Abstract

Bacterial periplasmic nitrate reductases (Nap) can play different physiological roles and are expressed under different conditions depending on the organism. Rhodobacter sphaeroides DSM158 has a Nap system, encoded by the napKEFDABC gene cluster, but nitrite formed is not further reduced because this strain lacks nitrite reductase. Nap activity increases in the presence of nitrate and oxygen but is unaffected by ammonium. Reverse transcription-PCR and Northern blots demonstrated that the napKEFDABC genes constitute an operon transcribed as a single 5.5-kb product. Northern blots and nap-lacZ fusions revealed that nap expression is threefold higher under aerobic conditions but is regulated by neither nitrate nor ammonium, although it is weakly induced by nitrite. On the other hand, nitrate but not nitrite causes a rapid enzyme activation, explaining the higher Nap activity found in nitrate-grown cells. Translational nap′-′lacZ fusions reveal that the napK and napD genes are not efficiently translated, probably due to mRNA secondary structures occluding the translation initiation sites of these genes. Neither butyrate nor caproate increases nap expression, although cells growing phototrophically on these reduced substrates show a very high Nap activity in vivo (nitrite accumulation is sevenfold higher than in medium with malate). Phototrophic growth on butyrate or caproate medium is severely reduced in the NapA− mutants. Taken together, these results indicate that nitrate reduction in R. sphaeroides is mainly regulated at the level of enzyme activity by both nitrate and electron supply and confirm that the Nap system is involved in redox balancing using nitrate as an ancillary oxidant to dissipate excess reductant.

Three different types of bacterial nitrate-reducing systems have been described (reviewed in reference 24): cytoplasmic assimilatory nitrate reductases (Nas), membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductases (Nar), and periplasmic dissimilatory nitrate reductases (Nap). Nap systems have been identified and studied at the biochemical and/or genetic level in many gram-negative bacteria (5, 8, 11, 12, 26, 28, 29, 38). Nap enzymes are heterodimers consisting of a large 90-kDa catalytic subunit (NapA), containing a molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide cofactor and one [4Fe4S] center, and a small 13- to 19-kDa diheme cytochrome c (NapB). A 25-kDa membrane-bound cytochrome c (NapC) is involved in electron transfer from the quinol pool in the cytoplasmic membrane to the periplasmic NapAB soluble complex, and a cytoplasmic protein (NapD) seems to be necessary for the maturation of NapA (24, 26).

The crystal structure of the NapA protein of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans (9) and purification and characterization of the soluble domain of NapC from Paracoccus pantotrophus (33) and the Haemophilus influenzae NapB protein (6) have recently been described. Other nap genes are also present in some bacteria: napF, napG, and napH code for different iron-sulfur proteins, and napE and napK encode integral transmembrane proteins with unknown functions (26, 29). In the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the Nap system is encoded by the napKEFDABC gene cluster (28, 29).

Different physiological functions have been proposed for the bacterial Nap systems, including a role in redox balancing to dissipate excess reducing power under certain metabolic conditions (30-32, 36, 37), in denitrification (3, 4, 17), in adaptation to anaerobic growth (38), and in scavenging nitrate in nitrate-limited environments (6, 27). According to this diversity of functions for periplasmic nitrate reduction, there are some differences in nap gene expression depending on the organism, although Nap activity is usually present under aerobic conditions and is unaffected by ammonium (24). In Escherichia coli, Nap is maximally expressed at low nitrate concentrations under anaerobic conditions, and both Fnr and NarP are required for nap gene expression (8, 12, 26, 42). On the other hand, the Nap system from Ralstonia eutropha is maximally expressed under aerobic conditions at the stationary phase of growth and is not induced by nitrate (38), and in Paracoccus pantotrophus, maximal nap expression is found in cells growing aerobically with butyrate, a highly reduced carbon source, even in the absence of nitrate (37). In the phototrophic bacterium R. sphaeroides DSM158, Nap activity is stimulated by nitrate, is not affected by ammonium or by the intracellular C/N balance, and is present under both oxia and anoxia, although activity is higher under aerobic conditions (10, 28).

In this study we examined the expression of the nap genes from R. sphaeroides DSM158 in response to nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions by using different transcriptional and translational nap-lacZ reporter gene fusions and by Northern blotting experiments. The possible effect of the oxidation state of the carbon source on nap gene expression was also investigated. In addition, in vivo and in vitro Nap activity was measured under these experimental conditions to test for possible regulation at the level of enzyme activity and to better understand the physiological role of the Nap system in R. sphaeroides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. R. sphaeroides strains were grown at 30°C on peptone-yeast extract (PY) plates or RCV medium supplemented with yeast extract (0.1 g liter−1) or with the Pfennig vitamin solution (14) under phototrophic (light-anaerobiosis) or heterotrophic (dark-aerobiosis) conditions, as previously described (20, 23). d,l-Malate (4 g liter−1) and l-glutamate (1 g liter−1) were routinely used as the carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively, and when necessary, media with the indicated concentrations of alternative carbon substrates (butyrate or caproate) or nitrogen compounds (KNO3, KNO2, or NH4Cl) were also used. Escherichia coli strains were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani liquid or solid medium at 37°C (34).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| R. sphaeroides DSM158 | Wild type, Nap+ | 14, 23 |

| R. sphaeroides DSM158S | Spontaneous Smr mutant of strain DSM158, Nap+ | 23 |

| R. sphaeroides FR22Gm1 | Nonpolar napA::Gmr insertion mutant, Nap− | 28, 29 |

| R. sphaeroides FR22Gm2 | Polar napA::Gmr insertion mutant, Nap− | 28, 29 |

| E. coli S17-1 | Tra+, host for mobilizable plasmids | 39 |

| E. coli DH5α | Lac−, host for pSVB, pUC, and pBluescript plasmids | 34 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK+/KS+ | Apr, lacZ′, f1ori, T7 promoter | Stratagene |

