Abstract

Escherichia coli O55 is an important antigen which is often associated with enteropathogenic E. coli clones. We sequenced the genes responsible for its synthesis and identified genes for O-antigen polymerase, O-antigen flippase, four enzymes involved in GDP-colitose synthesis, and three glycosyltransferases, all by comparison with known genes. Upstream of the normal O-antigen region there is a gne gene, which encodes a UDP-GlcNAc epimerase for converting UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-GalNAc and is essential for O55 antigen synthesis. The O55 gne product has only 20 and 26% identity to the gne genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E. coli O113, respectively. We also found evidence for the O55 gene cluster's having evolved from another gene cluster by gain and loss of genes. Only three of the GDP-colitose pathway genes are in the usual location, the other two being separated, although nearby. It is thought that the E. coli O157:H7 clone evolved from the O55:H7 clone in part by transfer of the O157 gene cluster into an O55 lineage. Comparison of genes flanking the O-antigen gene clusters of the O55:H7 and O157:H7 clones revealed one recombination site within the galF gene and located the other between the hisG and amn genes. Genes outside the recombination sites are 99.6 to 100% identical in the two clones, while most genes thought to have transferred with the O157 gene cluster are 95 to 98% identical.

Escherichia coli is a clonal species, with clones normally identified by their combination of O and H (and sometimes K) antigens. E. coli O55:H7 and O157:H7 are important pathogenic clones causing serious diseases in humans (20, 33). Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis of a large number of E. coli strains has shown that E. coli O157:H7 isolates belong to a distinct group which also contains E. coli O55:H7 (9, 26, 43, 44). The H7 fliC genes of O55:H7 and O157:H7 strains are almost identical but differ from those of strains with other O antigens (29, 41). Thus, it has been proposed that transfer of O157 O-antigen genes into an O55:H7 strain was one of the events resulting in the origin of the O157:H7 enterohemorrhagic E. coli clone (34).

The O antigen contributes major antigenic variability to the cell surface, and on the basis of this antigenic variation, 166 O forms have been recognized in E. coli (not including Shigella strains). The surface O antigen is subject to intense selection by the host immune system, which may account for maintenance of the many different O-antigen forms within species such as E. coli. The genes specific to O-antigen synthesis in E. coli are commonly clustered adjacent to the gnd gene between the colanic acid (CA) and his operons (28).

Lateral transfer of large DNA segments is thought to have played an important role in the evolution of bacterial pathogens. The evidence is usually the presence of genes with atypical GC content and/or the distribution of pathogenicity islands or other gene clusters. We, among others, have undertaken extensive studies on O-antigen genes by sequencing and identifying the O-antigen genes, mostly in Salmonella enterica and E. coli, and found evidence for lateral gene transfer at all levels of O-antigen variation (see Reeves [27] for a review). There is evidence for gene transfer in assembly of O-antigen gene clusters (5, 45) and also for transfer of O-antigen gene clusters between clones of a species involving homologous recombination in adjacent genes (35). Finally there is evidence for interspecies transfer of the entire O-antigen gene cluster from Plesiomonas shigelloides to E. coli (31). Tarr et al. (34) showed by sequence comparison that the O157 gene cluster and adjacent gnd gene of the O157:H7 clone cotransferred into an E. coli O55:H7 organism to generate the O157:H7 clone.

It is thought that E. coli and S. enterica diverged from a common ancestor about 140 million years ago (21, 22). It is noteworthy that only three forms of O antigen are common to both species, and in E. coli all three (O55, O111, and O157) are associated with enteropathogenic (and sometimes enterohemorrhagic) E. coli strains. O55 and O111 are the only two colitose-containing O antigens in E. coli. For E. coli O111 and identical S. enterica O35, the organization and sequences of the gene clusters support their derivation from a gene cluster in the common ancestral species, but data are not available for the other cases.

To better understand the genetics of the O55 antigen and the genetic basis of the shift from O55 to O157 in the evolution of E. coli O157:H7, we sequenced the O55 antigen genes and flanking sequence. The O55 O unit is atypical in that two of five colitose biosynthesis pathway genes are located downstream of the gnd gene and a newly described UDP-GlcNAc epimerase (gne) gene is upstream of galF, suggesting formation by addition of genes adjacent to an ancestral gene cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli O55:H7 (isolate TB182, laboratory number M1685) and O157:H7 (isolate K3557, laboratory number M2136) were kindly provided by Phillip Tarr of the University of Washington School of Medicine and Vicki Bennett-Wood of the Royal Children's Hospital, Parkville, Australia, respectively. E. coli type strains for other O antigens are those described before (39). Plasmid pKD20 was kindly provided by N. Patrick Higgins, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Construction of random DNase I bank for sequencing DNA fragments.

