Abstract

The amf gene cluster was previously identified as a regulator for the onset of aerial-mycelium formation in Streptomyces griseus. The nucleotide sequences of amf and its counterparts in other species revealed a conserved gene organization consisting of five open reading frames. A nonsense mutation in amfS, encoding a 43-amino-acid peptide, caused significant blocking of aerial-mycelium formation and streptomycin production, suggesting its role as a regulatory molecule. Extracellular-complementation tests for the aerial-mycelium-deficient phenotype of the amfS mutant demonstrated that AmfS was secreted by the wild-type strain. A null mutation in amfBA, encoding HlyB-like membrane translocators, abolished the extracellular AmfS activity without affecting the wild-type morphology, which suggests that AmfBA is involved not in production but in export of AmfS. A synthetic C-terminal octapeptide partially induced aerial-mycelium formation in the amfS mutant, which suggests that an AmfS derivative, but not AmfS itself, serves as an extracellular morphogen.

The filamentous, soil-inhabiting, gram-positive bacterial genus Streptomyces is characterized by the ability both to undergo complex cellular differentiation resembling that of filamentous fungi and to produce a wide variety of secondary metabolites (4-6). The morphological and physiological development of the organism is controlled by complex regulatory circuits consisting of various regulatory proteins. In the streptomycin-producing species Streptomyces griseus, both morphological differentiation and antibiotic production are regulated by an autoregulatory hormonal substance, A-factor (2-isocapryloyl-3 R-hydroxymethyl-γ-butyrolactone) (9-11). The autoregulator induces the transcription of adpA, the central positive regulator, by inactivating ArpA, which acts as a transcriptional repressor for adpA (18, 19). AdpA then pleiotropically induces the transcription of genes, such as adsA (29) and strR (25, 26), encoding specific positive transcriptional regulatory proteins for morphogenesis and streptomycin biosynthesis, respectively.

We previously identified the amf gene cluster as a positive regulator for the onset of aerial-mycelium formation in S. griseus (23, 24). The amf region, which induced aerial-mycelium formation in an A-factor-deficient mutant strain, HH1, contained four complete open reading frames (ORFs); amfR encoded a response regulator of a two-component regulatory system, which is essential for the initiation of aerial-mycelium formation, and both amfA and amfB encoded ABC transporters homologous to HlyB of Escherichia coli (3). Additionally, a small possible ORF encoding a peptide consisting of 43 amino acids (aa) (ORF6) was present in front of amfB. The presence of amfA and amfR on a high-copy-number plasmid was sufficient for the restoration of the aerial mycelium in mutant HH1 (23). While AmfR was reasonably deduced to be a transcriptional regulator that may control the expression of genes involved in the onset of cell differentiation, the substrate of the transporters AmfA and AmfB was unclear. Here, we report mutational analysis of the small ORF, now named amfS. Several lines of evidence suggest that the gene product is modified and secreted by the AmfAB-mediated transport system to act as an extracellular peptidic morphogen.

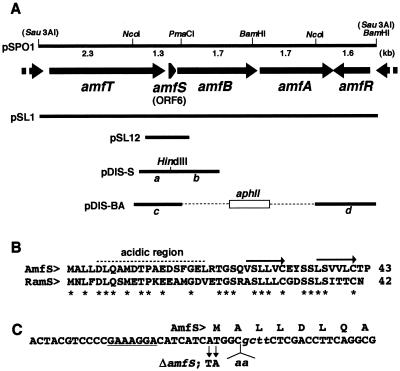

Gene organization of amf and its counterparts.

