Abstract

Identification and characterization of a suppressor mutation, sup-15, which partially restored secretion in the protein secretion-deficient Bacillus subtilis ecsA26 mutant, led us to discover a novel function of Clp protease. Inactivation of ClpP improved the processing of the precursor of AmyQ α-amylase exposed on the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane. A similar improvement of AmyQ secretion was conferred by inactivation of the ClpX substrate-binding component of the ClpXP complex. In the absence of ClpXP, the transcription of the sipS, sipT, sipV, and lsp signal peptidase genes was elevated two- to fivefold, a likely cause of the improvement of the processing and secretion of AmyQ and complementation of ecs mutations. Specific overproduction of SipT enhanced the secretion. These findings extend the regulatory roles of ClpXP to protein secretion. ClpXP also influenced the processing of the lipoprotein PrsA. A concerted regulation of signal peptidase genes by a ClpXP-dependent activator is suggested. In contrast, Ecs did not affect transcription of the sip genes, pointing to a different mechanism of secretion regulation.

In the niches where they live, bacteria often face changes in osmolarity, acidity, temperature, nutrient availability, and competing microbial populations. To cope with such conditions, stress responses are activated in bacteria, including the enhanced synthesis of molecular chaperones, foldases, extracellular degradative enzymes, and proteases degrading misfolded and abnormal proteins (reviewed in references 9 and 18). In Bacillus subtilis, detrimental conditions can also lead to the development of spores or competence for DNA uptake and recombination (20). The molecular mechanisms responsible for the stress responses and the developmental processes are organized in a complex network of interrelated regulatory circuits.

A major class of proteases, conserved both in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, are ATP-dependent Clp proteases. In bacteria, they are complexes in which the core is composed of a barrel-shaped 14-mer ClpP protein (32), with low intrinsic proteolytic activity (26). In the complex, one or both ends of the ClpP barrel bind a hexameric ATPase (Clp ATPase), providing it with high proteolytic activity and substrate specificity (24). The proteolytic complex plays a key role in degrading misfolded proteins during recovery after various environmental insults and in controlling the quality of translated proteins (reviewed in references 23 and 34). The Clp ATPase components also have the typical properties of molecular chaperones (reviewed in reference 33).

In B. subtilis, three Clp ATPases, ClpC, ClpX, and ClpE, have been identified and are thought to interact with the proteolytic component, ClpP (3, 6, 20, 29). They all are encoded by class III heat shock genes expressed as a response to a wide range of environmental stresses (3, 5, 6, 12). In addition to participating in the overall proteolysis of misfolded proteins, Clp protease complexes play a part in the control of the level of many unstable regulatory proteins (7, 23), thus influencing various biological functions including sporulation and competence development (16, 20, 22, 29). The ClpCP protease also autoregulates its own expression by controlled proteolysis of the global repressor of clp gene expression, CtsR (13).

We have found in B. subtilis an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, designated Ecs, which influences the production of extracellular proteins, competence development, and sporulation (14, 15). Accumulation of precursors of secretory proteins in mutant cells with a defective ATPase subunit, EcsA, or integral membrane component, EcsB, suggested that Ecs is a regulator of protein secretion (15). Furthermore, mutations in ecsA were found to reduce the transcription of exoprotein genes, suggesting that Ecs plays a dual role in controlling, probably in a concerted manner, the expression of secretory proteins as well as their secretion. The protein secretion apparatus in B. subtilis is very similar to that in Escherichia coli (reviewed in reference 17), but there are also clear differences between them. The most obvious one is the presence of several type I signal peptidases (SipS, SipT, SipU, SipV, and SipW) in B. subtilis in contrast to only one (Lep) in E. coli (27, 28).

In the present study we isolated suppressor mutations that restore protein secretion in ecs mutants. One suppressor mutant isolated was found to have an amino acid change in the ClpP protease. We demonstrate that the absence of ClpXP protease increases the expression of signal peptidases, resulting in an increased level of secretion and suppression of the secretion defect of ecs mutants. However, the effects of ClpXP are distinct from the regulation provided by the Ecs transporter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. The bacteria were grown in modified 2×L broth (2×L5; 2% tryptone, 1% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) or BFA minimal medium at 37°C. The BFA medium is a modified Spizizen's minimal salts (SMS) medium (1) containing glutamine instead of ammonium sulfate as the nitrogen source. The growth media contained kanamycin (10 mg liter−1), chloramphenicol 5 (mg liter−1), or erythromycin (1 mg liter−1).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| IH6531 | trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH10) | 11 |

| IH7073 | trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3339) | 15 |

| IH7074 | ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 (pKTH3339) | 15 |

| IH7327 | lsp-lacZ glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7356 | sipS-lacZ glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7357 | sipT-lacZ glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7358 | sipU-lacZ glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7359 | sipV-lacZ glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7360 | sipW-lacZ glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7412 | sipS-lacZ ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7413 | sipT-lacZ ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7414 | sipU-lacZ ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7415 | sipW-lacZ ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7416 | lsp-lacZ ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7441 | trpC2 hisA1 (pKTH3339) | 31 |

| IH7442 | Like IH7074 | This study |

| IH7443 | ecsA26 clpP142 (sup-15) trpC2 hisA1 (pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7668 | ΔclpP::spc trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7683 | ΔclpP::spc trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH10) | This study |

| IH7829 | ΔclpP::spc ecsB::pJH101 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH10) | This study |

| IH7840 | ΔclpP::spc ecsA::pJH101 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH10) | This study |

| IH7841 | Pspac-clpP trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7842 | ecsA26 Pspac-clpP trpC2 hisA1 (pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7857 | clpX::pMUTIN4 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7877 | clpC::pMUTIN4 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7878 | clpX::pMUTIN4 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH10) | This study |