Chromosomal DNA used as the template for PCR was prepared by using Wizard DNA preparation kits from Promega. Long PCR was carried out using the Expand Long Template PCR system from Boehringer, and products were subjected to DNase I digestion and cloned into pGEM-T to make banks for sequencing by the method described previously (39). Products of 12 individual PCRs were pooled to make each bank in order to limit the effect of PCR errors.

Sequencing and analysis.

A total of 27,730 bp of DNA sequence, from the end of the CA gene cluster to hisG, was obtained from the O55:H7 strain (Fig. 1) in three overlapping segments. We sequenced the galF to gnd region and from gnd to the distal end of the his operon regions using random DNase I banks constructed from DNA amplified by long PCR using primer pairs 1523 (5′-ATTGTGGCTGCAGGGATCAAAGAAATC) and 1524 [tag-TC(A,G)CGCTG(A,C,T,G)GCCTG(A,G)AT(C,T)ARGTT(A,C)GC] and 3380 (5′-GATATTGCAAACCTGCTGCTTGCTCCGTATTTC) and 3378 (5′-TATCCTCACCTGCTCAAGCGTTATCTCGACCAG), respectively (bases in parentheses for 1524 indicate redundancy). The region upstream of galF was PCR amplified using primers 3667 (5′-GGATTAATCACCATATTGT) and 3432 (5′-ATAAGAGGTGTCGAAGTG) and sequenced by primer walking.

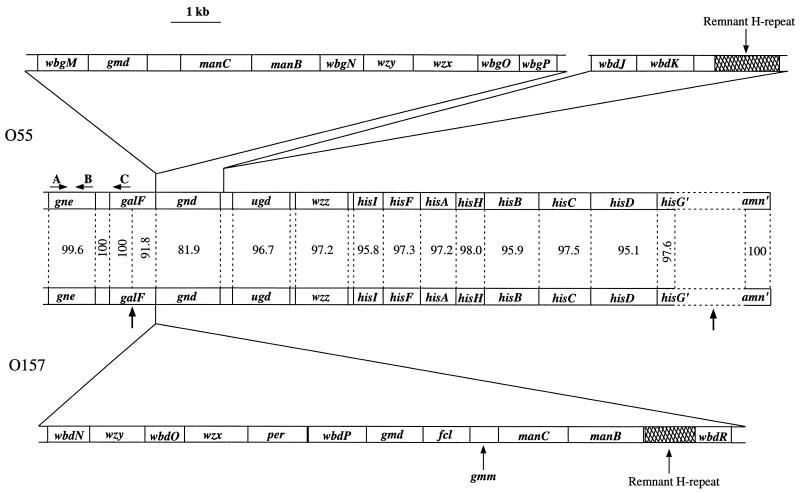

FIG. 1.

Maps of the E. coli O55:H7 and E. coli O157 O-antigen genes (top and bottom) and respective flanking regions, including the gne gene (center). Differences between the DNA sequences are given for each gene in the flanking regions. Proposed recombination sites for transfer of the O157 gene cluster into an O55:H7 strain are indicated by vertical arrows. A, B, and C indicate the binding sites for primers used in PCR of gne (primers at sites A and B for detection of gne were inside the primers for cloning gne).

DNA template for sequencing was prepared using the 96-well format plasmid DNA miniprep kit from Advanced Genetic Technologies Corp and the procedure developed at the Institute for Genomic Research (36). Sequencing was performed with an Applied Biosystems 377 automated DNA sequencer at the Sydney University and the Prince Alfred Macromolecular Analysis Centre. Sequence data were assembled using the Phred/Phrap package of the University of Washington Genome Center, and sequence annotation was done using the program Artemis from the Sanger Centre. We used the algorithm described by Eisenberg et al. (7) to identify potential transmembrane segments from the amino acid sequence.

Cloning of the gne gene.

The gne gene was PCR amplified from strain M1685 using primers 3859 (5′-ATATAGAGCTCATGAACGATAACGTTTTGCTC) and 3860 (5′-CGGGATCCTTACTCAGACAAAAATGCTAT), which bind to the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, of the gne gene (shown as A and B in Fig. 1) and have SacI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively, incorporated at their 5′ ends. The PCR product was cloned into the SacI and BamHI sites of pTRC99A (from Pharmacia) to make plasmid pPR2062. In plasmid pPR2062, the cloned gne gene is under the control of a trc promoter, which is repressed by the LacIq protein encoded by a gene in the same plasmid. We used 2.5 mM IPTG (isopropylthiogalactopyranoside) to induce expression of the cloned gene.

