Abstract

The Bacillus subtilis PyrR protein regulates transcriptional attenuation of the pyrimidine nucleotide (pyr) operon by binding in a uridine nucleotide-dependent manner to specific sites on pyr mRNA and stabilizing a secondary structure of the downstream RNA that favors termination of transcription. The high-resolution structure of unliganded PyrR was used to guide site-directed mutagenesis of 12 amino acid residues that were thought likely to be involved in the binding of RNA. Missense mutations were constructed and evaluated for their effects on regulation of pyr genes in vivo and their uracil phosphoribosyltransferase activity, which is catalyzed by wild-type PyrR. A substantial fraction of the mutant PyrR proteins did not have native structures, but eight PyrR mutants were purified and characterized physically, for their uracil phosphoribosyltransferase activity and for their ability to bind pyr RNA in vitro. On the basis of these studies Thr-18, His-22, Arg-141, and Arg-146 were implicated in RNA binding. Arg-27 and Lys-152 were also likely to be involved in RNA binding, but Gln substitution mutations in these residues may have altered their subunit-subunit interactions slightly. Arg-19 was implicated in pyr regulation, but a specific role in RNA binding could not be demonstrated because the R19Q mutant protein could not be purified in native form. The results confirm a role in RNA binding of a positively charged face of PyrR previously identified from the crystallographic structure. The RNA binding residues lie in two sequence segments that are conserved in PyrR proteins from many species.

Repression of the genes of de novo pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis (pyr genes) by exogenous pyrimidines is mediated in many bacteria by the PyrR regulatory protein. This protein, which has been most extensively characterized in studies with Bacillus subtilis, acts by binding specifically to a defined sequence in transcriptional attenuation regions that lie upstream of the structural genes in pyr mRNA. Binding of PyrR to pyr mRNA disrupts an antiterminator hairpin in the RNA and favors formation of a downstream transcription terminator. Since binding of the PyrR protein to RNA is much tighter in the presence of UMP or UTP (2), elevated levels of these nucleotides act to increase termination of transcription with consequent reduction in expression of the downstream pyr genes. A detailed review of studies of B. subtilis PyrR and its role in the regulation of the B. subtilis pyr operon was published in 1999 (15).

A description of the RNA sequence and secondary structural requirements for binding by B. subtilis PyrR has been obtained from a combination of phylogenetic comparisons (2, 15), characterization of mutations in the RNA that cause loss of regulation in vivo (5), PyrR footprinting studies (2), and studies of the binding of a large collection of RNA structural variants to PyrR in vitro (2). In contrast, relatively little is known about the amino acid residues in PyrR that are involved in specific interactions with pyr mRNA. An approach to addressing this question by in vitro mutagenesis of the PyrR protein was provided by the determination of the three-dimensional structure of PyrR at high resolution (16). That structure revealed a single face of the PyrR dimer that was rich in positively charged and neutral amino acid residues, whereas the rest of the surface of the protein had predominantly negatively charged surface residues. In the present work, PyrR mutations that replaced residues in its putative RNA-binding surface with amino acid residues that should reduce or abolish their ability to bind to RNA were constructed and characterized. Gln replaced Arg and Lys residues, and other residues were replaced by Ala. In addition, a number of mutations in PyrR were isolated by Ghim and Switzer (6) in a screen for pyrR mutants that abolished normal repression of pyr genes by exogenous uracil and uridine in vivo. Some of these mutants were identified as missense mutants, but the mutant proteins were not isolated and characterized. Two of these mutants were further characterized in this study. The results of this study confirm the previous tentative assignment of an mRNA binding site on PyrR. Six amino acid residues in PyrR that are important for normal binding of pyr mRNA and for normal regulation of pyr genes in vivo were identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the pyrR gene was carried out by a one-step PCR method adapted from a published procedure (19). The following changes were made to the protocol. Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.) was used in place of Taq polymerase. ThermoPol buffer, which is supplied with the Vent polymerase, was used instead of the mutagenesis buffer. A hot-start cycle consisting of 3 min at 94°C followed by 10 min at the annealing temperature was used for each PCR. Thirty cycles of PCR were carried out instead of the recommended 5 to 10 cycles. The cycles were as follows: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at the annealing temperature, and 1 min at 72°C. The annealing temperature was specific for each set of primers. The PCR products were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase after the DpnI digestion (19). The PyrR overexpression plasmid pTSROX3 (17) was used as the template.

In vivo expression.

The pyrR gene was integrated into the B. subtilis chromosome by using the pDH32 plasmid (7). The pyrR genes from the mutagenized pTSROX3 vectors were removed from the overexpression vector by digestion with EcoRI and NarI and were ligated into pDH32 that had been digested with EcoRI and ClaI. The pDH32 plasmids containing the pyrR genes were transformed into competent B. subtilis DB104ΔpyrR (18) or DB104ΔpyrR upp::erm cells. DB104ΔpyrR upp::erm was constructed by transformation of strain DB104ΔpyrR upp::cm (J. D'Elia, unpublished data) with pCm::Em (14) which had been digested with EcoRI. Since pDH32 can replicate in Escherichia coli, but not in B. subtilis, selection with chloramphenicol forced the plasmid bearing the mutant pyrR genes to integrate into the amyE locus of the B. subtilis chromosome (18). To check for proper integration, the cells were screened for amyE disruption by using a starch-iodine test (8).

ATCase assay.