| pUC plasmids | Apr, Lac+ | 41 |

| pSVB plasmids | Apr, Lac+ | 2 |

| pSUP401 | Apr, Cmr, Mob+ | 39 |

| pPHU234/235/236 | Tcr, lacZ | 13 |

| pML5B+ | Tcr, lacZ | 16 |

| pALTER-1 | Apr Tcr, lacZ′, f1ori, T7 promoter | Promega |

| pK18 | Kmr, lacZ | 15 |

| pFR10 | 6.8-kb PstI fragment (napKEFDABC) into pSVB20, Apr | 28 |

| pFR24 | 2.2-kb PstI-BamHI fragment from pFR10 into pUC8ΔSalI, Apr | 29 |

| pMGAC.I | 2.2-kb PstI-BamHI fragment from pFR24 into pBluescript, Apr | This work |

| pMGAC.II | 1.4-kb SalI-BamHI fragment from pFR10 into pSUP401, Cmr | This work |

| pMGAAtp | napA-lacZ transcriptional gene fusion | This work |

| pMGAK | napK21′-′lacZ translational gene fusion | This work |

| pMGAF | napF27′-′lacZ translational gene fusion | This work |

| pMGAD | napD9′-′lacZ translational gene fusion | This work |

| pMGAA | napA41′-′lacZ translational gene fusion | This work |

Analytical determinations and enzyme assays.

Cell growth was followed turbidimetrically by measuring the absorbance of the cultures at 680 nm. Nitrite in the medium was determined colorimetrically (40) as previously described (7). Protein was estimated according to Lowry et al. (18) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Nitrate reductase activity was assayed in whole cells or cell extracts, measuring the nitrite produced in the reaction with reduced methyl viologen (MV) as the artificial electron donor (20, 23). β-Galactosidase activity was determined at 30°C as described previously (22), and activities are expressed in arbitrary units (19). The data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments yielding essentially the same results, with standard deviations lower than 15%.

DNA and RNA methods.

Routine DNA manipulations (DNA isolation, restriction enzyme analysis, agarose gel electrophoresis, cloning procedures, and PCR amplifications) were performed using standard methods (34). Total RNA was isolated from R. sphaeroides cells by the hot phenol method as previously described (29). Northern blots and hybridization experiments were carried out with the nonradioactive digoxigenin kit from Boehringer-Mannheim using standard protocols (34). Reverse transcription amplification reactions (RT-PCR) were performed using the rTth DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer) in the presence of Mn2+ (25). The primers used were 1F (5′-CTTGTCGGGGTGCCGATTGGCA-3′), 1R (5′-CGGTCTGAACGTTTCCTGCGG-3′), 2F (5′-GGTACATGAGCAATCACGTTCT-3′), 2R (5′-CATGTCGGCCTCGCGCGTCCAG-3′), 3F (5′-GTGAAGTTGCCGCGGCGGGCGA-3′), 3R (5′-GAAGGTCGACAGGACCGCCAC G-3′), 4F (5′-CGCACGCGGCTCGAGACCCGAG-3′), 4R (5′-CCTCGAGGGCCGTGT TGAACCC-3′), and 5F (5′-CCGAATGCAGCTTTTGCGGTGC-3′).

Construction of lacZ transcriptional and translational fusions.

The transcriptional napA-lacZ gene fusion was constructed by cloning the 1.4-kb SalI-BamHI fragment of the napA gene from plasmid pFR10 into the mobilizable plasmid pSUP401 previously digested with XhoI and BamHI, to yield plasmid pMGAC.II. A BamHI fragment from plasmid pML5B+, which includes the lacZ gene without a promoter and the tetracycline resistance gene (16), was inserted into the BamHI site of pMGAC.II to give the final construction, pMGAAtp.

To create the translational napK′-′lacZ fusion, the 2.2-kb PstI-BamHI fragment of pFR24 was inserted into pBluescript to generate plasmid pMGAC.I. The 1.0-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment of this plasmid was then inserted into plasmid pPHU234 digested with EcoRI and XhoI. The resulting construct was linearized with BamHI, the ends were filled in with Klenow polymerase in the presence of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), DNA was digested with ScaI, and finally, the resulting blunt ends were ligated to yield plasmid pMGAK. This procedure fused codon 21 of napK in the appropriate reading frame to the lacZ gene. Negative controls with out-of-frame gene fusions were also constructed using plasmids pPHU235 and pPHU236.

To generate the translational napF′-′lacZ fusion, an XhoI site was created in the napF gene. For this purpose, the 2.2-kb PstI-BamHI fragment of pFR24 was inserted into pALTER-1, and the resulting plasmid was used for PCR amplification of a 1.25-kb XhoI fragment containing the 3′ end of the yntC gene, the nap promoter, the napK and napE genes, and the 5′ end of the napF gene (29). The primer pairs used were 5′-CCACGCACTTTGCCTCGAGATC-3′ and 5′-TGTCGGCCTCGAGCGTCCAGGGC-3′ (in boldface is shown the C→A mutation for creating the XhoI site, shown in italics). This PCR fragment was digested with XhoI, cloned into SalI-linearized pUC18 vector, and recovered as an EcoRI-PstI fragment for cloning into pPHU234 to give the final construction pMGAF, carrying an in-frame fusion between napF at codon 27 and lacZ. Similar procedures using plasmids pPHU235 and pPHU236 allowed the construction of out-of-frame fusions as negative controls.

The translational napD′-′lacZ fusion was constructed by inserting the 1.7-kb XhoI fragment of pFR24 into vector pK18. From the resulting plasmid, an EcoRI-HindIII fragment was then cloned into pPHU234 to give the final construction pMGAD, with codon 9 of napD fused in-frame to the lacZ gene. Negative controls with out-of-frame fusions were also generated using plasmids pPHU235 and pPHU236.

Finally, the translational napA′-′lacZ fusion was obtained by cloning the 2.2-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pMGAC.I into plasmid pPHU234. The resulting construct was linearized with BamHI, and after filling in the ends with Klenow polymerase in the presence of the four dNTPs, DNA was digested with ScaI and the resulting blunt ends were ligated to give plasmid pMGAA. This fused codon 41 of napA in-frame to the lacZ gene. Negative controls were also constructed using plasmids pPHU235 and pPHU236 to obtain out-of-frame fusions.

In all cases, DNA was sequenced automatically (ABI 310, Perkin-Elmer) by the chain termination method (35) to confirm the intended constructions, which were finally mobilized from E. coli S17-1 into R. sphaeroides DSM158S by filter matings as described previously (21, 22).

