Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide from a wbjA mutant, deficient in a putative glycosyltransferase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa serogroup O11, was compared to that from an O-antigen polymerase mutant. Results suggest that WbjA adds the terminal glucose to complete the serogroup O11 O-antigen unit and identifies the biological repeating unit as [-2)-β-D-glucose-(1-3)-α-L-N-acetylfucosamine-(1-3)-β-D-N-acetylfucosamine-(1].

The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, like that of most gram-negative bacteria, is composed of lipid A, an LPS core oligosaccharide, and an O antigen made up of oligosaccharide repeating units extending out from the cell surface. The O antigen is variable, being composed of di- to pentasaccharide heteropolymer repeats, and is immunodominant. On this basis, 20 immunologically distinct P. aeruginosa serogroups have been identified (9). The serogroup O11 O antigen is one of the simplest of these and has the chemical repeating unit structure [-3)-α-L-N-acetylfucosamine-(1-3)-β-D-N-acetylfucosamine-(1-2)-β-D-glucose-(1-]. However, this is not necessarily the biological repeating unit, since the initiating sugar in this O-antigen repeating unit was previously unknown (4).

Synthesis of P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 (3), O5 (2), and O6 (1) O antigens proceeds by the Wzy (O-antigen polymerase)-dependent mechanism typical of heteropolymeric O antigens. According to a current model (5), individual O-antigen repeating units are synthesized on the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane through successive addition of sugar residues to the C55-lipid carrier molecule undecaprenol phosphate (Und-PP). The inner membrane protein Wzx acts as a translocase, moving Und-PP-linked repeating units to the periplasmic face of the inner membrane, where they are polymerized into full-length O antigen by Wzy.

Mutants lacking the O-antigen polymerase are unable to combine individual O-antigen repeating units into full-length O antigen. This results in a distinctive LPS profile on silver-stained polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), consisting of an LPS core band and a single larger band representing LPS core containing a single complete O-antigen unit, a phenotype referred to as core + one. The overall distribution of O-antigen chain lengths is controlled by another membrane protein, Wzz. The O-antigen polymer is transferred to the lipid A-LPS core by the O-antigen ligase, WaaL, a protein encoded outside the cluster containing the genes for O-antigen synthesis.

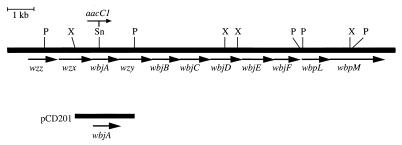

The O-antigen gene locus of the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 strain PA103 has been characterized (3) and consists of 11 open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1), including the wzz, wzx, and wzy genes required for Wzy-dependent O-antigen synthesis. The remaining genes encode predicted proteins, designated WbjA to WbjF, WbpL, and WbpM, which exhibit homology to polysaccharide biosynthetic proteins that presumably function in concert to synthesize individual O-antigen units (3).

FIG. 1.

Organization of the P. aeruginosa O-antigen biosynthetic genes of the serogroup O11 strain PA103, showing the site of insertion of the gentamicin resistance determinant (aacC1) within the wbjA gene. Complementing subclone pCD201, containing an approximately 2-kb XhoI-PstI fragment from pLPS2 (6) in pUCP18 (20), encompassing wbjA, is shown below. Restriction enzyme sites: P, PstI; Sn, SnaBI; and X, XhoI.

WbpL has been strongly implicated as the initiating glycosyltransferase in P. aeruginosa O-antigen synthesis (15). WbjA and WbjE both exhibit significant homology to glycosyltransferases (3). WbjA possesses the conserved regions characteristic of several glycosyltransferase proteins and two conserved aspartate residues within the N-terminal portion of the protein identified as important to β-glycosyltransferase function (18). One of the proteins of this group, ExoM from Sinorhizobium meliloti, has been shown to be a β1-4 glucosyltransferase (10).

In many O-antigen biosynthesis loci, transferase genes are organized in reverse order with respect to the corresponding O-antigen unit, so that the most upstream gene encodes the glycosyltransferase that adds the last sugar to complete the O-antigen unit (14, 19). This suggests that WbjA may transfer the final sugar to complete synthesis of the serogroup O11 O-antigen unit.

