Abstract

A lantibiotic gene cluster was identified in Bacillus subtilis A1/3 showing a high degree of homology to the subtilin gene cluster and occupying the same genetic locus as the spa genes in B. subtilis ATCC 6633. The gene cluster exhibits diversity with respect to duplication of two subtilin-like genes which are separated by a sequence similar to a portion of a lanC gene. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analyses of B. subtilis A1/3 culture extracts confirmed the presence of two lantibiotic-like peptides, ericin S (3,442 Da) and ericin A (2,986 Da). Disruption of the lanB-homologous gene eriB resulted in loss of production of both peptides, demonstrating that they are processed in an eriB-dependent manner. Although precursors of ericins S and A show only 75% of identity, the matured lantibiotic-like peptides reveal highly similar physical properties; separation was only achieved after multistep, reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Based on Edman and peptidase degradation in combination with MALDI-TOF MS, for ericin S a subtilin-like, lanthionine-bridging pattern is supposed. For ericin A two C-terminal rings are different from the lanthionine pattern of subtilin. Due to only four amino acid exchanges, ericin S and subtilin revealed similar antibiotic activities as well as similar properties in response to heat and protease treatment. For ericin A only minor antibiotic activity was found.

Lantibiotics are amphiphilic peptide antibiotics of bacterial origin and are nearly exclusively produced by gram-positive bacteria. They contain unusual constituents like nonproteinogenic didehydroamino acids and lanthionines (49; for reviews, see references 16, 30, 47, and 51). Out of the about 26 known lantibiotics, the nisins (A and Z) of Lactococcus lactis cheese starter organisms (6, 15) are the best-studied members which are also of commercial value (5, 14, 21, 31, 33, 41). Subtilin was the first lantibiotic isolated from Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (22; for review, see reference 16). A variant of subtilin (subtilin B) was found to have reduced antibiotic activity due to posttranslational succinylation of the amino group of the N-terminal tryptophan residue (7). Sublancin from B. subtilis 168 is quite different and contains a single lanthionine linkage and two disulfide bridges (43). A relative small lantibiotic, mersacidin of Bacillus sp., shows unusual properties with respect to bridging, amphiphilic character, and C-terminal modification (30). Lantibiotics are ribosomally synthesized as precursor peptides consisting of an N-terminal leader and the propeptide sequence. The latter becomes posttranslationally modified by dehydration and thioether formation (49). The biochemistry of these modifications is still unknown but is associated in one group of lantibiotics with proteins LanB and LanC (24, 35) and in a second group with LanM (16, 46; for review, see reference 47). A multimeric enzyme complex consisting of LanBTC was demonstrated for subtilin and nisin to be membrane associated and to catalyze modification and transport (32, 50).

The B. subtilis strain A1/3 attracted our attention due to a broad spectrum of inhibitory activities against fungi and phytoviruses (28), as well as against diverse bacteria. Notable among these is the causative agent of tomato bacterial canker, Clavibacter michiganensis (20). In this paper we report the discovery of a lantibiotic gene cluster of B. subtilis A1/3, which shows conserved character to subtilin genes but encodes two distinct lantibiotic peptides, ericin S and ericin A. Both ericins were isolated from culture supernatants of B. subtilis A1/3, studied by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), peptidase digestion, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The complete ericin gene cluster has been sequenced. Mutant studies indicated that both peptides are processed by the LanB homologue EriB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The original B. subtilis A1/3 (20, 28) contained at least two plasmids. A derivative GB709 of strain A1/3 was cured from plasmid DNA by repeated protoplasting and protoplast regeneration (8) and was used throughout these studies synonymously to A1/3, as it exhibited no detectable phenotypic differences from the parental strain. For antibiotic activity tests the following were used: B. subtilis strains DSM 402 (Spizizen strain 168), 1088 (B. subtilis [natto]), 2277 (B. globii, B. subtilis subsp. niger), 6405 (mutant of strain W23), and 3256, as well as strain 3258; B. subtilis ATCC 6633; Bacillus brevis ATCC 7577; Bacillus polymyxa ATCC 842; Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579; Bacillus circulans ATCC 9966; Bacillus firmus ATCC 14575; Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ATCC 15841; Bacillus pumilus (B55; our collection); Bacillus sphaericus ATCC 14577; Bacillus megaterium PV361 (56); Staphylococcus aureus; Lactococcus lactis strains IL-1403 (10) and 6F3 (31); Staphylococcus carnosus TM300 (19); Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341; C. michiganensis subsp. michiganensis (our collection); and Lactobacillus sake LTH673 (53).

Escherichia coli, Bacillus, Micrococcus, and S. aureus cultures were propagated in TBY medium (0.8% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl). The solid medium for cultivation of E. coli and B. subtilis was TBY agar (TBY medium solidified with 1.5% agar). S. carnosus was grown in TBY medium with 2% glucose; C. michiganensis, Lactococcus, and Lactobacillus cultures were grown in SOB medium (25) supplemented with 2% glucose. For high production of antibiotics B. subtilis A1/3 was grown in ACS medium (54). Cultures were usually grown at 30°C on a rotating incubator. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (micrograms/milliliter): for B. subtilis, erythromycin, 5; and for E. coli, ampicillin, 100; and erythromycin, 70. The plasmids used are shown in Table 1. Recombinant plasmids were amplified in E. coli XL1-blue (Stratagene) and B. subtilis GSB26 (26), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids

| Plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript SK(+) | Ampr | Stratagene |

| pGEM-T | Ampr | Promega |

| pSB2.3 | Ampr, pBluescript SK(+) containing a 2.3-kb PCR fragment of the B. subtilis A1/3 eriB gene | This study |

| pE194ts | Eryr | 27 |

| pESB1 | pE194 with 1.7-kb EcoRV eriB subfragment of pSB2.3 | This study |

DNA technology.

