Abstract

The degradation of 3-oxoadipate in Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 was investigated and was shown to proceed through 3-oxoadipyl-coenzyme A (CoA) to give acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA. 3-Oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase of strain B13 was purified by heat treatment and chromatography on phenyl-Sepharose, Mono-Q, and Superose 6 gels. Estimation of the native molecular mass gave a value of 115,000 ± 5,000 Da with a Superose 12 column. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions resulted in two distinct bands of equal intensities. The subunit A and B values were 32,900 and 27,000 Da. Therefore it can be assumed that the enzyme is a heterotetramer of the type A2B2 with a molecular mass of 120,000 Da. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of both subunits are as follows: subunit A, AELLTLREAVERFVNDGTVALEGFTHLIPT; subunit B, SAYSTNEMMTVAAARRLKNGAVVFV. The pH optimum was 8.4. Km values were 0.4 and 0.2 mM for 3-oxoadipate and succinyl-CoA, respectively. Reversibility of the reaction with succinate was shown. The transferase of strain B13 failed to convert 2-chloro- and 2-methyl-3-oxoadipate. Some activity was observed with 4-methyl-3-oxoadipate. Even 2-oxoadipate and 3-oxoglutarate were shown to function as poor substrates of the transferase. 3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase was purified by chromatography on DEAE-Sepharose, blue 3GA, and reactive brown-agarose. Estimation of the native molecular mass gave 162,000 ± 5,000 Da with a Superose 6 column. The molecular mass of the subunit of the denatured protein, as determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, was 42 kDa. On the basis of these results, 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase should be a tetramer of the type A4. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase was determined to be SREVYI-DAVRTPIGRFG. The pH optimum was 7.8. Km values were 0.15 and 0.01 mM for 3-oxoadipyl-CoA and CoA, respectively. Sequence analysis of the thiolase terminus revealed high percentages of identity (70 to 85%) with thiolases of different functions. The N termini of the transferase subunits showed about 30 to 35% identical amino acids with the glutaconate-CoA transferase of an anaerobic bacterium but only an identity of 25% with the respective transferases of aromatic compound-degrading organisms was found.

Many bacteria are able to grow with chloroaromatics via chlorocatechols as the central intermediates.

Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 was one of the first organisms shown to be able to grow with a chloroaromatic compound (10) and is an interesting model organism. Various aspects of the degradation have been studied in detail with strain B13: the intermediates of the pathways (11, 60), the enzymes involved (59), and the specificities of the enzymes (11, 29, 68) plus their potential for elimination of chlorine substituents (29, 59). In addition, the genetic information encoding the enzymes of the modified ortho cleavage pathway was the subject of investigation (16, 27, 67), as well as the property of conjugal transfer of the appropriate genes into other hosts, which allowed the formation of so-called hybrid pathways allowing the resulting strain to use additional chlorinated substrates not used by the parent organisms of a mating (51–54). Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 has also been used as a host of external genes introduced by in vitro techniques (33, 55). Because of these results strain B13 and its derivatives have been chosen as model organisms in studies on the clean-up of soils contaminated with chloroaromatics (6, 14, 19, 22) and in environmental studies (34, 40, 73).

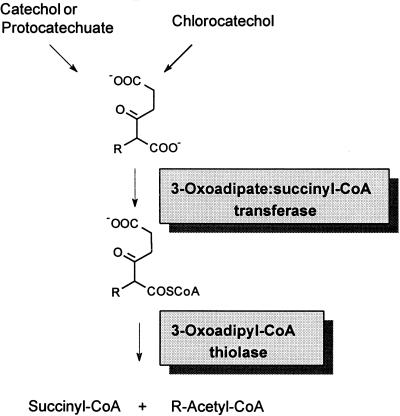

In the present paper we studied enzymes 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA) transferase and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13, which are necessary to reach the Krebs cycle after the convergence of pathways used for the degradation of aromatic and chloroaromatic compounds (Fig. 1). In the accompanying paper the respective genes are the subject of investigation (18). For comparison some data from the purified transferases of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Pseudomonas putida (71) as well as data on the genes encoding these enzymes were available. In contrast, enzyme data on 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase were absent, while a mass of gene data on various types of bacterial and mammalian thiolases are accessible.

FIG. 1.

Convergence of degradation pathways for aromatic and chloroaromatic compounds. R = H, degradation of catechol, protocatechuate, and 3-chloro-, 4-chloro-, 3,5-dichloro-, and 3,6-dichlorocatechol; R = Cl, degradation of 3,4-dichloro- and 3,4,6-trichlorocatechol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism and culture conditions.

Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 (DSMZ6978) was grown at 30°C with mineral medium containing 3-chlorobenzoate (10 mM), benzoate (10 mM), or acetate (10 mM) as the substrate (10). For enzyme purifications 6 liters of 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells was harvested in the late-exponential growth phase by centrifugation.

Preparation of cell extracts.

Cells were resuspended in buffer A (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). Disruption was performed at 4°C by one passage through a French pressure cell (140 MPa; American Instruments Co., Silver Spring, Md.). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C.

Enzyme assays.

3-Oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase (EC 2.8.3.6) was measured by a modification of the method of Katagiri and Hayaishi (30). The assay mixture contained 35 μmol of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 25 μmol of MgC12, 3.5 μmol of 3-oxoadipate, and 0.15 μmol of succinyl-CoA in a total volume of 1 ml. After addition of the enzyme (crude extract or a preparation from the purification), the increase of absorbance at 305 nm (corresponding to the formation of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex) was measured. The extinction coefficient of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex (ɛM) of 16,300 M−1 cm−1 was determined in this study using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of CoA, succinyl-CoA, and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA.

3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase was assayed by determining the decrease of absorbance at 305 nm of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex due to the addition of CoA. After a period of 15 min for the in situ preparation of the complex with the purified 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase, 0.2 μmol of CoA and the enzyme (crude extract or a preparation from the purification; 0.02 to 0.2 mg of protein) were added.

ATP- and CoA-dependent 3-oxoadipate-activating enzyme activity was assayed in a coupled reaction with thiolase in crude extract by determining the increase of concentration of acetyl-CoA using HPLC. The assay mixture contained 35 μmol of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 25 μmol MgC12, 3.5 μmol of 3-oxoadipate, 0.2 μmol of CoA, and 0.2 μmol of ATP in a total volume of 1 ml. The reaction was started by adding crude extract of B13 (0.02 to 0.2 mg of protein).

3-Oxoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase (EC 3.1.1.24) was assayed as described by Ornston (41). The assay mixture contained (in 1 ml) 30 μmol of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 0.5 μmol of muconolactone, and 20 μl of isomerase (prepared by heat treatment at 55°C for 30 min of P. putida A3.12 crude extract as described by Ornston [42]). After 5 min the decrease of absorbance at 230 nm (ɛM = 2,050 M−1 cm−1) was measured. The reaction was initiated by addition of crude extract of B13 (0.02 to 0.2 mg of protein).

Dienelactone hydrolase (EC 3.1.1.45) was measured at 280 nm as described by Schlömann et al. (58) by determining the decrease of substrate concentration. Reaction mixtures contained (in 1 ml) 10 μmol of histidine-HCl buffer (pH 6.5) and 0.1 μmol of cis-dienelactone. The reaction was started by adding crude extract of B13 (0.02 to 0.2 mg of protein).

One unit is defined as the activity required to convert 1 μmol of substrate or to form 1 μmol of product per min under the conditions of the assay at 25°C.

Kinetic measurements.

The pH optima were determined between pH 7 and 9 using Tris-HCl buffer. For that, a relative ɛM of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex was determined for each pH value.

