Abstract

Although very little replication past a T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer normally takes place in Escherichia coli in the absence of DNA polymerase V (Pol V), we previously observed as much as half of the wild-type bypass frequency in Pol V-deficient (ΔumuDC) strains if the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease proofreading activity of the Pol III ɛ subunit was also disabled by mutD5. This observation might be explained in at least two ways. In the absence of Pol V, wild-type Pol III might bind preferentially to the blocked primer terminus but be incapable of bypass, whereas the proofreading-deficient enzyme might dissociate more readily, providing access to bypass polymerases. Alternatively, even though wild-type Pol III is generally regarded as being incapable of lesion bypass, proofreading-impaired Pol III might itself perform this function. We have investigated this issue by examining dimer bypass frequencies in ΔumuDC mutD5 strains that were also deficient for Pol I, Pol II, and Pol IV, both singly and in all combinations. Dimer bypass frequencies were not decreased in any of these strains and indeed in some were increased to levels approaching those found in strains containing Pol V. Efficient dimer bypass was, however, entirely dependent on the proofreading deficiency imparted by mutD5, indicating the surprising conclusion that bypass was probably performed by the mutD5 Pol III enzyme itself. This mutant polymerase does not replicate past the much more distorted T-T (6-4) photoadduct, however, suggesting that it may only replicate past lesions, like the T-T dimer, that form base pairs normally.

The discovery that Escherichia coli possesses two new DNA polymerases, Pol IV and Pol V (26, 32, 38), in addition to the three that had been previously identified (18) raises the questions of why E. coli needs five DNA polymerases and what the cellular functions of each might be. At present, it is believed that DNA Pol III is responsible mainly for the replication of undamaged templates, that Pol I participates in filling gaps between Okazaki fragments and those generated during nucleotide excision repair (7, 18), and that Pol II participates in replication restart after UV irradiation (25). In addition, Pol II, along with Pol IV and Pol V, has been implicated in translesion replication (TR) (22, 31). However, in many cases, such roles appear to be polymerase and lesion specific. For example, previous observations (31, 36) have suggested that TR past a site-specific cis-syn cyclobutane thymine-thymine dimer in excision-defective E. coli strains is almost entirely dependent on the activity of DNA polymerase V (Pol V), encoded by the umuDC operon. Curiously, however, we also observed that efficient TR past cis-syn cyclobutane dimers occurs in SOS-induced ΔumuDC cells lacking Pol V, if the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease proofreading activity of the DNA polymerase III ɛ subunit is inactivated by the mutD5 mutation (36). Indeed, 26% TR occurred in UV-irradiated uvrA6 ΔumuDC mutD5 cells, about half the frequency found in similarly treated isogenic uvrA6 umuDC+ mutD5 cells. Most of the TR seen in the uvrA6 ΔumuDC mutD5 cells was damage inducible, with 70% being LexA dependent, and the remainder being LexA independent. A variety of possible circumstances might explain these observations. The lack of TR in proofreading-proficient ΔumuDC strains might imply that, in the absence of competing Pol V, Pol III outcompetes all remaining polymerases in binding to blocked termini of nascent DNA strands but is itself incapable of TR; inactivation of proofreading might then reduce such binding affinity, allowing access to the primer terminus for LexA-regulated bypass enzymes, such as Pol II and Pol IV, or possibly to the repair enzyme, Pol I. Alternatively, although Pol III is thought to be incapable of lesion bypass and only carry out replication of the undamaged genome, it is possible that the observed TR is, in fact, performed by the proofreading-deficient Pol III itself.

We have investigated this question by measuring TR past a T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer in a set of isogenic uvrA6 ΔumuDC mutD5 strains in which the genes encoding DNA polymerases I, II, and IV have been deleted either individually or multiply, in all combinations. We find that TR past the dimer in the uvrA6 ΔumuDC mutD5 strain depends on none of these enzymes, either individually or collectively; indeed, TR is increased in the absence of some of them. Instead, TR appears to depend on the proofreading-deficient Pol III enzyme itself. About 40% of the TR occurred in a mutD5 strain lacking all known DNA polymerases except Pol III, but in contrast, <2% of the TR was observed in its isogenic dnaQ+ counterpart. These observations therefore support the model first suggested nearly 25 years ago, which proposes that TR might simply be achieved through the inactivation of exonucleolytic proofreading (37). However, such a model would appear to be applicable only to DNA lesions that do not grossly distort DNA, as we find that Pol III remains incapable of replicating past the much more distorting T-T pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidinone photoadduct, even if its proofreading activity is much reduced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and F′ episomes.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Where noted, strains were constructed by generalized P1 transduction with P1 vir. Strains used in the M13 plaque assays also contained an F′ for phage propagation. The F′ was either F′ PolA 5′-3′ exo::cat (13), F128 [Φ(lacI133-lacZ) proAB+ dinB::Kan] (P. Foster, personal communication), or DH5αF′IQ (F′ proAB+ lacIqΔM15 zzf::Tn5) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Because the mutD5 allele confers a high spontaneous mutator activity, it was introduced into the strains at the last stage of construction. Although they are not directly utilized in these studies, we have also listed the isogenic dnaQ+ derivatives of the polymerase-deficient strains, and like all strains listed in Table 1, these are available upon request (woodgate@helix.nih.gov).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| CJ231a | ΔpolA::Kan | 13 |