General molecular cloning techniques and DNA detection assays were carried out essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (54) and Ausubel et al. (1). Total DNA of B. subtilis was isolated as described by Cutting and Horn (13). Plasmid DNA was purified using a plasmid isolation kit (Qiagen), except that B. subtilis cells were incubated in lyses buffer with 4 mg of egg white lysozyme per ml for 15 to 30 min. Enzymes were used as recommended by the supplier. PCR or restriction DNA fragments were isolated from agarose gels and purified using Qiaex (Qiagen). Competent cells of E. coli were prepared and transformed following the procedure of Hanahan (25). B. subtilis was transformed with plasmid DNA using competent cells as described by Gryczan et al. (23) or with DNA ligation mixes using the protoplast transformation protocol of Chang and Cohen (8).

PCR amplification, sequencing, and sequence handling.

Sequencing by primer walking was achieved directly from PCR-generated DNA fragments following the procedures described previously (45). DNA fragments were obtained by long-range PCR (3, 9) or by applying inverse long-range PCR techniques, using the GeneAmp XL-PCR kit with rTth polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). The PCR primers used are listed in Table 2. Other PCRs were performed using Taq DNA polymerase and reaction conditions as recommended by the supplier (Boehringer). PCR was run in a ThermoCycler GeneAmp 2400 (Perkin-Elmer) using the following protocol: 100 to 300 ng of genomic DNA, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), the required concentration of each primer, and 1.25 U of DNA polymerase. The reaction mix was dispensed as 25-μl aliquots in 0.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and was overlaid with mineral oil. The samples were amplified after incubation at 94°C (5 min), followed by 30 cycles at 94°C (30 s), 55°C (30 s), and 72°C (1 min) for amplification of small (0.5-kb) and at 72°C (3 min) for amplification of larger (3- or 4-kb) DNA fragments, respectively, followed by 1 cycle of 72°C (5 min). The nucleotide sequence was determined on both strands by using either an Applied Biosystems 373S sequencer (Scientific Research and Development, Oberursel/Frankfurt, Germany) or A.L.F. DNA Sequencer (Pharmacia). The sequence data were evaluated on the basis of sequence homology to GenBank entities using BLASTN and BLASTX and were analyzed using the open reading frame finder (18) and annotation program of Sequin Application Version 3.00 (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primersa

| Primer | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SB5 | GAWKNACWCCWTWTGG | Upstream primer for eriB |

| SB6 | CCRCCATATCSWTMTRYYTC | Downstream primer for eriB |

| SB93 | ATTATTTTGGCGGCCGCCATCCCGACC | Upstream primer for opuBD |

| SB94 | TCGATTAGCGGCCGCTCATCCAATTCAATGG | Downstream primer for yvaO |

Sequences are shown 5′ to 3′; R, S, K, W, M, R, and Y correspond to A/G, G/T, G/C, A/T, A/C, A/G, and A/T/G/C, respectively.

Antibiotic production and assays.

For antibiotic production, stationary cultures in ACS medium of respective strains were diluted 1:50 into 200 ml of fresh ACS medium in 1l-Erlenmeyer flasks and were shaken at either 30 or 37°C.. Samples were taken periodically and centrifuged, and the culture supernatant was either directly used for antibiotic assays or for peptide purification. Substances (i.e., subtilin and ericin) were dissolved in water (100 μg per ml) and adjusted to pH 2 by HCl.

Purification of lantibiotic-like peptides.

The lantibiotic-like peptides ericins A and S were purified in an analytical scale by three reversed-phase HPLC steps. Fifty milliliters of culture supernatant of ACS cultures grown for 20 to 24 h at 37°C was harvested by filtration through an 50-μm-pore-size membrane filter, loaded onto a C18-Lichrospher column (20 × 200 mm; particle size, 10 mm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and separated by linear gradients of acetonitrile. Active fractions were lyophilized and separated two times using an analytical C18-ODS Hypersil column (2 × 250 mm; particle size, 5 μm; Maisch, Ammerbuch, Germany). The eluent system for all HPLC steps was as follows: eluent A, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and 10% acetonitrile in H2O (vol/vol/vol); and eluent B, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile (vol/vol). The peptides were detected measuring the absorbance at 280 or 214 nm.

Agar diffusion assay.

In general 10 μl of the inhibitory substances was poured into wells (6-mm diameter) of TBY agar (40 ml, 1.5% [wt/vol]) in plates (12 by 12 cm square) previously seeded with growing cells of the test strain into 10 ml of TBY (soft) agar (0.8%). The cell density of each test strain in the soft agar was empirically adjusted (using 0.3 to 0.8 ml of growing cultures at an optical density of 600 nm of 0.5) to yield optimal results. Plates were placed at 4°C for 4 to 6 h to allow diffusion of the substances into the agar, and their contents were subsequently incubated for 12 to 18 h at 30°C. The diameter of the inhibition zones was determined. The values from at least three repetitions were averaged.

MALDI-TOF MS.

Delayed extraction-MALDI-TOF mass spectra were recorded on a Voyager-RP-delayed extraction instrument (Per Septive Biosystems) using a 337-nm nitrogen laser for desorption and ionization. All experiments were carried out with the reflector positive ion mode. The total acceleration voltage was 20 kV, and 11.6 kV was used on the first grid. The delay time was 250 ns. One-milliliter aliquots of culture supernatants were extracted with 1-butanol (200 μl), and 100 μl of the butanolic phase was dried in a rotator evaporator. Extracted peptides were dissolved in 20 μl of solvent A (70% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water [vol/vol/vol]). Part of the samples (0.7 μl) was mixed directly on the target with 0.7 μl of matrix (20 μg of α-cyano-β-hydroxycinnamic acid/μl in solvent A). Between 100 and 200 single scans were accumulated for each mass spectrum.

Protease, peptidase digestion, and amino acid sequencing.

Aliquots (5 μl) of reversed-phase HPLC-purified ericins containing 100 μg per ml in H2O were diluted in a total volume of 20 μl of H2O containing in parallel 100, 200, and 300 μg per ml of the proteases pronase E, proteinase K, subtilisin, pepsin, bromelain, and trypsin. Samples were treated for 1 h at 37°C. The residual antibiotic activities were assayed by the agar diffusion assay (see above) using the C. michiganensis strain. Control samples were made with equal volumes containing either the protease (300 μg/ml) or the antibiotic and were incubated for 1 h either at 37°C or on ice, respectively. Part of the ericin fraction (0.2 μg) was incubated in 2 μl of 50 mM ammonium carbonate buffer (pH 7.2) with 0.05 μg of either aminopeptidase M or carboxypeptidase B. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C the reaction mixture was analyzed by MALDI-TOF (MS). For N-terminal amino acid sequencing, the ericin fraction was subjected to Edman degradation using a model LF 3400 gas phase sequencer (Beckman), followed by HPLC of the phenyl thiohydantoin amino acids.

