Abstract

Strains of Caulobacter crescentus elaborate an S-layer, a two-dimensional protein latticework which covers the cell surface. The S-layer protein (RsaA) is secreted by a type I mechanism (relying on a C-terminal signal) and is unusual among type I secreted proteins because high levels of protein are produced continuously. In efforts to adapt the S-layer for display of foreign peptides and proteins, we noted a proteolytic activity that affected S-layer monomers with foreign inserts. The cleavage was precise, resulting in fragments with an unambiguous N-terminal sequence. We developed an assay to screen for loss of this activity (i.e., presentation of foreign peptides without degradation), using transposon and traditional mutagenesis. A metalloprotease gene designated sap (S-layer-associated protease) was identified which could complement the protease-negative mutants. The N-terminal half of Sap possessed significant similarity to other type I secreted proteases (e.g., alkaline protease of Pseudomonas aeruginosa), including the characteristic RTX repeat sequences, but the C-terminal half which normally includes the type I secretion signal exhibited no such similarity. Instead, there was a region of significant similarity to the N-terminal region of RsaA. We hypothesize that Sap evolved by combining the catalytic portion of a type I secreted protease with an S-layer-like protein, perhaps to associate with nascent S-layer monomers to “scan” for modifications.

The gram-negative bacterium Caulobacter crescentus elaborates a paracrystalline protein surface (S)-layer which covers the surface of its outer membrane (33-35). The S-layer protein monomer (RsaA; 1,026 amino acids) is secreted by a type I secretion mechanism relying upon a C-terminal secretion signal which is not cleaved during the secretion process (2, 5, 12). Once RsaA is secreted, the S-layer forms by a process of self-assembly into a hexagonal array of about 40,000 interlinked protein monomers per cell (27). Anchoring of RsaA to the cell surface is dependent on a smooth lipopolysaccharide molecule and Ca2+ ions (43) and appears to involve the N-terminal portion of RsaA (5, 6).

The abundance, cell surface location, and geometrical packing of the S-layer protein, as well as properties of C. crescentus itself (ease of genetic manipulation, simple growth requirements, nonpathogenic nature, and biofilm-forming characteristics) have led to the exploitation of the Caulobacter S-layer system for biotechnology applications (36). By constructing gene fusions encoding the C-terminal secretion signal of RsaA linked to sequences encoding a “passenger” protein, the Caulobacter S-layer system has been used for secreting large quantities of hybrid proteins of economic and research interest into culture medium (7). This application has recently become available for general use under the trade name PurePro (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Current research is directed toward optimizing the Caulobacter S-layer system for the surface presentation of large heterologous insertions (50 to 250 amino acids) within the S-layer without adverse affects on S-layer biogenesis (5, 6).

One phenomenon that was noticed early on in the biotechnological development of the Caulobacter S-layer system was the apparent proteolytic cleavage of some RsaA-based hybrid proteins (5, 6). This was observed seemingly for both C-terminal hybrid proteins (i.e., passenger protein linked to the RsaA C terminus) and full-length hybrid proteins (i.e., passenger protein inserted into sites within full-length RsaA). No obvious site specificity was associated with these proteolytic phenomena; apparent cleavages were found between Met and Ser residues and between Phe and Ile residues (5, 6).

Because the proteolytic phenomena described above complicate the use of the C. crescentus S-layer protein secretion system in both biotechnological and research settings, we have been interested in learning more about them. Recently, we found that the smaller proteins seen in preparations of C-terminal hybrid proteins are not the result of proteolytic activity but rather are the result of internal translation initiation following methionyl residues within the passenger portion of the hybrid protein (31). Indeed, at this writing there are no clear instances of proteolytic degradation of C-terminal hybrid S-layer proteins. In other instances, however, where full-length RsaA hybrid proteins are concerned, proteolytic degradation still appears likely, especially in cases where insertion of the same heterologous sequence at different positions yields variable levels of apparent cleavage products which cannot be correlated with internal methionyl residues (6).

This study presents the results of experiments designed to further understand the proteolytic phenomena associated with the synthesis of full-length RsaA hybrid proteins by C. crescentus. We report the identification of a metalloprotease that accounts for the degradation of full-length RsaA hybrid proteins seen thus far and an unusual structural feature: the enzyme possesses a domain sharing sequence similarity with RsaA, the S-layer protein monomer. This latter result suggests a mechanism to specifically target proteolytic activity to RsaA-based hybrid proteins and, by implication, to RsaA itself.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. When appropriate, antibiotics were included in LB medium at the following concentrations: streptomycin (STR), 50 μg/ml; kanamycin (KAN), 50 μg/ml; ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; gentamicin, 30 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | recA endA | Life Technologies |

| S-17 λ pir | recA Smr Kmr carries λ pir prophage | 9 |

| Caulobacter crescentus | ||

| JS4000 | Spontaneous RsaA− mutant of strain CB2 maintained in the laboratory of J. Smit | 32 |

| JS4020 | Strain JS4000 with plasmid pTZ18U::rsaAΔP (485/IHNVG20) integrated into the chromosome | This study |

| JS4021 | Sap− Tn5 mutant of strain JS4020 | This study |

| JS4015 | Sap− UV-NTG mutant of strain JS4000 | This study |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pG8 | Source of IHNV-G gene; Ap | 46 |

| pHP45Ω | Source of the HindIII fragment carrying the Smr gene for construction of pTZ18USm | 11 |

| pHP45Ω-Km | Source of the HindIII fragment carrying the Kmr gene for construction of pBBR1MCS::Kmsap | 11 |

| pAG408 | Suicide vector for Tn5 mutagenesis; ColE1, Gm Km Ap | 38 |

| pBBR1MCS | Broad-host-range cloning and expression vector; Cm | 17 |

| pBSK, pBSKII | Phagemid cloning and expression vectors; ColE1, Ap | Stratagene |

| pUC9CXS | pUC9 (41) with a modified multiple cloning site; Ap, Cm; used to provide DNA fragments with suitable BamHI termini for in-frame insertion into BamHI linker mutated rsaAΔP genes | 5 |

