Abstract

Immunosuppression with SRL may provide an opportunity to avoid long-term exposure to the nephrotoxicity of CNI. Thus, we have initiated an experimental protocol of IL-2r antibody induction , prednisone, MMF and SRL in pediatric renal transplant recipients (median age 15.5 yr, IQR 8.5, range 1.3–21.7). The recipients were treated with daclizumab every2 wk for the first 2 months, prednisone on a tapering schedule, MMF at 1200 mg/m2/dayand SRL given b.i.d. The SRL was dosed to achieve defined target whole blood 12-h trough levels. We performed 24 SRL PK profiles in 13 stable pediatric renal transplant recipients at 1 and 3 months post-transplant. Half-life (T1/2) and terminal T1/2 were 9.7 (7.1–24.6) and 10.8 (4.4–95.2) hours (median, range) respectively at month 1, and were 9.6 (5–17.8) and 12.1 (4.7–71.0) hours respectively at month 3. SRL trough levels correlated with AUC (r2 = 0.84, p < 0.001). There was no relationship between SRL and 2 mycophenolic acid (MPA) AUC values (r2 = 0.04). During the first 3 months post-transplant only one patient experienced severe neutropenia and another patient had subclinical (histologic) evidence of a mild acute rejection episode with no change in renal function. We conclude that the T1/2 of SRL in pediatric renal transplant recipients not treated with CNI is much shorter than what has been reported for adults, due to rapid metabolism. We conclude that children require SRL dosing every12 h, higher doses and frequent drug monitoring to achieve target SRL concentrations.

Keywords: sirolimus, pharmacokinetics, children, kidney transplantation, half-life, mycophenolate mofetil

Abbreviations: CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PK, pharmacokinetics; SRL, sirolimus; ; T1/2, half-life

SRL is an mTOR inhibitor that provides several advantages over CNI immunosuppressive protocols. mTOR inhibitors such as SRL have been shown to result in less renal and gastrointestinal toxicity, and beneficial effects on countering vascular proliferation in comparison with 4 CNI such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Complications of SRL include hyperlipidemia that often requires co-therapy with lipid-lowering agents, and transient thrombocytopenia.

Current SRL use in children is based mostly on extrapolation of PK data in adult transplant recipients and single dose PK data in children on hemodialysis. One study of adult transplant recipients showed that the SRL T1/2 is 62 ± 16 h (1). Another study of single dose SRL in 16 stable, adult renal transplant recipients showed that the elimination T1/2 ranged from 43.8 to 86.5 h, with a mean of 56.9 h (2). A single dose PK study in uremic children on hemodialysis showed similar T1/2 values (70.5 ± 40 h in children and 55.3 ± 18 h in adolescents) (3). However, these data do not reflect steady state SRL PK in stable, pediatric renal transplant recipients.

Previously, young children were reported to have poor short and long-term graft survival. Proposed reasons for this poor survival included an hypothesized heightened immune response, especially in infants (4, 5). However, other causes were likely more important. Children are known to have higher rates of drug metabolism, particularly with respect to key cytochrome enzymes compared with adults (6–12). Faster drug metabolism is very likely the reason why cyclosporine T1/2 is notoriously shorter in children compared with adults. One study determined that cyclosporine T1/2 was 9.3 h in children, compared with 16–27 h in adults (13).

Therefore, it is possible that lack of pediatric-specific PK information previously led to insufficient provision of these drugs to children. Thus, suboptimal immunosuppression, rather than an inherent immune hyper-responsiveness, may have been the cause of higher rejection rates previously seen in young children. Improved age-specific dosing, therefore, may have been instrumental in the recently observed improved outcomes in children (14, 15).

We have initiated an experimental protocol of IL-2r antibody induction, prednisone, MMF and SRL in pediatric renal transplant recipients, including SRL PK studies at 1 and 3 months after transplantation. The goal of this study is to assess SRL PK in children on a CNI-free protocol, and to determine whether these pediatric renal transplant recipients require different doses or dosing schedules of SRL.

