Abstract

Escherichia coli YibP protein (47.4 kDa) has a membrane-spanning signal at the N-terminal region, two long coiled-coil regions in the middle part, and a C-terminal globular domain, which involves amino acid sequences homologous to the peptidase M23/M37 family. A yibP disrupted mutant grows in rich medium at 37°C but not at 42°C. In the yibP null mutant, cell division and FtsZ ring formation are inhibited at 42°C without SOS induction, resulting in filamentous cells with multiple nucleoids and finally in cell lysis. Five percent betaine suppresses the temperature sensitivity of the yibP disrupted mutation. The mutant has the same sensitivity to drugs, such as nalidixic acid, ethidium bromide, ethylmethane sulfonate, and sodium dodecyl sulfate, as the parental strain. YibP protein is recovered in the inner membrane and cytoplasmic fractions, but not in the outer membrane fraction. Results suggest that the coiled-coil regions and the C-terminal globular domain of YibP are localized in the cytoplasmic space, not in the periplasmic space. Purified YibP has a protease activity that split the substrate β-casein.

The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli has been determined (1). There are a lot of open reading frames whose biological functions are still unknown. The physiological function of the yibP gene is unknown so far. Computer analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences of YibP showed that YibP protein has a membrane-spanning region, two long coiled-coil regions, and a C-terminal globular domain. The C-terminal domain of YibP has a region homologous to members of the M23/M37 family (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/Pfam/getacc?PF01551).

Members of the peptidase M23/37 family are zinc metallopeptidases with a range of specificities. Members of the M37 family are Gly-Gly endopeptidases (19). Members of the M23 family are also endopeptidases. The M37 family includes some bacterial lipoproteins, such as E. coli NlpD (9, 12), for which no proteolytic activity has been demonstrated. B-lytic endopeptidases are bacterial metallopeptidases that belong to the M23 protease family (Medline entry 95405261). Cleavage is specific for glycine bounds, especially in Gly-Gly-Xaa sequences, where Xaa is any aliphatic hydrophobic residue. B-lytic endopeptidases exist in the cell wall of gram-positive bacteria in which the peptidoglycan cross-links contain glycine residues. These endopeptidases contain zinc, but the exact position of the metal-binding ligands is uncertain.

In this work, we found that yibP disrupted mutant cells were unable to form colonies at 42°C. We report here various properties of yibP disrupted mutant cells and the subcellular localization of the YibP protein. We found that the purified YibP protein had a proteolytic activity for the substrate β-casein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Bacterial cells were grown in L medium (1% Bacto-tryptone, 0.5% Bacto-yeast extract, and 0.5% sodium chloride, pH 7.2) and synthetic medium M9 (16) supplemented with glucose (0.2%) and l-tryptophan (50 μg/ml). Transduction mediated with phage P1 vir was performed according to Miller (16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| W3110 | Wild type | Laboratory strain |

| YK1100 | W3110 trpC9941 | 23 |

| MS8 | F− ΔlacX74 strA araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK hsr hsm+rnhA::cat | 17 |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdS (rB− mB−) gal with the λ phage DE3 lysogen containing the T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of the lacUV5 promoter | 18 |

| CC118 | Δ(araABC-leu)7679 ΔlacX74 ΔphoA20 galE galK thi rpsE rpoB argE(Am) recA1 | 15 |

| CC202 | CC118/F42 lacI3 zzf-2::TnphoA | 15 |

| DF264 | HfrC pgk-2 relA1 pit-10 spoT1 tonA22 T2rzgd-210::Tn10 | A. Nishimura |

| BD18 | HfrH rpsL Δcya-851 Δcrp-96 thi zhd-732::Tn10 | 14 |

| CH1524 | F−trpA36 lysA xyl-4 ilvD130 argH1 zib-137::Tn10 | 13 |

| IT101 | YK1100 rpsL (Smr) | This study |

| IT106 | IT101 yibP::kan | This study |

| IT107 | BL21(DE3) harboring pETY | This study |

| IT110 | IT106(DE3) | This study |

| IT111 | IT110 harboring pETY | This study |

| IT401 | CC118 harboring pIT401 | This study |

| IT402 | CC118 harboring pIT402 | This study |

| IT601 | IT106 (λ)+ | This study |

Isolation of yibP disrupted mutant strain.