| pTZ18U, pTZ19U | Phagemid versions of pUC18 and pUC19 (45); gene expression driven by E. coli lac promoter; ColE1, Ap | Amersham Life Sciences |

| pTZ18UB | BamHI site of pTZ18U lacking a BamHI site; the BamHI site was destroyed by BamHI digestion, polishing with PoIIK, and religation; Ap | 5 |

| pTZ18USm | pTZ18U with an Smr gene inserted as a PolK-polished HindIII-fragment of the ScaI site of the Apr gene; Sm | This study |

| pTZ18UB::rsaA(AciI485BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at an AciI site corresponding to amino acid 485 of RsaA in pTZ18UB; Ap | 6 |

| pTZ18UB::rsaA(MspI450BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at an MspI site corresponding to amino acid 450 of RsaA in pTZ18UB; Ap | 6 |

| pTZ18UB::rsaA(HinPI723BamHI) | rsaAΔP carrying a BamHI linker insertion at a HinPI site corresponding to amino acid 723 of RsaA in pTZ18UB; Ap | 6 |

| pWB9KSAC | pKT215-derived (3) expression vector incorporating the rsaA promoter; Cm, Sm | 5 |

| pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP | A promoterless version of the rsaA gene (rsaAΔP) in pWB9KSAC; Cm, Sm | 5 |

| pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP(450/Pilin 12) | rsaAΔP carrying a DNA insert encoding 12 amino acids of a P. aeruginosa pilin epitope at a position corresponding to amino acid 450 of RsaA in pWB9KSAC | 6 |

| pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP(723/3X Pilin 12) | rsaAΔP carrying a DNA insert encoding tandem 3 copies of a P. aeruginosa pilin epitope at a position corresponding to amino acid 723 of RsaA in pWB9KSAC | This study |

| pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP(723/VP2C) | rsaAΔP carrying a DNA insert encoding amino acids 145 to 257 of the VP2 glycoprotein of IPNV at a position corresponding to amino acid 723 of RsaA in pWB9KSAC | This study |

| pTZ18UB/pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP(485/IHNVG20) | rsaAΔP carrying a DNA insert encoding 20 amino acids of IHNV-G at a position corresponding to amino acid 485 of RsaA in pTZ18UB or pWB9KSAC | This study |

| pTZ18UB/pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP(450/IHNVG20) | rsaAΔP carrying a DNA insert encoding 20 amino acids of IHNV-G at a position corresponding to amino acid 450 of RsaA in pTZ18UB or pWB9KSAC | This study |

| pTZ18USm::rsaAΔP(485/IHNVG20) | rsaAΔP carrying a DNA insert encoding 20 amino acids of IHNV-G at a position corresponding to amino acid 485 of RsaA in pTZ18USm | This study |

| pBBR1MCS::sap | pBBR1MCS carrying a 2.2-kb HindIII/BamHI sap fragment. The orientation of the fragment allows expression of the sap gene from either its native promoter or the lac promoter of pBBR1MCS; Cm | This study |

| pBBR1MCS::Kmsap | pBBR1MCS::sap carrying an additional 1.5-kb HindIII fragment encoding a Kmr gene; Cm, Km | This study |

C. crescentus was grown at 30°C in peptone-yeast extract (PYE) medium (0.2% peptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.01% CaCl2, 0.02% MgSO4). When appropriate, antibiotics were included in PYE medium at the following concentrations: STR, 50 μg/ml; KAN, 50 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 2 μg/ml. Solidified LB and PYE media were prepared by adding agar to 1.2% (wt/vol).

Recombinant DNA methods.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from C. crescentus by using standard methods (30), while plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli and C. crescentus by using the boiling method (for RSF1010-based plasmids [16]) or the alkaline lysis method (for all other plasmids [8]). Plasmid DNA was routinely introduced into E. coli and C. crescentus by electroporation (13).

DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Life Technologies (Burlington, Ontario, Canada) or New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and were used according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Agarose gel electrophoresis (in a Tris-borate-EDTA buffer) was conducted by standard methods (30); in preparative applications, DNA fragments were purified using QIAEX II (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.).

Southern hybridization was done using standard methods (30) and another methodology (39). DNA samples were electrophoresed in 0.8% agarose gels and probed with oligonucleotides labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham) using the Rediprime II random prime labeling system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

PCR amplification was conducted by using TaqI or Pfx DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) as instructed by the manufacturer and a Techne Progene thermal cycler (Mandel Scientific Co., Guelph, Ontario, Canada).

Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the Nucleic Acid/Protein Service Unit at the University of British Columbia, using double-stranded plasmid template and an ABI Prism 377 automated sequencer. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Nucleic Acid/Protein Service Unit by using a Perkin-Elmer ABI synthesizer.

Isolation of RsaA.

Wild-type RsaA and full-length RsaA hybrid proteins were isolated from C. crescentus cells by low-pH extraction (44) as modified by Nomellini et al. (27). Briefly, mid-log-phase cells (optical density at 600 nm of 1) were washed once in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min) and then resuspended by vortexing in 100 mM HEPES buffer, pH 2.0, in a volume equivalent to 5% of the original culture volume. After 5 min at room temperature, the pH was neutralized with NaOH, cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant fluid containing RsaA was recovered.

SDS-PAGE and Western analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was conducted by the method of Laemmli (19); samples were treated at 37°C, rather than boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer prior to electrophoresis (32). Western immunoblot analysis was carried out as described by Walker et al. (43) using an anti-RsaA polyclonal antibody as a probe, secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase, and color-forming reagents.

Western colony immunoblotting (6) was performed by spread plating cells to a density of 100 to 200 CFU per standard petri plate. Following incubation for 3 to 4 days at 30°C, nitrocellulose membranes were pressed onto the surface of the plates for 2 min. The membranes with adherent colonial material were then lifted off, allowed to air dry for 5 to 10 min, treated with 5% skim milk, and processed in the standard fashion for Western transfers of SDS-PAGE gels.

Amino-terminal sequence determination.