| IH7904 | sipS-lacZ ΔclpP::spc glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7905 | sipT-lacZ ΔclpP::spc glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7906 | sipU-lacZ ΔclpP::spc glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7907 | sipV-lacZ ΔclpP::spc glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7908 | sipW-lacZ ΔclpP::spc glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7909 | lsp-lacZ ΔclpP::spc glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7919 | ecsA::pMUTIN4 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3469) | This study |

| IH7921 | yhcT::pMUTIN2 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3469) | This study |

| IH7930 | clpX::pMUTIN4 trpC2 hisA1 glyB133 (pKTH3469) | This study |

| IH7963 | clpX::pKTH3613 | This study |

| IH7967 | sipS-lacZ clpX::pKTH3613 glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7968 | sipT-lacZ clpX::pKTH3613 glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7969 | sipU-lacZ clpX::pKTH3613 glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7970 | sipV-lacZ clpX::pKTH3613 glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7971 | sipW-lacZ clpX::pKTH3613 glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| IH7993 | glyB133 trpC2 hisA1 (pGDL100, pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7994 | ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 (pGDL100, pKTH3339) | This study |

| IH7995 | ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGDL100 | Kmr, overexpression of sipT | 27 |

| pJH101 | Cmr Apr Tcr, integrable vector | 4 |

| pKTH10 | Kmr, pUB110 derivative with PamyQ-amyQ | 21 |

| pKTH3339 | Cmr, pSX50 derivative with Pxyn-amyQ | 31 |

| pKTH3389 | Emr, pSR11 derivative with Pecs-ecsA | 15 |

| pKTH3469 | Cmr, pSX50 derivative with Pxyn-prsA | M. Vitikainen |

| pKTH3487 | Emr Apr, pMUTIN4 derivative with Pspac-clpP | This study |

| pKTH3517 | Emr, pSR11 derivative with Pecs-ecsA26 | This study |

| pKTH3574 | Emr Apr, pMUTIN4 derivative for clpC knockout | This study |

| pKTH3613 | Emr Apr, pMUTIN4 derivative with inactivated lacZ gene | This study |

| pKTH3623 | Emr Apr, pKTH3613 derivative for clpX knockout | This study |

| pMUTIN4 | Emr Apr, integrable vector | 30 |

MNNG mutagenesis.

Cells of an ecsA26 mutant, IH7442, harboring plasmid pKTH3339 with the Pxyn-amyQ gene, were grown in 2xL5, collected in the mid-exponential growth phase, and resuspended in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 6.5). The suspension was treated with 50 μg of N-methyl-N-nitroso-N"-nitroguanidine (MNNG) for 30 min with shaking. The cells were then harvested, washed twice with the phosphate buffer, and resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer. They were divided into 10 separate cultures of 10 ml each, incubated at 37°C for 4 h with shaking, and then plated onto L-plates containing chloramphenicol, 5% (wt/vol) starch, and 0.2% xylose. After overnight incubation, the mutants were screened for improved secretion of AmyQ, which is indicated by an increased halo size around the raised colonies (11).

Plasmid and strain constructions.

The clpP gene was placed under the transcriptional control of the Pspac promoter in pMUTIN4 (30) as follows. A 313-bp fragment, which contained the ribosome-binding site and the 5" end of the coding region of clpP, was PCR amplified and inserted between the BamHI and HindIII sites of the pMUTIN4 to produce the plasmid pKTH3487. The integration of this plasmid into the chromosome of IH7073 (Table 1) by Campbell-type recombination placed the clpP gene under the control of Pspac. The ecsA26 point mutation was then introduced into the constructed strain by transformation to yield strain IH7842 (ecsA26 Pspac-clpP trpC2 hisA1, pKTH3339). The transformation was carried out by selecting for glyB+ and screening for ecsA26 cotransformants on starch plates by a halo assay (11, 15). The ecsA26 mutation generates an XbaI restriction site; its presence in IH7842 was confirmed. To construct the clpP and clpX knockout mutants (IH7668 and IH7857) containing Pxyn-amyQ, strain IH7073 was transformed with chromosomal DNA of strains QB4916 (trpC2 ΔclpP::spc) and BUG2 (trpC2 lys-3 clpX::pMUTIN4) by selecting transformants resistant to spectinomycin and erythromycin, respectively (6, 20). Strains IH7840 and IH7829 were constructed by cotransforming the ΔclpP::spc deletion and the ecsA::pJH101 or ecsB::pJH101 knockout mutation into IH6531 (Table 1). To construct the clpC knockout mutant (IH7877), a 400-bp internal DNA fragment of the clpC gene was PCR amplified and inserted between the BamHI and HindIII sites of the pMUTIN4. Transformation of IH7073 with the resulting pKTH3574 plasmid and its integration into the chromosome interrupted the clpC gene.

To study the effects of mutational inactivation of the ecsA, clpP, and clpX genes on expression levels of the signal peptidase genes (sipS, sipT, sipU, sipV, sipW, and lsp), the following strains were constructed. The ecsA26 mutation was transformed into strains containing a sip-lacZ fusion gene and the glyB133 marker as described above (Table 1). For an unknown reason, we were unable to construct an ecsA26 mutant strain containing the sipV-lacZ gene. The ΔclpP::spc deletion was introduced into the sip-lacZ strains by transforming with chromosomal DNA of QB4916 and selecting the transformants resistant to spectinomycin (Table 1). A new clpX knockout mutation was constructed by using a derivative of the pMUTIN4, pKTH3613. In this plasmid, the lacZ gene of pMUTIN4 was deleted to avoid its expression from the clpX promoter and consequential interference of measurements of sip-lacZ expression. pKTH3613 was obtained by digesting pMUTIN4 with BamHI and ClaI and then filling in the single-stranded ends of the linearized plasmid with a Klenow fragment, recircularizing the plasmid with DNA ligase, and transforming it into E. coli. An internal 400-bp fragment of the clpX gene was inserted into the HindIII site of pKTH3613 to construct a plasmid, pKTH3623, which, on integration into the clpX locus, interrupted this gene. The ClpX phenotype was verified by microscopy. Cells of IH7963 growing in liquid culture showed elongated and filamentous morphology, a typical phenotype of clpX mutants (6). The strains containing the sip-lacZ fusion genes, with the exception of that containing lsp-lacZ, were transformed with chromosomal DNA from IH7963, and transformants resistant to erythromycin were selected (Table 1). The ecsA26 mutant overproducing the SipT signal peptidase was constructed as follows. A plasmid containing the sipT gene, pGDL100 (27), was first transformed into IH7073 to obtain IH7993 (trpC2 hisA1 glyB133, pKTH3339 pDGL100). The ecsA26 mutation was then transformed into this strain with glyB+ selection as described above to obtain IH7994 (ecsA26 trpC2 hisA1, pKTH3339 pDGL100).