The original clone containing the amf cluster was a 9-kb Sau3AI fragment (Fig. 1A) (23). The nucleotide sequence of the region upstream from amfS revealed a large ORF, amfT, encoding a transmembrane protein of 891 aa that showed some similarity to Ser/Thr kinases (7). A subsequent homology search in the completed genomic database of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor/) revealed that the genes amfT-amfS-amfB-amfA-amfR were conserved in this organism (corresponding to SC5A7.31 to -35) and the homologous genes include the ORFs previously identified as ram. The ram gene cluster, consisting of ramABR (corresponding to amfBAR of S. griseus), is known to stimulate aerial-mycelium formation in Streptomyces lividans when introduced on a high-copy-number plasmid (12, 14). The gene cluster was also conserved in Streptomyces avermitilis, whose genome sequence has recently been completed (H. Ikeda and S. Ōmura, personal communication). We therefore assumed that the proteins encoded by the five ORFs have functional relationships in regulating aerial-mycelium formation.

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the 9-kb Sau3AI fragment and the positions and directions of ORFs in the fragment (A), amino acid alignment of AmfS and the homolog in S. coelicolor (B), and nucleotide sequence of a part of amfS (C). (A) The extents and directions of ORFs of the nucleotide sequence predicted by the FRAME program (2) are indicated by arrows. The positions of fragments used for gene disruption and complementation experiments are also shown. pSL1 and pSPO1 (23) carry the 9-kb fragment on a low-copy-number plasmid, pIJ922 (8), and a high-copy-number plasmid, pIJ487 (27), respectively. pSL12 carries the amfS-containing 700-bp region at the BamHI site of pIJ922. (B) The amino acid sequence of AmfS was aligned with the homologous sequence identified in S. coelicolor A3(2). The C-terminal hydrophobic repeats are indicated by arrows. Idential amino acids are indicated by asterisks. (C) Nucleotide sequence of the N-terminal portion of amfS with the deduced amino acid sequence. The potential site for ribosome binding is underlined. The mutated sequence used for the disruption of amfS (ΔamfS) is indicated below the wild-type sequence. The italic lowercase letters represent the recognition site for HindIII created to check for true recombination.

Figure 1B shows the sequence alignment of AmfS and its counterpart in S. coelicolor A3(2). The peptides carried an N-terminal acidic region and C-terminal repeats of hydrophobic sequences [(V/L)-S-(L/V)-(L/V)-(V/L)-C for AmfS]. The two C-terminal Cys residues conserved in the peptides might play a role important for the structure and function of the molecules. amfS and the homolog were preceded by an identical potential ribosome-binding sequence (GAAAGGA). These observations led us to assume that the small ORFs are translated into peptides and could be secreted via the function of the translocators to play some role for morphogenesis.

Inactivation of amfS.

To assess the role of amfS, we disrupted it by the homologous-recombination technique. The mutant was generated by using plasmid pDIS-S, which contained a mutated amfS sequence on pUC19 (Fig. 1A). The mutagenized construct, carrying both a nonsense mutation at the translational initiation codon and an insertion of two adenine residues creating a restriction site for HindIII endonuclease (Fig. 1C), was generated by combining the fragments a and b (Fig. 1A) (corresponding to nucleotides 7214 to 8093 and 6236 to 7217 of the submitted nucleotide sequence, respectively). These fragments were separately amplified by the standard PCR technique with the following primers: 5"-CCGAATTCCTCCGGATCATCCTCG-3" (the italic letters represent an EcoRI cleavage site for cloning into pUC19-KM) and 5"-GAG AAGCTTGCCTAGATGATGTCCTTTCGG-3" (the italic and underlined letters represent the HindIII cleavage site and the nonsense codon, respectively) for fragment a and 5"-GGC AAGCTTCTCGACCTTCAGGCGATGG-3" (the italic letters represent the HindIII site) and 5"-CGAGGATCCAGCAGCATGAGCAGG-3" (the italic letters represent a BamHI cleavage site for cloning into pUC19-KM) for fragment b. Fragments a and b were recovered as an EcoRI/HindIII- and a HindIII/BamHI-digested fragment, respectively, and combined by cloning between the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pUC19-KM by three-fragment ligation. pUC19-KM was generated by inserting an aphII kanamycin resistance gene cassette (1) amplified and recovered as a HindIII fragment by appropriate PCR at the HindIII site of pUC19 (30). The plasmid constructed in this way was introduced into S. griseus IFO13350 (a wild-type strain) by the standard transformation procedure, and the integrants carrying the plasmid-derived DNA inserted at the amfS locus via a single-crossover event were screened for among the resultant kanamycin-resistant colonies. The integrants isolated were checked for the correct recombination by Southern hybridization, and one of the true recombinants was then cultured in YMP-glucose liquid medium (containing [in grams per liter] yeast extract [Difco], 2; meat extract [Kyokuto], 2; Bacto Peptone [Difco], 4; NaCl [Kokusan], 5; MgSO4 [Kokusan], 2; and glucose [Kokusan], 10 [pH 7.2]) without kanamycin. The cells were then plated onto YMP-glucose solid medium (containing 1.5% agar [Kokusan] in YMP-glucose) after appropriate dilution, and kanamycin-sensitive recombinants generated by the second crossover were screened for among the resultant colonies. Consequently, three amfS mutants were isolated among the kanamycin-sensitive colonies, all of which showed the phenotype described below. The correct replacement of the wild-type amfS with the mutated construct was confirmed by Southern hybridization. The standard molecular recombination techniques in E. coli and Streptomyces spp. were described in the protocols by Maniatis et al. (15) and Hopwood et al. (8), respectively.