Protein samples for N-terminal sequencing were electrophoretically transferred from SDS-PAGE gels to a 0.2-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) by using a Bio-Rad transfer apparatus as described by the manufacturer. The membrane was briefly stained in Coomassie blue R-250 (Sigma), destained in 50% methanol, and air dried. The desired protein band was excised from the membrane by using a scalpel, and the N-terminal amino acid sequence was obtained by automated Edman degradation.

Tn5 mutagenesis of C. crescentus JS4020.

C. crescentus strain JS4020 was constructed by electroporating a sample of plasmid pTZ18USm::rsaΔP(485/IHNVG20) into strain JS4000 (Sms RsaA−). The resulting cell suspension was plated on solid PYE medium containing 50 μg of STR/ml to select for cells containing the chromosomally integrated plasmid resulting from a single crossover event between the plasmid-borne copy of rsaA and the chromosomal copy of rsaA in strain JS4000. Smr cells from several colonies were then screened by low-pH extraction for the presence of cell-surface-bound S-layer protein fragments characteristic of proteolytic cleavage within the infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus glycoprotein (IHNV-G) insert as well as proteolytic cleavage within the RsaA N terminus (the proteolytic phenotype). One isolate exhibiting both STR resistance and the expected proteolytic phenotype was retained and designated strain JS4020.

Conjugation was used to introduce a Tn5 derivative carried by the suicide vector pAG408 into C. crescentus JS4020. One hundred microliters of an overnight culture of E. coli S-17 λ pir(pAG408) was mixed with 1 ml of an early-log-phase culture of JS4020 in 5 ml of 10 mM MgSO4. The cell mixture was collected on a sterile 22-mm-diameter nitrocellulose filter paper, and the filter paper was placed on the surface of PYE agar in a petri dish. After overnight incubation at 30°C, the cells were dislodged from the filter in 5 ml of 10 mM MgSO4, and 100-μL aliquots were plated on PYE agar containing KAN and STR.

UV-NTG mutagenesis of C. crescentus JS4000.

A mutant pool of strain JS4000 previously created by UV light mutagenesis (29) was further mutagenized using nitrosoguanidine (NTG) by the method of Miller (23).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sap gene nucleotide sequence has been submitted to GenBank (accession no. AF193064).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RsaA molecules carrying IHNV-G peptide inserts are subjected to proteolysis.

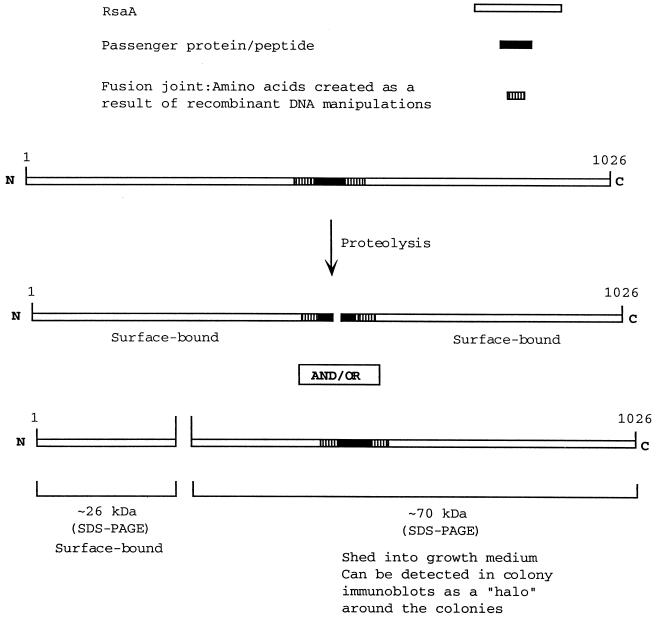

In previous work (6), it was noted that insertion of a 12-amino-acid peptide derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin at centrally located positions in the RsaA primary sequence often resulted in the proteolytic cleavage of the hybrid protein within the pilin-peptide insert and/or at a fixed site distant from the insertion site within the N terminus of RsaA. Cleavage within the pilin peptide insert yielded two fragments which remained bound to the cell surface, while cleavage within the RsaA N terminus yielded a 26-kDa N-terminal cleavage product which remained surface bound and a C-terminal fragment which was released into the growth medium (Fig. 1). Because the 26-kDa N-terminal portion of RsaA remained surface bound, this region of protein is presumed to be involved in anchoring the protein to the cell surface. For the purposes of this study, cells exhibiting these specific proteolytic phenomena are said to possess the proteolytic phenotype.

FIG. 1.

The proteolytic phenotype. Proteolytic phenomena identified by Bingle et al. (6) which are associated with the synthesis of RsaA molecules carrying 26-amino-acid inserts largely derived from P. aeruginosa pilin.

In order to confirm that the proteolytic phenotype was not associated with pilin peptide inserts alone, we studied the effect of inserting a 20-amino-acid peptide (ASESREELLEAHAEIISTNS) derived from amino acids 306 to 325 of the IHNV-G into two previously identified sites: amino acids 485 and 450 in RsaA. This was done as part of efforts to produce vaccines against the salmonid fish virus IHNV (31). The IHNV-G DNA insert was synthesized using PCR, inserted into rsaAΔP, and introduced into the RsaA− strain JS4000 by using the C. crescentus expression plasmid pWB9KSAC with methods identical to those described for pilin peptide DNA by Bingle et al. (6).

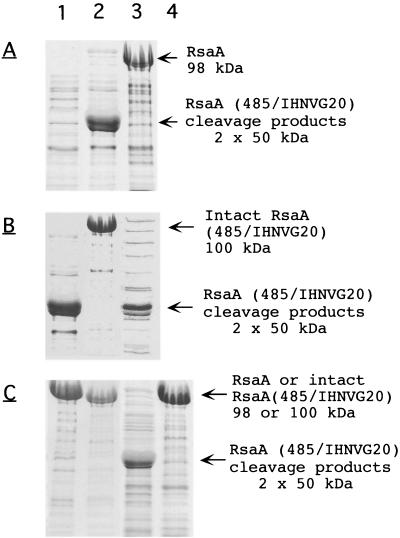

Despite the difference in the composition of the insert, RsaA hybrid proteins carrying IHNV-G peptide insertions exhibited the same proteolytic phenotype (Fig. 1) as cells synthesizing RsaA molecules carrying pilin peptide inserts. Insertion of the 20-amino-acid IHNV-G peptide at either amino acid 485 or 450 resulted in the cleavage of the hybrid protein, yielding two fragments with molecular masses consistent with proteolytic cleavage within the IHNV-G insert as well as the 26-kDa fragment (Fig. 1 and 2A). Native RsaA was not subject to proteolytic cleavage (Fig. 2A).