Deletion of gne gene from O55:H7 and O157:H7 strains.

The gne genes of both strains were replaced by a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene using the RED recombination system of phage lambda (6, 46). The CAT gene was PCR amplified from plasmid pKK232-8 (Pharmacia) using primers binding to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene, with each primer carrying 36 bp based on the O55:H7 DNA which flanks gne. The PCR product was transformed into M1685 and M2136 carrying pKD20, and chloramphenicol-resistant transformants were selected after induction of the RED genes according to the protocol described by Datsenko and Wanner (6). PCR using primers specific to the CAT gene and O55:H7 or O157:H7 DNA flanking the gne gene was carried out to confirm the replacement.

Assay for UDP-GlcNAc epimerase.

We used the assay first described by Glaser (12) and recently used by others (4, 8) for UDP-GlcNAc epimerase. UDP-GalNAc is used as the substrate, and after removal of the UDP moiety by acid hydrolysis, the product is measured by the Morgen-Elson reaction (23), in which GlcNAc yields a threefold-higher color reading than GalNAc. Reactions were performed at 37°C for 10 min with a total volume of 0.5 ml (pH 9.0) which contains 10 mM glycine, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM UDP-GalNAc, and 50 μl of cell extract. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 μl of 10 M HCl to bring the pH to 2.0, followed by incubation at 100°C for 20 min for hydrolysis. After neutralization with 1.25 μl of 10 M NaOH, 0.05 ml of freshly prepared 1.5% (vol/vol) acetic anhydride in acetone was added. After 5 min at room temperature, 0.15 ml of a 0.7 M potassium tetraborate solution was added, and the mixture was boiled immediately for 3 min. After cooling, 0.3 ml of DMAB reagent (30) was added without shaking, followed by addition of 2.7 ml of glacial acetic acid. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, the A585 was recorded. The assay was done in duplicate for each sample, and standard curves, prepared by using UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-GalNAc subjected to acid hydrolysis under the same conditions, were used to estimate the concentration of UDP-GlcNAc.

Other methods.

Membrane preparation, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and silver staining of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for visualizing LPS were carried out as described by Wang and Reeves (38). Preparation of cell extracts and total protein determination were carried out as described by Estrela et al. (8).

Gene nomenclature.

We have used gene names based on principles described previously (28). In the case of wbdJ and wbdK, the name is expected to change when the GDP-colitose biosynthesis pathway is better understood and the function order is known. Any such change will be reported on the Bacterial Polysaccharide Genes Database (BPGD) website (http://www.angis.su.oz.au/BacPolGenes/welcome/html).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The O55:H7 amn sequence and the sequence covering wcaM to hisG have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF461121 and AF461122, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequencing.

We sequenced 27,730 bp of DNA of the O55:H7 strain, from the end of the CA gene cluster to hisG, starting with the galF to gnd region and extending it in both directions in a search for recombination sites.

O55 O-antigen genes.

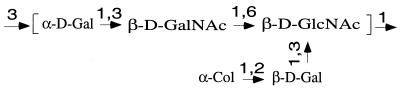

The structure of the O55 O unit is known (Fig. 2), and we expect genes for the synthesis of GDP-colitose, an O-antigen flippase gene (wzx), an O-antigen polymerase gene (wzy), an O-antigen chain length determinant gene (wzz), and transferase genes for two galactose residues, N-acetyl-galactosamine and colitose. Note that O55 antigen synthesis is initiated by transfer of GlcNAc-1-phosphate (GlcNAc-1-P) to undecaprenyl-1-P by WecA , encoded in the enterobacterial common antigen gene cluster (1, 18).

FIG. 2.

Structure of the E. coli O55 antigen (17). Gal, galactose; Col, colitose.

GDP-colitose pathway genes.

We identified previously in the O111 gene cluster the genes thought to be involved in synthesis of GDP-colitose and proposed a biosynthetic pathway (2, 37). The O55 manB, manC, and gmd genes of this pathway were found as expected between galF and gnd (see Table 1 for details of all genes). However, wbdK and wbdJ, for the last two steps of the proposed GDP-colitose pathway, were found downstream of gnd, as also reported by Tarr et al. (34), after we had finished the sequencing work. The presence of the five genes of the proposed pathway in both the O157 and O55 gene clusters provides strong support for their involvement in GDP-colitose synthesis.

TABLE 1.