Cultures (50 ml) of B. subtilis DB104ΔpyrR carrying the wild-type or mutant pyrR genes integrated at amyE were grown on buffered minimal medium (10) containing 100 μg of histidine/ml to late log phase. Cells were grown both in the presence and in the absence of exogenous uracil and uridine (50 μg/ml each). The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min), resuspended in 5 ml of buffer R (17), and ruptured by sonication. The extracts were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used for aspartate transcarbamylase (ATCase) assays as previously described (1, 13).

ELISAs.

To determine the amount of PyrR protein in B. subtilis crude extracts, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed using polyclonal antibodies to PyrR that were raised in rabbits at the Immunological Resource Center at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. The crude extracts were applied to a 96-well plate by serial dilution to obtain a range of protein concentrations from 150 to 3 ng/well. The plates were then wrapped in plastic wrap and incubated at room temperature overnight. The plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2 to 7.5) containing 0.5% polyoxyethylenesorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20). After washing, the wells were filled with blocking solution (2% nonfat dry milk in PBS), and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The plates were then washed three times with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20. Fifty microliters of a 1/2,000 dilution of primary antibody (rabbit anti-PyrR immunoglobulin G) was added to each well. The primary antibody was incubated at room temperature for 30 min before the plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20. Then 50 μl of a 1/20,000 dilution of secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase [Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.]) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The plates were again washed three times with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20. The ELISA was developed by adding 100 μl of substrate (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine plus H2O2 from Pierce Chemical Co.). After a 30-min incubation at room temperature the reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl of 4 N H2SO4. Colorimetric data from the titer plates were collected on an Elx800 Universal Microplate Reader from Bio-Tek Instruments Inc. (Winooski, Vt.). Standard curves were determined using purified PyrR protein in a range from 200 to 4.7 pg/well and using crude extracts from DB104ΔpyrR upp::erm to which the same amounts of purified PyrR protein were added.

Overexpression and purification of mutant PyrR proteins.

Overexpression and purification of the mutant PyrR proteins were carried out as described by Turner et al. (17) with the following adaptations. The initial precipitation with 35% saturated ammonium sulfate was omitted. PyrR was eluted from the Q-Sepharose FF column with an 800-ml linear gradient from 150 to 250 mM NaCl in buffer R, so that the dialysis prior to the column was against buffer R with 150 mM NaCl, and the column was equilibrated with this buffer. Pooled column fractions were concentrated as described elsewhere (2), and the protein was precipitated with 75% saturated ammonium sulfate, omitting precipitation with 50% saturated ammonium sulfate. The final dialysis buffer was 100 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.5)-10 mM potassium acetate-20% glycerol.

To purify mutant PyrR protein R19Q from inclusion bodies, a 3-liter culture of E. coli SØ408 bearing a plasmid that overexpressed the R19Q PyrR protein was grown for 15 h on Luria broth (12) containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 15 min) and washed with 0.9% NaCl. The cells were resuspended and sonicated according to the protocol for normal PyrR purification (17). After sonication the inclusion bodies were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 ml of 100 mM buffer R containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and 12 ml of 8 M guanidine hydrochloride was added. The denatured protein sample (22 ml) was dialyzed against buffer R overnight with four changes of buffer. The sample was then centrifuged, and the supernatant containing soluble R19Q PyrR protein was loaded onto the Q-Sepharose FF column. The R19Q PyrR protein was eluted from the column with a gradient from 300 mM to 1 M NaCl in buffer R. The pooled fractions containing R19Q PyrR were concentrated to 15 ml and dialyzed into 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.5) for storage.

UPRTase assay.

Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRTase) assays of purified PyrR proteins and B. subtilis crude extracts were carried out at 37°C. Each reaction mixture consisted of 20 μl of assay mix, 20 μl of protein dilution, and 10 μl of uracil mix (a mixture of [14C]uracil and unlabeled uracil). The final reaction mixture contained 90 mM serine (pH 8.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate, and 0.2 mM uracil. The final reaction mixture pH at 37°C was 8.6. Samples (5 μl) from each reaction mixture were taken at various times, and the amount of [14C]UMP formed was determined by spotting samples on DEAE cellulose paper, followed by washing and scintillation counting as described by Turner et al. (17).

Electrophoretic gel mobility shift analysis of RNA binding to PyrR.

Electrophoretic gel mobility shift assays of the mutant PyrR proteins were performed as previously described (17) with the following changes. Binding constants were determined by fitting the data to a regular hyperbolic binding curve using the Solver function in Microsoft Excel 97. Each reaction mixture consisted of 10 μl of binding mix, 5 μl of protein dilution, and 5 μl of binding loop 2 (BL2) RNA to give a concentration of 50 pM RNA in the reaction mixture (1 pM RNA was used in some of the UTP binding studies). 32P-labeled BL2 RNA was transcribed and purified according to a published protocol (17). The final concentration of each reagent in the binding mix was 25 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.5), 50 mM K-acetate, 1 mM Mg-acetate, 100 μg of heparin/ml, 0.01% Igepal CA-630, 5% glycerol, 0.25 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 2.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 0.08 U of SuperAse-IN (Ambion, Austin, Tex.)/μl.

High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) molecular sieving chromatography.

The molecular weight of all the mutant PyrR proteins was determined with a Beckman Systems Chromatograph, Gold model, with a 125 Solvent Module and a 168 detector. The molecular sieving column used was a Bio-Rad Bio-Sil SEC 250 column with dimensions of 300 by 7.8 mm. The protein was diluted and eluted with 0.1 M Na-phosphate-0.15 M NaCl-0.01 M Na-azide, pH 6.8, and the column was developed at room temperature at a speed of 1 ml/min, with the absorbance being monitored at 280 nm. Each mutant PyrR protein was analyzed at an initial concentration of 1 mg/ml. A standard curve for estimating molecular weights from the elution times from the column was determined with gel filtration standards from Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.).