Temperature stability.

Five microliters of a solution of reversed-phase HPLC-purified subtilin or ericin S or A (100 μg per ml of H2O, adjusted to pH 2.0 by HCl) was diluted in a total volume of 20 μl of H2O and was heated for 30, 60, or 90 min in a water bath or left (for 90 min) on ice for a control. The residual inhibitory activity of the substances was assayed by the agar diffusion assay with C. michiganensis.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to GenBank under accession number AF233755.

RESULTS

B. subtilis A1/3 produces two lantibiotic-like peptides.

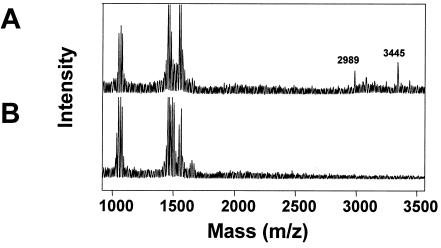

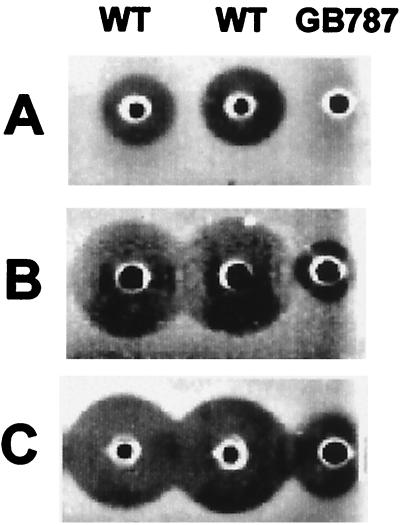

A broad spectrum of antibiotics are produced and excreted by B. subtilis A1/3 or by its cured derivative GB709, especially when grown in ACS medium (data not shown). In order to characterize them, butanolic extracts of culture supernatants were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. Several peak clusters with m/z values below 1,600 were attributed to the presence of different lipopeptide antibiotics (39, 52). As indicated in Fig. 1, several signals appeared at m/z above 2,900 with most prominent signals where m/z = 2,989 and 3,445. Both the antibiotic activity spectrum as well as the appearance of molecules with masses in the range of 3 kDa implied the presence of lantibiotic-like peptides and prompted us to look for a corresponding lantibiotic gene cluster. To identify such a cluster, we designed oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) according to conserved sequence motifs of LanB proteins (4, 51). A 2.3-kb DNA fragment was PCR amplified from B. subtilis A1/3 chromosomal DNA, cloned onto plasmid pSB2.3, and sequenced. The DNA was found to encode a LanB-like protein sequence. A lanB disruption mutant was constructed by cloning of an internal EcoRV subfragment of the pSB2.3 DNA insert into the XbaI site of plasmid pE194. The resulting plasmid pESB1 was transformed into strain GB709 at 30°C, and chromosomal integration was achieved by selecting for erythromycin resistance after cultivation at 52°C (12). Proper integration of pESB1 DNA was verified by Southern hybridization using the EcoRV subfragment as probe. The appearance of new hybridizing fragments in mutant GB787 (lanB::pESB1; data not shown) coincided with a major loss of an antibiotic activity against the test bacteria, notably against C. michiganensis (Fig. 2), as well as with the loss of the production of the molecules at m/z 2,989 and 3,345 (Fig. 1). These observations supported the proposal that B. subtilis A1/3 produces two lantibiotic-like peptides and that both are processed in a LanB-dependent manner.

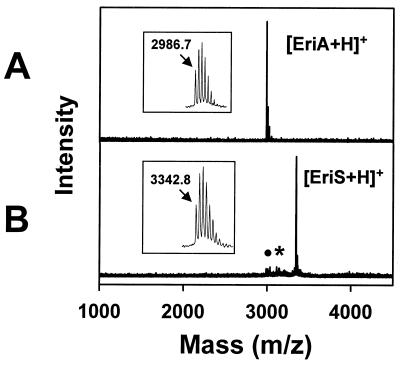

FIG. 1.

Positive-mode DE-MALDI-TOF mass spectra of butanolic extracts from B. subtilis A1/3 culture supernatants of wild-type (A) and mutant GB787 (lanB::pESB1) (B). Peak clusters at m/z 1050 to 1150 and 1450 to 1600 are in the range of cyclic lipopeptides. Signals observed at higher molecular masses (m/z 2989 and 3445) were postulated to be lantibiotic-like peptides because they were not found in the culture of a mutant lacking the lanB-type gene.

FIG. 2.

Antibiotic activity of B. subtilis A1/3 wild type (WT) and of mutant strain GB787 (lanB::pESB1). Thirty-microliter aliquots of the sterilized supernatants taken from 48 h-cultures were tested for growth inhibition of S. carnosus (A), C. michiganensis (B), and M. luteus (C).

Cloning and sequence analysis.

