Abstract

Water perception is important for insects, because they are particularly vulnerable to water loss because their body size is small. In Drosophila, gustatory receptor neurons are located at the base of the taste sensilla on the labellum, tarsi, and wing margins. One of the gustatory receptor neurons in typical sensilla is known to respond to water. To reveal the neural mechanisms of water perception in Drosophila, it is necessary to identify water receptor neurons and their projection patterns. We used a Gal4 enhancer trap strain in which GAL4 is expressed in a single gustatory receptor neuron in each sensillum on the labellum. We investigated the function of these neurons by expressing the upstream activating sequence transgenes, shibirets1, tetanus toxin light chain, or diphtheria toxin A chain. Results from the proboscis extension reflex test and electrophysiological recordings indicated that the GAL4-expressing neurons respond to water. We show here that the water receptor neurons project to a specific region in the subesophageal ganglion, thus revealing the water taste sensory map in Drosophila.

Keywords: taste, water receptor neuron

Chemical senses are necessary for all animals to perceive environmental chemical information. In insects, contact chemoreception plays a role in a variety of behaviors, including feeding, courtship, and oviposition site choice. Because sophisticated genetic tools can be used in Drosophila, this organism offers an excellent system to explore the neural and molecular mechanisms of taste (1). The chemosensory organs of Drosophila are composed of bristles called sensilla that are located on the labellum, tarsi, wing margins, and ovipositor. There are usually four gustatory receptor neurons and one mechanosensory neuron at the base of a typical sensillum (2, 3). Electrophysiological studies illustrate that these bipolar receptor neurons respond to different stimuli such as sugar, salt, water, and deterrent compounds (4–6). Although perception of water induces feeding behavior of flies when they are thirsty, there is less information about neural mechanisms of water perception. The axons of gustatory receptor neurons in the labellum project to the subesophageal ganglion (SOG), and those of the tarsi project to the thoracic–abdominal ganglion or to the SOG. Previous studies using horseradish peroxidase (HRP) as a marker reported projection patterns of gustatory receptor neurons on the labellum (7–10) and described seven types of projection patterns. Recently, the Gr family of putative gustatory receptor genes was identified. Understanding the function of this protein group may clarify the neural mechanism underlying the sensory coding of taste (11–13). Grs encode G protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains, such as the sweet and bitter taste receptors found in vertebrates (14–16). One of these Grs, Gr5a, is required for the sensory response of Drosophila to trehalose (17–19). The gene expression pattern of Gr5a was observed by using a Gr5a promoter–Gal4 strain (19–21). Recent studies using Gr promoter–Gal4 strains suggested that gustatory receptor neurons expressing one group of Grs might respond to deterrent compounds (6, 20, 21). Observing the GAL4 expression pattern in the SOG of these Gr-Gal4 strains provided vital information on the taste map that presumably corresponds to stimuli by sugar or deterrent compounds. To reveal a water sensory map in the brain, it is necessary to identify water receptor neurons at a cellular level and to observe their projection patterns.

In this study, we describe a Gal4 enhancer trap line (22, 23) in which GAL4 is expressed in only one of the four gustatory receptor neurons that are housed in taste sensilla on the labellum. Using the GAL4/upstream activating sequence (UAS) system, we expressed several genes that interfere with the function of the GAL4-expressing gustatory receptor neurons. Behavioral and electrophysiological data demonstrate that these neurons respond to water. Observation of the projection patterns of a single GAL4-expressing neuron in the SOG demonstrated that water receptor neurons project to a specific region of the SOG.

Results and Discussion

Electrophysiological studies showed that there are water-responding gustatory receptor neurons in the taste organs of flies (4, 24). It is believed that the receptor neurons might be detecting the change in osmolarity, although the molecular mechanism of water perception is not known. The cellular identification of water receptor neurons might help to elucidate the molecular mechanism of water reception and the neural mechanism of information processing of water perception.

Taste information is received by gustatory receptor neurons and is then transmitted to the brain. Axons of gustatory receptor neurons project to the SOG of the brain. To elucidate the neural mechanism underlying taste discrimination in Drosophila, the projection of four types of gustatory receptor neurons must be determined. To this end we screened the Gal4 enhancer trap strains using UAS-GFP to find strains in which GAL4 is expressed in gustatory receptor neurons in the labellum.