Circular dichroism.

Far UV circular dichroism spectra were determined using a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter and a 0.1-cm circular quartz cuvette. Tris-acetate (100 mM, pH 7.5)-10 mM potassium acetate-20% glycerol buffer was used to dilute all the samples to 1 mg/ml. A buffer blank was subtracted from each spectrum. The α-helical content of each mutant PyrR protein was determined from the molar ellipticity at 222 nm by the empirical expression of Chen et al. (3).

Differential scanning calorimetry.

Thermal denaturation of wild-type and mutant PyrR proteins was analyzed by differential scanning colorimetry with a Micro Calorimetry Systems unit from Microcal, Inc. (Northampton, Mass.). The data were analyzed with the Origin software supplied with the instrument. Protein samples (1 mg/ml in 100 mM Tris-acetate [pH 7.5], 10 mM potassium acetate, and 20% glycerol) were scanned from 25 to 80°C at a rate of 80°C/h. A sample with buffer only was placed in the reference chamber and subtracted from the sample chamber data. Transition points (melting temperature [Tm] values) for thermal denaturation were reproducible within 2°C. Some protein precipitation occurred during the analyses, and the thermal denaturation observed was not reversible.

RESULTS

Characterization of PyrR mutants expressed from single gene copies in B. subtilis.

Thirteen mutations in the B. subtilis pyrR gene were examined for alterations in the ability of the mutant PyrR protein to regulate the pyr operon. This was assessed from assays of the ATCase, the product of the pyrB gene, in cells grown on either minimal medium or minimal medium to which excess pyrimidines were added (Table 1). The mutant pyrR genes were constructed, introduced into the integration vector pDH32, and then integrated into the chromosome of B. subtilis strain DB104ΔpyrR by crossover at the amyE locus as described in Materials and Methods. Thus, in each of these strains the normal pyrR gene was deleted and replaced by a single copy of the mutant pyrR gene. A copy of the wild-type pyrR gene was similarly integrated into the amyE locus of strain DB104ΔpyrR; this strain served as a control for the strains bearing mutant genes. Regulation of ATCase in this strain was similar to that observed for strain DB104 (18), i.e., in a strain with pyrR in its native genetic locus. Strain DB104ΔpyrR itself, in which all ability of exogenous pyrimidines to repress the pyr operon has been lost (18), was the negative control. To test whether the mutant PyrR proteins were expressed at normal levels and were folded normally, we used an ELISA to determine the concentration of PyrR cross-reactive protein in the soluble fraction of crude extracts, i.e., after centrifugation of the sonicated cells, and we measured the specific activity of the UPRTase activity catalyzed by PyrR. These latter determinations were conducted for strains in which the mutant pyrR genes were integrated into a DB104ΔpyrR upp::erm double mutant that was devoid of UPRTase activity.

TABLE 1.

Properties of mutant PyrR proteins expressed from single gene copies in B. subtilis in vivo

| pyrR gene product expressed | Sp act (nmol/min/mg) of ATCasea

|

PyrR concn (ng/ml) by ELISAb | Sp act (μmol/min/mg) of UPRTaseb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Ura Urd | −Ura Urd | |||

| None | 3,300 | 3,300 | ||

| Wild type | 4 | 60 | 9 | 7 |

| R15Q | 3 | 45 | 2 | 14 |

| T18A | 5 | 750 | 8 | 15 |

| R19Q | 1,600 | 2,600 | 14 | 12 |

| H22A | 1,100 | 2,600 | 5 | 8 |

| R27Q | 3 | 140 | 5 | 0.6 |

| T41I | 34 | 200 | 9 | None |

| H140A | 24 | 450 | 8 | 3 |

| H140A/V164I | 1,300 | 1,900 | 22 | None |

| R141Q | 1,400 | 1,500 | 20 | 9 |

| R146Q | 40 | 860 | 11 | 8 |

| Y149A | 2 | 130 | 0.9 | None |

| K152Q | 9 | 100 | 0.6 | None |

| T156I | 100 | 430 | 0.5 | 10 |

pyrR genes were integrated into strain DB104ΔpyrR.

pyrR genes were integrated into strain DB104ΔpyrR upp::em.

Expression of ATCase in the DB104ΔpyrR host strain was very high and was not repressed by growth of the cells in the presence of excess uracil and uridine (Table 1). Introduction of a wild-type pyrR gene into this strain restored normal regulation. In this case expression of ATCase was much lower than the fully derepressed level even when the cells were grown without exogenous pyrimidines; this reflects substantial repression by endogenous uridine nucleotides under these growth conditions. Four of the pyrR mutants examined were essentially unable to regulate pyr gene expression. These were R19Q, H22A, R141Q, and H140A/V164I (the V164I substitution was discovered to be an unintended additional mutation during sequencing of the intended H140A mutant candidate). Three of these produced PyrR cross-reactive protein at normal levels and had normal UPRTase activity. The fourth mutant, H140A/V164I, produced normal levels of cross-reactive protein but had no detectable UPRTase activity, suggesting that it was not properly folded. Since the desired mutant, H140A, was later isolated, the double mutant was not further studied. These findings identified Arg-19, His-22, and Arg-141 as good candidates for amino acid residues likely to play a crucial role in regulation of pyr genes.