Patients and methods

All PK profiles were performed as part of an ongoing uncontrolled pilot trial of CNI-free immunosuppression. The experimental protocol consisted of IL-2r antibody induction given at transplant and every2 wk for 2 months; SRL (b.i.d.) dosed to target 12-h trough levels of 25 ng/mL for months 0–2, 20 ng/mL for months 3–6, and 15 ng/mL beyond 6 months; MMF 1200 mg/m2/daydivided b.i.d.; and prednisone on a tapering schedule. Twenty-four SRL PK profiles were performed in 13 stable pediatric and adolescent renal transplant recipients. SRL PK profiles were performed at month 1 in all 13 patients, and at month 3 in 11 of 13 patients. Six profiles were performed in four children under the age of 6 yr. Six of the 13 patients were female. Patients’ ages ranged from 3.1 to 21.7 yr with a median age of 15.5 yr. At month 1, eight of 13 patients were receiving the liquid SRL formulation, and at month 3, four of 11 patients were receiving the liquid SRL formulation.

PK samples were obtained at 0, 1, 2, 3, 8, and 12 h after dosage administration. Whole blood liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry was performed for SRL, and whole blood HPLC with UV detection was performed for MMF MPA levels. The trapezoid method was utilized to calculate 12-h AUC. Each patient’s initial T1/2 was calculated as the T1/2 demonstrated immediately after rapid-phase redistribution. In addition, each patient’s terminal T1/2 was calculated as the T1/2 demonstrated by the last two time points. Lipid profiling was performed at months 1 and 3, including total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides. Lipid-lowering therapy was initiated in patients with fasting cholesterol consistently>200 mg/dL.

Two patients were withdrawn from the study prior to obtaining month-3 profiles. One patient was withdrawn from the study at month 3 due to concerns regarding a mild cellular infiltrate observed in a surveillance biopsy, albeit in the absence of overt clinical rejection at that time or subsequently. Another patient was withdrawn at month 3 due to refractory neutropenia despite discontinuation of MMF. No other patients developed acute rejection or significant hematologic abnormalities (i.e. requiring a change in therapeutic regimen). One patient was switched from MMF to azathioprine due to gastrointestinal symptoms during the first post-transplant month.

Values are expressed as median and range, and displayed in boxplot format. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between groups. Simple linear regression was used to assess the correlation of SRL trough levels vs. 12-h SRL AUC, SRL AUC vs. MPA AUC, and subject age vs. SRL T1/2. The R software package was utilized for data analysis and figure generation (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