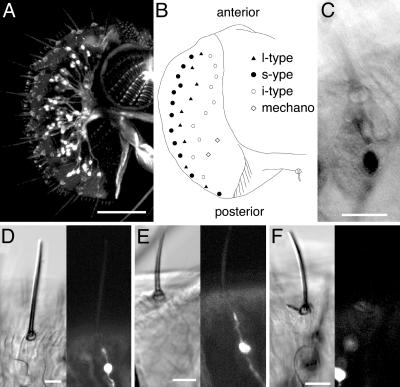

In one of the strains, NP1017, GFP-expressing neurons were observed mainly on the labellum and tarsi (Fig. 1). GFP-expressing neurons were also found in interpseudotracheal papillae on the inside of the labellum. There are 31 taste sensilla on each side of the labellum that are classified into three types: s-, l-, and i-type (5, 25). s- and l-type sensilla have four gustatory receptor neurons and one mechanoreceptor neuron, whereas i-type sensilla have only two gustatory receptor neurons and one mechanoreceptor neuron (5, 25). We found that a single GFP-positive neuron is innervated to all of the l- and s-type sensilla, whereas no GFP-positive neuron was found innervated to the i-type sensilla (Fig. 1 B and D–F). Hiroi et al. (24) found that one of the gustatory receptor neurons in s- and l-type sensilla responds to water and that no neurons respond to water in i-type sensilla. Because there was no GAL4-expressing neuron at the base of all of the i-type sensilla, these results suggest that GAL4-expressing neurons in the labellum in NP1017 may be the water receptor neurons. Immunostaining by using anti-GFP antibody confirmed that only one neuron in the neuronal cluster expressed GFP (Fig. 1C). On tarsi and wing margins, GFP was also expressed in a single neuron in some sensilla, including the m5b sensilla (6), and there were two GFP-positive neurons in other sensilla on tarsi. There were one or two GAL4-expressing neurons at the base of all taste sensilla on wing margins. GFP was expressed at lower levels in other sensory organs such as the eyes, antennae, maxillary palpi, chordotonal organs, and campaniform sensilla. Weak GFP expression, however, was global in these organs and was not restricted to particular cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

GAL4 is expressed in a single gustatory receptor neuron. (A) A fluorescent image of NP1017 carrying the UAS-GFP transgene. The GFP expression pattern on the labellum is shown. (B) Diagram showing distribution of taste sensilla on labellum. Location of l- and s-type sensilla associated with GFP-expressing neurons on the labellum is shown. No GFP-expressing neurons were seen in the i-type sensilla. (C) Immunostaining of GFP-expressing cells on the labellum. Only one neuron was stained with antibody against GFP in each sensillum. (D–F) There are GFP-expressing neurons at the base of l-type (D) and s-type (E) sensilla, but no GFP-expressing neuron was observed in i-type (F) sensilla. (Scale bars: 50 μm in A and 10 μm in C–F.)

The GAL4 expression patterns in the Gal4 enhancer trap strains can mimic the expression of flanking genes near the P [Gal4] insertion site. In NP1017, the P [Gal4] is inserted in the X chromosome, and there are two genes within 20 kb from the insertion point. One gene is CG12497, which encodes a low-density lipoprotein receptor domain-containing protein of unknown function. The other gene, trol (CG7981), encodes a heparin sulfate proteoglycan with a role in normal neuroblast cell division (26, 27). We confirmed by RT-PCR that these two genes are expressed in the tarsi of poxn (28), with no gustatory receptor neurons in the taste sensilla (data not shown). Thus, the GAL4 expression pattern observed in NP1017 might not be related to that of these two genes, although we cannot exclude the possibility that these genes are involved in the development of gustatory receptor neurons.