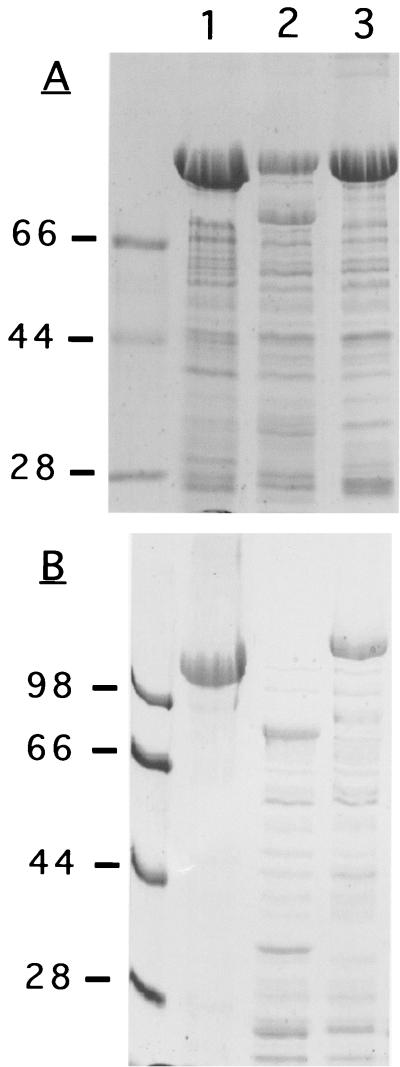

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of RsaA (485/IHNVG20) synthesized by Sap+ and Sap− strains of C. crescentus. The protein was extracted from the cell surface by the low-pH method. The region of the gels containing the 26-kDa fragment is not shown. (A) Proteolytic cleavage of RsaA and RsaA (485/IHNVG20) in Sap+ JS4000. Lanes: 1, low-pH extract of JS4000; 2, low-pH extract of (pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP[485/IHNVG20]); 3, low-pH extract of JS4000(pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP). (B) Proteolytic cleavage of RsaA (485/IHNVG20) in Sap+ JS4020 and Sap− Tn 5 mutant JS4021. Lanes: 1, JS4020; 2, JS4021; 3, JS4021(pBBR1MCS::Km sap). (C) Complementation of the UV-NTG mutation in Sap− JS4015 cells containing either pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP or pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP(485/IHNVG20). Lanes: 1, cleavage of RsaA (485/IHNVG20) in Sap− JS4015; 2, cleavage of RsaA in Sap− JS4015; 3, cleavage of RsaA (485/IHNVG20) in Sap+ JS4015(pBBR1MCS::Km sap); 4, cleavage of RsaA in Sap+ JS4015(pBBR1MCS::sap).

To identify the precise cleavage site, the cleavage products derived from RsaA (450/IHNVG20) were subjected to N-terminal sequencing. Like RsaA molecules carrying pilin peptide insertions (6), cleavage of RsaA (450/IHNVG20) also occurred within the heterologous insert, in this case between an Arg and a Ser residue encoded by the 3′ fusion joint DNA between the IHNV-G and rsaA DNA (Fig. 1).

Tn5 mutagenesis of C. crescentus JS4020.

C. crescentus strain JS4020 was used as a background to detect the loss of the proteolytic phenotype resulting from Tn5 mutagenesis. This strain possessed a chromosomal copy of rsaA carrying a DNA insert encoding the 20-amino-acid IHNV-G peptide at the site corresponding to RsaA amino acid 485. The creation of this mutant is described in Materials and Methods.

To screen for the loss of the proteolytic phenotype following Tn5 mutagenesis, a colony immunoblot assay was used. When proteolytic cleavage of an RsaA hybrid protein occurs at the N-terminal site (distant from the site of the heterologous insertion), most of the C-terminal cleavage product fragment is released from the cell surface. In colony immunoblots probed with RsaA antibody, this shed RsaA fragment yields an immunoreactive halo around colonies (see Bingle et al. [6] for examples). It was expected that if Tn5 mutagenesis led to the loss of the proteolytic phenotype, this could be detected by screening for halo loss around colonies of JS4020 in colony immunoblots.

To this end, Tn5 mutagenesis of JS4020 was conducted and the resulting mutants were subjected to colony immunoblot assays. To confirm the loss of the proteolytic phenotype and to screen out Tn5 insertions in rsaA (and components of its secretion apparatus), cells from colonies showing halo loss were further screened for the presence of undegraded RsaA (485/IHNVG20) by using the low-pH extraction method coupled with SDS-PAGE. Three mutants exhibiting the loss of the proteolytic phenotype were isolated.

To isolate chromosomal DNA flanking the Tn5 insertion site, chromosomal DNA was prepared from all three mutants, digested with BamHI and BglII, and subjected to Southern analysis using the 1.5-kb KpnI (Tn5) fragment from pAG408 as a probe. Because the Tn5 derivative in pAG408 possesses single BamHI and BglII sites which occur at opposite ends of Tn5, it was expected that single DNA fragments would result from digestion of the Tn5-interrupted chromosomal DNA with either BamHI or BglII separately, but together the two fragments would include, in addition to Tn5, the 5′ and 3′ portions of the interrupted region.

Nucleotide sequencing of DNA flanking the Tn5 insertion site.

Initial nucleotide sequence information from the DNA immediately flanking the Tn5 insertion site was used to search the nucleotide sequence of the C. crescentus CB15 genome as determined by a group at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) (26).