| EYT2 | ΔdinB::Kan | H. Ohmori and E. Ohashi |

| STL1336 | ΔpolB::ΩSpc | 25 |

| FC1233b | Δ(lac-pro) nalA metB argE(Am) thi RifrsuB | P. Foster |

| KM22 | ΔrecBCD::plac-red | 21 |

| AR25 | ΔrecBCD::plac-red ΔdinB61::ble | This study |

| RW118 | recA+lexA+sulA211 | 12 |

| AR30 | ΔdinB61::ble | P1.AR25 × RW118 |

| NR9458 | mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | 27 |

| TK603c | uvrA6 | 14 |

| DV12c, d | uvrA6 mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | 36 |

| RW82c, e | uvrA6 ΔumuDC595::cat | 39 |

| EC8c, e | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT | 6 |

| DV05c, d | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | 36 |

| RW532c, e | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT lexA3(Ind−) | R. Woodgate |

| DV13c, d | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT lexA3(Ind−) mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | 36 |

| DV08c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolB::ΩSpc | 36 |

| DV10c, d | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolB::ΩSpc mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | 36 |

| RW536a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan | P1.C231 × EC8 |

| DV34a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | P1.NR9458 × RW536 |

| DV22c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔdinB::Kan | P1.EYT2 × EC8 |

| DV42b, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔdinB::Kan mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | P1.NR9458 × DV22 |

| RW600a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan ΔpolB::ΩSpc | P1.STL1336 × RW536 |

| DV36a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan ΔpolB::ΩSpc mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | P1.NR9458 × RW600 |

| DV46a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan ΔdinB61::ble | P1.AR25 × RW536 |

| DV40a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan ΔdinB61::ble mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | P1.NR9458 × DV46 |

| DV44c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolB::ΩSpc ΔdinB61::ble | P1.AR25 × DV08 |

| DV30b, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolB::ΩSpc ΔdinB61::ble mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | P1.NR9458 × DV44 |

| DV38a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan ΔpolB::ΩSpc ΔdinB61::ble | P1.AR25 × RW600 |

| DV32a, c | uvrA6 ΔumuDC596::ermGT ΔpolA::Kan ΔpolB::ΩSpc ΔdinB61::ble mutD5 zaf-13::Tn10 | P1.NR9458 × DV38 |

Strain also carries F′ PolA 5′-3′ exo::cat (pCJ102) for viability in rich medium (13).

Strain contains F128 [Φ(lacI133-lacZ) proAB+ dinB::Kan].

Full genotype: uvrA6 thi-1 thr-1 araD-14 leuB6 lacY1 ilv323ts Δ(gpt-proA)62 mtl-1 xyl-5 rpsL31 tsx-33 supE44 galK2(Oc) hisG4(Oc) rfbD1 kdgK51.

Strains carry F′IQ (F′ proAB+ lacIqΔM15 zzf::Tn5) from DH5αF′IQ (Invitrogen).

Construction of a novel dinB substitution allele.