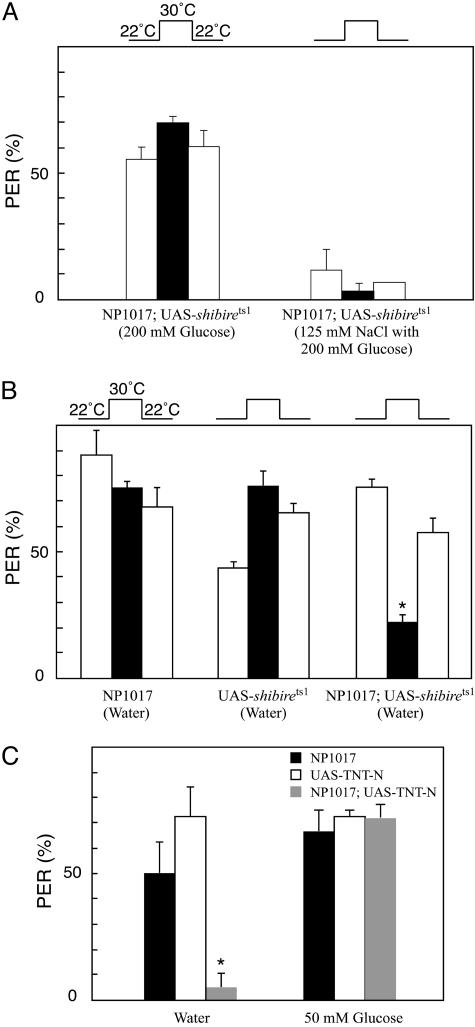

Functional Identification of GAL4-Expressing Neurons in NP1017. Each gustatory receptor neuron in a sensillum responds to sugar, salt, water, or deterrent compounds. GAL4 is expressed in one of the receptor neurons in the labellum of NP1017. To identify the GAL4-expressing cells in the NP1017 strain, we used the GAL4/UAS system. The shibire gene in Drosophila encodes dynamin, which is essential for synaptic vesicle endocytosis. The temperature-sensitive allele shibirets1 suppresses synaptic vesicle recycling at restrictive temperatures (>29°C) and thus blocks synaptic transmission (29). We crossed the NP1017 flies to UAS-shibirets1 flies and examined their behavioral responses to sugar, salt, and water by using the proboscis extension reflex (PER) test. To examine their responses to high concentrations of salt, we touched one prothoracic leg with a sugar solution and the other simultaneously with a NaCl solution, which allowed us to test whether high concentrations of salt inhibit the reflex. Water-deprived flies were used to examine the response to water. We found that responses to sugar and high concentrations of salt were not affected by the action of UAS-shibirets1 at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the proportion of flies that responded to water decreased at the restrictive temperature. The depression of the water response was reversible, and flies recovered their reflex responses shortly after the temperature was lowered (Fig. 2B). Although water responses of taste sensilla on tarsi recovered at 22°C, the percentages of the responding flies were lower than that of the first test at 22°C. There may be some aftereffects induced by the high-temperature treatment, or the action of shibirets1 may not be fully recovered.

Fig. 2.

Functional identification of the GAL4-expressing neuron. (A) Sugar responses (on the left) and salt aversion (on the right) in NP1017 carrying UAS-shibirets1 flies. Open bars represent the percentage of responding flies at a permissive temperature (22°C), and solid bars represent the result at a restrictive temperature (30°C). (B) The percentage of water-responding flies was decreased in NP1017 carrying UAS-shibirets1 flies. Water responses of parental control strains were not affected. (C) Water and sugar responses of taste sensilla on the labellum in NP1017 carrying UAS-TNT flies. Data are based on two to six experiments using 10–16 flies in one series of tests. Error bars indicate SE. *, P < 0.01.

In NP1017, there is one GAL4-expressing neuron in each taste sensillum on the labellum and one or two GAL4-expressing neurons in each sensillum on the tarsi. The results of the PER tests by stimulating a prothoracic leg suggest that at least one of the GAL4-expressing neurons in each taste sensillum on the tarsi responds to water. To identify the function of the GAL4-expressing neuron in the labellum, we examined the PER tests by stimulating the taste sensilla on the labellum. The UAS–tetanus toxin light chain (TNT) strains (30) were used to suppress synaptic transmissions by the GAL4-expressing neurons. TNT encodes a neurotoxin that inhibits synaptic release. We used several independent UAS-TNT lines and examined the water response in the NP1017 carrying UAS-TNT flies using the PER test. We found that the water responses were severely affected (<20% of them responded), whereas the control flies, NP1017, UAS-TNT-N (Fig. 2C), and NP1017 carrying UAS-IMPTNT flies (data not shown), had no effect on the response. Sugar responses of NP1017 carrying UAS-TNT flies were not affected by expression of TNT in GAL4-expressing neurons (Fig. 2C).

