Abstract

Among hundreds of mutants constructed systematically by the Japanese groups participating in the functional analysis of the Bacillus subtilis genome project, we found that a mutant with inactivation of iolT (ydjK) exhibited a growth defect on myo-inositol as the sole carbon source. The putative product of iolT exhibits significant similarity with many bacterial sugar transporters in the databases. In B. subtilis, the iolABCDEFGHIJ and iolRS operons are known to be involved in inositol utilization, and its transcription is regulated by the IolR repressor and induced by inositol. Among the iol genes, iolF was predicted to encode an inositol transporter. Inactivation of iolF alone did not cause such an obvious growth defect on inositol as the iolT inactivation, while simultaneous inactivation of the two genes led to a more severe defect than the single iolT inactivation. Determination of inositol uptake by the mutants revealed that iolT inactivation almost completely abolished uptake, but uptake by IolF itself was slightly detectable. These results, as well as the Km and Vmax values for the IolT and IolF inositol transporters, indicated that iolT and iolF encode major and minor inositol transporters, respectively. Northern and primer extension analyses of iolT transcription revealed that the gene is monocistronically transcribed from a promoter likely recognized by ςsgr;A RNA polymerase and negatively regulated by IolR as well. The interaction between IolR and the iolT promoter region was analyzed by means of gel retardation and DNase I footprinting experiments, it being suggested that the mode of interaction is quite similar to that found for the promoter regions of the iol divergon.

myo-Inositol is abundant in soil, and several microorganisms, including Bacillus subtilis (24), Cryptococcus melibiosum (22), Klebsiella aerogenes (3), and Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae (16), can grow on inositol as the sole carbon source. It has been thought that bacterial inositol catabolism is required only for efficient utilization of this compound. However, it was recently reported that in Sinorhizobium fredii, a functional inositol dehydrogenase, which catalyzes the first reaction of inositol catabolism, is also required for efficient nitrogen fixation and competitiveness to nodulate soybeans (11). This implies an interesting relationship between bacterial inositol catabolism and plant-bacterium symbiosis for nitrogen fixation.

Inositol catabolism in K. aerogenes has been studied extensively, a catabolic pathway for inositol yielding acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate together with specific enzymes involved in it being revealed (1-4). However, our knowledge of the molecular genetics for the catabolism has been restricted to only B. subtilis (24, 26). In B. subtilis the iol divergon, comprising the iolABCDEFGHIJ and iolRS operons, is involved in inositol catabolism (24); iolG encodes inositol dehydrogenase (7, 18, 24). Transcription of the iol divergon is regulated by a repressor encoded by iolR. In the absence of inositol in the growth medium, the IolR repressor binds to the iol operators to repress transcription, while in its presence inositol is taken into the cells and converted to an intermediate that acts as an inducer, which in turn antagonizes the operator binding of IolR to induce the iol divergon (26).

Specific enzymes involved in inositol catabolism have been studied, as mentioned above, but inositol uptake has not yet been investigated in any bacteria. Among the iol genes whose functions were deduced through a similarity search, iolF has been proposed to encode an inositol transporter (24), but the involvement of IolF in inositol uptake has remained unproven experimentally.

The completion of the whole genome sequencing of B. subtilis revealed 4,100 protein-coding genes (12), but the products of nearly half of the genes remain unspecified. Aiming at identification of the functions of the unspecified genes, an international project involving Japan and Europe, the functional analysis of the B. subtilis genome, was organized (28). Each of the participating groups is responsible for inactivation of the unspecified genes in a certain region of the chromosome to produce a series of inactivation mutants. All the mutants produced are shared among the corresponding groups carrying out intensive screening for categorized phenotypes. Within the framework of the project, we are responsible for the screening of phenotypes as to carbon source utilization of the mutants constructed by the Japanese groups and have chosen inositol as one of various carbon sources used for this screening.

Here we report that our phenotype screening has revealed that iolT (formerly called ydjK) is required for inositol utilization. Both iolT and iolF have been found to encode inositol transporters, but IolT plays a major role in inositol uptake. In addition, iolT, which is located apart from the iol divergon, is regulated by the IolR repressor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth media, and oligonucleotide primers.

All B. subtilis and Escherichia coli strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. B. subtilis strain IOLTd (YDJKd) is one of the mutant strains constructed during the functional analysis of the B. subtilis genome project (28); detailed information can be found at the JAFAN website (http://bacillus.genome.ad.jp). For construction of plasmids, E. coli strain DH5α (20) was used as the cloning host. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (20) containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml when needed. B. subtilis strains were precultured on tryptose blood agar base (Difco) supplemented with 0.18% glucose (TBABG) and grown in S6 medium (6). The antibiotics used for the selection of B. subtilis transformants were erythromycin (0.3 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), and the required amino acids were supplemented at 50 μg/ml. The oligonucleotides used for PCR and primer extension analysis are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 20 |

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F" [traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] | 23 |

| B. subtilis | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | Wild type |

| 60015 | trpC2 metC7 | Wild type (lab stock) |

| IOLTda | iolT::pMUTIN2 trpC2 | Y. Sadaie |

| FU350 | ΔiolF trpC2 | This work |

| FU351 | ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2 trpC2 | This work |

| FU352 | ΔiolF iolR::cat trpC2 | This work |

| FU353 | iolR::cat iolT::pMUTIN2 trpC2 | This work |

| FU354 | ΔiolF iolR::cat iolT::pMUTIN2 trpC2 | This work |

| YF244 | metC7 iolR::cat trpC2 | 24 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCP112 | Amprcat | 17 |

| pIOLR3 | pUC19 carrying iolR | 26 |

| pMUTIN2 | Ampr ErmrlacZ lacI | 21 |

| pUC19 | AmprlacZM15 | 23 |

This strain was formerly called YDJKd, which was constructed and deposited in the mutant collection by Y. Sadaie, Department of Molecular Biology, Saitama University, Saitama, Japan.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this work