Several other pyrR mutants displayed defects in regulation of ATCase activity that were not as severe as those of the three mutants just described. These mutants fell into two classes. Mutants H140A and R146Q retained some ability to repress ATCase activity but showed significantly reduced repression whether or not the cells were grown with excess pyrimidines. Both mutant proteins were produced at normal levels; R146Q had normal UPRTase specific activity, but the UPRTase activity of H140A appeared to be low. Contingent on further characterization, we assigned Arg-146 and His-140 as possibly playing significant roles in regulation by PyrR. Two pyrR mutants identified by Ghim and Switzer (6), T41I and T156I, also belonged in this category, but interpretation of their effects in vivo was made ambiguous because T41I lacked detectable UPRTase activity and T156I was produced at very low levels.

The other class of pyrR mutants with regulatory defects displayed normal repression when the test strains were grown with excess pyrimidines but had less-than-normal repression when they were grown on minimal medium. Mutants in this class were T18A, R27Q, Y149A, and K152Q. PyrR T18A was produced at normal levels and had normal UPRTase specific activity. Mutants Y149A and K152Q were produced at significantly lower-than-normal levels, which made interpretation of results of their effects in vivo uncertain. Even though cells containing PyrR R27Q were capable of full repression of pyrB when they were grown with excess pyrimidines, the abnormally low UPRTase specific activity of the protein in crude extracts raised doubts whether the protein was folded normally.

In summary, the results of the in vivo studies identified Thr-18, Arg-19, His-22, His-140, Arg-141, and Arg-146 as good candidates for amino acids that might be involved in RNA binding or some other specific aspect of pyr regulation. Arg-15 did not appear to be involved in these functions. As noted above, a number of other mutants may have also had defects in RNA binding, but they were produced at very low levels or had abnormal UPRTase specific activity, which rendered interpretation ambiguous.

Characterization of recombinant PyrR mutant proteins after overexpression in E. coli and purification.

Further characterization of the biochemical nature of the defects in the mutant PyrR proteins described above required isolation of the pure proteins. Since the mutant pyrR genes were constructed in the pTSROX3 plasmid previously used by Turner et al. (17) for the overexpression and purification of wild-type PyrR in E. coli, the same protocol was used for the mutant PyrR proteins. Only 6 of the 13 mutant PyrR proteins described in Table 1 behaved in the same way as did wild-type PyrR when this procedure was followed. These were T18A, H22A, R27Q, R141Q, R146Q, and K152Q. The PyrR proteins produced by three of the mutants under these overexpression conditions, R19Q, Y149A, and T156I, were found in inclusion bodies, which indicated that they did not fold correctly and were insoluble in vivo. Nonetheless, we attempted to renature one of these mutant proteins, R19Q, by dissolving the inclusion bodies in guanidine hydrochloride, followed by dialysis into buffer (see Materials and Methods). Renatured mutant PyrR R19Q was characterized as an example of the proteins that formed inclusion bodies. Three more PyrR mutants, R15Q, H140A, and T41I, were not produced in inclusion bodies in E. coli but did not behave like wild-type PyrR during purification. With each of these three mutants a significant portion of the PyrR protein was found in the precipitated fraction after centrifugation of the crude extract, fractionation of the PyrR protein by ammonium sulfate precipitation was abnormal, and the distribution of the PyrR protein during chromatography on QAE-Sepharose was much broader than that with the wild-type PyrR. The greater-than-normal tendency of these proteins to aggregate was an indication that they are not folded normally. A single example of this group of mutants, T41I, was purified and characterized further.

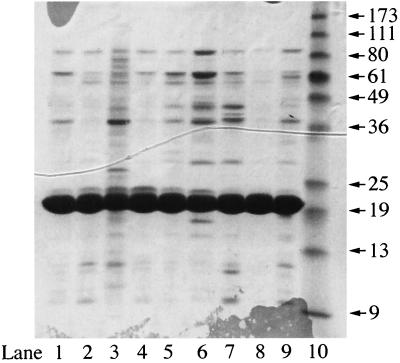

The purity of the eight mutant PyrR proteins was shown by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to be 90% or better (Fig. 1). The two mutant proteins that did not behave normally on purification, R19Q and T41I, contained more contaminating proteins than did the other six mutant proteins. Physical and functional properties of the purified proteins are shown and compared to those of wild-type PyrR in Table 2. Three physical properties were used to assess whether the purified proteins had native folded structures. These were the native molecular weight of the PyrR on molecular sieving chromatography by HPLC, circular dichroic spectra, and thermal stability as assessed by differential scanning calorimetry. Six of the mutants had physical properties quite similar to those of wild-type PyrR by all three criteria. As we expected from their aberrant behavior during purification, the purified R19Q and T41I mutant PyrR proteins were highly aggregated and showed other evidence of abnormal folding. This conclusion was further supported by the observation that these two mutant proteins were the only ones that had significantly lower UPRTase specific activity in vitro than did wild-type PyrR.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of purified preparations of mutant PyrR proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A 10-μg sample of each protein was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 15% polyacrylamide gel, which was stained with Coomassie blue. The samples were wild-type PyrR (lane 1), T18A (lane 2), R19Q (lane 3), H22A (lane 4), R27Q (lane 5), T41I (lane 6), R141Q (lane 7), R145Q (lane 8), K152Q (lane 9), and molecular mass standard proteins (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.) with apparent molecular masses in kilodaltons of each indicated by the arrows (lane 10).

TABLE 2.

