Abstract

Siderophore-mediated iron transport in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent upon the cytoplasmic membrane-associated TonB1 energy coupling protein for activity. To assess the functional significance of the various regions of this molecule and to identify functionally important residues, the tonB1 gene was subjected to site-directed mutagenesis, and the influence on iron acquisition was determined. The novel N-terminal extension of TonB1, which is absent in all other examples of TonB, was required for TonB1 activity in both P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. Appending it to the N terminus of the nonfunctional (in P. aeruginosa) Escherichia coli TonB protein (TonBEc) rendered TonBEc weakly active in P. aeruginosa and did not compromise the activity of this protein in E. coli. Elimination of the membrane-spanning, presumed membrane anchor sequence of TonB1 abrogated TonB1 activity in P. aeruginosa and E. coli. Interestingly, however, a conserved His residue within the membrane anchor sequence, shown to be required for TonBEc function in E. coli, was shown here to be essential for TonB1 activity in E. coli but not in P. aeruginosa. Several mutations within the C-terminal end of TonB1, within a region exhibiting the greatest similarity to other TonB proteins, compromised a TonB1 contribution to iron acquisition in both P. aeruginosa and E. coli, including substitutions at Tyr264, Glu274, Lys278, and Asp304. Mutations at Pro265, Gln293, and Val294 also impacted negatively on TonB1 function in E. coli but not in P. aeruginosa. The Asp304 mutation was suppressed by a second mutation at Glu274 of TonB1 but only in P. aeruginosa. Several TonB1-TonBEc chimeras were constructed, and assessment of their activities revealed that substitutions at the N or C terminus of TonB1 compromised its activity in P. aeruginosa, although chimeras possessing an E. coli C terminus were active in E. coli.

Energy-dependent receptor-mediated ligand uptake across the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria is dependent upon the function of the product of the tonB gene (5). This apparently dimeric (14) proline-rich protein is, in Escherichia coli, anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane via its N terminus and extends into the periplasm (23, 61, 62), where it interacts with receptor proteins in the outer membrane (6, 22, 26, 66, 68). This disposition of the protein reflects its apparent role in coupling the energized state of the cytoplasmic membrane to the outer membrane receptors (52). TonB interaction with receptors is promoted by ligand binding to these receptors (53, 54), suggesting that TonB is specifically recruited by ligand-loaded receptors. The ligand-loaded status is apparently reflected by changes in receptor conformation upon ligand binding (7, 19, 32, 46, 47, 48, 55), including a change in the N-terminal TonB box region (see below) implicated in TonB association (51).

Previous models of TonB-dependent receptors described them as gated porins whose activities were modulated by the action of the TonB protein (38, 63), although the recently determined crystal structures of two of these, FhuA (19, 47) and FepA (12), indicate that the channels are not gated. Rather, a cork domain formed by the N terminus plugs the channel from the periplasmic side (12, 19, 47). These receptors, which include receptors for ferric siderophores (10), vitamin B12 (33), heme and hemin (73), and transferrin (10, 21), show conserved regions of homology (50), one of which, the so-called TonB box (67), is proposed to interact directly with TonB (6, 26). Such interaction appears to be mediated by the C-terminal region of the TonB protein (31, 40) at or near residue Glu160 (6, 26). Indeed, a recent cross-linking study confirmed the interaction of TonB and the TonB box region of the TonB-dependent vitamin B12 receptor, BtuB, mediated by residues in TonB surrounding GlnQ160 (13). Still, derivatives of another TonB-dependent receptor, FhuA, lacking the TonB box and, indeed, most of the N-terminal cork domain, was still TonB dependent (8, 39) and could interact with TonB (29), indicating that TonB also interacts with its receptors via regions other than the TonB box.

Full TonB function is, in E. coli, dependent upon the products of the exbB and exbD genes (18, 24), which are localized in the cytoplasmic membrane (34, 35). The former is involved in the stabilization of TonB (1, 20, 37, 69), apparently via an interaction with the TonB N terminus (31, 36, 43, 72). ExbD also interacts with TonB (1) and ExbB (9, 20), apparently as part of a heterohexameric complex of ExbB and ExbD homotrimers (27). A recent model suggests that TonB shuttles between the outer and inner membranes, its association with the former dependent upon ExbBD and mediated by the TonB N terminus and its association with the latter mediated by its C terminus (45). This cycling between outer and inner membrane states is likely facilitated by conformational changes in TonB that occur in response to ExbB, the proton motive force, and the ligand-loaded receptor (42).

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore receptors show conserved regions of homology shared by members of the family of so-called TonB-dependent receptors (2, 15, 59), and a tonB gene has been identified in this organism (60). Although it displays significant homology, e.g., to E. coli TonB, this TonB protein is distinguished by the presence of additional sequences at its N terminus, making it larger than all other examples of TonB (60). Still, disruption of this gene abrogates siderophore-mediated iron uptake (60) and heme uptake (76), a finding consistent with an involvement in iron acquisition, as for other TonB proteins. Homologues of exbB and exbD have recently been described in P. aeruginosa, linked to a second tonB gene, tonB2, in an apparent operon structure (76). Despite the obvious iron regulation of this putative operon, however, inactivation of tonB2, exbB, or exbD had no adverse effect on iron or heme acquisition in this organism (76). In the present report we assess the functional importance of the novel N-terminal extension of the P. aeruginosa TonB protein (now called TonB1 [76]), as well as the conserved C terminus, and we show that the various mutations examined differentially affect TonB1 function in E. coli versus that in P. aeruginosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The iron-limited succinate minimal medium has been described previously (58), as has the iron-limited (deferrated) tryptic soy broth (DTSB) (57). When E. coli was cultivated, glucose (0.4% [wt/vol]) replaced succinate in this medium. Arginine-HCl (1 mM), methionine (1 mM), and thiamine (10 μM) were included in minimal media as needed. Luria broth base (L broth; Difco) was employed as rich medium throughout. Antibiotics (purchased from Sigma), including chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml, E. coli; 16 μg/ml, P. aeruginosa K1040), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and streptomycin (500 μg/ml), were included in the growth medium as appropriate. Bacteria were routinely cultured at 37°C, with shaking (200 rpm) in the case of broth cultures.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description and/or phenotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | endA hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR [φ80dlacΔ(lacZ) M15] | 4 |

| MM294 | supE448 rfbD1 spoT1 thi-1 endA1 hsdR17 pro | 65 |

| W3110 | Wild type | V. Braun, Universität Tübingen |

| KP1032 | W3110 tonB::Kan | 43 |

| RK5173 | F− Δ(argF-lac)U169 araD139 relA1 rpsL150 flb-5301 deoC1 thi gyrA219 non metE70 | 26 |

| RK5015 | RK5173 ΔtonB | R. Kadner, University of Virginia |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO6609 | met-9011 amiE200 rpsL pvd-9 | 28 |

| K1040 | PAO6609 ΔtonB::ΩHg | 75 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCG752 | pT7-5::tonBEc | 20 |

| pMMB206 | Broad-host-range, low-copy-number cloning vector; lacIq; Cmr | 56 |

| pQZ-TEC | pMMB206 derivative carrying tonBEc on a 1.7-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pCG752 | This study |

| pQZ-06 | pMMB206::tonB1 (wild type) | 75 |

| pQZ-A | pMMB206::tonB1 (Met1Leu) | This study |

| pQZ-CY | pMMB206::tonB1 (Cys36Gly) | This study |

| pQZ-H | pMMB206::tonB1 (His98Gly) | This study |

| pQZ-N1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (ΔSer33-Ile67) | This study |

| pQZ-N2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (ΔSer6-Pro83) | This study |

| pQZ-T | pMMB206::tonB1 (ΔPro82-Thr111) | This study |

| pQZ-C | pMMB206::tonB1 (ΔAsp260-Ala310) | This study |

| pQZ-Y1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Tyr264Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-Y2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Tyr264Phe) | This study |

| pQZ-P1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Pro265Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-P2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Pro265Gly) | This study |

| pQZ-Q1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Gln269Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-E1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Glu274Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-E2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Glu274Lys) | This study |

| pQZ-E3 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Glu274Ala/Asp304Asn) | This study |

| pQZ-K1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Lys278Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-K2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Lys278Glu) | This study |

| pQZ-R1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Arg288Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-R2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Arg288Glu) | This study |

| pQZ-Q2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Gln293Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-V1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Val294Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-V2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Val294Thr) | This study |

| pQZ-R3 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Arg301Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-R4 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Arg301Glu) | This study |

| pQZ-D1 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Asp304Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-D2 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Asp304Lys) | This study |

| pQZ-R5 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Arg305Ala) | This study |

| pQZ-R6 | pMMB206::tonB1 (Arg305Glu) | This study |

| pQZ-CEc-1 | pMMB206::tonB1-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pQZ-CEc-2 | pMMB206::tonB1-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pQZ-CPa-1 | pMMB206::tonBEc-tonB1 chimera | This study |

| pQZ-CPa-2 | pMMB206::tonBEc-tonB1 chimera | This study |

| pQZ-CPa-3 | pMMB206::tonBEc-tonB1 chimera | This study |

| pQZ-CPa-4 | pMMB206::tonBEc-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pQZ-NPa-1 | pMMB206::tonB1-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pQZ-NPa-2 | pMMB206::tonB1-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pQZ-NPa-3 | pMMB206::tonB1-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pQZ-NPa-4 | pMMB206::tonB1-tonBEc chimera | This study |

| pMAL-c2 | E. coli malE-fusion expression vector; Apr | New England BioLabs, Inc. |

| pQZ-TMF | pMAL-c2::tonB1 (Ser204-Arg342 of TonB1 fused to MalE) | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

Recombinant DNA methods.