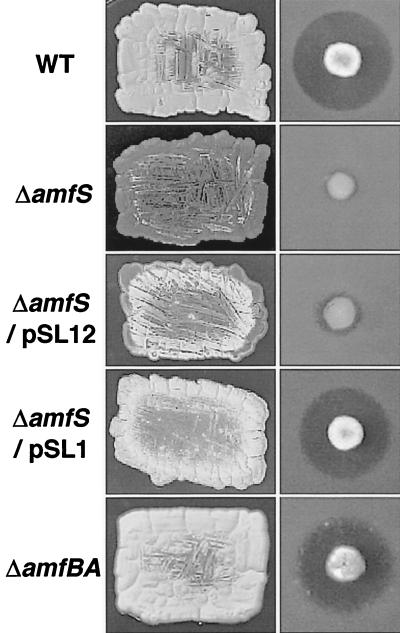

The resultant amfS mutant showed a bald phenotype (Fig. 2); on YMP-glucose solid medium, the amfS mutant was unable to form aerial mycelia. The deficiency was partially recovered on YMP-maltose medium (containing 1% maltose instead of the glucose in YMP-glucose medium), but aerial-mycelium formation was still significantly reduced (not shown). Streptomycin production was also markedly reduced on all the solid media tested. The phenotype of the mutant clearly indicates that amfS plays an important role in cellular differentiation and antibiotic production in S. griseus. The A-factor production assay using an A-factor-deficient mutant and Bacillus subtilis as indicators (11) showed that the amfS mutant normally produced A-factor. The deficiencies of the amfS mutant were rescued by the introduction of pSL1 (23) containing the whole gene cluster on a low-copy-number plasmid, pIJ922 (8). On the other hand, pSL12 containing the amfS coding region alone (Fig. 1A) partially restored the aerial mycelium, which suggests that amfS is mainly transcribed by the promoter preceding amfT. pSL12 was constructed by cloning the amfS-containing 700-bp BamHI fragment (corresponding to nucleotides 6925 to 7608) at the BamHI site of pIJ922, which was amplified by PCR with primers 5"-CG GGATCCGCCTTCTACGTCCAG-3" and 5"-GTGGAGCAGAGGAGGATCCCGAG-3" (the italic letters represent BamHI cleavage sites for cloning).

FIG. 2.

Phenotypes of the amfS and amfBA disruptants. For colony morphology (left), patches were photographed after 5 days of growth at 28°C on YMP-glucose medium. For streptomycin productivity (right), colonies were grown for 5 days at 28°C on YMP-maltose medium, overlaid with soft agar containing spores of B. subtilis, and incubated overnight at 37°C. WT, wild type.

A null mutant of amfBA.