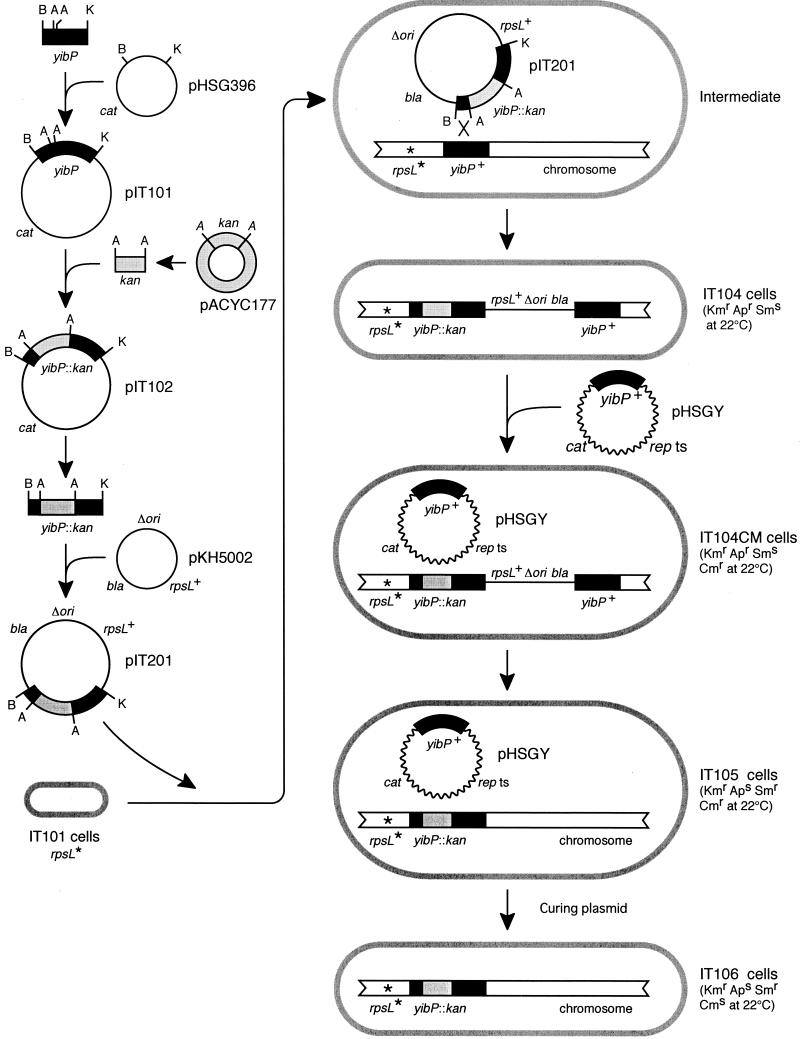

A yibP disrupted mutant strain of E. coli was isolated as follows (Fig. 1). First, the BamHI-KpnI DNA fragment (3,283 bp) containing the wild-type yibP gene from the W3110 chromosome was amplified by PCR and inserted at the BamHI and KpnI sites of plasmid pHSG396, yielding pIT101 (Fig. 1). The kan cassette isolated from pACYC177 (1.4 kb of the Aor51HI DNA segment of pACYC177) was inserted at the Aor51HI sites of the yipP gene in pIT101, yielding pIT102 (Fig. 1). The BamHI-KpnI yibP::kan DNA fragment isolated from pIT102 was inserted at the BamHI and KpnI sites of pKH5002 carrying the wild-type rspL gene, yielding pIT201.

FIG. 1.

Procedures for isolation of a yibP disrupted mutant strain of E. coli (see Materials and Methods). rpsL*, an rpsL mutation conferring streptomycin resistance (the mutant allele is recessive to the wild-type rpsL+ gene). repts, temperature-sensitive rep mutant gene that codes for the initiation protein of plasmid replication. Δori, deletion of the origin region of plasmid replication. bla, kan, and cat, ampicillin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol resistance-conferring genes, respectively. B, BamHI; K, KpnI; A, Aor51HI.

The pKH5002 plasmid is a derivative of the ColE1 plasmid that has lost the replication origin of the replicon (17). Therefore, pKH5002 and its derivative pIT201 are unable to replicate in the wild-type rnh+ strain, but these plasmids can replicate in bacterial cells lacking RNase H, such as bacterial strain MS8. The pIT201 plasmid was introduced into IT101 cells having a streptomycin (Sm)-resistant rpsL mutation and the wild-type rnh+ gene, and then transformants that were kanamycin resistant (Kmr, 30 μg/ml), ampicillin resistant (Apr, 100 μg/ml), and Sms (100 μg/ml) were isolated at 22°C.

A transformant among those was named IT104 (Fig. 1). The IT104 strain might have pIT201 inserted into the bacterial chromosome. The insertion of pIT201 might be performed by a single homologous recombination between the yibP::kan segment of the introduced pIT201 plasmid and the wild-type yibP segment of the host chromosome, because pIT201 could not replicate in host cells with the wild-type rnh+ gene. IT104 therefore has both the wild-type yibP gene and the yibP::kan gene on the chromosome. As the wild-type rpsL+ allele is dominant to the Sm-resistant rpsL mutation, IT104 cells are therefore sensitive to streptomycin. It was unknown whether disruption mutants of the yibP gene are nonviable. We therefore introduced plasmid pHSGY carrying the wild-type yibP gene into IT104 cells at 22°C prior to isolation of yibP disrupted mutants in order to complement the yibP disruption. The resulting bacterial strain was named IT104CM (Fig. 1).

Subsequently, Smr Kmr chloramphenicol-resistant (Cmr) Aps clones were selected at 22°C from IT104CM cells. These clones might lack a DNA segment including the wild-type rpsL+ gene, the bla gene, and the wild-type yibP gene of the chromosome. The deletion of this segment was caused by a single homologous recombination between yibP::kan and yibP segments. Thus, these clones had the yibP::kan gene and lacked the wild-type yibP gene. One of these clones was named IT105 (Fig. 1). To cure the pHSGY plasmid that is unable to replicate at 42°C, IT105 cells were incubated at 42°C for 1 h to inhibit plasmid replication, spread on L agar plates, and incubated overnight at 22°C. Grown colonies were tested for sensitivity to chloramphenicol. Cms Kmr clones that were free of pHSGY were easily obtained. These clones were confirmed by PCR and restriction mapping to carry the yibP::kan mutated gene and to lack the wild-type yibP gene on the chromosome. One of those was named IT106 (Fig. 1). IT106 cells grew below 37°C, but they were nonviable at 42°C, as described precisely in the Results.