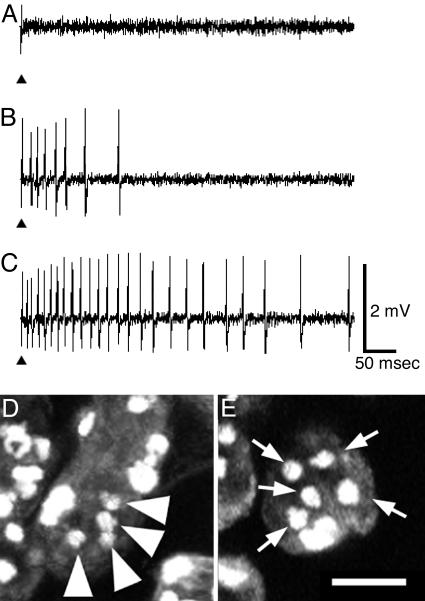

We then used diphtheria toxin A chain (DTI) (31–33) to induce cell death in the GAL4-expressing neurons. When we crossed NP1017 to UAS-DTI flies, all of the offspring died until the pupal stage. Therefore, to express DTI in a few GAL4-expressing gustatory neurons, we used the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker system (34). We first examined the nerve response of l-type sensilla to water among flies in which DTI is thought to be expressed in a limited number of cells. We found an exceptional sensillum that gave poor or no response to water from eight flies (Fig. 3). Several spikes to water were observed only at the start of stimulation in six of eight cases. These same sensilla, however, gave normal responses to sugar and salt (data not shown). We then examined the morphology of the gustatory receptor neurons by staining with propidium iodide for the identified sensilla with lowered responses to water. An l-type taste sensillum contains five neurons (four chemosensory and one mechanosensory cells) and three accessory cells. We found only four neurons associated with the identified sensilla that gave no response to water (arrowheads in Fig. 3D). Diphtheria toxin arrests protein synthesis and thus expression of DTI in water receptor neuron induced malfunction of water responses or induced cell death. These electrophysiological and nuclear staining data indicated that GAL4 is expressed in the water receptor neuron.

Fig. 3.

Electrical and cytological identification of a water receptor neuron by ablation with UAS-DTI. (A) No spikes to water were recorded. (B) In a sensillum of other flies, spikes were recorded only at the initial phase after stimulation. (C) Normal water responses were recorded from most of taste sensilla. Arrowheads show the start of stimulation in A–C. (D and E) There are five neurons (arrows in E) in a taste sensillum, and there are four neurons (arrowheads in D) in an l4 sensillum from which no water responses were recorded, as shown in A. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