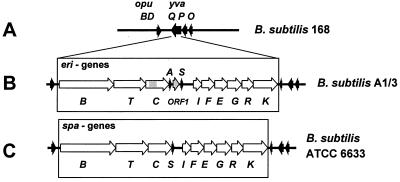

Starting from the PCR-amplified lanB sequence, we used the primer-walking method to sequence the surrounding DNA region containing the putative lantibiotic gene cluster of B. subtilis A1/3. A DNA region of 14.15 kb was sequenced and found to contain 12 open reading frames with striking similarity to the spa genes of B. subtilis ATCC 6633, with respect to nucleotide sequence as well as to the overall gene order (Fig. 3). As suggested from MALDI-TOF MS analyses, two subtilin-like open reading frames, eriA and eriS, were detected, comprising 159 and 168 nucleotides (nt) with 53 and 56 codons, respectively. The two gene copies are located between the lanC- and lanI-like genes and are separated by an additional open reading frame, orf1 (354 nt). Moreover, orf1 contains 333 nt of perfect identity to a portion of the upstream lanC-like gene of this gene cluster. Hence, at least two duplication events within the lan gene cluster of B. subtilis A1/3 likely created another copy of a subtilin-like gene and orf1 (Fig. 3). Otherwise, the conserved character of the gene cluster also concerns the overall gene order and gene overlaps. Consequently, the following gene order was concluded: eriBTC to eriA orf1 eriS to eriIFEG to eriRK (Fig. 3). Several open reading frames, e.g., for eriB-eriT, eriT-eriC, and eriI-eriF, as well as eriR-eriK, overlap by 7, 23, 24, and 25 nt, respectively. As indicated in Fig. 3, within the nucleotide sequence upstream of eriB, significant identities to the opuBD gene of B. subtilis 168 were observed (38). Moreover, analysis of the DNA upstream from eriK gene revealed three short open reading frames which were already found in the B. subtilis subtilin producer at the right border of the spaK gene (36) and which have putative counterparts (yvaQPO) in the B. subtilis 168 genome downstream of opuBD. These findings showed experimental evidence for a conserved genomic position of the eri-spa gene cluster in the corresponding lantibiotic producer strains between opuBD and yvaQPO of the B. subtilis 168 standard genome map.

FIG. 3.

(A) Map of the opuBD-yvaQPO region of B. subtilis strains 168. Arrows indicate open reading frames deduced by the B. subtilis genome project (38). In the ericin- and subtilin-producing strains, the greater part of the yvaQ gene is replaced by a lan gene cluster. (B) The eri gene cluster of B. subtilis A1/3 comprises 12 genes and about 12.5 kb (GenBank accession no. AF233755). Ericin A- and S-encoding genes eriA and eriS are separated by orf1, which exhibits 96% identity to a gray portion of eriC. (C) The spa gene cluster of B. subtilis ATCC 6633 comprises 10 genes and about 12 kb. The gene order spaIFEG is given according to the revised sequence of spa genes (EMBL Gene Bank accession no. U09819).

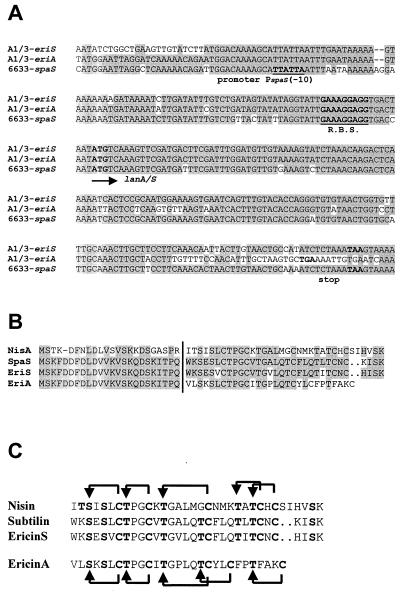

As summarized in Table 3, a high degree of identity between Eri and Spa proteins was determined also on the protein level. Here identity values between 71 and 94% were calculated. The two prepropeptides deduced from the sequence of the eriA and eriS genes revealed identical N-terminal leader sequences but also revealed variation in their propeptide portion due to changes or by deletion of amino acids (Fig. 4); the matured peptides were named ericin A and ericin S. Compared to the subtilin precursor, the precursor peptides of ericin A and ericin S contain either 75 or 92 percent identical amino acid residues.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Eri and Spa proteins

| Lan protein | Size (no. of amino acids) for:

|

Identity (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eri | Spa | ||

| LanB | 1,030 | 1,030 | 83 |

| LanT | 614 | 614 | 94 |

| LanC | 441 | 441 | 80 |

| LanAb | 53 | 75c | |

| Orf1 | 118 | 77/96d | |

| LanSb | 56 | 56 | 92c |

| LanI | 168 | 165 | 77 |

| LanF | 238 | 238 | 92 |

| LanE | 251 | 251 | 71 |

| LanG | 256 | 256 | 72 |

| LanR | 220 | 220 | 90 |

| LanK | 439 | 441 | 81 |

Identity values were calculated with Blast 2 sequences at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

EriA and EriS exhibit 75% identity.

Identity to SpaS.

Identity of orf1 to a 118-amino-acid intergenic region of SpaC and EriC (positions 27 to 144), respectively.

FIG. 4.

(A) Alignment of eriA and -S and spaS of B. subtilis A1/3 and 6633. The promoter −10 box of spaS (T. Stein, S. Borchert, P. Kiesau, S. Heinzmann, S. Klöß, C. Klein, M. Helfrich, and K.-D. Entian, unpublished data), the ribosome binding site (R.B.S.), translation initiation (marked by an arrow), and stop codons are indicated in boldface. Identical nucleotides in two sequences are shaded. (B) Alignment of the deduced ericin A and ericin S precursor peptides EriA and -S with precursor peptides of subtilin (SpaS) and nisin (NisA). Conserved residues are shaded, and the cleavage site of the processing protease is symbolized by a vertical line, separating N-terminal leader peptides from C-terminal propeptides. (C) Alignment of matured lantibiotics. Thioether bridging of subtilin and nisin and proposed bridges of ericin S and ericin A are shown. Posttranslational modified residues of the lantibiotics are given in boldface.

Purification of ericins A and S.

The two lantibiotic-like peptides were isolated from B. subtilis A1/3 cultures by multistep reversed-phase HPLC and were monitored by antimicrobial assays and offline MALDI-TOF MS analyses. Filtrates of ACS cultures were first separated on a semipreparative column. Both lantibiotic-like peptides eluted at 40% acetonitrile; however, they were poorly separable under the conditions analyzed. Separation of both ericin peptides was achieved by two further HPLC steps using analytical reversed-phase columns. The grade of purification was estimated by analyzing aliquots of the purified peptide fractions by MALDI-TOF MS. As indicated in Fig. 5, for ericin A, a purity of more than 95% was achieved. Most important, no contamination of ericin S was detectable within the mass spectrum. For ericin S, an enrichment over 80% was achieved. However, due to the similar chromatographic behavior of both ericins, a slight contamination of ericin A was present, even after further separation steps. The molecular masses of ericin A (m/z 2,986.7) and S (m/z 3,342.8) were determined from their monoisotopic signals (Fig. 5). The minor peak within the ericin S fraction at m/z 3142 could be interpreted as the removal of pyruvyl-lysine (199 Da).