As a result, a 1,977-bp open reading frame (initiating with GTG) encoding a putative 658-residue protein (gene CC0746; accession no. AE005750) was identified which when translated exhibited significant sequence similarity to several metalloproteases, most notably that from P. aeruginosa (a more complete comparison is given below). This result was taken as presumptive evidence that in at least one of the three mutants, Tn5 had inserted into a gene encoding a proteolytic enzyme; this result had obvious relevance to the study at hand. Hereafter, we refer to the gene for the metalloprotease by the designation sap (surface array protease).

Although the nucleotide sequence of the sap gene determined by the TIGR group was derived from analysis of the C. crescentus CB15 genome and our study concerns C. crescentus CB2A JS4000, there were no differences between the genes of the two strains in the initial sequence obtained, indicating that the two protease genes were likely to be nearly identical at the nucleotide sequence level and that the TIGR sequence could be used as a guide to complete the nucleotide sequencing of the DNA flanking the Tn5 insertion site. In addition, this sequence comparison revealed the orientation of the Tn5 insertion and that the insertion site was located almost exactly in the center of the sap gene, with approximately 1,000 bp flanking the insertion site. Using this information and the TIGR sequence as a guide to suitable restriction sites, the nucleotide sequence flanking the Tn5 insertion in one of the three mutants was assembled and submitted to GenBank (accession no. AF193064).

Nucleotide sequence of sap and predicted amino acid sequence of its gene product.

The nucleotide sequence of the JS4000 sap gene (this study) differed by only 2 bp from that reported by Nierman et al. (26) for strain CB15. Both sequences predict a primary translation product of 658 amino acyl residues, but the sequence for the JS4000 gene indicated a valyl residue at position 217 while the nucleotide sequence of the CB15 sap gene predicts an alanyl residue. Thus, the sap gene and Sap protein for these strains are, for practical purposes, interchangeable. The congruence between the sap nucleotide sequences of strains JS4000 and CB15 extended both upstream into a putative gene encoding an OmpA-like protein and downstream into a GC-rich region with the potential to code for a stem-loop structure (5′-AGGGCGGGCGGCCCTCCCCCGAAAAGGTCGCCGCCCGAGTT-3′). Indeed, these regions of DNA exhibited 100% nucleotide sequence identity between the two strains. A potential −35 transcription initiation signal (5′-TTGTCG-3′) and a potential translation initiation signal (5′-GGAG-3′) characteristic of C. crescentus housekeeping genes (22) were also identified in these regions of both strains.

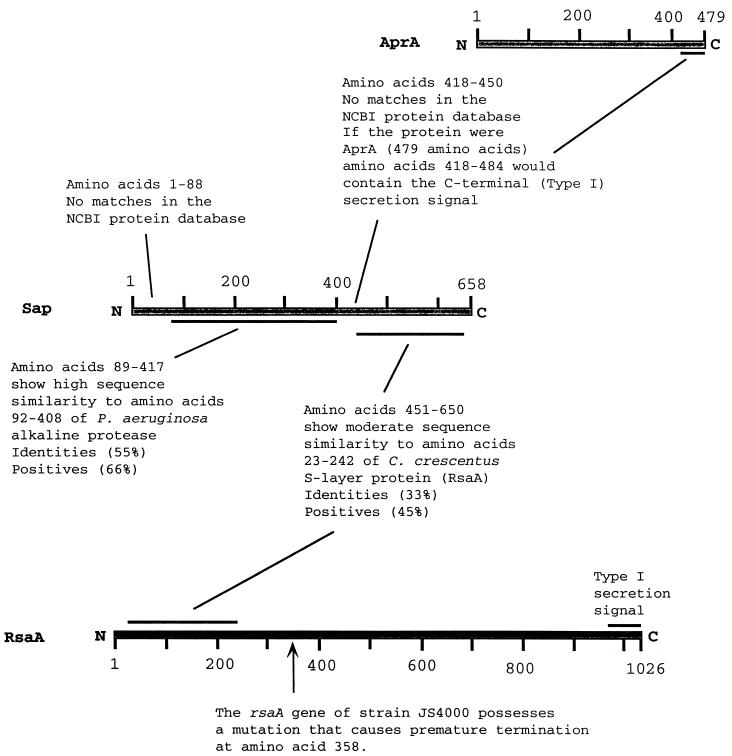

Similarities between Sap and other proteins.

The predicted amino acid sequence of Sap could be divided into two regions, each of which showed similarity to other proteins in the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) protein database (Fig. 3). The similarities were identified using the BLAST algorithm in conjunction with the default parameters (1).

FIG. 3.

Overview of amino acid sequence similarities between Sap, AprA, and RsaA. Although strain JS4000 synthesizes a mutant C-terminally truncated RsaA protein, the amino acid sequence of this molecule is identical to the corresponding regions of the CB15 and NA1000 wild-type RsaA proteins.

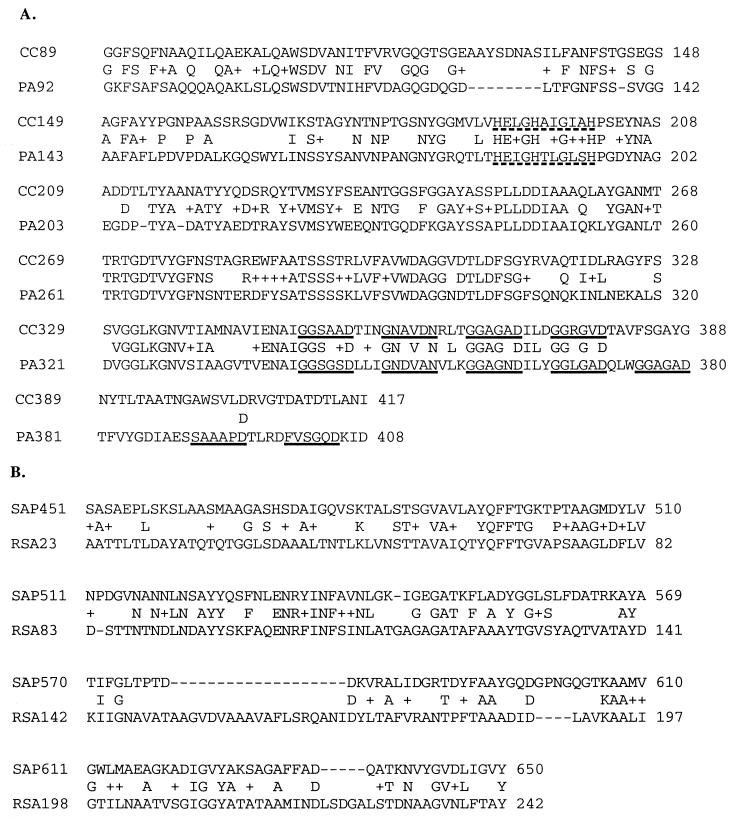

The N-terminal region of Sap exhibited sequence similarity to the alkaline metalloprotease (AprA) of P. aeruginosa (and other members of this family of proteases). This region of the protein contained the metalloprotease active-site consensus sequence (HEXXHXUGUXH) as well as four of the seven Ca2+-binding consensus sequences (GGXGXD) identified in AprA (4), also known as RTX sequences (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