Construction of plasmid encoding a YibP-His6 fusion protein.

A DNA segment containing the yibP gene of the W3110 chromosome was amplified together with NdeI and XhoI sites located at the ends by PCR using primers 5′-ATCCCTCCATATGAGGGGAAAGGCGATTAA-3′ and 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCTTCCCAACCACGGCTGTGG-3′. The amplified NdeI-XhoI DNA segment was inserted between the NdeI and XhoI sites of pET-21b plasmid DNA, yielding pETY. The pETY plasmid was confirmed to code for a YibP-His6 fusion protein by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting. The pETY plasmid complemented the temperature sensitivity of the yibP disrupted mutation IT110 in both the presence and absence of IPTG (isopropylthiogalactopyranoside, 1 mM final concentration).

Subcellular fractionation by the Sarkosyl method.

A cell lysate of IT107 was fractionated into three fractions, cytoplasmic, inner membrane, and outer membrane, as follows. IT107 cells were exponentially grown in L medium containing ampicillin (25 μg/ml) at 37°C (without IPTG). Cells were collected by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 15 min) and washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl. The washed cells were suspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6), sonicated, and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 10 min) to remove cell debris. The cleared lysate was centrifuged (157,000 × g, 30 min), and the supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) and the precipitate were isolated. The precipitate was suspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) containing 1.2% sodium lauryl sarcosinate (Sarkosyl) and then centrifuged (157,000 × g, 30 min). The supernatant was kept as the inner membrane fraction. The precipitate was suspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) and kept as the outer membrane fraction. The amount of protein in each fraction was determined by measurement of optical density at 260 and 280 nm with a spectrophotometer. Cytoplasmic, inner membrane, and outer membrane fractions were analyzed for YibP-His6 fusion protein by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. YibP-His6 fusion protein was stained with anti-His tag mouse monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1; Penta-His antibody; Qiagen) as the first antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG polyclonal antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as the second antibody, and a staining kit (NEN Life Science).

Preparation of spheroplasts.

Spheroplasts were prepared from IT111 cells grown in the absence of IPTG by the method of Ito et al. (10). Spheroplasts were incubated with or without proteinase K (1 mg/ml) at 0°C for 2 h, followed by termination of the digestion with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (final concentration, 1 mM) and precipitation of proteins with trichloroacetic acid, according to Kihara et al. (11).

Purification of YibP-His6 fusion protein.

IT107 cells were grown in L medium containing ampicillin (25 μg/ml) at 37°C. IPTG (1 mM) was added at the early exponential phase of the culture, and the culture was incubated for a further 4 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and suspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). The cell suspension was sonicated and fractionated into cytoplasmic, inner membrane, and outer membrane fractions as described above. The YibP-His6 fusion protein in the inner membrane fraction was adsorbed to a nickel-chelating affinity column (HiTrap Chelating HP 5 ml; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and eluted by 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) containing 500 mM imidazole and 500 mM sodium chloride (without Sarkosyl). After the initial solubilization, Sarkosyl was omitted from buffers during purification of YibP-His6. The eluent was desalted through a desalting column (Hi Trap Desalting 5 ml; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) by 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). YibP-His6 fractions were collected and fractionated through a cation exchange column (HiTrap SP 1 ml; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with a gradient (0 to 500 mM) of sodium chloride in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). The purified YibP-His6 sample was adsorbed again in another nickel-chelating affinity column and then eluted with a gradient (0 to 300 mM) of imidazole in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) containing 500 mM sodium chloride. Each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins in gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB).

Analysis of proteolytic activity.

Proteolytic activity of the purified YibP-His6 protein was analyzed as follows. Fifteen microliters of the standard reaction mixture contained the purified YibP-His6 protein (2 μg), β-casein (2 or 4 μg), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM magnesium acetate, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for various times. After the incubation, the reaction mixture was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% gel). After electrophoresis, proteins of gels were stained with CBB. In a control reaction, the purified YibP-His6 protein was replaced by the supernatant of the YibP-His6 sample pretreated with anti-His tag mouse monoclonal IgG1 (Penta-His antibody; Qiagen) and then with protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). To determine N-terminal amino acid sequences, following SDS-PAGE, proteolytic products were blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Polypeptide bands were cut and analyzed for N-terminal amino acid sequences with a Shimadzu PPSQ-23 peptide sequencer.

Analysis of topology of YibP-PhoA fusion proteins.

To determine whether most of YibP except the membrane-spanning region is localized in the cytoplasmic space or periplasmic space, we analyzed as follows. The multicopy plasmid pIT101 carrying the wild-type yibP gene was introduced into CC202 cells harboring the low-copy-number plasmid F42 with the transposon TnphoA, which carries the phoA gene, encoding alkaline phosphatase, and the kan gene (19). A Cmr transformant harboring pIT101 was isolated on L agar plates containing 15 μg of chloramphenicol per ml at 37°C. From this transformant, 20 mutant clones that could grow on L agar plates containing a high concentration (300 μg/ml) of kanamycin were independently isolated at 37°C. In these mutant cells, the transposon had been transferred from the low-copy plasmid F42 to the multicopy plasmid pIT101.