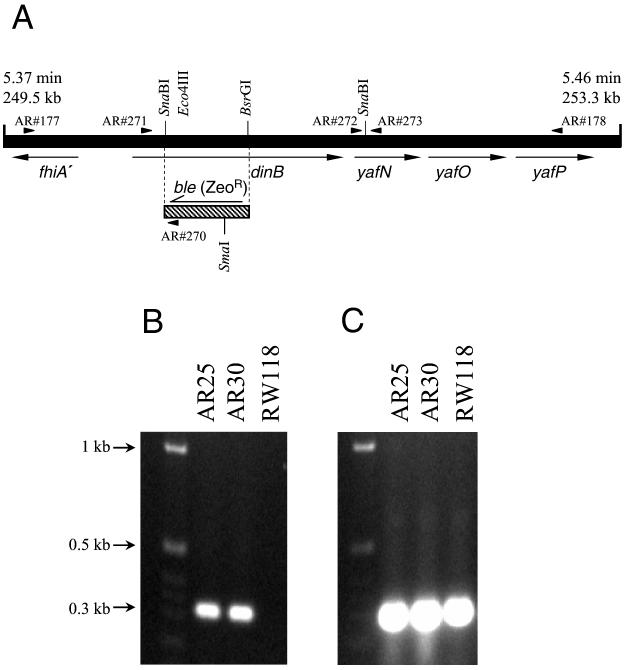

The common dinB substitution alleles encode resistance to either kanamycin or chloramphenicol (17; H. Ohmori and E. Ohashi, personal communication); this precludes their use in strains that are already kanamycin or chloramphenicol resistant, such as the ΔpolA strains. As a consequence, we have generated a novel dinB allele in which part of the dinB coding region has been replaced by a gene encoding resistance to bleomycin and zeomycin (Zeocin; Invitrogen). The strategy used to make the novel dinB allele is as follows. The dinB gene was amplified as a 3,265-bp PCR fragment from the chromosome of strain RW118 (dinB+) by using primers AR#177 (5′CCGTCGCCGATGGTCATCAGCACATACTGC-3′) and AR#178 (5′-CTGGCAACCCCACGGCGGGTGTATTCAGGG-3′) (Fig. 1A). The temperature profile used with these primers was 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 4 min. The PCR product was cloned into the pGEMTeasy plasmid (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and subsequently digested with Eco47III and BsrGI. The recessed end generated by BsrGI was filled in by T4 DNA polymerase in the presence of all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and a similarly blunt-ended 501-bp PstI-SalI fragment from plasmid pUTSV1 (Cayla, Toulouse, France) was ligated into the linearized vector, so as to produce a dinB substitution allele in which 443 bp of dinB are replaced with the Streptoalloteichus hindustanus bleomycin gene encoding resistance to bleomycin and zeomycin (9) (Fig. 1A). After consulting with Mary Berlyn at the E. coli Genetic Stock Center, it has been agreed that the dinB substitution allele be officially identified as ΔdinB61::ble. For simplicity's sake, we will also refer to the allele as ΔdinB::Zeo. The resulting plasmid was digested with NotI, and the approximately 3-kb fragment containing the ΔdinB::Zeo allele was gel purified and used to transform E. coli KM22. KM22 recombines linear DNA into its chromosome with high efficiency, making it a very useful E. coli strain in which to generate null mutants (21). Transformants that were resistant to 25 μg of zeomycin per ml were assayed for the ability to generate a 318-bp PCR fragment with primers AR#270 (5′-GCCATGACCGAGATCGGCGAGCAGCC-3′) and AR#271 (5′-TGTATACTTTACCAGTGTTGAGAGG-3′). The temperature profile used with these primers was 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. AR#270 anneals inside the ble gene, while AR#271 anneals to the 5′ end of the dinB gene. As a consequence, a PCR product is obtained only if the Zeo cassette is inserted within the region of dinB corresponding to the N-terminal part of its product. One representative strain, called AR25, from which we amplified the appropriate PCR fragment, was chosen for further study (Fig. 1B). A P1 lysate was grown on AR25, and the lysate was used to transduce the ΔdinB::Zeo allele into a variety of different genetic backgrounds. An example is AR30, which is a ΔdinB::Zeo derivative of the recA+ lexA+ strain, RW118 (12).

FIG. 1.

(A) Cartoon of the E. coli chromosome containing the dinB-yafN-yafO-yafP operon (black bar). The precise location of the operon within the chromosome is given above the bar in kilobases and in minutes. The direction of gene transcription is depicted by arrowheads. The Eco47III-BsrGI dinB interval was replaced by the S. hindustanus bleomycin gene (Zeo cassette) (diagonally hatched bar) as shown by dashed lines. Relevant restriction enzyme sites are shown, and the key oligonucleotide PCR primers used to construct and analyze the ΔdinB61::ble substitution allele are indicated with small arrows above the black bar. (B) PCR products obtained with primers AR#270 and AR#271 (location shown in panel A). Strains AR25 and AR30, containing the ΔdinB61::ble allele, gave a 318-bp PCR product, indicating that the Zeo cassette is appropriately located within the dinB gene. As expected, the wild-type dinB+ strain, RW118, failed to amplify a fragment. (C) RT-PCR products obtained with primers AR#272 and AR#273 (location shown in panel A). All three strains (AR25 [ΔdinB::Zeo], AR30 [ΔdinB::Zeo], and RW118 [dinB+]) gave 284-bp RT-PCR products of similar intensities. As the primers are located within the yafN gene, which is 3′ to dinB (panel A), we conclude that the ΔdinB61::ble allele does not have any polar effect on the downstream genes within the dinB-yafN-yafO-yafP operon.

dinB is the first gene of an operon that includes yafN, yafO, and yafP (Fig. 1A). To demonstrate that the ΔdinB61::ble substitution allele is nonpolar, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed with total RNA obtained from mitomycin C-treated AR25, AR30, and RW118 cells. By using the internal yafN primers AR#272 (5′-ATGCATCGAATTCTCGCTG-3′) and AR#273 (5′-AAAGTCATTGAAATCATCATCCGTC-3′) (the temperature profile used with these primers was 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min), a 284-bp product of similar intensity was amplified from the two ΔdinB::Zeo strains, AR25 and AR30, as well as from the dinB+ strain, RW118 (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that the ΔdinB61::ble allele is nonpolar and that the substitution has little to no effect on the downstream genes in the dinB-yafN-yafO-yafP operon.

Single lesion vectors.

Single-stranded vectors bearing a uniquely located thymine-thymine cis-syn cyclobutane dimer were constructed as described previously (1, 2). In this method, M13mp7L2 hybrid phage single-stranded DNA is linearized by restriction with EcoRI within a small duplex hairpin region and then recircularized by annealing with a 51-mer scaffold oligonucleotide. The 51-mer anneals to a 20-nucleotide sequence at each end of the vector, leaving a central 11-nucleotide gap between the vector ends into which an 11-mer containing a uniquely positioned T-T dimer can be ligated with >95% efficiency. Similar controls are constructed with dimer-free 11-mer. The dimer-containing 11-mer is prepared as described previously (1) and is ∼99.5% pure. Following ligation, the scaffold is removed by heat denaturation in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of a 51-mer with complementary sequence to the scaffold, to prevent reannealing to the vector.

Five hundred microliters of competent cells of each strain, either SOS induced by exposure to 4 J of 254-nm UV per m2 or uninduced, were transfected with 5 ng of control or dimer-containing construct, and the number of resulting plaques was recorded. Estimates of the frequency of TR, a necessary condition for transfection, were obtained by normalizing the number of plaques from lesion-containing constructs to that of the controls. The types and frequencies of nucleotide insertion opposite the T-T lesion site were determined by hybridization and sequence analysis. This analysis also detected the low frequency of plaques resulting from nonbypass events, arising from transfection with constructs lacking the 11-mer sequence, from those in which the scaffold had not been removed, or from transfection with a variety of other aberrant constructions. TR frequencies were calculated only from plaque counts resulting from true TR.