Physical and functional properties of purified wild-type and mutant PyrR proteins

| PyrR | Physical propertyc

|

Functional property

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native MW from HPLC | % α-helix from CD | Tm (°C) from DSC | UPRTase sp act (μmol/min/mg) | Affinity for pyr mRNA

|

|||

| Kd (no ligand) (nM) | Kd (UMP) (nM) | Kd (UTP) (nM) | |||||

| Wild type | 110,000 | 28 | 50 | 11 ± 0.4 | 3 | 0.7 | 0.02 |

| T18A | 120,000 | 30 | 52 | 14 ± 3.5 | 20 ± 10 | 1 ± 1 | 0.3 ± 0.03 |

| R19Q | >3 × 106 | 16 | —a | 1 ± 0.2 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| H22A | 130,000 | 29 | 66 | 8 ± 1.0 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| R27Q | 95,000b | 33 | 51 | 14 ± 1.3 | 20 ± 20 | 9 ± 9 | 10 ± 5 |

| T41I | >3 × 106 | 25 | —a | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 7 | 20 ± 4 | 8 ± 0.8 |

| R141Q | 120,000 | 26 | 54 | 14 ± 5.8 | 200 ± 40 | 40 ± 20 | 1 ± 1 |

| R146Q | 120,000 | 32 | 57 | 12 ± 0.5 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| K152Q | 88,000b | 35 | 54 | 8 ± 1.6 | 90 ± 2 | 70 ± 6 | 200 ± 100 |

No Tm was observable because of precipitation of the protein during heating.

Molecular weight of the largest peak; some high-molecular-weight protein was also detected.

Abbreviations: MW, molecular weight; CD, circular dichroism; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry.

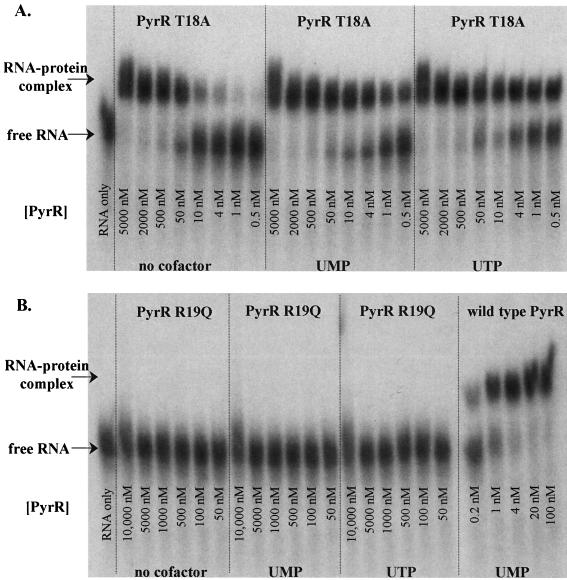

The six mutant PyrR proteins that appeared by all criteria to be folded normally and to possess normal UPRTase activity fell into two classes with respect to their binding to pyr mRNA, which was measured by a gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay using an RNA known to bind with high affinity to wild-type PyrR (2) (Table 2). Some examples of the results of the gel mobility shift analyses are shown in Fig. 2. H22A and R146Q PyrR mutants did not bind detectably to RNA under any conditions tested. We conclude that PyrR residues His-22 and Arg-146 are thus likely to play crucial roles in interaction with RNA. Four of the mutant PyrR proteins exhibited the ability to bind to RNA but bound with reduced affinity and in most cases reduced ability of uridine nucleotides to cause tighter binding of RNA. In order of the increasing severity of their defects, these were T18A, R27Q, R141Q, and K152Q (the latter two had similar defects). Two of these four mutant PyrR proteins, R27Q and K152Q, showed little or no increase in their apparent affinity for RNA upon the addition of UMP or UTP. This might indicate that these proteins have detects in the binding of uridine nucleotides. However, it must also be pointed out that binding of these two PyrR proteins to RNA was the most difficult to reproduce, as seen from the large standard deviations in the apparent dissociation constants. These two proteins also displayed lower-than-normal native molecular weights and a tendency to form high-molecular-weight aggregates on HPLC analysis. Thus, while these mutants appeared from all other criteria to be folded normally, they may have alterations in their subunit-subunit interactions. Two mutant PyrR proteins, T18A and R141Q, did respond to uridine nucleotides but bound to RNA with lower affinity than that of the wild type in all cases. These two mutant proteins identify amino acid residues that are probably involved in RNA binding.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic mobility shift analysis of binding of pyr RNA by wild-type PyrR and PyrR mutants T18A and R19Q. Binding reaction mixtures contained 50 pM 32P-labeled BL2 RNA and the concentrations of PyrR shown. When uridine nucleotides were included, the concentration was 0.5 mM. (A) T18A, a mutant PyrR that displayed moderate defects in RNA binding. (B) R19Q, a mutant PyrR that failed to bind RNA, and wild-type PyrR.

From the studies of purified mutant PyrR proteins we reached the following conclusions. Replacement of His-22 and Arg-146 with Ala and Gln, respectively, caused rather large defects in the ability of PyrR to bind pyr mRNA. Mutation of Thr-18 and Arg-141 yielded smaller but detectable defects in RNA binding. Replacement of Arg-27 and Lys-152 with Gln caused defects in RNA binding, but interpretation of the properties of these mutants is rendered less certain by apparent defects in their subunit-subunit interactions. Purified R19Q and T41I did not have native structures. Further analysis of the results and an attempt to integrate the observations in Tables 1 and 2 are found in the Discussion.