Trypsin accessibility of preAmyQ and AmyQ in protoplasts, immunoblotting, pulse-chase labeling, and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

To study the trypsin accessibility of preAmyQ and AmyQ in protoplasts, the expression of Pxyn-amyQ was induced at the exponential growth phase (100 Klett units) with 0.16 or 0.2% xylose. After 1 h of induction, protoplasts were prepared by lysozyme treatment (31). The protoplasts were incubated with or without trypsin (1 mg ml−1) at 37°C for 30 min. After the incubation, trypsin inhibitor was added (1.2 mg ml−1) and the protoplasts were pelleted by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 5 min). The protoplasts were solubilized in boiling sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer. The amounts of AmyQ and a cytoplasmic protein, GroEL, were analyzed by immunoblotting. Preparation of whole-cell samples and immunoblotting with specific antibodies were performed as previously described (15). Pulse-chase labeling of PrsA was performed at 30°C as described in reference 15, and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was performed as described in reference 6.

Enzymatic assays.

α-Amylase activity was determined using Phadebas amylase test tablets (Pharmacia) as described previously (15). The amylase concentration was calculated from the activity of purified B. amyloliquefaciens α-amylase (Sigma). β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described previously (19) and is expressed as nanomoles per minute per milligram.

RESULTS

Search for suppressor mutations able to restore protein secretion in the ecsA26 mutant.

We used MNNG to mutagenize the ecsA26 mutant (IH7074) and searched for suppressors secreting AmyQ at elevated levels. Strain IH7074 contains plasmid pKTH3339, in which the amyQ gene is under the transcriptional control of the xylose-inducible Pxyn promoter (8). Its induction with 0.2% xylose results in the synthesis of AmyQ at a level that saturates the secretion apparatus (31). Since expression from Pxyn is not regulated by the Ecs system, unlike the amyQ gene's own promoter (15), the method specifically allows the identification of suppressor mutations improving protein secretion and omits mutations affecting the transcription of amyQ.

Screening of 4,000 colonies resulted in 52 putative suppressor mutants. Three of them, sup-6, sup-15, and sup-16, displayed the largest increase of secretion. The presence of the ecsA26 mutation in these suppressor mutants was confirmed by demonstrating the presence of an ecsA26 mutation-specific XbaI restriction site in a PCR fragment amplified from ecsA26 DNA (14).

sup-15 is an extragenic suppressor mutation of ecsA26.

In a backcross experiment, only the sup-15 mutation was found to be unlinked to ecs; a sup-15 recombinant (IH7443) of such a cross was used for further experiments. AmyQ secretion by strain IH7443 was determined and compared with that of the wild type (IH7441) and the ecsA26 parent (IH7442). The Pxyn-amyQ gene (in pKTH3339 in each strain) was induced with 0.02 or 0.2% xylose at the exponential growth phase, and amylase activity in the growth medium was measured.

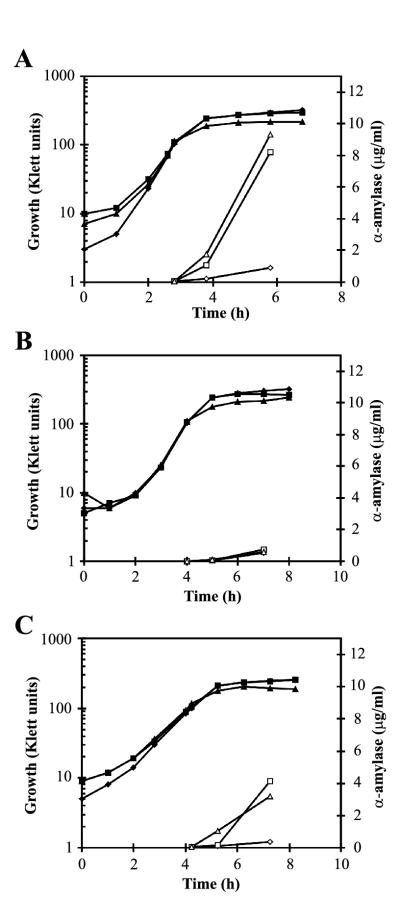

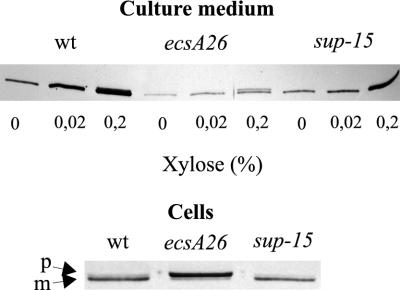

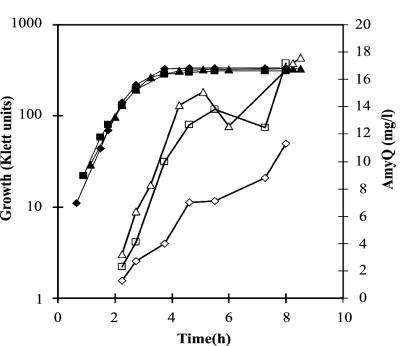

Wild-type cells induced with 0.2% or even 0.02% xylose in this experiment secreted about 10-fold more AmyQ than the basal level measured in the absence of xylose (Fig. 1A). In the ecsA26 mutant, neither concentration of xylose increased the secretion of AmyQ above the low basal level (Fig. 1B). The sup-15 mutation increased AmyQ secretion fivefold over that of the ecsA26 mutant when induced with xylose (Fig. 1C). However, the suppression was partial in the sense that in the wild-type strain the maximal level of secretion was twofold higher (Fig. 1A and C). Immunoblotting showed that the culture medium of the sup-15 mutant contained a significantly larger amount of AmyQ protein than did that of the ecsA26 mutant but a smaller amount than that for the wild type (Fig. 2, upper panel).