Northern analysis.

To determine the extent to which LexA-regulated genes are expressed in our E. coli K-12 nucleotide excision repair-deficient, polymerase-mutant strains, we assayed the expression of the ysdAB operon by Northern analysis. To do so, E. coli strains RW82 (ΔumuDC), DV05 (ΔumuDC mutD5), DV32 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC mutD5), DV36 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔumuDC mutD5), and DV38 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC) were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani media. Each overnight culture was diluted 1:100 in fresh Luria-Bertani and grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5. At this time, the culture was split into two, and one part was irradiated with 4 J of UV per m2. Total RNA was extracted from both the unirradiated and the irradiated cells by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Approximately 30 μg of RNA was subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing agarose gel containing 1.2% formaldehyde, and the RNA was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane using the TurboBlotter system (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The blot was prehybridized for 2 h at 42°C with EasyDIG (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) and hybridized for 16 h with the 5′-digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled oligonucleotide, AR#264 (5′-ACGTACCTT TCCGCTGCCTGTTGCC-3′). This oligonucleotide anneals to a region of the ysdAB operon, which we have previously shown to be tightly regulated by LexA (5). The membrane was subsequently washed twice with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 min at room temperature and twice at 55°C with 0.5× SSC containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Hybridized products were visualized following the manufacturer's recommended conditions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

RESULTS

Which DNA polymerase is responsible for dimer bypass in the absence of Pol V?

Pol V plays a pivotal role in the bypass of a variety of DNA lesions. In its absence, there is virtually no bypass (31, 36). Surprisingly, our previous studies indicated that efficient bypass of a single cis-syn dimer occurs in ΔumuDC strains if they also carry the proofreading-deficient mutD5 allele (36). The goal of this work was therefore to determine the identity of the DNA polymerase, or combination of polymerases, responsible for the efficient bypass in proofreading-deficient umu strains. To this end, an isogenic series of ΔumuDC mutD5 strains carrying deletions of genes encoding Pol I, Pol II, and Pol IV, either singly or in all possible combinations, were transfected with single-stranded, M13-based vectors carrying a single uniquely located T-T dimer or with exactly comparable dimer-free control vectors. The frequency of TR past the dimer, a necessary prerequisite for plaque formation, was estimated by normalizing the number of plaques obtained with the dimer-containing construct to the number obtained with an equal amount of lesion-free control vector.

The basic finding to be explained can be seen in the comparison of TR frequencies observed in UV-irradiated cells from strains TK603 (umuDC+ dnaQ+), DV12 (umuDC+ mutD5), RW82 (ΔumuDC dnaQ+), and DV05 (ΔumuDC mutD5) (Table 2). High dimer bypass frequencies (44.1 and 51.9%) are seen in strains carrying the wild-type umuDC+ operon, whether proofreading proficient (dnaQ+) or proofreading deficient (mutD5). Deletion of the umuDC operon in the proofreading-proficient background almost abolishes the capacity for dimer bypass (2.4%), but half or more (25.5%) of the umuDC+ dimer bypass frequency is found when the same deletion is introduced into a proofreading-deficient background. In addition to the high UV-induced TR frequency seen in DV05 (ΔumuDC mutD5) cells, there was also significant (17.7%) TR in the absence of UV irradiation. Interestingly, a substantial fraction of TR (irrespective of whether the strain was irradiated or not) is absent in an isogenic ΔumuDC mutD5 lexA3(Ind−) derivative (DV13), suggesting that most of the TR in the ΔumuDC mutD5 background is due to a LexA-regulated polymerase.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of replication past a T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer in unirradiated and UV-irradiated cells

| Strain | Relevant genotype | % TR (mean ± SD) past a T-T cis-syn dimer in:

|

No. of expts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unirradiated cells | UV-irradiated cells | |||

| TK603 | umuDC+dnaQ+ | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 44.1 ± 3.1 | 3 |

| RW82 | ΔumuDC dnaQ+ | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 2.4 ± 0.2a | 15 |

| DV12 | umuDC+mutD5 | 5.5 ± 0.6a | 51.9 ± 3.8a | 4 |

| DV05 | ΔumuDC mutD5 | 17.7 ± 3.4a | 25.5 ± 2.8a | 7 |

| DV13 | ΔumuDC mutD5 lexA3(Ind−) | 4.6 ± 0.3a | 10.9 ± 0.6a | 5 |

| DV34 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA | 26.5 ± 4.2 | 26.0 ± 2.9 | 3 |

| DV10 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolB | 14.6 ± 2.6a | 34.2 ± 5.4a | 5 |

| DV42 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔdinB | 27.6 ± 4.6 | 22.7 ± 2.6 | 6 |

| DV36 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA ΔpolB | 49.8 ± 5.7 | 52.0 ± 6.9 | 6 |

| DV40 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA ΔdinB | 28.9 ± 7.5 | 30.0 ± 5.2 | 3 |

| DV30 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolB ΔdinB | 23.6 ± 1.6 | 24.3 ± 7.5 | 2 |

| DV32 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB | 44.2 ± 7.6 | 39.1 ± 2.8 | 2 |

| DV38 | ΔumuDC dnaQ+ ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 3 |

Data from reference 36.