(A) Amino acid sequence similarity comparison between Sap from C. crescentus JS4000 (CC) and the alkaline metalloprotease (AprA) of P. aeruginosa (PA). The sequences underlined with dashed lines indicate the active-site consensus sequence HEXXHXUGUXH, in which X represents an arbitrary amino acid and U is a bulky hydrophobic residue (4). The sequences underlined with solid lines indicate Ca+2 binding sites in the two proteins (consensus sequence GGXGXD). (B) Amino acid sequence similarity between Sap and the S-layer proteins (RsaA) of C. crescentus strains JS4000, NA1000, and CB15. Although strain JS4000 synthesizes a mutant C-terminally truncated RsaA protein, the amino acid sequence of this molecule is identical to the corresponding regions of the CB15 and NA1000 wild-type RsaA proteins.

The C-terminal region of Sap exhibited sequence similarity to the N-terminal region of the C-terminally truncated mutant S-layer protein of C. crescentus JS4000 (37) as well as to the N-terminal region of the wild-type S-layer proteins from C. crescentus strains CB15 (26) and NA1000 (12) (Fig. 3 and 4). In fact, no other amino acid sequence in the NCBI protein database showed any significant degree of sequence similarity to the C-terminal region of Sap except for the N-terminal regions of these three C. crescentus S-layer proteins. The E-value for this alignment was 2 × 10−20, while the closest other aligned homologue was a Drosophila protein with an inconsequential E-value of 4.7.

Two regions of the predicted Sap amino acid sequence showed little or no similarity to sequences in the NCBI protein database: the extreme N terminus (amino acids 1 to 88) and the region covering amino acids 418 to 450 (Fig. 3 and 4). The region analogous to amino acids 418 to 450 in AprA contains information important for efficient secretion of the enzyme by a type I secretion system (12). The extreme N-terminal region of Sap lacks a predicted signal leader peptide (25), and a search of the amino acid sequence for predicted transmembrane domains (15, 42) yielded no significant results. These results indicate that Sap is likely localized to the cytoplasm.

We propose that Sap arose by adaptation of a type I secreted protease similar to AprA of P. aeruginosa. This adaptation was accomplished by the loss of the C-terminal region of the protease, which included the secretion signal, and the acquisition of a portion of an ancestral version of the N-terminal region of the S-layer monomer. The former modification ensured that the protease was retained within the cell. We predict that the latter modification resulted in acquisition of a region of an S-layer monomer that is involved with the interactions between RsaA monomers which normally occur outside the cell during spontaneous S-layer assembly. This enabled the protease to remain associated with the newly synthesized S-layer monomer, thus selectively targeting S-layer monomers as the exclusive substrate of the protease. Whether Sap can associate directly with the RsaA protein is still speculative, but we submit that, given the S-layer specific nature of the protease, this is a reasonable supposition. Additional studies are required to confirm that a protein-protein interaction does occur between these proteins.

The suggestion that Sap is derived from a type I secreted protease like AprA seems justified with the present findings, given the high amino acid similarity to such proteases, the precise conservation of the active site, and the retention of the repeated RTX motifs (4, 10, 28). It is also interesting that from a kinetic standpoint, AprA most readily cleaves C-terminally to Arg and Phe residues (21), precisely the cleavages we have observed for Sap in our studies. Type I secreted proteases are typically secreted as zymogens requiring N-terminal processing and Ca2+ binding in the environment for activity (20, 24). It appears, however, that Sap is a cytoplasmic protein, which raises the question of how it is able to function. That is, we presume that caulobacters, like other bacteria, have little or no intracellular Ca2+. Further study of the Sap protease and its cellular location will resolve this issue.

Isolation and characterization of a sap mutant, JS4015, from a UV-NTG mutant library of JS4000.

Because of the biotechnological relevance of a Sap− mutant, we wanted to create such a mutant lacking a Tn5 insertion. In order to create a Sap− mutant lacking a Tn5 insertion, cells contained in a pool of UV-NTG- mutagenized JS4000 cells were transformed with pWB9KSAC::rsaA(485/IHNVG20) and screened for loss of the proteolytic phenotype (Fig. 2B). Screening of approximately 20,000 colonies resulted in the identification of three mutants lacking this phenotype, one of which was selected and designated JS4015.

Complementation analysis was used to confirm that the UV-NTG-induced mutation in JS4015 was located in the sap gene. JS4015 containing pWB9KSAC::rsaA(485/IHNVG20) was transformed with pBBR1MCS::Km sap (a broad-host-range plasmid compatible with pWB9KSAC) carrying a PCR-amplified copy of the sap gene from JS4000. The PCR primers were chosen to amplify a sequence 140 bp upstream and downstream of the sap coding region; thus, the PCR product was expected to contain the native promoter of the sap gene. When pBBR1MCS::Km sap was introduced into JS4015(pWB9KSAC::rsaA[485/IHNVG20]), the proteolytic phenotype was restored (Fig. 2C), providing strong evidence that JS4015 did indeed possess a mutation in the sap gene. As expected, the Tn5 mutation in strain JS4020 could also be complemented in the same way using pBBR1MCS::sap. A preliminary sequence analysis of PCR-amplified DNA from the JS4015 sap gene has indicated several scattered base changes that we ascribe to the combined NTG and UV mutagenesis. Of particular interest to us is a change of two adjacent bases resulting in the substitution of a lysyl residue for Val188 very near the protease active site, which may well account for the loss of protease activity.