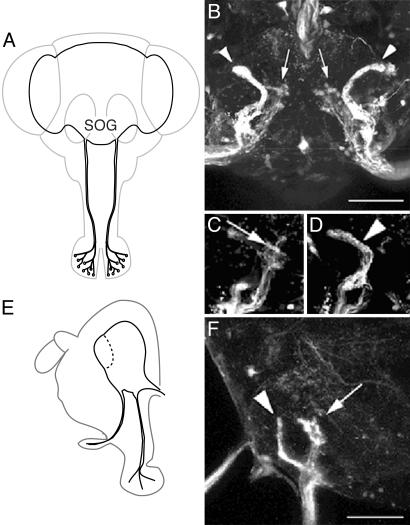

Projection Pattern of Water Receptor Neurons in the SOG. To identify the projection pattern of water receptor neurons, we observed GFP expression patterns in the SOG of NP1017 carrying UAS-GFP flies. The GFP-expressing neurons in the labellum project to two specific regions in the SOG. One group of neurons projects to the lateral–anterior region of the SOG (Fig. 4 B, D, and F, arrowheads), and the other group propels to the central region (Fig. 4 B, C, and F, arrows). The lateral–anterior projection is tortuous and revealed less arborization (Fig. 4 B, D, and F, arrowheads), whereas the central projection showed sparse arborizations in its synaptic region (Fig. 4 B, C, and F, arrow). In the labellum, GAL4 is expressed in receptor neurons of both taste sensilla and interpseudotracheal papillae. To know the projection pattern originated from the water receptor neurons in the taste sensilla, we used the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker system and observed a projection from a single GAL4-expressing neuron (Fig. 5). We studies 24 flies in which GFP was expressed in a single GAL4-expressing neuron in a taste sensillum on the labellum. In half of them a GFP-expressing neuron was connected with an s-type sensillum; in the remaining half, a GFP-expressing neuron was connected with an l-type sensillum. The axon of a GFP-expressing neuron in a taste sensillum projected to the central region in the SOG. In >10 flies, GFP was expressed in interpseudotracheal papillae and the axons of the GFP-expressing neurons projected to the lateral–anterior region in the SOG. Our results show that all of the water receptor neurons in the taste sensilla project to the central SOG region and that the lateral–anterior projection pattern originates from the GAL4-expressing neurons in the interpseudotracheal papillae. All of the water receptor neurons in the s-type sensilla project to the central SOG region and exhibited arborization in the synaptic region (Fig. 5C). In some cases, the axons associated with the water receptor neurons in the l-type sensilla were diverged in the SOG (data not shown). In summary, water receptor neurons in s- and l-type sensilla projected to a same region in the SOG (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 4.

Central projection of the water receptor neurons. (A and E) Diagrams of the frontal (A) and sagittal (E) views of the head and brain. Axons of gustatory receptor neurons in taste sensilla on the labellum project to the SOG. (B) A frontal view of the SOG of an adult brain in NP1017 carrying UAS-GFP flies. Two projection patterns were observed in the SOG (arrows and arrowheads). (C and D) One group of axons is winding and has less arborization (arrowheads in B and D), and another had narrow arborizations in the synaptic region (arrows in B and C). (F) A sagittal view of the projection pattern of water receptor neurons in the SOG. Less-arborized fibers (arrowhead) projected to the anterior region of the SOG, and narrow arborized axons (arrow) projected to the central region of the SOG. Left is anterior. (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

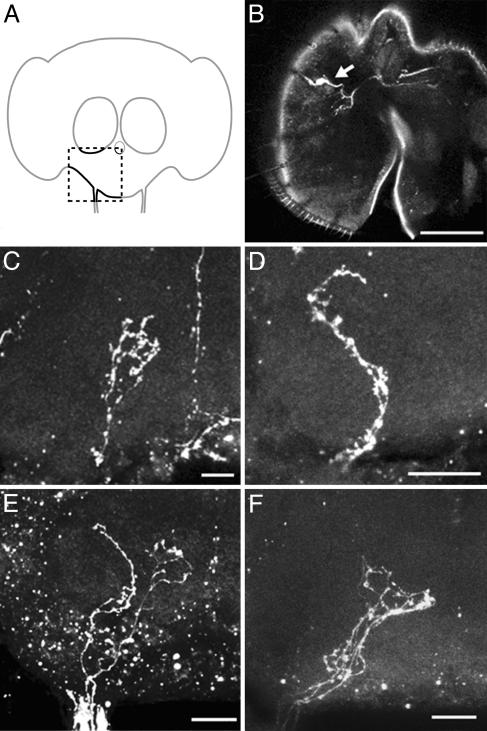

Fig. 5.

Projection pattern of a single GAL4-expressing neuron. Images of projection pattern (shown in C–F) were taken from one side of SOG (a box of broken lines in A). (B and C) There is one GFP-expressing neuron in one side of the labellum. This GFP-expressing neuron is connected with an s-type sensillum (arrow in B), and the axon of this neuron projects to the central region and has arborizations in the synaptic region (C). (D) A GFP-expressing neuron connecting with interpseudotracheal papillae projects to the lateral–anterior region in the SOG. (E) Axons of two GAL4-expressing neurons, one connected with a taste sensillum and the other connected with interpseudotracheal papillae, project to different regions in the SOG. (F) Axons of GAL4-expressing neurons in one s-type sensillum and two l-type sensilla project to same region in the SOG. (Scale bars: 50 μm in B and 20 μm in C–F.)