All DNA isolations, manipulations, transformations, and conjugations were performed as described previously (64). Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, and Vent DNA polymerase were purchased from New England Biolabs. All enzymes were used as recommended by the manufacturers. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Cortec DNA Service Laboratories, Inc., Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by a PCR-based method (see below). The mutagenized tonB1 derivatives were cloned into the broad-host-range, low-copy-number cloning vector pMMB206. DNA sequencing was carried out by Cortec DNA Service Laboratories, Inc.

Construction of tonB1 mutations.

An in-frame deletion of 51 amino acids within the C-terminal region of TonB1 (from Asp260 to Ala310) was constructed by digestion of plasmid pQZ-06 (carrying the wild-type tonB1 gene) with SacII and NcoI, each of which cut once within the 3′ end of tonB1 and nowhere else on this plasmid. The restricted plasmid was recovered free of the 135-bp SacII-NotI fragment, treated with T4 DNA polymerase and Klenow to render the ends blunt, and recircularized via ligation to yield plasmid pQZ-C. The deletion was verified by nucleotide sequencing.

In-frame deletion of portions of the N-terminal extension (from Ser33 to Ile67 in pQZ-N1 and from Ser6 to Pro83 in pQZ-N2) of TonB1 was carried out by using a PCR-based mutagenesis protocol (30). The sequence upstream and downstream of the deletion endpoints was amplified in two PCRs. The first involved primers tonB-Pst and tonB-N1a (for pQZ-N1) or tonB-N2a (for pQZ-N2), and the second involved primers tonB-N1b (for pQZ-N1) or tonB-N2b (for pQZ-N2) and tonB-HindIII (tagged with a HindII cleavage site and anneals downstream of tonB1). The PCR mixtures (100 μl) contained 100 ng of chromosomal DNA as a template, 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Amersham Life Sciences), and 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Inc.) in 1× ThermoPol buffer. Mixtures were then heated to 95°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min, before finishing with 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were visualized on agarose gels and purified by using a Qiagen PCR purification kit. The purified PCR products were digested with PstI and SacI or SacI and HindIII, as appropriate, and cloned (in a three-piece ligation) into PstI-HindIII-restricted pMMB206. After digestion with SacI and treatment with T4 DNA polymerase (to remove non-tonB1-derived sequences), the deletions were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. A tonB1 deletion derivative encoding a TonB1 protein lacking the putative transmembrane domain (ΔPro82-Thr111; pQZ-TMD) was constructed as described above with the primers tonB-Pst and tonB-TMa (for the upstream sequence) and tonB-TMb and tonB-HindIII (for the downstream sequence). Finally, mutant tonB1 genes producing His98Gly (pQZ-H), Cys36Gly (pQZ-CY) and Met1Leu (pQZ-A) TonB1 derivatives were produced as described above, with internal primers carrying the desired mutation, such that after the three-piece ligation with PstI-HindIII-restricted pMMB206 and subsequent SacI and T4 polymerase treatment, a single base pair substitution had been achieved.

For the bulk of the point mutations introduced into tonB1, however, a simpler approach was employed. Again, tonB1 was amplified in two parts, except that a SacI site was not appended to the ends of the “internal” primers paired with tonB-Pst (for amplifying the 5′ part of the gene) or tonB-HindIII (for amplifying the 3′ part of the gene). Rather, these were phosphorylated at the 5′ ends (to permit their ultimate blunt-end ligation), and the sequences were immediately adjacent on the tonB1 gene. One of these internal primers carried the desired mutation, so that following PCR the resultant products could be digested with PstI or HindIII, as appropriate, and cloned into PstI-HindIII-restricted pMMB206 via a three-piece ligation to yield the desired mutant tonB1 gene. Similarly, chimeric E. coli tonB (tonBEc)-tonB1 genes were constructed by amplifying the appropriate 5′ portions of tonBEc (present on plasmid pQZ-TEC, a pMMB206 derivative carrying a 1.7-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pCG752) with primer tonBEc-Eco (anneals upstream of tonBEc) and one of several internal primers (which vary according to the position of the fusion junction) and the appropriate 3′ portions of tonB1 by using one of several internal primers and primer tonB-HindIII. The products were digested appropriately and cloned into EcoRI-HindIII-restricted pMMB206 via a three-piece ligation. Chimeric tonB1-tonBEc genes were constructed by amplifying the appropriate 5′ portions of tonB1 with primer tonB-Pst and one of several internal primers and the appropriate 3′ portions of tonBEc with one of several internal primers and primer tonBEc-HindIII (anneals downstream of tonBEc). Again, the PCR products were digested appropriately and cloned into PstI-HindIII-restricted pMMB206. All mutations and chimeras were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. The primer sequences are available on request.

Purification of a TonB1-maltose-binding protein fusion protein and generation of a polyclonal antibody.

To facilitate the purification of TonB1 for the purpose of raising antibodies, the 3′ end of tonB1, encompassing the coding region for amino acids Ser204 to Arg342, was first cloned into the pMAL-c2 vector (New England Biolabs) on a ca. 400-bp PCR fragment to create an in-frame fusion between the pMAL-c2-encoded E. coli malE gene and tonB1. The 3′ end of the tonB1 gene was amplified from the P. aeruginosa PAO6609 chromosomal DNA with primers tonB1-C1 (5′-AACGGAAGCA-CGGAAGCATCCAGCCAG-3′) and tonB1-C2 (5′-AATTAAGCTTCGTCTGCGAG-ACCTACC-3′; the HindIII site is underlined). The reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 100 ng of chromosomal DNA, 60 pM concentrations of each primer, 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Amersham Life Science), and 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) in 1× ThermoPol buffer. The mixture was heated to 95°C for 2 min and then subjected to 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, before finishing with a 10-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and were purified with a Qiagen PCR purification kit. After digestion with HindIII, which left one end of the PCR fragment blunt ended, the tonB1-containing PCR product was cloned into XmnI-HindIII-restricted pMAL-c2 to generate pQZ-TMF. This latter construct was transferred into E. coli DH5α, and expression and purification of the TonB1-maltose-binding protein fusion protein was carried out according to a protocol supplied with the pMAL-c2 vector. Antibodies to the fusion protein were then raised in chickens by RCH Antibodies, Sydenham, Ontario, Canada.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western immunoblotting.

P. aeruginosa or E. coli cells harboring cloned tonB1 derivatives and cultured overnight in antibiotic-containing L broth, DTSB, or iron-deficient succinate minimal medium were inoculated into fresh medium (3 ml) at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 and incubated with shaking until the OD600 of the culture had reached 0.5. Expression of the TonB1 derivatives was then induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) at 20 μM, a concentration shown to yield levels of TonB1 reminiscent of chromosomally encoded protein in P. aeruginosa strain PAO6609. In the absence of IPTG, TonB1 was undetectable in Western immunoblots, while at higher IPTG concentrations substantial breakdown of TonB1 became evident. After 1 h of IPTG induction, 0.5 ml of culture was harvested by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge (1 min). After resuspension in 0.5 ml of 10% (wt/vol) trichloroacetatic acid, cells were incubated on ice for 45 min and subsequently recovered by centrifugation (1 min in a microcentrifuge). The cell pellets were resuspended in 60 μl of sample loading buffer and sonicated briefly for 15 s at 50% power by using a Vibrasonic sonic disruptor (Sonics & Materials, Inc., Danbury, Conn.), and 10 μl was loaded onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis (49), the separated proteins were electroblotted (30 mA overnight at 4°C) onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) and then processed as described previously (70), with murine anti-TonBEc monoclonal antibodies 4H4 or 1C3 (41) (diluted 1:10,000; E. coli extracts) or a chicken polyclonal anti-MalE-TonB fusion antibody (diluted 1:10,000; P. aeruginosa extracts) as the primary antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-coupled rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Amersham Life Sciences), diluted 1:10,000, and the horseradish peroxidase-coupled rabbit anti-chicken immunoglobin (BioCan, Inc.), diluted 1:10,000, were used as secondary antibodies. A prestained molecular weight marker (Bio-Rad) was coelectrophoresed and blotted to permit estimation of the size of the various TonB derivatives being examined in the aforementioned blots.

Triparental matings.