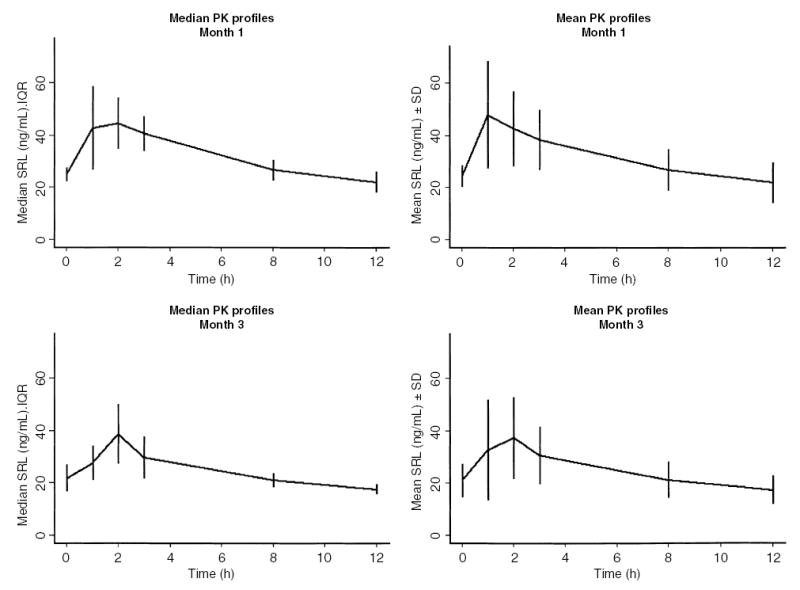

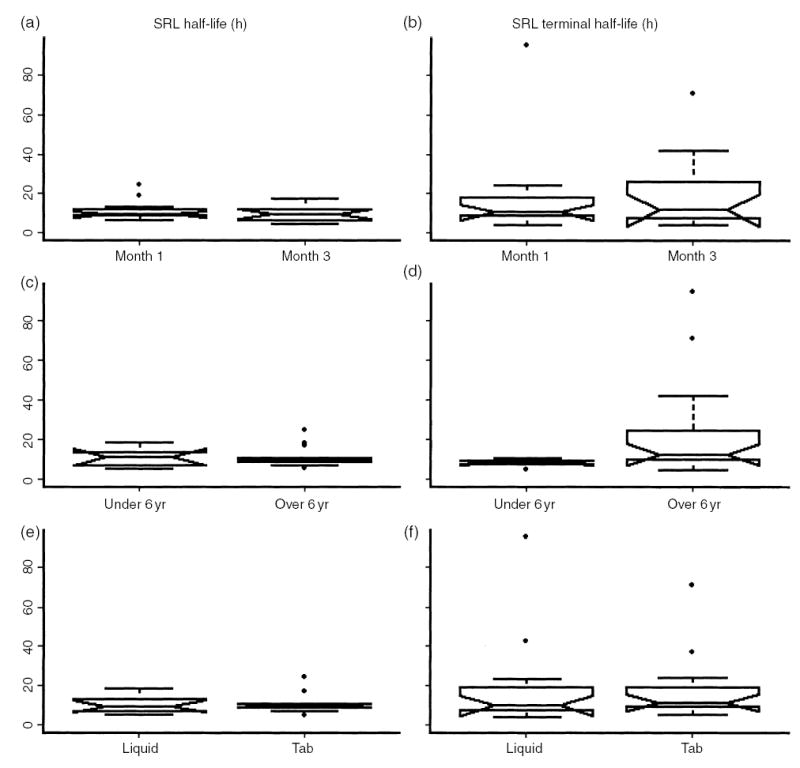

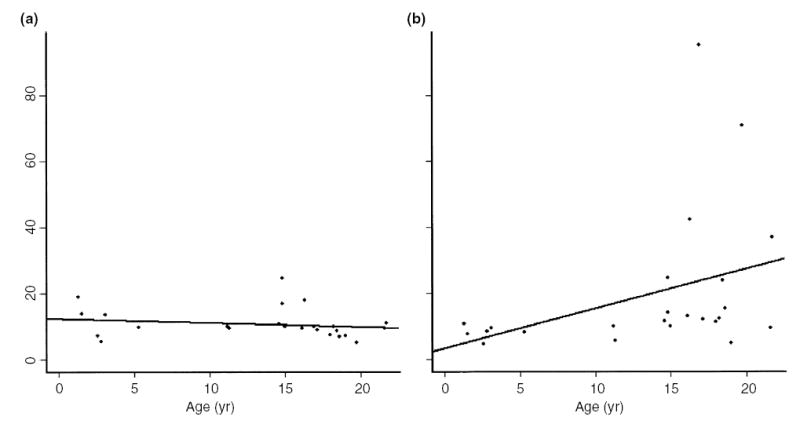

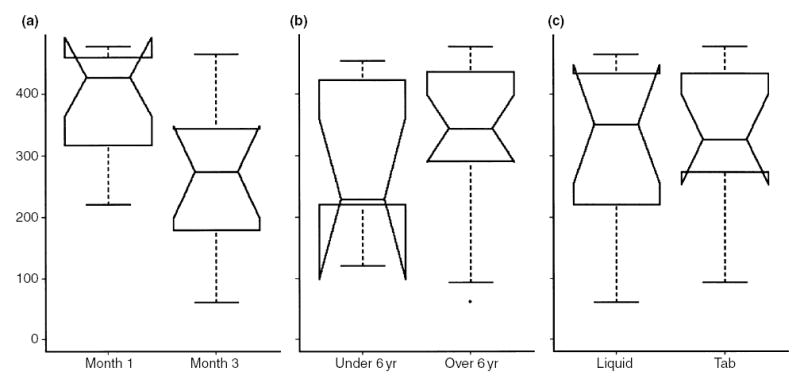

A total of 24 SRL PK profiles were completed. SRL PK profiles at months 1 and 3 are shown in Fig. 1. The median SRL doses were 15.0 mg/m2/day (range 4.2–26.1) at month 1, and 9.0 mg/m2/day (range 3.3–16.0) at month 3. Twelve of the 13 patients were receiving MMF at months 1 and 3. The median MMF doses were 1154.7 mg/m2/day (range 838.1–1307.2) at month 1, and 1117.3 mg/m2/day (range 816.4–1333.3) at month 3. The maximum concentration (Cmax) was 47.4 (12–81) and 36.4 (12–79.3) ng/mL at 1 and 3 months, respectively (median, range). The median time of maximum concentration (Tmax) was 1 (1–8) and 2 (0–8) hours at 1 and 3 months, respectively. Half-life (T1/2) and terminal T1/2 were 9.7 (7.1–24.6) and 10.8 (4.4–95.2) hours, respectively, at month 1, and were 9.6 (5–17.8) and 12.1 (4.7–71.0) hours, respectively, at month 3 (Fig. 2, top row). When stratified by age (6 yr, n = 6 PK profiles in four patients vs. >6 yr, n = 18 PK profiles in nine patients), T1/2 was not significantly different between the two age groups (11.5 h, range 5.2–18.8 h ≤ 6 yr vs. 9.6 h, range 5–24.6 h, >6 yr). However, terminal T1/2 was significantly shorter in the younger group (8.2 h, range 4.4– 10.6 h ≤ 6 yr, vs. 12.6 h, range 4.7–95.2 h >6 yr, p < 0.05; Fig. 2, middle row). There was no significant correlation between subject age and T1/2 (r2 = 0.03, p = 0.4; Fig. 3, left side). However, there was a correlation between subject age and terminal T1/2 that approached statistical significance (r2 = 0.14, p = 0.07; Fig. 3, right side). Neither T1/2 nor terminal T1/2 were significantly different between subjects receiving the liquid or tablet form of SRL (Fig. 2, bottom row).