For testing the influence of inhibitors on the transferase activity, a sample of diluted pure enzyme stock solution was preincubated for 10 min at 20°C in 35 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, containing 25 mM MgCl2 and 3.5 mM 3-oxoadipate in the presence of the reagent. The reaction was started by adding succinyl-CoA to obtain a concentration of 0.15 mM in the mixture.

Thiolase inhibition was studied as follows. A 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex (0.07 mM) was prepared by using purified transferase (35 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8, containing 25 mM MgCl2) followed by incubating thiolase for 5 min at 20°C in the presence of the reagent. The reaction was started by adding CoA (0.2 mM) to the assay mixture.

The activity of transferase with 2-oxoadipate and 3-oxoglutarate was measured by determining the concentration of the CoA-ester formed with HPLC assuming that the levels of extinction of the respective CoA-esters are identical for all CoA-esters under investigation. Activity is given relative to the activity with 3-oxoadipate (100%).

Enzyme purification.

All procedure steps were carried out at 4°C.

(i) 3-Oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase. (a) Step 1: heat treatment.

Sampled crude extracts (25 ml) were heated to 59°C for 15 min. Precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected, and the pellet was extracted with 3 ml of buffer A1 (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 mM EDTA) and centrifuged again.

(b) Step 2: ammonium sulfate treatment and chromatography on phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B.

Solid (NH4)2SO4 was added in small portions with constant stirring to the combined supernatant and with washing as described in step 1 to give 75% saturation. After 30 min the precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min. The pellet was redissolved with buffer B1 (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 1 M [NH4]2SO4 and 1 mM EDTA) to a final volume of 30 ml. The solution was cleared by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant, containing transferase activity, was applied at 0.5 ml/min to a phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B gel column (1.6 by 20 cm) preequilibrated with buffer B1. After the column was washed with 150 ml of buffer B1, 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase was eluted with 30 ml of buffer A1 in a linear gradient of (NH4)2SO4 from 1 to 0 M. Fractions of 2 ml were collected at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Ten fractions (20 ml in total) containing the highest levels of activity were pooled.

(c) Step 3: ion exchange chromatography on Mono-Q.

The pooled fractions from step 2 were desalted by ultrafiltration (molecular weight [MW], 10,000) and applied at 0.3 ml/min to a Mono-Q column (0.5 by 5 cm; HR5/5; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) which had been preequilibrated with buffer A1. After the column was washed with 10 ml of buffer A1 at 0.5 ml/min, transferase was eluted with 20 ml of buffer A1 containing NaCl in a linear gradient from 0 to 1 M. Fractions of 0.25 ml were collected at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Four fractions (1 ml in total) containing the highest levels of activity were pooled.

(d) Step 4: gel filtration on Superose 6.

Combined fractions from step 3 were concentrated to 0.2 ml by ultrafiltration (MW, 30,000). The concentrate was applied to a Superose 6 column (1 by 30 cm) that had previously been equilibrated with buffer C (150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM KCl and 1 mM EDTA). The flow rate was maintained at 0.4 ml/min, and fractions of 0.2 ml were collected. Ten fractions (2 ml in total) containing the highest levels of activity were pooled.

(e) Step 5: storage.

The combined fractions from step 4 were concentrated to 1 ml by ultrafiltration (MW, 10,000), and glycerol was added to a total volume of 2 ml. This pure enzyme stock solution was stored at −20°C.

3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase. (a) Step 1: DEAE-Sepharose chromatography.

Five milliliters of crude extract (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0) was diluted with 25 ml of Tris-HCl (10 mM, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 mM DTT) to a final concentration of 25 mM Tris-HCl and applied at 1 ml/min to a DEAE-Sepharose column (2.5 by 17 cm) preequilibrated with buffer A2 (25 mM, pH 7.0, containing 0.5 mM DTT). After the column was washed with 175 ml of buffer A2, the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase was eluted with 90 ml of buffer A2 containing KCl in a linear gradient from 0 to 1 M. Fractions of 6 ml were collected at a flow rate of 3 ml/min. Six fractions (36 ml in total) containing the highest levels of activity were pooled, desalted, and concentrated to a final volume of 3.1 ml by centrifugal filtration (Centriplus 100; Amicon, Beverly, Mass.).

(b) Step 2: blue 3GA.

The pooled and desalted fraction of step 1 were applied at 0.25 ml/min to a reactive blue 3GA column (1 by 11 cm) which had been preequilibrated with buffer A2. After the column was washed with 30 ml of buffer A2, thiolase was eluted with 100 ml of buffer A2 containing KCl in a linear gradient from 0 to 1 M. Fractions of 1 ml were collected at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Nine fractions (9 ml in total) containing the highest levels of activity were pooled, desalted, and concentrated to a final volume of 1.4 ml by centrifugal filtration (Centriprep 100; Amicon).

(c) Step 3: reactive brown.

The pooled and desalted fractions of step 2 were applied at 0.25 ml/min to a reactive brown column (1.6 by 11 cm) preequilibrated with buffer A2. The column was washed with 70 ml of buffer A2, followed by elution of the thiolase with 100 ml of buffer A2 containing KCl in a linear gradient from 0 to 1 M. Fractions were collected at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. Seven fractions (14 ml in total) were pooled, desalted, concentrated, and transferred in buffer A by centrifugal filtration (Centriprep 50 and Microcon 50; Amicon) to give a final volume of 120 μl.

(d) Step 4: storage.

The final enzyme solution was added to 120 μl of glycerol and stored at −20°C.

Determination of Mr values.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was used to determine the subunit Mr values and the purity of the 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase. It was performed by the method of Laemmli (32) on 1-mm-thick vertical-slab gels (13.5 by 15.5 cm) containing 12.5% (wt/vol) acrylamide in the resolving gels. Electrophoresis was performed at a voltage of 100 V for 1 h and 200 V for 6 h. The apparatus was cooled to 4°C. Proteins were detected by staining the gels with silver (37) or with Coomassie blue. The calibration proteins were bovine albumin (Mr, 66,000), chicken ovalbumin (Mr, 45,000), porcine stomach pepsin (Mr, 34,700), trypsinogen (Mr, 24,000), bovine β-lactoglobulin (Mr, 18,400), and bovine α-lactalbumin (Mr, 14,200) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). The Mr value of the native protein was determined by means of gel filtration on a Superose 12 fast protein liquid chromatography column (1 by 30 cm) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The column buffer was 150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 100 mM NaCl. Horse ferritin (Mr, 443,000), sweet potato β-amylase (Mr, 200,000), yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (Mr, 150,000), bovine albumin (Mr, 67,000), chicken ovalbumin (Mr, 45,000), chymotrypsinogen A (Mr, 25,000), and horse cytochrome c (Mr, 12,500) were used as the reference proteins (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Standards and samples were injected in 100-μl portions, and the proteins were detected by monitoring the eluate at 254 nm.

N-terminal amino acid sequencing and data search.

About 10 μg of each purified enzyme (transferase or thiolase) was applied to an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (1.5 mm thick) and separated. The separated polypeptides representing the subunit(s) of transferase or thiolase were blotted onto an Amersham Hybond polyvinylidene difluoride membrane according to the Amersham protocol (staining was done with amido black). The N-terminal amino acid sequences were determined with an Applied Biosystems model 477A protein sequencer and an Applied Biosystems model 120A on-line high-performance liquid chromatograph according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

The N-terminal sequences were compared to protein sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant database (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by using BLAST, version 2.0.4.

Analytical methods. (i) HPLC.

