, an E1 culture supernatant exhibiting antimicrobial activity was treated with each of the proteases under the same conditions used in the dialysis tubing test (concentrations indicated above; 24 h of anaerobic incubation at 37°C). Such a treatment did not abolish bacteriocin activity, suggesting that α-chymotrypsin, elastase, and carboxypeptidase A could inhibit the induction of RumA production, perhaps by degrading the putative trypsin-activated inducer peptide.

DISCUSSION

In this work, a 12.8-kb fragment from the genome of R. gnavus E1, containing the genetic determinants of RumA production, was characterized. The average G+C content of the RumA locus is 32%, significantly lower than that of R. gnavus E1 chromosomal DNA (43% G+C; F. Gavini, unpublished data). This fact suggests the possibility of horizontal transfer of DNA from an organism with a lower G+C composition. On the basis of similarity comparisons with other well-characterized AII-lantibiotic gene clusters, 13 ORFs with proposed functions in RumA biosynthesis, secretion, regulation, and immunity were identified.

Interestingly, the precursor peptide of RumA seems to be encoded by three consecutive structural genes, rumA1, rumA2, and rumA3. The presence of two structural genes in some AII-lantibiotic gene clusters has already been reported (4, 22, 31, 40) but, in contrast to the rumA genes, they code for two distinct peptides constituting the subunits of the active bacteriocin. The high percentage of nucleotide sequence identity displayed by rumA copies and their intergenic regions (>94%) suggests that gene rearrangement occurred, leading to the triplication of the ancestral structural gene. A similar event has been reported for the RumA-homologous lantibiotic streptococcin A-M49 (23). Two tandem copies of the structural gene, encoding precursors that differ in some amino acids of the leader sequence, are present in this case. Gene duplications are a common evolutionary response in bacteria exposed to different selective pressures (6, 39). Some duplications have been shown to be advantageous under selective conditions, and they may play a prominent role in the adaptation of microorganisms to the environment (38, 44, 54). One of the best examples is the amplification of the Vibrio cholerae toxin genes during intestinal growth in rabbits (29). Thus, the triplication of the RumA-structural gene in the E1 strain suggests that these genes could confer an adaptive advantage to this bacterium.