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5"-3")a |

|---|---|

| dFF | GCGGTTTATCATTATGGGTC/GTGATCGGCATCAATAACGG |

| dFR | CCGTTATTGATGCCGATCAC/GACCCATAATGATAAACCGC |

| E-E | CCGGAATTCAAACAGCGGAAGAAGTGGAC |

| E-X | CCGCTCGAGAAACAGCGGAAGAAGTGGAC |

| G-B | CGCGGATCCACCTTTTGTGCAGCTTCTTG |

| G-X | CCGCTCGAGACCTTTTGTGCAGCTTCTTG |

| iolTFP1 | AGATTTTTGACTTGATTCACAC |

| iolTFP2 | CTCACATTTCGTAAGCAGGC |

| SP6-ydjK | ATTTAGGTGACACTATAGTTGGCTATGATACCGGTGTG |

| T7-ydjK | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCTCTGCTAAATAGGCAGGC |

| ydjK-1 | ATCTATTCCAGGGCTGCTGC |

| ydjK-2 | TGTCAATCCCTATGGAAGCG |

The created restriction sites used for cloning are underlined. The junction point of the in-frame deletion introduced into iolF is indicated by slashes. The T7 promoter tag sequence is given in italics.

Construction of B. subtilis mutants.

Strain FU350 carrying an in-frame deletion of codons 40 to 326 of the original 439 codons of iolF was constructed as follows. First, a 1.0-kb long EX fragment connecting two 0.5-kb DNA segments, one on either side of the net deletion, to join the 5"- and 3"-distal regions of iolF, with flanking EcoRI and XhoI sites at the upstream and downstream ends, respectively, was amplified by recombinant PCR (10), using chromosomal DNA from 60015 as a template and four primers: a pair of upstream and downstream primers (E-E and G-X, respectively; Table 2), and a pair of complementary overlapping primers, dFF and dFR, which covered the junction of the in-frame deletion (Table 2). Second, another XB fragment, identical to the EX fragment except that it had XhoI and BamHI sites at the upstream and downstream ends, respectively, was amplified as above using another pair of upstream and downstream primers (E-X and G-B; Table 2) and the same pair of complementary overlapping primers. Third, all the upstream and downstream ends of the EX and XB fragments were trimmed at the respective flanking restriction sites and then tripartitely ligated with the arm of plasmid pCP112 that had been cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI.

Plasmid pCP112 replicates in E. coli but not in B. subtilis, and its cat gene is expressed in B. subtilis. The resulting recombinant plasmid was then linearized by digestion with XhoI so that the pCP112 region was sandwiched between the XB and EX stretches. This linear DNA was used to transform 60015 (trpC2 metC7) to chloramphenicol resistance on TBABG plates through a double-crossover event that occurred at both the head part of the XB stretch and the tail of the EX one. In the chromosome of such transformants, thus, the original iolF-coding region was replaced with the two stretches, each carrying the iolF in-frame deletion, which flanked the pCP112 region. One of the transformants, in which the correct replacement had been confirmed, was further transformed with DNA from strain 168 (trpC2) to select chloramphenicol-sensitive colonies among Met+ transformants, which resulted from intrachromosomal recombination between the duplicated iolF in-frame deletion stretches to pinch out the pCP112 region, one copy of the deletion stretch thus being retained. One of the chloramphenicol-sensitive transformants was confirmed by DNA sequencing to carry the iolF in-frame deletion and was designated strain FU350 (Table 1).

Strain FU351 with simultaneous inactivation of iolT and iolF was constructed by transforming strain FU350 with DNA from IOLTd to erythromycin resistance (Table 1).

iolR inactivation was achieved for strains IOLTd, FU350, and FU351 by transforming them with DNA from strain YF244 (iolR::cat) to give them chloramphenicol resistance, yielding strains FU353, FU352, and FU354, respectively (Table 1).

Measurement of inositol uptake.

Inositol uptake by strains of B. subtilis was measured essentially by the method described previously (8). After cells had been grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 in S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids (Difco) with and without 10 mM inositol, 6 ml of the culture was harvested and washed in S6 medium plus chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml). The washed cells were suspended in 4 ml of the same medium plus chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml) and then used for measurements. Inositol uptake assays were performed with final inositol concentrations of 50 and 500 μM. The assay tubes held 0.7 ml of S6 medium plus chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml) containing myo-[U-14C]inositol (2.22 and 22.2 kBq, 9,457.2 MBq/mmol) (NEN Life Science Products) and 93 and 930 μM inositol, respectively, and were kept warm at 37°C. Inositol uptake was initiated by the addition of 0.6 ml of the cell suspension to each assay tube. After incubation at 37°C for 1, 2, or 3 min, as indicated, the suspension was filtered on a moistened glass microfiber filter (2.4-cm diameter) (GF/C; Whatman). The filter was immediately washed three times with 5 ml of S6 medium plus chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml). The filter was dried, and radioactivity was counted in 10 ml of ACSII scintillant (Amersham).

Northern and primer extension analyses.

Total RNA was extracted and purified from B. subtilis cells as described previously (27). For Northern analysis, a DNA fragment corresponding to part of iolT, with a flanking T7 RNA polymerase promoter tag at the downstream end, was amplified by PCR using the primer pair SP6-ydjK and T7-ydjK (Table 2), and DNA from 60015 as a template. The PCR product was subjected to in vitro transcription driven by T7 RNA polymerase to obtain a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probe, using a DIG RNA labeling kit (SP6/T7) (Roche Diagnostics). The RNA samples prepared from cells were electrophoresed, transferred to a nylon membrane, hybridized with the RNA probe, and then washed as described (27). The chemiluminescent signal on the membrane was detected with a DIG luminescence detection kit (Roche Diagnostics).