FIG. 5.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of reversed-phase HPLC-purified ericins A and S. (A) The most prominent peak corresponds to protonated ericin A; a molecular mass of 2,986.7 Da was determined using the monoisotopic signal (inset). (B) The prominent signal corresponds to the protonated species of ericin S; a molecular mass of 3,342.8 Da was determined using the monoisotopic signal (inset). Two minor signals can be attributed to traces of ericin A (black dot) and degraded ericin S species at m/z 3142.2 (star), from which pyruvyl-lysine was removed. Protonated ericin clusters were measured with a resolution of about 12,500.

Molecular properties of ericin(s).

As indicated in Fig. 4, ericin A and ericin S exhibit a high degree of similarity to subtilin. The calculated molecular weights of the ericin peptides ([M + H]+ for ericin A, 3,094.5; and for ericin S, 3,486.6) are significantly higher than the measured values (2,986.7 and 3,342.8, respectively). The differences of 107.8 for ericin A and 143.8 for ericin S are in agreement with the abstraction of six and eight water molecules, respectively. Strikingly, this fits exactly with the number of serine and threonine residues of ericin A (six) and ericin S (eight), implying that all Ser/Thr residues of these molecules are in the dehydrated state or are part of lanthionine residues. Additionally, no alkylation of ericin A or S by iodoacetamide treatment could be observed (data not shown), supporting the hypothesis that no free cysteine residues are present and that the Cys residues, five in the case of ericin A and five in the case of ericin S, form thioether bridges to formerly dehydrated Ser/Thr residues. N-terminal sequence analyses by Edman degradation of ericin S resulted in the sequence W-K-X-E. Tryptophan and lysine in the first two sequencing steps are in agreement with the deduced N-terminal amino acids of ericin S. The observation of a blank (X) at position 3 might result from a lanthionine-bridged amino acid residue; the following glutamate fits with the sequence of ericin S. For further characterization of the N- and C-terminal amino acid residues of ericin S or A, the peptides were cleaved with aminopeptidase M or with carboxypeptidase B, respectively. After 2 h the reaction mixtures were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. For ericin S, aminopeptidase cleavage resulted in removal of 186 and 315 Da from the intact peptide, which exactly corresponds to the removal of W and WK from the N terminus. No further amino acids were removed, most likely because of the presence of a lanthionine ring at the third position of the N terminus. After carboxypeptidase B treatment, the signals at m/z 3214, 3146, and 3033 fit exactly with the removal of K, K-ΔA, and K-ΔA-I from the C-terminal end of ericin S, respectively, demonstrating also the abstraction of water from serine, resulting in the didehydroalanine residue (ΔA) at the penultimate position. Aminopeptidase M degradation of ericin A resulted in several peaks corresponding to removal of V (99 Da) and V-L (212 Da), indicating the degradation of both amino-terminal residues (Fig. 4). A strong hint for a modified C-terminal residue of ericin A was the stability of the peptide during carboxypeptidase B digestion (data not shown). The intensity of the signal for ericin A was not affected after 2 h of incubation, whereas ericin S was completely degraded.

Antibiotic properties of ericin S.

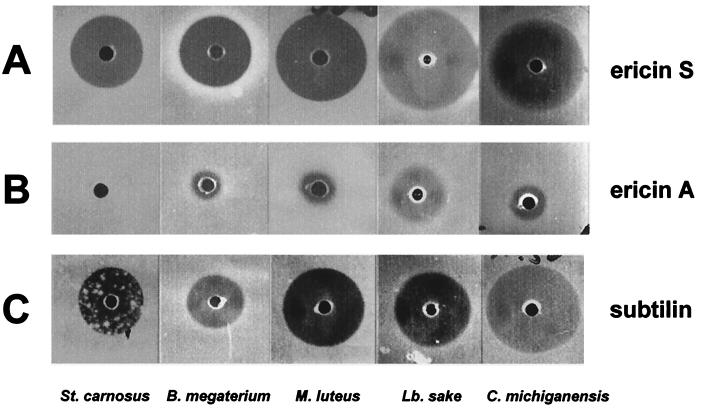

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the purified ericin S and ericin A fractions differed in their specific antibiotic activities. Ericin A displayed only slight antibiotic activities against strains with the highest sensitivities for ericin S (Fig. 6A and B). A quantitative assay indicated that those minor activities of ericin A coincided with the inhibition zone of a 100-fold-diluted ericin S sample (data not shown). It was therefore not excluded that the observed activities of ericin A are due to a contamination of ericin S traces within the ericin A preparation, which was not detectable by MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 5). Ericin S (Fig. 6A) showed activity similar to that of subtilin (Fig. 6C). Additionally, 20 different strains were evaluated for sensitivity to ericin S and subtilin (Table 4). All strains sensitive to ericin S were also sensitive to subtilin; however, B. firmus, B. polymyxa, and B. subtilis (natto), as well as B. subtilis strains DSM 3256 and DSM 3258, exhibited significantly higher sensitivities to subtilin. About half of the strains, including S. aureus and B. subtilis DSM 402 (Marburg strain), as well as the lantibiotic-producing strains ATCC 6633 and A1/3, were resistant to subtilin and ericin S.

FIG. 6.

Antibiotic activity of reversed-phase HPLC- purified ericin S (A), ericin A (B), and subtilin (C). An amount (0.4 μg) of purified peptides (in water, pH 2, with HCl) was poured per well and tested for growth inhibition of S. carnosus, B. megaterium, M. luteus, L. sake, and C. michiganensis. The inhibition zones are from one homologous series of indicator plates.

TABLE 4.