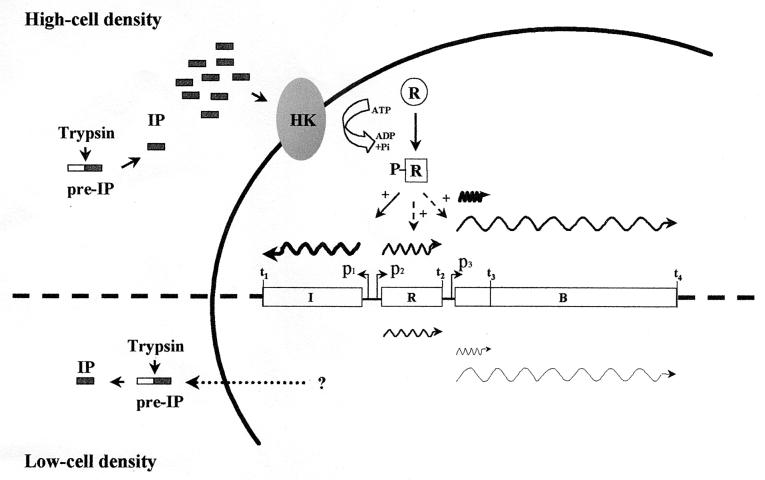

Transcriptional analyses revealed that the RumA locus is organized into three operons whose expression is induced by trypsin. The transcription of the putative regulatory operon rumRK is increased when trypsin is present but is constitutive under noninducing conditions. This finding is consistent with a potential role of RumK and RumR as the sensor and effector components, respectively, of a signal transduction mechanism. Otherwise, no proteins would be available to receive the signal triggering the system into an activated state. On the other hand, the three rumA copies can be transcribed as an operon also containing the downstream genes rumM, rumT, and rumX. However, our results demonstrate that most transcripts initiated at the rumA promoter terminate at the junction between rumA3 and rumM, likely at the stem-loop structure named t3. The stem-loops located downstream of the structural gene are conserved in many lantibiotic gene clusters and are considered to function as transcriptional attenuators or as sites protecting the structural-gene mRNA against exonuclease degradation (34, 41). This organization could ensure that biosynthetic enzymes are present in limited and catalytic amounts in relation to the precursor substrate. Under trypsin-deficient conditions, the rumA operon is weakly transcribed. This expression does not produce inhibitory concentrations of RumA detectable in culture supernatants. Likewise, E1 tolerates the produced bacteriocin, although the putative immunity operon is not transcribed under these conditions. The expression of the immunity machinery only when massive production of RumA is induced would represent an advantage for the cell, which could conserve energy for bacteriocin synthesis until a certain threshold level was reached. In addition, trypsin-induced expression of the immunity operon could also play a regulatory role in RumA biosynthesis, since rumR2 is cotranscribed along with the proposed immunity genes rumFEGH. Recently, the regulation of lacticin 3147 immunity by LtnR, a transcriptional repressor encoded in the same operon as the immunity proteins, has been reported (28). LtnR negatively regulates the expression of its own operon when sufficient amounts of encoded proteins are accumulated within the cell. Nevertheless, RumR2 cannot act as a transcriptional regulator because it does not contain a DNA-binding output domain. Consequently, its participation in regulation, if any, is likely to be indirect. Although it seems still premature, one hypothesis is that RumR2 could modulate the ratio between the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of the other response regulator, RumR. In a signal transduction pathway, the strength, and sometimes also the nature, of the response ultimately depends on balancing opposed reactions of phosphorylation (activation) and dephosphorylation (inactivation) of the effector by the sensor (32). This dynamic switch allows continuous adaptation of the cellular response to a changing environment. If we assume that both RumR and RumR2, whose shared conserved motifs are characteristic of the response regulator phosphorylation domain, are phosphorylated by the histidine kinase RumK, RumR2 could act as a phosphate sink, accelerating the decrease in RumR-P concentration and thereby contributing to response decay once the synthesis of RumA has been triggered. A similar role has been proposed for CheY1 in the chemotactic response of Sinorhizobium meliloti (45) and Helicobacter pylori (17). Thus, the level of expression of the immunity operon and, therefore, the intracellular concentration of RumR2 may serve as an internal signal, allowing bacteria to maintain a steady state in bacteriocin production and E1 self-resistance.

We have demonstrated that the trypsin-mediated induction of RumA production is growth phase regulated. Transcription of the rumA structural genes strongly increases between the mid- and late logarithmic stages, and these RNAs are still abundant even after 19 h of incubation in the stationary phase, corresponding well to RumA production kinetics. Not all lantibiotics show this correlation: mutacin II, a RumA-homologous lantibiotic, is expressed independently of the growth stage, whereas it is only produced at the end of the exponential phase (35). The burst of rumA transcription is preceded by the increased expression of the operon encoding the two-component system RumRK, supporting the idea that the production of RumA is directly regulated by this system. Growth-dependent systems have been shown to control the production of nonmodified bacteriocins (7), as well as that of some lantibiotics such as nisin (16), subtilin (26), and mersacidin (1). Since bacteriocins are active against species closely related to the producing organisms, cell density-dependent regulation of their production could be important from an ecological point of view (14). The sensing of its own growth could be an indicator for the bacteriocin-producing bacteria of the related species. Thus, inducible production of an antimicrobial activity would confer a selective advantage over other bacteria sharing the same ecological niche when competition for resources increases. In the case of RumA synthesis, the control of this mechanism by trypsin supports the idea that this antimicrobial activity could play a role in bacterial interactions taking place in the gut ecosystem and suggests a high adaptation of the RumA-producing strain to its natural environment.

Taking into account the results obtained in transcriptional studies and induction assays, we proposed a model explaining the growth-phase-dependent regulation of RumA production (Fig. 6; see the legend for more details). According to this model, a trypsin-activated inducer peptide (IP) could act as the signal leading to the expression of rum genes. Such an IP could reach the threshold concentration required for induction after the mid-exponential phase of growth. Induction seems to depend on the timely accumulation of the IP, since R. gnavus E1 become less sensitive for trypsin-mediated switching of RumA production in the late logarithmic phase. This phenomenon has already been reported by Eijsink et al. (15) for the induction of bacteriocin production in L. sake LTH673, which is described as an “all-or-nothing” process.

FIG. 6.