To determine the role of wbjA in O-antigen synthesis, a nonpolar insertion in PA103 was constructed. Briefly, an approximately 650-bp ScaI fragment containing part of wbjA was cloned into SmaI-digested pEX100T (22). A gentamicin resistance determinant (aacC1), recovered as a SmaI fragment from plasmid pUCGM (21), was then ligated into the unique SnaBI site within wbjA in the same orientation as wbjA. This plasmid was introduced into PA103 (11) as previously described (3). Gene replacement was confirmed by PCR amplification of chromosomal DNA from PA103 and PA103 wbjA::aacC1 using primers flanking the aacC1 insertion site in wbjA. The PCR product from PA103 wbjA::aacC1 was larger than that generated from wild-type chromosomal DNA by approximately 850 bp, consistent with the size of the aacC1 gene as estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

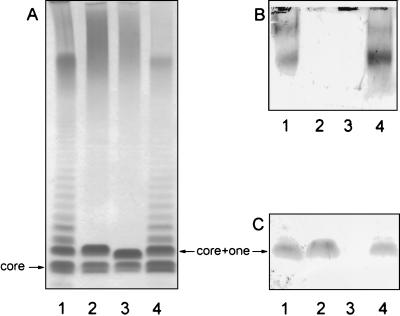

Compared to LPS from the wild-type strain PA103 (Fig. 2A and 2B, lane 1), PA103 wbjA::aacC1 is devoid of full-length O antigen (Fig. 2A and 2B, lane 3), establishing a role for WbjA in serogroup O11 O-antigen synthesis. When plasmid pCD201, containing the entire wbjA gene (Fig. 1), was transferred to PA103 wbjA::aacC1, complementation of the LPS defect was observed (Fig. 2A and 2B, lane 4) confirming that the mutation was nonpolar and that the mutant phenotype resulted solely from the loss of WbjA.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of LPS isolated from P. aeruginosa PA103 and derivatives. LPS, isolated as previously described (3), was separated on 10% NuPAGE bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels (Novex, Los Angeles, Calif.) and visualized by (A) silver staining, (B) Western immunoblot using serogroup O11-specific polyclonal antiserum (13), and (C) Western immunoblot using serogroup O11-specific monoclonal antibody (Rougier Bio-Tech Ltd., Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Lane 1, PA103; lane 2, PA103 wzy::aacC1; lane 3, PA103 wbjA::aacC1; and lane 4, PA103 wbjA::aacC1(pCD201).

Interestingly, although PA103 wbjA::aacC1 lacked full-length O antigen, attached to the LPS core appeared to be a single O-antigen repeating unit. The band for PA103 wbjA::aacC1 (Fig. 2A, lane 3) was observed to migrate slower than the complete core LPS (the lowest band in all the lanes of Fig. 2A) but somewhat faster than the LPS of the PA103 wzy (O-antigen polymerase mutant) (Fig. 2A, lane 2), previously found to contain one complete trisaccharide repeating unit attached to the core (3). The migration rate of the wbjA::aacC1 band thus suggests that it contains an incomplete O-antigen unit, most likely a disaccharide, attached to the core, and this phenotype was therefore designated core + 2/3. The fact that PA103 wbjA::aacC1 was not making any detectable higher-molecular-weight forms of the O antigen (Fig. 2B, lane 3) indicates that truncated O-antigen subunits are not recognized as substrates for O-antigen polymerase.

Further supporting the incomplete nature of the core + 2/3 LPS, a serogroup O11-specific monoclonal antibody which preferentially recognizes forms of LPS containing from one to five O repeating units (3) reacted with the core + one band produced by PA103 wzy::aacC1 (Fig. 2C, lane 2), but failed to react with the core + 2/3 band from PA103 wbjA::aacC1 (Fig. 2C, lane 3). This suggests that the missing sugar residue of the O-antigen is important for recognition by the monoclonal antibody.

Many P. aeruginosa strains produce common antigen or A-band LPS (8). Since most serogroup-specific O-antigen genes, including wbjA, are not distributed among the various serogroup strains, it is unlikely that they would participate in synthesis of the conserved common antigen. As expected, and similar to what was previously observed in PA103 wzy::aacC1 (3), PA103 wbjA::aacC1 produced normal levels of common antigen (data not shown).