The transferase activity was subsequently assayed by direct quantification of decrease and formation of CoA derivatives, according to a modified method described previously by Corkey et al. (8). This procedure involved measurement of individual compounds by reverse-phase HPLC (Merck-Hitachi chromatograph system). Separations were achieved on an analytical SC column (125 by 4.6 mm; 100 RP18, 5.0 μm; LiChrospher, Bischoff, Germany) by elution with 10 mM potassium phosphate, buffered at pH 5.7, in water containing 8% (vol/vol) methanol at a flow rate of 1 ml per min. The column effluent was monitored by measuring the absorption at 260 nm, which corresponds to the UV maxima of CoA, succinyl-CoA, 3-oxoadipyl-CoA, acetoacetyl-CoA, and acetyl-CoA. The molecular extinction coefficients of all these compounds are in the same range due to the shared chromophore.

The retention times of the CoA-esters (acetyl-CoA, 2.83; succinyl-CoA, 1.14; 3-oxoadipyl-CoA, 1.25; 2-oxoadipyl-CoA, 1.72; 3-oxoglutaryl-CoA, 0.71) are given relative to the time measured with CoA as the standard (set to 1.0).

(ii) Spectroscopy.

Mass spectrometry (MS) data were obtained on a Varian MAT311A mass spectrometer. The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded with a Bruker ARX400MHz spectrometer in d-chloroform, d6-acetone, d4-methanol solution. Chemical shifts (δ) are in parts per million relative to that for tetramethylsilane as the standard.

(iii) GC-MS.

Products were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC)-MS (type HP 5890 gas chromatograph, type HP 5970 mass spectrometer with an HP-5 Hewlett-Packard column [30 m by 0.32 mm, 0.25-μm-thick film]). The column oven was heated from 30°C at the start (hold for 3 min) to a final temperature of 280°C at a rate of 10°C/min. The flame ionization temperature was 300°C.

(iv) Chloride.

Chloride was determined by the silver chloride method as described by Freier (17).

(v) Protein determination.

Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit as described by Bradford (5), with crystalline bovine serum albumin as the standard. During the enzyme purification, the eluted protein was detected with a Pharmacia UV-1 monitor at 254 nm.

Chemicals.

cis,cis-Muconic acid was synthesized by the peracetic acid oxidation of catechol as described by Kaschabek and Reineke (28). Dienelactones and enelactones were prepared by a Wittich reaction of maleic anhydride or succinic anhydride as described by Kaschabek and Reineke (29). Synthesis of chloroacetyl-CoA was achieved as described by Simon and Shemin (62) using chloroacetic anhydride. Racemic (±)-muconolactone was prepared from cis,cis-muconic acid by H2SO4 treatment as described by Elvidge et al. (13). Conversion of muconolactone to 3-oxoadipate enol-lactone was achieved with isomerase of P. putida A3.12 as described by Ornston (42). Methyl- or chlorosubstituted 3-oxoadipates were prepared in situ by NaOH or NaHCO3 hydrolysis of the respective enelactone. Alternatively, alkaline hydrolysis of the respective dienelactone using NaHCO3 or NaOH followed by a maleylacetate reductase-catalyzed reaction or step-by-step enzymatic conversion with crude extract was used for the preparation of the 3-oxoadipates.

CoA, succinyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, acetoacetyl-CoA, 2-oxoadipate, and 3-oxoadipate were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). All other chemicals were purchased commercially and were of the highest available purity.

RESULTS

Degradation of 3-oxoadipate.

Different routes have been reported to function in the degradation of 3-oxoadipate and substituted analogs in microorganisms. In bacteria and the yeast Trichosporon cutaneum 3-oxoadipyl-CoA was shown to be formed from 3-oxoadipate in a succinyl-CoA-dependent reaction (30, 50). In contrast, 4-methyl-3-oxoadipate is the subject of a reaction which needs CoA plus ATP as the cofactors in T. cutaneum (49). In both organisms thiolysis of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA and 4-methyl-3-oxoadipyl-CoA follows to give acetyl-CoA and (methyl)succinyl-CoA. It has been claimed that Neurospora crassa, on the other hand, degrades 3-oxoadipate by a route that involves CoA but that is hydrolytic rather than thiolytic, with acetate and succinate as the products (43). To decide conclusively whether the succinyl-CoA-dependent or the CoA- and ATP-dependent system is functioning in strain B13, the separation of the activating and the cleaving enzymes was performed.

In former times both enzyme activities were determined by measuring the formation or the disappearance of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex at 305 nm using the extinction coefficient obtained with acetoacetyl-CoA. To have a clear-cut proof of the enzyme tests, we used HPLC detection of CoA esters by analogy to the method of Armengaud et al. (3). Since the optical test was thought to fail with substrates with substitutions in the 2 position, probable end product chloroacetyl-CoA was synthesized to include it as a standard.

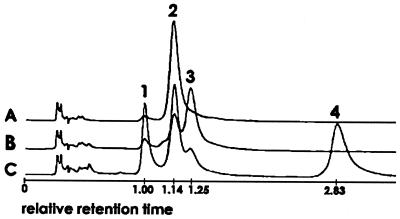

Degradation of 3-oxoadipate by crude extract of 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells of strain B13 with succinyl-CoA was shown by the increase of absorption at 305 nm (data not shown). The further addition of CoA resulted in the rapid disappearance of the species absorbing at 305 nm and the formation of acetyl-CoA, indicating a thiolytic fission. The thioesterfication of either of the carboxylic groups of 3-oxoadipate could occur in principle. The structure of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA is assigned on the basis of data which show that the formation of equimolar amounts of acetyl-CoA and some succinyl-CoA is due to thiolytic fission (Fig. 2). The biological formed substrate meets the structural requirements for this reaction. The enzymes involved in the degradation of 3-oxoadipate in strain B13 are a 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase and a 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase.

FIG. 2.

HPLC chromatograms of CoA derivatives involved in the degradation of 3-oxoadipate. Compounds: 1, CoA (peak at 6.7 min); 2, succinyl-CoA (peak at 7.6 min); 3, 3-oxoadipyl-CoA (probably, peak at 8.4 min); 4, acetyl-CoA (peak at 19.0 min). Chromatograms of assay: A, at start; B, after transferase reaction; C, after transferase and thiolase reaction.

Using an HPLC analysis plus the optical test system a ɛM at 305 nm of 16,300 M−1 cm−1 at pH 8 was obtained; this value is on the same order as the coefficient for the acetoacetyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex used for the enzyme assay in the past, 25,000 M−1 cm−1. Overall, conversions with crude extract and separated, purified enzymes showed identical results concerning products formed.

In addition to the succinyl-CoA-dependent transferase, some activity on 3-oxoadipate was observed with the above crude extract when ATP and CoA instead of succinyl-CoA were added. This was shown by the presence of acetyl-CoA, determined by HPLC as the result of activation of 3-oxoadipate followed by the thiolytic cleavage of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA (data not shown).

Presence of enzymes of the lower pathway in Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 during growth with different substrates.

Levels of activity of the enzymes of the lower pathway in cells of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 harvested during late-exponential growth on acetate, benzoate, and 3-chlorobenzoate were determined (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Induction of enzymes of the 3-oxoadipate and modified ortho cleavage pathway in Pseudomonas sp. strain B13

| Enzyme | Sp act (U/g of protein) in cells grown with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Benzoate | 3-Chloro-benzoate | |

| Dienelactone hydrolase | 15 | 15 | 720 |

| 3-Oxoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase | naa | 160 | 280 |

| 3-Oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase | <1 | 156 | 113 |

| CoA- and ATP-dependent 3-oxoadipate-activating enzyme | na | 20 | 13 |

| 3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase | na | 324 | 370 |

na, no activity.