Primer extension analysis was performed as described previously (27). Reverse transcription was begun from the ydjK-2 primer (Table 2), which had been labeled at its 5" terminus by means of a Megalabel kit (Takara Shuzo) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham). A template for the dideoxy sequencing reactions begun from the same end-labeled primer for ladder preparation was prepared by PCR using the primer pair ydjK-1 and ydjK-2 (Table 2), and DNA from 60015 as a template.

Gel retardation and DNase I footprinting experiments.

Gel retardation and DNase I footprinting experiments were performed as described (26). The IolR protein was produced in E. coli JM109 carrying pIOLR3, and the crude extract was used for the experiments as described (26). The probe DNA for the gel retardation and DNase I footprinting experiments was prepared by PCR amplification of a DNA stretch containing the 5"-flanking region of iolT using DNA from 60015 as a template and a pair of specific primers (iolTFP1 and iolTFP2; Table 2), either of which had been labeled at the 5" terminus with a Megalabel kit and [γ-32P]ATP prior to the PCR amplification.

RESULTS

Inactivation of iolT caused a significant growth defect on inositol as the sole carbon source.

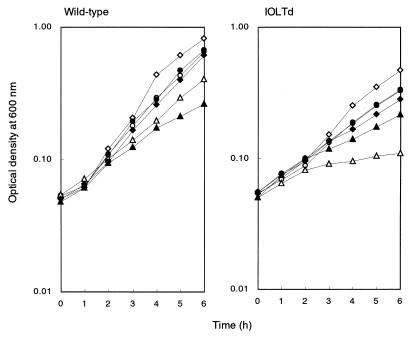

We carried out screening of phenotypes of carbon source utilization for the mutants constructed by the Japanese groups participating in the functional analysis of the B. subtilis genome project (28). We evaluated the mutants for utilization of various carbon sources by means of their colony formation on plate media (refer to the JAFAN website, http://bacillus.genome.ad.jp) and found that 10 of 872 mutants exhibited some growth defect on inositol. Among these mutants, strain IOLTd (YDJKd), with inactivation of iolT (ydjK), showed the most severe and specific growth defect on inositol. The growth defect of IOLTd was confirmed by means of a liquid culture test (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Growth of the B. subtilis strain with iolT inactivation on various carbon sources. Cells of strains 168 (wild-type, left) and IOLTd (right) were inoculated into S6 medium containing 25 mM fructose (open circles), 25 mM glucose (open diamonds), 50 mM glycerol (solid circles), 25 mM inositol (open triangles), 37.5 mM malate (solid diamonds), or 30 mM ribose (solid triangles) and supplemented with 0.02% Casamino Acids and then allowed to grow at 37°C with shaking. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the OD600. The data obtained in a single experiment are shown. The experiments were each repeated at least three times, with similar results.

IOLTd exhibited an apparent growth defect on inositol, while it could grow almost normally on other carbon sources such as fructose, glucose, glycerol, malate, and ribose. Therefore, iolT appeared to be specifically involved in inositol utilization. Moreover, the putative gene product of iolT exhibits significant similarity to various bacterial sugar transporters in the databases, including the xylose-proton symporter of Lactobacillus brevis (5) and galactose-proton symporter of E. coli (19). These results thus implied that iolT might encode a transporter for inositol uptake.

The iolT gene was negatively regulated by the IolR repressor.

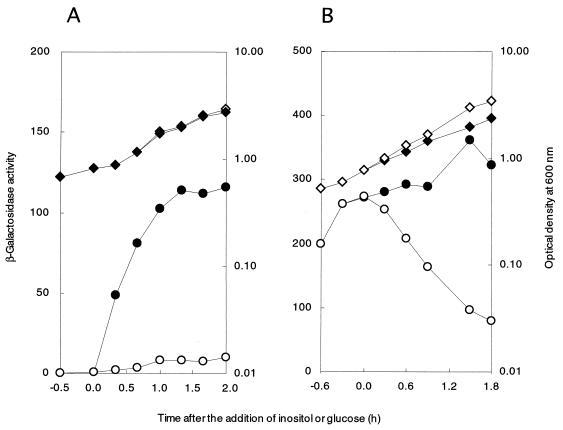

iolT in strain IOLTd was inactivated by integration of plasmid pMUTIN2 (21), which carries a lacZ reporter to monitor iolT expression. When strain IOLTd was grown without inositol, the β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity in the cells was negligible (Fig. 2A). However, when inositol was added to the same culture, it drastically increased the β-Gal activity, indicating that transcription of iolT was induced by inositol.

FIG. 2.

Expression of the lacZ reporter in cells of B. subtilis strains with iolT inactivation. (A) Growth and expression of the lacZ reporter of B. subtilis strain IOLTd. Strain IOLTd cells were inoculated into S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids and allowed to grow for 0.5 h at 37°C with shaking. Then the culture was divided into two parts, and 10 mM inositol was added to one of them. The cultures were incubated continuously, and the OD600 of the cultures (no addition, open diamonds; inositol, solid diamonds) and β-Gal activity in cell extracts (nanomoles per minute per milligram of protein) (no addition, open circles; inositol, solid circles) were monitored as described previously (28). (B) Growth and expression of the lacZ reporter of strain FU353 (iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat). The experiments with B. subtilis strain FU353 were performed as above, except that 10 mM glucose or inositol was added at 0.6 h after inoculation [OD600, solid (inositol) and open (glucose) diamonds; β-Gal activity, solid (inositol) and open (glucose) circles]. The data obtained in a single experiment are shown. The experiments were each repeated at least three times, with similar results.