To ensure that the phenotype of Sap− JS4015 was not simply related to the IHNV-G insertions, we tested several other full-length RsaA hybrid protein constructs known to be affected by degradation phenomena; the results for two of these constructs are shown in Fig. 5. In both instances (as well as all others tested so far [J. F. Nomellini, I. Dorocicz, and J. Smit, unpublished data]), significant degradation occurred in a wild-type host (JS4000) while none was detected in the Sap− JS4015 strain.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of RsaA and RsaA carrying large heterologous inserts synthesized by Sap+ strain JS4000 and Sap− strain JS4015. The proteins were extracted from the cell surface using the low-pH method. (A) RsaA with the insertion of a threefold-tandemly repeated P. aeruginosa pilin epitope. A threefold tandem repeat of the pilin tip adhesin epitope from a type IV pilus of P. aeruginosa was prepared and inserted at a position in rsaA corresponding to amino acid 723 of RsaA, using methods previously described (Umelo-Njaka et al. [40]). The total length of this insertion was 134 amino acids. Lanes: 1, JS4000 (pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP) (a no-insertion control); 2, JS4000 (pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP [723/3X Pilin12]); 3, JS4015(pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP [723/3XPilin12]). (B) RsaA with the insertion of a salmonid virus glycoprotein segment. A 112-amino acid segment of the VP2 surface glycoprotein of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) strain SP (14) was prepared by reverse transcriptase-mediated PCR, using genomic RNA derived from the virus. The segment was inserted at a position corresponding to amino acid 723 of RsaA, using methods similar to those described by Bingle et al. (5) and Simon et al. (31) for the insertion of IHNV-G amino acid sequences into RsaA. Lanes: 1, JS4000(pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP); 2, JS4000(pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP [723/VP2C]); 3, JS4015(pWB9KSAC::rsaAΔP [723/VP2C]).

Although the mutational alteration in the sap gene of JS4015 abolished the proteolytic phenotype as defined above, the degradation of the C-terminally truncated mutant S-layer protein synthesized by this strain remained unaffected. As indicated in Table 1, the parent strain of JS4015 is RsaA− strain JS4000. JS4000 does not synthesize a complete S-layer protein. This is due to a single-nucleotide deletion mutation in the third position of codon 358 (Gln) of rsaA, resulting in the creation of a threonine codon followed by a termination codon (2) and the synthesis of a C-terminally truncated S-layer protein of 358 amino acids (Fig. 5). Because this shortened protein lacks a native C terminus and therefore a type I secretion signal, it cannot be secreted. Nevertheless, it has never been detected by Western analysis of whole-cell lysates of JS4000, indicating that this secretion-incompetent molecule is subjected to proteolytic degradation. This degradation seems to be specific to Caulobacter. When the JS4000 rsaA gene encoding the 358-amino-acid truncated S-layer protein was expressed from the pUC19 lacZ promoter in E. coli DH5α, inclusion bodies were formed and a 40-kDa protein immunoreactive with anti-RsaA antibody could be detected in preparations of total cell proteins (W. H. Bingle and J. Smit, unpublished data).

Concluding remarks.

We identified Sap on the basis of its action on RsaA hybrid proteins possessing heterologous insertions. The function of Sap in wild-type C. crescentus synthesizing unmodified RsaA molecules is obscure, based on laboratory growth conditions. Since RsaA molecules carrying heterologous inserts are nontoxic in a Sap− background and the varied cleavage products are secreted from the cell in Sap+ strains (even the N-terminal fragments no longer covalently attached to a secretion signal), it is difficult to readily assign the function of Sap as part of a reclamation system for structurally defective RsaA molecules or to prevent the plugging of the RsaA secretion apparatus by secretion-incompetent RsaA molecules. It may be, however, that under environmental conditions errors in sequence tend to slow secretion, leading to gaps in surface coverage. This may be deleterious at low growth rates in the presence of parasitic bacteria (18) or lytic enzymes, leading to genetic pressure to evolve and retain such a protease.

Regardless of the function of Sap in a wild-type background, the biotechnology aspects of this study are worth considering. The C. crescentus S-layer offers an opportunity for development of a peptide or protein display system capable of displaying heterologous amino acid sequences at a density of 40,000 copies per cell. Display libraries, whole-cell vaccines, and sorbants for binding of organic or inorganic toxic agents are among the possible applications. The identification of sap and its subsequent inactivation now have improved the likelihood that heterologous insertions will be presented efficiently in the S-layer of C. crescentus. We believe the C. crescentus display system, particularly in the strain JS4015 background, will be a useful addition to the repertoire of microorganisms rendered suitable for protein display applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy Smith for technical assistance in the Tn5 mutagenesis experimentation. We also thank William W. Kay and Sharon Gauthier for providing IPNV SP viral RNA.