FIG. 1.

Secretion of AmyQ α-amylase by the ecsA26 mutant, the sup-15 suppressor mutant, and their wild-type parent. IH7441 (wild type, pKTH3339) (A), IH7442 (ecsA26, pKTH3339) (B), and IH7443 (ecsA26 sup-15, pKTH3339) (C) were grown in modified 2× L-broth up to a cell density of 100 Klett units, after which the expression of Pxyn-amyQ was induced with 0% (◊, ⧫), 0.02% (□, ▪), or 0.2% (▵, ▴) xylose. The concentration of AmyQ (open symbols) in the culture medium was determined enzymatically from samples taken in the late exponential and early stationary growth phases. The solid symbols show growth.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of secreted and cell-associated AmyQ in cultures of the ecsA26 mutant, sup-15 suppressor mutant, and their wild-type parent. The upper panel shows secreted AmyQ in the medium of the cultures in Fig. 1 (the middle time point). The analyzed samples were in 3 μl of culture medium. The lower panel shows cell-associated amylase from cells in which Pxyn-amyQ was induced with 0.02% xylose at a cell density of 100 Klett units for 1 h. The samples are derived from 7.5 μl of the cultures. wt, wild type.

sup-15 facilitates the processing of preAmyQ in the ecsA26 mutant.

Consistent with our previous results (31), wild-type cells contained mature AmyQ but hardly any preAmyQ (Fig. 2, lower panel). In contrast, cells of the ecsA26 mutant almost exclusively contained preAmyQ. Importantly, the amylase pattern of the sup-15 suppressor mutant was similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 2), indicating that sup-15 restores the processing of preAmyQ in ecsA26 mutant. This result was corroborated by determination of the saturation thresholds of the secretion apparatus (Fig. 3). In wild-type cells, preAmyQ began to accumulate at the expression level obtained with 0.08% xylose, whereas in ecsA26 mutant cells, essentially all of the cell-associated amylase was in the precursor form at the 0.02% xylose concentration. The sup-15 mutation shifted the saturation threshold to a higher expression level, similar to that of the wild-type cells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Influence of Ecs, ClpP, ClpC, ClpX, and SipT on the saturation of the secretion apparatus by overproduction of AmyQ. Cells of the strains with the indicated ecsA and clp genotypes were grown in modified 2× L broth, the expression of Pxyn-amyQ was induced at different levels with xylose as indicated at a cell density of 100 Klett units for 1 h, and cell-associated amylase was analyzed by immunoblotting. The saturation of the secretion apparatus is indicated by the accumulation of preAmyQ, when the expression level of Pxyn-amyQ was beyond the saturation threshold of the apparatus as previously described (31). When indicated, the culture was supplemented with 1 mM IPTG. sipT was overexpressed from plasmid pDGL100. The whole-cell samples analyzed correspond to (from left to right) 30, 7.5, 5, 1.3, and 0.6 μl of culture. wt, wild type.

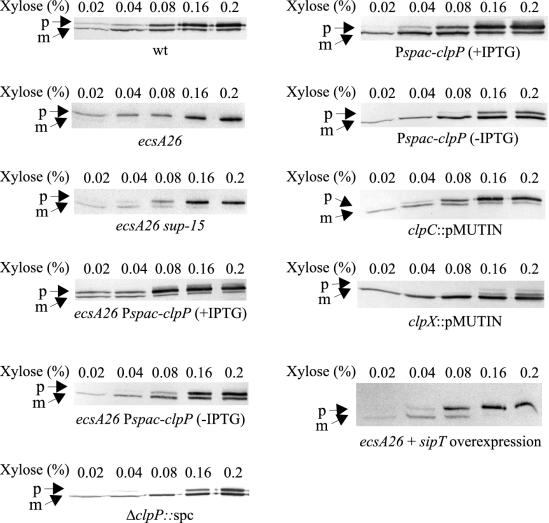

The suppression by sup-15 is caused by a mutation in the ClpP protease.

We analyzed cellular protein patterns of the sup-15, ecsA26, and wild-type strains by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis with the aim of identifying the protein affected by sup-15. The sup-15 mutation was found to cause one striking alteration to the protein pattern of the ecsA26 mutant. The prominent protein spot containing ClpP protease was apparently shifted to a position with a different pI but a similar molecular weight (data not shown). These findings suggest that the ClpP protease of the sup-15 strain contains a mutation that causes abnormal migration in the two-dimensional gel. Consistent with this conclusion, immunoblotting in one-dimensional SDS-PAGE with anti-ClpP antibodies demonstrated that the ClpP protein of the suppressor mutant also migrated slightly faster than did the wild-type ClpP (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

The ClpP protein of the sup-15 suppressor mutant migrates abnormally in SDS-PAGE. Migration of ClpP of the ecsA26 mutant, the sup-15 suppressor mutant, and the wild-type (wt) strain in SDS-PAGE was examined by immunoblotting with anti-ClpP antibodies.

We next sequenced the clpP gene of the sup-15 mutant. The nucleotide sequence revealed a transition of C424 to T, a point mutation that changes the Arg142 to Cys in the “handle” region of a ClpP monomer (32).