Plasmid DNA isolated from these clones was analyzed by restriction mapping and DNA sequencing to determine the insertion site of TnphoA. Lysates of bacterial cells with yibP::TnphoA mutant plasmids were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% gel) and Western blotting using rabbit anti-PhoA (alkaline phosphatase of E. coli) polyclonal antibodies (Chemicon International Inc.) to detect YibP-PhoA fusion proteins. These mutant clones were tested for colony color on L agar medium containing 300 μg of kanamycin and 40 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (XP) per ml. If the PhoA (alkaline phosphatase) domain of the YibP-PhoA fusion protein is localized in the periplasmic space, the bacterial strain forms blue colonies on this medium (15).

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy.

The FtsZ ring was observed by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (6) using rabbit anti-FtsZ polyclonal antibodies (gift from Lawrence I. Rothfield).

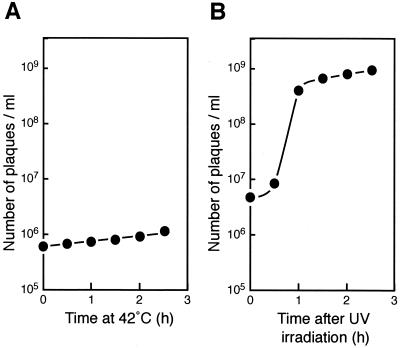

Induction of lysogenized phage λ.

To examine the effect of a temperature shift to 42°C, cells of the lambda phage-lysogenized strain IT601 grown exponentially in L medium at 30°C were transferred to 42°C, and samples were removed at 30-min intervals for 2.5 h, diluted, and spread together with indicator YK1100 cells by the soft agar layer method on L agar plates. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and plaques were counted. To examine the effect of UV irradiation, cells of the same strain grown at 30°C were irradiated by UV (15 W, 50 cm, 5 min) and incubated at 37°C in L medium. Samples were removed at 30-min intervals and treated immediately with chloroform, and cell lysates were analyzed for the number of active phage particles by the soft agar layer method described above.

RESULTS

Prediction of structure of YibP protein.

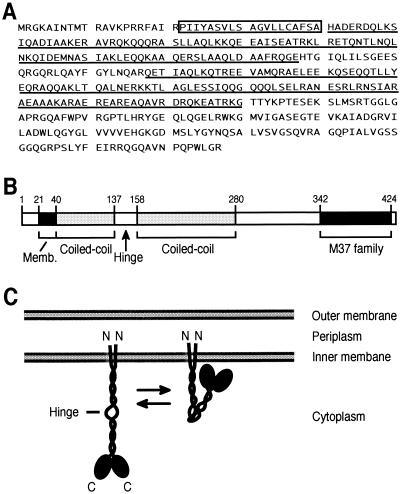

Computer search (http://shigen.lab.nig.ac.jp/ecoli/pec/) of deduced amino acid sequences of YibP (427 amino acids, 47.4 kDa) suggested that YibP has a membrane-spanning signal (Pro22 to Ala40) at the N-terminal region, two long coiled-coil regions (http://spock.genes.nig.ac.jp/∼genome/gtop-j.html) in the middle part of the protein, and a C-terminal globular domain (Fig. 2A and B). Computer analysis (http://www.ch.embnet.org/GeneratedItems/EPScript.js) suggested that the N-terminal end of the membrane-spanning signal is located in the periplasm and the C-terminal end is located in the cytoplasm.

FIG. 2.

Predicted structure of YibP protein. (A) Amino acid sequence of YibP (1). The membrane-spanning region is boxed. Coiled-coil regions are underlined. The region from amino acids 342 to 424 has homology to members of the peptidase M37 family (http://pfam.wustl.edu/). (B) Predicted domains of YibP protein. (C) Model of the homodimer of YibP.

The region from amino acids 342 to 424 is homologous to members of the peptidase M37 family (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/Pfam/getacc?PF01551) (19). Typical zinc-binding (see Discussion) and nucleotide-binding (8, 22) sequences were not found in YibP. From these results, we propose a model for the structure of YibP (Fig. 2C). YibP has two long coiled-coil regions of different lengths. YibP is presumed to form homodimer in these coiled-coil regions with parallel arrangement, not antiparallel arrangement. A homodimer of YibP would be anchored by the membrane-spanning region in the inner membrane. The most region of YibP except the membrane-spanning region would be located in the cytoplasm. The homodimer of YibP can bend at a hinge existing between the coiled-coil rod regions. This model was consistent with the experimental results as described below.

Properties of yibP null mutant.