Although Pol II and Pol IV might seem to be likely candidates to account for the high levels of TR in DV05, both because of their known function in TR (22) and repression by LexA (16), neither in fact appears to be responsible for this bypass. Deletion of dinB and polB, either singly or together, does not appreciably reduce TR past the dimer in the ΔumuDC mutD5 background (Table 2, DV10, DV42, DV30). Similarly, the bypass is not dependent on Pol I, either alone or in combination with the other enzymes (Table 2, DV34, DV36, DV40, DV32). Indeed, bypass frequencies are appreciably increased, rather than decreased, in DV32 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC mutD5) and DV36 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔumuDC mutD5), and to a lesser extent the same is true in DV40 (ΔpolA ΔdinB ΔumuDC mutD5). Thus, none of the nonessential DNA polymerases, alone or in combination, are responsible for the observed bypass. The high dimer bypass frequency seen in the absence of the dispensable enzymes is, however, completely dependent on the absence of proofreading (Table 2, compare DV32 and DV38), since it is abolished in DV38 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC dnaQ+). This surprisingly suggests that bypass is carried out by Pol III holoenzyme, although only when 5′-3′ exonucleolytic proofreading is greatly reduced by the dnaQ mutation mutD5.

Why do ΔumuDC mutD5 cells promote efficient TR in the absence of UV irradiation

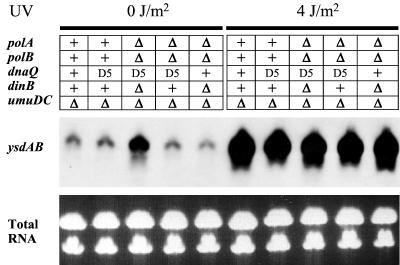

All of the lexA+ ΔumuDC mutD5 derivatives, no matter which of the DNA polymerase genes had been deleted, exhibited significant levels of TR in the absence of exogenous UV irradiation, although the extent of TR varied appreciably (Table 2). Most of the TR is apparently LexA dependent, since it decreased from 17.7% ± 3.4% to 4.6% ± 0.3% (mean ± standard deviation) in the DV05 derivative, DV13, which carries the noninducible allele, lexA3(Ind−). Although neither polB nor dinB appears responsible for the TR, over 40 other genes are known to be negatively regulated at the transcriptional level by LexA protein (4, 5) and one or more of these gene products might contribute to the efficient Pol III mutD5-dependent TR in the ΔumuDC strains. Indeed, based upon the fact that higher-than-expected levels of the LexA-regulated Umu proteins were observed when a low-copy-number plasmid expressing umu genes was introduced into DV05 (36), we speculated that the LexA regulon may be partially derepressed in the ΔumuDC mutD5 background. To further investigate the induction status of the mutD5 strains in a more direct manner, we assayed the expression of the ysdAB operon by Northern analysis. The ysdAB operon is known to be tightly regulated by LexA (5), and analysis of its expression therefore provides a sensitive test of LexA repression and/or derepression. As shown in Fig. 2, high ysdAB expression was found in all irradiated strains examined, but curiously, among the unirradiated strains increased expression of the ysdAB operon was observed only in the ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC mutD5 strain, DV32. Strangely, no increase was found in the ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔumuDC mutD5 strain DV36, which exhibited dimer bypass frequencies in the absence of UV irradiation that were at least as high as those in DV32, and possibly higher. Given the large differences in levels of ysdAB messenger observed in the various unirradiated and irradiated cells and the relatively small differences in TR in the absence or presence of UV irradiation (Table 2), we must conclude that Pol III mutD5-dependent TR is largely insensitive to the induction status of the LexA regulon. Thus, at present we cannot explain why the noninducible lexA3(Ind−) allele should have such a dramatic effect in reducing TR in the unirradiated cells, since the LexA-regulon in DV05 appears to be already in a repressed state in the absence of DNA damage.

FIG. 2.

Expression of the LexA-controlled ysdAB operon in unirradiated and UV-irradiated polymerase-deficient strains. The upper panel gives the polymerase genotype of each strain background. +, wild-type allele; Δ, deletion/substitution allele; D5, missense dnaQ allele mutD5. The five strains used in this experiment were RW82 (ΔumuDC), DV05 (ΔumuDC mutD5), DV32 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC mutD5), DV36 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔumuDC mutD5), and DV38 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC). The expression of the ysdAB operon was assayed by Northern analysis using the 5′-DIG-labeled oligonucleotide, AR#264 (middle panel). The lower panel depicts the total RNA in the ethidium bromide-stained gel prior to transfer and serves to ensure that equal amounts of RNA were loaded in each track. All strains induced ysdAB strongly after UV irradiation, but DV32 (ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC mutD5) also appeared to express moderate levels in the absence of an inducing treatment.

Mutation spectra and error rates of dimer bypass by Pol V and proofreading-deficient Pol III.