RESULTS

In vivo nitrite production and in vitro MV-nitrate reductase activity in R. sphaeroides under different growth conditions.

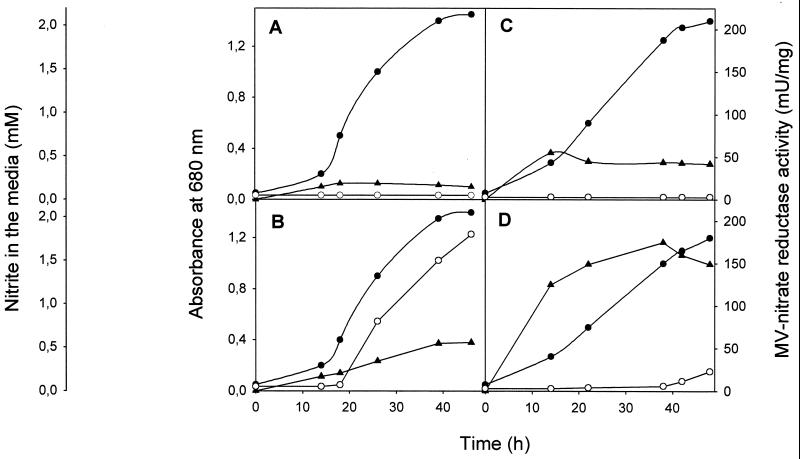

Cells of R. sphaeroides grown phototrophically under light-anaerobic conditions with malate as the carbon source showed MV-nitrate reductase activity in the absence of nitrate (Fig. 1A), and this activity increased about 3.5-fold in media with nitrate (Fig. 1B). Heterotrophic cultures under dark-aerobic conditions showed higher levels of MV-nitrate reductase activity (ca. 3-fold increase), and the activity was also stimulated by nitrate (Fig. 1C and D). However, nitrite accumulation in nitrate-containing media was very low under aerobic conditions, indicating that in vivo nitrate reduction takes place predominantly under anaerobic phototrophic conditions (Fig. 1B and D).

FIG. 1.

Time course of cell growth, MV-nitrate reductase activity, and nitrite accumulation in R. sphaeroides DSM158. Cells were grown phototrophically under light-anaerobic conditions (A and B) or heterotrophically under dark-aerobic conditions (C and D) in the presence of glutamate (A and C) or glutamate plus 10 mM KNO3 (B and D). Cell growth (•), MV-nitrate reductase activity (▴), and nitrite in the media (○) were measured as indicated in Materials and Methods.

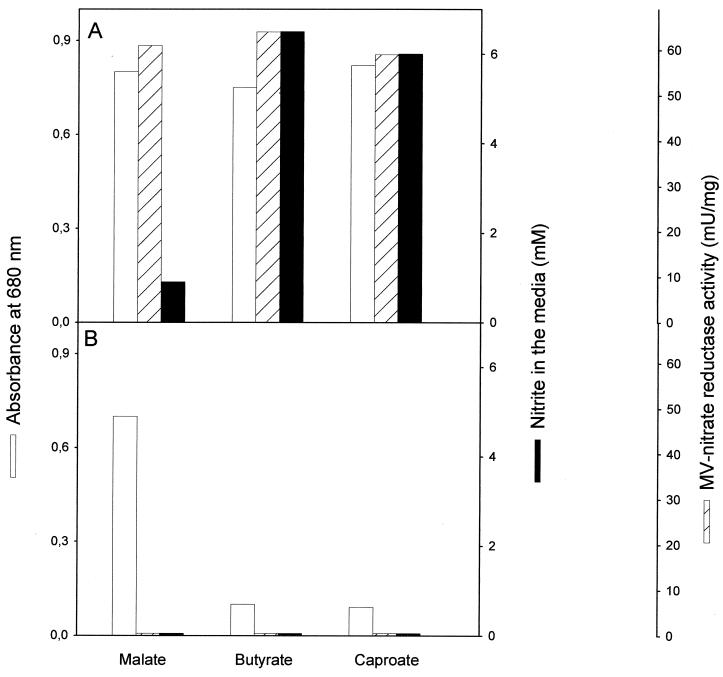

When R. sphaeroides was grown phototrophically on highly reduced carbon substrates, such as butyrate or caproate, the level of MV-nitrate reductase activity was similar than in media with malate, but nitrite accumulation was approximately 7-fold higher, reaching values as high as 6.5 mM (65% of total nitrate transformed to nitrite) in media with butyrate or caproate (Fig. 2A). Nitrite was not accumulated in the media when the cells were grown heterotrophically on butyrate or caproate (results not shown), again indicating that in vivo nitrate reduction is very low under aerobic conditions. In addition, R. sphaeroides mutant strains completely devoid of Nap activity, obtained by polar or nonpolar insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette into the napA gene (28, 29), were severely impaired in phototrophic growth on reduced carbon sources, although they grew well in media with malate (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Effect of carbon source on cell growth, MV-nitrate reductase activity, and nitrite accumulation in R. sphaeroides DSM158 (A) and the nonpolar NapA− insertion mutant FR22Gm1 (B). Cells were grown phototrophically with 30 mM malate, 30 mM butyrate, or 4 mM caproate as the sole carbon source and 5 mM NH4Cl plus 10 mM KNO3 as the nitrogen source. Cell growth, MV-nitrate reductase activity, and nitrite accumulation in the media were measured as indicated in Materials and Methods. Results with the polar NapA− insertion mutant FR22Gm2 were similar to those shown in B for the FR22Gm1 mutant.

Transcriptional analysis of the nap genes by RT-PCR and Northern blotting.