Antibiotic activity spectrum of ericin Sa in comparison to subtilin

| Test strain | Diam of inhibition zone (mm)b for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Ericin S | Subtilin | |

| B. alvei ATCC 6344 | 0 | 0 |

| B. amyloliquefaciens ATCC 15841 | 4 | 4.5 |

| B. brevis ATCC 7577 | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| B. cereus ATCC 14579 | 3.5 | 5 |

| B. circulans ATCC 9966 | 0 | 0 |

| B. firmus ATCC 14575 | 9.5 | 17 |

| B. polymyxa ATCC 842 | 5 | 9 |

| B. pumilus B55 | 0 | 0 |

| B. sphaericus ATCC 14577 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| B. subtilis A1/3 | 0 | 0 |

| B. subtilis ATCC 6633 | 0 | 0 |

| B. subtilis DSM 402 | 0 | 0 |

| B. subtilis (natto) DSM 1088 | 6 | 10.5 |

| B. subtilis (niger) DSM 2277 | 0 | 0 |

| B. subtilis DSM 3256 | 3 | 7 |

| B. subtilis DSM 3258 | 5 | 7 |

| B. subtilis DSM 6405 | 0 | 0 |

| L. lactis 6F3 | 0 | 0 |

| L. lactis IL-1403 | 8 | 6 |

| S. aureus | 0 | 0 |

Purified peptides (0.2 μg) (in water, pH 2, with HCl) were used. The ericin fraction contained a ratio of ericin S to ericin A of approximately 3:1. Therefore, the measured antibiotic activity is exclusively due to ericin S (Fig. 6 and the text).

The values from three repetitions were averaged. The diameter of the wells was subtracted. Standard errors were <20% for each given value.

Protease and heat stability.

The ericin S-ericin A peptide fraction was digested with several proteases, and residual activities were compared, whereby due to its antibiotic inefficiency (see above), any reaction with ericin A could be neglected. Subtilin in general was more stable against bromelain and subtilisin and in particular against proteinase K, while ericin S was more resistant against trypsin and pepsin. The two substances were likewise sensitive to pronase E (data not shown). At temperatures above 60°C, the antibiotically active ericin S was less stable and lost its antibiotic activity after 90 min at 100°C to about 80% (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We characterized two lantibiotic-like peptides, ericin A (2,986.7 Da) and ericin S (3,342.8 Da) produced by the B. subtilis strain A1/3 and sequenced the corresponding gene cluster. For ericin S only, antibiotic activities were observed against several gram-positive bacteria, which were similar to those of subtilin (Fig. 6; Table 4). For ericin A, however, only minor activities were found, which can be attributed to the presence of ericin S impurities.

Derived from conserved motifs of LanB proteins (4, 51), oligonucleotide primers were designed and used to amplify a specific DNA fragment from B. subtilis A1/3 genomic DNA. This fragment was used to construct a lanB DNA-specific disruption mutant which lost the ability to produce both ericin molecules (Fig. 1) and the antibiotic activities attributed to the ericin fraction (Fig. 2). These findings confirmed the involvement of the LanB (= EriB) protein in the biosynthesis of the two ericins. The eriB DNA was used to sequence a chromosomal region of about 14,150 nt by primer walking, establishing a lan-like gene cluster with 11 open reading frames: eriBTC to eriA, orf1, eriS, and eriIFEGRK (Fig. 3). The deduced proteins showed highest similarity (of 71 to 95%) to the Spa proteins of B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (11, 35, 51). Both lan gene clusters are flanked by opuBD- and yvaQ-like sequences (Fig. 3), suggesting that they occupy the same position in the B. subtilis chromosome. In the case of horizontal DNA transfer, the lan cluster would recombine in a distinct chromosomal position. However, given the overall similarity and identity of eri and spa, it is possible that the ericin gene cluster evolved from the subtilin cluster or vice versa. Additionally, the gene order, as well as the overlap of open reading frames of the eri and the spa gene region, is conserved (Fig. 3). Similar to the spa gene cluster, no gene encoding a processing protease (LanP) was detected (32, 51).

Most surprisingly, within the ericin gene cluster, two open reading frames encoding lantibiotic prepropeptides were detected, which were consequently attributed to the initially found eriB-dependent peptides ericin S and ericin A (Fig. 4). Based on sequence similarities, the eriA-eriS gene paralogues are supposed to originate from gene duplication events in which a 354-nt sequence of the eriC gene became inserted between the eriA and eriS gene copies. This eriC sequence portion forms an open reading frame, orf1, of yet unknown function. Due to only four conservative amino acid exchanges, ericin S can be defined as a natural variant of subtilin (2, 22). In contrast, ericin A has 13 amino acid exchanges and a truncation of three amino acid residues at the C terminus (Fig. 4). Conserved positions of serine, threonine. and cysteine residues within the primary structure of ericin S (Fig. 4) in combination with results from Edman degradation and carboxyaminopeptidase MALDI-TOF MS experiments supposed a lanthionine-bridging pattern similar to subtilin (2). The minor amino acid changes of ericin S from subtilin in positions 6 (Val/Leu), 15 (Val/Ala), 24 (Ile/Leu), and 29 (His/Lys) might explain differences between ericin S and subtilin in heat resistance as being due to the slightly changed stability of ring structures, especially in the vicinity of the thioether bridges in positions 6, 24, and 29, as well as explain the few pronounced differences of strain-specific antibiotic properties (Table 4; Fig. 6). The reduced sensitivity of ericin S to trypsin in comparison with subtilin is most probably based upon the exchange of Lys to a His residue in position 29, while the change of Val to Ala in position 15 introduces an additional cleavage site preferred by subtilisin, which might explain the enhanced sensitivity of ericin S. However, pepsin sensitivity was nearly equal due to the same amount of aromatic residues in both molecules. Predictions with respect to the structure and properties of ericin A are more speculative. The abstraction of six water molecules, which is indicated from a molecular mass for the [M + H]+ species (2,986.3 Da) that is 108 Da lower than the calculated mass for the propeptide sequence of ericin A (3,094.5 Da) implies that all Ser/Thr residues of ericin A are in the didehydroamino acid or methyllanthionine stage. Moreover, similar to the case for subtilin and ericin S, no free Cys residues were detectable in ericin A (data not shown), implying that all Cys residues reacted with didehydroamino acids. Since the last two cysteine residues of ericin A (Cys22 and Cys29) are found at different positions from those of subtilin and ericin S (Cys26 and Cys28), the lanthionine-bridging pattern in ericin A should differ from that of subtilin and ericin S. These predictions led us to propose the structure of ericin A as given in Fig. 4, where Cys22 is linked to Thr18 and Cys29 to Thr25. Other intramolecular linkages are less likely because of the size and direction of the bridges. Most strikingly, the leader peptides of ericin A, ericin S, and subtilin have identical amino acid sequences, while for example about half of the residues within the ericin A propeptide part are changed (Fig. 4). This perfect conservation of the leader peptide sequence stresses its highly specific role in lantibiotic biosynthesis (30, 44, 55). Moreover, in contrast to the lacticins LtnA1 and LtnA2 of L. lactis subsp. lactis DPC3147, the “EriBTC” modification machinery apparently tolerates two substrates with such different structures, while the lacticins require separate modification enzymes (40). Consequently, the specificity of biochemical reactions needed for maturation of the two ericins might be similar due to coevolution with the changed substrates (30), while the lacticins require different enzymatic functions.