The B. subtilis iol divergon (i.e., the iolABCDEFGHIJ and iolRS operons), involved in inositol catabolism, is repressed by the IolR repressor and induced by inositol (24, 26). To investigate the possibility that IolR might regulate iolT, the expression of iolT was examined in the iolR-null background as above (Fig. 2B). The β-Gal activity in cells of strain FU353 (iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat) was very high even in the absence of inositol, suggesting that iolT was negatively regulated by IolR. In addition, glucose addition decreased the activity drastically (Fig. 2B), implying that iolT expression might be under catabolite repression.

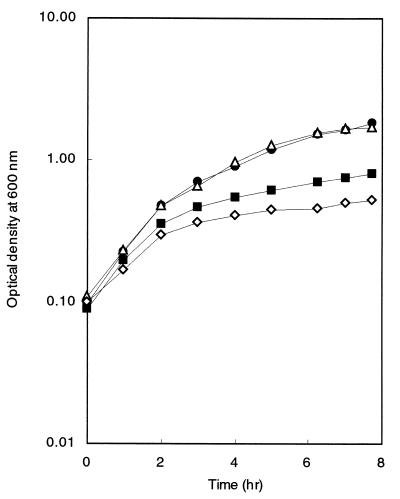

Inactivation of iolF led to a less obvious growth defect than that of iolT.

The sixth gene of the iol operon, iolF, was predicted to encode a transporter protein (24) as well as iolT. We thus inactivated iolF by means of an in-frame deletion (ΔiolF) to avoid a possible polar effect on the expression of downstream genes. The in-frame deletion was designed to remove 287 internal codons (codons 40 to 326) from the original 439 codons of iolF, which eliminated the two putative sugar transporter motifs (http://bacillus.genome.ad.jp). When growth of strain FU350 (ΔiolF) on inositol was examined, it turned out that the iolF inactivation did not cause as great a growth defect as iolT inactivation (Fig. 3). However, another mutant, FU351, in which both iolF and iolT were inactivated simultaneously showed a more severe growth defect than that with the single iolT inactivation (Fig. 3). These results indicated that iolF was likely involved in inositol transport, while the growth defect caused by the iolF inactivation was only observed in the iolT-null background.

FIG. 3.

Growth of B. subtilis mutants (iolT::pMUTIN2 and ΔiolF) on inositol as the sole carbon source. Cells of B. subtilis strains 60015 (wild-type, solid circles), IOLTd (iolT::pMUTIN2, solid squares), FU350 (ΔiolF, open triangles), and FU351 (ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2, open diamonds) were inoculated into S6 medium containing 25 mM inositol and 0.02% Casamino Acids and allowed to grow at 37°C with shaking. The OD600 of the cultures was monitored. The data obtained in a single experiment are shown. The experiments were each repeated at least three times, with similar results.

Inositol dehydrogenase, encoded by iolG, the seventh gene of the iol operon, is induced in the presence of inositol (24). The enzyme was induced in the mutant with the single inactivation of iolF by almost the same amount as in the wild type (Table 3). On the contrary, iolT inactivation alone caused a significant decrease in induction, and the simultaneous inactivation of the two led to a more obvious decrease. The lower inducibility of the enzyme caused by the mutation of iolT and iolF correlated well with the above observation as to the growth defect.

TABLE 3.

Inositol dehydrogenase synthesis in B. subtilis strainsa

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Inositol dehydrogenase activity (nmol per min per mg of protein) in cells grown:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Without inositol | With inositol | ||

| 60015 | Wild type | 5.7 | 180.3 |

| FU350 | ΔiolF | 4.4 | 155.0 |

| IOLTd | iolT::pMUTIN2 | 4.6 | 89.1 |

| FU351 | ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2 | 4.4 | 49.7 |

| YF244 | iolR::cat | 893.4 | 359.8 |

| FU352 | ΔiolF iolR::cat | 779.9 | 312.7 |

| FU353 | iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat | 716.6 | 518.9 |

| FU354 | ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat | 585.0 | 621.6 |

Cells of B. subtilis strains were grown in S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids, with and without 10 mM inositol. The cells (4.5 OD600 units) were harvested and then treated with lysozyme and sonicated briefly to prepare crude extracts. Inositol dehydrogenase activity in the extracts was measured as described previously (15). Each value is the average of three determinations.

iolT expression can be monitored by measuring the β-Gal activity in the cells of strain IOLTd (iolT::pMUTIN2). The inducibility of β-Gal by inositol was compared between strains IOLTd and FU351 (iolT::pMUTIN2 ΔiolF) to examine if the iolF inactivation affects the induction. When the cells were exposed to 0.5 and 10 mM inositol for 30 min, the β-Gal activity decreased to 78 and 63% upon ΔiolF introduction, respectively (data not shown). This fact also implied that iolF was likely involved in inositol transport.

Defect in inositol uptake by iolT and iolF mutants.

To examine the involvement of iolT and iolF in inositol transport, we determined inositol uptake by the mutant B. subtilis strains (Fig. 4A). The inositol uptake into wild-type cells was induced in the presence of inositol in the culture medium. At an inositol concentration of 50 μM, the rates of uptake were calculated to be 0.65 and 0.16 nmol min−1 per OD600 unit with and without induction, respectively. The single iolF inactivation lowered the uptake slightly, but the single iolT inactivation and the simultaneous inactivation of iolT and iolF abolished it almost completely. These results suggested that iolT plays a major role in inositol uptake.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of inositol uptake by B. subtilis mutant strains (iolT::pMUTIN2 and ΔiolF). (A) Inositol uptake by cells of B. subtilis strains grown with and without inositol. Cells of B. subtilis strains 60015 (wild-type, open circles), IOLTd (iolT::pMUTIN2, open diamonds), FU350 (ΔiolF, solid circles), and FU351 (ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2, solid diamonds) were grown in S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids, with (right, induced) and without (left, not induced) 10 mM inositol. Inositol uptake was measured in the presence of 50 μM inositol as described in the text. (B) Concentration dependency of inositol uptake into B. subtilis cells carrying iolR::cat. Cells of B. subtilis YF244 (iolR::cat, open circles), FU353 (iolR::cat iolT::pMUTIN2, open diamonds), FU352 (ΔiolF iolR::cat, solid circles), and FU354 (ΔiolF iolR::cat iolT::pMUTIN2, solid diamonds) were grown in S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids. Inositol uptake was measured with inositol concentrations of 50 (left) and 500 (right) μM. The data obtained in a single experiment are shown. The experiments were each repeated at least twice, with similar results.