Summary of O55 antigen genes

| Gene | Location in sequence | No. of amino acids | Similar proteins (accession no.) | % Identity/% similarity (no. of amino acids) | Putative function of O55 protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gne | 204-1199 | 331 | GalE, S. enterica serovar Typhi (GALE_SALTI) | 29/47 (331) | UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase |

| galF | 1442-2335 | 297 | GalF, E. coli K-12 (D90842) | 98/99 (297) | UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase |

| wbgM | 2716-3810 | 364 | WbbP, S. dysenteriae 1 (M96064) | 28/46 (316) | Galactosyltransferase |

| WbnE, E. coli O113 (AF172324) | 40/60 (364) | ||||

| gmd | 3831-4949 | 372 | Gmd, E. coli K-12 (AE000295) | 90/95 (372) | GDP-mannose dehydratase |

| manC | 5588-7045 | 485 | ManC, E. coli O157 (AF061251) | 72/84 (485) | Mannose-1-P guanosyltransferase |

| manB | 6993-8420 | 475 | ManB, E. coli O157 (AB008676) | 85/92 (455) | Phosphomannomutase |

| wbgN | 8417-9289 | 290 | FUT2, human (AAC24453) | 23/47 (290) | Fucosyltransferase |

| wzy | 9301-10278 | 325 | See text | O-antigen polymerase | |

| wzx | 10296-11573 | 425 | See text | O-antigen flippase | |

| wbgO | 11570-12367 | 265 | WbcG, Yersinia enterocolitica O8 (U46859) | 34/55 (212) | Glycosyltransferase |

| wbgP | 12372-13127 | 251 | WbdN, E. coli O157 (AF061251) | 31/56 (160) | Glycosyltransferase |

| gnd | 13211-14617 | 468 | Gnd, E. coli strain ECOR4 (M64324) | 94/97 (468) | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase |

| wbdJ | 14729-15652 | 307 | WbdJ, E. coli O111 (AAC44884) | 67/82 (307) | GDP-colitose biosynthesis pathway gene |

| wbdK | 15649-16815 | 388 | WbdK, E. coli O111 (AAC44885) | 80/89 (388) | GDP-colitose biosynthesis pathway gene |

| ugd | 18730-19896 | 388 | Ugd, E. coli O157:H7 (AB008676) | 99/99 (388) | UDP-glucose-6-dehydrogenase |

| wzz | 19986-21023 | 345 | Wzz, E. coli O157:H7 (AE000294) | 98/98 (331) | O-antigen chain length determinant |

Transferase genes.

WbgM is 27% identical to WbbP (13) of Shigella dysenteriae 1 and has a similar hydrophobic profile. WbbP is a galactosyltransferase forming an α(1-3) linkage to GlcNAc (13), and we suggest that WbgM is the transferase for the α(1-3) galactosyl linkage to GalNAc. WbgN shows 23% identity (47% similarity) with the FUT2 protein, a human secretor blood group fucosyltransferase forming an α(1-2) linkage to β-galactose (15). WbgN may well form the α-colitose-(1-2)-β-galactose linkage. WbgO and WbgP show similarity with many other putative bacterial polysaccharide transferases, and they are likely to be the remaining two transferases.

O-antigen processing genes.

The wzz gene was easily identified, as it is 98% identical to that of E. coli K-12 (GenBank entry AE000294) and is in the usual location between gnd and hisI. A presumptive wzx gene was identified as encoding an integral inner membrane protein with 12 predicted transmembrane segments and confirmed by a motif search using the method described by Jiang et al. (14). The gene we consider to be wzy encodes a protein with 10 predicted transmembrane segments and one loop of 52 amino acid residues, a characteristic topology for O-antigen polymerases (19). No motifs were shared by this protein and other known Wzy proteins. However, given that this gene, wzx, and wzy are the only genes with inferred products having multiple predicted transmembrane segments and that it has the expected topology, we conclude that it is the wzy gene.

The gne gene.