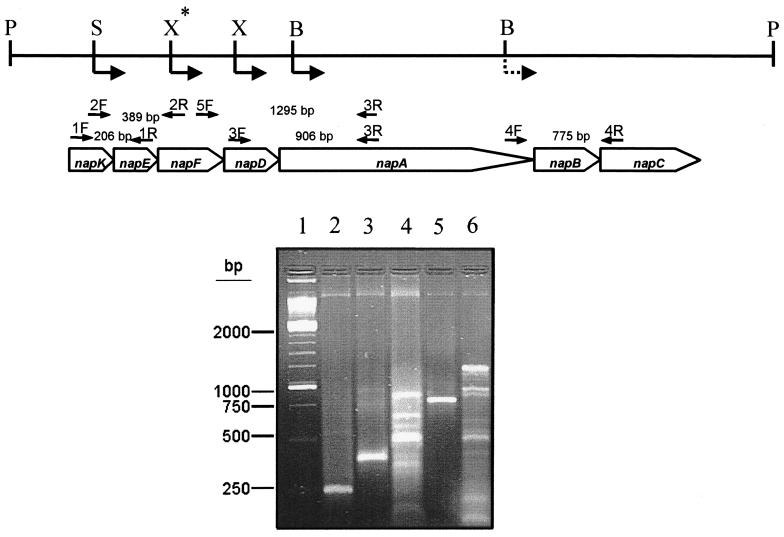

Previous analysis of different polar and nonpolar insertion mutants of R. sphaeroides suggested that the napKEFDABC genes are organized into a transcriptional unit. In addition, the napK transcription start site was identified by primer extension, and the same initiation point was found for cells grown aerobically or anaerobically with nitrate (29). To confirm that the nap genes are organized into an operon, we carried out RT-PCR analysis using several primer pairs which should amplify defined regions between two or three nap genes only if these genes are present in the same transcript. As shown in Fig. 3, all the amplification reactions yielded fragments of the expected sizes for each primer pair. In addition to the expected fragments of 906 or 1,295 bp, several shorter fragments were also amplified in the reactions with primer pairs 3F/3R and 5F/3R.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of nap gene expression by RT-PCR. The genetic organization of the R. sphaeroides nap genes, with the primer pairs used and the expected sizes of the RT-PCR products, is shown. Agarose gel electrophoresis of the products obtained in the amplification reactions is also shown. Lane 1, markers; lane 2, result of RT-PCR using primers 1F and 1R; lane 3, result of RT-PCR using primers 2F and 2R; lane 4, result of RT-PCR using primers 3F and 3R; lane 5, result of RT-PCR using primers 4F and 4R; lane 6, result of RT-PCR using the primers 5F and 3R. The restriction sites in the 6.8-kb PstI fragment used for the translational (normal arrows) and transcriptional (dashed arrow) nap-lacZ gene fusions are also indicated: B, BamHI; P, PstI; S, SalI; X, XhoI; and X*, XhoI site created by directed mutagenesis (see Materials and Methods).

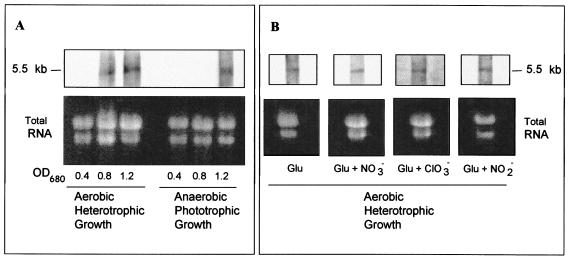

Northern blotting experiments allowed the identification of a single transcript of approximately 5.5 kb hybridizing with the 1-kb BstEII-BamHI fragment of the napA gene as a probe under all conditions tested (Fig. 4). The size of this transcript agrees with the whole size of the napKEFDABC gene cluster of R. sphaeroides. Expression of nap genes seemed to be slightly higher and was detected earlier in the growth phase under aerobic conditions than under anaerobic conditions. Thus, only a faint hybridization signal was observed in the phototrophic cultures with an absorbance at 680 nm of 0.8, whereas a very clear signal was found for the same absorbance value in the heterotrophic cultures (Fig. 4A). However, no significant differences were observed in transcript abundance when the cells were grown with nitrate, nitrite, or chlorate, a structural nitrate analog (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of R. sphaeroides nap transcription. Total RNA was separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with a napA-specific probe. (A) Total RNA was isolated from R. sphaeroides cells grown with malate and nitrate under aerobic heterotrophic or anaerobic phototrophic conditions when the cultures reached values absorbance at 680 nm of approximately 0.4, 0.8, or 1.2. (B) Total RNA was isolated from R. sphaeroides cells growing heterotrophically with malate as the carbon source and glutamate as the nitrogen source in the absence or presence of 10 mM KNO3, 10 mM KClO3, or 1 mM KNO2.

Analysis of nap gene expression by transcriptional and translational nap-lacZ gene fusions.

To determine if napK operon expression varies in response to different nitrate or nitrite concentrations and to study the possible regulation of nap gene expression in response to oxygen and different carbon sources, a transcriptional napA-lacZ reporter gene fusion was constructed. In addition, translational fusions between napK, napF, napD, or napA and the lacZ gene in the appropriate reading frame, and the corresponding negative controls with the genes fused out of frame, were also generated.

The R. sphaeroides strain containing the transcriptional napA-lacZ reporter gene fusion showed higher levels of β-galactosidase activity under aerobic conditions; a moderate but significant increase of about 3-fold in napA-lacZ expression was observed when the cells were grown heterotrophically compared to cells grown under anaerobic conditions (Table 2). It is worth noting that a similar increase of about 3-fold was observed in MV-nitrate reductase activity in the cells growing aerobically (Fig. 1). However, addition of nitrate, ammonium, nitrite, or chlorate had no significant effect on β-galactosidase activity under either aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Table 2), pointing out that the stimulatory effect of nitrate on MV-nitrate reductase activity (Fig. 1) is probably due to enzyme activation. These results are also in agreement with those of Northern blotting experiments (Fig. 4).

TABLE 2.

Expression of transcriptional napA-lacZ gene fusion in phototrophic and heterotrophic cultures of R. sphaeroides with different nitrogen sourcesa

| Addition | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic phototrophic cultures | Aerobic heterotrophic cultures | |

| None (control) | 65 | 190 |

| KNO3 | 70 | 210 |

| KNO3 + NH4Cl | 73 | 215 |

| NH4Cl | 67 | 200 |

| KNO3 | 88 | 205 |

| KClO3 | 65 | 185 |

The transcriptional napA-lacZ gene fusion was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in cells grown under anaerobic phototrophic or aerobic heterotrophic conditions in medium with malate as the carbon source and glutamate as the nitrogen source in the absence (control) or presence of KNO3, KNO3 plus NH4Cl, NH4Cl, KNO2, or KClO3. All these compounds were present at 10 mM except nitrite (1 mM).