To introduce the plasmid pMMB206 and its tonB1-carrying derivatives into P. aeruginosa K1040 required a previously described triparental mating procedure (74). Plasmid-containing K1040 cells were selected on L-agar plates containing streptomycin (to counterselect the E. coli strains) and chloramphenicol, and plasmid DNA was prepared from P. aeruginosa recipients by using the miniprep procedure (64) to confirm successful plasmid transfer.

Pyoverdine-dependent growth promotion.

As a measure of mutant TonB1 function in iron acquisition, growth of tonB1 plasmid carrying P. aeruginosa K1040 under iron-restricted conditions upon pyoverdine supplementation was assessed. The K1040 strain lacks tonB1 and is unable to synthesize pyoverdine. In the presence of a cloned, functional tonB1 gene, however, the addition of exogenous pyoverdine can promote growth under conditions of iron restriction. Thus, P. aeruginosa K1040 carrying one of several mutant tonB1 plasmids was cultured overnight in L broth supplemented with chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) and diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in succinate minimal medium supplemented with methionine (100 μg/ml), FeCl3 (200 μM), and chloramphenicol (16 μg/ml). After overnight growth at 37°C, cells were harvested by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge (1 min), washed three times (1 min) with 1 ml of iron-free succinate minimal medium, and resuspended in 1 ml of the same medium. Then, 100 μl of cell suspension was plated onto the surface of methionine-supplemented iron-deficient succinate minimal medium plate containing 180 μg of ethylenediamine di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid) (EDDHA)/ml and 20 μM IPTG (to induce the tonB1 genes cloned into pMMB206). Filter disks (6 mm in diameter; Becton Dickinson) impregnated with 8 μl of pyoverdine (50-mg/ml stock) were then placed on the plates. After incubation at 37°C for ca. 40 h, the plates were examined for evidence of growth in the region surrounding the filter discs, and the diameter of any zone of growth was measured.

Vitamin B12-dependent growth promotion.

The methionine requirement of an E. coli metE auxotroph can be met by vitamin B12, the uptake of which is TonB dependent. To assess mutant TonB1 function in E. coli, the growth of tonB1-carrying E. coli RK5015 (metE tonB) on minimal medium plates supplemented with vitamin B12 was examined. tonB1 plasmid-carrying E. coli RK5015 strains were cultured overnight in L broth and diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in an iron-deficient glucose minimal medium supplemented with 1 mM l-arginine, 1 mM methionine, 10 μM thiamine, and 20 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. After incubation at 37°C overnight, cells were harvested by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge (1 min), washed three times (1 min) with 1 ml of glucose minimal medium, and resuspended in 1 ml of the same medium. Next, 100 μl of cell suspension was plated onto the surface of glucose minimal medium plates supplemented with arginine, thiamine, and 20 μM IPTG (to induce the tonB1 genes cloned into pMMB206). Filter disks (6 mm in diameter; Becton Dickinson) impregnated with 8 μl of vitamin B12 (10 μM stock) were then placed on the plates. After incubation for ca. 40 h at 37°C, plates were examined for evidence of growth in the region surrounding filter disks, and the diameter of any zone of growth observed was measured.

Growth assay.

To assess the impact of tonB1 mutations on growth of tonB1-carrying E. coli KP1032 (ΔtonB::Kan) under conditions of iron limitation, KP1032 harboring pMMB206::tonB1 derivatives was cultured overnight in chloramphenicol-supplemented L broth (1 ml), washed three times with DTSB (1 ml), and inoculated at a 1:249 dilution into DTSB containing EDDHA (50 μg/ml) and IPTG (20 μM). Cell growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 of the cultures over time.

RESULTS

Functional significance of the TonB1 N terminus.

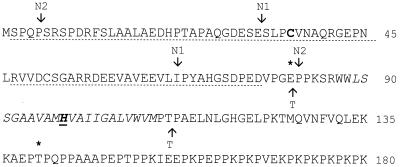

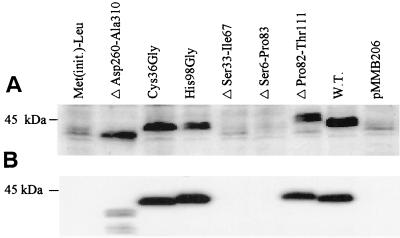

P. aeruginosa K1040 is a pyoverdine-deficient tonB1 deletion strain that fails to grow in iron-restricted medium (i.e., with EDDHA) upon pyoverdine supplementation (Table 2) as a result of a defect in pyoverdine-mediated iron acquisition (a TonB1-dependent process [60]). In the presence of a functional tonB1 gene (e.g., plasmid pQZ-06), however, exogenous pyoverdine is able to restore the growth of this mutant on an EDDHA-containing minimal medium (Table 2), a finding consistent with the restoration of pyoverdine-mediated iron uptake. By using pyoverdine promotion of P. aeruginosa K1040 growth on EDDHA-containing minimal medium as a measure of TonB1 function, growth of P. aeruginosa K1040 harboring various mutant tonB1 plasmids on pyoverdine-supplemented, EDDHA-containing minimal medium was assessed. Initially, the functional significance of the novel N-terminal extension present upstream of the putative membrane-spanning domain of TonB1 was examined. Deletion of 35 amino acids (from Ser33 to Ile67 [Fig. 1]) or 78 amino acids (from Ser6 to Pro83 [Fig. 1]) abrogated TonB1 activity (pQZ-N1 and pQZ-N2 [Table 2]), apparently as a result of an attendant destabilization of the mutant proteins (Fig. 2A). The pQZ-N1- and pQZ-N2-encoded TonB1 proteins were also unstable in the E. coli tonB strain RK5015 (Fig. 2B) and failed to facilitate vitamin B12-promoted growth of this metE mutant on glucose minimal media, in contrast to wild-type tonB1 (pQZ-06) (Table 2). Uptake of vitamin B12, which can overcome the methionine requirement of this mutant, is TonB dependent, making vitamin B12-promoted growth of RK5015 a measure of TonB1 function in E. coli.

TABLE 2.

Influence of tonB1 mutations on TonB1 activity in P. aeruginosa and E. coli

| Plasmid | TonBa | Zone of growth (diam [cm])

|

Growth (OD600) of E. coli KP1032d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa K1040b | E. coli RK5015c | |||

| pQZ-06 | Wild type | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.65 |

| pMMB206 | 0 | 0 | ||

| pQZ-A | Met1Leu | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-C | ΔAsp260-Ala310 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| pQZ-CY | Cys36Gly | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.54 |

| pQZ-H | His98Gly | 2.6 | 0 | 0.02 |

| pQZ-N1 | ΔSer33-Ile67 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| pQZ-N2 | ΔSer6-Pro83 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| pQZ-T | ΔPro82-Thr111 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-Y1 | Tyr264Ala | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-Y2 | Tyr264Phe | 0 | 0 | 0.06 |

| pQZ-P1 | Pro265Ala | 2.7 | 2.1 | 0.18 |

| pQZ-P2 | Pro265Gly | 2.6 | 2.3 | 0.10 |

| pQZ-Q1 | Gln269Ala | 2.5 | 2 | 0.77 |

| pQZ-Q2 | Gln293Ala | 2.6 | 2.2 | 0.15 |

| pQZ-V1 | Val294Ala | 2.7 | 2.3 | 0.12 |

| pQZ-V2 | Val294Thr | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0.14 |

| pQZ-E1 | Glu274Ala | 0 | 0 | 0.01 |

| pQZ-E3 | Glu274Ala/Asp304AsnN | 2.5 | 0 | 0.02 |

| pQZ-E2 | Glu274Lys | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| pQZ-K1 | Lys278Ala | 1 | 0 | 0.04 |

| pQZ-K2 | Lys278Glu | 1.1 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-R1 | Arg288Ala | 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.94 |

| pQZ-R2 | Arg288Glu | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.79 |

| pQZ-R3 | Arg301Ala | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.45 |

| pQZ-R4 | Arg301Glu | 2.6 | 2 | 0.60 |

| pQZ-D1 | Asp304Ala | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| pQZ-D2 | Asp304Lys | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| pQZ-R5 | Arg305Ala | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.67 |

| pQZ-R6 | Arg305Glu | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.38 |

Alterations present in the TonB1 proteins encoded by the indicated plasmids are highlighted.

The TonB1-deficient P. aeruginosa K1040 strain harboring wild-type tonB1 or the indicated tonB1 plasmids were plated onto the surface of an iron-deficient succinate minimal plate containing 180 μg of EDDHA/ml and 20 μM IPTG (to induce the tonB genes). Filter disks impregnated with 8 μl of pyoverdine (50-mg/ml stock) were placed on the plates, and the zones of growth (i.e., diameter) appearing after ca. 40 h at 37°C were measured. The data are representative of three separate experiments.