This work was supported by grants to J.S. from the Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awram, P., and J. Smit. 1998. The Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline S-layer protein is secreted by an ABC transporter (type I) secretion apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 180:3062-3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagdasarian, M., R. Lurz, B. Ruckert, F. C. H. Franklin, M. M. Bagdasarian, J. Frey, and K. N. Timmis. 1981. Specific purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad-host-range, high-copy-number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and host vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene 16:237-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann, U., S. Wu, K. M. Flaherty, and D. B. McKay. 1993. Three-dimensional structure of the alkaline protease of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a two domain protein with a calcium binding parallel beta roll motif. EMBO J. 12:3357-3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingle, W. H., J. F. Nomellini, and J. Smit. 1997. Linker mutagenesis of the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein. Toward a definition of an N-terminal anchoring region and a C-terminal secretion signal and the potential for heterologous protein secretion. J. Bacteriol. 179:601-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingle, W. H., J. F. Nomellini, and J. Smit. 1997. Cell-surface display of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain K pilin peptide within the paracrystalline S-layer of Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 26:277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingle, W. H., J. F. Nomellini, and J. Smit. 2000. The secretion signal of the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein is located within the C-terminal 82 amino acids of the molecule. J. Bacteriol. 182:3298-3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Lorenzo, V., S. Fernandez, M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Engineering of alkyl- and haloaromatic-responsive gene expression with mini-transposons containing regulated promoters of biodegradative pathways of Pseudomonas. Gene 130:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duong, F., A. Lazudunski, B. Cami, and M. Murgier. 1992. Sequence of a cluster of genes controlling synthesis and secretion of alkaline protease in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationships to other secretory pathways. Gene 121:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellay, R., J. Frey, and H. Krisch. 1987. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 52:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilchrist, A., J. Fisher, and J. Smit. 1992. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the gene encoding the Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline surface layer protein. Can. J. Microbiol. 38:193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilchrist, A., and J. Smit. 1991. Transformation of freshwater and marine caulobacters by electroporation. J. Bacteriol. 173:921-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heppell, J., L. Berthiaume, F. Corbin, E. Tarrab, J. Lecomte, and M. Arella. 1993. Comparison of amino acid sequences deduced from a cDNA fragment obtained from infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) strains of different serotypes. Virology 195:840-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann, K., and W. Stoffel. 1993. TMbase. A database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes, D. S., and M. Quigley. 1981. A rapid boiling method for the preparation of bacterial plasmids. Anal. Biochem. 114:193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovach, M. E., R. W. Phillips, P. H. Elzer, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1994. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques 16:800-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koval, S. F., and S. H. Hynes. 1991. Effect of paracrystalline protein surface layers on predation by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. J. Bacteriol. 173:2244-2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilie, H., W. Haehnel, R. Rudolph, and U. Baumann. 2000. Folding of a synthetic beta-roll protein. FEBS Lett. 470:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louis, D., J. Bernillon, and J. M. Wallach. 1998. Use of a 49-peptide library for qualitative and quantitative determination of pseudomonal serralysin specificity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31:1435-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malakooti, J., S. P. Wang, and B. Ely. 1995. A consensus promoter sequence for Caulobacter crescentus genes involved in biosynthetic and housekeeping functions. J. Bacteriol. 177:4372-4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller, J. F. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Miyajima, Y., Y. Hata, J. Fukashima, S. Kawamoto, K. Okuda, Y. Shibano, and K. Morihara. 1998. Long-range effect of mutation of calcium binding aspartates on the catalytic activity of alkaline protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biochem. 123:24-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Søren Brunak, and G. von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nierman, W. C., T. V. Feldblyum, M. T. Laub, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, J. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, et al. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4136-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomellini, J. F., S. Kupcu, U. B. Sleytr, and J. Smit. 1997. Factors controlling in vitro recrystallization of the Caulobacter crescentus paracrystalline S-layer. J. Bacteriol. 179:6349-6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuda, K., K. Morihara, Y. Atsumi, H. Takeuchi, S. Kawamoto, H. Kawasaki, K. Suzuki, and J. Fukushima. 1990. Complete nucleotide sequence of the structural gene for alkaline proteinase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa IFO 3455. Infect. Immun. 58:4083-4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong, C., M. L. Y. Wong, and J. Smit. 1990. Attachment of the adhesive holdfast organelle to the cellular stalk of Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 172:1448-1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd. ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Simon, B., J. F. Nomellini, P. Chiou, W. H. Bingle, J. F. Thornton, J. Smit, and J.-A. Leong. 2001. Recombinant vaccines against infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus: production by the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein secretion system and evaluation in laboratory trials. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 44:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smit, J., and N. Agabian. 1984. Cloning of the major protein of the Caulobacter crescentus periodic surface layer: detection and characterization of the cloned peptide by protein expression assays. J. Bacteriol. 160:1137-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smit, J., and N. Agabian. 1982. Cell surface patterning and morphogenesis: biogenesis of a periodic surface array during Caulobacter development. J. Cell Biol. 95:41-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smit, J., D. A. Grano, R. M. Glaeser, and N. Agabian. 1981. Periodic surface array in Caulobacter crescentus: fine structure and chemical analysis. J. Bacteriol. 146:1135-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smit, J., H. Engelhardt, S. Volker, S. H. Smith, and W. Baumeister. 1992. The S-layer of Caulobacter crescentus: three-dimensional image reconstruction and structure analysis by electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 174:6527-6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smit, J., C. Sherwood, and R. F. B. Turner. 2000. Characterization of high density monolayers of the biofilm bacterium Caulobacter crescentus: evaluating prospects for developing immobilized cell bioreactors. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:339-349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stahl, D. A., R. Key, B. Flesher, and J. Smit. 1992. The phylogeny of marine and freshwater caulobacters reflects their habitat. J. Bacteriol. 174:2193-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suarez, A., A. Guttler, M. Stratz, L. H. Staendner, K. N. Timmis, and C. A. Guzman. 1997. Green fluorescent protein-based reporter systems for genetic analysis of bacteria including monocopy applications. Gene 196:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taso, S. G. S., C. F. Brunk, and R. E. Perlman. 1983. Hybridization of nucleic acids directly in agarose gels. Anal. Biochem. 131:365-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umelo-Njaka, E., J. F. Nomellini, W. H. Bingle, L. Glasier, R. T. Irvin, and J. Smit. 2000. Expression and testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine candidate proteins prepared with the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein expression system. Vaccine 19:1406-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Heijne, G. J. 1992. Membrane protein structure prediction, hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. Mol. Biol. 225:487-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker, S. G., D. N. Karunaratne, N. R. Ravenscroft, and J. Smit. 1994. Characterization of mutants of Caulobacter crescentus defective in surface attachment of the paracrystalline surface layer. J. Bacteriol. 176:6312-6323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker, S. G., S. H. Smith, and J. Smit. 1992. Isolation and comparison of the paracrystalline surface layer proteins of freshwater caulobacters. J. Bacteriol. 174:1783-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, L., D. V. Mourich, H. M. Engelking, S. Ristow, J. Arnzen, and J. C. Leong. 1991. Epitope mapping and characterization of the infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus glycoprotein using fusion proteins synthesized in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 65:1611-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]