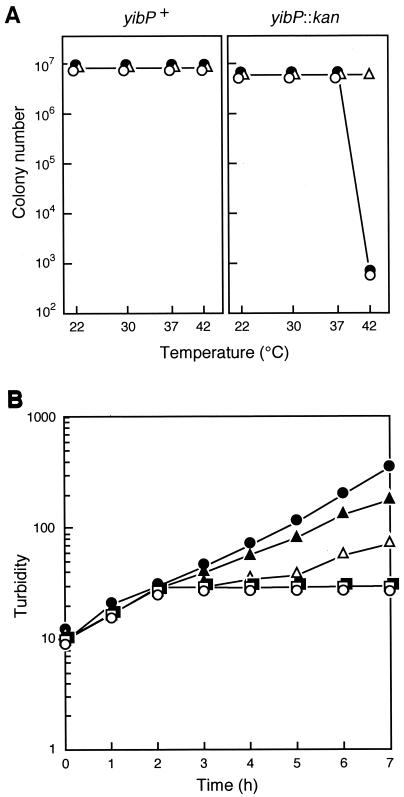

We isolated a yibP null mutant strain, IT106, as described in Materials and Methods. The yibP null mutant was able to form colonies at 37°C and below 37°C but not at 42°C on L agar plates (0.5% sodium chloride) (Fig. 3A). To increase the osmotic pressure of the medium, we added betaine (glycinebetaine) (4) to the medium. The addition of 5% betaine but not 1% betaine (4) suppressed the temperature-sensitive colony formation of yibP disrupted mutant cells (Fig. 3A). The temperature-sensitive colony formation was also suppressed in the presence of 1% salts, NaCl, KCl, or NaCl plus KCl, in L agar medium (data not shown). Furthermore, the addition of 10% sucrose to the L medium suppressed the temperature-sensitive colony formation (data not shown). On the other hand, 10% glucose did not suppress the temperature sensitivity. These results suggest that YibP is required for survival at 42°C in environments of low osmotic pressure.

FIG. 3.

(A) Effect of betaine on temperature-sensitive colony formation of wild-type yibP+ cells (left) and yibP-disrupted mutant cells (right) in L agar medium. Solid circles, no betaine; open circles, 1% betaine; open triangles, 5% betaine. (B) Growth of yibP-disrupted mutant cells at various temperatures in L medium. Bacterial cells of IT106 were exponentially grown at 30°C and divided into six subcultures at time zero. Each subculture was further incubated as follows: solid circles, 30°C; open circles, 42°C; solid triangles, 42°C for 1 h and then transfer to 30°C; open triangles, 42°C for 2 h and then transfer to 30°C; solid squares, 42°C for 3 h and then transfer to 30°C; open squares, 42°C for 4 h and then transfer to 30°C.

When yibP null mutant cells grown exponentially in L medium at 30°C were transferred to 42°C, an increase in the turbidity of the culture was inhibited after 2 h (Fig. 3B). After the temperature shift, cells became elongated, resulting in smooth filamentous cells with multiple nucleoids (Fig. 4A). Two hours after the shift, a small portion of filamentous cells were lysed. Four hours after the shift, the majority of filamentous cells were lysed; however, the subpopulation continued to elongate, and therefore the turbidity of the culture did not decrease markedly. When a subculture was incubated at 42°C for 1 h and then transferred back to 30°C, turbidity increased slightly and slowly compared to that of a subculture incubated continuously at 30°C. When subcultures were incubated at 42°C for more than 2 h and then transferred to 30°C, increase in turbidity was markedly inhibited (Fig. 3B). Thus, cells became filaments and nonviable during long incubation at 42°C.

FIG. 4.

Effect of temperature shift to 42°C on morphology of cells and FtsZ ring formation. Bacterial cells of IT101 and IT106 were exponentially grown at 30°C and transferred to 42°C (time zero), and samples were removed at intervals and analyzed. (A) Cells were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) according to Hiraga et al. (7). (B) Cells were analyzed for the subcellular localization of FtsZ by indirect fluorescence microscopy (6).

To examine whether cell division is indirectly inhibited by SulA/SfiA induced by the SOS response at 42°C (21), we analyzed a yibP mutant strain lysogenized with the wild-type λ phage (strain IT601). When cells of the strain were incubated at 42°C, the phage was not induced (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the phage was induced in the same strain after UV irradiation (Fig. 5B). Thus, the inhibition of cell division observed in the yibP disrupted mutant strain is not due to the SOS response.

FIG. 5.

Different effects of temperature shift and UV irradiation on induction of phage λ-lysogenized strain IT601. (A) Temperature shift to 42°C. (B) UV irradiation. See Materials and Methods for details.

We analyzed FtsZ ring formation in the yibP null mutant cells after a temperature shift to 42°C. Before the temperature shift, a single FtsZ ring was observed at the middle position of the cell in more than 95% of the yibP null mutant cells as in parental wild-type cells (Fig. 4). However, after incubation for 2 h at 42°C, smooth filamentous cells with multinucleoids had no FtsZ ring (90% of the cells) or only one FtsZ ring (10%). The single FtsZ ring was asymmetrically localized at about 2 μm from a cell pole in filamentous cells, suggesting that ring localization was abnormal. Similar asymmetrical localization of an FtsZ ring has been found in another temperature-sensitive mutant, hscA (20). FtsZ ring formation was thus inhibited at 42°C in the yibP null mutant. In contrast, most cells of the parental strain IT101 had one FtsZ ring at the middle of the cell at 42°C (Fig. 4B). There was no difference between the yibP null mutant cells and the isogenic wild-type cells in sensitivity to drugs, such as ethidium bromide, sodium dodecyl sulfate, rifampin, nalidixic acid, novobiocin, and methyl methanesulfonate, suggesting that the yibP disruption mutation does not affect membrane transport of these drugs.

A plasmid carrying a mutated yibP gene lacking the codons encoding the C-terminal 147 amino acids (Gly280 to Arg427) was unable to complement the temperature sensitivity of the yibP null mutant IT106, suggesting that the C-terminal region in the homologous domain of the M37 family is important for the in vivo function of YibP.