DISCUSSION

From a characterization of 13 PyrR mutants in this work four amino acid residues were identified as likely to be involved directly in binding of the protein to pyr mRNA. Two mutants, H22A and R146Q, had normal physical properties and UPRTase activity when purified but did not bind detectably to RNA. Both pyrR mutants also failed to regulate pyrB normally when they replaced the normal pyrR gene in B. subtilis, even though they were produced at normal levels and had normal UPRTase activity in crude extracts. While it is possible that other substitutions might have led to less severe defects, we conclude that it is likely that His-22 and Arg-146 play major roles in RNA binding by PyrR.

The purified T18A and R141Q PyrR mutants also had normal physical properties and UPRTase activities. Both of these mutant proteins bound to RNA in vitro and bound RNA more tightly in the presence of uridine nucleotides, but binding was significantly weaker than that with wild-type PyrR. The expression and UPRTase activities of these two mutants in single gene copies in B. subtilis cells were normal. The defects in the regulation of the pyr operon by these mutations in pyrR correlated roughly with the observed reduction in the affinity of the mutant PyrR proteins for RNA. We conclude that Thr-18 and Arg-141 probably play roles in RNA binding, although their contributions may be quantitatively smaller than those of His-22 and Arg-146.

Two additional PyrR mutants, R27Q and K152Q, identified residues that are candidates for involvement in RNA binding, but in these cases we cannot be so confident that the mutant proteins are folded normally. Both mutant proteins could be purified by the same techniques as those used for wild-type PyrR. The purified proteins had normal UPRTase specific activities and normal physical properties, except that their behavior on molecular sieving chromatography provided indications of possible abnormalities in subunit-subunit interactions. Regulation of pyrB by B. subtilis strains bearing these pyrR mutations was normal when the cells were grown with excess pyrimidines but modestly deficient when the cells were grown on minimal medium. However, crude extracts of such cells did not contain PyrR with normal UPRTase activity; in fact, K152Q PyrR appeared to be produced at very low levels. These observations do not agree with the normal UPRTase activity of the purified recombinant mutant proteins. The purified R27Q and K152Q PyrR proteins displayed substantial abnormalities in their binding to RNA and little or no response of RNA binding to uridine nucleotides. Thus, there is evidence that Arg-27 and Lys-152 are involved in RNA binding, but this conclusion must be qualified by the possibility that the two mutant proteins had more global physical defects.

The role, if any, in regulation of pyr expression of the six other amino residues in PyrR in which we constructed mutations is much less clear. On the basis of the properties of the R15Q mutant in vivo (Table 1), it appears that Arg-15 is not involved in regulation or RNA binding, but this mutant protein was not purified and characterized. All of the other mutants, R19Q, T41I, H140A, Y149A, and T156I, showed defects in regulation of pyrB expression that ranged from severe to relatively minor. However, because there was evidence for abnormalities in all of these proteins, one cannot be certain that the regulatory defects were not simply an indirect consequence of abnormal protein folding. Even though the recombinant R19Q PyrR could be reconstituted from inclusion bodies into a soluble form, the purified protein clearly did not have native structure. However, when the R19Q pyrR gene was expressed in a single copy in B. subtilis, normal to above-normal amounts of soluble PyrR were expressed that had a normal UPRTase specific activity. Thus, when it was not overexpressed in E. coli, it appeared to fold normally. When R19Q pyrR was expressed in single copy in the B. subtilis ΔpyrR strain, regulation of pyrB was almost totally lost (Table 1). These observations lead us to suggest that Arg-19 does play a role in regulation, although we cannot conclude that it is directly involved in RNA binding.

While there was a rough correspondence between the defects in pyr regulation with the various pyrR mutants and the defects of the corresponding purified mutant PyrR proteins, it was far from exact. The H22A mutant PyrR failed to regulate pyr genes in vivo and failed to bind RNA in vitro. On the other hand, the R141Q pyrR mutant displayed little ability to regulate pyrB, even though the purified protein was able to bind to RNA, albeit with 40- to 50-fold-lower apparent affinity. The purified R146Q PyrR did not bind detectably to RNA at all in the gel shift assay, but the corresponding mutant pyrR gene had residual ability to regulate pyrB, although expression was elevated about 10-fold above the wild-type level. The reduction in apparent affinity for RNA was similar for the R141Q and K152Q mutant PyrR proteins, but the R141Q pyrR mutant displayed a much larger defect in the regulation of pyr genes in vivo than did K152Q. These discrepancies are not surprising. First, as pointed out by Bonner et al. (2), the gel mobility shift assay for RNA binding does not provide true dissociation constants and the apparent affinities may be substantially in error, especially for PyrR-RNA interactions that are weak or characterized by rapid dissociation of the complex during the electrophoretic separation of the complex. Furthermore, regulation of pyrB expression in vivo is the result of a process involving the relative rates of transcription initiation and elongation, RNA folding, and PyrR binding at three distinct attenuation regions. One could hardly expect the sum of these processes to be entirely determined by the apparent affinity of PyrR for a segment of RNA from one of the attenuation regions.