Previous studies using cobalt filling or HRP uptake on the labellum taste sensilla suggested that there are seven types of projection patterns in the SOG (8, 10). Shanbhag and Singh (10) used HRP combined with water, sugar, or salt to identify the projection patterns of each receptor neuron. Although different projection patterns were observed by HRP uptake in combination with the different compounds, it is uncertain whether the gustatory receptor neurons that absorbed the HRP/compound mixture responded to any of the three compounds. In recent studies using the Gr promoter–Gal4 strain (20, 21), the GAL4 expression patterns observed among several Gr-Gal4 strains (such as Gr32a-Gal4, G47a-Gal4, and Gr66a-Gal4) revealed that seven Gr genes are coexpressed in one of four gustatory receptor neurons. Results from their behavioral tests suggested that the Gr5a-expressing neurons respond to sugar and that the Gr66a-expressing neurons may respond to deterrent compounds (20, 21). The axons of the Gr5a- and Gr66a-expressing neurons project to different specific regions in the SOG (20). In the Gr32a-Gal4, Gr47a-Gal4, and Gr66a-Gal4 strains, the axons of the GAL4-expressing neurons in the each side of the labellum project to the medial SOG, and water receptor neurons in one side of the labellum did not send axons to the medial SOG (Figs. 4B and 5C). We crossed NP1017 carrying UAS-DsRed flies to Gr47a-GFP flies and observed the projection pattern in the SOG (Fig. 6 A–C, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The projection region of the water receptor neurons differs from that of the Gr47a-expressing neurons. We could not confirm whether the projection region of the water receptor neurons and that of the Gr5a-expressing neurons were distinct. GAL4 is expressed in two or three receptor neurons in some of the taste sensilla on the labellum in the Gr5a-Gal4 strain (20, 21). It is not known whether all of the Gr5a-expressing neurons respond to sugar. A part of the projection region comprising the water receptor neurons may overlap with that of the Gr5a-expressing neurons (Fig. 6D). Perception of water, sugar, and low concentrations of salt induces feeding, whereas perception of high concentrations of salt and deterrent compounds inhibits feeding. Our studies support the view that phagostimulatory and adversive information are diverged in the SOG (20, 21). Our studies also revealed that the projections from interpseudotracheal papillae terminate in a region different from those from labellar chemosensilla. Probably the sensory input from the interpseudotracheal papillae is involved in the control of sucking behavior, whereas the input from outer chemosensilla has a role in the initiation of feeding; thus, they are connecting to separate pathways. The taste map of Drosophila provides a simple model system to understand the neural mechanisms underlying feeding behavior.

Materials and Methods

Flies. Flies were reared on cornmeal–glucose–yeast medium at 25°C. The Gr47a-GFP strain was a gift from K. Scott (University of California, Berkeley). The UAS-DTI strain was a gift from R. L. Davis (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston). The UAS-DsRed.S197Y strain was a gift from K. Ito (University of Tokyo, Tokyo). T. Kitamoto (University of Iowa, Iowa City) provided the UAS-shibirets1 strain. UAS-TNT strains and UAS-IMPTNT (inactive TNT) strains were gifts from C. O'Kane (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, U.K.). The UAS-GFP.S65T, FRT-UAS-mCD8::GFP, FRT-Gal80, and hs-FLP strains were from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington). The NP Consortium in Japan has established a large collection of Gal4 enhancer trap strains (23). We crossed NP Gal4 strains to a UAS-GFP strain and checked the GFP expression patterning on the labellum and tarsi under a dissecting microscope equipped with epifluorescence. We identified a number of Gal4 lines in which GFP expression was observed in gustatory receptor neurons. Herein we describe one of these lines, NP1017, in which a P [Gal4] transposon is inserted in the X chromosome.

Imaging. Dissected whole-mount labella, tarsi, brains, and thoracic–abdominal ganglions were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 3 h. The tissues were washed in PBS and mounted in 60% glycerol. GFP images were captured by using an LSM510 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Immunostaining. Whole-mount labella were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 3 h at room temperature. They were washed in PBS-T (PBS containing 5% Triton X-100) and treated in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min at room temperature to kill endogenous peroxidase activity. Immunostaining was carried out by using standard techniques. A rabbit primary anti-GFP antibody (1:250, Sigma) and a HRP-labeled secondary antibody from Envision+ (DAKO) were used. HRP activity was visualized in the presence of 1 mg/ml diaminobenzidine in 0.01% H2O2.