The dienelactone hydrolase, a representative enzyme of the chlorocatechol pathway, is detectable at low levels in acetate-grown cells, while 3-oxoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase, 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase, and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase are absent. No activity was found when crude extract of acetate-grown cells was tested for CoA- and ATP-dependent activation of 3-oxoadipate.

In benzoate-grown cells the enzymes of the 3-oxoadipate pathway, 3-oxoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase, 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase, and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase, as well as the CoA- and ATP-dependent enzyme activity are highly induced. In benzoate-grown cells no induction of dienelactone hydrolase higher than the basal level was determined.

In 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells dienelactone hydrolase was present at levels of about 50-fold above the basal level. The levels of the enzymes of the “normal” 3-oxoadipate pathway are high in benzoate- and 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells. A comparison of the activity of the succinyl-CoA-dependent reaction with that of the CoA- and ATP-dependent one indicated the higher involvement of the transferase in the degradation of 3-oxoadipate. Because of these data we decided to purify the enzyme systems which are ATP independent, i.e., 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase.

3-Oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase. (i) Purification of the transferase.

3-Oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase was purified to homogeneity from 3-chlorobenzoate-grown Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 cells. The results are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Purification of the 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13

| Purification step | Vol (ml) | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg of protein) | Recovery of activity (%) | Purification factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 25 | 394 | 106 | 0.27 | 100 | 1 |

| Heat-treated supernatant | 25 | 77.5 | 103 | 1.33 | 97 | 4.9 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B, combined eluant | 20 | 30.8 | 101 | 3.28 | 95 | 12.1 |

| Mono-Q, combined eluant | 1 | 3.1 | 67 | 21.6 | 63 | 80 |

| Superose 6, combined eluant | 2 | 1.8 | 43 | 23.9 | 41 | 88.5 |

During purification the specific activity of the enzyme increased to 23.9 U of protein/mg, which is in the same range as the activities published for P. putida and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (71). This indicates an 88-fold purification with 41% recovery of activity. Since the enzyme was found to be stable at temperatures up to 60°C for several minutes, a property that has been reported for the transferase of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (30, 71), a great amount of protein was removed by heat treatment to 59°C as the first purification step. In the subsequent protein separation by hydrophobic interaction chromatography on phenyl-Sepharose enzyme activity was eluted at less than 0.1 M (NH4)2SO4. The protein elution during the following Mono-Q chromatography was observed at 0.3 M NaCl. During the final gel filtration on a Superose 6 column the protein was eluted as a single symmetrical protein peak exactly corresponding to the enzyme activity. The determination of the transferase by SDS-PAGE showed two protein bands of equal intensities (data not shown). During the purification only one transferase activity peak was observed in the chromatograms, indicating the presence of only one transferase in B13 cells grown with 3-chlorobenzoate.

(ii) Structural properties.

The molecular masses of the two subunits of the denatured protein, as determined by SDS-PAGE, were 32.9 (subunit A) and 27 kDa (subunit B). By analytical gel filtration chromatography of the purified protein with a Superose 12 column a molecular mass of 115 kDa was estimated. On the basis of these results, 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase should exist as a type A2B2 heterotetramer.

The N-terminal amino acid sequences of 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase were as follows: subunit A, AELLTLREAVERFVNDGTVALEGFTHLIPT; subunit B, SAYSTNEMMTVAAARRLKNGAVVFV. Sequence analysis of the N-terminal amino acid sequences of both subunits with protein sequences deduced from known CoA transferase genes showed only low identity. Subunit A was 40% identical to subunit A of the glutaconate-CoA transferase of anaerobic fermenting organism Acidaminococcus fermentans (36). Identities to 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferases of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (CatI) and of P. putida (PcaI) were 32 and 28%, respectively (20, 45).

Subunit B was 44% identical to the respective subunit of the glutaconate-CoA transferase of Acidaminococcus fermentans but was only 16% identical to the transferases of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (CatJ) and P. putida (PcaJ). Acetoacetyl-CoA:butyrate-CoA transferase of Clostridium acetobutylicum (ClosTr) showed 32% identical positions (48).

(iii) Inhibition and activation.

The effects of various compounds on the activity of 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase were determined. Chelating agents, such as EDTA or o-phenanthroline (1 mM), had no effect on enzyme activity. No significant requirement for the usual bivalent metal ions seems to exist, since the activity of the enzyme remained unchanged upon addition of cyanide ions (1 mM).

An inhibitory effect of heavy-metal derivative p-chloromercuribenzoate and HgCl2 on the activity of the transferase could not be determined, since addition of both compounds to 3-oxoadipyl-CoA solution resulted in the rapid destruction of the thioester (data not shown), a fact formerly reported by Powlowski and Dagley (49) for CoA and by Allred (2) for reduced glutathione.

Minor inhibition was observed with NADH: the remaining activity was 72% with 0.8 mM NADH.

(iv) pH optimum.

The dependence of the reaction rate on pH showed a curve with a pH optimum at 8.4.

(v) Kinetic data.

Km values were 0.4 and 0.2 mM for 3-oxoadipate and succinyl-CoA, respectively. On the basis of the subunit A plus B molecular mass of 59,900 Da, the catalytic constant is 1,430 min−1. Acetyl-CoA cannot replace succinyl-CoA as the CoA donor. The same is true for acetoacetate, 2-oxoglutarate, and 2-oxohexanoate, which failed to function as acceptor compounds. However, 2-oxoadipate showed some inhibition of the conversion of 3-oxoadipate (at 2.5 mM, remaining activity was 62%; at 5 mM, remaining activity was 42%). Interestingly, some very low activities were observed with 2-oxoadipate and 3-oxoglutarate; these activities were in the range of only 0.01 to 0.02% compared to that for the reaction with 3-oxoadipate, as measured by HPLC analysis. In contrast, adipate and 2-oxocaproate were not converted.

The transferase reaction was found to be reversible: the addition of succinate to the assay mixture brought about a decrease of 2absorption at 305 nm of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA-Mg2+ complex (data not shown).

3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase. (i) Purification of the thiolase.

3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase was purified from 3-chlorobenzoate-grown Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 cells. The results are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Purification of the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13

| Purification step | Vol (ml) | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg of protein) | Recovery of activity (%) | Purification factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 5 | 126 | 49 | 0.39 | 100 | 1 |

| DEAE-Sepharose | 3.1 | 20.7 | 27 | 1.3 | 54 | 3.3 |

| Reactive blue 3GA | 1.35 | 9.5 | 15 | 1.58 | 30 | 4 |

| Reactive brown | 0.12 | 0.36 | 4 | 11.1 | 8 | 28 |

In contrast to the transferase, the thiolase was labile at 60°C. In addition, the enzyme was sensitive to high concentrations of (NH4)2SO4—in the presence of 75% saturation the activity was reduced by more than 40%—so its purification has to be separate from that of the transferase.

3-Oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 was highly purified by chromatography on DEAE-Sepharose, blue 3GA, and reactive brown. Analysis by SDS-PAGE revealed only one major protein band at 42 kDa and two minor bands (data not shown). Attempts to eliminate this minor impurity were not performed. Gel filtration of the final preparation gave a single symmetrical peak under nondenaturing conditions. During the purification only one thiolase peak was observed in the chromatograms, indicating the presence of only one thiolase in B13 cells grown with 3-chlorobenzoate.

(ii) Structural properties.

Estimation of the native molecular mass value gave 162,000 ± 5,000 Da with a Superose 6 column. The molecular mass of the subunit of the denatured protein, as determined by SDS-PAGE, was found to be 42 kDa. On the basis of these results, 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase should be a homotetramer of the type A4.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase was determined to be SREVYI-DAVRTPIGRFG.