An amfBA mutant was also generated as follows. The flanking fragments of amfBA (fragments c and d [Fig. 1A]) were prepared by appropriate restriction of pSPO1, the original plasmid carrying the 9-kb Sau3AI fragment at the BamHI site in the multilinker of pIJ487 (27), which enabled us to recover the Sau3AI fragment as an EcoRI-HindIII fragment. For fragment c, the Sau3AI-PmaCI region was recovered as an EcoRI-BglII fragment by attaching an 8-mer BglII linker at the PmaCI cleavage end. For fragment d, the NcoI-BamHI region was recovered as a BglII-HindIII fragment by blunt-end formation at the NcoI cleavage end with the Klenow fragment followed by attaching an 8-mer BglII linker. The fragments c and d were combined by cloning them between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pUC19 by three-fragment ligation. The resultant plasmid was cleaved with BglII and ligated to an aphII cassette prepared as a 0.9-kb BamHI fragment by an appropriate PCR procedure to generate pDIS-BA. The mutagenized construct was then recovered from pDIS-BA as an EcoRI/HindIII-digested fragment, and the linear DNA was introduced into S. griseus IFO13350 by the standard transformation procedure. The mutants were screened for among the resultant kanamycin-resistant colonies that carry the mutagenized construct via a double-crossover event. Subsequent checking by Southern hybridization with appropriate probes confirmed the true disruptant. In contrast to the bald phenotype of the amfS mutant, the resultant null mutant of amfBA showed the wild-type morphology and streptomycin productivity (Fig. 2).

Extracellular complementation.

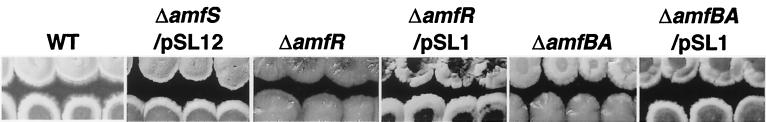

Extracellular-complementation tests with the amfS mutant as a recipient demonstrated the putative exogenous activity of the AmfS product (Fig. 3). The activity to form aerial mycelium was restored to the amfS mutant upon growth near the wild-type or the amfS mutant harboring pSL12, which suggests that the extracellular AmfS or its derivative supplied from the donor strains can complement the nonsense mutation in amfS to restore morphogenesis. On the other hand, the extracellular stimulatory activity was produced by neither the mutant for amfR (24) nor that for amfBA (this study). The activities in those mutants were restored by the introduction of pSL1, which confirmed that the deficiencies are linked to each mutation. These results indicate that AmfR and AmfBA are essential for extracellular AmfS activity. The same experiment showed that an adpA mutant (18) also lacked the extracellular activity, suggesting that regulation by AmfS is under the control of A-factor (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Extracellular complementation of the aerial-mycelium deficiency in the amfS mutant. Each donor strain (upper colonies) was inoculated in close proximity to the amfS mutant (lower colonies) on YMP-glucose agar medium, and patches were photographed after 5 days of growth at 28°C. WT, wild type.

Since AmfR is a response regulator of a two-component regulatory system, it is most likely that it regulates transcription of amfS. However, we previously observed that an amfR mutant produced streptomycin at the wild-type level (24), which contradicts the streptomycin-negative phenotype of the amfS mutant. If amfR is essential for the transcription of amfS, the amfR mutant should be as defective in both aerial-mycelium formation and streptomycin production as the amfS mutant. There is at present no explanation for the inconsistency. On the other hand, the AmfBA products are probably involved in the export of AmfS or its derivative. The wild-type morphology of the amfBA mutant may be caused by AmfS accumulated intracellularly. The intracellular AmfS could be converted to a putative active form, which is suggested below, by some mechanism that occurs independently of its secretion. Otherwise, the wild-type phenotype of the amfBA mutant could be caused by a very reduced but sufficient level of extracellular AmfS secreted via an alternative transport mechanism. We need more precise analyses to show whether AmfBA is directly involved in secretion of AmfS.