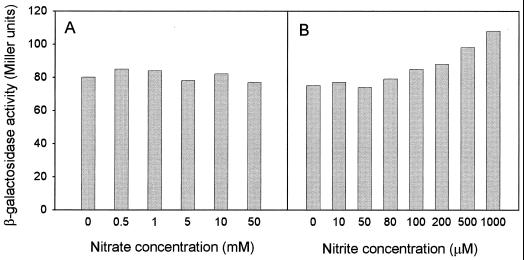

In E. coli, the napF operon is maximally expressed at 1 mM nitrate and expression is suppressed at nitrate concentrations higher than 5 mM (42). The effect of nitrate concentration on napA-lacZ expression was also tested in R. sphaeroides DSM158, and no significant differences in β-galactosidase activity were found in a range of 0 to 50 mM nitrate in cells grown phototrophically (Fig. 5A). However, a slight induction of napA-lacZ expression was observed in response to nitrite concentrations, and this modest effect was repeatedly seen in four independent experiments with cells grown phototrophically (Fig. 5B), although it was not observed in cells grown under aerobic heterotrophic conditions (not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effect of increasing amounts of nitrate or nitrite on napA-lacZ expression in R. sphaeroides cells grown phototrophically. The transcriptional napA-lacZ gene fusion was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in cells grown under anaerobic phototrophic conditions in media with malate and glutamate and the indicated KNO3 (A) or KNO2 (B) concentration.

Expression of the transcriptional napA-lacZ reporter gene fusion was also studied in R. sphaeroides cells grown phototrophically on different carbon sources. No significant differences in the levels of β-galactosidase activity were found when the cells were cultured on malate, an oxidized carbon substrate, or on butyrate or caproate, which are highly reduced carbon sources (results not shown). This result is also in agreement with the similar levels of MV-nitrate reductase activity observed in R. sphaeroides wild-type cells grown on malate, butyrate, or caproate (Fig. 2A). Therefore, although growth on highly reduced carbon sources increased the in vivo nitrate reductase activity (i.e., nitrite accumulation, Fig. 2A), this effect seems not to be due to nap transcription regulation.

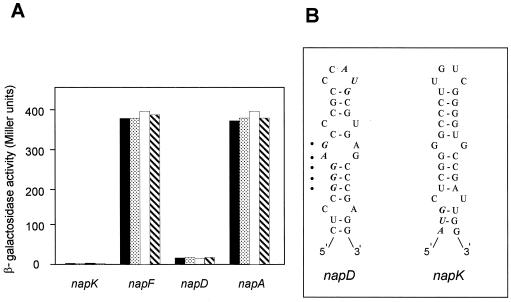

R. sphaeroides strains carrying translational napF′-′lacZ or napA′-′lacZ gene fusions showed β-galactosidase activity only when these nap genes and the reporter lacZ gene were fused in the same reading frame, and this activity was unaffected by nitrate, nitrite, or ammonium (Fig. 6A). However, the translational napK′-′lacZ and napD′-′lacZ gene fusions showed very low β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 6A), although DNA sequencing confirmed that the nap genes were fused to the lacZ gene in the correct reading frame. Computer analysis of the R. sphaeroides nap gene region using the Stemloop and FoldRNA programs of the Genetics Computer Group software package revealed that the napK and napD regions contain more putative mRNA secondary structures than other nap genes. In particular, a possible secondary structure occluding the ribosome-binding site and the translation initiation site of napD and a putative structure sequestering the AUG start codon of napK, a gene lacking a typical Shine-Dalgarno sequence, were found (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Expression of different translational nap′-′lacZ gene fusions and potential mRNA secondary structures involving the translation initiation sites of the napK and napD genes. (A) Translational fusions of the napK, napF, napD, and napA genes to the lacZ gene were created as described in Materials and Methods. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in R. sphaeroides cells grown under aerobic heterotrophic conditions in media with malate and glutamate in the absence (black bars) or presence of 10 mM KNO3 (stippled bars), 10 mM NH4Cl plus 10 mM KNO3 (white bars), or 1 mM KNO2 (hatched bars). (B) Putative mRNA secondary structures occluding the translation initiation sites of the napK and napD genes. The AUG start codons are indicated in boldface and italics, and the ribosome-binding site of napD is also marked by black dots.

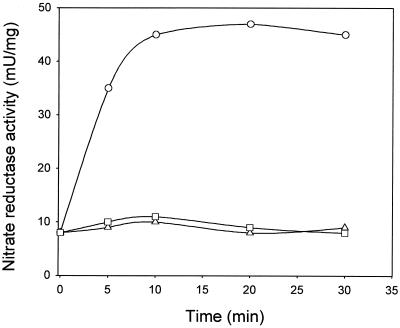

Short-term activation of MV-nitrate reductase by nitrate.

Northern blots (Fig. 4) and β-galactosidase activity results (Table 2, Fig. 5 and 6) suggest that nitrate is not an inducer of nap gene expression in R. sphaeroides and its stimulatory effect on nitrate reductase activity can be due to enzyme activation. To test this possibility, cells grown phototrophically in absence of nitrate were assayed for MV-nitrate reductase activity after 10 mM nitrate addition. As shown in Fig. 7, rapid activation of the enzyme was observed in the presence of nitrate, reaching maximal activity 10 min after nitrate addition. It is worth noting that this short-term stimulation of MV-nitrate reductase activity by nitrate is similar (about 4-fold increase) to that observed in cells grown in nitrate-containing media compared to cultures grown in the absence of nitrate (Fig. 1). On the contrary, this short-term activation of nitrate reductase was not observed when 1 mM nitrite was added (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Effect of nitrate on MV-nitrate reductase activity in R. sphaeroides DSM158. Cells were grown phototrophically with malate as the carbon source and glutamate as the sole nitrogen source. At time zero, cells were collected, resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and distributed among three flasks; one of them was used as a control (□), and 10 mM KNO3 (○) or 1 mM KNO2 (▵) was added to the others. At the indicated times, samples were collected and washed twice in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the MV-nitrate reductase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