To determine the inositol uptake caused by IolT and IolF more precisely, we carried out inositol uptake experiments using iolT and iolF mutants carrying the iolR-null mutation, which rendered their expression constitutive (Fig. 4B); the constitutive expression of the iol genes in these mutants was confirmed by detection of the constitutive and high inositol dehydrogenase activities in them (Table 3). As expected, the iolR inactivation resulted in about a seven times higher rate of inositol uptake (the rate was 4.47 nmol min−1 per OD600 unit) compared with that into the cells of YF244 (iolR::cat) and 60015 (wild-type) grown without and with inositol, respectively. Even in the iolR-null background, iolF inactivation could only affect the uptake partially, but the iolT one alone was enough to almost completely abolish it (50 μM; Fig. 4B, left). However, when the inositol concentration in the assay medium was increased 10-fold (500 μM; Fig. 4B, right), strain IOLTd exhibited only slight but significant uptake, which could be attributed to IolF.

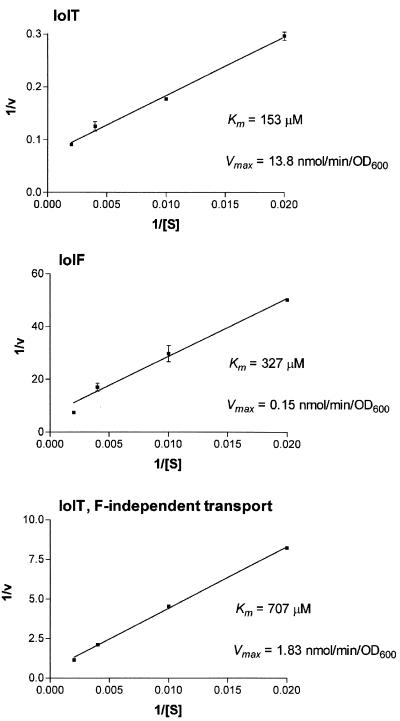

Thus, we determined the Km and Vmax values of inositol uptake by IolT, IolF, and IolTF-independent transporters by measuring inositol uptake at various inositol concentrations into the cells of strains FU352 (ΔiolF iolR::cat), FU353 (iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat), and FU354 (ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat) (Fig. 5). The Km and Vmax values of inositol uptake are shown in Fig. 5, indicating that the IolT transporter, which exhibited the lowest Km and highest Vmax, plays a major role in inositol uptake. These values also suggest that not only IolF but also an unknown IolTF-independent transporter is likely to contribute to inositol uptake at a higher inositol concentration. Overall, we concluded that iolT and iolF encode major and minor inositol transporters, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Lineweaver-Burk plots for determination of Km and Vmax values of inositol uptake by IolT, IolF, and IolTF-independent transporters. The rates of inositol uptake at various inositol concentrations ([S], micromolar) by the cells of strains FU352 (ΔiolF iolR::cat), FU353 (iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat), and FU354 (ΔiolF iolT::pMUTIN2 iolR::cat) were measured as described in the text. The uptake rates depending on IolT and IolF were obtained by subtracting the rates for strain FU354 from those for strains FU352 and FU353, respectively. The plots were generated from the results of the duplicated experiments. Km and Vmax values of inositol uptake by IolT, IolF, and IolTF-independent transporters are shown.

Transcription analyses of iolT.

RNA samples prepared from cells of strains 60015 (wild-type) and YF244 (iolR::cat) grown in the presence and absence of inositol were subjected to Northern analysis using an iolT-specific probe. As shown in Fig. 6A, a specific transcript was detected only when the wild-type cells grew in the presence of inositol, while a transcript of the same size was synthesized constitutively in the iolR mutant. The size of the transcript was estimated to be about 1.7 kb, which would just cover the iolT open reading frame, suggesting that iolT is a monocistronic operon. The strong and specific signals corresponding to smaller RNAs which are absent in lane 3 (strain 60015, without inositol) appeared to result from RNA degradation. The results indicated that transcription of iolT was negatively regulated by IolR and induced by inositol, which was consistent with the results of the iolT expression analysis with lacZ as the reporter (Fig. 2). Primer extension analysis mapped the 5" end of the iolT transcript (Fig. 6B) and allowed us to find a corresponding promoter sequence consisting of −10 (TATGAT, where the −10 position is underlined) and −35 (TTGACT) regions separated by a 17-bp spacer, which is likely recognized by ςsgr;A RNA polymerase (9).

FIG. 6.

Northern and primer extension analyses of the iolT transcript. (A) Northern analysis. RNA samples were extracted and purified from cells of strains 60015 (wild-type, lanes 3 and 4) and YF244 (iolR::cat, lanes 1 and 2) grown in S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids, with (lanes 2 and 4) and without (lanes 1 and 3) 10 mM inositol. The positions of size markers are indicated on the left. The iolT transcript is indicated by an arrow on the right. (B) Primer extension analysis. The RNA from cells of strains 60015 (lanes 3 and 4) and YF244 (lanes 1 and 2) grown in S6 medium containing 0.5% Casamino Acids, with (lanes 2 and 4) and without (lanes 1 and 3) 10 mM inositol was the same as that used for the above Northern analysis. Lanes G, A, T, and C contained the products of the respective dideoxy sequencing reactions performed with the same primer as that used for the primer extension. On the right, the reverse transcript of iolT is indicated by an arrow. On the left, part of the sequence of the noncoding strand of the iolT promoter region is shown, where the transcription start point (+1) is indicated, and the −10 and −35 regions are underlined.