Surprisingly, ericins A and S exhibited similar physical properties, so that their separation raised a serious problem. Neither by cation-exchange chromatography (not shown) nor by reversed-phase HPLC were ericins S and A separable in two chromatographic steps. Only after a third reversed-phase HPLC step was an ericin A fraction obtained without contamination by ericin S as revealed by MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 5A). For ericin A only slight antibiotic activities were observed, which were similar to the activity of a 100-fold-diluted sample of ericin S. The latter most likely results from contamination of ericin A fractions by ericin S in traces rather than from low specific activity of ericin A. However, the presence and quite different structure of ericin A raise further questions about its physiological role. A synergistic action of both ericins, similar to that of staphylococcin C55 (42), however, is unlikely, as that action was not realized with any test organism (data not shown). Within gene clusters for Pep5, epicidin 280, or lactocin, additional small peptides like PepI, EciI, or Orf57 were found. However, they apparently function in self-protection of the producers and contain no lanthionine residues (30). In fact, the duplication of the ericin genes might have its closest relationship to the lantibiotic streptococcin-producing M-type 49 group Streptococcus strains (29). Here, the two scnA gene copies share 89% identical nucleotides and the ScnA peptides differ only by 4 out of 51 amino acids. One might speculate that the duplication of those genes has led to the creation of a “second peptide” which gained new, i.e., regulatory functions like subtilin or nisin in the two-component regulatory system of SpaR and -K (36) or NisR and -K (34, 37). Indeed, present transcription as well as promoter studies indicated a distinct mode of regulation circuit in the ericin system (B. Hofemeister, J. Feesche, A. Lehr, L. M. Aung-Hilbrich, W. Hillen, and J. Hofemeister, unpublished data).

Acknowledgments

Strain B. subtilis A1/3 was isolated and provided by Erika Griesbach and the Bundesanstalt für Züchtungsforschung an Kulturpflanzen, Aschersleben, Germany. From IPK, Gatersleben, Germany, we thank C. Horstmann for protein sequencing and S. König for DNA sequencing, as well as S. Gorgulla and B. Fischer for expert technical assistance. For the opportunity to use MALDI-TOF MS equipment, we thank M. Karas, University of Frankfurt.

In Gatersleben the studies were supported by grant BEO22/0311137 from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Bonn, Germany).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1995. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Banerjee, S., and J. N. Hansen. 1988. Structure and expression of a gene encoding the precursor of subtilin, a small protein antibiotic. J. Biol. Chem. 263:9508-9514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, W. M. 1994. PCR amplification of up to 35-kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from lambda bacteriophage templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2216-2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borchert, S., S. S. Patil, and M. A. Marahiel. 1992. Identification of putative multifunctional peptide synthetase genes using highly conserved oligonucleotide sequences derived from known synthetases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 92:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breukink, E., and B. de Kruijff. 1999. The lantibiotic nisin, a special case or not? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchman, G. W., S. Banerjee, and J. N. Hansen. 1988. Structure, expression, and evolution of a gene encoding the precursor of nisin, a small protein antibiotic. J. Biol. Chem. 263:16260-16266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, W. C., B. W. Bycroft, M. L. Leyland, L.-Y. Lian, and G. C. K. Roberts. 1993. A novel posttranslational modification of the peptide antibiotic subtilin: isolation and characterization of a natural variant from Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. Biochem. J. 291:23-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, S., and S. N. Cohen. 1979. High frequency transformation of Bacillus subtilis protoplasts by plasmid DNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 168:111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, S., S.-Y. Chang, P. Gravitt, and R. Respess. 1994. Long PCR. Nature 369:684-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopin, A., M. C. Chopin, A. Moillo-Batt, and P. Langella. 1984. Two plasmid determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid 11:260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung, Y. J., and J. N. Hansen. 1992. Determination of the sequence of spaE and identification of a promoter in the subtilin (spa) operon in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:6699-6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrad, B., V. Bashkirov, and J. Hofemeister. 1992. Imprecise excision of plasmid pE194 from the chromosomes of Bacillus subtilis pE194 insertion strains. J. Bacteriol. 174:6997-7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutting, S. M., and P. B. V. Horn. 1990. Genetic analysis, p. 27-74. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.), Molecular biology methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 14.Delves-Broughton, J. 1990. Nisin and its application as a food preservative. J. Soc. Dairy Technol. 43:73-76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vos, W. M., J. W. M. Mulders, R. J. Siezen, J. Hugenholtz, and O. P. Kuipers. 1993. Properties of nisin Z and distribution of its gene, nisZ, in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Entian, K.-D., and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Genetics of subtilin and nisin biosyntheses: biosynthesis of lantibiotics. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 69:109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilmore, M. S., R. A. Segarra, M. C. Booth, C. P. Bogie, L. R. Hall, and D. B. Clewell. 1994. Genetic structure of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1-encoded cytolytic toxin system and its relationship to lantibiotic determinants. J. Bacteriol. 176:7335-7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gish, W., and D. J. States. 1993. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat. Genet. 3:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Götz, F., and B. Schumacher. 1987. Improvements of protoplast transformation in Staphylococcus carnosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 40:285-288. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griesbach, E., and E. Lattauschke. 1991. bertragung von Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis in Tomaten-Hydroponikkulturen und Möglichkeiten zur Bekämpfung des Erregers. Nachrbl. Dtsch. Pflanzenschutzd. (Stuttgart) 43:69-73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross, E., and J. L. Morell. 1971. The structure of nisin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93:4634-4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross, E., H. H. Kiltz, and E. Nebelin. 1973. Subtilin VI: Die Struktur des Subtilins. Hoppe-Seyler's Z. Physiol. Chem. 354:810-812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gryczan, T. J., S. Contente, and D. Dubnau. 1978. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus plasmids introduced by transformation into Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 134:318-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutowski-Eckel, Z., C. Klein, K. Siegers, K. Bohm, M. Hammelmann, and K.-D. Entian. 1994. Growth phase-dependent regulation and membrane localization of SpaB, a protein involved in biosynthesis of the lantibiotic subtilin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofemeister, B., S. König, V. Hoang, J. Engel, G. Mayer, G. Hansen, and J. Hofemeister. 1994. The gene amyE(TV1) codes for a nonglucogenic α-amylase from Thermoactinomyces vulgaris 94-2A in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3381-3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horionuchi, S., and B. Weisblum. 1982. Nucleotide sequence and functional map of pE194, a plasmid that specifies inducible resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin type B antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 150:804-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huber, J., E. Griesbach, R. Pippig, H. Kegler, and S. Richter. November 1991. Mikroorganismus und dessen Verwendung als mikrobielles Pflanzenstärkungsmittel. Deutsches Patentamt DD 295 526.