The phototrophic bacterium R. sphaeroides DSM158 has a Nap system, encoded by the napKEFDABC gene cluster (28, 29), although this strain is devoid of nitrite reductase and the nitrite formed in the reaction is accumulated in the culture medium. Thus, nitrite accumulation is a valuable indicator of in vivo Nap activity, which depends on the electron supply from the membrane quinol pool to the periplasmic NapAB complex via the NapC cytochrome. On the other hand, the in vitro Nap activity assayed with reduced MV as an artificial electron donor is a measure of the total activity, independent of NapC and the redox state of the quinol pool, even when the Nap system is not being used by the cells due to the absence of an electron supply. In earlier studies, it was observed that MV-Nap activity in R. sphaeroides is higher under heterotrophic aerobic than under phototrophic anaerobic conditions and that the activity is stimulated by nitrate but unaffected by ammonium or the C/N balance (10, 28). However, a detailed study on the regulation of Nap activity or nap gene expression under different conditions has not been performed.

R. sphaeroides Nap system is involved in redox balancing.

We have previously proposed that the R. sphaeroides Nap system is involved in the maintenance of the cellular redox balance because nitrate and chlorate, which are not used by assimilatory or respiratory pathways, stimulate phototrophic growth in the wild-type strain but not in a Nap− transposon Tn 5 insertion mutant (23, 32). However, it could be argued that the high MV-Nap activity in the aerobic heterotrophic cultures (28) does not favor this hypothesis. Here we show that, although the Nap activity assayed in vitro with MV was higher in cells grown heterotrophically with nitrate, the Nap activity in vivo was very low under these aerobic conditions because nitrite was only accumulated at significant concentrations in the anaerobic phototrophic cultures (Fig. 1). Nitrite accumulation in phototrophic cultures with butyrate or caproate was 7-fold higher than in media with malate, although there were no significant differences in the MV-Nap activity in vitro (Fig. 2A), thus revealing that in vivo Nap activity is higher in cells growing on reduced carbon sources.

As the assimilation of these reduced carbon substrates generates more reducing equivalents than assimilation of oxidized carbon sources, the high nitrite accumulation in media with butyrate or caproate is a consequence of increased electron flow to the Nap enzyme under these conditions. On the other hand, nitrite production by cells growing aerobically was very low in media with malate (Fig. 1D) and in butyrate- or caproate-containing media (not shown), probably because electrons are preferentially directed to oxygen. In addition, phototrophic growth on butyrate or caproate was drastically weakened in both polar and nonpolar NapA− insertion mutants, which were able to grow well on malate (Fig. 2B). These results confirm that the Nap system of R. sphaeroides dissipates excess reductant to allow an optimal cellular redox balance and point out that electron supply is a key factor regulating Nap activity in vivo.

In vivo Nap activity but not nap gene expression increases on highly reduced carbon sources.

It has recently been described that nap transcription is induced in P. pantotrophus cells growing aerobically on butyrate. In this organism, two transcription start sites separated by 7 bp have been identified, the use of which is determined by the oxidation state of the carbon source (37). In R. sphaeroides, the same transcription initiation site was found for cells growing aerobically or anaerobically (29), and no significant differences in MV-Nap activity were observed in cells growing phototrophically on malate, butyrate, or caproate (Fig. 2A). In addition, expression of the transcriptional napA-lacZ gene fusion was similar in the cells grown with malate, butyrate, or caproate, indicating that the oxidation state of the carbon source does not regulate nap gene expression in R. sphaeroides. However, as discussed above, in vivo Nap activity was higher in cells growing phototrophically on reduced carbon sources, as revealed by the high nitrite accumulation in media with butyrate or caproate (Fig. 2A). Thus, the oxidation state of the carbon source affects the in vivo Nap activity, which depends on the electron supply.

R. sphaeroides nap genes are cotranscribed, yielding a 5.5-kb product.

We have previously suggested by using polar and nonpolar insertion mutants of R. sphaeroides that the napKEFDABC genes are organized into an operon (29). Primer extension analysis revealed that the R. sphaeroides nap transcript initiates 51 nucleotides upstream from the napK translation start codon under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, and a σ70 promoter was also identified upstream from the transcriptional start site (29). In this study, RT-PCR analysis confirms that the napKEFDABC genes are cotranscribed, because DNA fragments of the expected sizes were amplified using primer pairs corresponding to different nap genes, which indicates that these genes are present in the same transcript (Fig. 3). In addition, only one transcript of about 5.5 kb, which is in agreement with the size of the whole napKEFDABC gene region, was detected in Northern blots (Fig. 4), also demonstrating that the R. sphaeroides nap genes are organized into a transcriptional unit.

Nitrate is not an inducer of nap gene expression but activates nitrate reductase.

Analysis of nap transcription by Northern blots (Fig. 4B) and nap-lacZ reporter gene fusions (Table 2) clearly indicates that neither nitrate nor its structural analog chlorate activates nap gene expression in R. sphaeroides. In E. coli, napF operon transcription is induced at low nitrate concentrations (1 mM), although expression is suppressed under high-nitrate conditions (more than 5 mM), and nitrite has only a minor regulatory effect (42). In R. sphaeroides, nitrate failed to increase napA-lacZ expression at all concentrations tested between 0 and 50 mM (Fig. 5A), indicating that stimulation of nitrate reductase activity by nitrate (Fig. 1) takes place at a posttranscriptional level. Support for this idea also comes from the short-term activation of the nitrate reductase in the presence of nitrate (Fig. 7). Therefore, nitrate is an activator of the enzyme but not an inducer of nap gene expression. On the contrary, nitrite does not activate the enzyme (Fig. 7) but slightly increases napA-lacZ expression under anaerobic phototrophic growth conditions (Fig. 5B). It is possible that nitrite is not a significant inducer of R. sphaeroides nap gene expression, and its modest effect could reflect an ancient role of this molecule as a regulator of nap gene expression. In addition, ammonium has no effect on nap gene expression (Table 2, Fig. 6), confirming previous observations (10, 28).

nap gene expression but not in vivo Nap activity increases under aerobic conditions.

