Abstract

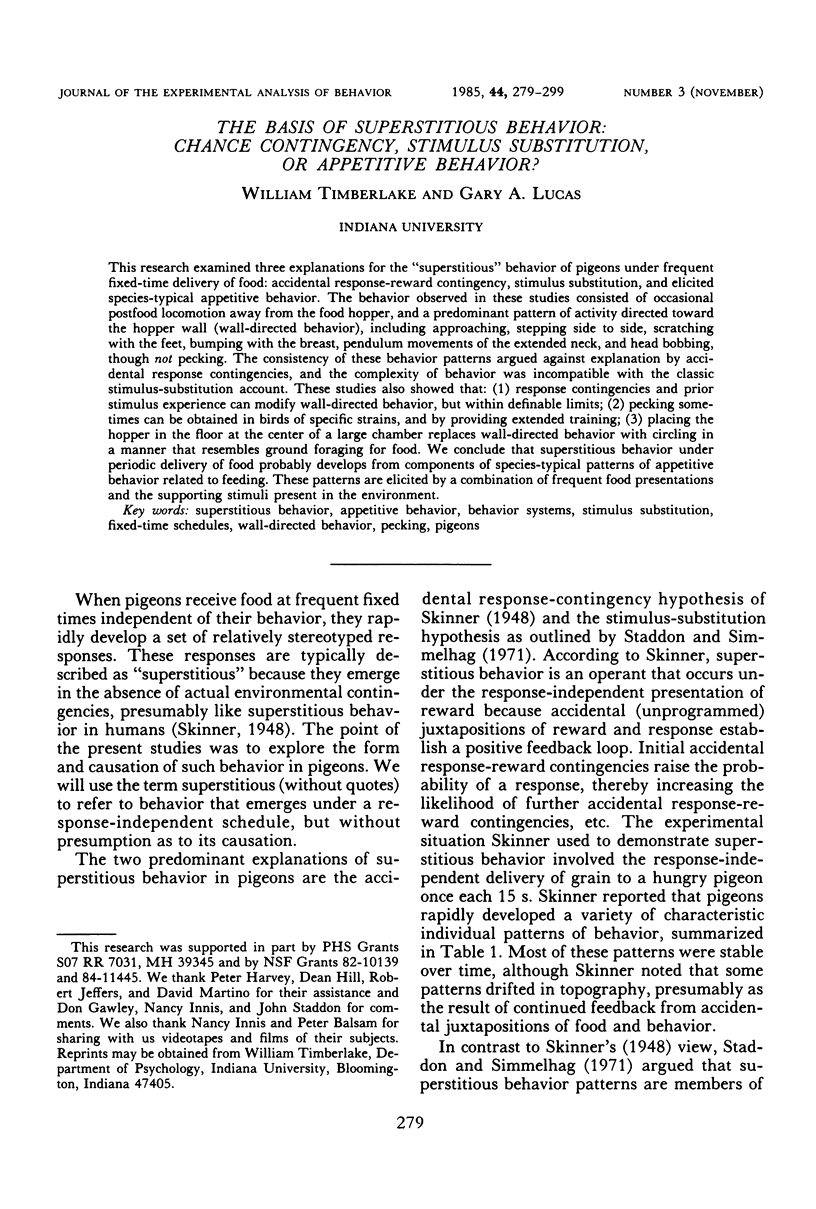

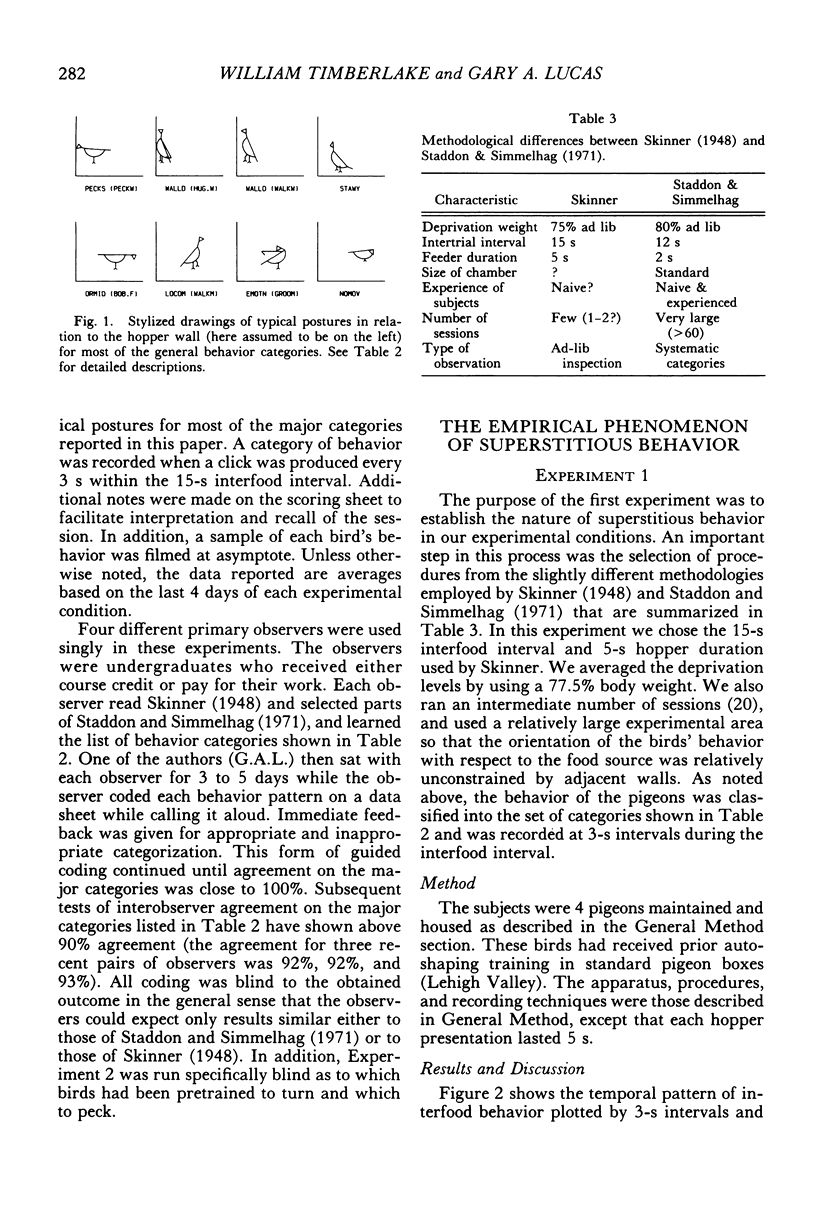

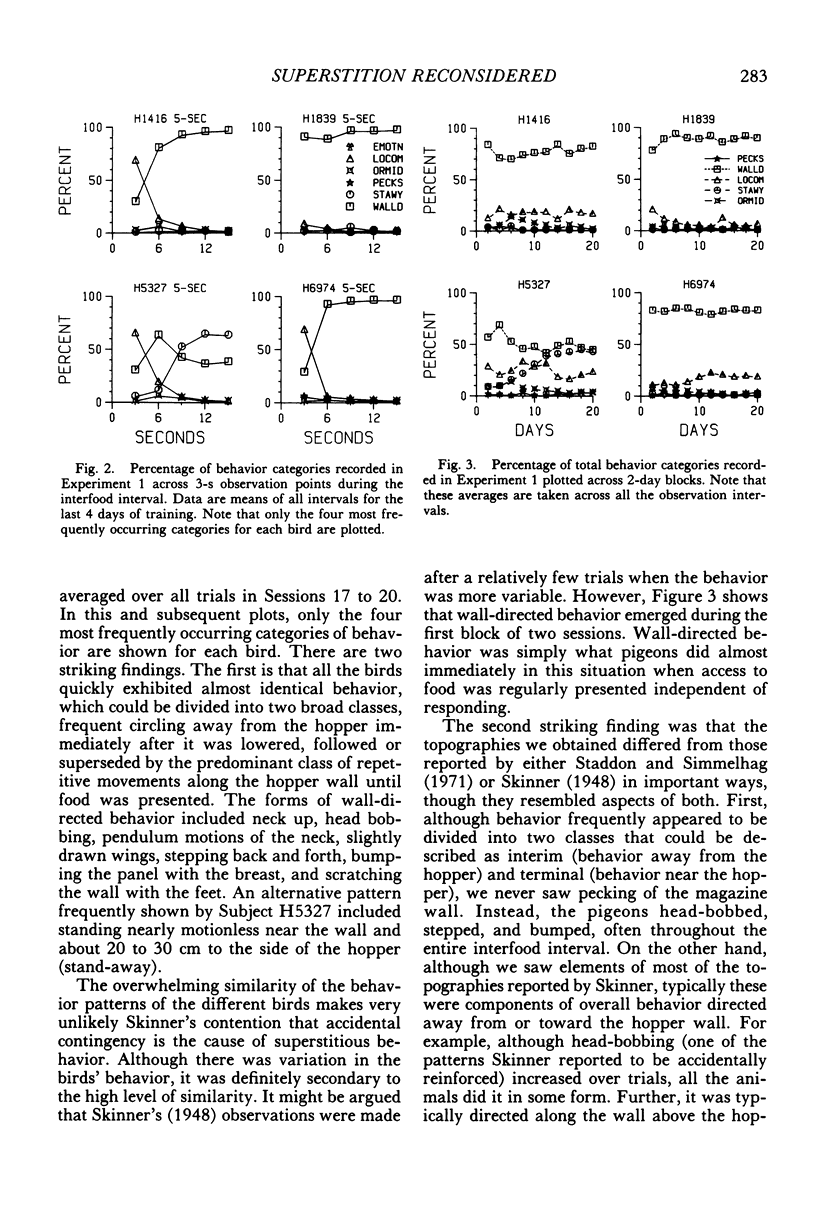

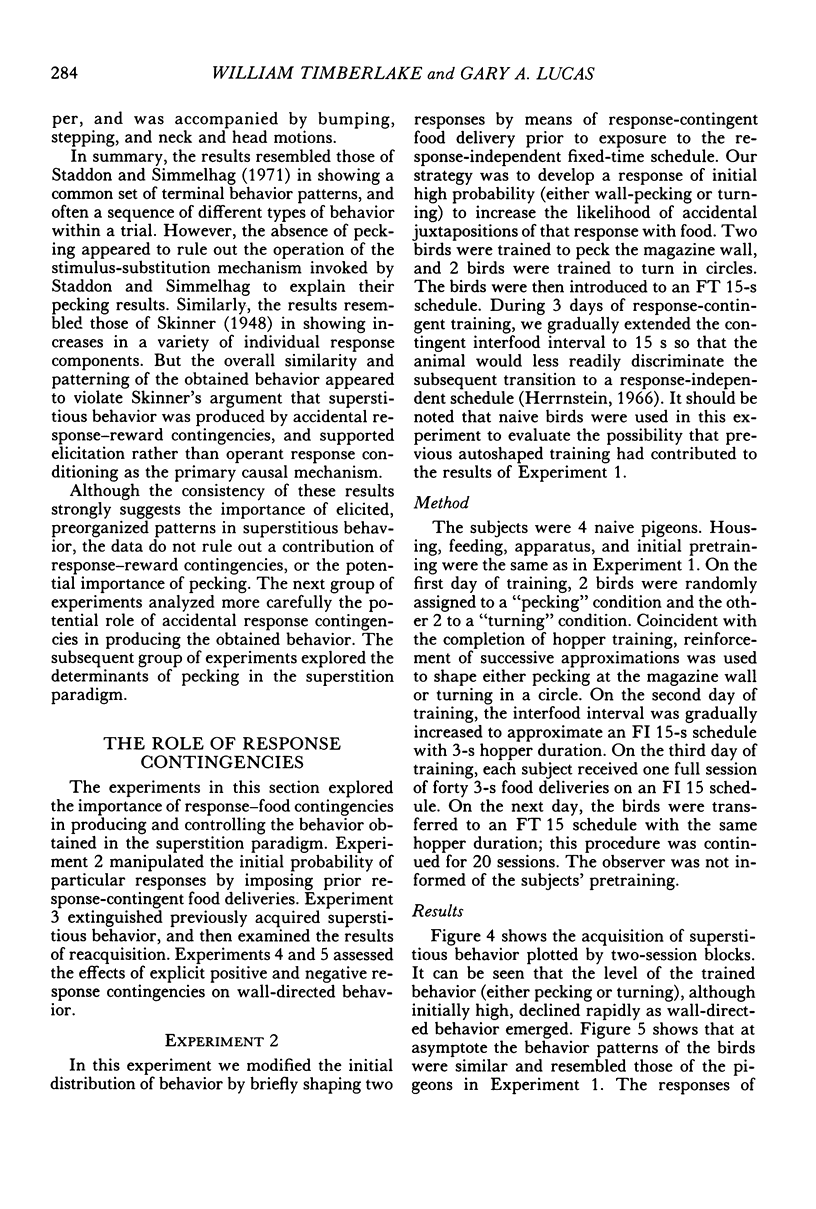

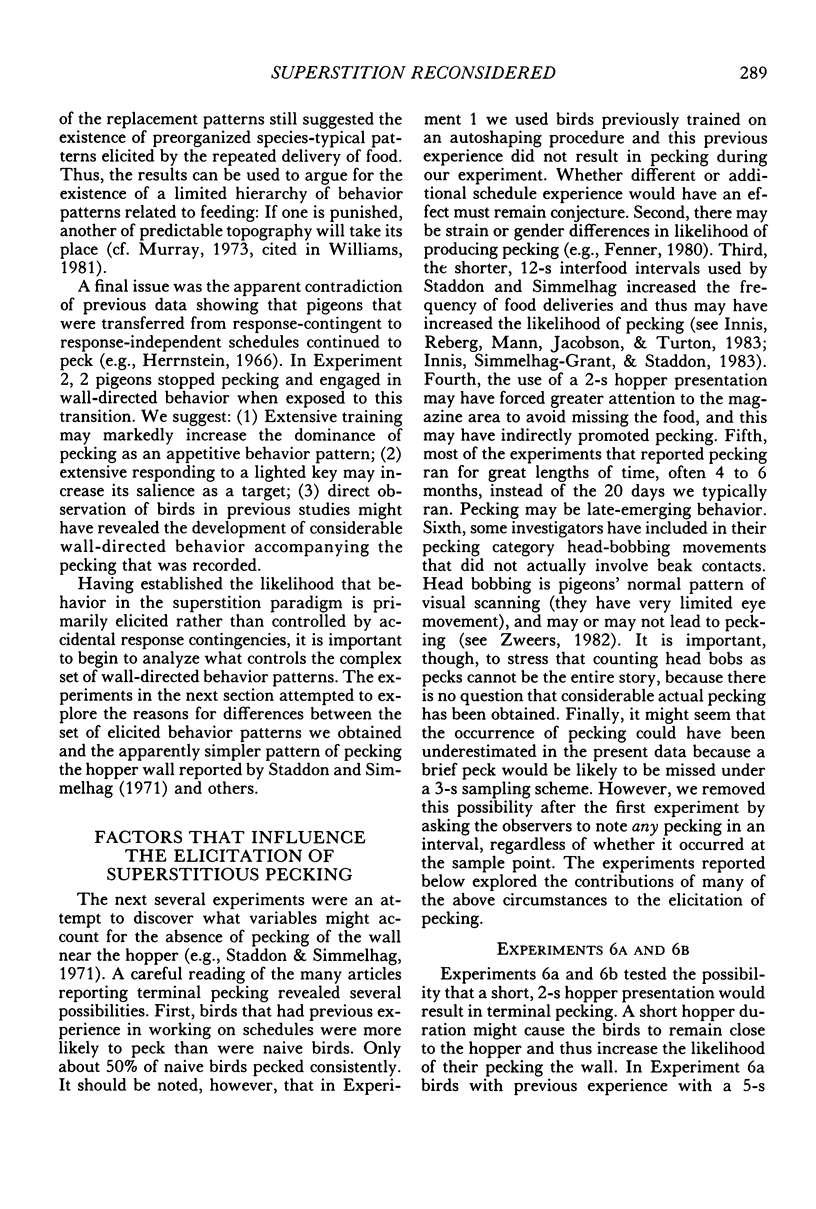

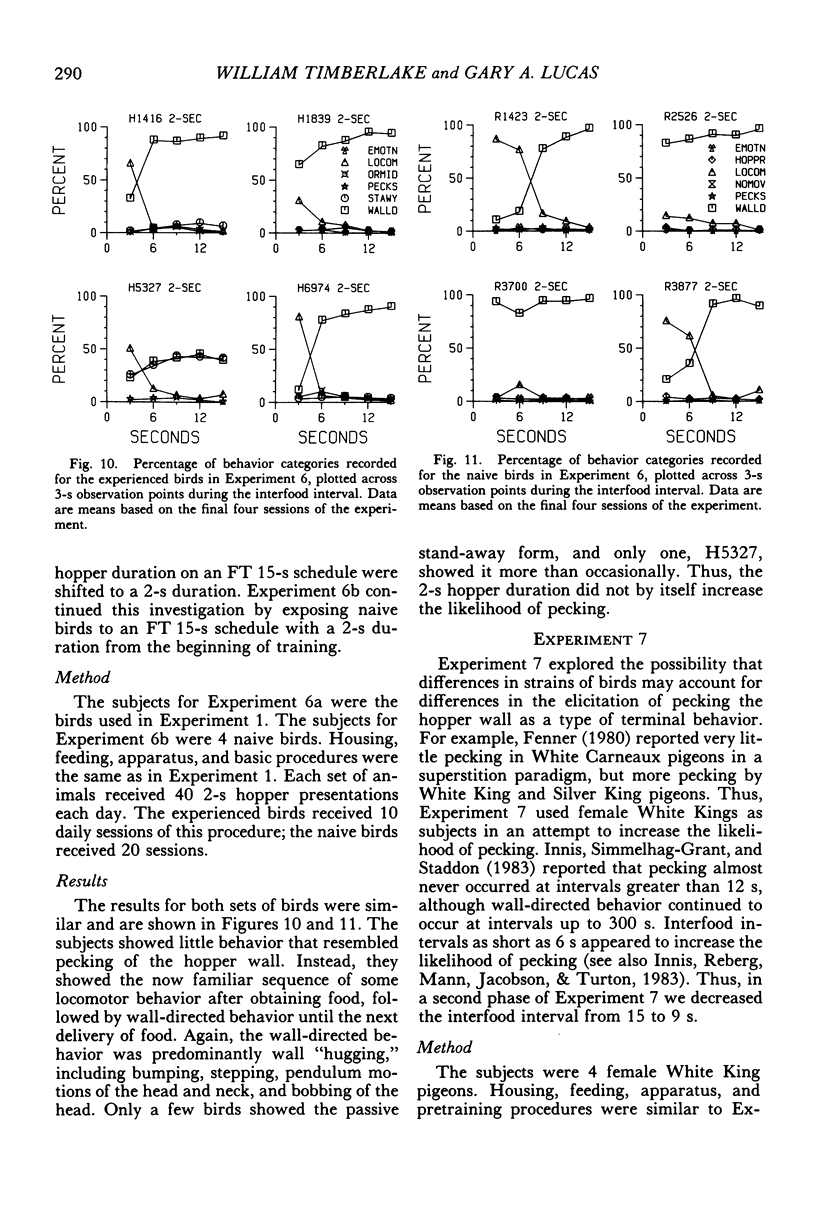

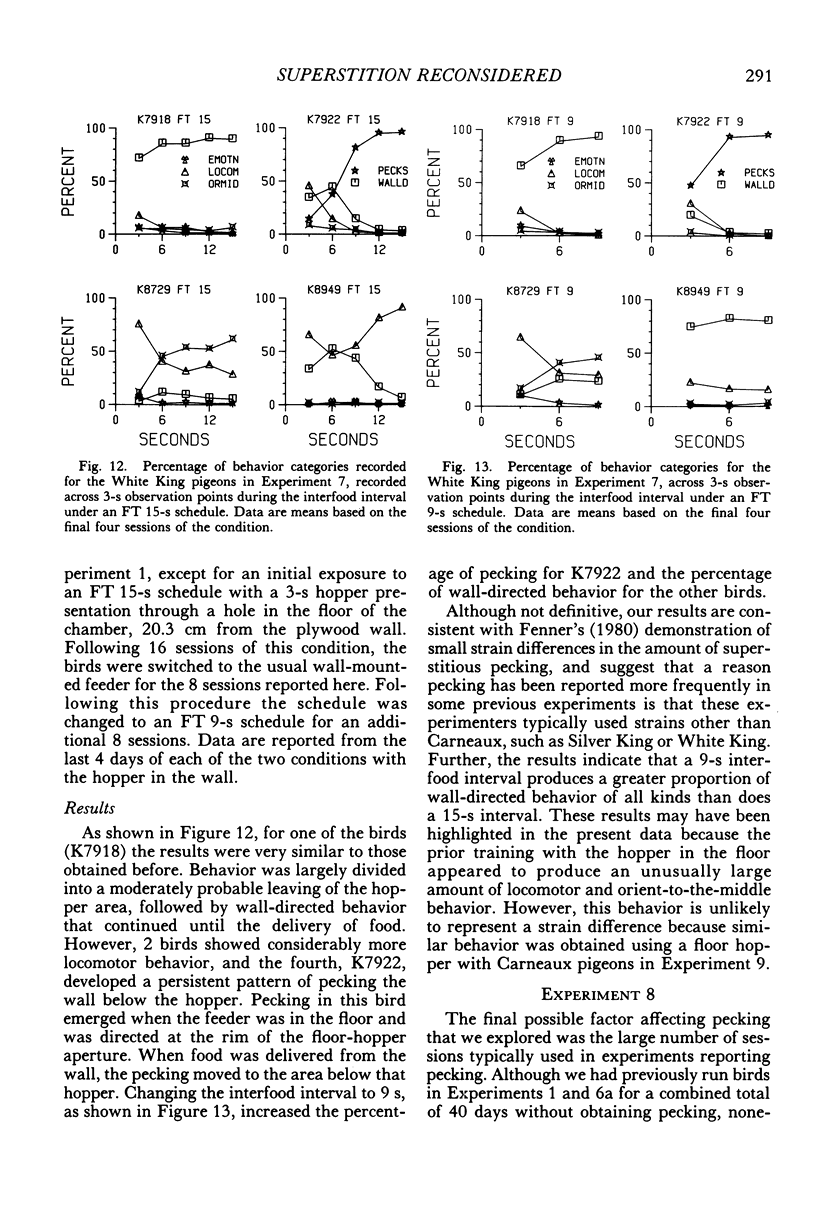

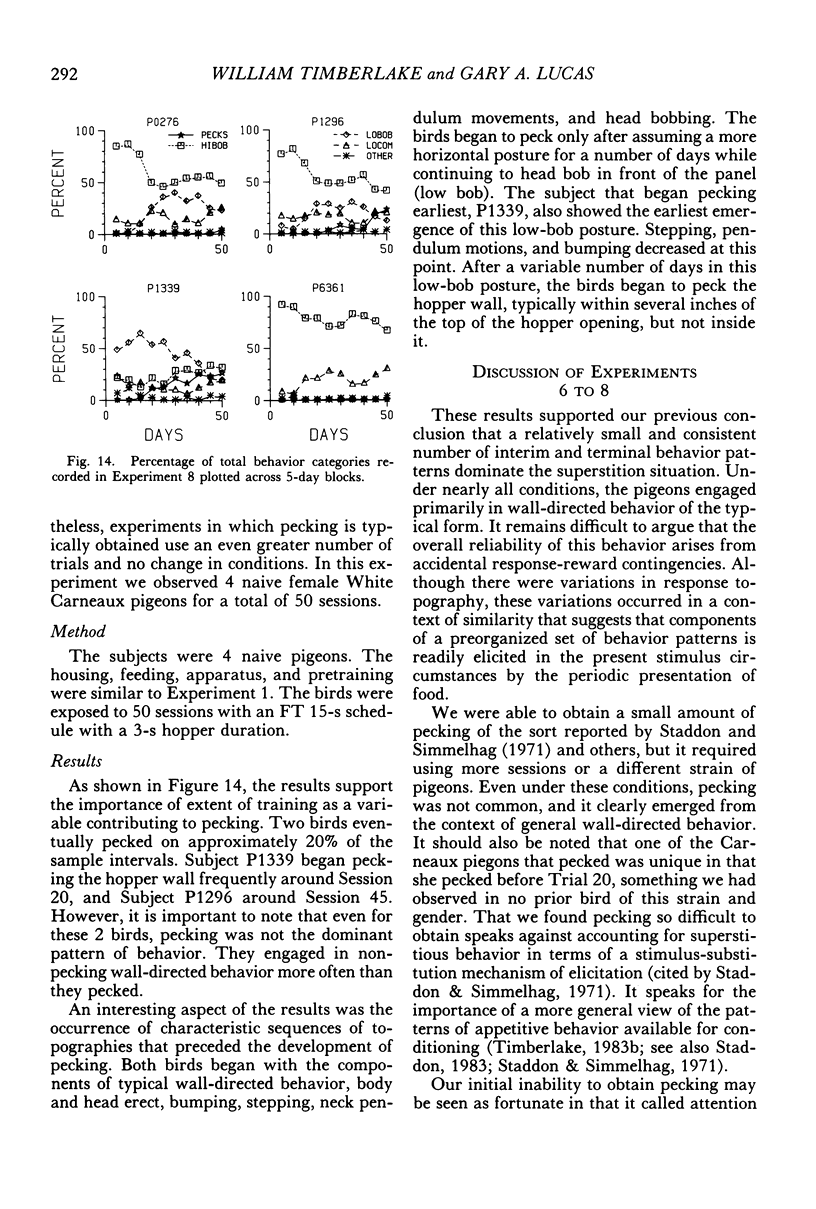

This research examined three explanations for the "superstitious" behavior of pigeons under frequent fixed-time delivery of food: accidental response-reward contingency, stimulus substitution, and