Abstract

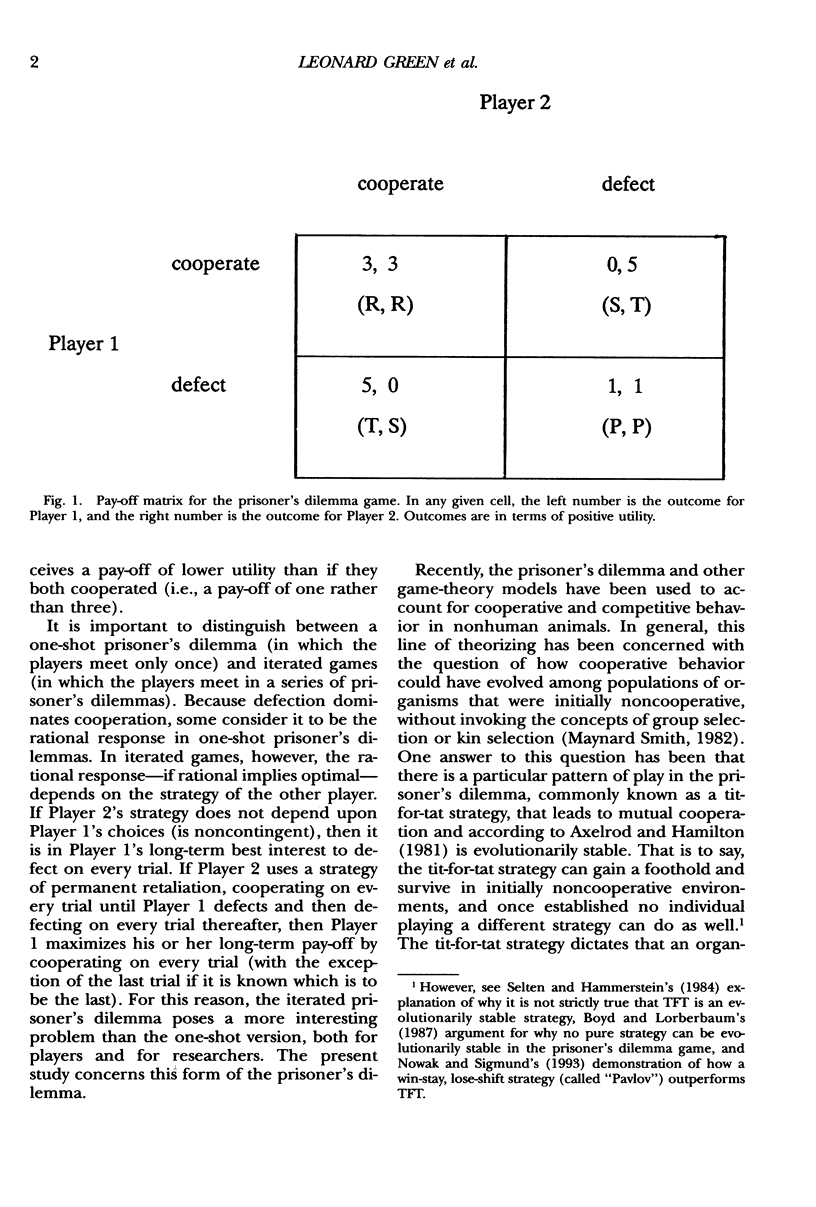

In three experiments pigeons played (i.e., chose between two colored keys) iterated prisoner's dilemma and other 2 × 2 games (2 participants and 2 options) against response strategies programmed on a computer. Under the prisoner's dilemma pay-off matrix, the birds generally defected (i.e., pecked the color associated with not cooperating) against both a random response (.5 probability of either alternative) and a tit-for-tat strategy (on trial n the computer “chooses” the alternative that is the same as the one chosen by the subject on trial n – 1) played by the computer. They consistently defected in the tit-for-tat condition despite the fact that as a consequence they earned about one third of the food that they could have if they had cooperated (i.e., pecked the “cooperate” color) on all the trials. Manipulation of the values of the food pay-offs demonstrated that the defection and consequent loss of food under the tit-for-tat condition were not due to a lack of sensitivity to differences in pay-off values, nor to strict avoidance of a null pay-off (no food on a trial), nor to insensitivity to the local (current trial) reward contingencies. Rather, the birds markedly discounted future outcomes and thus made their response choices based on immediate outcomes available on the present trial rather than on long-term delayed outcomes over many trials. That is, the birds were impulsive, choosing smaller but more immediate rewards, and did not demonstrate self-control. Implications for the study of cooperation and competition in both humans and nonhumans are discussed.

Keywords: prisoner's dilemma, 2 × 2 games, tit for tat, self-control, cooperation, key peck, pigeons

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Axelrod R., Hamilton W. D. The evolution of cooperation. Science. 1981 Mar 27;211(4489):1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.7466396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo M. P. Mutual Restraint in Tree Swallows: A Test of the TIT FOR TAT Model of Reciprocity. Science. 1985 Mar 15;227(4692):1363–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4692.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milinski M. TIT FOR TAT in sticklebacks and the evolution of cooperation. 1987 Jan 29-Feb 4Nature. 325(6103):433–435. doi: 10.1038/325433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak M., Sigmund K. A strategy of win-stay, lose-shift that outperforms tit-for-tat in the Prisoner's Dilemma game. Nature. 1993 Jul 1;364(6432):56–58. doi: 10.1038/364056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H., Green L. Commitment, choice and self-control. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 Jan;17(1):15–22. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.17-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H., Raineri A., Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. J Exp Anal Behav. 1991 Mar;55(2):233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B. F. The phylogeny and ontogeny of behavior. Contingencies of reinforcement throw light on contingencies of survival in the evolution of behavior. Science. 1966 Sep 9;153(3741):1205–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3741.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]