PER Test. The PER test was performed as described by Kimura et al. (35). Briefly, we starved flies for 14 h and allowed them free access to water at 22°C. We then fixed each fly with myristyl alcohol on a glass slide. To test their responses to sugars and salts, we incubated the fixed flies for 2 h in a moist chamber. The flies were satiated with water until they stop responding to it. To measure the sugar responses, we used a 200 mM glucose solution as a stimulus. To measure salt responses, one prothoracic leg was stimulated with a 200 mM glucose solution, and the other leg was stimulated with a 125 mM NaCl solution simultaneously. The PER test was initially performed at 22°C. Next, the flies were placed for 20 min in a moist chamber on a temperature-controlled warming plate set at 30°C. We carried out the second PER test at this temperature, and then flies were reintroduced to the 22°C environment for 20 min before being tested for the third time. To test the water responses, fixed flies were placed in a dry chamber over silica gel for 2 h. Water responses were then tested in a dry silica gel free chamber with water as a stimulus. NP1017 carrying UAS-shibirets1 flies were used to test sugar, salt, and water responses by stimulating the prothoracic leg of each subject. After carrying out the first test at 22°C, the test flies were placed on the warming plate at the 30°C and incubated for 10 min before the second test. The third test at 22°C was performed 10 min after incubation at 22°C. To test the NP1017 carrying UAS-TNT flies, we examined PER to water or sugar by directly stimulating the labellum sensillum.

Electrophysiology. Files were electrically grounded by using a glass capillary tube filled with Drosophila Ringer's solution inserted into the abdomen. The recording and stimulating electrode (glass capillary with tip diameter of 20 μm) was connected to a TasteProbe amplifier (SYNTECH, Hilversum, The Netherlands). Electric signals were amplified and filtered (CyberAmp 320, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA; gain, 1,000; eighth order Bessel pass-band filter, 1–2,800 Hz). Contacting a taste sensillum with the stimulus electrode triggered a data acquisition sequence (sampling rate, 10 kHz, 12 bits; DT2821 Data Translation), which was stored as an individual file on a computer. Data were then analyzed with awave software (36). Spikes were detected and analyzed by using interactive procedures from a custom-made software package, dbwave.

To express DTI (31–33) in a limited number of GAL4-expressing neurons in the labellum of NP1017, we used the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker system (34). To induce mitotic recombination, pupae at 6 h after puparium formation were heat-shocked at 37°C for 30 min. We used a strain with the following genotypes: NP1017; FRT-UAS-mCD8::GFP/FRT-tubP-Gal80; UAS-DTI/hs-FLP. We recorded the electrophysiological responses to sugar, salt, and water on an l-type sensillum that was confirmed to have only one GAL4-expressing neuron on the labellum in NP1017. Solutions of 1 mM KCl, 100 mM sucrose, and 200 mM NaCl were used to stimulate the water-, sugar-, and salt-responding neurons, respectively. Two kinds of spikes with different amplitude, originating from an L1 and an L2 cell, are recorded by the stimulation with 200 mM NaCl.

Nuclear Staining. To observe the number of neurons in each taste sensillum, we performed nuclear staining with propidium iodide (Sigma). Whole-mount labella were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 3 h at room temperature. They were washed in PBS-T and treated in propidium iodide (1 μg/μl) in PBS-T after RNase (10 μg/μl, Roche Diagnostics) treatment for 30 min.

Single-Neuron Labeling. To label a single GAL4-expressing neuron, we used the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker system (34). To induce mitotic recombination, pupae at 6 h after puparium formation were heat-shocked at 37°C for 30 min. Flies with the following genotype were used; NP1017; FRT-UAS-mCD8::GFP/FRT-tubP-Gal80; hs-FLP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center (Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto), R. L. Davis, K. Ito, T. Kitamoto, C. O'Kane, and K. Scott for fly strains. We also thank members of the NP Consortium in Japan for their collaboration, especially K. Ito and N. Tanaka for useful information. We acknowledge F. Yokohari (Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan) for use of the confocal microscope. We are grateful to members of T.T. laboratory, N. Meunier, and F. Marion-Poll for helpful suggestions and discussions and Y. Mitsuiki, T. Takenoshita, and M. Haruta for technical support. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (to T.T.).