Fig. 1.

Median (IQR) and mean (s.d.) SRL PK profiles at month 1 and month 3 following renal transplantation in pediatric renal transplant recipients.

Fig. 2.

Half-life (T1/2) and terminal T1/2 stratified by month 1 and month 3 following renal transplantation (a), (b); subject age under or over 6 yr (c), (d); and SRL liquid vs. tablet formulation (e), (f). SRL terminal T1/2 is statistically significantly lower in the younger age group (p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of subject age with SRL T1/2 [(a), r2 = 0.03, p = 0.4] and SRL terminal T1/2 [(b), r2 = 0.14, p = 0.07].

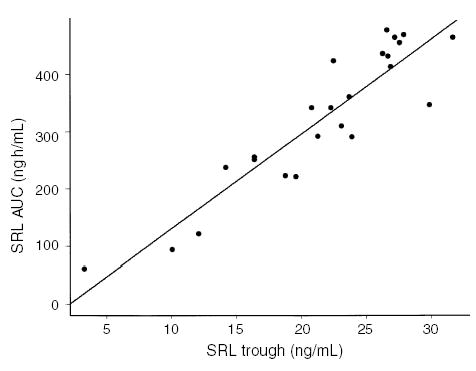

SRL trough levels correlated with AUC (r2 = 0.84, p < 0.001; Fig. 4). SRL AUC was significantly higher at month 1 vs. month 3, corresponding to the higher dosing targets during the first 2 months. SRL AUC levels were not different between the two age groups or between liquid and tablet formulation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of SRL trough levels with AUC (r2 = 0.84, p < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

SRL AUC (ng h/mL) stratified by month 1 and month 3 following renal transplantation (a), subject age under or over 6 yr (b), and SRL liquid vs. tablet formulation (c). SRL AUC is significantly higher at month 1 vs. month 3, corresponding to protocol dosing targets.