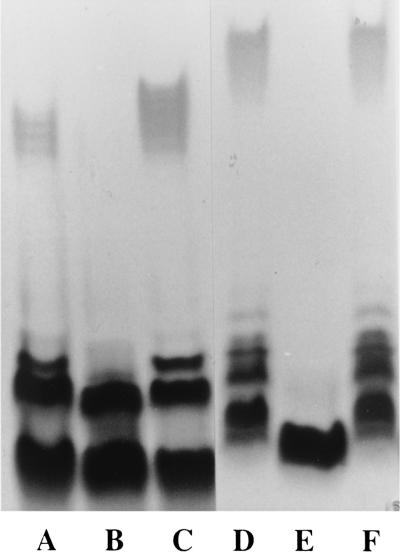

In E. coli K-12 and S. enterica LT2, wcaL, the last gene of the colanic acid gene cluster, is separated by one gene of unknown function from galF (32). In the O55:H7 strain, there is an additional gene upstream of galF, also found in O157:H7, that shows 48% identity to an Edwardsiella ictaluri gene of unknown function (GenBank AAL25633) and 22% or lower identity with a range of putative or characterized UDP-galactose 4-epimerase genes. We suspected that this gene might encode a UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase, responsible for conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-GalNAc, as GalNAc is present in both the O55 and O157 antigens. Deletion of the gene from either an O55 or O157 strain (to make strains M2313 and M2311, respectively) led to loss of O-antigen production, which was restored when plasmid pPR2062 was present (Fig. 3). We also showed that strain M2313 was devoid of UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase activity, while the parent strain (M1685) and M2313 carrying plasmid pPR2062 (M2318) both had the function (Table 2). E. coli K-12 strain P4971 was negative for the epimerase activity but positive after transfer of plasmid pPR2062 (data not shown). The gene upstream of galF is clearly a UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase gene essential for synthesis of O55 and O157 O antigens, and it was named gne.

FIG. 3.

Requirement of the gne gene for expression of the E. coli O55 and O157 antigens. Membrane extracts were run on SDS-PAGE gels and stained by silver staining. Lanes: A, M1685 (wild-type O55:H7); B, M2313 (M1685 missing the gne gene); C, M2313 carrying plasmid pPR2062; D, M2136 (wild-type O157:H7); E, M2311 (M2136 missing the gne gene); and F, M2311 carrying plasmid pPR2062.

TABLE 2.

UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase activity in cell extracts of E. coli strains

| Strain | GlcNAca (μM) | Sp actb [U (mg of protein)−1] | % of wild-type activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1685 | 1.822 | 0.0048 | 100 |

| M2313 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M2318 | 2.151 | 0.0057 | 118 |

Concentration of UDP-GlcNAc after the reaction.

One unit of enzyme is defined as the amount which catalyzes the formation of 1 μmol of UDP-GlcNAc in 1 min under the conditions of our assay.

gne genes have been identified in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa O6 (4) and E. coli O113 (24) gene clusters. The P. aeruginosa gene, identified by biochemical activity, is homologous throughout its length to the O55 gene, but the encoded proteins have only 20% amino acid identity. The E. coli O113 gene was previously believed to be a galE gene, but the evidence for its being a UDP-GlcNAc epimerase gene was convincing, although indirect (25). The O113 Gne protein is 26.7 and 18.6% identical to the Gne proteins of O55 and P. aeruginosa O6, respectively. This is the first time that we have believed it was not sufficient to use sequence similarity for assignment of function for nucleotide sugar pathway genes.

In summary, four putative transferase genes, five GDP-colitose synthesis genes, a gne gene, an O-antigen polymerase gene, a flippase gene, and a chain length determinant gene were identified. They account for all the genes needed for the synthesis and processing of the O55 O unit. In addition, an H repeat and remnant gmm gene were found, as discussed below.

gne gene of E. coli O55 and O157 is present in many other E. coli strains.

There are 62 E. coli O-antigen forms with reported structures, of which 22 include GalNAc. We carried out PCR on the type strains for the 62 O antigens using primers based on the E. coli O55 and O157 gne genes (5′-ACAGATTGGTGATGTTCG and 5′-ATCAAAGCAATATCCACC, indicated in Fig. 1 by arrows A and B). Fourteen of the 22 strains with GalNAc-containing structures gave a positive result, whereas only 4 of the other 40 strains were positive. PCR with one primer in gne and the other in galF (indicated by C in Fig. 1) gave a positive result for 12 of the 14 previously positive strains and for two additional strains with GalNAc-containing structures. The 16 strains positive in one or both experiments must have the gne gene found in the O55 and O157 strains, and of these 14 were confirmed to be at the same site upstream of galF. PCR with the same 22 strains and primers appropriate to the O113 gne gene previously described by Paton et al. (25) revealed no additional strains carrying this gene. It seems that the form of the gne gene found in O55 and O157 is the most common in E. coli.

The presence of gne in some strains with O antigens reported to lack GalNAc is not surprising, as a strain carrying a gne gene as part of its required O-antigen gene set would retain the gene if its O antigen were replaced by homologous recombination involving recombination within galF, even if the incoming O antigen lacked GalNAc.

Origins of the O55 gene cluster.

The O55 gene cluster is atypical in that while most of its O-antigen genes are in the usual O-antigen gene cluster site between galF and gnd, two of the GDP-colitose pathway genes (wbdJ and wbdK) and the gne gene are outside of, although close to, this region.