- 29.Hynes, W. L., V. L. Fried, and J. J. Ferretti. 1994. Duplication of the lantibiotic structural gene in M-type 49 group Streptococcus strains producing streptococcin A-M49. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4207-4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jack, R. W., G. Bierbaum, and H.-G. Sahl. 1998. Lantibiotics and related peptides. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 31.Kaletta, C., and K.-D. Entian. 1989. Nisin, a peptide antibiotic: cloning and sequencing of the nisA gene and posttranslational processing of its peptide product. J. Bacteriol. 171:1597-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiesau, P., U. Eikmanns, Z. Gutowski-Eckel, S. Weber, M. Hammelmann, and K.-D. Entian. 1997. Evidence for a multimeric subtilin synthetase complex. J. Bacteriol. 179:1475-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klaenhammer, T. R. 1993. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:39-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleerebezem, M., L. E. Quadri, O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1997. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal-transduction systems in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 24:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein, C., C. Kaletta, N. Schnell, and K.-D. Entian. 1992. Analysis of genes involved in biosynthesis of the lantibiotic subtilin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:132-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein, C., C. Kaletta, and K.-D. Entian. 1993. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic subtilin is regulated by a histidine kinase/response regulator system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:296-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuipers, O. P., M. M. Beerthuyzen, P. G. de Ruyter, E. J. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27299-27304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leenders, F., T. H. Stein, B. Kablitz, P. Franke, and J. Vater. 1999. Rapid typing of Bacillus subtilis strains by their secondary metabolites using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of intact cells. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 13:943-949. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAuliffe, O., C. Hill, and R. P. Ross. 2000. Each peptide of the two-component lantibiotic lacticin 3147 requires a separate modification enzyme for activity. Microbiology 146:2147-2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulders, J. W., I. J. Boerrigter, H. S. Rollema, R. J. Siezen, and W. M. de Vos. 1991. Identification and characterization of the lantibiotic nisin Z, a natural nisin variant. Eur. J. Biochem. 201:581-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Navaratna, M. A., H.-G. Sahl, and J. R. Tagg. 1998. Two-component anti-Staphylococcus aureus lantibiotic activity produced by Staphylococcus aureus C55. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4803-4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paik, S. H., A. Chakicherla, and J. N. Hansen. 1998. Identification and characterization of the structural and transporter genes for, and the chemical and biological properties of sublancin 168, a novel lantibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23134-23142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul, L. K., G. Izaguirre, and J. N. Hansen. 1999. Studies of the subtilin leader peptide as a translocation signal in Escherichia coli K12. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose, M., and K.-D. Entian. 1996. New genes in the 170 degrees region of the Bacillus subtilis genome encode DNA gyrase subunits, a thioredoxin, a xylanase and an amino acid transporter. Microbiology 142:3097-3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rince, A., A. Dufour, S. Le Pogam, D. Thuault, C. M. Bourgeois, and J. P. Le Pennec. 1994. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of genes involved in production of lactococcin DR, a bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1652-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sahl, H. G., and G. Bierbaum. 1998. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:41-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook, J., E. J. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 49.Schnell, N., K.-D. Entian, U. Schneider, F. Götz, H. Zahner, R. Kellner, and G. Jung. 1988. Prepeptide sequence of epidermin, a ribosomally synthesized antibiotic with four sulphide-rings. Nature 333:276-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siegers, K., S. Heinzmann, and K.-D. Entian. 1996. Biosynthesis of lantibiotic nisin. Posttranslational modification of its prepeptide occurs at a multimeric membrane-associated lanthionine synthetase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271:12294-12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siezen, R. J., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Comparison of lantibiotic gene clusters and encoded proteins. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 69:171-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steller, S., D. Vollenbroich, F. Leenders, T. Stein, B. Conrad, J. Hofemeister, P. Jaques, S. P. Thonard, and J. Vater. 1999. Structural and functional organization of the fengycin synthetase multienzyme system from Bacillus subtilis b213 and A1/3. Chem. Biol. 6:31-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tichaczek, P. S., R. Vogel, and W. P. Hammes. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of sakP encoding sakacin P, the bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus sake LTH 673. Microbiology 140:361-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanittanakom, N., W. Loeffler, U. Koch, and G. Jung. 1986. Fengycin—a novel antifungal lipopeptide antibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis F-29-3. J. Antibiot. 39:888-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Kraaij, C., W. M. de Vos, R. J. Siezen, and O. P. Kuipers. 1999. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis, mode of action and applications. Nat. Prod. Rep. 16:575-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vary, P. S., and Y.-P. Tao. 1988. Development of genetic methods in Bacillus megaterium, p. 403-407. In A. T. Ganesan and J. A. Hoch, (ed.), Genetics and biotechnology of bacilli, vol. 2. Academic Press, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]