The tonB metE mutant E. coli strain RK5015 harboring wild-type tonB1 or the indicated tonB1 plasmids were plated onto the surface of glucose minimal plates containing 20 μM IPTG. Filter disks impregnated with 8 μl of vitamin B12 (10 μM stock) were placed on the plates, and the zones of growth (i.e., diameter) appearing after ca. 40 h at 37°C were measured. The data are representative of three separate experiments.

The E. coli tonB mutant KP1032 carrying the indicated plasmids was inoculated into DTSB medium containing 50 μg of EDDHA/ml and 20 μM IPTG at an OD600 of 0.05, and growth (i.e., the increase in cell density as measured by OD600) was monitored for 10 h. The values for final OD600 at 10 h are shown above. The data are representative of three independent experiments and have been corrected for background growth (OD600 = 0.18) of KP1032 carrying pMMB206.

FIG. 1.

N terminus of TonB1. The deletion endpoints for N-terminal deletion 1 of pQZ-N1 (N1), N-terminal deletion 2 of pQZ-N2 (N2), and the transmembrane domain deletion of pQZ-T (T) are indicated. The putative transmembrane domain is italicized, and a histidine residue that corresponds to an essential histidine in the transmembrane domain of TonBEc is in boldface and underlined. The novel N-terminal extension of TonB1 is indicated by a dotted underline, and the Cys residue that was mutated here is in boldface. Asterisks identify the residues at the fusion junction for chimeras CEc-1 (E81) and CEc-2 (T140) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Expression of mutant TonB1 proteins in P. aeruginosa K1040 (A) and E. coli RK5015 (B). Cell extracts of P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli RK5015 harboring plasmids expressing the indicated TonB1 mutant proteins were electrophoresed, electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with polyclonal antibodies raised against a MalE-TonB1 (C terminus) fusion (A) or 4H4 monoclonal antibodies to TonBEc (B). 4H4 antibodies readily detected TonB1 in E. coli but failed to do so in P. aeruginosa due to an excessive amount of cross-reactivity as reported previously (41). The migration position of the 45-kDa molecular mass standard is shown on the left. Met(init.)-Leu, TonB1 with a Leu substitution of initiation Met; W.T., wild-type TonB1; pMMB206, vector control (i.e., no TonB1 protein). Expression is shown for cells cultivated in L broth, although cultivation in minimal medium or DTSB yielded comparable results for representative TonB1 derivatives.

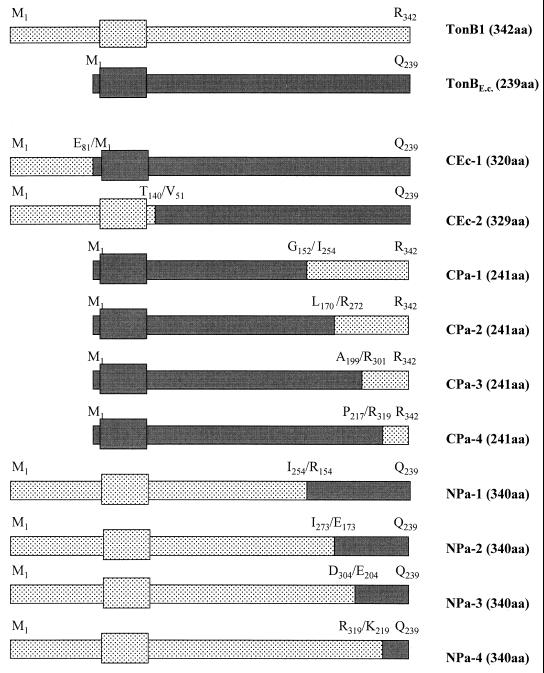

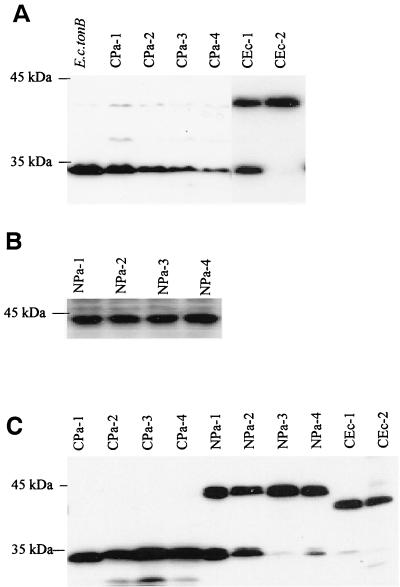

Unlike TonB1, which is functional in both P. aeruginosa and E. coli, the E. coli TonB (TonBEc) is functional only in E. coli (data not shown), perhaps because it lacks the long N-terminal extension of TonB1. To assess this, the TonB1 N-terminal extension (from Met1 to Glu81 [Fig. 1]) was fused onto the N terminus of TonBEc, immediately upstream of the Met1 residue of TonBEc (on pQZ-CEc-1 [Fig. 3]). In addition, the N terminus and transmembrane domain of TonBEc (Met1 to Met50 [Fig. 1]) was swapped with the corresponding region of TonB1 (Met1 to Thr140) (pQZ-CEc-2 [Fig. 3]), again creating a TonBEc chimera containing the TonB1 N-terminal extension. TonB proteins of the expected size were detected in pQZ-CEc-1- and pQZ-CEc-2-carrying strains of P. aeruginosa K1040 (Fig. 4A). Still, these chimeras were generally inactive, with very weak growth being detected only for the pQZ-CEc-1-carrying K1040 strain on pyoverdine-supplemented iron-restricted medium (Table 3). Interestingly, the TonB1 N-terminal extension did not adversely affect expression (Fig. 4C) or activity (Table 3) of these TonBEc chimeras in E. coli RK5015. Thus, residues C terminal to the transmembrane domain are responsible for the failure of TonBEc to function in P. aeruginosa and not the lack of the unique N-terminal extension.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of TonB1-TonBEc chimeras. The extent of TonB1 (stippled) and TonBEc (shaded) present in each of the chimeric constructs is indicated relative to the intact proteins shown at the top. The identity of the first and last amino acid residue for each of the contributing TonB segments is indicated. The size of the chimera (in amino acid [aa] residues) is indicated on the right in parentheses. The box present near the N terminus of both proteins represents the transmembrane domain.

FIG. 4.

Expression of TonB1-TonBEc chimeras in P. aeruginosa K1040 (A and B) and E. coli RK5015 (C). Cell extracts of P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli RK5015 harboring plasmids expressing the indicated TonB1 mutant proteins were electrophoresed, electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with polyclonal antibodies raised against a MalE-TonB1 (C terminus) fusion (A), 1C3 monoclonal antibodies to TonBEc (B), or 4H4 monoclonal antibodies to TonBEc (C). As the anti-TonB1 antiserum was raised against the C terminus of TonB1, it was not useful in detecting expression of the NPa series of chimeras, which lacked the TonB1 C terminus. Since 4H4 reacted well with both proteins in E. coli, it was useful in assessing expression of all of the chimeras in this organism. The migration positions of the 45- and 35-kDa standards are shown on the left.

TABLE 3.

Activity of TonB1-TonBEc chimeras in P. aeruginosa and E. coli

| Plasmid | TonB (sequences)a | Zone of growth (diam [cm])

|

Growth (OD600) of E. coli KP1032d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa K1040b | E. coli RK5015c | |||

| pQZ-06 | Wild type | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.65 |

| pMMB206 | 0 | 0 | ||

| pQZ-CPa-1 | TonBEc (1-152)-TonB1 (254-342) | 2.6 | 3.2 | 0.66 |

| pQZ-CPa-2 | TonBEc (1-170)-TonB1 (272-342) | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-CPa-3 | TonBEc (1-199)-TonB1 (301-342) | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-CPa-4 | TonBEc (1-217)-TonB1 (319-342) | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pQZ-NPa-1 | TonB1 (1-254)-TonBEc (154-239) | 0 | 2.2 | 0.59 |

| pQZ-NPa-2 | TonB1 (1-273)-TonBEc (173-239) | 0 | 2.8 | 0.76 |

| pQZ-NPa-3 | TonB1 (1-304)-TonBEc (204-239) | 0 | 2.8 | 0.73 |

| pQZ-NPa-4 | TonB1 (1-319)-TonBEc (219-239) | 0 | 0 | 0.79 |

| pQZ-CEc-1 | TonB1 (1-81)-TonBEc (1-239) | (1)e | 2.9 | 0.43 |

| pQZ-CEc-2 | TonB1 (1-140)-TonBEc (51-239) | 0 | 2.7 | 0.88 |

The positions of the corresponding amino acid sequences of TonB1 and TonBEc encoded by the chimeric tonB genes present on the indicated plasmids are indicated in parentheses.

The TonB1-deficient P. aeruginosa K1040 strain harboring wild-type tonB1 or the indicated tonB1-tonBEc plasmids were plated onto the surface of an iron-deficient succinate minimal plate containing 180 μg of EDDHA/ml and 20 μM IPTG (to induce the tonB genes). Filter disks impregnated with 8 μl of pyoverdine (50-mg/ml stock) were placed on the plates, and the zones of growth (i.e., diameter) appearing after ca. 40 h at 37°C were measured. The data are representative of three separate experiments.