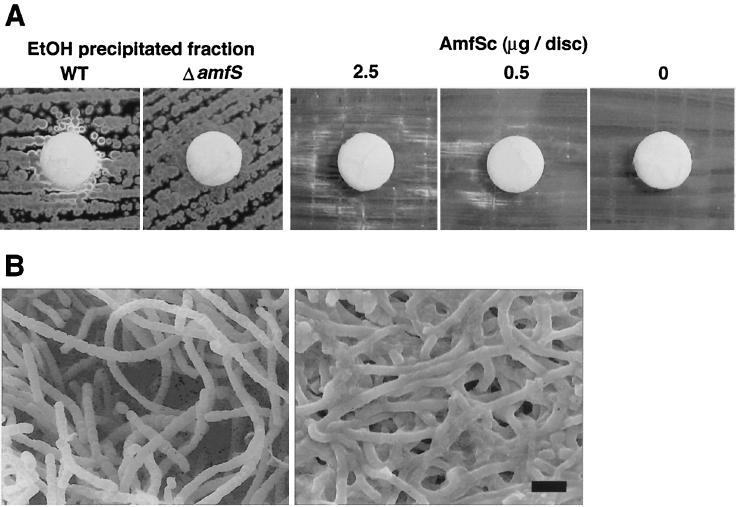

To further characterize the above-mentioned extracellular activity, the culture supernatant of the wild-type strain was examined. The S. griseus wild-type strain was cultured in 1 liter of YMP-glucose liquid medium for 2 days at 28°C, and 2 volumes of ethanol was added to the culture supernatant. The mixture was incubated for 2 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min. The resultant precipitate was dissolved in 1× TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.0]) to obtain a solution containing approximately 3 mg of protein/ml. Fifty microliters of the solution was then used to saturate a filter disk, which was subsequently placed onto a YMP-glucose agar plate inoculated with the amfS mutant to form a confluent lawn. After incubation at 28°C, the ethanol-precipitated fraction of the wild-type strain diffusing from the disk restored aerial mycelia in the adjacent colonies of the amfS mutant (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the same fraction of the amfS mutant did not show aerial mycelium-inducing activity, suggesting that the effective substance contained in the wild-type fraction is the AmfS product or its derivative.

FIG. 4.

Stimulation of aerial-mycelium formation in the amfS mutant by the wild-type culture supernatant and synthetic C-terminal octapeptide of AmfS. (A) Disks were soaked with ethanol (EtOH)-precipitated fractions of the wild type (WT), the amfS mutant (ΔamfS), and the synthetic C-terminal octapeptide (AmfSc). The white colonies contrasting with the dark ones were producing aerial hyphae. Patches were photographed after 5 days of growth for the ethanol precipitate and after 7 days of growth for the synthetic peptide. (B) Scanning electron micrograph of the amfS mutant with (left) and without (right) induction by the synthetic octapeptide. The AmfSc-treated colonies formed abundant aerial mycelia, most of which differentiated into spore chains via septum formation. In contrast, the untreated mutant grew only substrate hyphae. The photographs were taken after 7 days of growth. Bar, 2 μm.

Synthetic AmfS peptides.