The sites of mutation in this study were chosen from amino acid residues whose side chains were at the surface of a region of PyrR that is characterized by an abundance of positively charged or neutral side chains that have been found previously to interact with RNA in other well-characterized protein-RNA complexes (4). Other surfaces of PyrR are predominantly negatively charged. Both dimeric and hexameric forms of PyrR have been described elsewhere (16). The hexameric form predominates at higher concentrations, but it is believed to be in equilibrium with the dimer (17). The electropositive surface of PyrR that has been proposed as the likely RNA-binding surface is exposed in the dimeric form but forms the inner surface of a relatively small solvent-filled central cavity in the hexameric form that is too small to accommodate the stem-loop RNA structure that PyrR binds (16). For this reason we have assumed that RNA binds to the dimeric form in designing and interpreting our mutagenesis studies. Two reservations must be kept in mind, however. First, Bonner et al. (2) recently reported experiments that indicated that RNA binds to PyrR in a one-to-one molar ratio, so that it is possible that RNA binds to PyrR as a monomer, not the dimer. On the other hand, monomeric PyrR has not been seen in solution, and the crystal structure is consistent with a tightly associated dimer. Second, it is known (2) that UMP and UTP increase the affinity of PyrR for RNA. The only currently available structure for PyrR is that of the unliganded protein, so that it is possible that the disposition of some amino acids is altered in the PyrR-nucleotide complex.

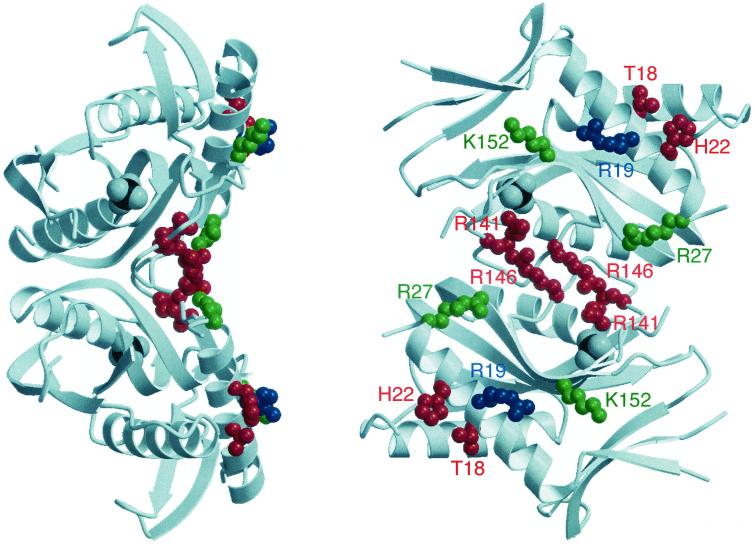

The locations of the side chains of PyrR residues that have been implicated as specifically involved in RNA binding or regulation of attenuation, as discussed above, are mapped onto the dimeric structure of PyrR in Fig. 3. These residues are well distributed over one concave face of the dimeric PyrR molecule. Furthermore, the side chains of all of them except Arg-141 are exposed and accessible for interaction with an RNA molecule. (Thr-18 is at the edge of the putative RNA-binding site and is not pointed into it in the unliganded PyrR structure, but its side chain could hydrogen bond to RNA.) Arg-141 is involved in a network of hydrogen bonds that maintains the structure of the dimer loop (residues 138 to 144) that lies at the interface between monomers along the twofold symmetry axis. This region appears to form the “floor” of the putative RNA-binding surface of PyrR, so that the R141Q mutation may exert its effect by alterations in the overall shape of this region rather than by simple replacement of a side chain that interacts with RNA.

FIG. 3.

Three-dimensional structure of PyrR showing the locations of residues implicated in RNA binding. Two views of the PyrR dimer, rotated by 90° with respect to each other, are shown with the polypeptide rendered as a gray ribbon. Side chains of residues shown in red were strongly implicated in RNA binding, while those shown in green were implicated in RNA binding with the reservation of possible perturbations in subunit interactions. The residue shown in blue was implicated in regulation of pyr expression in vivo, but a direct role in RNA binding was not shown. A sulfate ion in the crystal structure of PyrR occupies the position of the phosphate moiety of nucleoside monophosphates in phosphoribosyltransferases and is rendered with a gray space-filling model. This figure was made with the programs Molscript (9) and Raster3D (11).