Determination of the IolR-binding site within the iolT promoter region.

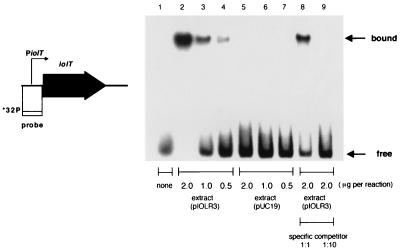

As described above, iolT expression is regulated by IolR. We thus investigated the interaction between IolR and the iolT promoter region by means of gel retardation analysis, using IolR produced in E. coli cells and a labeled DNA probe covering nucleotide positions −139 to +224 (+1 is the iolT transcription initiation nucleotide). As shown in Fig. 7, the probe became increasingly retarded as the amount of IolR-containing extract in the assay mixture was increased, forming a band corresponding to a protein-DNA complex, and the addition of an excess amount of unlabeled DNA identical to the probe abolished the complex formation with the labeled probe. The results indicated that the cis element interacting with IolR was located in the 363-bp region.

FIG. 7.

Gel retardation analysis of IolR binding to the iolT promoter region. The probe DNA, which was 32P labeled at the 5" end of the noncoding strand, is schematically shown on the left. For gel retardation analysis, cell extracts were prepared from cells of E. coli strain JM109 bearing plasmid pIOLR3 or pUC19 grown with 1 mM IPTG as described previously (26). Each lane contained 0.02 pmol of the 32P-labeled probe DNA and an excess amount of fragmented calf thymus DNA (3.3 μg) in a 25-μl reaction mixture. Lane 1 contained no protein extract. Lanes 2, 8, and 9, lane 3, and lane 4 contained 2.0, 1.0, and 0.5 μg of the protein extract of cells bearing pIOLR3, respectively, whereas lanes 5, 6, and 7 contained 2.0, 1.0, and 0.5 μg of that of cells bearing pUC19, respectively. Lanes 8 and 9 also contained 0.02 and 0.2 pmol of the nonlabeled probe DNA as a specific competitor, respectively. The IolR-DNA complex (bound) and free probe (free) are indicated on the right.

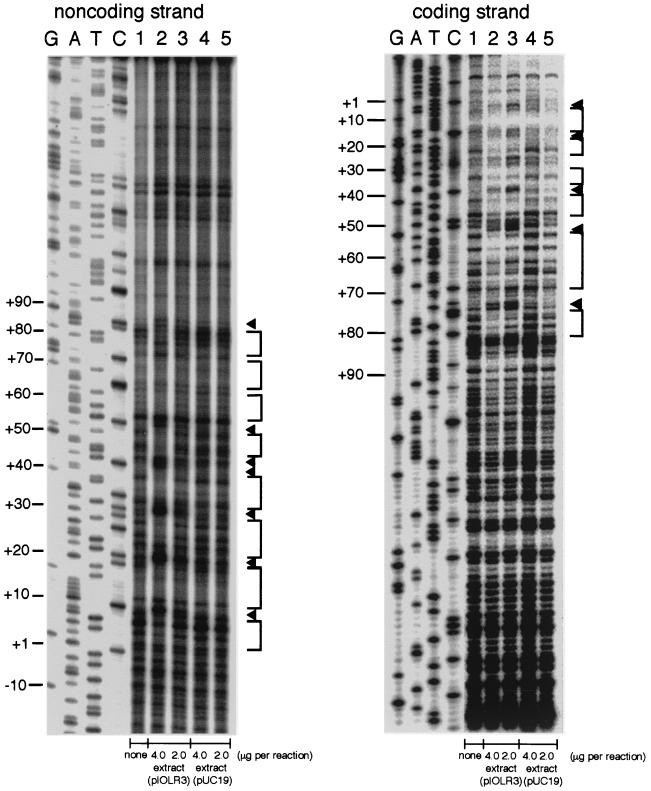

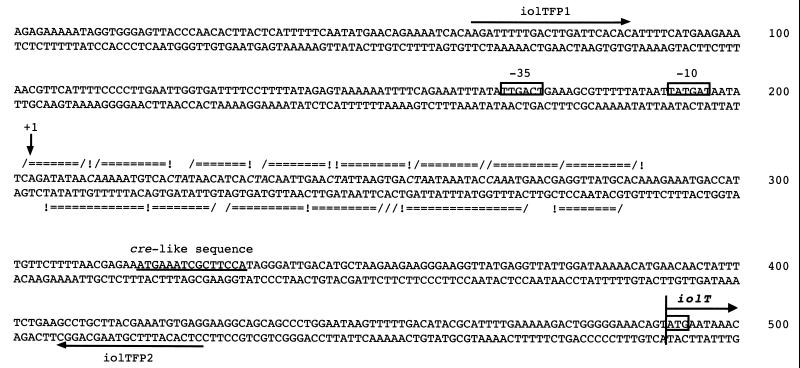

The interaction between IolR and this region was further analyzed by means of DNase I footprinting experiments using the same DNA fragment as for the gel retardation analysis (Fig. 8). The specific interaction on the noncoding strand was observed in an extended region from positions +1 to +85, while that on the coding strand was observed from +3 to +81 (Fig. 9). Similar DNase I digestion patterns were seen for each of the strands, with the appearance of alternating protected and hypersensitive sites. The sensitive sites were located at approximately 10-nucleotide intervals, coinciding with each pitch of the DNA helix, so the sites on both strands could be aligned and projected on one side of the helix. These characteristics of DNase I digestion upon IolR binding well resembled those observed in the cases of the iol and iolRS promoter regions reported previously (26). The specific interaction with IolR was observed only in the region (positions +1 to +85) on the footprinting experiments which contained a sequence resembling those of the iol operators described previously (26).