The isolation of core + 2/3 LPS from the PA103 wbjA::aacC1 mutant is intriguing in that it indicates that the incomplete O-antigen repeating unit can be recognized and translocated to the periplasm by Wzx. Naide et al. first reported the transfer of unpolymerized O-antigen units to the LPS core in Salmonella (12). Later, it was proposed that O-antigen units must be completed prior to transport (23). However, the isolation of the LPS core substituted with a truncated O-antigen subunit has been reported in Escherichia coli (7) and in Yersinia enterocolitica mutated in the O-antigen glycosyltransferase gene wbcG (25). Feldman et al. (5) also showed stepwise reconstruction of O repeating unit synthesis by addition of subsets of O-antigen genes in a model E. coli strain. This allowed the isolation of an LPS core substituted with as little as a single sugar residue.

The LPS from PA103 wbjA::aacC1 and PA103 wzy::aacC1 was isolated from the water layer after hot phenol-water extraction (16). The purified LPS was hydrolyzed in aqueous 1% acetic acid for 2 h at 100°C. The hydrolysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected. The pellet was washed once with water and centrifuged again. The water wash was added to the supernatant, and the total aqueous phase, containing the oligosaccharides (OSs), was lyophilized. The lyophilized OSs were dissolved in water, applied to a Bio-Gel P-2 column (70 by 1.6 cm), and eluted with water containing 1% 1-butanol. Fractions were assayed for carbohydrate by phenol-sulfuric acid assay. Fractions representing the OS peaks were pooled and lyophilized.

For both mutants, Bio-Gel P2 gel filtration chromatography of the carbohydrates released from the LPS by mild acid hydrolysis resulted in four fractions, I to IV. Fraction IV from both samples did not contain sufficient levels of material for analysis. Each OS fraction was then treated with cold aqueous 48% hydrogen fluoride (HF) and kept for 48 h at 4°C. The HF was removed by flushing under a stream of air, followed by the addition of diethyl ether (600 ml) and drying with a stream of air. This step was repeated three times, and the resulting residue was dissolved in deionized water at 4°C and lyophilized. The resulting OSs were analyzed for their glycosyl components and by mass spectrometry (MS).

The glycosyl composition of each sample was determined by the preparation and combined gas-liquid chromatography-MS analysis of partially methylated alditol acetates and of trimethylsilyl methyl glycosides, as previously described (24). The fraction I samples from both mutants contained only rhamnose (Rha) and glucose (Glc). The various OS fractions from both mutants were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) MS using a Hewlett Packard LD-TOF system. The samples were dissolved in distilled water at a final concentration of 2 μg/μl, and 1 μl was mixed with the dihydroxy benzoic acid in methanol matrix for analysis.

Analysis of fraction I by MALDI-TOF MS showed that it consisted primarily of a size-heterogeneous polysaccharide up to m/z = 2,700. Numerous molecular ions were present between m/z 1,000 and 2,700, all of which differed from the others by 146 mass units, the size of a single Rha residue. Thus, fraction I is largely a rhamnan polysaccharide. These data confirm that both mutants make the common antigen (A-band LPS) and, therefore, that neither WbjA or Wzy is affected in the synthesis of this polysaccharide. The glucose in this fraction may be due to some other type of glucan, since the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum clearly shows that it is not part of the rhamnan (data not shown).

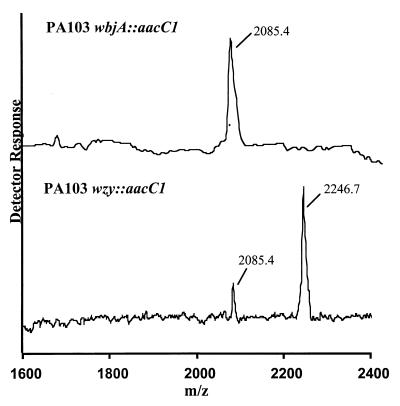

The spectra for both fraction II samples are shown in Fig. 3, and the molecular ions observed for fractions II and III and proposed compositions are given in Table 1. Fractions II and III from both mutants contained Rha, N-acetylfucosamine (FucNAc), Glc, heptose (Hep), and galactosamine (GalN), consistent with the components of the LPS core and the O antigen. Fraction III samples from both samples contained Rha, Glc, Hep, and GalN, corresponding to the LPS core sugars, and only trace levels of FucNAc, which presumably came from slight contamination with fraction II.

FIG. 3.

MALDI-TOF spectra for fraction II from PA103 wbjA::aacC1 (top) and from PA103 wzy::aacC1 (bottom). These spectra were collected in the positive mode.

TABLE 1.