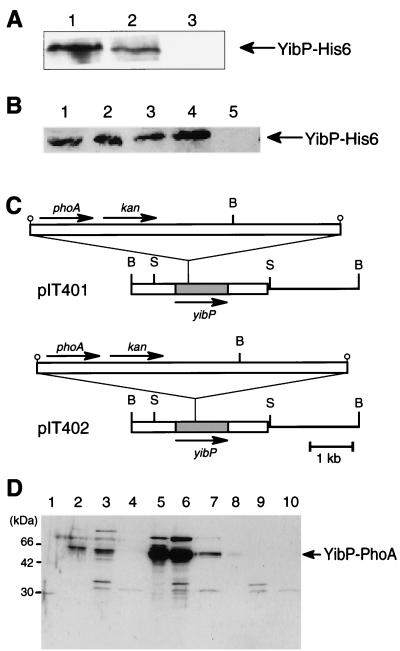

Subcellular localization of YibP-His6.

To examine the subcellular localization of YibP-His6, we fractionated the cell lysate of strain IT107 into cytoplasmic, inner membrane, and outer membrane fractions by the Sarkosyl method. YibP-His6 was recovered in the inner membrane and cytoplasmic fractions, but not in the outer membrane fraction (Fig. 6A). These results support the above model that YibP-His6 is inserted into the inner membrane at its membrane-spanning region.

FIG. 6.

(A) Localization of the YibP-His6 fusion protein in cellular fractions. Cell extract of IT107 was fractionated into three fractions by the Sarkosyl method, and these fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-His tag antibody. Each sample containing 10 μg of protein was applied to the gel. Lane 1, cytoplasmic fraction. Lane 2, inner membrane fraction. Lane 3, outer membrane fraction. (B) Effect of incubation with and without proteinase K on spheroplasts prepared from IT111 cells. Lane 1, total proteins of cells precipitated with trichloroacetic acid. Lane 2, spheroplasts. Lane 3, sonicated spheroplasts. Lane 4, spheroplasts incubated with proteinase K. Lane 5, sonicated spheroplasts incubated with proteinase K. (C) Insertion site of the TnphoA transposon in plasmids. B, BamHI; S, SacI. (D) C118 cells harboring pIT401 and pIT402 were exponentially grown in the absence of IPTG. Cell fractions prepared by the Sarkosyl method were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% gel) and Western blotting using anti-PhoA antibody. Lane 1, molecular size markers. Lanes 2 to 4, cellular fractions of cells with pIT401. Lanes 5 to 7, cellular fractions of cell with pIT402. Lanes 8 to 10, cellular fractions of cells without plasmid. Lanes 2, 5, and 8, cytoplasmic fraction. Lanes 3, 6, and 9, inner membrane fraction. Lanes 4, 7, and 10, outer membrane fraction.

To examine whether YibP is localized in the periplasmic space or the cytoplasmic space, we prepared spheroplasts from IT107 and either treated them with proteinase K or did not treat them with proteinase K. YibP-His6 was resistant to the protease treatment (Fig. 6B). In sonicated spheroplasts, YibP-His6 was completely digested with proteinase K. These results indicate that YibP-His6 is located in the cytoplasmic space. To confirm the conclusion, we isolated bacterial clones harboring plasmids with transferred Tn10phoA as described in Materials and Methods. We examined these clones for the expression of YibP-PhoA fusion protein and for DNA sequences of their plasmids and found that plasmid pIT401 codes for a 60.5-kDa YibP-PhoA fusion protein (Met1 to Met87 of YibP) and that pIT402 codes for a 66.6-kDa YibP-PhoA fusion protein (Met1 to Tyr162 of YibP) (Fig. 6C). These fusion proteins were recovered from the inner membrane fraction and the cytoplasmic fraction, but not from the outer membrane fraction (Fig. 6D). IT401 and IT402 bacterial cells with these plasmids (Table 1) formed white colonies on the XP-containing L agar medium. The PhoA domain of these YibP-PhoA fusion proteins is therefore localized in the cytosolic space, not the periplasmic space. These results support the above model that the coiled-coil regions of YibP are located in the cytoplasmic space (Fig. 2C).

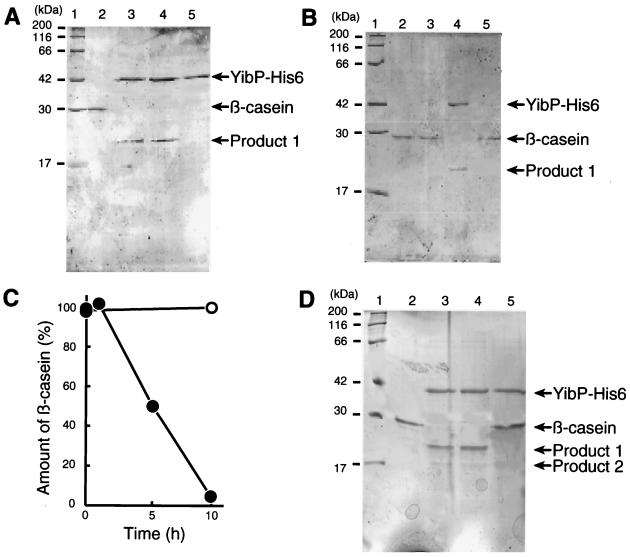

Protease activity of YibP-His6 fusion protein.