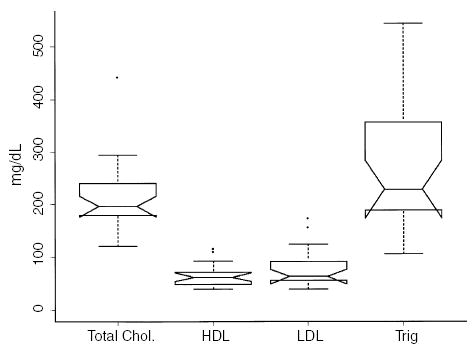

At 1 month, eight of 13 patients (61%) were receiving atorvastatin therapy and eight of 11 (73%) were receiving atorvastatin at 3 months. Lipid profiles are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Lipid profiles in 13 pediatric and adolescent renal transplant recipients.

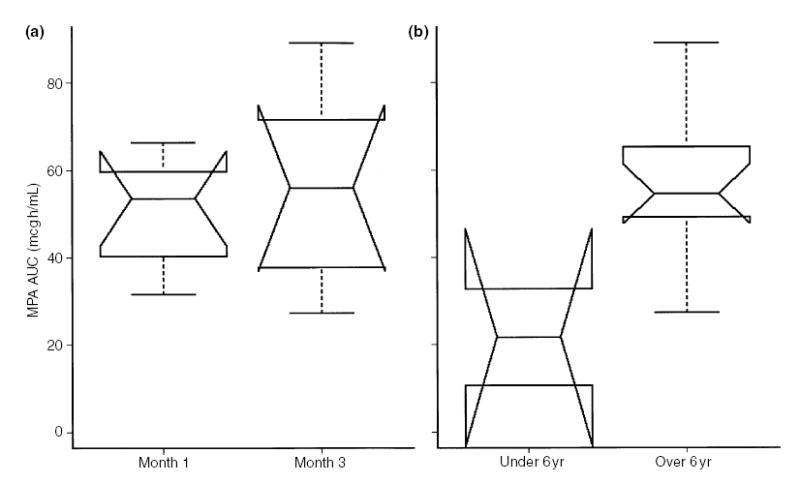

MPA AUC values were not significantly different at month 1 vs. month 3 (month 1: 53.6 mcg h/mL, range 10.6–66.5; month 3: 56.1 mcg h/mL, range 27.3–89.2). MPA AUC values were significantly lower in the younger age group (6 yr and under: 21.75 mcg h/mL, range 10.6–32.9; over 6 yr: 54.75 mcg h/mL, range 27.3–89.2, p < 0.05; Fig. 7). Linear regression analysis of SRL AUC vs. MPA AUC revealed no significant correlation between these two measures (r2 = 0.04, p = 0.44).

Fig. 7.

MPA AUC (mcg h/mL) stratified by month 1 and month 3 following renal transplantation (a) and by subject age under or over 6 yr (b).

Discussion

We have shown that the SRL T1/2 in stable pediatric and adolescent renal transplant recipients on a CNI-free protocol is much shorter than previously thought. Our data show T1/2 in the range of 10–24 h vs. prior reports in the range of 49–70 h. In addition, terminal T1/2 is significantly shorter in patients 6 yr of age and under, compared with adolescents. We attribute this difference to increased rates of drug metabolism in children. Based on these data, we propose that children and adolescents on a CNI-free, SRL-based protocol receive SRL b.i.d. We acknowledge the limitations of determining T1/2 for an orally administered medication and of determining terminal T1/2 from only two data points. However, the T1/2 of SRL quote for adults is based on studies of orally administered medication, and our sampling protocol must take into account the smaller blood volume of pediatric patients (and therefore limits the number of time points sampled). We also acknowledge that the adult PK data cited (1) are from a study population that differs from our study population in several respects other than age, but the goal of this report is to observe the T1/2 of SRL in pediatric patients on a CNI-free protocol.

We found no overt acute rejection episodes during the first three post-transplant months. Although one patient developed refractory neutropenia, no patients developed significant thrombocytopenia. However, up to three to four of our patients required lipid-lowering therapy within the first three post-transplant months, in keeping with the known effect of SRL on blood lipid concentrations.

Our data show a statistically significant difference in SRL terminal T1/2 between children under 6 yr of age and older children on a q12h SRL dosing schedule. We have also shown that there is a correlation between subject age and terminal T1/2 that approaches statistical significance in our small sample size. Although MPA AUC levels were significantly lower in the younger group, we did not find any meaningful correlation between MPA AUC and SRL AUC, suggesting that a robust PK interaction between MMF and SRL is unlikely.