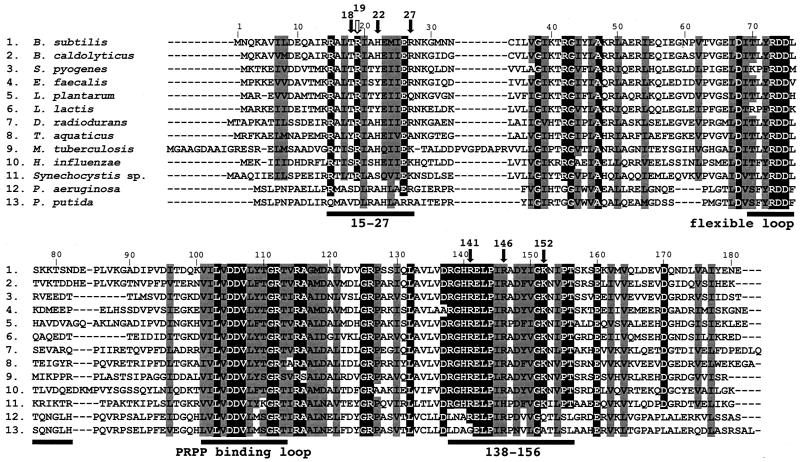

The results of this study do not, of course, fully define the amino acid residues in PyrR that are involved in RNA binding or even define all of the surfaces of the protein that are in intimate contact with pyr RNA. However, our findings are strong evidence in support of the proposal of Tomchick et al. (16) that residues that interact with RNA lie in a face of the dimeric form of PyrR in which positively charged and neutral amino acid side chains predominate in an electrostatic surface potential map. The RNA-binding residues identified in this study are distributed over one face of the PyrR dimer (Fig. 3), but they lie in two short segments of the PyrR sequence, namely, in or adjacent to the dimer loop described above and in another segment, residues 18 to 27, which is found in helix 1 of the protein. It is significant that the sequences of the dimer loop are highly conserved in the PyrR proteins from many diverse bacterial species (Fig. 4). The only exception to this conservation is found with PyrR sequences from Pseudomonas species, in which PyrR does not appear to exert its regulatory function by binding to RNA (G. A. O'Donovan, personal communication). However, the three residues from positions 18 to 27 implicated in RNA binding in this study are not conserved in all of the species compared in Fig. 4. These residues may lie in the RNA-binding surface, so that mutations in them cause defects in RNA binding, but their side chains may not be bonded directly to RNA in a highly specific fashion. Alternatively, in the case of two of these residues, Thr-18 and His-22, the residues replacing them in other species are also capable of hydrogen bonding to RNA. These differences could represent adaptation for binding to the slightly different pyr RNA sequences to which PyrR binds in these species (15).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of PyrR proteins from diverse bacteria. Amino acid residues that are identical in all species or all species except Pseudomonas (see text) are shown as white letters with a black background; amino acid residues that are similar in all or most species are shown in gray shading. Black arrows indicate residues implicated in RNA binding; the white arrow indicates Arg-19, which was implicated in regulation, but not directly in RNA binding. PRPP, 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate.

A much more detailed picture of the interaction between PyrR and RNA will require a high-resolution structure of this complex. So far, only the structure of unliganded PyrR from B. subtilis has been obtained (16). Attempts to crystallize the complex are in progress.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Diana Tomchick and Janet Smith, Purdue University, for valuable discussions of the structure of PyrR and Janet Smith for assistance with the preparation of Fig. 3, Mark Lies for assistance with HPLC analysis, Kara Weiss for assistance with differential calorimetry, and Ana Jonas and her colleagues for assistance with circular dichroism measurements.

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant GM47112 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bond, R. W., A. S. Field, and R. L. Switzer. 1983. Nutritional regulation of degradation of aspartate transcarbamylase and of bulk protein in exponentially growing Bacillus subtilis cells. J. Bacteriol. 153:253-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner, E. R., J. N. D'Elia, B. K. Billips, and R. L. Switzer. 2001. Molecular recognition of pyr mRNA by the Bacillus subtilis attenuation regulatory protein, PyrR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:4851-4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, Y.-H., J. T. Yang, and H. Martinez. 1972. Determination of the secondary structures of proteins by circular dichroism and optical rotatory dispersion. Biochemistry 11:4120-4131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Draper, D. E. 1999. Themes in RNA-protein recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 293:255-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghim, S.-Y., and R. L. Switzer. 1996. Characterization of cis-acting mutations in the first attenuator region of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon that are defective in regulation of expression by pyrimidines. J. Bacteriol. 178:2351-2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghim, S.-Y., and R. L. Switzer. 1996. Mutations in Bacillus subtilis PyrR, the pyr regulatory protein with defects in regulation by pyrimidines. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 137:13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grandoni, J. A., S. B. Fulmer, V. Brizzio, S. A. Zahler, and J. M. Calvo. 1993. Regions of the Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon involved in regulation by leucine. J. Bacteriol. 175:7581-7593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikuta, N., B. N. Souza, F. F. Valencia, M. E. B. Castro, A. C. G. Schenberg, A. Pizzirani-Kleiner, and S. Astolfi-Filho. 1990. The α-amylase gene as a marker for gene cloning: direct screening of recombinant clones. Bio/Technology 8:241-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraulis, P. 1991. Molscript. A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu, Y., R. J. Turner, and R. L. Switzer. 1995. Roles of the three transcriptional attenuators of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic operon in the regulation of its expression. J. Bacteriol. 177:1315-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merritt, E. A., and D. J. Bacon. 1997. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277:505-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 13.Prescott, L. M., and M. E. Jones. 1969. Modified methods for the determination of carbamyl aspartate. Anal. Biochem. 32:408-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinmetz, M., and R. Richter. 1994. Plasmids designed to alter the antibiotic resistance expressed by insertion mutations in Bacillus subtilis through in vivo recombination. Gene 142:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Switzer, R. L., R. J. Turner, and Y. Lu. 1999. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic operon by transcriptional attenuation: control of gene expression by an mRNA-binding protein. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 62:329-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomchick, D. R., R. J. Turner, R. L. Switzer, and J. L. Smith. 1998. Adaptation of an enzyme to regulatory function: structure of Bacillus subtilis PyrR, a bifunctional pyr RNA-binding attenuation protein and uracil phosphoribosyltransferase. Structure 6:337-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner, R. J., E. R. Bonner, G. K. Grabner, and R. L. Switzer. 1998. Purification and characterization of Bacillus subtilis PyrR, a bifunctional pyr mRNA-binding attenuation protein/uracil phosphoribosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5932-5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner, R. J., Y. Lu, and R. L. Switzer. 1994. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic (pyr) gene cluster by an autogenous transcriptional attenuation mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 176:3708-3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiener, M. P., T. Gackstetter, G. L. Costa, J. C. Bauer, and K. A. Kretz. 1995. Recent advances in PCR methodology, p. 11-24. In A. M. Griffin and H. G. Griffin (ed.), Molecular biology: current innovations and future trends. Horizon Scientific Press, Wyndham, Norfolk, United Kingdom.