Northern blotting experiments revealed that nap expression is higher under aerobic conditions than in anaerobically grown cells and that the nap transcript is detected earlier in cells growing aerobically (Fig. 4A). In addition, the β-galactosidase activity of the R. sphaeroides cells carrying the transcriptional napA-lacZ gene fusion is about 3-fold higher under aerobic conditions than under anoxia (Table 2), which correlates with the increase in in vitro MV-nitrate reductase activity under aerobic conditions (Fig. 1). However, as mentioned above, in vivo Nap activity is clearly reduced under aerobic conditions, as indicated by the low nitrite accumulation in the heterotrophic cultures. This can be due to a low electron supply to the NapAB complex when electrons are preferentially directed to the aerobic respiratory electron transport chain.

This pattern of regulation by oxygen is different in E. coli, in which nap gene expression only takes place in anaerobiosis and transcription is activated synergistically by Fnr and NarP (8), and in P. pantotrophus, in which nap transcription is restricted to aerobic growth, being negatively regulated in anaerobiosis (37). However, regulation of the R. sphaeroides Nap system is similar to that in Ralstonia eutropha, in which the Nap system is maximally expressed at the stationary phase of aerobic cultures and is not induced by nitrate (38).

mRNA secondary structures may affect the translation of napK and napD genes.

R. sphaeroides cells carrying translational napF′-′lacZ and napA′-′lacZ fusions showed similar β-galactosidase activities in media with glutamate, nitrate, nitrite, or ammonium, confirming that nap expression is not affected by the nitrogen source. However, β-galactosidase activity was almost undetectable in cells carrying translational napK′-′lacZ and napD′-′lacZ fusions (Fig. 6A), suggesting that these genes are not translated efficiently. Sequence analysis of these genes revealed the presence of a putative mRNA secondary structure occluding the ribosome-binding site and the translation initiation site of napD and the AUG start codon of napK, which lacks a typical Shine-Dalgarno sequence (Fig. 6B).

We suggest that these mRNA structures may play a key role in regulating the expression of the napK and napD genes, blocking translation initiation or affecting translational coupling, as proposed for similar structures present in some photosynthetic genes from Rhodobacter capsulatus (1). The presence of mRNA secondary structures in the napD gene region could also explain the existence of additional fragments shorter than 906 and 1,295 bp in the RT-PCR amplification reactions with primer pairs 3F/3R and 5F/3R, which cover the napDA and the napFDA regions, respectively (Fig. 3).

Regulation and function of the Nap system vary depending on the organism.

Taken together, the results of this work indicate that the R. sphaeroides Nap system plays a role in redox balancing and that its regulation takes place mainly at the posttranscriptional level. The presence of nitrate and an appropriate electron supply from the quinol pool to the periplasmic NapAB complex, as occurs under anaerobic growth conditions on highly reduced carbon sources, are the most important factors controlling nitrate reductase activity in vivo. However, the Nap systems are present in a wide range of bacteria (11), and nap gene expression seems to be regulated differently in response to oxygen, nitrate, and carbon substrates (8, 36-38, 42), and even some Nap proteins present different biochemical properties (6), depending on the organism. These facts can reflect the versatility of the Nap systems for playing distinct physiological functions in different bacteria, or even in the same organism under different metabolic conditions. Therefore, bacteria expressing periplasmic nitrate reductase could have a selective advantage in competition with strains lacking this system during nitrate-limited growth (6, 27, 42) or, in particular for R. sphaeroides, during metabolic conditions generating excess reductant, such as phototrophic growth on reduced carbon substrates.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Klipp (University of Bochum, Germany) for providing strains and plasmids.