We next carried out the assay described above with chemically synthesized AmfS peptides. First, the full-size 42-aa peptide (from Ala-2 to Pro-43) was prepared by the solid-phase synthesis method (Sawady Technology, Inc.) and dissolved in 1× TE (pH 7.0) containing 1% Triton X-100 to obtain a 1-mg/ml stock solution. The solution was further incubated with various ratios of reduced and oxidized glutathione, with the expectation of obtaining a form with the correct intrachain disulfide bridge. These preparations were subsequently diluted (20 to 200 times) with 1× TE and applied to filter disks that were processed as described above. The result showed that 50 μg or less of the synthetic peptide did not induce aerial-mycelium formation in the amfS mutant (not shown). We then synthesized the C-terminal portion of AmfS containing the second hydrophobic repeat (35-LSVVLCTP-42) (Fig. 1B). We speculated that the hydrophobic units may be important for the activity and that the peptide containing a single Cys residue can avoid an unwanted intramolecular disulfide bonding. As shown in Fig. 4, the synthetic octapeptide caused stimulation of aerial mycelium in the amfS mutant in a dose-dependent manner. Abundant aerial mycelium occasionally culminating in formation of spore chains was clearly observed by scanning electron microscopy. The minimum effective amount of the synthetic C-terminal peptide on a filter disk was 0.3 μg (0.36 nmol). Although the activity of the octapeptide was reproducible, it was irregularly dispersed from the disks, and the aerial-mycelium formation was delayed by approximately 2 days, appearing at 7 days, while aerial-mycelium formation with the ethanol precipitate of the wild-type culture broth was visible in 5 days. These results suggest that the octapeptide is not identical but mimetic to the actual active form of AmfS and that the peptidic molecule derived from the AmfS product is an extracellular morphogen in S. griseus. It also could be that the active fraction collected from the wild-type culture contains a mixture of signals which are sufficient to cause the distinct induction of aerial-mycelium formation in the amfS mutant.

Involvement of extracellular peptides in procaryotic cellular development has been well characterized in B. subtilis. The oligopeptide permease encoded by the spo0K locus is essential for the onset of endospore formation in this organism and is known to be involved in global uptake of regulatory peptides (13, 21). These include PhrA, an inhibitor of the specific phosphatase (RapA) for Spo0A, which is produced as a propeptide of 44 aa and processed into a C-terminal hexapeptide to be active as an inhibitory molecule (20).