elicited species-typical appetitive behavior. The behavior observed in these studies consisted of occasional postfood locomotion away from the food hopper, and a predominant pattern of activity directed toward the hopper wall (wall-directed behavior), including approaching, stepping side to side, scratching with the feet, bumping with the breast, pendulum movements of the extended neck, and head bobbing, though not pecking. The consistency of these behavior patterns argued against explanation by accidental response contingencies, and the complexity of behavior was incompatible with the classic stimulus-substitution account. These studies also showed that: (1) response contingencies and prior stimulus experience can modify wall-directed behavior, but within definable limits; (2) pecking sometimes can be obtained in birds of specific strains, and by providing extended training; (3) placing the hopper in the floor at the center of a large chamber replaces wall-directed behavior with circling in a manner that resembles ground foraging for food. We conclude that superstitious behavior under periodic delivery of food probably develops from components of species-typical patterns of appetitive behavior related to feeding. These patterns are elicited by a combination of frequent food presentations and the supporting stimuli present in the environment.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baerends G. P. On drive, conflict and instinct, and the functional organization of behavior. Prog Brain Res. 1976;45:425–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner D. The role of contingencies and "principles of behavioral variation" in pigeons' pecking. J Exp Anal Behav. 1980 Jul;34(1):1–12. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1980.34-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis N. K., Simmelhag-Grant V. L., Staddon J. E. Behavior induced by periodic food delivery: The effects of interfood interval. J Exp Anal Behav. 1983 Mar;39(2):309–322. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1983.39-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins H. M., Moore B. R. The form of the auto-shaped response with food or water reinforcers. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973 Sep;20(2):163–181. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORSE W. H., SKINNER B. F. Some factors involved in the stimulus control of operant behavior. J Exp Anal Behav. 1958 Jan;1:103–107. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1958.1-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reberg D., Mann B., Innis N. K. Superstitious behavior for food and water in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1977 Dec;19(6):803–806. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake W., Wahl G., King D. Stimulus and response contingencies in the misbehavior of rats. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1982 Jan;8(1):62–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Williams H. Auto-maintenance in the pigeon: sustained pecking despite contingent non-reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Jul;12(4):511–520. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]