We also acknowledge the financial support of DGESIC (grant PB98 1022 CO2 01) and Junta de Andalucia (CVI 0117), Spain, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany. M.G. was the recipient of a fellowship from the University of Cordoba, and M.D.R. holds a postdoctoral contract from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti, M., D. H. Burke, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Structure and sequence of the photosynthesis gene cluster, p.1083-1106. In R. E. Blankenship, M. T. Madigan, and C. E. Bauer (ed.), Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 2.Arnold, W., and A. Pühler. 1988. A family of high-copy-number plasmid vectors with single end-label sites for rapid nucleotide sequencing. Gene 70:171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedzyk, L., T. Wang, and R. E. Ye. 1999. The periplasmic nitrate reductase in Pseudomonas sp. strain G-179 catalyzes the first step of denitrification. J. Bacteriol. 181:2802-2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, L. C., D. J. Richardson, and S. J. Ferguson. 1990. Periplasmic and membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductases in Thiosphaera pantotropha. The periplasmic enzyme catalyzes the first step in aerobic denitrification. FEBS Lett. 265:85-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berks, B. C., D. J. Richardson, A. Reilly, A. C. Willis, and S. J. Ferguson. 1995. The napEDABC gene cluster encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase system of Thiosphaera pantotropha. Biochem. J. 309:983-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brigé, A., J. A. Cole, W. R. Hagen, Y. Guisez, and J. J. Van Beeumen. 2001. Overproduction, purification and novel redox properties of the dihaem cytochrome c, NapB, from Haemophilus influenzae. Biochem. J. 356:851-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caballero, F. J., C. Moreno-Vivián, F. Castillo, and J. Cárdenas. 1986. Nitrite uptake system in photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulata E1F1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 848:16-23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darwin, A. J., E. C. Ziegelhoffer, P. J. Kiley, and V. Stewart. 1998. Fnr, NarP, and NarL regulation of Escherichia coli K-12 napF (periplasmic nitrate reductase) operon transcription in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 180:4192-4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dias, J. M., M. E. Than, A. Humm, R. Huber, G. P. Bourenkov, H. D. Bartunik, S. Bursakov, J. Calvete, J. Caldeira, C. Carneiro, J. J. G. Moura, and I. Moura. 1999. Crystal structure of the first dissimilatory nitrate reductase at 1.9 Å solved by MAD methods. Structure 7:65-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobao, M. M., M. Martínez-Luque, C. Moreno-Vivián, and F. Castillo. 1994. Effect of carbon and nitrogen metabolism on nitrate reductase activity of Rhodobacter capsulatus E1F1. Can. J. Microbiol. 40:645-650. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanagan, D. A., L. G. Gregory, J. P. Carter, A. Karakas-Sen, D. J. Richardson, and S. Spiro. 1999. Detection of genes for periplasmic nitrate reductase in nitrate respiring bacteria and in community DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grove, J., S. Tanapongpipat, G. Thomas, L. Griffiths, H. Crooke, and J. Cole. 1996. Escherichia coli K-12 genes essential for the synthesis of c-type cytochromes and a third nitrate reductase located in the periplasm. Mol. Microbiol. 19:467-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hübner, P., J. C. Willison, P. M. Vignais, and T. A. Bickle. 1991. Expression of regulatory nif genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 173:2993-2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerber, N. L., and J. Cárdenas. 1982. Nitrate reductase from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 150:1091-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kutsche, M., S. Leimkühler, S. Angermüller, and W. Klipp. 1996. Promoters controlling expression of the alternative nitrogenase and the molybdenum uptake system in Rhodobacter capsulatus are activated by NtrC, independent of σ54, and repressed by molybdenum. J. Bacteriol. 178:2010-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labes, M., A. Pühler, and R. Simon. 1990. A new family of RSF1010-derived expression and lac-fusion broad-host-range vectors for Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 89:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, H. P., S. Takio, T. Satoh, and I. Yamamoto. 1999. Involvement in denitrification of the napKEFDABC genes encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase system in the denitrifying phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides f. sp. denitrificans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:530-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 20.Moreno-Vivián, C., J. Cárdenas, and F. Castillo. 1986. In vivo short-term regulation of nitrogenase by nitrate in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata E1F1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 34:105-109. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno-Vivián, C., M. Schmehl, B. Masepohl, W. Arnold, and W. Klipp. 1989. DNA sequence and genetic analysis of the Rhodobacter capsulatus nifENX gene region: homology between NifX and NifB suggests involvement of NifX in processing of the iron-molybdenum cofactor. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216:353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno-Vivián, C., S. Hennecke, A. Pühler, and W. Klipp. 1989. Open reading frame 5 (ORF5), encoding a ferredoxin-like protein, and nifQ are cotranscribed with nifE, nifN, nifX, and ORF4 in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 171:2591-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno-Vivián, C., M. D. Roldán, F. Reyes, and F. Castillo. 1994. Isolation and characterization of transposon Tn 5 mutants of Rhodobacter sphaeroides deficient in both nitrate and chlorate reduction. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 115:279-284. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno-Vivián, C., P. Cabello, M. Martínez-Luque, R. Blasco, and F. Castillo. 1999. Prokaryotic nitrate reduction: molecular properties and functional distinction among bacterial nitrate reductases. J. Bacteriol. 181:6573-6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers, T. W., and D. H. Gelfand. 1991. Reverse transcription and DNA amplification by a Thermus thermophilus DNA polymerase. Biochemistry 30:7661-7666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter, L. C., and J. A. Cole. 1999. Essential roles for the products of the napABCD genes, but not napFGH, in periplasmic nitrate reduction by Escherichia coli K-12. Biochem. J. 344:69-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potter, L. C., P. Millington, L. Griffiths, G. H. Thomas, and J. A. Cole. 1999. Competition between Escherichia coli strains expressing either a periplasmic or a membrane-bound nitrate reductase: does Nap confer a selective advantage during nitrate-limited growth? Biochem. J. 344:77-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reyes, F., M. D. Roldán, W. Klipp, F. Castillo, and C. Moreno-Vivián. 1996. Isolation of periplasmic nitrate reductase genes from Rhodobacter sphaeroides DSM158: structural and functional differences among prokaryotic nitrate reductases. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1307-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes, F., M. Gavira, F. Castillo, and C. Moreno-Vivián. 1998. Periplasmic nitrate-reducing system of the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides DSM158: transcriptional and mutational analysis of the napKEFDABC gene cluster. Biochem. J. 331:897-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson, D. J., and S. J. Ferguson. 1992. The influence of carbon substrate on the activity of the periplasmic nitrate reductase in aerobically grown Thiosphaera pantotropha. Arch. Microbiol. 157:535-537. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson, D. J., G. F. King, D. K. Kelly, A. G. McEwan, S. J. Ferguson, and J. B. Jackson. 1988. The role of auxiliary oxidants in maintaining redox balance during phototrophic growth of Rhodobacter capsulatus on propionate or butyrate. Arch. Microbiol. 150:131-137. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roldán, M. D., F. Reyes, C. Moreno-Vivián, and F. Castillo. 1994. Chlorate and nitrate reduction in the phototrophic bacteria Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Curr. Microbiol. 29:241-245. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roldán, M. D., H. J. Sears, M. R. Cheesman, S. J. Ferguson, A. J. Thomson, B. C. Berks, and D. J. Richardson. 1998. Spectroscopic characterization of a novel multiheme c-type cytochrome widely implicated in bacterial electron transport. J. Biol. Chem. 273:28785-28790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sears, H. J., S. Spiro, and D. J. Richardson. 1997. Effect of carbon substrate and aeration on nitrate reduction and expression of the periplasmic and membrane-bound nitrate reductases in carbon-limited continuous cultures of Paracoccus denitrificans Pd1222. Microbiology 143:3767-3774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sears, H. J., G. Sawers, B. C. Berks, S. J. Ferguson, and D. J. Richardson. 2000. Control of periplasmic nitrate reductase gene expression (napEDABC) from Paracoccus pantotrophus in response to oxygen and carbon substrates. Microbiology 146:2977-2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siddiqui, R. A., U. Warnecke-Eberz, A. Hengsberger, B. Schneider, S. Kostka, and B. Friedrich. 1993. Structure and function of a periplasmic nitrate reductase in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. J. Bacteriol. 175:5867-5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snell, F. D., and C. T. Snell. 1949. Colorimetric methods of analysis, 3rd ed., vol. 2, p. 804-805. D. van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, N.Y.

- 41.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, H., C. P. Tseng, and R. P. Gunsalus. 1999. The napF and narG nitrate reductase operons in Escherichia coli are differentially expressed in response to submicromolar concentrations of nitrate but not nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 181:5303-5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]