The tonB metE mutant E. coli strain RK5015 harboring wild-type tonB1 or the indicated tonB1-tonBEc plasmids were plated onto the surface of glucose minimal plates containing 20μM IPTG. Filter disks impregnated with 8 μl of vitamin B12 (10 μM stock) were placed on the plates, and the zones of growth (i.e., diameter) appearing after ca. 40 h at 37°C were measured. The data are representative of three separate experiments.

The E. coli tonB mutant KP1032 carrying the indicated plasmids was inoculated into DTSB medium at an OD600 of 0.05, and growth (i.e., the increase in cell density as measured by OD600) was monitored for 10 h. The final OD600 at 10 h is shown above. The data are representative of three independent experiments and have been corrected for background growth (OD600 = 0.18) of KP1032 carrying pMMB206.

Weak growth.

An interesting feature of the TonB1 N-terminal extension is the presence of two cysteine residues (Cys36 and Cys51 [Fig. 1]). To determine whether these were important for function, attempts were made to mutate both residues individually. Despite several attempts, a Cys51Gly mutation was not obtained. In contrast, Cys36 was readily replaced with a Gly residue (pQZ-CY), and the expression and activity of this TonB1 derivative was assessed. P. aeruginosa K1040 carrying pQZ-CY did express a TonB1 protein (Fig. 2A) and was able to grow in a pyoverdine-supplemented iron-restricted medium (Table 2), indicating that it was functional in P. aeruginosa. Similarly, the Cys36Gly TonB1 was expressed (Fig. 2B) and functional (Table 2) in E. coli RK5015. Thus, while the N-terminal extension is important for stable TonB1 production, the Cys35 residue is dispensable.

TonB1 transmembrane domain.

The transmembrane domain of TonBEc occurs upstream of a proline-rich region, and a hydrophobic, presumed membrane-spanning (membrane anchor) region has been similarly identified upstream of a proline-rich region in TonB1 (from Ser85 to Met109 [Fig. 1]) (60). To confirm the functional significance of this region, amino acids Pro82 through Thr111 were deleted (Fig. 1) from TonB1 (on plasmid pQZ-T), and the impact on TonB1 expression and function was assessed in P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli strain RK5015. Although the protein was expressed in both tonB mutants (Fig. 2, lane 7), the pQZ-T-containing strains were unable to grow on pyoverdine (K1040)- or vitamin B12 (RK5015)-supplemented minimal media (Table 3), indicating that the transmembrane domain-deleted TonB1 was nonfunctional. Curiously, the deletion derivative exhibited a lower mobility on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, despite its smaller size. This likely reflects the well-known anomalous migration of the native protein, which migrates to a position typically 10 kDa higher than expected.

Within the transmembrane domain of TonBEc lies an essential histidine residue (His20) that is conserved in this location in several TonB proteins (72). A similarly positioned histidine residue can be found within the putative transmembrane domain of the TonB1 protein of P. aeruginosa (His98 [Fig. 1]). Mutation of this residue (His98Gly; pQZ-H) did not adversely affect expression of the pQZ-H-encoded TonB1 protein in P. aeruginosa K1040 (Fig. 2A), and the mutant protein permitted excellent growth of K1040 in a pyoverdine-supplemented, iron-restricted medium (Table 2), indicating that TonB1 with the His98Gly substitution was fully functional. In contrast, and despite excellent expression in E. coli RK5015 (Fig. 2B), the His98Gly TonB1 protein was inactive in RK5015 (Table 3). Thus, TonB1, like its E. coli counterpart, requires this conserved transmembrane histidine residue for function in E. coli, though not for function in P. aeruginosa.

Functional importance of the conserved C-terminal region of TonB1.

The highest degree of similarity between TonB1 and other TonB proteins, including that of E. coli, lies downstream of the proline-rich region, within the C terminus of the protein (Fig. 5). This region of E. coli TonB is important for stable expression of the protein (3) and for interaction with outer membrane receptors (40). Disruption of the TonB1 C-terminal region by deletion of 51 amino acids (from Asp260 to Ala310; plasmid pQZ-C) from this 342-amino-acid protein produced a protein (Fig. 2A) which was also inactive in P. aeruginosa K1040 (Table 2) and was unstable (Fig. 2B) and inactive (Table 2) in E. coli RK5015, confirming the functional significance of the TonB1 C terminus. To assess the functional importance of a number of residues found within this region and conserved in many TonB proteins (Fig. 5), several of these residues were mutated, and the resultant TonB1 proteins were expressed in P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli RK5015. A total of 13 conserved residues were individually altered, and 10 of the resultant TonB1 proteins were well expressed in both K1040 (Fig. 6A) and RK5015 (Fig. 6B). Mutations in the highly conserved Gly residues at positions 275 and 287 (Gly275Phe and Gly287Phe) produced an unstable TonB1 that was proteolyzed (data not shown) and thus was not assayed for function. A Val279Gly substitution yielded a similarly unstable protein (data not shown) that was not assayed for function, and attempts at constructing a Val279Ala substitution were unsuccessful. Of the 10 stable TonB1 derivatives 7, including those with substitutions at Pro265 (pQZ-P1 and pQZ-P2), Gln269 (pQZ-Q1), Arg288 (pQZ-R1 and pQZ-R2), Gln293 (pQZ-Q2), Val294 (pQZ-V1 and pQZ-V2), and Arg305 (pQZ-R5 and pQZ-R6), were functional in P. aeruginosa K1040 (Table 2). Substitutions at Tyr264 (pQZ-Y1 and pQZ-Y2), Glu274 (pQZ-E1 and pQZ-E2), and Asp304 (pQZ-D1 and pQZ-D2) appeared to fully compromise TonB1 function in P. aeruginosa, while substitutions at Lys278 (pQZ-K1 and pQZ-K2) substantially reduced its activity in this organism (Table 2). The various TonB1 mutants behaved similarly in E. coli RK5015, although TonB1 mutated at Lys278 was completely inactive in E. coli (Table 2). During transfer of pQZ-E1 (TonB1 Glu274Ala) to P. aeruginosa strain K1040, several fast-growing variants were isolated which appeared to have overcome the tonB1 mutation of this strain. The plasmid prepared from one of these, dubbed pQZ-E3, carried the original inactivating Glu274Ala mutation and a second mutation, Asp304Gln, which appeared to be an intragenic suppressor. Indeed, reintroduction of pQZ-E3 into P. aeruginosa K1040 fully restored growth of the mutant in pyoverdine-supplemented, iron-restricted medium (Table 2), indicating that TonB1 activity had been restored as a result of the Asp304Gln mutation. This suppression was, however, specific to P. aeruginosa K1040 and was not observed when pQZ-E3 was introduced into E. coli RK5015 (Table 2), although the protein was well expressed in this organism (data not shown). Residue Arg301 of the TonB1 protein was one of several C-terminal arginines that were not well conserved in the other TonB proteins (Fig. 5). To assess whether this might reflect a unique structural or functional aspect of TonB1, substitutions were made at this residue (pQZ-R3 and pQZ-R4). The resultant Arg301Ala and Arg301Glu TonB1 derivatives were expressed in both P. aeruginosa K1040 (Fig. 6A) and E. coli KP1032 (Fig. 6B) and were fully functional (Table 2).

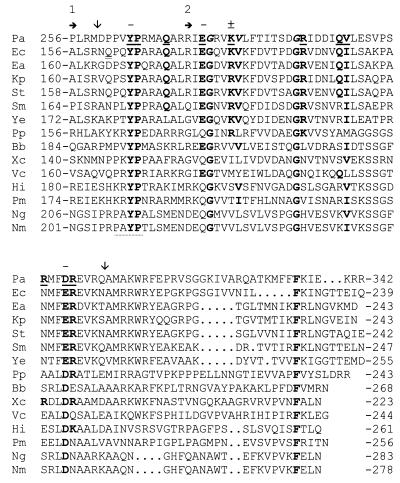

FIG. 5.