Sequence analysis of the 17-amino-acid sequence with the translated protein sequence encoded by known 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase genes of P. putida (21), Rhodococcus opacus (15), and a Streptomyces sp. (26) and acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase genes of Escherichia coli (1) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (72) showed high similarity, with 70 to 82% identical positions.

(iii) Inhibition and activation.

The effects of various compounds on the activity of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase were determined with a homogeneous enzyme. Chelating agents, such as EDTA and o-phenanthroline (1 mM), had no effect on enzyme activity. The remaining activity with CuSO4 (1 mM) was 10%, and with NaCN (1 mM) it was 88%, while ZnCl2 (1 mM) brought about 46% inhibition.

For the inhibitory effect of HgCl2 and p-chloromercuribenzoate see above.

NADH brought about the following inhibition: remaining activity was 90 and 58% with 0.4 and 0.8 mM, respectively.

(iv) pH optimum.

The dependence of the reaction rate on pH showed a curve with a pH optimum at 7.8.

(v) Kinetic data.

Km values were 0.15 and 0.01 mM for 3-oxoadipyl-CoA and CoA, respectively. On the basis of the subunit molecular mass of 42,000 Da, the catalytic constant is 470 min−1.

Determining the specificity of transferase and thiolase for substituted 3-oxoadipates and CoA-esters. (i) Preparation and characterization of substrates.

2-Chloro- and 4-chloro-3-oxoadipate, the compounds of interest as the metabolites in the degradation of 3,4-dichloro- and 3,4,6-trichlorocatechol, are not available. In addition, methyl-substituted 3-oxoadipates as substrate analogs were of interest. Attempts to synthesize chloro- or methyl-substituted 3-oxoadipate derivatives by chemical methods failed. However, two types of compounds are available from chemical synthesis as precursor compounds for the in situ preparation of 3-oxoadipates, substituted enelactones and dienelactones. Base-catalyzed hydrolysis (NaOH) of enelactone produced a compound which was a substrate for the B13 transferase. The hydrolysis of cis-dienelactone, either by dienelactone hydrolase of strain B13 or base (OH−) catalysis followed by transformation by B13-maleylacetate reductase, resulted in the same compound.

In contrast, 2-chloro-3-oxoadipate is unstable since about 10% was found to be subject to nucleophilic elimination of the chlorine substituent and formation of a hydroxyl derivative when a shift of pH to >8 with NaOH was tested to open 5-chloro-enelactone. The product, 2-hydroxy-3-oxoadipate, was identified by its decarboxylation product, 5-hydroxy-4-oxopentanoic acid methylester, as described by Lüönd et al. (35), by MS after acidification of the solution and extraction with ethyl acetate, followed by methylation with diazomethane and separation by GC. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ (parts per million) data are as follows: 4.14 (s, 2H, RCH2OH), 3.69 (s, 3H, ROCH3), 2.90 [t, 2H, R1CH2CH2R2, 3J(H,H) = 6.6 Hz], 2.67 [t, 2H, R1CH2CH2R2, 3J(H,H) = 6.6 Hz]. 13C-NMR (1H) (CDCl3) δ (parts per million) data are as follows: 201.2 (C-4), 172.7 (C-1), 68.2 (C-5), 51.9 (OCH3), 32.8 (C-3), 27.5 (C-2). GC-MS m/z (percent intensity) data are as follows: 143 (5), 129 (8), 125 (7), 115 (93) [M+-CH2OH], 113 (4), 97 (4), 87 (16) [M+-COCH2OH and M+-CO2CH3], 69 (8), 59 (87) [COCH2OH and CO2CH3], 56 (11), 55 (100) [M+-CH2OH, -CO2CH3, -H], 53 (6), 45 (47), 43 (13), 42 (24), 39 (14).

Opening of the lactone ring of 5-chloro-enelactone under acidic conditions as an alternative procedure led to the decarboxylation of the product formed. The product was identified as chloroacetoacetate methylester by MS and NMR after acidification of the solution and extraction with ethyl acetate, followed by methylation with diazomethane. The data are identical to those published by Montforts et al. (39), Sander et al. (56), and Segat-Dioury et al. (61) for 5-chloro-4-oxopentanoic acid methylester. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ (parts per million) data are as follows: 4.11 [s, 2H, R(CO)CH2Cl], 3.65 (s, 3H, CH3OR), 2.87 [t, 2H, CH2Cl(CO)CH2CH2R, 3J(H,H) = 6.4 Hz], 2.63 [t, 2H, CH2Cl(CO)CH2CH2R, 3J(H,H) = 6.4 Hz]. 13C-NMR (1H)-NMR (CDCl3) δ (parts per million) data are as follows: 201.2 (C-4), 172.7 (C-1), 51.8 (OCH3), 48.1 (C-5), 34.3 (C-3), 27.8 (C-2). MS m/z (percent intensity) data are as follows: 135 (34)/133 (96) [M+-OCH3], 116 (16), 115 (91) [M+-CH2Cl], 114 (15), 87 (26) [M+-COCH2Cl], 79 (23)/77 (78) [COCH2Cl], 59 (100) [CO2CH3], 55 (91) [M+-CH2Cl, -CO2CH3, -H], 51 (14)/49 (42) [CH2Cl+], 45 (52).

Dechlorination and decarboxylation were absent when an equimolar amount of NaHCO3 was used for ring opening. These data indicated that careful ring opening of substituted enelactones with NaHCO3 or the two-step enzyme-catalyzed conversion of substituted dienelactones are suitable methods to produce the respective 3-oxoadipate.

The hydrolysis of 2,3-dichlorodienelactone by dienelactone hydrolase followed by transformation with maleylacetate reductase took place in situ. However, the resulting compound, 4-chloro-3-oxoadipate, was found to be chemically unstable so that a chemical analysis was not carried out.

Conversion of substituted 3-oxoadipates.

When 2-chloro-3-oxoadipate, formed either by careful ring opening of 5-chloro-enelactone with NaHCO3 or from 5-chlorodienelactone by conversion with dienelactone hydrolase or NaHCO3 hydrolysis followed by a maleylacetate reductase reaction, was tested, formation of neither a CoA-Mg2+ complex at 305 nm nor an additional compound in the HPLC chromatogram occurred when the purified transferase plus succinyl-CoA were added. The same was true when crude extract of B13, containing transferase and thiolase, plus CoA, the substrate for thiolysis, were added to the solution: no peak of an additional CoA-ester or chloroacetyl-CoA occurred in the HPLC chromatograms. Similarly, no additional CoA-ester was observed by HPLC when the complex assay mixture, crude extract, 5-chlorodienelactone, NADH, succinyl-CoA, and CoA, was supplemented with ATP. The same was true for the rapid, complex assay when 5-chlorodienelactone was replaced by 2,3-dichlorodienelactone, which in principle should be converted via 4-chloro-3-oxoadipate.

We tested 2-chloro-3-oxoadipate and both 2-hydroxy-3-oxoadipate and 5-chloro-4-oxopentanoate for their ability to function as inhibitors of the transferase reaction. All three compounds showed an uncompetitive type of inhibition (data not shown), which indicates the absence of entrance of the compounds into the catalytic site.

The transferase also failed to bring about conversion of 2-methyl-3-oxoadipate. In contrast, 4-methyl-3-oxoadipate was found to be a poor substrate: acetyl-CoA was detected when crude extract or transferase plus thiolase was added to the assay mixture, indicating that both the transferase and thiolase exhibit activity with the respective metabolite.