In the E. coli O111 gene cluster, the GDP-colitose pathway genes are contiguous in the order gmd, gmm, manC, manB, wbdJ, and wbdK. Gmm, a GDP-mannose mannosyl hydrolase (11), would remove GDP-mannose from the pathway and has no obvious role. However, gmm is treated as part of the GDP-sugar pathway, as it has been found only in association with GDP-fucose, GDP-colitose, or GDP-perosamine pathway genes (37, 39, 40).

The O55 gene cluster has a 620-bp remnant gmm gene between gmd and manC (57% identity to the O157 gene at the amino acid level). The presence of only part of gmm indicates a deletion in the O55 gene cluster. The simplest hypothesis is that an ancestral gene cluster included a pathway for a GDP-sugar derived from 4-keto-6-deoxy-GDP-mannose. One can envisage such an ancestral gene cluster's gaining the ability to synthesize GDP-colitose by incorporation of genes wbdJ and wbdK by lateral transfer. If colitose were incorporated into the O antigen, the change in O antigen could have been beneficial in specific circumstances and selected.

It would not be necessary for the additional genes to be close to the main gene cluster for synthesis of colitose. However, Lawrence and Roth (16) have pointed out that close proximity of genes is important if a biosynthetic pathway is to be readily transferred by homologous recombination and proposed that selection for transferability may drive operon formation and maintenance. O-antigen gene clusters are subject to high levels of lateral transfer within E. coli and S. enterica, and the situation observed for O55 represents what one would expect as an intermediate in gene cluster assembly. The current locations of wbdJ and wbdK, probably mediated by the H repeat, as proposed by Tarr et al. (34), would suffice to enable cotransfer with the other O55 genes.

GDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-mannose, the product of Gmd action, is a branch point for synthesis of GDP-fucose, GDP-perosamine, GDP-colitose, and GDP-d-rhamnose. The post-gmd part of the original GMD-sugar pathway has been lost, presumably in the same event that deleted part of gmm and presumably also after gain of the two genes that complete the GDP-colitose pathway. The deletion event also could be driven by selection, as colitose and the original sugar would confer different antigenic specificities on the O antigen and the presence of two specificities may be undesirable. The sequence of events is speculative, but such processes are the most likely means by which the remarkable diversity of the O antigens was generated, and the O55 gene cluster has the hallmarks of an intermediate form, with all genes assembled in close proximity but not yet fully integrated. The O55 antigen is identical to the O50 antigen of S. enterica, and it is possible that assembly occurred in the common ancestor of the two species, as postulated (40) for the E. coli O111 and S. enterica O35 antigens, but this can only be assessed by sequencing the S. enterica O50 gene cluster.

wbgN is thought to be the colitose transferase because of its similarity to a transferase for the related sugar fucose. It is between manB and wzy, which are probably part of the ancestral gene cluster, so wbgN most likely evolved as the transferase using the original GDP-sugar as the substrate, but had sufficient cross specificity to function with GDP-colitose.

The gne gene is also an essential part of the O55 gene cluster, but located upstream of the traditional O-antigen locus between galF and gnd. The portion of the chromosome that transfers O55 synthesis between lineages is presumably the gne to wbdJ segment, although, as we saw for O157 of the O157:H7 clone, this can be reduced if the recipient includes a gne gene. However, we do not see it as useful to give a specific name to such an extended group of genes, as proposed by Tarr et al. (34).

Transfer of O157 gene cluster to an O55:H7 strain to generate the O157:H7 clone.

It is proposed that the O157:H7 clone was derived from the O55:H7 clone by replacement of the O-antigen genes (10, 34). We sequenced DNA flanking the O-antigen genes to seek confirmation of this proposal. A convincing recombination site was found within the galF gene, but the other is more distant, between hisG and amn (about 35 kb apart in E. coli K-12 [3]). Genes located outside of the two recombination points are almost identical in the two clones (Fig. 1), gne, amn, and half of galF fitting the expectation for housekeeping genes in clones that are nearly identical by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. The housekeeping genes between the two points are mostly from 95.1 to 98% identical in the two clones, showing a much higher level of sequence difference. Our data thus provide some detail of the recombination event proposed for the origin of the O157:H7 clone. The difference for the his, wzz, and ugd genes represents the level of divergence between the O157 donor strain and the O55:H7 clone and is within the range expected for unrelated E. coli clones (42).

The divergence for the gnd gene and the 3′ half of the galF gene is higher than found for other housekeeping genes within the transferred segment (Fig. 1). The gnd gene is known to be more variable than housekeeping genes in general and this is thought to be due to proximity to the O-antigen gene cluster and maintenance of a large number of O-antigen forms (35). The galF gene is also highly variable (R. Lan, D. M. Ryan, P. BouAntoun, and P. R. Reeves, unpublished data), and the same arguments apply.