Multiple alignment of the TonB1 C terminus with the C terminus of other TonB proteins. Residues mutated in TonB1 are in boldface and underlined and, where conserved (identical or conservative change) in other TonB proteins, are in boldface. Residues in TonB1 that are in boldface and italicized were also mutated but yielded truncated, apparently proteolyzed products that were not assayed for function. The conservation of these residues in other TonB proteins is also noted by boldface type. Vertical arrows indicate the deletion endpoints for the pQZ-C-encoded C-terminal deletion. Horizontal arrows indicate the fusion junctions for the TonBEc-TonB1 chimeras CEc-1 (4) and CEc-2 (1). A “−” above a residue indicates that a mutation here abrogates TonB1 function with respect to pyoverdine-dependent growth promotion under iron-restricted conditions. A “±” above a residue indicates that a mutation here substantially reduces but does not eliminate TonB1 activity. Given the limited amount of sequence available downstream of tonB1 (at the time these studies were initiated) and the PCR mutagenesis approach used, it was not possible to mutate conserved residues nearer the C terminus. A highly conserved “PXYP” motif is also indicated (dashed underline). Numbers bracketing the aligned sequences represent the position of the first (left) and last (right) amino acid residue of each sequence shown. Abbreviations (GenBank accession numbers): Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (U23764); Ec, E. coli (K00431); Ea, Enterobacter aerogenes (X68477); Kp, Klebsiella pneumoniae (X68478); St, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (X56434); Sm, Serratia marcescens (X60996); Ye, Yersinia enterocolitica (X67332); Pp, Pseudomonas putida (X70139); Bb, Bordetella bronchiseptica (AF087669); Xc, Xanthomonas campestris (Z95386); Vc, Vibrio cholerae (AF047974); Hi, Haemophilus influenzae (U04996); Pm, Pasteurella multocida (AF070473); Ng, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (U79563); Nm, Neisseria meningitidis (U77738).

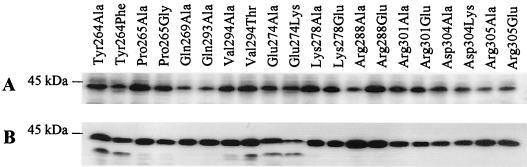

FIG. 6.

Expression of C-terminally mutated TonB1 proteins in P. aeruginosa K1040 (A) and E. coli RK5015 (B). Cell extracts of P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli RK5015 harboring plasmids expressing the indicated TonB1 mutant proteins were electrophoresed, electroblotted, and probed with polyclonal antibodies raised against a MalE-TonB1 (C terminus) fusion (A) or 4H4 monoclonal antibodies to TonBEc (B). The migration position of the 45-kDa molecular mass standard is shown on the left.

Activity of TonB1-TonBEc chimeras.

The lack of activity of the TonBEc chimeras carrying the TonB1 N-terminal extension (pQZ-CEc-1 and pQZ-CEc-2 [Table 3]) in P. aeruginosa suggested that sequences C terminal to the transmembrane domain were important for TonB1 activity in P. aeruginosa. Moreover, the aforementioned mutational analysis indicated that several residues in the C terminus of TonB1 were likewise functionally important. To address these issues, TonB1-TonBEc chimeras were constructed by swapping various portions of the C termini of these proteins and expressed in the TonB-deficient P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli RK5015 strains. TonB1 derivatives carrying the N terminus of TonBEc and the C terminus of TonB1 (CPa-1 through CPa-4 [Fig. 3]) were all well expressed in both K1040 (Fig. 4A) and RK5015 (Fig. 4C). Swapping the last 93 amino acids of TonBEc with the corresponding region of TonB1 (CPa-1 [Fig. 3]) produced a protein that was active, with pQZ-CPa-1-carrying P. aeruginosa K1040 and E. coli RK5015 growing very well in pyoverdine (K1040)- and vitamin B1- (RK5015)-supplemented minimal medium (Table 3). This finding contrasted with P. aeruginosa K1040 expressing the native E. coli TonB protein, which failed to grow on the pyoverdine-supplemented medium. None of the TonBEc-TonB1 chimeras in which smaller portions (i.e., 75 [TonB CPa-2], 45 [TonB CPa-3], and 27 [TonB CPa-4] amino acids [Fig. 3]) of the C terminus were swapped with the corresponding region of TonB1 were, however, active in either organism (Table 3). The corresponding TonB1-TonBEc chimeras, in which the TonB1 N terminus was fused to various portions of the TonBEc C terminus (NPa-1 to NPa-4 series [Fig. 3]) were all expressed in both organisms (Fig. 4B and C) although inactive in P. aeruginosa K1040 (Table 3). Interestingly, all but the TonB1 NPa-4 construct, in which the last 23 amino acids of TonB1 were replaced with the last 21 amino acids of TonBEc (Fig. 3), were active in E. coli RK5015 (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The most striking feature of the P. aeruginosa TonB1 protein is the unusual N-terminal extension of ca. 90 amino acid residues which occurs upstream of a probable transmembrane domain and thus occurs in the cytoplasm. This contrasts with all other known TonB proteins which possess minimal sequence upstream of their transmembrane domains. This region is indispensable for stable TonB1 production (and thus activity) in both P. aeruginosa and E. coli. Still, appending this region to E. coli TonB was generally unable to render the E. coli protein active in P. aeruginosa. Indeed, although the highest degree of similarity between TonB1 and TonBEc lies within the C-terminal end of these proteins, and the expectation was that the novel N terminus would be important for function of, for example, a TonB1-TonBEc chimera in P. aeruginosa, the work presented here clearly shows that the TonB1 C terminus and not its N terminus are critical for TonBEc function in this organism. Thus, a chimera comprised predominantly of TonBEc but harboring a large C-terminal domain of TonB1 (89 amino acids; CPa-1) was active in P. aeruginosa. Since the C-terminal end of the molecule is the region implicated in receptor recognition (31, 40), one can only surmise that the E. coli TonB lacks key residues necessary for this in P. aeruginosa. This view is consistent with the observation, for example, that chimeras comprised of the TonBEc C terminus were active in E. coli but not in P. aeruginosa (i.e., the TonBEc C terminus recognizes E. coli receptors but not those of P. aeruginosa). The fact that wild-type TonB1 and the CPa-1 chimera are active in both organisms simply indicates that the TonB1 C terminus is able to recognize receptors in both P. aeruginosa and E. coli. Possibly, the lack of activity of the CPa-2 to CPa-4 series results from a lack of dimerization (the crystal structure of a TonBEc C-terminal fragment reveals dimer formation [14]), while the lack of activity of the NPa-1 to NPa-4 series (in P. aeruginosa) is due to the failure to recognize receptors in P. aeruginosa. The fact that the latter are active in E. coli indicates that if dimerization is relevant in vivo for function, they must be capable of dimerization. That TonB1 also plays a role in drug efflux and resistance suggests a need for TonB1 to be able to interact with a variety of “receptors” and may explain its ability to function in E. coli. In contrast, TonBEc may be more specific in its receptor interactions. Still, none of this sheds any light on the function of the novel N-terminal extension of TonB1 (beyond stabilizing TonB1), shown here to be dispensable for the activity of TonBEc-TonB1 chimeras in P. aeruginosa. It may be, however, that it is important for TonB1 activity in TonB1-dependent processes not examined here.

Despite the demonstrated importance of Gln160 for TonBEc function and interaction with outer membrane receptors in E. coli (13), E. coli-Klebsiella pneuomoniae (TonBEc-TonBKp) (11), and E. coli-Serratia marcescens (TonBEc-TonBSm) (72) TonB chimeras lacking this residue are still functional. Similarly, TonB1-TonBEc chimeras lacking this residue were also functional in E. coli, suggesting that the overall conformation of this region and not the presence of a specific residue is important for receptor interaction. Intriguingly, one of the aforementioned TonBEc-TonBSm chimeras, reminiscent of our CPa-1 chimera, had the first 152 residues of TonBEc fused to the last 86 residues of TonBSm and was active, while a second TonBEc-TonBSm derivative, in which residues 153 to 180 of TonBEc were replaced by the TonBSm counterpart, was inactive. The former chimera would contain the PXYP region (PXYP is a highly conserved motif in TonB proteins [Fig. 5]), as well as downstream sequences of TonBSm, while the latter contained the PXYP region of TonBSm and downstream sequences of TonBEc. This could be explained by an inability of the PXYP region of TonBSm to interact with downstream sequences of TonBEc, a finding consistent with the idea of intramolecular interactions between these regions of a functional TonB protein. This region is, unfortunately, not included in the crystal structure of the dimeric C terminus of TonBEc (14). Interestingly, the second Pro (Pro265) of this motif is dispensable for TonB1 function in P. aeruginosa, though not in E. coli, raising some questions as to the motif's overall functional significance.

As with other TonB proteins, the cytoplasmic membrane anchor region of TonB1 is critical for function, and deletion of the presumed membrane-spanning segment of TonB1 obviates activity. This region of TonBEc has been implicated in interactions with ExbB, and a Val17 deletion within the membrane anchor is known to disrupt this interaction and inactivate the protein (43). Our observation that mutation of a conserved His98 (equivalent to His20 in TonBEc and required for activity of TonBEc [72]) obviates TonB1 activity in E. coli may also be explained by disruption of an interaction with ExbB. TonB1 activity is compromised in a tolQ exbB double mutant of E. coli (Q. Zhao, unpublished data), indicating that this protein does require ExbB for activity, at least in E. coli. Still, the His98 mutation fails to obviate activity in P. aeruginosa, and the P. aeruginosa exbBD homologues are not required for TonB1-dependent iron uptake (76). While it is tempting to suggest that TonB1 does not work with auxilliary proteins in P. aeruginosa, the possibility exists that it works with hitherto unidentified proteins. Homologues of the tol genes, which can functionally replace the exb genes of E. coli have been identified in P. aeruginosa (16), although mutation of these appear to be lethal (16; Zhao, unpublished), precluding ready assessment of their involvement in TonB1-dependent processes. A second set of exbBD homologues (exbB2 and exbD2; also known as PA0693 and PA0694) has been identified in the recently completed P. aeruginosa genome sequence (http://www.pseudomonas.com/) (71), linked to a gene (PA0695) whose predicted product shows weak similarity to known tonB proteins (sequences deposited with GenBank under accession number AE004505). Whether these are required for TonB1-mediated iron acquisition in P. aeruginosa remains to be tested.