The existence of dimer bypass activity in the absence of Pol V provides an unusual opportunity to examine, in vivo, the types and frequencies of misinsertions made by two substantially different polymerases during lesion bypass on an identical cis-syn cyclobutane T-T dimer substrate. Although both enzymes make errors exclusively at the site of the 3′ thymine, their mutation spectra are significantly different (Table 3). In the UV-irradiated Pol V-proficient strains, TK603 and DV12, the mutations observed are predominantly T→A, with a few T→C (combined data show 45 T→A and 4 T→C). This result is in keeping with a large body of data from previous investigations (19, 23, 31). In strains lacking Pol V, however, no T→A mutations were observed (combined data, 0 T→A and 466 T→C). Both types of mutation were also seen in unirradiated TK603 and DV12 cells (combined data, 2 T→A and 5 T→C), but no T→A mutations were found in unirradiated cells of strains lacking Pol V (combined data, 0 T→A and 50 T→C). Clearly, the misinsertion of T opposite the 3′ T that is responsible for the T→A mutation is made very rarely by Pol III, although it is made commonly by Pol V. In addition to the difference in spectra, UV-irradiated strains possessing Pol V tend to exhibit higher error rates than do strains in which the enzyme is absent, though there is some variability. Overall, Pol III appears to be about twofold more accurate than Pol V (combined data show error rates of 5.4% for Pol V and 2.5% for Pol III). Although the error rate in the Pol V-deficient strain, DV05, appears similar to those in the strains expressing this enzyme, statistical analysis provides no support for a difference between the results for this and the other ΔumuDC strains.

TABLE 3.

Sequence at T-T target site in replicated vectors

| Strain | Relevant genotype | UV light fluence to cells (J/m2) | No. of indicated sequences at T-T dimer site

|

Error rate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-T | T-C | T-A | ΔT | Other | ||||

| TK603 | umuDC+dnaQ+ | 0 | 204 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 540 | 3 | 27 | 1 | 0 | 5.4 | ||

| RW82 | ΔumuDC dnaQ+ | 0 | 154 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 4 | 355 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| DV12 | umuDC+mutD5 | 0 | 183 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 |

| 4 | 355 | 1 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 5.3 | ||

| DV05 | ΔumuDC mutD5 | 0 | 67 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5.6 |

| 4 | 90 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 | ||

| DV13 | ΔumuDC mutD5 lexA3 | 0 | 421 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 |

| 4 | 661 | 21 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.2 | ||

| DV34 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA | 0 | 283 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.1 |

| 4 | 293 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.7 | ||

| DV10 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolB | 0 | 391 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.5 |

| 4 | 441 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | ||

| DV42 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔdinB | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| DV36 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA ΔpolB | 0 | 284 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 |

| 4 | 289 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | ||

| DV40 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA ΔdinB | 0 | 119 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 103 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | ||

| DV30 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolB ΔdinB | 0 | 172 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 |

| 4 | 169 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.9 | ||

| DV32 | ΔumuDC mutD5 ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB | 0 | 189 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 185 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.6 | ||

| DV38 | ΔumuDC dnaQ+ ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

DISCUSSION

There is abundant evidence that TR past UV damage in E. coli requires the UmuD′2C proteins (7, 10, 11, 29, 30), now known to constitute Pol V (26, 32). Experiments with single-stranded vectors carrying a site-specific cis-syn cyclobutane T-T dimer demonstrate this with particular clarity (31, 36); almost no TR past this photoproduct occurs in strains with a deletion of umuDC. Nevertheless, we previously observed that efficient TR past a T-T dimer took place in ΔumuDC strains if the proofreading function of Pol III holoenzyme was inactivated by the dnaQ mutation mutD5 (36). We have examined two alternative hypotheses to explain this observation: first, that in the absence of Pol V, Pol III outcompetes other polymerases in binding to the blocked primer terminus, effectively denying access to other polymerases, but is itself incapable of performing TR. The inactivation of proofreading by the mutD5 mutation might then reduce the binding affinity of Pol III, restoring access to the other enzymes; and second, that the TR is carried out by the proofreading-deficient Pol III itself.

Surprisingly, we find that the second hypothesis appears to be correct. Although Pol III holoenzyme is generally thought to be concerned exclusively with the replication of undamaged templates, we find that in the absence of the 3′-5′ exonucleolytic proofreading activity encoded by its ɛ subunit, it is capable of bypassing a cis-syn cyclobutane T-T dimer with an apparent efficiency, which, at least by the relatively crude measure of plaque formation, equals that of Pol V, the enzyme that normally performs dimer bypass. Although there may well be considerable latitude in the time needed to carry out TR and set up a successful transfection, which could mask differences between the two enzymes, the data still imply that the proportion of vectors completely replicated by each of them is similar. Deletion of the genes encoding Pol I, Pol II, or Pol IV, either singly or in all combinations, failed to abolish the TR seen in the UV-irradiated ΔumuDC mutD5 strain, DV05 (Table 1). Indeed, the level of TR in these strains, rather than being decreased, was in some cases increased, particularly when Pol I and Pol II were jointly absent, perhaps because of decreased competition for primer termini. Pol III is implicated in the TR because restoration of Pol III proofreading competence in the ΔpolA ΔpolB ΔdinB ΔumuDC strain abolished its TR capability. The possibility that the absence of proofreading in some way facilitates the activity of a sixth, as yet to be identified DNA polymerase cannot be entirely eliminated but seems unlikely in view of the existence of complete information for the E. coli genome (3). Nevertheless, such information did not reveal the existence of Pol IV or Pol V, so the possibility of an additional enzyme cannot be completely discounted.