Hypothetical model for the trypsin-induced growth-dependent activation of the RumA locus in R. gnavus E1. At the early stages of growth, low-level constitutive transcription from the p2 and p3 promoters gives rise to the basal expression of the operons encoding the two-component regulatory system, the unmodified RumA-precursor and the biosynthetic proteins. We suggest that, at the same time, a putative inducer peptide (IP) is synthesized and exported by the cell as an inactive precursor, pre-IP. Proteolytic processing of pre-IP by trypsin can lead to the accumulation of the active form (IP) in the culture medium during growth. When a certain threshold concentration of the IP is reached, the signal transduction pathway is triggered. The interaction of the IP with the external domain of the histidine kinase RumK finally induces the phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic regulator protein RumR, which in turn stimulates the transcription of the immunity operon and also amplifies the expression of the regulatory and biosynthetic operons. In the absence of trypsin, the pre-IP is not processed and, consequently, the signal triggering the growth-dependent regulatory mechanism is not effective. Hence, the transcription pattern of the RumA locus remains unchanged during growth. In the figure, wavy lines represent the positions and sizes of the transcripts. Their thickness reflects the relative amounts, as judged from Northern blotting (Fig. 3). White boxes represent the immunity (I), regulatory (R), and biosynthetic (B) operons. Promoter activation is indicated by “+”. Dashed arrows represent the amplification of transcription from p2 and p3.

The specificity of the induction mechanism described in this model suggests that R. gnavus E1 has found a way to sense its own cell density, as well as to recognize its natural environment. Evidences supporting the influence of environment on the regulation of bacteriocins production had been reported (7, 10) but, to our knowledge, this is the first example showing how an environmental factor could modulate the regulatory circuit controlling bacteriocin biosynthesis. Nevertheless, considering the complexity of the gut ecosystem, the effectiveness of such a regulation pathway in vivo is likely dependent on the interrelation of multiple environmental parameters. The results presented here suggest that trypsin-dependent induction of RumA production could be inhibited by other digestive proteases, but the in vivo significance of such an action is uncertain. Proteases have been assayed at concentrations found in secretions of rat pancreas, since trypsin had been shown to induce bacteriocin production in culture medium only at pancreatic concentrations (36). However, enzymatic activities measured in the terminal part of intestinal tract, which harbors most of the microbiota, can be highly variable. Pancreatic enzymes undergo a progressive inactivation by both host and bacterial factors during their passage through the entire intestine (3, 19, 37). The concentration of trypsin required for the in vivo production of an antimicrobial substance by R. gnavus E1 appears to be much lower than that supplied by pancreas (36), but the impact of other proteolytic activities remains to be elucidated under physiological conditions.

Regarding the nature of the putative inducer peptide, we do not have enough information to date. The initial low-level transcription of the RumA biosynthetic operon first led us to think that it could contain the gene encoding the precursor of the inducer peptide. Cell density-dependent regulation in gram-positive bacteria implies that the inducer is initially produced at a low, constitutive level. Thus, it is accumulated during growth and, once a threshold concentration has been crossed, a positive feedback circuit quickly generates a burst of the signal, as well as a rapid density-dependent response (13, 25). Moreover, inducer peptides controlling bacteriocin production are commonly encoded by genes belonging to the bacteriocin gene cluster (25). Among the biosynthetic proteins, only the putative product from rumX might be considered as the possible preinducer, since we have demonstrated that RumA is not able to activate its own synthesis. However, this does not seem probable. The C-terminal region of the peptide is similar to hemolysin-related proteins, but no putative secretory signal was found in the RumX sequence. In addition, RumX has a theoretical molecular mass of 25.6 kDa, and induction experiments using dialysis tubing indicate that the secreted preinducer is not greater than 10 kDa. Thus, the role played by RumX in RumA biosynthesis remains unclear.

Further studies are now needed, particularly concerning the characterization of the putative trypsin-activated inducer, and the role of other intestinal-ecosystem factors in the in vivo regulation of bacteriocin production. This could help us to improve our understanding of how bacteria interact within the gut in response to environmental information and maybe also open the way to host-controlled expression of beneficial functions. One question to elucidate is whether trypsin regulates more than just RumA production. Other bacterial functions belonging to such a hypothetical trypsin regulon could be investigated, and their potential impact on colonization and/or colonization resistance could be evaluated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants “Actions Concertées Coordonnées Sciences du Vivant” from the French Ministry for Research and Technology, “FAIR CT 95-0433” from the European Community, and “Prix de Projet de Recherche Alimentation et Santé 1999” from the Danone Institute.