Despite the presence of one (tonB2) (76) and possibly two (PA0695; see above), additional tonB homologues in P. aeruginosa, the studies reported here are restricted to TonB1 activity. The assay strain, P. aeruginosa K1040, is genotypically PA0695 ΔtonB1 tonB2+ and is unable to grow under any of the assay conditions used to assess TonB function. Growth is, in fact, seen only when TonB1 or its functional mutant derivatives are expressed in this strain, indicating that neither TonB2 nor PA0695 is contributing to any of the TonB-dependent processes being assayed.

The observation that a Asp304Gln mutation in TonB1 overcame the negative impact of a Glu274Ala mutation in this protein is consistent with regions of TonB1 in the vicinity of these residues interacting, although it is also possible that these regions play a role in monomer-monomer interaction in what may be a dimeric TonB1 protein. Examination of the crystal structure of the TonBEc C-terminal dimer (14), however, reveals that these residues (conserved in both TonBEc and TonB1) are not particularly close in individual monomers (ca. 5-Å separation) and do not occur in regions where monomers contact. Thus, the nature of the intragenic suppression remains a mystery. While one might speculate that mutations at the C terminus that inactivate TonB1 function do so by interfering with TonB1 interactions with outer membrane receptors (and that intragenic suppressors restore such interactions), this has yet to be tested. Still, it has been shown that substitutions at Tyr215 in TonBEc compromise the protein's activity, without disrupting its interaction with an outer membrane receptor (40). Whether such mutations interfere with dimerization or some other feature of TonB activity remains to be seen.

TonB activity will reflect protein levels as well as the assay employed. For this reason, tonB1 and its mutant derivatives were cloned into a regulated expression vector and induced to yield levels that were comparable to that provided by the chromosomal gene. Admittedly, however, the vitamin B12 assay is a somewhat insensitive indicator of relative TonB function in E. coli, inasmuch as the assay requires only modest TonB activity for growth (17). Thus, while mutations appearing inactive can be viewed so with confidence, those appearing active may well be substantially compromised. Indeed, by using a second E. coli tonB strain and growth under conditions of iron restriction as an indicator of TonB1 activity, mutations at Pro265, Gln293, and Val294 in TonB1 markedly compromised function (Table 2), even though the vitamin B12 assay failed to reflect this. In general, however, both assays were in agreement vis-á-vis TonB1 activity (Tables 2 and 3). Interestingly, Pro265 is highly conserved in TonB proteins (Fig. 5), although apparently dispensable for TonB1 function in P. aeruginosa, at least as far as its contribution to pyoverdine-mediated iron acquisition is concerned. A common theme that emerges is that mutations differentially affect TonB1 activity in its native versus a heterologous host. While this may well reflect different requirements for TonB1 function in these organisms and that residues His98, Pro265, Gln293, and Val294 are specifically required in E. coli, it is important to note that TonB1 is intrinsically less able to complement the tonB phenotypes in E. coli than is, for example, TonBEc (60), and thus changes that even modestly impact function may appear to compromise activity. Still, given the ability of the vitamin B12 assay to detect even minimal TonB activity it is likely that, for example, the His98Gly and Glu274Ala/Asp304Asn TonB1 variants are truly inactive in E. coli though active in P. aeruginosa. The fact that numerous TonB1-TonBEc chimeras are active in E. coli but not in P. aeruginosa also suggests that there are certainly differences vis-á-vis the organismal requirements for TonB1 function. Whether this simply reflects the need to interact with different receptors in these two organisms (see above) remains to be seen.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Postle for providing the anti-TonBEc monoclonal antibodies, R. Kadner for providing E. coli RK5015, and V. Braun for providing plasmid pCG752.