Although we cannot comment on SRL PK in protocols that include CNI, it appears that SRL T1/2 in CNI-inclusive protocols is likely virtually identical to our findings, based on studies performed in 85 pediatric recipients of various allografts (liver, liver-intestine, intestine, lung and bone marrow) who received SRL and tacrolimus. SRL T1/2 in that study was in the range of 14–18 h (16).

Our findings have important implications for the management of pediatric renal transplant recipients. SRL must now join the list of therapies for which children receiving a CNI-free protocol clearly demonstrate PK parameters that are different from adults, to the extent that dose and frequency of administration must be altered. Attributing acute rejection episodes to ‘heightened immune responsiveness’ in children is no longer acceptable, and only serves to mask suboptimal therapeutic regimens. Our findings underlie the importance of performing PK studies in appropriate pediatric target populations each time a new therapeutic agent is released and is likely to be used ‘off-label’ for pediatric patients.

We conclude that SRL T1/2 is much shorter in children compared with published data on adults, and that children therefore require either higher doses or more frequent dosing to maintain and perhaps improve on acute rejection rates and long-term graft survival. Formal PK studies in children at later post-transplant periods would be of value in determining whether these observations persist beyond early post-transplant months.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant U01-AI46135, NIH grant K23 RR16080 (ADS), NIH NCRR grant MO1 RR02172 (Children’s Hospital Boston, GCRC), NIHNCRR grant RR00240 (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, GCRC), Wyeth Research, and the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS).

References

- 1.Zimmerman J, Kahan B. Pharmacokinetics of sirolimus in stable renal transplant patients after multiple oral dose administration. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:405–415. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brattstrom C, Sawe J, Tyden G, et al. Kinetics and dynamics of single oral doses of sirolimus in sixteen renal transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 1997;19:397–406. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.T ejani A, Alexander S, Ettenger R et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of ascending single doses of sirolimus (Rapamune®, Rapamycin) in pediatric patients with stable chronic renal failure undergoing dialysis. Pediatr Transplant 2004: in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ettenger R, Blifeld C, Prince H, et al. The pediatric nephrologist’s dilemma: growth after renal transplantation and its interaction with age as a possible immunologic variable. J Pediatr. 1987;111:1022–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEnery P, Stablein D, Arbus G, Tejani A. Renal transplantation in children. A report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1727–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206253262602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conley S, Flechner S, Rose G, Vanburen C, Brewer E, Kahan B. Use of cyclosporine in pediatric renal transplant recipients. J Pediatr. 1985;106:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahan B, Kerman R, Wideman C, Flechner S, Jarowenko M, Vanburen C. Impact of cyclosporine on renal transplant practice at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Am J Kid Dis. 1985;5:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(85)80157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benfield M, Symons J, Bynon S, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in pediatric renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 1999;3:33–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.1999.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberti I, Reisman L. A comparative analysis of the use of mycophenolate mofetil in pediatric vs. adult renal allograft recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 1999;3:231–235. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.1999.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filler G, Zimmering M, Mai I. Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolate mofetil are influenced by concomitant immunosuppression. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:100–104. doi: 10.1007/s004670050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearns G. Impact of developmental pharmacology on pediatric study design: overcoming the challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:S128–S138. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarwal M, Yorgin P, Alexander S, et al. Promising early outcomes with a novel, complete steroid avoidance immunosuppression protocol in pediatric renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:13–21. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoppu K, Koskimies O, Holmberg C, Hirvisalo E. Pharmacokinetically determined cyclosporine dosage in young children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1991;5:1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00852828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald R, Ho P, Stablein D, Tejani A. Rejection profile of recent pediatric renal transplant recipients compared with historical controls: a report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS) Am J Transplant. 2001;1:55–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.010111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colombani PM, Dunn SP, Harmon WE, Magee JC, McDiarmid SV, Spray TL. Pediatric transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(Suppl 4):53–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.3.s4.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sindhi R, Webber S, Goyal R, Reyes J, Venkataramanan R, Shaw L. Pharmacodynamics of sirolimus in transplanted children receiving tacrolimus. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1960. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]