Cells of the clpP null mutant are elongated, nonmotile, and unable to grow at high temperature (54°C), and they form filaments (6, 20). The sup-15 mutant was found to have this phenotype, consistent with a clpP mutation. To verify that depletion of ClpP protease activity causes similar improved processing of preAmyQ to that caused by sup-15, we placed the clpP gene under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible Pspac promoter in the chromosome of an ecsA26 mutant and determined the saturation threshold of AmyQ as described above. When Pspac-clpP was expressed, accumulation of the precursor was seen at the lowest synthesis level of AmyQ (0.02% xylose) (Fig. 3). When Pspac-clpP was repressed, the saturation threshold was at a clearly higher synthesis level of AmyQ. Significant precursor accumulation was seen only at xylose concentrations above 0.08%, like in the sup-15 mutant (Fig. 3). The results indicate that the ClpP defect suppresses the secretion deficiency of ecsA26 in the sup-15 suppressor mutant.

We also demonstrated that the absence of ClpP protein suppresses the inactivation of ecsB (ecsB::pJH101) or the whole ecs operon (ecsA::pJH101) (data not shown). Therefore, the suppression was not allele specific.

Depletion of the ClpXP protease complex increases the capacity of the secretion apparatus.

We also examined if the absence of ClpP protease improves protein secretion in the ecs wild-type strain. ΔclpP::spc indeed did increase the level of AmyQ in the culture medium about twofold (Fig. 5). Also, the saturation threshold of the secretion apparatus for AmyQ was shifted above that for the wild type; the saturation and accumulation of preAmyQ occurred at 0.16% xylose in the clpP mutant, in contrast to 0.08% xylose in the wild type (Fig. 3). This was corroborated by a similar result with the inducible Pspac-clpP. The ClpP depletion again shifted the threshold of saturation to the synthesis level of AmyQ obtained with 0.16% xylose (Fig. 3).

FIG. 5.

Effect of mutations of the clpP and clpX genes on the secretion of AmyQ. Cells of IH7683 (ΔclpP::spc, pKTH10) (▵, ▴), IH7878 (clpX::pMUTIN, pKTH10) (□, ▪), and IH6531 (wt, pKTH10) (◊, ⧫) were grown in modified 2× L broth, and culture medium samples were taken for the amylase assay. Open and solid symbols show the concentration of AmyQ and the growth, respectively.

To identify the targeting component that ClpP combines with when affecting protein secretion, we disrupted the clpC and clpX genes and determined the pattern of cell-bound AmyQ proteins at different levels of expression as described above. The pattern and the saturation threshold of the clpC knockout mutant (clpC::pMUTIN; IH7877) were similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 3). In contrast, the clpX mutant (clpX::pMUTIN; IH7857) had a clearly higher capacity to process preAmyQ than did the clpC mutant and it resembled the clpP mutants in this respect (Fig. 3). Furthermore, like the clpP mutant, the clpX mutant secreted AmyQ into the culture medium at about a twofold-higher level than did the wild type (Fig. 5).

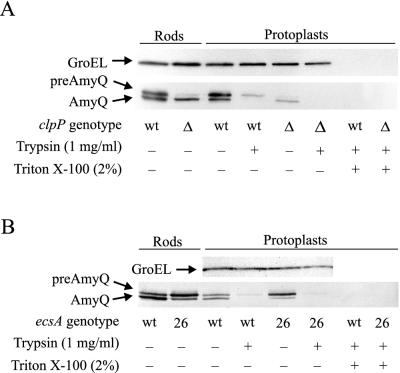

Inactivation of ClpXP influences the processing of preAmyQ and the expression of signal peptidases.

To elucidate the phase of secretion influenced by ClpXP, we determined the accessibility to external trypsin of AmyQ in protoplasts of the ΔclpP::spc (IH7668) and clpX::pMUTIN (IH7857) mutants. In protoplasts of the wild type, most of the preAmyQ was accessible to degradation by trypsin (Fig. 6A), as described previously (31), while GroEL, a cytoplasmic protein, was protected. The small amount of inaccessible preAmyQ and all of the GroEL were degraded by trypsin when the protoplasts were solubilized with Triton X-100, indicating an intracytoplasmic location. Mature AmyQ associated with the protoplasts was completely degraded, indicating that either the whole protein or at least a significant segment of it is surface exposed (Fig. 6A). In the ΔclpP::spc mutant, the sole protoplast-associated form was mature AmyQ in this experiment. As in the wild type, it was completely degraded by external trypsin, suggesting a similar cellular location. A similar result was obtained with the clpX mutant (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Protease accessibility of preAmyQ/AmyQ in protoplasts of the ΔclpP::spc (A) and ecsA26 (B) mutants and the wild-type (wt) strain (A and B). Protoplasts were prepared and treated with trypsin, and the proportion of degraded, surface-exposed preAmyQ/AmyQ was determined by immunoblotting. The amount of cytoplasmic GroEL protein was also determined, to estimate the degree of protoplast lysis. To confirm that all of the preAmyQ/AmyQ in the protoplasts was in a trypsin-sensitive conformation, the trypsin treatment was also carried out in the presence of Triton X-100. The expression of Pxyn-amyQ in the strains shown in the figure was induced with 0.2% (A) and 0.16% (B) xylose.