The finding that Pol III can replicate past a cyclobutane dimer if proofreading is inhibited supports a model proposed nearly 25 years ago (37) to explain inhibition of polymerase progression by UV photoproducts in the DNA template. However, such an explanation does not apply to all photoproducts; very little bypass of a T-T pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidinone photoadduct was observed in either UV-irradiated or unirradiated DV05 cells (−UV, 0.9%; +UV, 1.0%; averages of two experiments). Replication past the dimer in the absence of proofreading may well be facilitated by the ability of each thymine to form base pairs with adenine (15, 33), and it is possible that other lesions with full base pair-forming capacity that also can be bypassed by a proofreading-deficient Pol III enzyme may exist (for an example, see reference 8). Even so, it is not obvious why T-T dimer bypass depends on the absence of proofreading, since adenine is in fact inserted in >95% of bypass events, precluding the need for editing. Perhaps, as Radman and his coworkers suggested (37), primer extension is inhibited by repeated proofreading of the correct nucleotide, an event encouraged by the slightly distorted structure of the template. Nevertheless, as the observations with the T-T (6-4) photoadduct show, the possible stimulation of inappropriate proofreading cannot alone explain inhibition of primer extension by all lesions. In these other cases some aspect of the interaction between the polymerase and the highly distorted structure itself, independent of proofreading, must be the major factor.

Although Pol III mutD5 and Pol V, both proofreading-deficient enzymes, are capable of TR in a similar fraction of vector molecules, the error rates of bypass are different and produce different mutation spectra (Table 3). Proofreading-deficient Pol III appears overall to be a more accurate enzyme, achieved in large part by a stringent rejection of the T · T mispair that gives rise to the 3′ T→A mutation predominantly generated during dimer bypass by Pol V. Greater stringency against the T · T mispair is, however, accompanied by a reduced stringency against the T · G base pair that produces the 3′ T→C mutation, because the absolute frequency of these events is higher with Pol III mutD5 (∼2.5%) than with Pol V (∼0.5%). This result may reflect the tight control imposed by Pol III on potential base pair dimensions, since the T · T mispair is grossly abnormal, whereas the T · G mispair is much more normal in this respect. Although at first sight it might seem that the greater laxity of Pol V in base selection is required for dimer bypass, this conclusion may well be wrong, since the distantly related human Pol ι also preferentially misincorporates T opposite the 3′ T of the cis-syn T-T dimer yet bypasses the lesion inefficiently (34). Conversely, MucA′B, a more closely related member of the Y family of DNA polymerases (24), bypasses the cis-syn T-T dimer more efficiently than Pol V, yet resembles Pol III in its misincorporation specificity; like Pol III, it has a twofold-lower error rate than Pol V and generates more than sevenfold more T→C than T→A mutations (23). Thus, it seems more likely that the efficiency of lesion bypass and the differences one observes in mutational spectra between various members of the Y family of DNA polymerases arise from just a few amino acid substitutions at key locations within the active site of each enzyme. The recently described crystal structures of three related Y-family DNA polymerases (20, 28, 35, 40) should hopefully provide insights into both the efficiency and the accuracy of lesion bypass promoted by these fascinating polymerases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH Intramural Research Program and by grant GM32885 to C.W.L. from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Roel Schaaper, Patricia Foster, Catherine Joyce, Eiji Ohashi, Haruo Ohmori, and Myron Goodman for kindly providing various E. coli strains that allowed us to generate the multiple polymerase-deficient strains used in our present studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee, S. K., R. B. Christensen, C. W. Lawrence, and J. E. LeClerc. 1988. Frequency and spectrum of mutations produced by a single cis-syn thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimer in a single-stranded vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:8141-8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee, S. K., A. Borden, R. B. Christensen, J. E. LeClerc, and C. W. Lawrence. 1990. SOS-dependent replication past a single trans-syn T-T dimer gives a different mutation spectrum and increased error rate compared with replication past this lesion in uninduced cells. J. Bacteriol. 172:2105-2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcelle, J., A. Khodursky, B. Peter, P. O. Brown, and P. C. Hanawalt. 2001. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158:41-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández de Henestrosa, A. R., T. Ogi, S. Aoyagi, D. Chafin, J. J. Hayes, H. Ohmori, and R. Woodgate. 2000. Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA-regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1560-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank, E. G., M. Gonzalez, D. G. Ennis, A. S. Levine, and R. Woodgate. 1996. In vivo stability of the Umu mutagenesis proteins: a major role for RecA. J. Bacteriol. 178:3550-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedberg, E. C., G. C. Walker, and W. Siede. 1995. DNA repair and mutagenesis. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Fuchs, R. P. P., and R. L. Napolitano. 1998. Inactivation of DNA proofreading obviates the need for SOS induction in frameshift mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13114-13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatignol, A., H. Durand, and G. Tiraby. 1988. Bleomycin resistance conferred by a drug-binding protein. FEBS Lett. 230:171-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez, M., and R. Woodgate. 2001. The “tale” of UmuD and its role in SOS mutagenesis. BioEssays 24:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman, M. F., and R. Woodgate. 2000. The biochemical basis and in vivo regulation of SOS-induced mutagenesis promoted by Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V (UmuD′2C). Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 65:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho, C., O. I. Kulaeva, A. S. Levine, and R. Woodgate. 1993. A rapid method for cloning mutagenic DNA repair genes: isolation of umu-complementing genes from multidrug resistance plasmids R391, R446b, and R471a. J. Bacteriol. 175:5411-5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce, C. M., and N. D. F. Grindley. 1984. Method for determining whether a gene of Escherichia coli is essential: application to the polA gene. J. Bacteriol. 158:636-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato, T., and Y. Shinoura. 1977. Isolation and characterization of mutants of Escherichia coli deficient in induction of mutations by ultraviolet light. Mol. Gen. Genet. 156:121-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemmink, J., R. Boelens, T. Koning, G. A. van der Marel, J. H. van Boom, and R. Kaptein. 1987. NMR study of the exchangeable protons of the duplex d(GCGTTGCG) · d(CGCAACGC) containing a thymine photodimer. Nucleic Acids Res 15:4645-4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenyon, C. J., and G. C. Walker. 1980. DNA-damaging agents stimulate gene expression at specific loci in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:2819-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, S. R., K. Matsui, M. Yamada, P. Gruz, and T. Nohmi. 2001. Roles of chromosomal and episomal dinB genes encoding DNA pol IV in targeted and untargeted mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornberg, A., and T. A. Baker. 1992. DNA replication. W. H. Freeman, New York, N.Y.