The purified YibP-His6 protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The YibP-His6 fusion protein (48.3 kDa) migrated at the same position as a 42-kDa molecular marker protein in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7A). The protein sample had more than 95% purity for YibP (data not shown). The purified YibP-His6 protein had a protease activity that split β-casein (Fig. 7). A proteolytic product (ca. 20 kDa) was detected in the experiment (Fig. 7). No effect of the addition of ATP and zinc ion was observed in the proteolysis of β-casein (Fig. 7A). Omission of magnesium acetate did not affect the proteolytic activity, but the addition of 10 mM EDTA inhibited the activity completely (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

Degradation of β-casein by the purified YibP-His6 fusion protein. The standard reaction mixture was described in Materials and Methods. Proteins of the gel were stained with CBB. (A) Lane 1, molecular size markers. Lane 2, without YibP-His6. Lane 3, addition of 1 mM ATP and 25 μM zinc acetate. Lane 4, standard reaction mixture (2 μg of β-casein). Lane 5, without β-casein. All the samples (lanes 2 to 5) were incubated for 10 h at 37°C. (B) Lane 1, molecular size makers. Lane 2, without YibP-His6 (time zero). Lane 3, without YibP-His6. Lane 4, standard reaction mixture. Lane 5, without YibP-His6 and with the supernatant of the YibP-His6 sample treated with anti-His tag mouse monoclonal IgG1 and protein A-Sepharose. Reaction mixtures (lanes 3 to 6) were incubated for 10 h at 37°C. (C) Time course of the reaction. Solid circles, with YibP. Open circles, without YibP. (D) Reaction mixtures containing 4 μg of β-casein were incubated for 10 h at 37°C. Lane 1, molecular size markers. Lane 2, β-casein. Lane 3, standard reaction mixture (4 μg of β-casein). Lane 4, without magnesium acetate. Lane 5, without magnesium acetate and with 10 mM EDTA.

To eliminate the possibility that the proteolytic activity was due to a putative minor protein contaminant in the purified YibP-His6 sample, we treated the YibP-His6 sample with anti-His tag mouse monoclonal IgG1 and protein A-Sepharose. After centrifugation, we used the supernatant for the reaction and found no proteolytic activity for β-casein (Fig. 7B, lane 5). These results indicate that YibP-His6 itself exhibits the proteolytic activity for β-casein.

Τhe substrate β-casein was nearly completely digested after incubation for 10 h at 37°C (Fig. 7C). When a reaction mixture containing a high concentration (4 μg/ml) of β-casein was incubated for 10 h, two proteolytic products of 20 and 17 kDa were detected (Fig. 7D). We analyzed these proteolytic products and the substrate β-casein for the N-terminal amino acid sequences. Both the 20-kDa and 17-kDa products had the sequence RELEELNV at the N-terminal end. The β-casein sample also had the same sequence, indicating that the substrate sample used had lost the N-terminal 15 amino acid residues, MKVLILACLVALALA. When α-casein was used as the substrate for YibP, the proteolytic activity was not observed (data not shown). The α-casein sample had the N-terminal sequence RPKHPIKH, suggesting that the sample had lost the N-terminal 15 amino acid residues, MKLLILTCLVAVALA. Note that YibP itself was not degraded during incubation for 10 h.

DISCUSSION

The present results suggest that YibP protein is anchored at the N-terminal membrane-spanning region in the inner membrane and that the coiled-coil-hinge-coiled-coil regions exist in the cytoplasm, not the periplasm. The C-terminal globular domain containing the M23/M37 homologous region might be also located in the cytoplasm, because only one predicted membrane-spanning region exists at the N-terminal region of YibP.

YibP is presumed to have pleiotropic physiological effects in the cell. Inhibition of FtsZ ring formation at 42°C may be one of the pleiotropic effects caused by the absence of YibP. The addition of salt, sucrose, and betaine to the medium suppressed the temperature sensitivity of yibP null mutant cells. YibP is therefore required for survival in environments of high temperature and low osmotic pressure. Isolation of yibP null mutants at 42°C by another method failed (T. Miki, personal communication), being consistent with our results.

In this work, we found that the purified YibP-His6 fusion protein had a proteolytic activity that split β-casein. Members of the M23/M37 family are zinc metallopeptidases. Bacterial metallopeptidases of this family contain zinc, but the exact position of the metal-binding ligands is uncertain. On the basis of similarity with d-Ala-d-Ala-carboxypeptidase, it has been suggested that a conserved His-X-His motif (where X is any amino acid) forms part of the binding site (Medline 95405261). However, YibP does not have the His-X-His motif. The presence of EDTA in the reaction mixture inhibited the proteolytic activity of YibP (Fig. 7D), suggesting the possibility that YibP involves a metallo-ion.