From these data we conclude that the further conversion of 2-chloro- and 4-chloro-3-oxoadipate by the transferase of strain B13 will not take place. The same seems to be true for the transferase of Ralstonia sp. strain PS12 (DSZM8910) (B. Kuhn, unpublished results), an organism growing with 1,2,4-trichloro- and 1,2,4,5-tetrachlorobenzene via 3,4,6-trichlorocatechol and the modified ortho cleavage pathway with 2-chloro-3-oxoadipate as the metabolite (56).

DISCUSSION

We have purified and characterized the 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13, two enzymes which are necessary to finalize the 3-oxoadipate and the modified ortho cleavage pathway and to reach the Krebs cycle. The reactions were analyzed for substrates and products, with special emphasis on the capability to convert a chlorosubstituted substrate which might arise in the degradation of trichlorocatechol.

CoA transferases.

CoA transferases have been identified in many prokaryotes, such as in anaerobic fermenting bacteria and aerobic bacteria, and in the mitochondrial tissues of humans and other mammals. Although CoA transferases are very conserved proteins (9, 45), mechanistically and functionally similar in catalyzing the reversible transfer of one CoA from one carboxylic acid to another, their substrate ranges and their roles in metabolism appear to be very different. (i) Succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid CoA transferase (EC 2.8.3.5) is responsible for the formation of acetoacetyl-CoA by transfer of a CoA moiety from succinyl-CoA to an 3-oxoacid, usually acetoacetate. In higher eukaryotes it is a mitochondrial enzyme which plays a crucial role in ketone body metabolism. This type of transferase has also been found in bacteria. (ii) Bacterial 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase (EC 2.8.3.6) carries out the penultimate step in the conversion of benzoate and 4-hydroxybenzoate to tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates in bacteria utilizing the 3-oxoadipate pathway. (iii) Bacterial acetate-CoA transferase (EC 2.8.3.8) provides the ability to grow on various fatty acids. (iv) Clostridial butyrate-acetoacetate-CoA transferase (EC 2.8.3.9) acts mainly to detoxify the medium by removing the acetate and butyrate excreted earlier in the fermentation. (v) Glutaconate-CoA transferase (EC 2.8.3.12) of the strict anaerobic organism Acidaminococcus fermentans is involved in the degradation of glutamate.

With respect to its function, the B13 enzyme is a 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA-dependent transferase, since acetoacetate and acetyl-CoA fail to be substitutes as acceptor and donor compounds for the CoA moiety.

CoA transferases appear in a variety of subunit compositions. Most bacterial CoA transferases are made of two subunits, whereas the eukaryotic CoA transferases are monomeric enzymes. The subunit compositions of bacterial CoA transferases range from monomer (A) (4) to hetero-octamers ([AB]4) (7). Most CoA transferases are heterodimers with two subunits (A and B) of about 25 kDa. It has been shown that the pig heart succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid CoA transferase consists of a single chain which is colinear with the bacterial A and B chains (45). Bacterial CoA transferases with homodimeric structures similar to that of the pig heart enzyme have been purified from Peptostreptococcus elsdenii (66) and Clostridium aminobutyricum (57). The B13 transferase is a heterotetramer of the type A2B2 with an overall size of 120,000 Da.

Sequence analysis of the N-terminal amino acid sequences of both subunits of the transferase of strain B13 with protein sequences deduced from known CoA transferase genes showed only low identity. Subunit A was 40% identical to subunit A of the glutaconate-CoA transferase of anaerobic fermenting organism Acidaminococcus fermentans (36). Identities to 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferases of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (CatI) and of P. putida (PcaI), which function in the degradation of aromatic compounds, were 32 and 28%, respectively (20, 44). Subunit B was 44% identical to the glutaconate-CoA transferase of Acidaminococcus fermentans but only 16% identical to the transferases of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (CatJ) and P. putida (PcaJ).

Yeh and Ornston (71) have purified the 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferases from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and P. putida and have published short N-terminal amino acid sequences without assignment to the subunits. According to Parales and Harwood (45) the sequences of the transferase of P. putida are the following: subunit A, MINKTY; subunit B, MTITKKL. However, neither the 30-amino-acid sequence of subunit A of B13 transferase nor the 25-amino-acid sequence of subunit B matches the respective N termini of the CoA transferase from P. putida.

Thiolases.

Two different types of thiolases (24, 47, 70) are found both in eukaryotes and in prokaryotes: 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase (also called thiolase I or β-ketothiolase; EC 2.3.1.16) and acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (also called thiolase II) (EC 2.3.1.9). 3-Oxoacyl-CoA thiolase has a broad chain length specificity for its substrates and is involved in degradative pathways such as fatty acid β-oxidation. Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase is specific for the thiolysis of acetoacetyl-CoA and is involved in biosynthetic pathways such as poly-β-hydroxybutyrate synthesis and steroid biogenesis.

With respect to its function the purified B13 thiolase is the only degradative one using a dicarboxylic acid as the substrate.

Depending on the function in metabolism, thiolases appear in a variety of subunit compositions. Thiolase I, catalyzing the last step in the β-oxidation cycle, is part of the multienzyme complex and is composed of two types of subunits: the α-subunit exhibits 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase and 2-enoyl-CoA hydratase activity, while the β-subunit exhibits 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase activity. Some multienzyme complexes have been purified, and their compositions are as follows. A dimer composition has been reported for Candida tropicalis (43,000 Da each) (31), rat peroxisomal enzyme (40,000 Da each) (38), and rat mitochondrial enzyme (41,000 Da each) (38), while tetramers were found for the thiolase of pigs and Alcaligenes eutrophus (46,000 Da each) (23, 64), Pseudomonas fragi (two subunits of 73,000 Da each and two subunits of 42,000 Da each) (25), and E. coli (two subunits of 78,000 Da each and two subunits of 42,000 Da each (46).

In contrast, thiolase II, catalyzing the first step in poly-β-hydroxybutyrate biosynthesis or short-chain fatty acid metabolism, is a homotetramer with subunit sizes ranging from 38,000 to 44,000 Da in E. coli (12), C. acetobutyricum (69), Clostridium kluyveri (63), Zoogloea ramigera (45), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (65), and Alcaligenes eutrophus (47).

Thiolase of strain B13 is a tetramer of the type A4 and, with respect to the composition, a thiolase II.

Sequence analysis of the 17-amino-acid sequence with the translated protein sequence from known 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase genes of P. putida (21), R. opacus (15), and a Streptomyces sp. (26) and acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase genes of E. coli (1) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (72) showed high identities. These data confirm that the B13 enzyme is member of the thiolase II group.

Function in the degradation of substituted 3-oxoadipates.

Since both the 2- and the 4-substituted 3-oxoadipates bear a chiral carbon atom, one can speculate that the recalcitrance of these compounds might be due to the wrong enantiomer being present in the racemic mixture formed in the chemical preparation, which hinders the conversion of the right enantiomer. This argument might be valid for 3-oxoadipates prepared by the chemical method from enelactones. However, when the 3-oxoadipates were formed by the maleylacetate reductase only the right enantiomer should be expected to occur. Therefore the absence of activity cannot be attributed to a wrong enantiomer since there was activity with 4-methyl-3-oxoadipate but there was no indication of any conversion of the respective chloroanalog.

In conclusion, we have shown that 3-oxoadipate is degraded by a 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-CoA transferase and a 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase to reach the tricarboxylic acid cycle. However, the system failed to convert chlorosubstituted compounds expected in the degradation of trichlorocatechols. Therefore, we decided to term the genes encoding these enzymes cat genes instead of chlorocatechol genes (18). Currently, research focuses on the enzyme(s) responsible for the degradation of chlorosubstituted 3-oxoadipates as well as the regiospecificity of the upper enzymes of the modified ortho cleavage pathway to have clear-cut proof of the metabolites formed.