- 19.Lawrence, C. W., S. K. Banerjee, A. Borden, and J. E. LeClerc. 1990. T-T cyclobutane dimers are misinstructive, rather than non-instructive, mutagenic lesions. Mol. Gen. Genet. 222:166-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ling, H., F. Boudsocq, R. Woodgate, and W. Yang. 2001. Crystal structure of a Y-family DNA polymerase in action: a mechanism for error-prone and lesion-bypass replication. Cell 107:91-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy, K. C. 1998. Use of bacteriophage λ recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:2063-2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Napolitano, R., R. Janel-Bintz, J. Wagner, and R. P. P. Fuchs. 2000. All three SOS-inducible DNA polymerases (Pol II, Pol IV and Pol V) are involved in induced mutagenesis. EMBO J. 19:6259-6265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Grady, P. I., A. Borden, D. Vandewiele, A. Ozgenc, R. Woodgate, and C. W. Lawrence. 2000. Intrinsic polymerase activities of UmuD′2C and MucA′2B are responsible for their different mutagenic properties during bypass of a T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer. J. Bacteriol. 182:2285-2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohmori, H., E. C. Friedberg, R. P. P. Fuchs, M. F. Goodman, F. Hanaoka, D. Hinkle, T. A. Kunkel, C. W. Lawrence, Z. Livneh, T. Nohmi, L. Prakash, S. Prakash, T. Todo, G. C. Walker, Z. Wang, and R. Woodgate. 2001. The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell 8:7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rangarajan, S., R. Woodgate, and M. F. Goodman. 1999. A phenotype for enigmatic DNA polymerase II: a pivotal role for pol II in replication restart in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9224-9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuven, N. B., G. Arad, A. Maor-Shoshani, and Z. Livneh. 1999. The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD′, RecA, and SSB and is specialized for translesion replication. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31763-31766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaaper, R. M., and R. Cornacchio. 1992. An Escherichia coli dnaE mutation with suppressor activity toward mutator mutD5. J. Bacteriol. 174:1974-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvian, L. F., E. A. Toth, P. Pham, M. F. Goodman, and T. Ellenberger. 2001. Crystal structure of a DinB family error-prone DNA polymerase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:984-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutton, M. D., and G. C. Walker. 2001. Managing DNA polymerases: coordinating DNA replication, DNA repair, and DNA recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8342-8349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton, M. D., B. T. Smith, V. G. Godoy, and G. C. Walker. 2001. The SOS response: recent insights into umuDC-dependent mutagenesis and DNA damage tolerance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34:479-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szekeres, E. S., Jr., R. Woodgate, and C. W. Lawrence. 1996. Substitution of mucAB or rumAB for umuDC alters the relative frequencies of the two classes of mutations induced by a site-specific T-T cyclobutane dimer and the efficiency of translesion DNA synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:2559-2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang, M., X. Shen, E. G. Frank, M. O'Donnell, R. Woodgate, and M. F. Goodman. 1999. UmuD′2C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8919-8924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor, J. S., D. S. Garrett, I. R. Brockie, D. L. Svoboda, and J. Telser. 1990. 1H NMR assignment and melting temperature study of cis-syn and trans-syn dimer containing duplexes of d(CGTATTATGC) · d(GCATAATACG). Biochemistry 29:8858-8866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tissier, A., E. G. Frank, J. P. McDonald, S. Iwai, F. Hanaoka, and R. Woodgate. 2000. Misinsertion and bypass of thymine-thymine dimers by human DNA polymerase ι. EMBO J. 19:5259-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trincao, J., R. E. Johnson, C. R. Escalante, S. Prakash, L. Prakash, and A. K. Aggarwal. 2001. Structure of the catalytic core of S. cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. Implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 8:417-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandewiele, D., A. Borden, P. I. O'Grady, R. Woodgate, and C. W. Lawrence. 1998. Efficient translesion replication in the absence of Escherichia coli Umu proteins and 3′-5′ exonuclease proofreading function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15519-15524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villani, G., S. Boiteux, and M. Radman. 1978. Mechanism of ultraviolet-induced mutagenesis: extent and fidelity of in vitro DNA synthesis on irradiated templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:3037-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner, J., P. Gruz, K. Su-Ryang, M. Umada, K. Matsui, R. P. P. Fuchs, and T. Nohmi. 1999. The dinB gene encodes a novel E. coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Mol. Cell 4:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodgate, R. 1992. Construction of a umuDC operon substitution mutation in Escherichia coli. Mutat. Res. 281:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou, B., J. D. Pata, and T. A. Steitz. 2001. Crystal structure of a DinB lesion bypass DNA polymerase catalytic fragment reveals a classic polymerase catalytic domain. Mol. Cell 8:427-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]