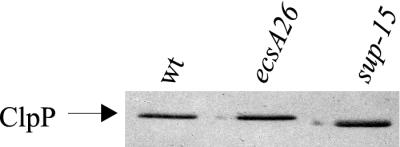

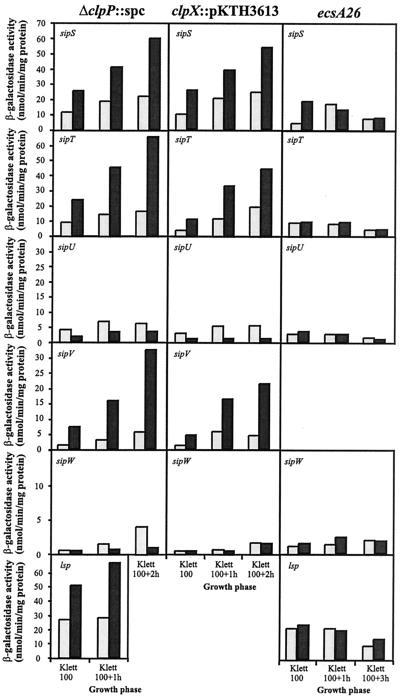

The findings suggest enhanced signal peptide processing in the absence of ClpXP. To find whether ClpXP is involved in the regulation of the transcription of any of the five genes encoding type I signal peptidases (SipS, SipT, SipU, SipV, and SipW), we constructed a set of strains containing the E. coli lacZ gene placed under the control of each sip gene promoter (Psip-lacZ) (28). The ΔclpP::spc or clpX::pKTH3613 mutation was introduced into each strain (Table 1), and the β-galactosidase activities were determined in liquid cultures.

The transcription of sipS and sipT, encoding major signal peptidases, and sipV, encoding a minor signal peptidase, was increased two- to fivefold in both clpP and clpX mutants compared to the wild type (Fig. 7). In contrast, the expression of sipU and sipW, encoding two other minor signal peptidases, was not affected.

FIG. 7.

Expression of signal peptidase genes in the ΔclpP::spc, clpX::pKTH3613, and ecsA26 mutants. Strains containing either a sipS-lacZ, sipT-lacZ, sipU-lacZ, sipV-lacZ, sipW-lacZ, or lsp-lacZ fusion gene in the chromosome were grown in modified 2× L broth, and β-galactosidase activity was determined from samples taken in the exponential growth phase. The activity of sipV-lacZ and lsp-lacZ in the ecsA26 and clpX::pKTH3613 mutants, respectively, was not determined. The dark grey bars indicate the mutants, and the light grey bars indicate the wild type. The measurements were repeated twice.

Overexpression of sipT enhances secretion.

To verify that the increased expression of signal peptidases is indeed responsible for the enhanced capacity of the secretion machinery, we specifically overexpressed sipT, using the ecsA26 mutant (IH7994) expressing amyQ from the Pxyn promoter. As shown in Fig. 3, the ecsA26 mutant cells overexpressing sipT began to accumulate preAmyQ at 0.08% xylose, like the sup-15 suppressor mutant (see above), whereas in ecsA26 with a wild-type level of SipT, saturation of the apparatus took place at a clearly lower inducer level (0.02% xylose). Consistent with the improved processing of preAmyQ, the sipT overexpression increased the secretion of mature AmyQ into the culture medium as detected by immunoblotting (data not shown).

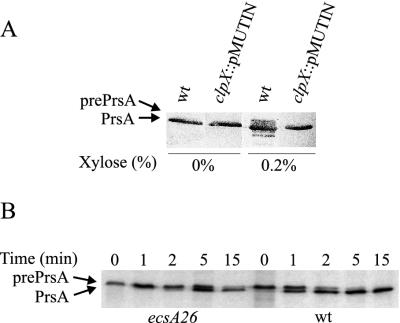

Inactivation of ClpXP also affects the lipoprotein signal peptidase.

As shown in Fig. 7, the clpP::spc mutation also upregulated the transcription of the lsp gene encoding lipoprotein signal peptidase to a degree comparable to that of the sip genes. To demonstrate directly that ClpXP influences prelipoprotein processing, we used an inducible gene construct (Pxyn-prsA), which encodes a lipoprotein, PrsA. At a low level of Pxyn-prsA expression, only the mature PrsA was detected (Fig. 8A). At a higher expression level, the wild-type strain accumulated prePrsA, which migrated in SDS-PAGE as a broad band (or several bands) above the PrsA band (Fig. 8A). The PrsA precursor was not detected in the clpX mutant, pointing to improved prelipoprotein processing, consistent with an increased expression level of lsp in the absence of ClpXP.

FIG. 8.

Processing of prePrsA in cells of the clpX::pMUTIN and ecsA26 mutants and the wild-type (wt) strain. (A) The Pxyn-prsA gene was expressed at the noninduced (0% xylose) or fully induced (0.2% xylose) level. The immunoblot shows the prePrsA and PrsA proteins and their relative amounts. The analyzed whole-cell samples correspond 10 μl (0%) and 4 μl (0.2%) of culture. Since the Pxyn promoter is leaky, the Pxyn-prsA gene is expressed at a fairly high level in the absence of xylose. (B) The effect of ecsA26 on the kinetics of the processing of prePrsA was examined by pulse-chase labeling.

Ecs also affects signal peptide cleavage, but in a manner different from that of ClpXP.

A distinctive feature of ecs mutants is accumulation of unprocessed AmyQ in cells (15). To study the localization of the unprocessed precursor protein, we used trypsin to digest protoplasts of the ecsA26 mutant expressing amyQ at a high level (IH7074) in a similar manner to that shown above for the clpP mutant. Again, preAmyQ was almost completely degraded (Fig. 6B), indicating that the processing of the signal peptide was affected, as was the case for clpP. We also pulse-chase labeled the ecsA26 mutant. In the wild type, about half of the precursor form of PrsA (prePrsA) synthesized during a 1-min pulse was converted to the mature form during the first 1 min of the chase (Fig. 8B). In the ecsA26 mutant, comparable processing required 5 min of chase.

Taken together, the above results indicate that Ecs is involved in the processing of both nonlipoproteins and lipoproteins (15). However, as shown in Fig. 7, the ecsA26 mutation, unlike interruption of clpP or clpX, did not affect the expression of type I signal peptidase genes or lps.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the isolation and characterization of suppressor mutations capable of restoring protein secretion in the secretion deficient ecsA26 mutant resulted in the identification of novel regulators of protein secretion. One suppressor, denoted sup-15, was found to be a mutated clpP gene. ClpP and its cognate Clp ATPases have a role in the regulation of a variety of cellular processes. They mediate adaptive responses to stress conditions (6, 25); temporal regulation of the development of competence for DNA uptake, sporulation, and exoenzyme synthesis (20, 29); cell cycle regulation (10); and control of the replication of bacteriophage DNA (35). In this paper, we show for the first time that ClpXP is also involved in the regulation of protein secretion.