We have searched for homologues of YibP in the prokaryotic genome sequences available so far. YibP homologues that have the membrane-spanning region, long coiled-coil regions, and the C-terminal globular domain have been found in members of the γ and β subdivisions of the gram-negative proteobacteria. The sequence from amino acids 342 to 424 of YibP is homologous to that of members of the peptidase M23/M37 family as described above. E. coli proteins encoded by yebA, nlpD (9, 12), and b2865 have a domain homologous to the peptidase M37 domain, but lack long coiled-coil regions. A YebA homologue from Bacillus subtilis was described (2). No proteolytic activity has been demonstrated for E. coli NlpD, a membrane lipoprotein (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/Pfam/swisspfamget.pl?name=NLP_ECOLI). YibP is thus a new type of endopeptidase.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pHSG396 | Cmr; cloning vector | Takara |

| pACYC177 | Kmr; ColE1 cloning vector | 3 |

| pKH5002 | Apr; Δori rpsL+ | 17 |

| pHSG415s | Cmr; temperature-sensitive plasmid | 5 |

| pET21b | Apr; T7 promoter vector | Novagen |

| pACYC184 | Cmr Tcr; ColE1 cloning vector | 3 |

| pIT101 | Cmr; yibP cloned at BamHI and KpnI sits of pHSG396 | This study |

| pIT102 | Cmr Kmr; kan cassette inserted at Aor51HI sites of pIT101 | This study |

| pIT201 | Apr Kmr; BamHI-KpnI yibP::kan segment inserted at BamHI and KpnI sites of pKH5002 | This study |

| pHSGY | Cmr; yibP fragment inserted at PstI and SmaI sites of pHSG415s | This study |

| pETY | Apr; yibP fragment inserted at NdeI and XhoI sites of pET21b | This study |

| pIT401 | Cmr; TnphoA inserted in yibP of pIT101 | This study |

| pIT402 | Cmr; TnphoA inserted in yibP of pIT101 | This study |

Acknowledgments

We thank Jun-ichi Kato, Haruo Ohmori, Akiko Nishimura, and Lawrence I. Rothfield for bacterial strains, plasmids, and antibodies. We also thank Tateyoshi Miki, Hirotada Mori, Teru Ogura, Kunitoshi Yamanaka, Yukiko Yamazaki, and Ken Nishikawa for suggestion and discussion. We also thank Chiyome Ichinose, Yuki Kawata, and Mizuho Yano for assistance in the laboratory.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture, and Technology of Japan, Japan Society for Promotion of Science, and CREST.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett 3rd, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borriss, R., S. Porwollik, and R. Schroeter. 1996. The 52 degrees-55 degrees segment of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome: a region devoted to purine uptake and metabolism, and containing the genes cotA, gabP and guaA and the pur gene cluster within a 34960 bp nucleotide sequence. Microbiology 142:3027-3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, A. C. Y., and S. N. Cohen. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csonka, L. N., and W. Epstein. 1996. Osmoregulation, p. 1210-1223. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Renznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto-Gotoh, T., F. C. Franklin, A. Nordheim, and K. N. Timmis. 1981. Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. I. Low copy number, temperature-sensitive, mobilization-defective pSC101-derived containment vectors. Gene 16:227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiraga, S., C. Ichinose, H. Niki, and M. Yamazoe. 1998. Cell cycle-dependent duplication and bidirectional migration of SeqA-associated DNA-protein complexes in E. coli. Mol. Cell 1:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiraga, S., H. Niki, T. Ogura, C. Ichinose, H. Mori, B. Ezaki, and A. Jaffé. 1989. Chromosome partitioning in Escherichia coli: novel mutants producing anucleate cells. J. Bacteriol. 171:1496-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houten, B. U. V. 1990. Nucleotide excision repair in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 54:18-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichikawa, J. K., C. Li, J. Fu, and S. Clarke. 1994. A gene at 59 minutes on the Escherichia coli chromosome encodes a lipoprotein with unusual amino acid repeat sequences. J. Bacteriol. 176:1630-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito, K., T. Sato, and T. Yura. 1977. Synthesis and assembly of the membrane proteins in E. coli. Cell 11:551-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kihara, A., Y. Akiyama, and K. Ito. 1997. Host regulation of lysogenic decision in bacteriophage λ: transmenbrane modulation of FtsH (HflB), the cII degrading protease, by HflKC (HflA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5544-5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange, R., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1994. The nlpD gene is located in an operon with rpoS on the Escherichia coli chromosome and encodes a novel lipoprotein with a potential function in cell wall formation. Mol. Microbiol. 13:733-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, R. J., and C. W. Hill. 1983. Mapping the xyl, mtl, and lct loci in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 156:914-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacLachlan, P. R., and K. E. Sanderson. 1985. Transformation of Salmonella typhimurium with plasmid DNA: differences between rough and smooth strains. J. Bacteriol. 161:442-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manoil, C., and J. Beckwith. 1985. TnphoA, a transposon probe for protein export signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:8129-8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics . Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Ohmori, H., M. Saito, T. Yasuda, T. Nagata, T. Fujii, M. Wachi, and K. Nagai. 1995. The pcsA gene is identical to dinD in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:156-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Studier, F. W., A. H. Rosenberg, J. J. Dunn, and J. W. Dubendorff. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185:60-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugai, M., T. Fujiwara, T. Akiyama, M. Ohara, H. Komatsuzawa, S. Inoue, and H. Suginaka. 1997. Purification and molecular characterization of glycylglycine endopeptidase produced by Staphylococcus capitis EPK1. J. Bacteriol. 179:1193-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uehara, T., H. Matsuzawa, and A. Nishimura. 2001. HscA is involved in the dynamics of FtsZ-ring formation in Escherichia coli K12. Genes Cells 6:803-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker, G. W. 1996. The SOS response of Escherichia coli. p. 1400-1416. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Renznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker, J. E., M. Saraste, M. J. Runswick, and N. J. Gay. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamanaka, K., T. Ogura, H. Niki, and S. Hiraga. 1996. Identification of two new genes, mukE and mukF, involved in chromosome partitioning in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250:241-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]