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: DTI, diphtheria toxin A chain; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; SOG, subesophageal ganglion; TNT, tetanus toxin light chain; UAS, upstream activating sequence; PER, proboscis extension reflex.

References

- 1.Ishimoto, H. & Tanimura, T. (2004) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falk, R., Bleiseravivi, N. & Atidia, J. (1976) J. Morphol. 150, 327–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stocker, R. F. & Schorderet, M. (1981) Cell Tissue Res. 216, 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujishiro, N., Kijima, H. & Morita, H. (1984) J. Insect Physiol. 30, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiroi, M., Marion-Poll, F. & Tanimura, T. (2002) Zool. Sci. 19, 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meunier, N., Marion-Poll, F., Rospars, J. P. & Tanimura, T. (2003) J. Neurobiol. 56, 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nayak, S. V. & Singh, R. N. (1983) Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 12, 273–291. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayak, S. V. & Singh, R. N. (1985) Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 14, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lienhard, M. C. & Stocker, R. F. (1987) J. Exp. Zool. 244, 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanbhag, S. R. & Singh, R. N. (1992) Cell Tissue Res. 267, 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clyne, P. J., Warr, C. G. & Carlson, J. R. (2000) Science 287, 1830–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunipace, L., Meister, S., McNealy, C. & Amrein, H. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 822–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott, K., Brady, R., Cravchik, A., Morozov, P., Rzhetsky, A., Zuker, C. & Axel, R. (2001) Cell 104, 661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoon, M. A., Adler, E., Lindemeier, J., Battey, J. F., Ryba, N. J. P. & Zuker, C. S. (1999) Cell 96, 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler, E., Hoon, M. A., Mueller, K. L., Chandrashekar, J., Ryba, N. J. P. & Zuker, C. S. (2000) Cell 100, 693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandrashekar, J., Mueller, K. L., Hoon, M. A., Adler, E., Feng, L., Guo, W., Zuker, C. S. & Ryba, N. J. P. (2000) Cell 100, 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahanukar, A., Foster, K., van der Goes van Naters, W. M. & Carlson, J. R. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1182–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueno, K., Ohta, M., Morita, H., Mikuni, Y., Nakajima, S., Yamamoto, K. & Isono, K. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1451–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chyb, S., Dahaukar, A., Wickens, A. & Carlson, J. R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14526–14530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, Z., Singhvi, A., Kong, P. & Scott, K. (2004) Cell 117, 981–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorne, N., Chromey, C., Bray, S. & Amrein, H. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 1065–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brand, A. H. & Perrimon, N. (1993) Development 118, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi, S., Ito, K., Sado, Y., Taniguchi, M., Akimoto, A., Takeuchi, H., Aigaki, T., Matsuzaki, F., Nakagoshi, H. & Tanimura, T., et al. (2002) Genesis 34, 58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiroi, M., Meunier, N., Marion-Poll, F. & Tanimura, T. (2004) J. Neurobiol. 61, 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanbhag, S. R., Park, S. K., Pikielny, C. W. & Steinbrecht, R. A. (2001) Cell Tissue Res. 304, 423–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datta, S. & Kankel, D. R. (1992) Genetics 130, 523–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrich, M. V. K., Schneider, M., Timpl, R. & Baumgartner, S. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 3149–3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awasaki, K. & Kimura, K. (1997) J. Neurobiol. 32, 707–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitamoto, T. (2001) J. Neurobiol. 47, 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweeney, S. T., Broadie, K., Keane, J., Niemann, H. & O'Kane, C. J. (1995) Neuron 14, 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellen, H. J., D'evelyn, D., Harvey, M. & Elledge, S. J. (1992) Development 114, 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han, D. D., Stein, D. & Stevens, L. M. (2000) Development 127, 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roman, G., Endo, K., Zong, L. & Davis, R. L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12602–12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, T., Lee, A. & Luo, L. (1999) Development 126, 4065–4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura, K., Shimozawa, T. & Tanimura, T. (1986) J. Exp. Zool. 239, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marion-Poll, F. (1996) Entomol. Exp. Appl. 80, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.