The mutational inactivation or depletion of ClpP protease facilitated a late stage of protein secretion outside the cell membrane, the processing of the signal peptide. This resulted in an increased accumulation of secreted proteins in the culture medium. We could demonstrate that the inactivation of ClpP upregulated the transcription of three type I signal peptidase genes, sipS, sipT, and sipV. SipT is the major signal peptidase which also cleaves the signal peptide of AmyQ (28), the model secretory protein used in this study. The upregulation of sip genes in the absence of ClpP protease is thus in excellent agreement with the enhanced processing of the signal peptides of secretory preproteins and the increased rate of secretion. Taken together, these results suggest that there is a common regulator that, in a concerted manner, controls the transcription of signal peptidase genes. We could demonstrate two elements of specificity. First, only three of the five type I signal peptidases were regulated by Clp protease. Surprisingly, however, the expression of the lipoprotein signal peptidase gene, lsp, was also upregulated by inactivation of clp. Second, the target recognition component of the Clp protease complex responsible for the sip regulation was shown to be the ClpX ATPase; no role for another target recognition component, ClpC, could be demonstrated.

Both clpP and clpX are class III heat shock genes transcribed from ςsgr;A- and/or ςsgr;B-dependent promoters (5). Many Clp protease targets are regulatory proteins, and the activity of this proteolytic system is believed to mediate complex physiological responses to environmental changes (23). The dependence of the transcription of several sip genes on the activity of ClpXP shows that protein secretion belongs to this regulatory system. Furthermore, it is conceivable that the regulator is an activator of sip gene expression. This would be consistent with the major role of ClpXP as a protease, although a chaperone or foldase activity is not excluded. Tjalsma et al. (28) have shown that the transcription of the sipS and sipT genes is temporally regulated by the DegS-DegU two-component system. Nevertheless, sipV was not regulated by this system, suggesting that the predicted Clp-sensitive sip activator is not the DegU response regulator. This conclusion is corroborated by the finding that the expression of sipS is independent of the DegS-DegU regulatory system when cells are grown in TY medium (2), a rich growth medium which is similar to the modified double-strength L broth used in this study.

Our previous studies implicated the Ecs ABC transporter in the regulation of protein secretion by a mechanism related to solute transport and ATPase activity (15). The dominant phenotype of ecs mutants is a decreased rate of protein secretion, deficient processing of signal peptides, and cell-associated accumulation of unprocessed precursors of secretory proteins. In this study we have shown that in the absence of functional Ecs ABC transporter, preAmyQ accumulated on the outer surface of the cell membrane. The finding indicates that Ecs deficiency does not significantly influence protein translocation but arrests it at a later stage of secretion, resulting in the deficient processing. However, this processing defect could not be attributed to altered levels of the signal peptidases as was done for ClpXP. It seems that Ecs controls protein secretion in a manner distinctly different from that of ClpXP. Interestingly, Ecs was also found to regulate the processing of lipoproteins, suggesting that it controls a step in the secretion pathway that is common to both nonlipoproteins and lipoproteins.

The signal peptide of the arrested precursor in ecs mutants is ultimately accessible to signal peptidases, although it is cleaved inefficiently. This was evidenced by the suppression of the deficient processing in the ecsA26 mutant by overexpression of sipT. Our results do not provide a molecular mechanism for the mode of action of Ecs or the consequences of its absence. We speculate that there might be some interaction between the Clp and Ecs regulatory systems. Indeed, we have found that EcsA and EcsA26 proteins are putative substrates for ClpXP protease. Cellular levels of both proteins were higher in clpP and clpX mutants than in the wild type (data not shown). Nevertheless, overexpression of the ecsA26 gene and an increased level of the EcsA26 protein did not alleviate the secretion defect in the ecsA26 mutant with wild-type ClpXP. The Ecs function might also modulate the activity of signal peptidases by influencing the microenvironment at the membrane-wall interface. However, since protoplasts of the ecsA26 mutant were similarly defective in signal peptide processing to the rods of this mutant as determined by pulse-chase labeling (data not shown), this mechanism is unlikely.

It is the identification of the putative sip activator that should lead to a better understanding of the mechanism by which ClpXP-catalyzed proteolysis controls sip expression. Furthermore, the characterization of the Ecs regulon and substrates of the ClpXP protease could lead to the identification of the putative interactions between the two regulatory systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Msadek for the clpP::spc construct and D. Smart for correction of English.