We thank Bertrand Nicolas for technical support and Anne Marie Wall and Geraldine Rigou for revising the manuscript. We also thank Ludovic Le Chat and Mark Chippaux for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altena, K., A. Guder, C. Cramer, and G. Bierbaum. 2000. Biosynthesis of the Lantibiotic mersacidin: organization of a type B lantibiotic gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2565–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birk, Y. 1976. Trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors from soybeans. Methods Enzymol. 45:700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohe, M., A. Borgstrom, S. Genell, and K. Ohlsson. 1983. Determination of immunoreactive trypsin, pancreatic elastase and chymotrypsin in extracts of human feces and ileostomy drainage. Digestion 27:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth, M. C., C. P. Bogie, H. G. Sahl, R. J. Siezen, K. L. Hatter, and M. S. Gilmore. 1996. Structural analysis and proteolytic activation of Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin, a novel lantibiotic. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1175–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, V., T. Hundsberger, P. Leukel, M. Sauerborn, and C. von Eichel-Streiber. 1996. Definition of the single integration site of the pathogenicity locus in Clostridium difficile. Gene 181:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, C. J., K. M. Todd, and R. F. Rosenzweig. 1998. Multiple duplications of yeast hexose transport genes in response to selection in a glucose-limited environment. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15:931–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brurberg, M. B., I. F. Nes, and V. G. Eijsink. 1997. Pheromone-induced production of antimicrobial peptides in Lactobacillus. Mol. Microbiol. 26:347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dabard, J., C. Bridonneau, C. Phillipe, P. Anglade, D. Molle, M. Nardi, M. Ladire, A. Gomez, and M. Fons. 2001. Ruminococcin A, a new lantibiotic produced by a Ruminococcus gnavus strain isolated from human feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4111–4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diep, D. B., L. S. Havarstein, and I. F. Nes. 1996. Characterization of the locus responsible for the bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. J. Bacteriol. 178:4472–4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diep, D. B., O. Johnsborg, P. A. Risoen, and I. F. Nes. 2001. Evidence for dual functionality of the operon plnABCD in the regulation of bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum. Mol. Microbiol. 41:633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dore, J., A. Sghir, G. Hannequart-Gramet, G. Corthier, and P. Pochart. 1998. Design and evaluation of a 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe for specific detection and quantitation of human faecal Bacteroides populations. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunny, G. M., and B. A. Leonard. 1997. Cell-cell communication in gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:527–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dykes, G. A. 1995. Bacteriocins: ecological and evolutionary significance. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10:186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eijsink, V. G., M. B. Brurberg, P. H. Middelhoven, and I. F. Nes. 1996. Induction of bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus sake by a secreted peptide. J. Bacteriol. 178:2232–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelke, G., Z. Gutowski-Eckel, P. Kiesau, K. Siegers, M. Hammelmann, and K. D. Entian. 1994. Regulation of nisin biosynthesis and immunity in Lactococcus lactis 6F3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:814–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foynes, S., N. Dorrell, S. J. Ward, R. A. Stabler, A. A. McColm, A. N. Rycroft, and B. W. Wren. 2000. Helicobacter pylori possesses two CheY response regulators and a histidine kinase sensor, CheA, which are essential for chemotaxis and colonization of the gastric mucosa. Infect. Immun. 68:2016–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genell, S., B. E. Gustafsson, and K. Ohlsson. 1976. Quantitation of active pancreatic endopeptidases in the intestinal contents of germfree and conventional rats. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 11:757–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson, S. A., C. McFarlan, S. Hay, and G. T. MacFarlane. 1989. Significance of microflora in proteolysis in the colon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:679–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glatron, M. F., and G. Rapoport. 1972. Biosynthesis of the parasporal inclusion of Bacillus thuringiensis: half-life of its corresponding messenger RNA. Biochimie 54:1291–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havarstein, L. S., D. B. Diep, and I. F. Nes. 1995. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol. Microbiol. 16:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holo, H., Z. Jeknic, M. Daeschel, S. Stevanovic, and I. F. Nes. 2001. Plantaricin W from Lactobacillus plantarum belongs to a new family of two-peptide lantibiotics. Microbiology 147:643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hynes, W. L., V. L. Friend, and J. J. Ferretti. 1994. Duplication of the lantibiotic structural gene in M-type 49 group A streptococcus strains producing streptococcin A-M49. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4207–4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalmokoff, M. L., D. Lu, M. F. Whitford, and R. M. Teather. 1999. Evidence for Production of a new lantibiotic (butyrivibriocin OR79A) by the ruminal anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens OR79: characterization of the structural gene encoding butyrivibriocin OR79A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2128–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleerebezem, M., L. E. Quadri, O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1997. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal-transduction systems in gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 24:895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein, C., C. Kaletta, and K. D. Entian. 1993. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic subtilin is regulated by a histidine kinase/response regulator system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuipers, O. P., M. M. Beerthuyzen, P. G. de Ruyter, E. J. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27299–27304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAuliffe, O., T. O’Keeffe, C. Hill, and R. P. Ross. 2001. Regulation of immunity to the two-component lantibiotic, lacticin 3147, by the transcriptional repressor LtnR. Mol. Microbiol. 39:982–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mekalanos, J. J. 1983. Duplication and amplification of toxin genes in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 35:253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Midtvedt, T., B. Carlstedt-Duke, T. Hoverstad, A. C. Midtvedt, K. E. Norin, and H. Saxerholt. 1987. Establishment of a biochemically active intestinal ecosystem in ex-germfree rats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2866–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navaratna, M. A., H. G. Sahl, and J. R. Tagg. 1999. Identification of genes encoding two-component lantibiotic production in Staphylococcus aureus C55 and other phage group II S. aureus strains and demonstration of an association with the exfoliative toxin B gene. Infect. Immun. 67:4268–4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkinson, J. S. 1995. Genetic approaches for signaling pathways and proteins, p. 9–23. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Parra-Lopez, C., M. T. Baer, and E. A. Groisman. 1993. Molecular genetic analysis of a locus required for resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 12:4053–4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen, C. 1992. Control of functional mRNA stability in bacteria: multiple mechanisms of nucleolytic and non-nucleolytic inactivation. Mol. Microbiol. 6:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi, F., P. Chen, and P. W. Caufield. 1999. Functional analyses of the promoters in the lantibiotic mutacin II biosynthetic locus in Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramare, F., J. Nicoli, J. Dabard, T. Corring, M. Ladire, A. M. Gueugneau, and P. Raibaud. 1993. Trypsin-dependent production of an antibacterial substance by a human Peptostreptococcus strain in gnotobiotic rats and in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2876–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy, B. S., J. R. Pleasants, and B. S. Wostmann. 1969. Pancreatic enzymes in germfree and conventional rats fed chemically defined, water-soluble diet free from natural substrates. J. Nutr. 97:327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riehle, M. M., A. F. Bennett, and A. D. Long. 2001. Genetic architecture of thermal adaptation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth, J. R., N. Benson, T. Galitski, K. Haack, J. G. Lawrence, and L. Miesel. 1996. Rearrangements of the bacterial chromosome: formation and applications, p. 2256–2276. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 2. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 40.Ryan, M. P., R. W. Jack, M. Josten, H. G. Sahl, G. Jung, R. P. Ross, and C. Hill. 1999. Extensive post-translational modification, including serine to d-alanine conversion, in the two-component lantibiotic, lacticin 3147. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37544–37550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahl, H. G., and G. Bierbaum. 1998. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:41–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 43.Siezen, R. J., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Comparison of lantibiotic gene clusters and encoded proteins. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 69:171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sonti, R. V., and J. R. Roth. 1989. Role of gene duplications in the adaptation of Salmonella typhimurium to growth on limiting carbon sources. Genetics 123:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sourjik, V., and R. Schmitt. 1998. Phosphotransfer between CheA, CheY1, and CheY2 in the chemotaxis signal transduction chain of Rhizobium meliloti. Biochemistry 37:2327–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stahl, D. A., B. Flesher, H. R. Mansfield, and L. Montgomery. 1988. Use of phylogenetically based hybridization probes for studies of ruminal microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1079–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stock, J. B., M. G. Surette, M. Levit, and P. Park. 1995. Two-component signal transduction systems: structure-function relationships and mechanisms of catalysis, p. 25–51. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 49.Tinoco, I., Jr., P. N. Borer, B. Dengler, M. D. Levin, O. C. Uhlenbeck, D. M. Crothers, and J. Bralla. 1973. Improved estimation of secondary structure in ribonucleic acids. Nat. New Biol. 246:40–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uguen, P., J. P. Le Pennec, and A. Dufour. 2000. Lantibiotic biosynthesis: interactions between prelacticin 481 and its putative modification enzyme, lctM. J. Bacteriol. 182:5262–5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Upton, M., J. R. Tagg, P. Wescombe, and H. F. Jenkinson. 2001. Intra- and interspecies signaling between Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus pyogenes mediated by SalA and SalA1 lantibiotic peptides. J. Bacteriol. 183:3931–3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volz, K. 1995. Structural and functional conservation in response regulators, p. 53–64. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 53.Wilkinson, M., J. Doskow, and S. Lindsey. 1991. RNA blots: staining procedures and optimization of conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamanaka, K., L. Fang, and M. Inouye. 1998. The CspA family in Escherichia coli: multiple gene duplication for stress adaptation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]