In S. coelicolor A3(2), the hydrophobic peptide SapB is known as an extracellular morphogen (16, 28). Although the precise structure of the peptide is unknown, the amino acid content for the whole 18 aa (28) is different from that of the AmfS homolog of S. coelicolor. While SapB is assumed to be an extracellular surfactant that reduces the surface tension of the substrate mycelium to allow protrusion of aerial hyphae (22), AmfS is assumed to function intracellularly, as suggested by the wild-type phenotype of the amfBA mutant. The presence of such an intracellular regulatory peptide has been implied by the study of bldK, which encodes an oligopeptide permease in S. coelicolor (16, 17). The involvement of AmfS not only in aerial-mycelium formation but also in antibiotic production implies its role as a pleiotropic signal molecule. We expect that future biochemical studies will reveal its intrinsic role in the regulation and function of AmfS in S. griseus.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DDBJ accession number of the sequence described in this paper is AB006206.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Nishiyama and H. Ikeda for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by the High-Tech Research Center Project of the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck, E., G. Ludwig, A. Auerswald, B. Reiss, and H. Shaller. 1982. Nucleotide sequence and exact localization of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene from transposon Tn5. Gene 19:327-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibb, M. J., P. R. Findlay, and M. W. Johnson. 1984. The relationship between base composition and codon usage in bacterial genes and its use for the simple and reliable identification of protein-coding sequences. Gene 30:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blight, M. A., and I. B. Holland. 1990. Structure and function of haemolysin B, P-glycoprotein and other members of a novel family of membrane translocators. Mol. Microbiol. 4:873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chater, K. F. 1989. Sporulation in Streptomyces, p. 277-299. In I. Smith, R. A. Slepecky, and P. Setlow (ed.), Regulation of prokaryotic development: structural and functional analysis of bacterial sporulation and germination. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 5.Chater, K. F. 1993. Genetics of differentiation in Streptomyces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:685-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chater, K. F. 2000. Developmental decisions during sporulation in the aerial mycelium in Streptomyces, p. 33-48. In Y. V. Brun and L. J. Shimkets (ed.), Prokaryotic development. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Hanks, S. K., A. M. Quinn, and T. Hunter. 1988. The protein kinase family: conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domain. Science 241:42-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopwood, D. A., M. J. Bibb, K. F. Chater, T. Kieser, C. J. Bruton, H. M. Kieser, D. J. Lydiate, C. P. Smith, J. M. Ward, and H. Schrempf. 1985. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 9.Horinouchi, S., and T. Beppu. 1992. Autoregulatory factors and communication in actinomycetes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:377-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horinouchi, S., and T. Beppu. 1994. A-factor as a microbial hormone that controls cellular differentiation and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces griseus. Mol. Microbiol. 12:859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horinouchi, S., Y. Kumada, and T. Beppu. 1984. Unstable genetic determinant of A-factor biosynthesis in streptomycin-producing organisms: cloning and characterization. J. Bacteriol. 158:481-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keijer, B. J. F., G. P. Wezel. G. W. Canters, T. Kieser, and E. Vijgenboom. 2001. The ram-dependence of Streptomyces lividans differentiation is bypassed by copper. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:565-574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazazzera, B. A., J. M. Solomon, and A. D. Grossman. 1997. An exported peptide functions intracellularly to contribute cell density signaling in B. subtilis. Cell 899:917-925. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ma, H., and K. Kendall. 1994. Cloning and analysis of a gene cluster from Streptomyces coelicolor that causes accelerated aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 176:3800-3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Nodwell, J. R., K. McGovern, and R. Losick. 1996. An oligopeptide permease responsible for the import of an extracellular signal governing aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 22:881-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nodwell, J. R., and R. Losick. 1998. Purification of an extracellular signaling molecule involved in production of aerial mycelium by Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 180:1334-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohnishi, Y., S. Kameyama, H. Onaka, and S. Horinouchi. 1999. The A-factor regulatory cascade leading to streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus: identification of a target gene of the A-factor receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 34:102-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onaka, H., N. Ando, T. Nihira, Y. Yamada, T. Beppu, and S. Horinouchi. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the A-factor receptor gene from Streptomyces griseus. J. Bacteriol. 177:6083-6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perego, M., P. Glaser, and J. A. Hoch. 1996. Aspartyl-phosphate phosphatases deactivate the response regulator components of the sporulation signal transduction system in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1151-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perego, M., C. F. Higgins, S. R. Pearce, M. P. Gallagher, and J. A. Hoch. 1991. The oligopeptide transport system of Bacillus subtilis plays a role in the initiation of sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 5:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tillotson, R. D., H. A. B. Wösten, M. Richiter, and J. M. Willey. 1998. A surface active protein involved in aerial hyphae formation in the filamentous fungus Schizophillum commune restores the capacity of a bald mutant of the filamentous bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor to erect aerial structures. Mol. Microbiol. 30:595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda, K., K. Miyake, S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1993. A gene cluster involved in aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces griseus encodes proteins similar to the response regulator and membrane translocator. J. Bacteriol. 175:2006-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueda, K., C.-W. Hsheh, T. Tosaki, H. Shinkawa, T. Beppu, and S. Horinouchi. 1998. Characterization of an A-factor-responsive repressor for amfR essential for onset of aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces griseus. J. Bacteriol. 180:5085-5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vujaklija, D., S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1993. Detection of an A-factor-responsive protein that binds to the upstream activation sequence of strR, a regulatory gene for streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus. J. Bacteriol. 175:2652-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vujaklija, D., K. Ueda, S.-K. Hong, T. Beppu, and S. Horinouchi. 1991. Identification of an A-factor-dependent promoter in the streptomycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces griseus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 229:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward, J. M., G. R. Janssen, T. Kieser, M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, and M. J. Bibb. 1986. Construction and characterization of a series of multi-copy promoter-probe plasmid vectors for Streptomyces using the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene from Tn5 as indicator. Mol. Gen. Genet. 203:468-478. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Willey, J., R. Santamaria, J. Guijarro, M. Geistlich, and R. Losick. 1991. Extracellular complementation of a developmental mutation implicates a small sporulation protein in aerial mycelium formation by S. coelicolor. Cell 65:641-650. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Yamazaki, H., Y. Ohnishi, and S. Horinouchi. 2000. An A-factor-dependent extracytoplasmic function sigma factor (σAdsA) that is essential for morphological development in Streptomyces griseus. J. Bacteriol. 182:4596-4605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]