This work was supported by an operating grant to K.P. from the Medical Research Council of Canada (now the Canadian Institutes for Health Research). K.P. is a Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CCFF) Scholar. Q.Z. holds a CCFF studentship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmer, B. M. M., M. G. Thomas, R. A. Larsen, and K. Postle. 1995. Characterization of the exbBD operon of Escherichia coli and the role of ExbB and ExbD in TonB function and stability. J. Bacteriol. 177:4742-4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ankenbauer, R. G., and H. N. Quan. 1994. FptA, the Fe(III)-pyochelin receptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a phenolate siderophore receptor homologous to hydroxamate siderophore receptors. J. Bacteriol. 176:307-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anton, M., and K. J. Heller. 1991. Functional analysis of a C-terminally altered TonB protein of Escherichia coli. Gene 105:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1992. Short protocols in molecular biology, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 5.Bayer, P., and S. Harjes. 2001. TonB: a mediator of iron uptake in bacteria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:472. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bell, P. E., C. D. Nau, J. T. Brown, J. Konisky, and R. J. Kadner. 1990. Genetic suppression demonstrates interaction of TonB protein with outer membrane transport proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:3826-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos, C., D. Lorenzen, and V. Braun. 1998. Specific in vivo labeling of cell surface-exposed protein loops: reactive cysteines in the predicted gating loop mark a ferrichrome binding site and a ligand-induced conformational change of the Escherichia coli FhuA protein. J. Bacteriol. 180:605-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, M., H. Killmann, and V. Braun. 1999. The beta-barrel domain of FhuA Δ5-160 is sufficient for TonB-dependent FhuA activities of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1037-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun, V., S. Gaisser, C. Herrmann, K. Kampfenel, H. Killmann, and I. Traub. 1996. Energy-coupled transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: ExbB binds ExbD and TonB in vitro, and leucine 132 in the periplasmic region and aspartate 25 in the transmembrane region are important for ExbD activity. J. Bacteriol. 178:2836-2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun, V., and H. Killmann. 1999. Bacterial solutions to the iron-supply problem. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruske, A. K., M. Anton, and K. J. Heller. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of the Klebsiella pneumoniae tonB gene and characterization of Escherichia coli-Klebsiella pneumoniae TonB hybrid proteins. Gene 131:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan, S. K., B. S. Smith, L. Venkatramani, D. Xia, L. Esser, M. Palnitkar, R. Chakraborty, D. van der Helm, and J. Deisenhofer. 1999. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cadieux, N., and R. J. Kadner. 1999. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals an interaction site between energy-coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10673-10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang, C., A. Mooser, A. Pluckthun, and A. Wlodawer. 2001. Crystal structure of the dimeric C-terminal domain of TonB reveals a novel fold. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27535-27540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean, C. R., and K. Poole. 1993. Cloning and characterization of the ferric enterobactin receptor gene (pfeA) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 175:317-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dennis, J. J., E. R. Lafontaine, and P. A. Sokol. 1996. Identification and characterization of the tolQRA genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 178:7059-7068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.di Girolamo, P. M., R. J. Kadner, and C. Bradbeer. 1971. Isolation of vitamin B12 transport mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 106:751-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eick-Helmerich, K., and V. Braun. 1989. Import of biopolymers into Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequences of the exbB and exbD genes are homologous to those of the tolQ and tolR genes. J. Bacteriol. 171:5117-5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson, A. D., E. Hofmann, J. W. Coulton, K. Deiderichs, and W. Welte. 1998. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science 282:2215-2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer, E., K. Günter, and V. Braun. 1989. Involvement of ExbB and TonB in transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: phenotypic complementation of exbB mutants by overexpressed tonB and physical stabilization of TonB by ExbB. J. Bacteriol. 171:5127-5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray-Owen, S. D., and A. B. Schryvers. 1996. Bacterial transferrin and lactoferrin receptors. Trends Microbiol. 4:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Günter, K., and V. Braun. 1990. In vivo evidence for FhuA outer membrane receptor interaction with the TonB inner membrane protein of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 274:85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannavy, K., G. C. Barr, C. J. Dorman, J. Adamson, L. R. Mazengera, M. P. Gallagher, J. S. Evans, B. A. Levine, I. P. Trayer, and C. F. Higgins. 1990. TonB protein of Salmonella typhimurium: a model for signal transduction between membranes. J. Mol. Biol. 216:897-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hantke, K., and L. Zimmermann. 1981. The importance of the exbB gene for vitamin B12 and ferric iron transport. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 12:31-35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harle, C., I. Kim, A. Angerer, and V. Braun. 1995. Signal transfer through three compartments: transcription initiation of the Escherichia coli ferric citrate transport system from the cell surface. EMBO J. 14:1430-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heller, K. J., R. J. Kadner, and K. Günther. 1988. Suppression of the btuB451 mutation by mutations in the tonB gene suggests a direct interaction between TonB and TonB-dependent receptor proteins in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Gene 64:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgs, P. I., P. S. Myers, and K. Postle. 1998. Interactions in the TonB-dependent energy transduction complex: ExbB and ExbD form homomultimers. J. Bacteriol. 180:6031-6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohnadel, D., D. Haas, and J.-M. Meyer. 1986. Mapping of mutations affecting pyoverdine production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 36:195-199. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard, S. P., C. Herrmann, C. W. Stratilo, and V. Braun. 2001. In vivo synthesis of the periplasmic domain of TonB inhibits transport through the FecA and FhuA iron siderophore transporters of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5885-5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes, M. J., and D. W. Andrews. 1996. Creation of deletion, insertion and substitution mutations using a single pair of primers and PCR. BioTechniques 20:188-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaskula, J. C., T. E. Letain, S. K. Roof, J. T. Skare, and K. Postle. 1994. Role of the TonB amino terminus in energy transduction between membranes. J. Bacteriol. 176:2326-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang, X., M. A. Payne, Z. Cao, S. B. Foster, J. B. Feix, S. M. C. Newton, and P. E. Klebba. 1997. Ligand-specific opening of a gated-porin channel in the outer membrane of living bacteria. Science 276:1261-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadner, R. J. 1990. Vitamin B12 transport in Escherichia coli: energy coupling between membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2027-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kampfenkel, K., and V. Braun. 1992. Membrane topology of the Escherichia coli ExbD protein. J. Bacteriol. 174:5485-5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kampfenkel, K., and V. Braun. 1993. Topology of the ExbB protein in the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:6050-6057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson, M., K. Hannavy, and C. F. Higgins. 1993. A sequence-specific function for the N-terminal signal-like sequence of the TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 8:379-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlsson, M., K. Hannavy, and C. F. Higgins. 1993. ExbB acts as a chaperone-like protein to stabilize TonB in the cytoplasm. Mol. Microbiol. 8:389-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Killmann, H., R. Benz, and V. Braun. 1993. Conversion of the FhuA transport protein into a diffusion channel through the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 12:3007-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Killmann, H., M. Braun, C. Herrmann, and V. Braun. 2001. FhuA barrel-cork hybrids are active transporters and receptors. J. Bacteriol. 183:3476-3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsen, R. A., D. Foster-Hartnett, M. A. McIntosh, and K. Postle. 1997. Regions of Escherichia coli TonB and FepA proteins essential for in vivo physical interactions. J. Bacteriol. 179:3213-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsen, R. A., P. S. Myers, J. T. Skare, C. L. Seachord, R. P. Darveau, and K. Postle. 1996. Identification of TonB homologs in the family Enterobacteriaceae and evidence for conservation of TonB-dependent energy transduction complexes. J. Bacteriol. 178:1363-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larsen, R. A., M. G. Thomas, and K. Postle. 1999. Protonmotive force, ExbB and ligand-bound FepA drive conformational changes in TonB. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1809-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsen, R. A., M. G. Thomas, G. E. Wood, and K. Postle. 1994. Partial suppression of an Escherichia coli TonB transmembrane mutation (V17) by a missense mutation in ExbB. Mol. Microbiol. 13:627-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larsen, R. A., G. E. Wood, and K. Postle. 1993. The conserved proline-rich motif is not essential for energy transduction by Escherichia coli TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 10:943-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Letain, T. E., and K. Postle. 1997. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 24:271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, J., J. M. Rutz, P. E. Klebba, and J. B. Feix. 1994. A site-directed spin-labeling study of ligand-induced conformational change in the ferric enterobactin receptor, FepA. Biochemistry 33:13274-13283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Locher, K. P., B. Rees, R. Koebnik, A. Mitschler, L. Moulinier, J. P. Rosenbusch, and D. Moras. 1998. Transmembrane signaling across the ligand-gated FhuA receptor: crystal structures of free and ferrichrome-bound states reveal allosteric changes. Cell 95:771-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Locher, K. P., and J. P. Rosenbusch. 1996. Modeling ligand-gated receptor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1448-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lugtenberg, B., J. Mrijers, R. Peters, P. van der Hoek, and L. van Alphen. 1975. Electrophoretic resolution of the major outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli K12 into four bands. FEBS Lett. 58:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundrigan, M. D., and R. J. Kadner. 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the ferrienterochelin receptor FepA in Escherichia coli: homology among outer membrane receptors that interact with TonB. J. Biol. Chem. 261:10797-10801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merianos, H. J., N. Cadieux, C. H. Lin, R. J. Kadner, and D. S. Cafiso. 2000. Substrate-induced exposure of an energy-coupling motif of a membrane transporter. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moeck, G. S., and J. W. Coulton. 1998. TonB-dependent iron acquisition: mechanisms of siderophore-mediated active transport. Mol. Microbiol. 28:675-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moeck, G. S., J. W. Coulton, and K. Postele. 1997. Cell envelope signalling in Escherichia coli: ligand binding to the ferrichrome-iron receptor FhuA promotes interaction with the energy-transducing protein TonB. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28391-28397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moeck, G. S., and L. Letellier. 2001. Characterization of in vitro interactions between a truncated TonB protein from Escherichia coli and the outer membrane receptors FhuA and FepA. J. Bacteriol. 183:2755-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moeck, G. S., P. Tawa, H. Xiang, A. A. Ismail, J. L. Turnbull, and J. W. Coulton. 1996. Ligand-induced conformational change in the ferrichrome-iron receptor of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 22:459-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morales, V. M., A. Backman, and M. Bagdasarian. 1991. A series of wide-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohman, D. E., J. C. Sadoff, and B. H. Iglewski. 1980. ToxA-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA103: isolation and characterization. Infect. Immun. 28:899-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poole, K., S. Neshat, and D. Heinrichs. 1991. Pyoverdine-mediated iron transport in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement of a high-molecular-mass outer membrane protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 78:1-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poole, K., S. Neshat, K. Krebes, and D. E. Heinrichs. 1993. Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of the ferripyoverdine receptor gene fpvA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 175:4597-4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poole, K., Q. Zhao, S. Neshat, D. E. Heinrichs, and C. R. Dean. 1996. The tonB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a novel TonB protein. Microbiology 142:1449-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Postle, K., and J. T. Skare. 1988. Escherichia coli TonB protein is exported from the cytoplasm without proteolytic cleavage of its amino terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11000-11007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roof, S. K., J. D. Allard, K. P. Bertrand, and K. Postle. 1991. Analysis of Escherichia coli TonB topology by use of PhoA fusions. J. Bacteriol. 173:5554-5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rutz, J. M., J. Liu, J. A. Lyons, J. Goranson, S. K. Armstrong, M. McIntosh, J. B. Feix, and P. E. Klebba. 1992. Formation of a gated channel by a ligand-specific transport protein in the bacterial outer membrane. Science 258:471-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 65.Schleif, R. 1987. The l-arabinose operon, p. 1473-1481. In F. Neidhardt, J. Ingraham, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: molecular and cellular biology, vol. 2. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schöffler, H., and V. Braun. 1989. Transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12 via the FhuA receptor is regulated by the TonB protein of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol. Gen. Genet. 217:378-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schramm, E., J. Mende, V. Braun, and R. M. Kamp. 1987. Nucleotide sequence of the colicin B activity gene cba: consensus pentapeptide among TonB-dependent colicins and receptors. J. Bacteriol. 169:3350-3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Skare, J. T., B. M. M. Ahmer, C. L. Seachord, R. P. Darveau, and K. Postle. 1993. Energy transduction between membranes. TonB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein, can be chemically cross-linked in vivo to the outer membrane receptor FepA. J. Biol. Chem. 268:16302-16308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skare, J. T., and K. Postle. 1991. Evidence for a TonB-dependent energy transduction complex in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2883-2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Srikumar, R., T. Kon, N. Gotoh, and K. Poole. 1998. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug efflux pumps MexA-MexB-OprM and MexC-MexD-OprJ in a multidrug-sensitive Escherichia coli strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:65-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. W. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Traub, I., S. Gaisser, and V. Braun. 1993. Activity domains of the TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol. 8:409-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wandersman, C., and I. Stojiljkovic. 2000. Bacterial heme sources: the role of heme, hemoprotein receptors and hemophores. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao, Q., X.-Z. Li, R. Srikumar, and K. Poole. 1998. Contribution of outer membrane efflux protein OprM to antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independent of MexAB. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1682-1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao, Q., X.-Z. Li, A. Mistry, R. Srikumar, L. Zhang, O. Lomovskaya, and K. Poole. 1998. Influence of the TonB energy-coupling protein on efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2225-2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Zhao, Q., and K. Poole. 2000. A second tonB gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is linked to the exbB and exbD genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]