FIG. 8.

DNase I footprinting analysis of the interaction of IolR with the extended iolT promoter region. The left and right panels are DNase I footprints of the 5"-end-labeled noncoding and coding strands, respectively, of the probe DNA prepared as described in the text. Lanes 1 to 5 contained 0.04 pmol of the 32P-labeled probe DNA in the reaction mixture (50 μl). Lane 1 contained no protein extract. Lanes 2 and 3 contained 4.0 and 2.0 μg of the protein extract of JM109 cells bearing pIOLR3, respectively, whereas lanes 4 and 5 contained 4.0 and 2.0 μg of that of cells bearing pUC19, respectively. Lanes G, A, T, and C contained the products of the respective sequencing reactions performed with the respective primers as those used for the probe preparation. The enhanced cleavage sites and protected regions are indicated by arrowheads and vertical lines on the right of each panel, respectively, and nucleotide numbers are shown on the left (+1 is the transcription start nucleotide of iolT).

FIG. 9.

Summary of the results of DNase I footprinting analysis. The nucleotide sequences of the noncoding and coding strands of the extended iolT promoter region are given, with indication of protected (=), hypersensitive (!), and sensitive even without IolR (/) sites observed in the footprints. The primers (iolTFP1 and iolTFP2) used for the probe preparation are indicated by horizontal arrows. The transcription start point (+1) is indicated by a vertical arrow. The −10 and −35 regions of the promoter are boxed in the noncoding strands. The conserved periodic CAA or CTA triplets (see text) are given in italics. The cre-like sequence is underlined beneath the sequence of the noncoding strand. The iolT translation starts from the boxed ATG.

DISCUSSION

The iolT inactivation led to a growth defect specifically on inositol as the carbon source (Fig. 1), while the iolF one alone did not (Fig. 3). The simultaneous inactivation of the two genes, however, caused a more serious defect than the single iolT inactivation (Fig. 3), suggesting that the effect of the iolF inactivation was so minor that it could only be seen in the iolT-null background. The measurement of inositol uptake by the cells revealed that each of the iolT and iolF inactivations could affect inositol uptake into the cells (Fig. 4). Especially in the case of the iolT inactivation, inositol uptake was almost abolished even when iolF was active. These results as well as the Km and Vmax values of inositol uptake by IolT and IolF inositol transporters (Fig. 5) led us to conclude that iolT and iolF encoded primary and secondary transporters for inositol uptake, respectively.

Under our inositol uptake assay conditions, the contribution of IolF by itself was slightly detectable only with a higher concentration of inositol (500 μM; Fig. 4B, right), suggesting the possibility that iolF could encode a transporter with lower affinity for the substrate. We determined the Km values of inositol uptake by the IolT and IolF inositol transporters (Fig. 5), indicating that the value of the former was lower than that of the latter. Thus, IolF could support growth on inositol partially with an inositol concentration of 10 mM in the iolT background (Fig. 3). In addition, as shown in Table 3, even when iolT was inactivated, inositol dehydrogenase activity increased to approximately half the level in the wild type, and the activity decreased further with the additional iolF inactivation. The iolF inactivation also affected the inducibility of β-Gal of the reporter of iolT expression in strain IOLTd. These results indicated that a certain amount of inositol must have been taken up into the cells by the IolF transporter and then converted to an intermediate acting as an inducer. Thus, inositol uptake only by the IolF transporter was not enough to support the normal growth on inositol (Fig. 3).

On the other hand, even when both transporter genes were inactivated simultaneously, inositol dehydrogenase was induced up to about one-fourth the level in the wild type. This partial induction of the iol operon appeared to coincide with the slow growth on inositol (Fig. 3), which might be due to the presence of other inositol transporters. Actually, this unknown IolTF-independent inositol transport, which exhibited the highest Km value compared with those of IolT and IolF, was likely to contribute to inositol uptake at a higher inositol concentration (Fig. 5). Within the B. subtilis genome, there are 47 paralogous genes, including iolT and iolF, most of which remain unspecified. Some such paralogous transporters might have a broad specificity that allows them to import some amount of inositol at a higher concentration.

The iolABCDEFGHIJ operon is under glucose repression, which is exerted through catabolite repression, mediated by the CcpA protein, and the iol induction system, mediated by the IolR repressor (25). Very recently, catabolite repression involving two distinct catabolite-responsive elements (cre) was extensively investigated (13). As indicated by the expression profile of the lacZ reporter used to monitor iolT expression (Fig. 2), iolT was repressed by glucose, suggesting that iolT could be catabolite repressive. This repression was achieved independently of regulation mediated by the IolR repressor, since the repression by glucose was observed even in the iolR-null background. Within the downstream DNA sequence of the iolT promoter region, there is a cre-like sequence (ATGAAATCGCTTCCA, Fig. 8) at positions +116 to +130 (14). This cre-like sequence might play a role in the catabolite repression of iolT through interaction with the CcpA/effector complex (14).

As shown in Fig. 2, 4, and 6, transcription of iolT was negatively regulated by IolR. Also, the gel retardation and DNase I footprinting analyses clearly indicated specific binding of IolR to the extended region close to the iolT transcription initiation nucleotide that is most likely to be an iolT operator (Fig. 7, 8, and 9). The patterns of DNase I cleavage on both the DNA strands resembled those found in our previous work on the interaction between IolR and the iol and iolRS promoter regions (26). The sequence of the IolR-interacting stretch showed phasing of A+T- and G+C-rich periodicities, which were shifted by approximately one-half of a helical turn with respect to each other. Also, the G+C-rich periodicity appeared to almost coincide with the DNase I cleavage sites. Thus, similar to the previous findings for the iol and iolRS promoter regions (26), IolR interacted with the DNA of the iolT region in such a way that the minor groove of the A+T-rich sequences points in toward IolR, while that of the G+C-rich sequences points away from the IolR.

