Abstract

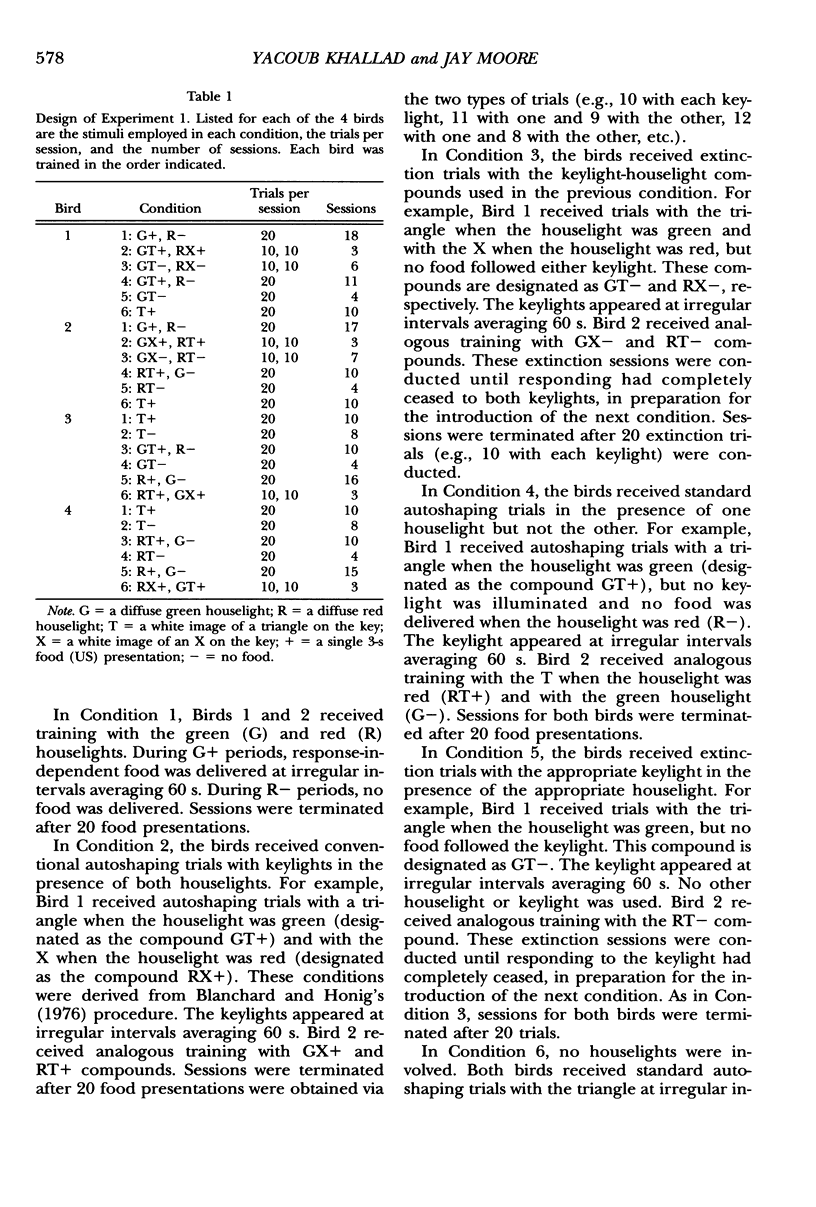

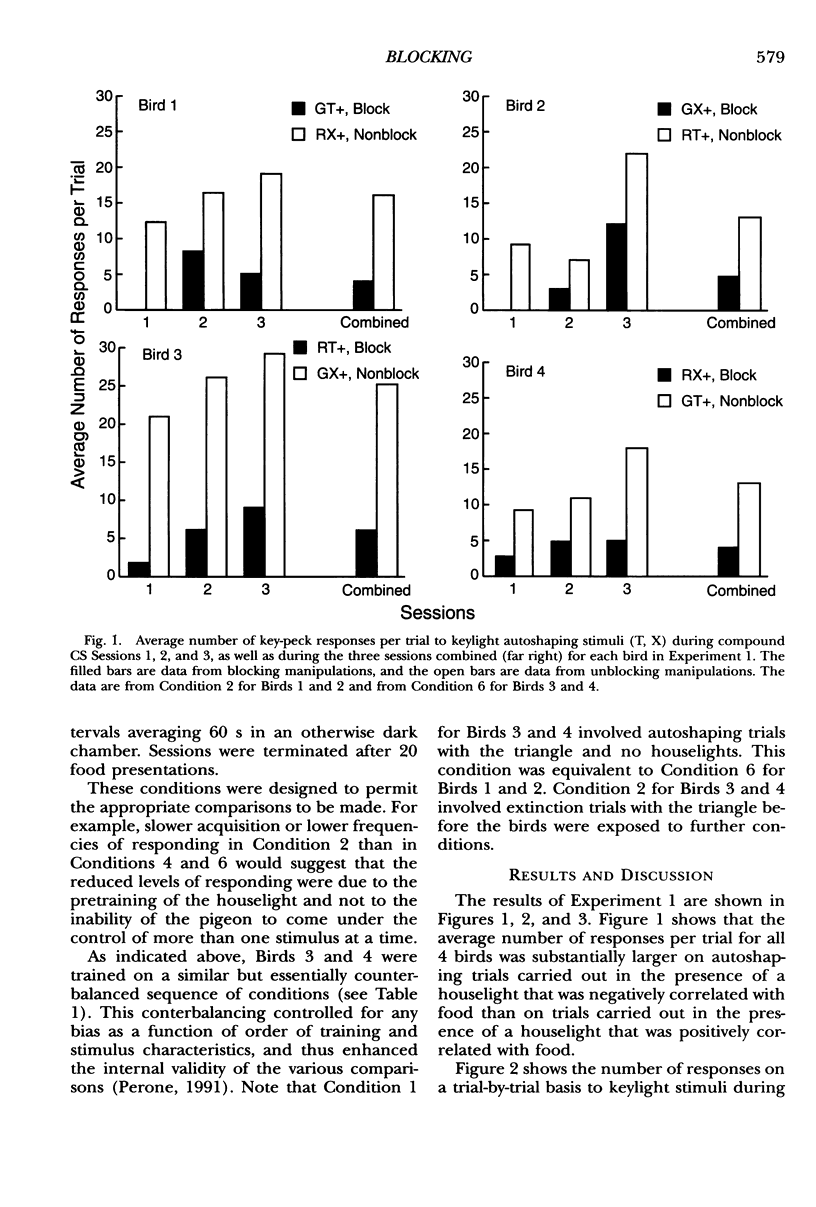

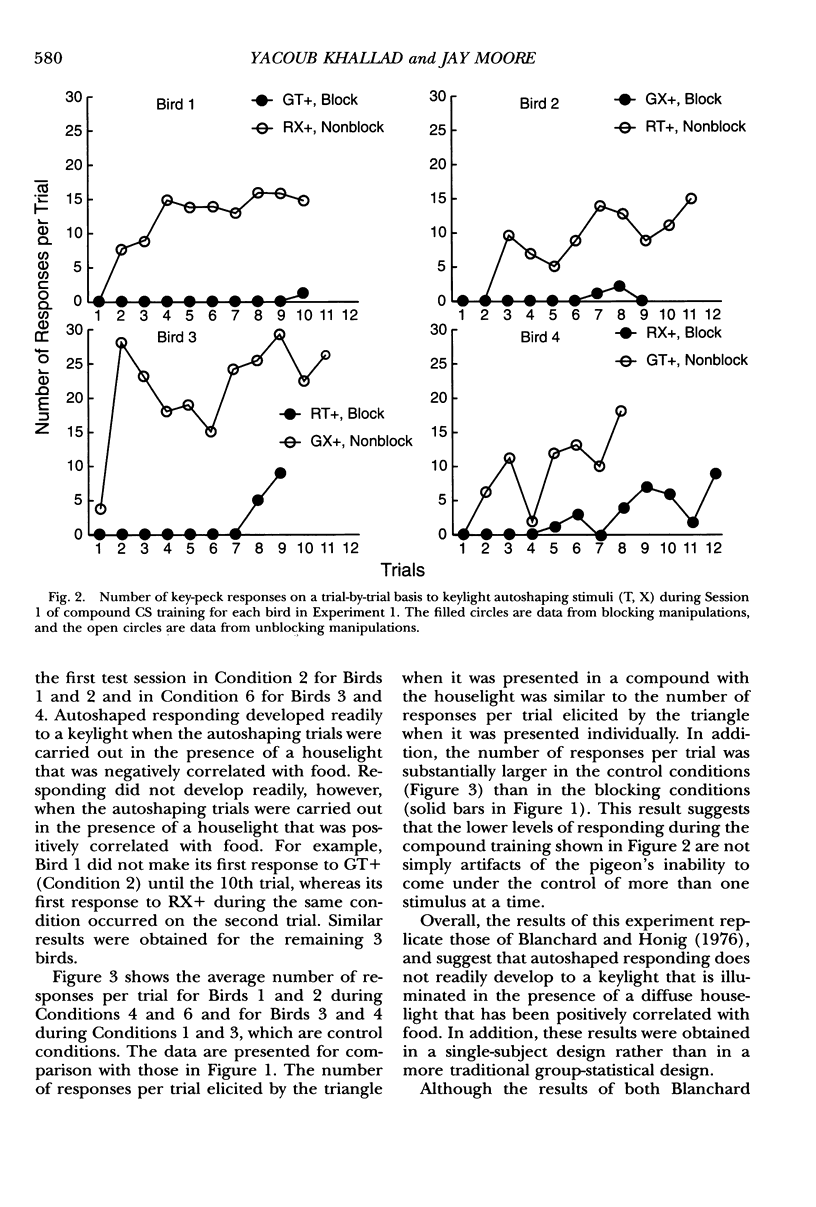

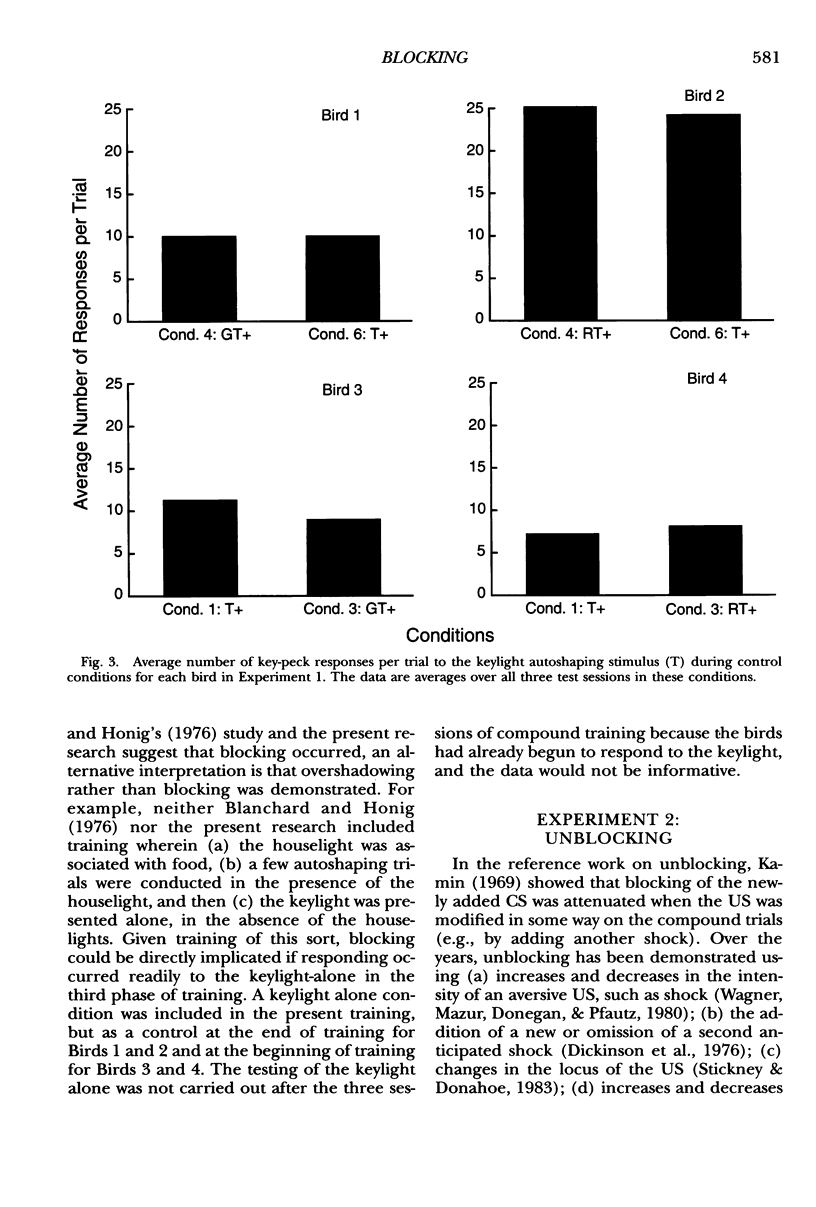

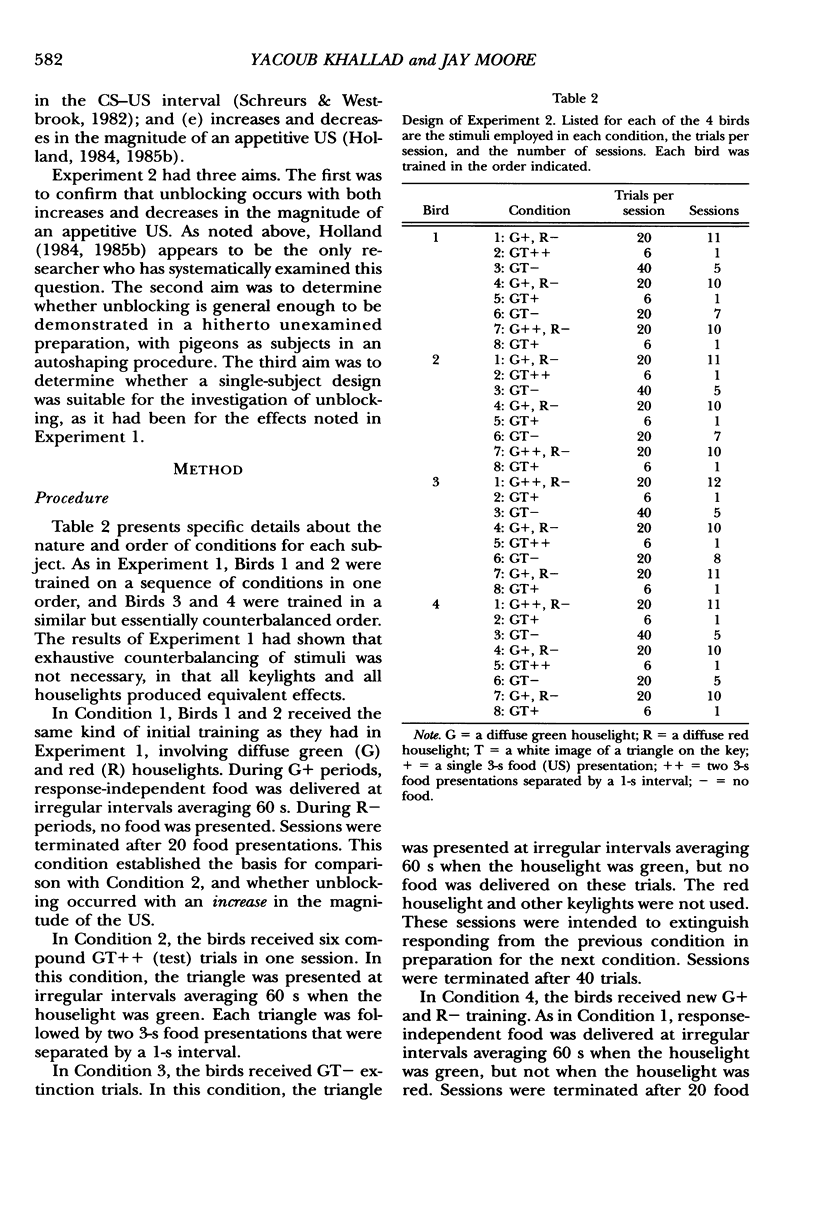

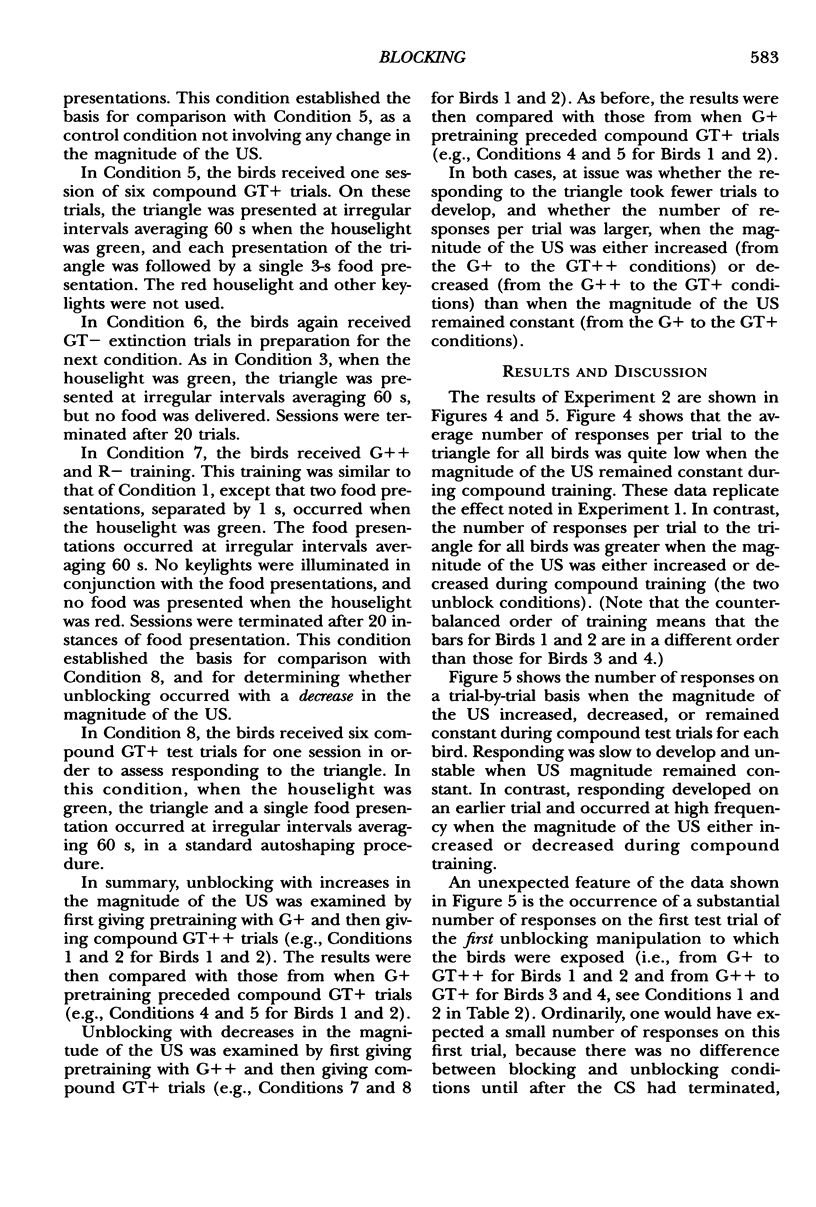

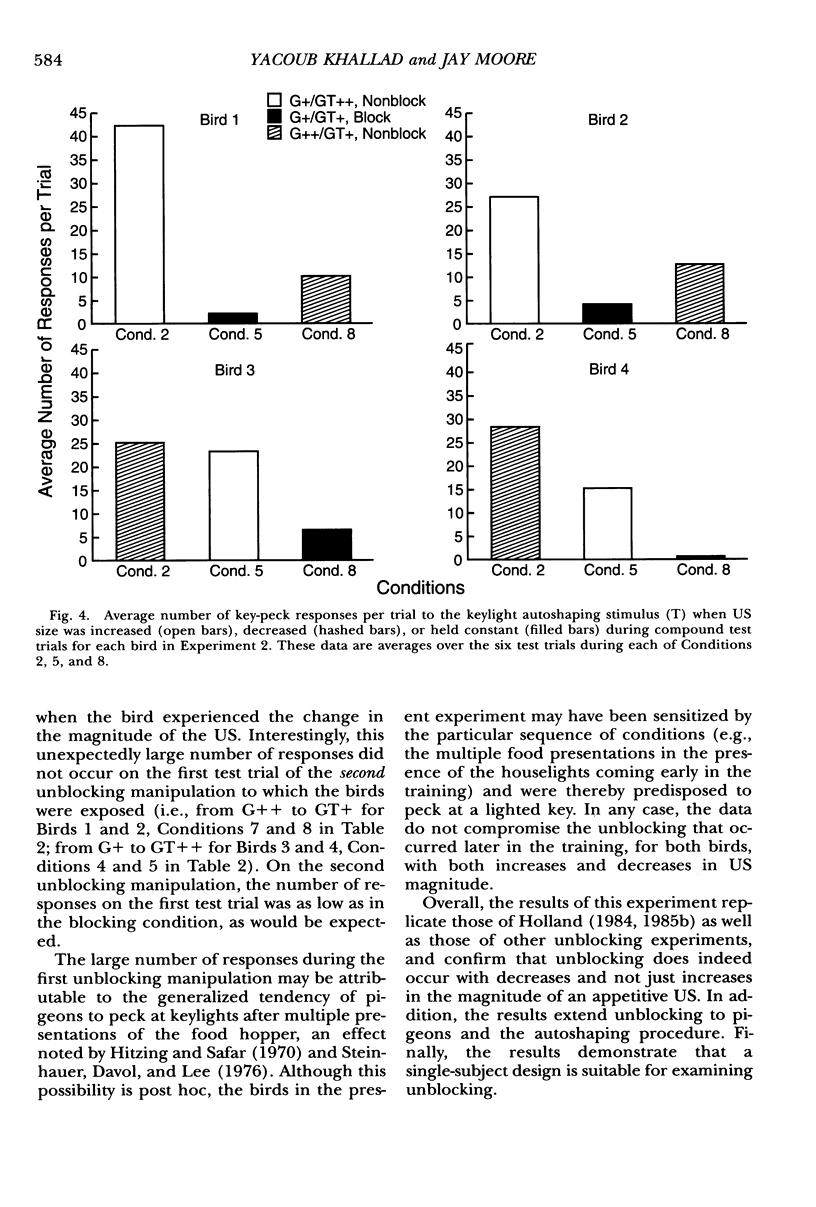

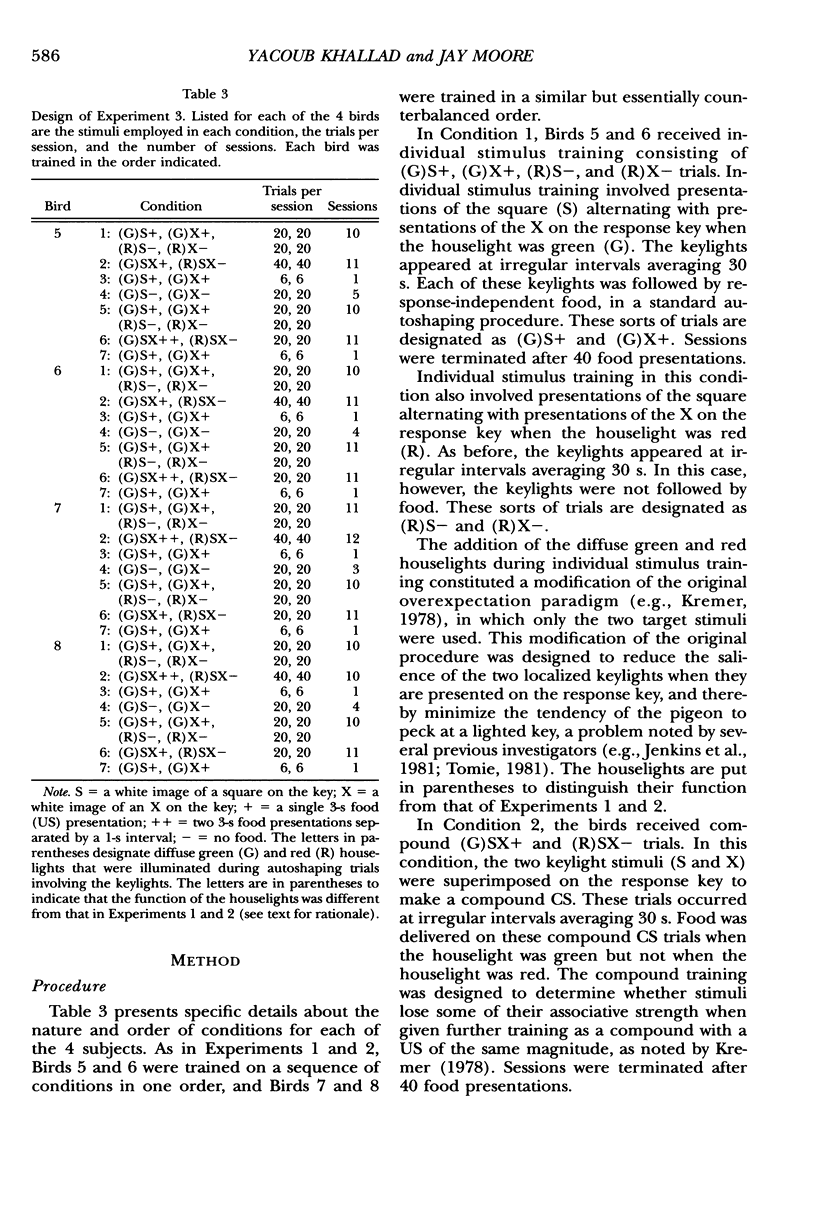

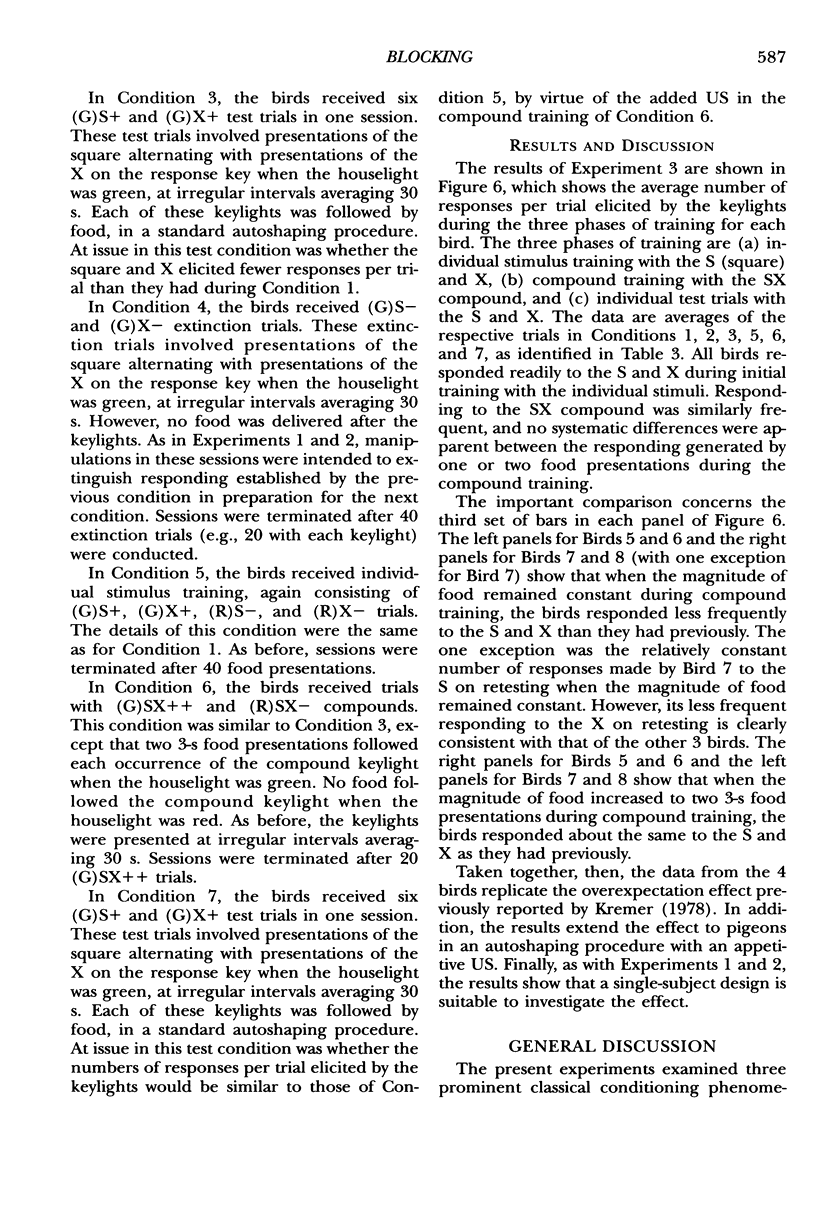

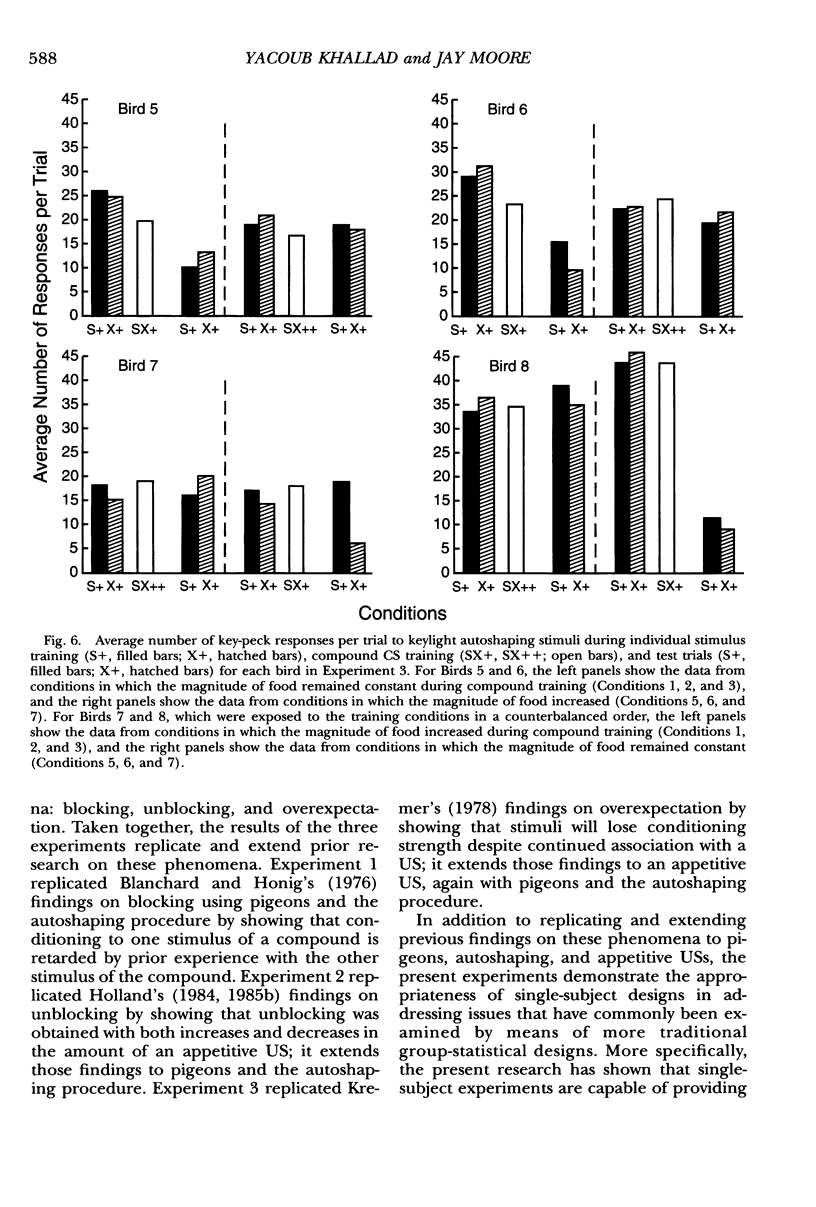