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by a grant from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by the European Union, contract BIO4-CT97-2040.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., T. Baba, K. Hayashi, T. Inada, K. Isono, T. Itoh, H. Kasai, K. Kashimoto, S. Kimura, M. Kitakawa, M. Kitagawa, K. Makino, T. Miki, K. Mizobuchi, H. Mori, T. Mori, K. Motomura, S. Nakade, Y. Nakamura, H. Nashimoto, Y. Nishio, T. Oshima, N. Saito, G. Sampei, T. Y. Seki, S. Sivasundaram, H. Tagami, J. Takeda, K. Takemoto, Y. Takeuchi, C. Wada, Y. Yamamoto, and T. Horiuchi. 1996. A 570-kb DNA sequence of the Escherichia coli K-12 genome corresponding to the 28.0 to 40.1 min region on the linkage map. DNA Res. 3:363–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allred, J. B. 1965. Interference of thiols in acetoacetate determination. Anal. Biochem. 11:138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armengaud, J., K. N. Timmis, and R. M. Wittich. 1999. A functional 4-hydroxysalicylate/hydroxyquinol degradative pathway gene cluster is linked to the initial dibenzo-p-dioxin pathway genes in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J. Bacteriol. 181:3452–3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baetz, A. L., and M. J. Allison. 1990. Purification and characterization of formyl-coenzyme A transferase from Oxalobacter formigenes. J. Bacteriol. 172:3537–3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantititation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunsbach, F. R., and W. Reineke. 1995. Degradation of chloroaromatics in soil slurry by a mixed culture of specialized organisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 43:529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckel, W., U. Dorn, and R. Semmler. 1981. Glutaconate CoA-transferase from Acidaminococcus fermentans. Eur. J. Biochem. 118:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corkey, B. E., M. Brandt, R. J. Williams, and J. R. Williamson. 1981. Assay of short-chain acyl coenzyme A intermediates in tissue extract by high-pressure liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 118:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corthésy-Theulaz, I. E., G. E. Bergonzelli, H. Henry, D. Bachmann, D. D. Schorderet, A. L. Blum, and L. N. Ornston. 1997. Cloning and characterization of Helicobacter pylori succinyl CoA:acetoacetate CoA-transferase, a novel prokaryotic member of the CoA-transferase family. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25659–25667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorn, E., M. Hellwig, W. Reineke, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1974. Isolation and characterization of a 3-chlorobenzoate degrading pseudomonad. Arch. Microbiol. 99:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn, E., and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1978. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on 1,2-dioxygenation of catechol. Biochem. J. 174:85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncombe, G. R., and F. E. Frerman. 1976. Molecular and catalytic properties of the acetoacetyl-coenzyme A thiolase of Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 176:159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elvidge, J. A., R. P. Linstead, B. A. Oekin, P. Sims, H. Baer, and D. B. Pattison. 1950. Unsaturated lactones and related substances. Part IV. Lactonic products derived from muconic acid. J. Chem. Soc. 1950:2228–2235. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erb, R. W., C. A. Eichner, I. Wagner-Döbler, and K. N. Timmis. 1997. Bioprotection of microbial communities from toxic phenol mixtures by a genetically designed pseudomonad. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eulberg, D., S. Lakner, L. A. Golovleva, and M. Schlömann. 1998. Characterization of a protocatechuate catabolic gene cluster from Rhodococcus opacus 1CP: evidence for a merged enzyme with 4-carboxymuconolactone-decarboxylating and 3-oxoadipate enol-lactone-hydrolyzing activity. J. Bacteriol. 180:1072–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frantz, B., K. L. Ngai, D. K. Chatterjee, L. N. Ornston, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1987. Nucleotide sequence and expression of clcD, a plasmid-borne dienelactone hydrolase gene from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J. Bacteriol. 169:704–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freier, R. K. 1974. Wasseranalyse, 2nd ed., p.45–46. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany.