It should be noted that the genes common to the O55 and O157 gene clusters, manB, manC, gmd, wzx, wzy, and part of gmm, have substantially divergent sequences and were clearly not involved in the recent recombination event.

General conclusions.

The O55 gene cluster is particularly interesting in that its origin by addition to and loss of genes from an earlier gene cluster is quite clear. The changes to give the GDP-colitose pathway presumably occurred under selection for replacement of the original O antigen by the then-novel O55 antigen. For this to occur, there is no necessity for the additional genes to be located near the other O-antigen genes, and this is most unlikely to have been the case when the two groups of genes first occurred within one cell. In addition to wbdJ and wbdK for GDP-colitose synthesis, the gne gene for UDP-GalNAc synthesis is also outside of the main gene cluster, but again very close to it. In O55 we see what appears to be an intermediate stage in bringing all the genes into a single cluster, presumably a result of selection for intraspecies transfer of the O55 antigen gene cluster

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Australian Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, D. C., and M. A. Valvano. 1994. Role of the rfe gene in the biosynthesis of the Escherichia coli O7-specific lipopolysaccharide and other O-specific polysaccharides containing N-acetylglucosamine. J. Bacteriol. 176:7079-7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastin, D. A., and P. R. Reeves. 1995. Sequence and analysis of the O-antigen gene (rfb) cluster of Escherichia coli O111. Gene 164:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner, F. R., G. I. Plunkett, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, M. W. Davis, K. H. A., M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shau. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creuzenet, C., M. Belanger, W. W. Wakarchuk, and J. S. Lam. 2000. Expression, purification, and biochemical characterization of WbpP, a new UDP-GlcNAc C4 epimerase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O6. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19060-19067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curd, H., D. Liu, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Relationships among the O-antigen gene clusters of Salmonella enterica groups B, D1, D2, and D3. J. Bacteriol. 180:1002-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg, D., E. Schwarz, M. Komaromy, and R. Wall. 1984. Analysis of membrane and surface protein sequences with the hydrophobic moment plot. J. Mol. Biol. 179:125-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estrela, A. I., H. M. Pooley, H. de Lencastre, and D. Karamata. 1991. Genetic and biochemical characterization of Bacillus subtilis 168 mutants specifically blocked in the synthesis of the teichoic acid poly(3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-N-acetylgalactosamine 1-phosphate): gneA, a new locus, is associated with UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase activity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:943-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng, P. 1993. Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by DNA probe specific for an allele of uidA gene. Mol. Cell. Probes 7:151-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng, P., K. A. Lampel, H. Karch, and T. S. Whittam. 1998. Genotypic and phenotypic changes in the emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1750-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frick, D. N., B. D. Townsend, and M. J. Bessman. 1995. A novel GDP-mannose mannosyl hydrolase shares homology with the MutT family of enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:24086-24091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser, L. 1959. The biosynthesis of N-acetylgalactosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 234:2801-2805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gohmann, S., P. A. Manning, C. A. Alpert, M. J. Walker, and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biosynthesis in Shigella dysenteriae serotype1: analysis of the plasmid-carried rfp determinant. Microb. Pathog. 16:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, S.-M., L. Wang, and P. R. Reeves. 2001. Molecular characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 4, 6B, 8, and 18C capsular polysacharide gene clusters. Infect. Immun. 69:1244-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly, R. J., S. Rouquier, D. Giorgi, G. G. Lennon, and J. B. Lowe. 1995. Sequence and expression of a candidate for the human secretor blood group α(1,2)fucosyltransferase gene (FUT2). Homozygosity for an enzyme-inactivating nonsense mutation commonly correlates with the nonsecretor phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 270:4640-4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence, J. G., and J. R. Roth. 1996. Selfish operons: horizontal transfer may drive the evolution of gene clusters. Genetics 143:1843-1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindberg, B., F. Lindh, J. Longren, A. A. Lindberg, and S. B. Svenson. 1981. Structural studies of the O-specific side-chain of the lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli O55. Carbohydr. Res. 97:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier, U., and H. Mayer. 1985. Genetic location of genes encoding enterobacterial common antigen. J. Bacteriol. 163:756-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morona, R., M. Mavris, A. Fallarino, and P. A. Manning. 1994. Characterization of the rfc region of Shigella flexneri. J. Bacteriol. 176:733-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochman, H., and A. C. Wilson. 1987. Evolution in bacteria: evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 26:74-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ochman, H., and A. C. Wilson. 1987. Evolutionary history of enteric bacteria, p. 1649-1654. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, vol. II. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oguchi, M., and M. Oguchi. 1979. Tetraborate concentration on Morgen-Elson reaction and an improved method for hexosamine determination. Anal. Biochem. 98:433-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paton, A. W., and J. C. Paton. 1999. Molecular characterization of the locus encoding biosynthesis of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen of Escherichia coli serotype O113. Infect. Immun. 67:5930-5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paton, A. W., J. C. Paton, and R. Morona. 2001. Neutralization of Shiga Stx1, Stx2c, and Stx2e by recombinant bacteria expressing mimics of globotriose and globotetraose. Infect. Immun. 69:1967-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pupo, G. M., D. K. R. Karaolis, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1997. Evolutionary relationships among pathogenic and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strains inferred from multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and mdh sequence studies. Infect. Immun. 65:2685-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves, P. R. 1993. Evolution of Salmonella O-antigen variation by interspecific gene transfer on a large scale. Trends Genet. 9:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves, P. R., M. Hobbs, M. Valvano, M. Skurnik, C. Whitfield, D. Coplin, N. Kido, J. Klena, D. Maskell, C. Raetz, and P. Rick. 1996. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 4:495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid, S. D., R. K. Selander, and T. S. Whittam. 1999. Sequence diversity of flagellin (fliC) alleles in pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:153-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reissig, J. L., J. L. Strominger, and L. F. Leloir. 1955. A modified colorimetric method for the estimation of N-acetylaminosugars. J. Biol. Chem. 217:959-966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shepherd, J. G., L. Wang, and P. R. Reeves. 2000. Comparison of O-antigen gene clusters of Escherichia coli (Shigella) Sonnei and Plesiomonas shigelloides O17: Sonnei gained its current plasmid-borne O-antigen genes from P. shigelloides in a recent event. Infect. Immun. 68:6056-6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevenson, G., K. Andrianopoulos, H. Hobbs, and P. R. Reeves. 1996. Organization of the Escherichia coli K-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid. J. Bacteriol. 178:4885-4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarr, P. I. 1995. Escherichia coli O157:H7: clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiological aspects of human infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarr, P. I., L. M. Schoening, Y. L. Yea, T. R. Ward, S. Jelacic, and T. S. Whittam. 2000. Acquisition of the rfb-gnd cluster in evolution of Escherichia coli O55 and O157. J. Bacteriol. 182:6183-6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thampapillai, G., R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1994. Molecular evolution in the gnd locus of Salmonella enterica. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11:813-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Utterback, T. R., L. A. McDonald, and R. A. Fuldner. 1995. A Reliable, efficient protocol for 96-well plasmid DNA miniprep with rapid DNA quantification for high-throughput automated DNA sequencing. Genome Sci. Technol. 1:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, L., H. Curd, W. Qu, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Sequencing of Escherichia coli O111 O-antigen gene cluster and identification of O111-specific genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3182-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, L., and P. R. Reeves. 1994. Involvement of the galactosyl-1-phosphate transferase encoded by the Salmonella enterica rfbP gene in O-antigen subunit processing. J. Bacteriol. 176:4348-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, L., and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Organization of Escherichia coli O157 O-antigen gene cluster and identification of its specific genes. Infect. Immun. 66:3545-3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, L., and P. R. Reeves. 2000. The Escherichia coli O111 and Salmonella enterica O35 gene clusters: gene clusters encoding the same colitose-containing O-antigen are highly conserved. J. Bacteriol. 182:5256-5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, L., D. Rothemund, H. Curd, and P. R. Reeves. 2000. Sequence diversity of the Escherichia coli H7 fliC genes: implication for a DNA based typing scheme for E. coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1786-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whittam, T. S. 1996. Genetic variation and evolutionary processes in natural populations of Escherichia coli, p. 2708-2720. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 2. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whittam, T. S., and R. A. Wilson. 1988. Genetic relationships among pathogenic Escherichia coli of serogroup O157. Infect. Immun. 56:2467-2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whittam, T. S., M. L. Wolfe, I. K. Wachsmuth, F. Ørskov, I. Ørskov, and R. A. Wilson. 1993. Clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis and infantile diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 61:1619-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiang, S. H., M. Hobbs, and P. R. Reeves. 1994. Molecular analysis of the rfb gene cluster of a group D2 Salmonella enterica strain: evidence for its origin from an insertion sequence-mediated recombination event between group E and D1 strains. J. Bacteriol. 176:4357-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, E. C. Lee, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and D. L. Court. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]