The previous work had led us to the hypothesis that a tandem direct repeat of a relatively conserved 11-mer sequence, WRAYCAADARD, might determine the IolR-DNA interaction (26), but such a direct repeat was not conserved in the extended iolT promoter region interacting with IolR. Instead, comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the three regions interacting with IolR allowed us to find conserved periodic triplets of CAA or CTA separated from each other by an 8-bp-long spacer (Fig. 9); in the cases of the iol and iolRS regions, the triplet corresponded to the conserved CAA at the 5th to 7th positions within the 11-mer sequence of the direct repeat. In all three cases, the DNase I-sensitive sites predominated at the first C of the triplets, implying that the triplets might take on a specific configuration upon the IolR-DNA interaction. Thus, the conserved periodic CAA/CTA triplets might be the determining elements in the DNA sequence that enable the specific binding of IolR. Moreover, the overall sequence property of the phasing of A+T- and G+C-rich periodicities may also be a remarkable character of the IolR-interacting regions, which might reflect a specific three-dimensional structure of DNA responsible for the tight binding of IolR to it.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Takeda, M. Yamada, and S. Yamada for their technical assistance. We also thank K. Asai, Department of Molecular Biology, Saitama University, Japan, for plasmid pCP112 and valuable suggestions for construction of the iolF in-frame deletion mutant.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for the Encouragement of Young Scientists to K. Yoshida, and in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (C) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, W. A., and B. Magasanik. 1971. The pathway of myo-inositol degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. Identification of the intermediate 2-deoxy-5-keto-d-gluconic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 246:5653-5661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, W. A., and B. Magasanik. 1971. The pathway of myo-inositol degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. Conversion of 2-deoxy-5-keto-d-gluconic acid to glycolytic intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 246:5662-5675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman, T., and B. Magasanik. 1966. The pathway of myo-inositol degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. Dehydrogenation and dehydration. J. Biol. Chem. 241:800-806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman, T., and B. Magasanik. 1966. The pathway of myo-inositol degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. Ring scission. J. Biol. Chem. 241:807-813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaillou, S., Y. C. Bor, C. A. Batt, P. W. Postma, and P. H. Pouwels. 1998. Molecular cloning and functional expression in Lactobacillus plantarum 80 of xylT, encoding the d-xylose-H+ symporter of Lactobacillus brevis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4720-4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita, Y., and E. Freese. 1981. Isolation and properties of a Bacillus subtilis mutant unable to produce fructose-bisphosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 145:760-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita, Y., K. Shindo, Y. Miwa, and K. Yoshida. 1991. Bacillus subtilis inositol dehydrogenase-encoding gene (idh): sequence and expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 108:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita, Y., J. Nihashi, and T. Fujita. 1986. The characterization and cloning of a gluconate (gnt) operon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haldenwang, W. G. 1995. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Rev. 59:1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higuchi, R. 1990. Recombinant PCR, p. 177-183. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 11.Jiang, G., A. H. Krishnan, Y.-M. Kim, T. J. Wacek, and H. B. Krishnan. 2001. A functional myo-inositol dehydrogenase gene is required for efficient nitrogen fixation and competitiveness of Sinorhizobium fredii USDA191 to nodulate soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). J. Bacteriol. 183:2595-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunst, F., et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miwa, Y., and Y. Fujita. 2001. Involvement of two distinct catabolite-responsive elements in catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis myo-inositol (iol) operon. J. Bacteriol. 183:5877-5884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miwa, Y., A. Nakata, A. Ogiwara, M. Yamamoto, and Y. Fujita. 2000. Evaluation and characterization of catabolite-responsive elements (cre) of Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1206-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nihashi, J., and Y. Fujita. 1984. Catabolite repression of inositol dehydrogenase and gluconate kinase syntheses in Bacillus subtilis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 798:88-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poole, P. S., A. Blyth, C. J. Reid, and K. Walters. 1994. myo-Inositol catabolism and catabolite regulation in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. Microbiology 140:2787-2795. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price, C. W., M. A. Gitt, and R. H. Doi. 1983. Isolation and physical mapping of the gene encoding the major sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:4074-4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaley, R., Y. Fujita, and E. Freese. 1979. Purification and properties of Bacillus subtilis inositol dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 254:7684-7690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts, P. E. 1992. The galactose/H+ symport protein of Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 20.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Vagner, V., E. Dervyn, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 144:3097-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidal-Leiria, M., and N. van Uden. 1973. Inositol dehydrogenase from the yeast Cryptococcus melibiosum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 293:295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strain: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida, K., D. Aoyama, I. Ishio, T. Shibayama, and Y. Fujita. 1997. Organization and transcription of the myo-inositol operon, iol, of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:4591-4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida, K., K. Kobayashi, Y. Miwa, C. Kang, M. Matsunaga, H. Yamaguchi, S. Tojo, M. Yamamoto, R. Nishi, N. Ogasawara, T. Nakayama, and Y. Fujita. 2001. Combined transcriptome and proteome analysis as a powerful approach to study genes under glucose repression in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:683-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida, K., T. Shibayama, D. Aoyama, and Y. Fujita. 1999. Interaction of a repressor and its binding sites for regulation of the Bacillus subtilis iol divergon. J. Mol. Biol. 285:917-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida, K., Y. Fujita, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1999. Three asparagine synthetase genes of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:6081-6091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida, K., I. Ishio, E. Nagakawa, Y. Yamamoto, M. Yamamoto, and Y. Fujita. 2000. Syst. study of gene expression and transcription organization in the gntZ-ywaA region of the Bacillus subtilis genome. Microbiology 146:573-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]