Three experiments used pigeons in an autoshaping procedure and a single-subject design to examine compound stimulus control in classical conditioning. Experiment 1 examined the blocking effect, and Experiment 2 examined the unblocking effect. In both experiments, response-independent food was first delivered intermittently in the presence of one distinctively colored houselight but not another. Then, conventional autoshaping trials were carried out in the presence of each houselight. In Experiment 1, the keylight readily elicited responding in the presence of the houselight that had been negatively correlated with food, but not in the presence of the houselight that had been positively correlated with food. In Experiment 2, the keylight readily elicited responding in the presence of the houselight positively correlated with food, but only when the amount of food used on the autoshaping trials was either greater or less than that previously delivered in the presence of the houselight. Experiment 3 examined the overexpectation effect. Conventional autoshaping trials were first carried out by presenting each of two keylights individually. Then, additional autoshaping trials were carried out by presenting the two keylights as a compound, with either the same amount of food or a greater amount of food per trial. Finally, the keylights were retested by again presenting them individually. The number of responses per trial elicited by the keylights decreased when the amount of food used in compound trials was the same as that used in individual trials. However, the number of responses per trial remained approximately the same when the amount of food used in compound trials was greater than that used in individual trials. Taken together, the results of the three experiments demonstrate (a) the generality of the blocking, unblocking, and overexpectation effects by virtue of their extension to appetitive unconditioned stimuli; (b) the suitability of pigeons as subjects and autoshaping as a procedure for studying classical conditioning; and (c) the appropriateness of single-subject designs.

Keywords: blocking, unblocking, overexpectation, Rescorla–Wagner model, autoshaping, key peck, pigeons

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Kremer E. F. The Rescorla-Wagner model: losses in associative strength in compound conditioned stimuli. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1978 Jan;4(1):22–36. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.4.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce J. M., Hall G. A model for Pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychol Rev. 1980 Nov;87(6):532–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs B. G., Westbrook R. F. The effects of changes in the CS-US interval during compound conditioning upon an otherwise blocked element. Q J Exp Psychol B. 1982 Feb;34(Pt 1):19–30. doi: 10.1080/14640748208400887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer G. D., Davol G. H., Lee A. Acquisition of the autoshaped key peck as a function of amount of preliminary magazine training. J Exp Anal Behav. 1976 May;25(3):355–359. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1976.25-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. R., Mazur J. E., Donegan N. H., Pfautz P. L. Evaluation of blocking and conditioned inhibition to a CS signaling a decrease in US intensity. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1980 Oct;6(4):376–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]