MS data and proposed compositions of the P. aeruginosa OSs in fractions II and III after aqueous HF treatmenta

| Experimental ion | Calculated ion | Proposed composition | Bio-Gel P2 fraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2,246.7 [M + NH4]+ | 2,247.0 | Cb1, Ala1, FucNAc2, Glc5, Rha1, GalN1, Hep2, Kdo1 | II, wzy mutant |

| 2,085.4 [M + NH4]+ | 2,085.0 | Cb1, Ala1, FucNAc2, Glc4, Rha1, GalN1, Hep2, Kdo1 | II, wbjA mutant |

| 1,511.7 [M − H]− | 1,511.4 | Cb1, Ala1, Glc3, Rha1, GalN1, Hep2, Kdoanhydro | III, wzy and wbjA mutants |

| 1,529.0 [M − H]− | 1,529.4 | Cb1, Ala1, Glc3, Rha1, GalN1, Hep2, Kdo | |

| 1,365.0 [M − H]− | 1,365.3 | Cb1, Ala1, Glc3, GalN1, Hep2, Kdoanhydro | III, wzy and wbjA mutants |

| 1,383.0 [M − H]− | 1,383.3 | Cb1, Ala1, Glc3, Rha1, GalN1, Hep2, Kdo |

Cb, carbamoyl; Ala, alanine; FucNAc, N-acetylfucosamine; Glc, glucose; Rha, rhamnose; GalN, galactosamine; Hep, heptose; and Kdo, 3-keto-D-manno-2-octulosonic acid. Fraction II was analyzed in the positive mode, while fraction III was analyzed in the negative mode.

These proposed compositions are consistent with the observed glycosyl components, the masses of the OSs, and reported structures for P. aeruginosa LPSs (4, 17). The MS results show that fraction II from PA103 wzy::aacC1 was larger in mass than fraction II from PA103 wbjA::aacC1 by 162 mass units. This difference corresponds to the mass of one additional hexose residue, and since the only unmodified or simple hexose observed in the sugar component analysis was glucose (see above), this additional hexose must be a Glc residue.

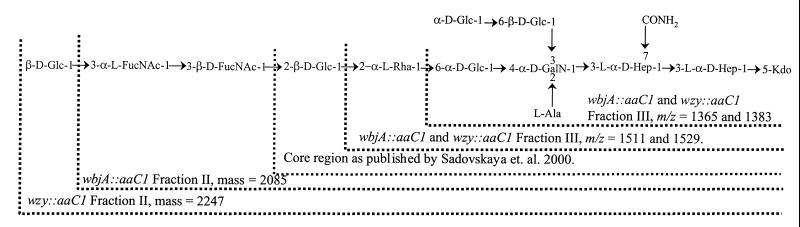

The exact LPS core structure of P. aeruginosa PA103 has not been determined. However, both composition and MS analyses of PA103 wbjA::aacC1 and PA103 wzy::aacC1 are consistent with the recently reported P. aeruginosa serogroup O5 LPS core structure (17). Based on that structure, the proposed structures for the oligosaccharides present on the LPSs from both PA103 wbjA::aacC1 and PA103 wzy::aacC1 are shown in Fig. 4. The structural data for these two mutants supports the conclusion that PA103 wbjA::aacC1 has only a FucNAc-FucNAc disaccharide attached to the lipid A-LPS core region rather than the complete Glc-FucNAc-FucNAc O-antigen unit.

FIG. 4.

Proposed structures for the LPS oligosaccharides from PA103 wbjA::aacC1 and PA103 wzy::aacC1. These structures are based on the P. aeruginosa serogroup O5 LPS core structure recently reported by Sadovskaya et al. (17).

In conclusion, we have identified WbjA as the enzyme responsible for the transfer of glucose to complete the P. aeruginosa serogroup O11 LPS O-antigen subunit, thus defining the biological repeating unit as [-2)-β-D-glucose-(1-3)-α-L-N-acetylfucosamine-(1-3)-β-D-N-acetylfucosamine-(1]. Accordingly, the order of occurrence of wbjA, wbjE, and wbpL within the O-antigen locus (Fig. 1) is the reverse of assembly of the O-antigen unit, consistent with models for O-antigen assembly in other organisms (14, 19).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the NIH (R01 AI35674 and R01 AI37632) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (GOLDBE00P0) to J.B.G. and a grant from the Department of Energy (DE-FG02-93ER20097) to the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center.