This work was supported by grants from the European Union (Bio4-CT96-0097 and QLK3-CT-1999-00413) and Academy of Finland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos, C., and J. Spizizen. 1961. Requirements for transformation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 81:741-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolhuis, A., A. Sorokin, V. Azevedo, S. D. Ehrlich, P. G. Braun, A. de Jong, G. Venema, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 1996. Bacillus subtilis can modulate its capacity and specificity for protein secretion through temporally controlled expression of the sipS gene for signal peptidase I. Mol. Microbiol. 22:605-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derré, I., G. Rapoport, K. Devine, M. Rose, and T. Msadek. 1999. ClpE, a novel type of HSP100 ATPase, is part of the CtsR heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 32:581-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari, F. A., A. Nguyen, D. Lang, and J. A. Hoch. 1983. Construction and properties of an integrable plasmid for Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 154:1513-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerth, U., A. Wipat, C. R. Harwood, N. Carter, P. T. Emmerson, and M. Hecker. 1996. Sequence and transcriptional analysis of clpX, a class-III heat-shock gene of Bacillus subtilis. Gene 181:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerth, U., E. Krüger, I. Derré, T. Msadek, and M. Hecker. 1998. Stress induction of the Bacillus subtilis clp gene encoding a homologue of the proteolytic component of the Clp protease and the involvement of ClpP and ClpX in stress tolerance. Mol. Microbiol. 28:787-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottesman, S., and M. R. Maurizi. 1992. Regulation by proteolysis: energy-dependent proteases and their targets. Microbiol. Rev. 56:592-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hastrup, S., and M. F. Jacobs. 1990. Lethal phenotype conferred by xylose-induced overproduction of Apr-LacZ fusion protein, p. 33-41. In M. M. Zukowski, A. T. Ganesan, and J. A. Hoch (ed.), Genetics and biotechnology of bacilli. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 9.Hecker, M., W. Schumann, and U. Volker. 1996. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 19:417-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenal, U., and T. Fuchs. 1998. An essential protease involved in bacterial cell-cycle control. EMBO J. 17:5658-5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kontinen, V. P., and M. Sarvas. 1988. Mutants of Bacillus subtilis defective in protein export. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2333-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krüger, E., and M. Hecker. 1998. The first gene of the Bacillus subtilis clpC operon,ctsR, encodes a negative regulator of its own operon and other class III heat shock genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:6681-6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krüger, E., D. Zuhlke, E. Witt, H. Ludwig, and M. Hecker. 2001. Clp-mediated proteolysis in Gram-positive bacteria is autoregulated by the stability of a repressor. EMBO J. 20:852-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leskelä, S., V. P. Kontinen, and M. Sarvas. 1996. Molecular analysis of an operon in Bacillus subtilis encoding a novel ABC transporter with a role in exoprotein production, sporulation and competence. Microbiology 142:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leskelä, S., E. Wahlström, H.-L. Hyyryläinen, M. Jacobs, A. Palva, M. Sarvas, and V. P. Kontinen. 1999. Ecs, an ABC transporter of Bacillus subtilis: dual signal transduction functions affecting expression of secreted proteins, as well as their secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 31:533-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, J., and P. Zuber. 2000. The ClpX protein of Bacillus subtilis indirectly influences RNA polymerase holoenzyme composition and directly stimulates ςsgr;H-dependent transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 37:885-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manting, E. H., and A. J. M. Driessen. 2000. Escherichia coli translocase: the unravelling of a molecular machine. Mol. Microbiol. 37:226-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Missiakas, D., and S. Raina. 1997. Protein misfolding in the cell envelope of Escherichia coli: new signaling pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Msadek, T., F. Kunst, D. Henner, A. Klier, G. Rapoport, and R. Dedonder. 1990. Signal transduction pathway controlling synthesis of a class of degradative enzymes in Bacillus subtilis: expression of the regulatory genes and analysis of mutations in degS and degU. J. Bacteriol. 172:824-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Msadek, T., V. Dartois, F. Kunst, M.-L. Herbaud, F. Denizot, and G. Rapoport. 1998. ClpP of Bacillus subtilis is required for competence development, motility, degradative enzyme synthesis, growth at high temperature and sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:899-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palva, I. 1982. Molecular cloning of α-amylase gene from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and its expression in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 19:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persuh, M., K. Turgay, I. Mandic-Mulec, and D. Dubnau. 1999. The N- and C-terminal domains of MecA recognize different partners in the competence molecular switch. Mol. Microbiol. 33:886-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porankiewicz, J., J. Wang, and A. K. Clarke. 1999. New insights into the ATP-dependent Clp protease: Escherichia coli and beyond. Mol. Microbiol. 32:449-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schirmer, E. C., J. R. Glover, M. A. Singer, and S. Lindquist. 1996. HSP100/Clp proteins: a common mechanism explains diverse functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:289-296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweder, T., K.-H. Lee, O. Lomovskaya, and A. Matin. 1996. Regulation of Escherichia coli starvation sigma factor (ςsgr;S) by ClpXP protease. J. Bacteriol. 178:470-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson, M. W., S. K. Singh, and M. R. Maurizi. 1994. Processive degradation of proteins by the ATP-dependent Clp protease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18209-18215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tjalsma, H., M. A. Noback, S. Bron, G. Venema, K. Yamane, and J. M. van Dijl. 1997.Bacillus subtilis contains four closely related type I signal peptidases with overlapping substrate specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25983-25992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjalsma, H., A. Bolhuis, M. L. van Roosmalen, T. Wiegert, W. Schumann, C. P. Broekhuizen, W. J. Quax, G. Venema, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 1998. Functional analysis of the secretory precursor processing machinery of Bacillus subtilis: identification of a eubacterial homolog of archaeal and eukaryotic signal peptidases. Genes Dev. 12:2381-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turgay, K., J. Hahn, J. Burghoorn, and D. Dubnau. 1998. Competence in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by regulated proteolysis of a transcription factor. EMBO J. 17:6730-6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vagner, V., E. Dervyn, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 144:3097-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitikainen, M., T. Pummi, U. Airaksinen, E. Wahlström, H. Wu, M. Sarvas, and V. P. Kontinen. 2001. Quantitation of the capacity of the secretion apparatus and requirement for PrsA in growth and secretion of α-amylase in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:1881-1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, J., J. A. Hartling, and J. M. Flanagan. 1997. The structure of ClpP at 2.3 Å resolution suggests a model for ATP-dependent proteolysis. Cell 91:447-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wawrzynow, A., B. Banecki, and M. Zylicz. 1996. The Clp ATPases define a novel class of molecular chaperones. Mol. Microbiol. 21:895-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wickner, S., M. R. Maurizi, and S. Gottesman. 1999. Posttranslational quality control: folding, refolding, and degrading proteins. Science 286:1888-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wojtkowiak, D., C. Georgopoulos, and M. Zylicz. 1993. Isolation and characterization of ClpX, a new ATP-dependent specificity component of the Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22609-22617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]