- 18.Göbel, M., K. Kassel-Cati, E. Schmidt, and W. Reineke. 2002. Degradation of aromatics and chloroaromatics by Pseudomonas sp. strain B13: cloning, characterization, and analysis of sequences coding 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA) transferase and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase. J. Bacteriol. 184:216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halden, R. U., S. M. Tepp, B. G. Halden, and D. F. Dwyer. 1999. Degradation of 3-phenoxybenzoic acid in soil by Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes POB310(pPOB) and two modified Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3354–3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartnett, C., E. L. Neidle, K. L. Ngai, and L. N. Ornston. 1990. DNA sequences of genes encoding Acinetobacter calcoaceticus protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: evidence indicating shuffling of genes and of DNA sequences within genes during their evolutionary divergence. J. Bacteriol. 172:956–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harwood, C. S., N. N. Nichols, M. K. Kim, J. L. Ditty, and R. E. Parales. 1994. Identification of the pcaRKF gene cluster from Pseudomonas putida: involvement in chemotaxis, biodegradation, and transport of 4-hydroxybenzoate. J. Bacteriol. 176:6479–6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havel, J., and W. Reineke. 1993. Degradation of Aroclor 1221 in soil by a hybrid pseudomonad. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 108:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haywood, G. H., A. J. Anderson, L. Chu, and E. A. Dawes. 1988. Characterization of two 3-ketothiolases in the polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesizing organism Alcaligenes eutrophus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 52:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igual, J. C., C. Gonzalez-Bosch, J. Dopazo, and J. E. Perez-Ortin. 1992. Phylogenetic analysis of the thiolase family. Implications for the evolutionary origin of peroxisomes. J. Mol. Evol. 35:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imamura, S., S. Ueda, M. Mizugaki, and A. Kawaguchi. 1990. Purification of multienzyme complex for fatty acid oxidation from Pseudomonas fragi and reconstitution of the fatty acid oxidation system. J. Biochem. 107:184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwagami, S., K. Yang, and J. E. Davies. 2000. Characterization of the protocatechuic acid catabolic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. strain 2065. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1499–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasberg, T., V. Seibert, M. Schlömann, and W. Reineke. 1997. Cloning, characterization, and sequence analysis of the clcE gene encoding the maleylacetate reductase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J. Bacteriol. 179:3801–3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaschabek, S. R., and W. Reineke. 1994. Synthesis of bacterial metabolites from haloaromatic degradation. 1. Fe (III)-catalyzed peracetic acid oxidation of halocatechols, a facile entry to cis,cis-2-halo-2,4-hexadienedioic acids and 3-halo-5-oxo-2(5H)-furanylideneacetic acids. J. Org. Chem. 59:4001–4003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaschabek, S. R., and W. Reineke. 1995. Maleylacetate reductase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13: specificity of substrate conversion and halide elimination. J. Bacteriol. 177:320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katagiri, M., and O. Hayaishi. 1957. Enzymatic degradation of β-ketoadipic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 226:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurihara, T., M. Ueda, and A. Tanaka. 1989. Peroxisomal acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase from n-alkane-utilizing yeast Candida tropicalis: purification and characterization. J. Biochem. 106:474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London). 227:680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehrbach, P. R., J. Zeyer, W. Reineke, H.-J. Knackmuss, and K. N. Timmis. 1984. Enzyme recruitment in vitro: use of cloned genes to extend the range of haloaromatics degraded by Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J. Bacteriol. 158:1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leser, T. D., M. Boye, and N. B. Hendriksen. 1995. Survival and activity of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13(FR1) in a marine microcosm determined by quantitative PCR and an rRNA-targeting probe and its effect on the indigenous bacterioplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1201–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lüönd, R. M., J. Walker, and R. W. Neier. 1992. Assessment of the active-site requirements of 5-aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase: evaluation of substrate and product analogues as competitive inhibitors. J. Org. Chem. 18:5005–5013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mack, M., K. Bendrat, O. Zelder, E. Eckel, D. Linder, and W. Buckel. 1994. Location of the two genes encoding glutaconate coenzyme A-transferase at the beginning of the hydroxyglutarate operon in Acidaminococcus fermentans. Eur. J. Biochem. 226:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merril, C. R., D. Goldman, S. A. Sedman, and M. H. Ebert. 1981. Ultrasensitive stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels shows regional variation in cerebrospinal fluid proteins. Science 211:1437–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazawa, S., S. Furuta, T. Osumi, T. Hashimoto, and N. Ui. 1981. Properties of peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase from rat liver. J. Biochem. 90:511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montforts, F.-P., U. M. Schwartz, P. Maib, and G. Mai. 1990. Darstellung 2-methoxysubstituierter Pyrrole durch intramolekulare Aza-Wittig-Reaktionen. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1990:1037–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nüsslein, K., D. Maris, K. N. Timmis, and D. F. Dwyer. 1992. Expression and transfer of engineered catabolic pathways harbored by Pseudomonas spp. introduced into activated sludge microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3380–3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ornston, L. N. 1966. The conversion of catechol and protocatechuate to β-ketoadipate by Pseudomonas putida. II. Enzymes of the protocatechuate pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 241:3787–3794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ornston, L. N. 1966. The conversion of catechol and protocatechuate to β-ketoadipate by Pseudomonas putida. III. Enzymes of the catechol pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 241:3795–3799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ottey, L., and E. L. Tatum. 1957. The cleavage of β-ketoadipic acid by Neurospora crassa. J. Biol. Chem. 229:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer, M. A. J., E. Differding, R. Gamboni, S. F. Williams, O. P. Peoples, C. T. Walsh, A. J. Sinskey, and S. Masamune. 1991. Biosynthetic thiolase from Zoogloea ramigera. Evidence for a mechanism involving Cys-378 as the active site base. J. Biol. Chem. 266:8369–8375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parales, R. E., and C. S. Harwood. 1992. Characterization of the genes encoding β-ketoadipate:succinyl-coenzyme A transferase in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 174:4657–4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pawar, S., and H. Schulz. 1981. The structure of the multienzyme complex of fatty acid oxidation from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 256:3894–3899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peoples, O. P., and A. J. Sinskey. 1989. Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Characterization of the genes encoding β-ketothiolase and acetoacetyl-CoA reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 264:15293–15297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen, D. J., J. W. Cary, J. Vanderleyden, and G. N. Bennett. 1993. Sequence and arrangement of genes encoding enzymes of the acetone-production pathway of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC824. Gene 123:93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powlowski, J. B., and S. Dagley. 1985. β-Ketoadipate pathway in Trichosporon cutaneum modified for methyl-substituted metabolites. J. Bacteriol. 163:1126–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powlowski, J. B., J. Ingebrand, and S. Dagley. 1985. Enzymology of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Trichosporon cutaneum. J. Bacteriol. 163:1136–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravatn, R., R. Studer, D. Springael, A. J. B. Zehnder, and J. R. van der Meer. 1998. Chromosomal integration, tandem amplification, and deamplification in Pseudomonas putida F1 of a 105-kilobase genetic element containing the chlorocatechol degradative genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J. Bacteriol. 180:4360–4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravatn, R., A. J. B. Zehnder, and J. R. van der Meer. 1998. Low-frequency horizontal transfer of an element containing the chlorocatechol degradation genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 to Pseudomonas putida F1 and to indigenous bacteria in laboratory-scale activated-sludge microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2126–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reineke, W., and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1979. Construction of haloaromatics utilising bacteria. Nature (London) 277:385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reineke, W. 1998. Development of hybrid strains for the mineralization of chloroaromatics by patchwork assembly. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:287–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rojo, F., D. H. Pieper, K. H. Engesser, H.-J. Knackmuss, and K. N. Timmis. 1987. Assemblage of ortho cleavage route for simultaneous degradation of chloro- and methylaromatics. Science 238:1395–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sander, P., R.-M. Wittich, P. Fortnagel, H. Wilkes. and W. Francke. 1991. Degradation of 1,2,4-trichloro- and 1,2,4,5-tetrachlorobenzene by Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1430–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scherf, U., and W. Buckel. 1991. Purification and properties of 4-hydroxybutyrate coenzyme A transferase from Clostridium aminobutyricum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2699–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlömann, M., E, Schmidt, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1990. Different types of dienelactone hydrolase in 4-fluorobenzoate-utilizing bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:5112–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt, E., and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1980. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Conversion of chlorinated muconic acids into maleoylacetic acid. Biochem. J. 192:339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt, E., G. Remberg, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1980. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Halogenated muconic acids as intermediates. Biochem. J. 192:331–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Segat-Dioury, F., O. Lingibé, B. Graffe, M.-C. Sacquet, and G. Lhommet. 2000. A general synthesis of enantiopure 1,2-aminoalcohols via chiral morpholinones. Tetrahedron 56:233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simon, E. J., and D. Shemin. 1953. The preparation of S-succinyl coenzyme A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75:2520. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sliwkowski, M. X., and M. G. N. Hartmanis. 1984. Simultaneous single-step purification of thiolase and NADP-dependent 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase fromClostridium kluyveri. Anal. Biochem.141:344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Staack, H., J. F. Binstock, and H. Schulz. 1978. Purification and properties of a pig heart thiolase with broad chain length specificity and comparison of thiolases from pig heart and Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 253:1827–1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suzuki, F., W. L. Zahler, and D. W. Emerich. 1987. Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase of Bradyrhizobium japonicum bacteroids: purification and properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 254:272–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tung, K. K., and W. A. Wood. 1975. Purification, new assay, and properties of coenzyme A transferase from Peptostreptococcus elsdenii. J. Bacteriol. 124:1462–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van der Meer, J. R., R. Ravatn, and V. Sentchilo. 2001. The clc element of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 and other mobile degradative elements employing phage-like integrases. Arch. Microbiol. 175:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vollmer, M. D., U. Schell, V. Seibert, S. Lakner, and M. Schlömann. 1999. Substrate specificities of the chloromuconate cycloisomerases from Pseudomonas sp. B13, Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 and Pseudomonas sp. P51. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiesenborn, D. P., F. B. Rudolph, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 1988. Thiolase from Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 and its role in the synthesis of acids and solvents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2717–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang, S. Y., X. Y. Yang, G. Healy-Louie, H. Schulz, and M. Elzinga. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the fadA gene. Primary structure of 3-ketoacyl-coenzyme A thiolase from Escherichia coli and the structural organization of the fadAB operon. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10424–10429. (Erratum, 266:16255, 1991.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yeh, W.-K., and L. N. Ornston. 1981. Evolutionary homologous α2β2 oligomeric structures in β-ketoadipate succinyl-CoA transferases from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Pseudomonas putida. J. Biol. Chem. 256:1565–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoshioka, S., K. Kato, K. Nakai, H. Okayama, and H. Nojima. 1997. Identification of open reading frames in Schizosaccharomyces pombe cDNAs. DNA Res. 4:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou, J. Z., and J. M. Tiedje. 1995. Gene transfer from a bacterium injected into an aquifer to an indigenous bacterium. Mol. Ecol. 4:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]