We express our gratitude to Jimi Ajijola, Mary Brinig, Jenn Lee, Yan Ren, Betty Shiberu, and Amy Staab for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belanger, M., L. L. Burrows, and J. S. Lam. 1999. Functional analysis of genes responsible for the synthesis of the B-band O-antigen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O6 lipopolysaccharide. Microbiology 145:3505–3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burrows, L. L., D. F. Charter, and J. S. Lam. 1996. Molecular characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O5 (PAO1) B-band lipopolysaccharide gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 22:481–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean, C. R., C. V. Franklund, J. D. Retief, M. J. Coyne, Jr., K. Hatano, D. J. Evans, G. B. Pier, and J. B. Goldberg. 1999. Characterization of the serogroup O11 O-antigen locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA103. J. Bacteriol. 181:4275–4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dmitriev, B. A., Y. A. Knirel, N. A. Kocharova, N. K. Kochetkov, E. S. Stanislavsky, and G. M. Mashilova. 1980. Somatic antigens of Pseudomonas aeruginosa—the structure of the polysaccharide chain of Ps. aeruginosa O-serogroup 7 (Lanyi) lipopolysaccharide. Euro. J. Biochem. 106:643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman, M. F., C. L. Marolda, M. A. Monteiro, M. B. Perry, A. J. Parodi, and M. A. Valvano. 1999. The activity of a putative polyisoprenol-linked sugar translocase (Wzx) involved in Escherichia coli O-antigen assembly is independent of the chemical structure of the O repeat. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35129–35138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg, J. B., K. Hatano, G. Small-Meluleni, and G. B. Pier. 1992. Cloning and surface expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-antigen in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10716–10720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klena, J. D., and C. A. Schnaitman. 1993. Function of the rfb gene cluster and the rfe gene in the synthesis of O antigen by Shigella dysenteriae 1. Mol. Microbiol. 9:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knirel, Y. A. 1990. Polysaccharide antigens of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 17:273–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knirel, Y. A., and N. K. Kochetkov. 1994. The structure of lipopolysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria. III. The structures of O-antigens: a review. Biochemistry (Moscow) 59:1325–1383. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lellouch, A. C., and R. A. Geremia. 1999. Expression and study of recombinant ExoM, a β1–4 glucosyltransferase involved in succinoglycan biosynthesis in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 181:1141–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, P. V. 1973. Exotoxins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. I. Factors that influence the production of exotoxin A. J. Infect. Dis. 128:506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naide, Y., H. Nikaido, P. H. Mäkelä, R. G. Wilkinson, and B. A. D. Stocker. 1965. Semirough strains of Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 53:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pier, G. B., and D. M. Thomas. 1982. Lipopolysaccharide and high molecular weight polysaccharide serotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 148:217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves, P. 1993. Evolution of Salmonella O-antigen variation by interspecific gene transfer on a large scale. Trends Genet. 9:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocchetta, H. L., L. L. Burrows, J. C. Pacan, and J. S. Lam. 1998. Three rhamnosyltransferases responsible for assembly of the A-band D-rhamnan polysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a fourth transferase, WbpL, is required for the initiation of both A-band and B-band lipopolysaccharide synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1103–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan, J. M., and H. E. Conrad. 1974. Structural heterogeneity in the lipopolysaccharide from Salmonella newington. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 162:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadovskaya, I., J.-R. Brisson, P. Thibasult, J. C. Richards, J. S. Lam, and E. Altman. 2000. Structural characterization of the outer core and the O-chain linkage region of lipopolysaccharide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O5. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxena, I. M., R. M. Brown, M. Fevre, R. A. Geremia, and B. Henrissat. 1995. Multidomain architecture of β-glycosyl transferases: implications for mechanism of action. J. Bacteriol. 177:1419–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnaitman, C. A., and J. D. Klena. 1993. Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:655–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schweizer, H. P. 1991. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene 97:109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweizer, H. P. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15:831–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweizer, H. P., and T. T. Hoang. 1995. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 138:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitfield, C. 1995. Biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide O-antigens. Trends Microbiol. 3:178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.York, W. S., A. G. Darvill, M. McNeil, T. T. Stevenson, and P. Albersheim. 1985. Isolation and characterization of plant cell walls and cell wall components. Methods Enzymol. 118:3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, L., J. Radziejewska-Lebrecht, D. Krajewska-Pietrasik, P. Toivanen, and M. Skurnik. 1997. Molecular and chemical characterization of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen and its role in the virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:8. Mol. Microbiol. 23:63–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]